History of French

French is a Romance language (meaning that it is descended primarily from Vulgar Latin) that evolved out of the Gallo-Romance.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| French language |

|---|

|

| History |

| Grammar |

| Orthography |

| Phonology |

|

The discussion of the history of a language is typically divided into "external history", describing the ethnic, political, social, technological, and other changes that affected the languages, and "internal history", describing the phonological and grammatical changes undergone by the language itself.

External history

Roman Gaul (Gallia)

Before the Roman conquest of what is now France by Julius Caesar (58–52 BC), much of present France was inhabited by Celtic-speaking people referred to by the Romans as Gauls and Belgae. Southern France was also home to a number of other remnant linguistic and ethnic groups including Iberians along the eastern part of the Pyrenees and western Mediterranean coast, remnant Ligures on the eastern Mediterranean coast and in the alpine areas, Greek colonials in places such as Marseille and Antibes,[1] and Vascones and Aquitani (Proto-Basques) in much of the southwest.[2][3] The Gaulish speaking population is held to have continued speaking Gaulish even as considerable Romanization of the local material culture occurred, with Gaulish and Latin coexisting for centuries under Roman rule, and the last attestation of Gaulish deemed credible[4] having been written in the second half of the 6th century about the destruction of a pagan shrine in Auvergne.[5]

The Celtic population of Gaul had spoken Gaulish, which is moderately well attested, with what appears to be wide dialectal variation including one distinctive variety, Lepontic. While the French language evolved from Vulgar Latin (i.e., a Latinised popular Italo-Celtic dialect called sermo vulgaris), it was nonetheless influenced by Gaulish.[6][7] Chief among these are sandhi phenomena (liaison, resyllabification, lenition), the loss of unstressed syllables, and the vowel system (e.g. raising /u/, /o/ → /y/, /u/, fronting stressed /a/ → /e/, /ɔ/ → /ø/ or /œ/).[8][9] Syntactic oddities attributable to Gaulish include the intensive prefix ro- ~ re- (cited in the Vienna glossary, 5th century)[10] (cf. luire "to glimmer" vs. reluire "to shine"; related to Irish ro- and Welsh rhy- "very"), emphatic structures, prepositional periphrastic phrases to render verbal aspect, the semantic development of oui "yes", aveugle "blind", and so on.

Some sound changes are attested. The sound changes /ps/ → /xs/ and /pt/ → /xt/ appears in a pottery inscription from la Graufesenque (1st century) where the word paraxsidi is written for paropsides.[11] Similarly, the development -cs- → /xs/ → /is/ and -ct- → /xt/ → /it/, the second common to much of Western Romance languages, also appears in inscriptions, e.g. Divicta ~ Divixta, Rectugenus ~ Rextugenus ~ Reitugenus, and is present in Welsh, e.g. *seχtan → saith "seven", *eχtamos → eithaf "extreme". For Romance, compare:

- Latin fraxinus "ash (tree)" → OFr fraisne (mod. frêne), Occitan fraisse, Catalan freixe, Portuguese freixo, Romansch fraissen (vs. Italian frassino, Romanian (dial.) frapsin, Spanish fresno).

- Latin lactem "milk" → French lait, Welsh llaeth, Portuguese leite, Catalan llet, Piemontese lait, Liguro leite (vs. Italian latte, Occitan lach, Lombardo làcc, Romansch latg, Spanish leche).

These two changes sometimes had a cumulative effect in French: Latin capsa → *kaχsa → caisse (vs. Italian cassa, Spanish caja) or captīvus → *kaχtivus → Occitan caitiu, OFr chaitif[12] (mod. chétif "wretched, feeble", cf. Welsh caeth "bondman, slave", vs. Italian cattivo, Spanish cautivo).

