Manchuria under Ming rule

Manchuria under Ming rule refers to the domination of the Ming dynasty over Manchuria, including today's Northeast China and Outer Manchuria. The Ming rule of Manchuria began with its conquest of Manchuria in the late 1380s after the fall of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty, and reached its peak in the early 15th century with the establishment of the Nurgan Regional Military Commission, but the Ming power waned considerably in Manchuria after that. Starting in the 1580s, a Jianzhou Jurchen chieftain named Nurhaci (1558–1626), began to take control of most of Manchuria over the next several decades, and the Qing dynasty established by his son would eventually conquer the Ming and take control of China proper.

| Manchuria under Ming rule | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory of the Ming dynasty | |||||||||

| 1388–1616 | |||||||||

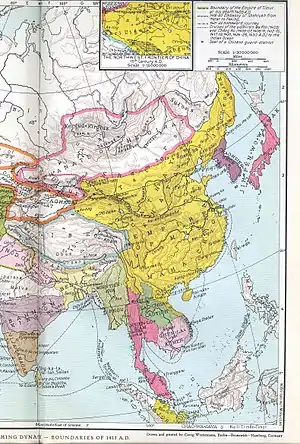

Ming China during the reign of the Yongle Emperor | |||||||||

| • Type | Ming hierarchy | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1387 | |||||||||

• Established | 1388 | ||||||||

• Establishment of the Nurgan Regional Military Commission | 1409 | ||||||||

• Abolishment of the Nurgan Regional Military Commission | 1435 | ||||||||

• Beginning of actual control of most of Manchuria by Nurhaci | 1580s | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1616 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Manchuria |

|

History

The Mongol Empire conquered all Manchuria (modern Northeast China and Outer Manchuria) in the 13th century and it was put under the rule of the Yuan dynasty established by Kublai Khan. After the overthrow of the Yuan dynasty by the Han Chinese Ming dynasty in 1368, Manchuria was still under the rule of the Yuan remnants, known in historiography as the Northern Yuan dynasty. Naghachu, a former Yuan official and a Uriankhai general of the Northern Yuan dynasty, won hegemony over the Mongol tribes in Manchuria (Liaoyang province of the former Yuan dynasty). As he grew strong in the northeast, the Ming decided to defeat him instead of waiting for the Mongols to attack. In 1387 the Ming sent a military campaign to attack Naghachu,[1] which concluded with the surrender of Naghachu and Ming conquest of Manchuria.

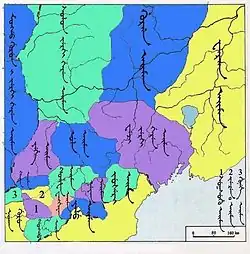

The early Ming court did not impose as much control on the Jurchens as the Yuan dynasty did; it did not tax them, and did not set up postal stations in Liaodong and northern Manchuria (as the Yuan dynasty had), which would have promoted control. Despite this, the Ming court set up guards (衛, wei) in Lingdong under the Hongwu Emperor and in northern Manchuria later under the Yongle Emperor. However, the Jurchen leaders continued to collect the taxes and raise armies for themselves. Jurchen society did not become sinicized; the guards served to reaffirm traditional Chinese foreign relations.[2]

By the end of the Hongwu reign, the essentials of a policy toward the Jurchens had taken shape. Most of the inhabitants of Manchuria, except for the wild Jurchens, were at peace with China. Yet a suitable relationship between Ming China and their neighbors to the northeast had not been established. The guard system had scarcely reached into northern Manchuria, and the regulations for tribute and commerce were still relatively unformed. The Yongle Emperor once again was responsible for devising the framework for Ming-Jurchen relations. He sought peace with the Jurchens and tried to prevent them from allying with the Mongols or the Koreans to pose threats to the Chinese borderlands. One way of winning over the Jurchens was to initiate a regular system of tribute and trade, a boon to these northeastern neighbors, as well as to the Ming, which needed and coveted certain Jurchen products. Finally, the emperor distinguished between Liaodong and the other Jurchen areas farther to the north. Liaodong was to be part of the normal administrative system of the Ming, with the creation of a Regional Military Commission and a commensurate set of military and fiscal obligations which were similar to those imposed upon and generally fulfilled by provinces in China proper. And in northern Manchuria, the Yongle Emperor had created a series of guards and had superseded Korean influence among the Jurchens. He had achieved peace in the Jurchen lands adjacent to the Tumen, Amur, Songhua, and Ussuri rivers, and the Chinese government had developed expertise about the different Jurchen groups and leaders. Chinese cultural and religious influence such as Chinese New Year, the "Chinese god", Chinese motifs like the dragon, spirals, scrolls, and material goods like agriculture, husbandry, heating, iron cooking pots, silk, and cotton spread among the Amur natives like the Udeghes, Ulchis, and Nanais.[3]

