Harsimus

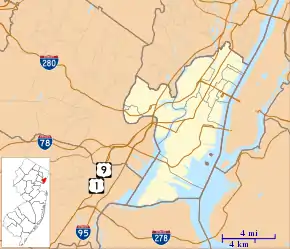

Harsimus (also known as Harsimus Cove) is a neighborhood within Downtown Jersey City, Hudson County, New Jersey, United States. The neighborhood stretches from the Harsimus Stem Embankment (the Sixth Street Embankment) on the north to Christopher Columbus Drive on the south between Coles Street and Grove Street[1] or more broadly, to Marin Boulevard. It borders the neighborhoods of Hamilton Park to the north, Van Vorst Park to the south, the Village to the west, and the Powerhouse Arts District to the east. Newark Avenue has traditionally been its main street.[2] The name is from the Lenape, used by the Hackensack Indians who inhabited the region and could be translated as Crow’s Marsh.[3] From many years, the neighborhood was part of the "Horseshoe", a political delineation created by its position between the converging rail lines and political gerrymandering.[4]

Early settlement

Harsimus is a derivative of a Lenape phrase, possibly meaning Crow's Marsh. Spellings include: Aharsimus,[5] Ahasimus,[6][7] Hasymes,[8] Haassemus, Hahassemes, Hasimus, Horseemes, Hasseme,[9] Horsimus [10] In current Lenape, ahas means "crow".[11]

In 1629, the Dutchman Michael Reyniersz Pauw obtained a patent for all the land in what would become Hudson County, naming it Pavonia. Unable to fulfill a patroon charter provision that he set up a plantation with fifty permanent settlers, the Dutch West India Company sold a part to his superintendent, who had built a homestead in 1634 and was the first of many Van Vorsts to play important roles in the development of the city. A family homestead built in 1647 was demolished in 1967.[12] Conflict with Native Americans compromised the settlement 1643, which continued to grow after the 1645 treaty ending Kieft's War. Again in 1655, the area was attacked in a conflict called the Peach Tree War. In 1660, it came under the jurisdiction of Bergen, New Netherland the main village of which was located at Bergen Square.[13]

_(14756945346).jpg.webp)

Once the area was ceded to the British after the surrender of Fort Amsterdam, New York claimed ownership to the high waterline along the west bank of the Hudson River and that any pier built there was under its jurisdiction, thus stifling development which would compete with the burgeoning New York City. Paulus Hook was the first to urbanize, and The City of Jersey was incorporated in various forms in 1820, 1829, and again in 1838.[14] John Coles, a merchant from New York, was among the first to expand into Harsimus.[15] The Supreme Court settled the matter of jurisdiction in the 1830s, creating a border mid-river. Harsimus grew with shipping along shoreline and residences farther inland.[16] The short-lived Van Vorst Township later merged with its neighbor. Much of the housing stock from the maritime era is still intact. Many of the streets in the gridiron laid at the time have been renamed over the years. Moving away from the river they were originally called Hudson, River, Kelso, and Barnum. Provost and others to the west have stayed the same.[17]

Rise of the railroad and Hague

Harsimus was transformed by the development of the railroad industry.[18] By 1870 much of the estuary flood zone was land-filled for the development of railyards, extending a quarter mile from Henderson Street. Three elevated right of ways were built: one from the Bergen Arches to the Erie Railroad Pavonia Terminal,[19][20] the Harsimus Stem Embankment[21][22] at 6th Street for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), and another for its Jersey City Branch along Railroad Avenue (now Columbus Drive) to Exchange Place. The embankments and elevated lines separated adjoining neighborhoods. A small slip was created and still is called Harsimus Cove. Huge stockyards dominated the waterfront between the train terminals.[23]

Harsimus' isolation was codified with gerrymandering, forming a horseshoe and creating a new nickname. The community consisted of Catholic immigrants, many of them Irish, who worked on the railroad. Infuxes of Ellis Island immigrants swelled the population. A vestige of the Slavic character of the area remains at the Ukrainian National Home. To diminish the Democratic power base, Republican power brokers redrew the voting district to consist solely of the Horseshoe so that they may protect other seats from Democratic threat. In the 1910s the Horseshoe power base produced the infamous Mayor Frank Hague who dominated the Hudson County political machine and influenced city, county, state, and federal politics for most of the first half of the 20th century. In 1941 a large fire struck the Horsehoe waterfront.[24]