In French and adjoining folk dialects and closely related languages, some 200 words of Gaulish origin have been retained, most of which pertain to folk life. These include:

- land features (bief "reach, mill race", combe "hollow", grève "sandy shore", lande "heath");

- plant names (berle "water parsnip", bouleau "birch", bourdaine "black alder", chêne "oak", corme "service berry", gerzeau "corncockle", if "yew", vélar/vellar "hedge mustard");

- wildlife (alouette "lark", barge "godwit", loche "loach", pinson "finch", vandoise "dace", vanneau "lapwing");

- rural and farm life, most notably: boue "mud", cervoise "ale", charrue "plow", glaise "loam", gord "kiddle, stake net", jachère "fallow field", javelle "sheaf, bundle, fagot", marne "marl", mouton "sheep", raie "lynchet", sillon "furrow", souche "tree stump, tree base", tarière "auger, gimlet", tonne "barrel";

- some common verbs (braire "to bray", changer "to change", craindre "to fear", jaillir "to surge, gush").;[13] and

- loan translations: aveugle "blind", from Latin ab oculis "eyeless", calque of Gaulish exsops "blind", literally "eyeless"[14][15] (vs. Latin caecus → OFr cieu, It. cieco, Sp. ciego, or orbus → Occ. òrb, Venetian orbo, Romanian orb).

Other Celtic words were not borrowed directly, but brought in through Latin, some of which had become commonplace in Latin, as for instance braies "knee-length pants", chainse "tunic", char "dray, wagon", daim "roe deer", étain "tin", glaive "broad sword", manteau "coat", vassal "serf, knave". Latin quickly took hold among the urban aristocracy for mercantile, official, and educational reasons, but did not prevail in the countryside until some four or five centuries later, since Latin was of little or no social value to the landed gentry and peasantry. The eventual spread of Latin can be attributed to social factors in the Late Empire such as the movement from urban-focused power to village-centered economies and legal serfdom.

Franks

From the 3rd century on, Western Europe was invaded by Germanic tribes from the north and east, and some of these groups settled in Gaul. In the history of the French language, the most important of these groups are the Franks in northern France, the Alemanni in the modern German/French border area (Alsace), the Burgundians in the Rhône (and the Saone) valley, and the Visigoths in the Aquitaine region and Spain. The Frankish language had a profound influence on the Latin spoken in their respective regions, altering both the pronunciation (especially the vowel system phonemes; e, eu, u, short o) and the syntax. They also introduced a number of new words (see List of French words of Germanic origin). Sources disagree on how much of the vocabulary of modern French (excluding French dialects) comes from Germanic words, ranging from just 500 words (≈1%)[16] (representing loans from ancient Germanic languages: Gothic and Frankish)[17] to 15% of modern vocabulary (representing all Germanic loans up to modern times: Gothic, Frankish, Old Norse/Scandinavian, Dutch, German and English)[18] to even higher if Germanic words coming from Latin and other Romance languages are taken into account. (Note: According to the Académie française, only 5% of French words come from English.)

Changes in lexicon/morphology/syntax:

- the name of the language itself, français, comes from Old French franceis/francesc (compare M. L. franciscus) from the Germanic frankisc "french, frankish" from Frank ('freeman'). The Franks referred to their land as Franko(n) which became Francia in Latin in the 3rd century (at that time, an area in Gallia Belgica, somewhere in modern-day Belgium or the Netherlands). The name Gaule ("Gaul") was also taken from the Frankish *Walholant ("Land of the Romans/Gauls").

- several terms and expressions associated with their social structure (baron/baronne, bâtard, bru, chambellan, échevin, félon, féodal, forban, gars/garçon, leude, lige, maçon, maréchal, marquis, meurtrier, sénéchal).

- military terms (agrès/gréer, attaquer, bière ["stretcher"], dard, étendard, fief, flanc, flèche, gonfalon, guerre, garder, garnison, hangar, heaume, loge, marcher, patrouille, rang, rattraper, targe, trêve, troupe).

- colors derived from Frankish and other Germanic languages (blanc/blanche, bleu, blond/blonde, brun, fauve, gris, guède).

- other examples among common words include abandonner, arranger, attacher, auberge, bande, banquet, bâtir, besogne, bille, blesser, bois, bonnet, bord, bouquet, bouter, braise, broderie, brosse, chagrin, choix, chic, cliché, clinquant, coiffe, corroyer, crèche, danser, échaffaud, engage, effroi, épargner, épeler, étal, étayer, étiquette, fauteuil, flan, flatter, flotter, fourbir, frais, frapper, gai, galant, galoper, gant, gâteau, glisser, grappe, gratter, gredin, gripper, guère, guise, hache, haïr, halle, hanche, harasser, héron, heurter, jardin, jauger, joli, laid, lambeau, layette, lécher, lippe, liste, maint, maquignon, masque, massacrer, mauvais, mousse, mousseron, orgueil, parc, patois, pincer, pleige, rat, rater, regarder, remarquer, riche/richesse, rime, robe, rober, saisir, salon, savon, soupe, tampon, tomber, touaille, trépigner, trop, tuyau and many words starting with a hard g (like gagner, garantie, gauche, guérir) or with an aspired h (haine, hargneux, hâte, haut)[19]