However, the creation of a guard did not necessarily imply political control. In 1409, the Ming dynasty under Yongle Emperor established the Nurgan Regional Military Commission on the banks of the Amur River, and Yishiha, a eunuch of Haixi Jurchen derivation, was ordered to lead an expedition to the mouth of the Amur to pacify the Wild Jurchens. The reception he was accorded by Jurchen chiefs was cordial, and he responded by providing them with gifts. They, in turn, agreed to the Ming creation of the Nurgan Regional Military Commission and to the dispatch of a tribute mission to accompany Yishiha back to the court. In 1413, the emperor again sent Yishiha to Nurgan to meet with the Jurchen chiefs and to build the Yongning temple in an attempt to promote Buddhism among the least sedentarized of the Jurchens. Nurgan was the site of Yongning Temple (永寕寺), a Buddhist temple dedicated to Guanyin, that was founded by Yishiha (Išiqa) in 1413.[4] There is some evidence that he reached the Sakhalin island[5] during one of his expeditions to the lower Amur, and granted Ming titles to a local chieftain. His efforts were well-received because he was well-informed about Jurchen custom and attitudes. Tribute and trade from Nurgan began to flow into China; the Jurchen chiefs accepted the bestowal of titles by the Ming; Buddhism was promoted among the native peoples, and commerce and communication were facilitated through the postal stations established in Nurgan. Yet, the Ming court did not dominate the political fortunes of the Wild Jurchens. It simply maintained a presence in the far northeast of Manchuria. After Yongle Emperor's death, it became increasingly difficult to do so.[6] According to the Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty, the Ming established 384 guards and 24 battalions in Manchuria, but these were probably only nominal offices.[7]

Some sources report a Chinese fort existed at Aigun for about 20 years during the Yongle era on the left (northwestern) shore of the Amur downstream from the mouth of the Zeya River. This Ming Dynasty Aigun was located on the opposite bank to the later Aigun that was relocated during the Qing Dynasty.[8] Yishiha's last fleet included 50 big ships with 2,000 soldiers, and they actually brought the newly inaugurated chief (who had been living in Beijing) to Tyr.[9]

The Nurgan Regional Military Commission was abolished in 1435, 11 years after the death of the Yongle Emperor, and although the guards continued to exist in Manchuria, the Ming court ceased to have substantial administrative activities there because the heads of local ethnic groups acted as the local officials, and many of the Jurchen villages and guards became semi-hereditary tribes or low-rank duchy. After that, these guards and the affairs of Manchuria were managed by the Liaodong Military Commission of Shandong Province. Although the Ming government and the Jurchen tribe still engaged in sovereign activities such as paying tribute, the conflicts continued to increase, and the Ming government carried out many encirclement and suppression on the rebellious Jurchen tribe in Manchuria. The most important battles were the two "plowing" operations of Manchuria by Chenghua Emperor in 1467 and 1479, and the suppression of Jurchen Atai rebels in 1583. Li Chengliang, the commander-in-chief of Liaodong of the Ming Dynasty, mistakenly killed Nurhachi's father and grandfather in this battle with Atai. By the late Ming period, Ming political presence in Manchuria had waned considerably, although it continued to give titles to Jurchen chiefs. Ironically, however, it was in fact the peoples in this region that caused the downfall of the Ming dynasty.[10] [11] Starting in the 1580s, Nurhaci (1558–1626), a Jianzhou Jurchen chieftain who was nominally a Ming vassal, started to take actual control of most of Manchuria over the next several decades. In 1616, he declared himself the "Bright Khan" of the Later Jin state. Two years later he announced the "Seven Grievances" and openly renounced the sovereignty of Ming overlordship and started to fight against the Ming. In 1636, the ethnic name "Manchu" was formally adopted and the dynastic name Later Jin was changed to Great Qing, with its original capital situated at Mukden (Shenyang) slightly north of the Willow Palisade that defined the border of the Liaodong region ruled by Ming. In 1644, after the Chinese rebel Li Zicheng had overthrown the Ming dynasty, loyalist Chinese general Wu Sangui invited Qing forces to drive Li out of Beijing. Qing ruled north China for 40 years until 1683 when they won a civil war against their former loyal vassals in south China, and thereby gained rule over all of China Proper. This is the realm that Wei Yuan 魏源 in 1840 defined as: "The lands of the 17 Han provinces (received from Ming) and the Three Eastern Provinces (the Manchu homeland) are the Centralized State 中國. To the west of the Centralized State is the Muslim region, to the south are Wei and Zang (Nearer and Farther Tibet tribals, also received from Ming), to the east is Korea, to the north is Russia."[12]