Post industrial era

Harsimus Cove Historic District | |

Fountain and Park on Second and Grove Street. | |

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Grove, Bay & First Sts., Jersey Avenue, Second, & Coles Sts., Jersey City, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°43′24″N 74°2′41″W |

| Area | 60 acres (24 ha) |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Late 19th And 20th Greek Revival, Late Victorian, Beaux Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | 87002118[25] |

| NJRHP No. | 1509[26] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 9, 1987 |

| Designated NJRHP | October 15, 1987 |

In the late 1950s, container shipping in Port Newark supplanted railroad ports along waterfront, which by the 1970s were abandoned, leading to a decline in population and economic activity. Urban renewal projects brought slum clearance of tenements along Grove Street as well as the removal of the PRR elevated rail right of way. Middle, low income, and senior housing projects were developed. A section of Grove Street was renamed Manila Avenue in recognition of the city's resident Overseas Filipinos. Henderson Street became Marin Boulevard for the first governor of Puerto Rico Luis Muñoz Marín to reflect the influx of Puerto Rican and Filipino residents. Railroad Avenue is now Columbus Drive, acknowledging the still large Italian population.

The renewal did not affect the 19th century blocks which were not demolished. A historic preservation movement and real estate reinvestment led to Harsimus's designation as a Historic District in 1987.[27] Convenience to mass transit and relatively affordable rents attracted an artistic community, some of whom converted buildings to live/work spaces. Zoning in the form of "WALDO" (or Work and Live District Overlay) were unsuccessful in preserving and stimulating the creation of an arts district within the area where large warehouses still remained, and have given way the Powerhouse Arts District and the construction of residential highrises.

East of the neighborhood, the LeFrak Organization obtained title to most of the disused Erie-Lackawanna land and began the development of Newport, centered around the Port Authority Trans Hudson (PATH) Newport Station in the 1980s.[28] To the south, the PRR abattoir were also acquired.[29] Development plans did not include extending the 19th century urban grid to the waterfront, but the construction of large parking decks at the former and strip mall at the latter. The first segment of the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail opened in 2002, including the Harsimus Cove Station nearby the landmark Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Powerhouse.

Grove Pointe, a residential complex at 100 and 102 Christopher Columbus Drive, the "30-story tiered brick-and-stone structure with abundant glass" was designed by DeWitt Tishman Architects[30]and built by Kushner Real Estate Group.[31]

See also

- New Netherland

- Communipaw

- Harsimus Branch

- Horseshoe, Jersey City

- Jersey City and Harsimus Cemetery

- List of Registered Historic Places in Hudson County, New Jersey

- Historic Districts in Hudson County, New Jersey

- New Netherland settlements

- English Neighborhood

- Achter Col

- Vriessendael

- Van Vorst Township

- St. Mary High School (Jersey City, New Jersey)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harsimus. |

References

- "History - Harsimus Cove Association of Jersey City". www.harsimuscove.org.

- "Jersey City Shopping Districts". www.jerseycityonline.com.

- "Lenape talking dictionary". Archived from the original on 2016-05-19. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-05-23. Retrieved 2009-10-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Jersey City History - Old Bergen - Chapter VII". www.cityofjerseycity.org.

- "Swtext New Jersey Tribes 1d". www.hiddenhistory.com.

- "Delaware Indian Tribe Villages - Access Genealogy". 9 July 2011.

- "RootsWeb.com Home Page". archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2008-11-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-10-20. Retrieved 2010-04-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-19. Retrieved 2009-10-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Van Vorst House". Archived from the original on 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- "The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968", John P. Snyder, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 146–147.

-

- Hamilton Park History Archived 2010-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- "History - Harsimus Cove Association of Jersey City". www.harsimuscove.org.

- Hopkins, G.M. Combined Atlas of the State of New Jersey and the County of Hudson, 1873

- Short history of Harsimus Cove Archived 2009-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Jersey City Past and Present: Erie Railroad Terminal Archived 2012-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "New-Jersey" (PDF). The New York Times. August 8, 1873.

- "The Harsimus Stem Embankment". Archived from the original on 2009-09-27. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- "JC Landmarks: Harsimus Stem Embankmentl".

- "NY Times 1894" (PDF).

- "Jersey City - Historic Preservation Districts". www.cityofjerseycity.org.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places - Hudson County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection - Historic Preservation Office. July 7, 2009. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- "Neighborhood Map - Harsimus Cove Association of Jersey City". www.harsimuscove.org.

- "Shanghai on the Hudson".

- Depalma, Anthony (May 12, 1985). "A $700 Million Plan for Jersey City's Shore". The New York Times.

- "Rentals' New Lease on Life". New York Times. 16 December 2007.

- Hack, Charles (11 April 2013). "Spotlight 2013: Major development projects are in the works for Jersey City". Journal-News. Retrieved 20 June 2019.