- endings in -ard (from Frankish hard: canard, pochard, richard), -aud (from Frankish wald: crapaud, maraud, nigaud), -an/-and (from old suffix -anc, -enc: paysan, cormoran, Flamand, tisserand, chambellan) all very common family name affixes for French names.

- endings in -ange (Eng. -ing, Grm. -ung; boulange/boulanger, mélange/mélanger, vidange/vidanger), diminutive -on (oisillon)

- many verbs ending in -ir (2nd group, see French conjugation) such as affranchir, ahurir, choisir, guérir, haïr, honnir, jaillir, lotir, nantir, rafraîchir, ragaillardir, tarir, etc.

- prefix mé(s)- (from Frankish "missa-", as in mésentente, mégarde, méfait, mésaventure, mécréant, mépris, méconnaissance, méfiance, médisance)

- prefix for-, four- as in forbannir, forcené, forlonger, (se) fourvoyer, etc. from Frankish fir-, fur- (cf German ver-; English for-). Merged with Old French fuers "outside, beyond" from Latin foris. Latin foris was not used as a prefix in Classical Latin, but appears as a prefix in Medieval Latin following the Germanic invasions.

- prefix en-, em- (which reinforced and merged with Latin in- "in, on, into") was extended to fit new formations not previously found in Latin. Influenced or calqued from Frankish *in- and *an-, usually with an intensive or perfective sense: emballer, emblaver, endosser, enhardir, enjoliver, enrichir, envelopper, etc.

- The syntax shows the systematic presence of a subject pronoun in front of the verb, as in the Germanic languages: je vois, tu vois, il voit, while the subject pronoun is optional – function of the parameter pro-drop – in most other Romance languages (as in Spanish veo, ves, ve).

- The inversion of subject-verb to verb-subject to form the interrogative is characteristic of the Germanic languages but is not found in any of the major Romance languages, except French (cf. Vous avez un crayon. vs. Avez-vous un crayon?: "Do you have a pencil?").

- The adjective placed in front of the noun is typical of Germanic languages, it is more frequent in French than in the other major Romance languages and occasionally compulsory (belle femme, vieil homme, grande table, petite table); when it is optional, it changes the meaning: grand homme ("great man") and le plus grand homme ("the greatest man") vs homme grand ("tall man") and l'homme le plus grand ("the tallest man"), certaine chose vs chose certaine. In Walloon, the order "adjective + noun" is the general rule, as in Old French and North Cotentin Norman.

- Several words calqued or modeled on corresponding terms in Germanic languages (bienvenue, cauchemar, chagriner, compagnon, entreprendre, manoeuvre, manuscrit, on, pardonner, plupart, sainfoin, tocsin, toujours).

The Frankish language had a determining influence on the birth of Old French, which in part explains why Old French is the earliest attested of the Romance languages (e.g. the Oaths of Strasbourg, Sequence of Saint Eulalia).[20] The new speech diverged quite markedly from the Latin, with which it was no longer mutually intelligible. The Old Low Frankish influence is also primarily responsible for the differences between the langue d'oïl and langue d'oc (Occitan) as well, because different parts of Northern France remained bilingual in Latin and Germanic for several centuries,[21] corresponding exactly to the places where the first documents in Old French were written. This Germanic language shaped the popular Latin spoken here and gave it a very distinctive character compared to the other future Romance languages. The very first noticeable influence is the substitution of a Germanic stress accent for the Latin melodic accent,[22] which resulted in diphthongization, distinction between long and short vowels, the loss of the unaccentuated syllable and of final vowels, e.g. Latin decima > F dîme (> E dime. Italian decima; Spanish diezmo); Vulgar Latin dignitate > OF deintié (> E dainty. Occitan dinhitat; Italian dignità; Spanish dignidad); VL catena > OF chaiene (> E chain. Occitan cadena; Italian catena; Spanish cadena). On the other hand, a common word like L aqua > Occitan aigue became OF ewe > F eau 'water' (and évier sink), likely influenced by the OS or OHG word pronunciation aha (PG *ahwo).