The change of the name from Jurchen to Manchu was made to hide the fact that the ancestors of the Manchus, the Jianzhou Jurchens, were ruled by the Chinese.[13][14][15] The Qing dynasty carefully hid the 2 original editions of the books "Qing Taizu Wu Huangdi Shilu" and "Manzhou Shilu Tu" (Taizu Shilu Tu) in the Qing palace, forbidden from public view because they showed that the Manchu Aisin Gioro family had been ruled by the Ming dynasty.[16][17] In the Ming period, the Koreans of Joseon referred to the Jurchen inhabited lands north of the Korean peninsula, above the rivers Yalu and Tumen, as part of Ming China, and called the Jurchen lands the "superior country" (sangguk), the name by which they called Ming China.[18] The Qing deliberately concealed the Manchus' former subservience to the Ming by excluding from the History of the Ming references and information that showed this former relationship. Because of this, History of Ming did not use the Veritable Records of Ming as a source for content on Jurchens during the period when they were ruled by Ming.[19]

See also

References

- Harmony and War: Confucian Culture and Chinese Power Politics, by Yuan-kang Wang

- The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, Part 2, by Denis C. Twitchett, Frederick W. Mote, p260

- Forsyth (1994), p. 214.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2002). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 58, 185. ISBN 978-0-520-23424-6.

- Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry (2002). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-295-98124-5.

- From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi, by Morris Rossabi, p193

- Perpetual happiness: the Ming emperor Yongle, by Shih-shan Henry Tsa, p159

- Du Halde, Jean-Baptiste (1735). Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique et physique de l'empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie chinoise. Volume IV. Paris: P.G. Lemercier. pp. 15–16. Numerous later editions are available as well, including one on Google Books. Du Halde refers to the Yongle-era fort, the predecessor of Aigun, as Aykom. There seem to be few, if any, mentions of this project in other available literature.

- Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry (1996). The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. SUNY Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 0-7914-2687-4.

- The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, Part 2, by Denis C. Twitchett, Frederick W. Mote, p260

- The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, Part 2, by Denis C. Twitchett, Frederick W. Mote, p258

- The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, Part 2, by Denis C. Twitchett, Frederick W. Mote, p260

- Hummel, Arthur W., ed. (2010). "Abahai". Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, 1644–1912 (2 vols) (reprint ed.). Global Oriental. p. 2. ISBN 978-9004218017. Via Dartmouth.edu

- Grossnick, Roy A. (1972). Early Manchu Recruitment of Chinese Scholar-officials. University of Wisconsin—Madison. p. 10.

- Till, Barry (2004). The Manchu era (1644–1912): arts of China's last imperial dynasty. Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. p. 5. ISBN 9780888852168.

- Hummel, Arthur W., ed. (2010). "Nurhaci". Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, 1644–1912 (2 vols) (reprint ed.). Global Oriental. p. 598. ISBN 978-9004218017. Via Dartmouth.edu

- The Augustan, Volumes 17–20. Augustan Society. 1975. p. 34.

- Kim, Sun Joo (2011). The Northern Region of Korea: History, Identity, and Culture. University of Washington Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0295802176.

- Smith, Richard J. (2015). The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 216. ISBN 978-1442221949.

.png.webp)