In addition, two new phonemes that no longer existed in Vulgar Latin were added: [h] and [w] (> OF g(u)-, ONF w- cf. Picard w-), e.g. VL altu > OF halt 'high' (influenced by OLF *hauh; ≠ Italian, Spanish alto; Occitan naut); VL vespa > F guêpe (ONF wespe; Picard wespe) 'wasp' (influenced by OLF *waspa; ≠ Occitan vèspa; Italian vespa; Spanish avispa); L viscus > F gui 'mistletoe' (influenced by OLF *wihsila 'morello', together with analogous fruits, when they are not ripe; ≠ Occitan vesc; Italian vischio); LL vulpiculu 'little fox' (from L vulpes 'fox') > OF g[o]upil (influenced by OLF *wulf 'wolf'; ≠ Italian volpe). Italian and Spanish words of Germanic origin borrowed from French or directly from Germanic also retain this [gw] and [g], cf. It, Sp. guerra 'war'. In these examples, we notice a clear consequence of bilingualism, which frequently alters the initial syllable of the Latin.

There is also the converse example, where the Latin word influences the Germanic one: framboise 'raspberry' from OLF *brambasi (cf. OHG brāmberi > Brombeere 'mulberry'; E brambleberry; *basi 'berry' cf. Got. -basi, Dutch bes 'berry') conflated with LL fraga or OF fraie ‘strawberry’, which explains the shift to [f] from [b], and in turn the final -se of framboise turned fraie into fraise (≠ Occitan fragosta 'raspberry', Italian fragola 'strawberry'. Portuguese framboesa 'raspberry' and Spanish frambuesa are from French).[23]

Philologists such as Pope (1934) estimate that still perhaps fifteen percent of the vocabulary of modern French derives from Germanic sources, though the proportion was larger in Old French, as the language was consequently re-Latinised and partly Italianised by clerics and grammarians in the Middle Ages and later. Nevertheless, a large number of words like haïr "to hate" (≠ Latin odiare > Italian odiare, Spanish odiar, Occitan asirar) and honte "shame" (≠ Latin vĕrēcundia > Occitan vergonha, Italian vergogna, Spanish vergüenza) remain common.

Urban T. Holmes Jr. estimated that German was spoken as a second tongue by public officials in western Austrasia and Neustria as late as the 850s, and that it completely disappeared as a spoken language from these regions only during the 10th century,[24] though some traces of Germanic elements still survive, especially in dialectal French (Poitevin, Norman, Burgundian, Walloon, Picard, etc.).

Normans and terms from the Low Countries

In 1204 AD, the Duchy of Normandy was integrated into the Crown lands of France, and many words were introduced into the French language from Norman of which about 150 words of Scandinavian origin[25] are still in use. Most of these words have to do with the sea and seafaring: abraquer, alque, bagage, bitte, cingler, équiper (to equip), flotte, fringale, girouette, guichet, hauban, houle, hune, mare, marsouin, mouette, quille, raz, siller, touer, traquer, turbot, vague, varangue, varech. Others pertain to farming and daily life: accroupir, amadouer, bidon, bigot, brayer, brette, cottage, coterie, crochet, duvet, embraser, fi, flâner, guichet, haras, harfang, harnais, houspiller, marmonner, mièvre, nabot, nique, quenotte, raccrocher, ricaner, rincer, rogue.

Likewise, words borrowed from Dutch deal mainly with trade, or are nautical in nature, but not always so: affaler, amarrer, anspect, bar (sea-bass), bastringuer, bière (beer), blouse (bump), botte, bouée, bouffer, boulevard, bouquin, cague, cahute, caqueter, choquer, diguer, drôle, dune, équiper (to set sail), frelater, fret, grouiller, hareng, hère, lamaneur, lège, manne, mannequin, maquiller, matelot, méringue, moquer, plaque, sénau, tribord, vacarme, as are words from Low German: bivouac, bouder, homard, vogue, yole, and English of this period: arlequin (from Italian arlecchino < Norman hellequin < OE *Herla cyning), bateau, bébé, bol (sense 2 ≠ bol < Lt. bolus), bouline, bousin, cambuse, cliver, chiffe/chiffon, drague, drain, est, groom, héler, merlin, mouette, nord, ouest, potasse, rade, rhum, sonde, sud, turf, yacht.

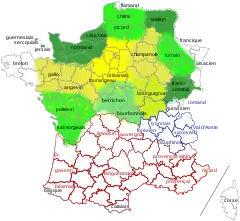

Langue d'oïl

The medieval Italian poet Dante, in his Latin De vulgari eloquentia, classified the Romance languages into three groups by their respective words for "yes": Nam alii oc, alii si, alii vero dicunt oil, "For some say oc, others say si, others say oïl". The oïl languages – from Latin hoc ille, "that is it" – occupied northern France, the oc languages – from Latin hoc, "that" – southern France, and the si languages – from Latin sic, "thus" – the Italian and Iberian peninsulas. Modern linguists typically add a third group within France around Lyon, the "Arpitan" or "Franco-Provençal language", whose modern word for "yes" is ouè.

The Gallo-Romance group in the north of France, the langue d'oïl like Picard, Walloon, and Francien, were influenced by the Germanic languages spoken by the Frankish invaders. From the time period of Clovis I on, the Franks extended their rule over northern Gaul. Over time, the French language developed from either the Oïl language found around Paris and Île-de-France (the Francien theory) or from a standard administrative language based on common characteristics found in all Oïl languages (the lingua franca theory).

Langue d'oc, the languages which use oc or òc for "yes", is the language group in the south of France and northernmost Spain. These languages, such as Gascon and Provençal, have relatively little Frankish influence.

The Middle Ages also saw the influence of other linguistic groups on the dialects of France:

Modern French, principally derived from the langue d'oïl acquired the word si, used to contradict negative statements or respond to negative questions, from cognate forms of "yes" in Spanish and Catalan (sí), Portuguese (sim), and Italian (sì).

From the 4th to 7th centuries, Brythonic-speaking peoples from Cornwall, Devon, and Wales traveled across the English Channel, both for reasons of trade and of flight from the Anglo-Saxon invasions of England. They established themselves in Armorica. Their language became Breton in more recent centuries, giving French bijou "jewel" (< Breton bizou from biz "finger") and menhir (< Breton maen "stone" and hir "long").

Attested since the time of Julius Caesar, a non-Celtic people who spoke a Basque-related language inhabited the Novempopulania (Aquitania Tertia) in southwestern France, while the language gradually lost ground to the expanding Romance during a period spanning most of the Early Middle Ages. This Proto-Basque influenced the emerging Latin-based language spoken in the area between the Garonne and the Pyrenees, eventually resulting in the dialect of Occitan called Gascon. Its influence is seen in words like boulbène and cargaison.

Scandinavian Vikings invaded France from the 9th century onwards and established themselves mostly in what would come to be called Normandy. The Normans took up the langue d'oïl spoken there, although Norman French remained heavily influenced by Old Norse and its dialects. They also contributed many words to French related to sailing (mouette, crique, hauban, hune, etc.) and farming.

After the conquest of England in 1066, the Normans's language developed into Anglo-Norman. Anglo-Norman served as the language of the ruling classes and commerce in England from the time of the conquest until the Hundred Years' War,[26] by which time the use of French-influenced English had spread throughout English society.

Around this time period, many words from the Arabic language (or from Persian via Arabic) entered French, mainly indirectly through Medieval Latin, Italian and Spanish. There are words for luxury goods (élixir, orange), spices (camphre, safran), trade goods (alcool, bougie, coton), sciences (alchimie, hasard), and mathematics (algèbre, algorithme). Only after the 19th century development of French colonies in North Africa did French borrow words directly from Arabic (e.g., toubib, chouia, mechoui).

Modern French

For the period up to around 1300, some linguists refer to the oïl languages collectively as Old French (ancien français). The earliest extant text in French is the Oaths of Strasbourg from 842; Old French became a literary language with the chansons de geste that told tales of the paladins of Charlemagne and the heroes of the Crusades.

The first government authority to adopt Modern French as official was the Aosta Valley in 1536, three years before France itself.[27] By the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts in 1539 King Francis I made French the official language of administration and court proceedings in France, ousting the Latin that had been used before then. With the imposition of a standardised chancery dialect and the loss of the declension system, the dialect is referred to as Middle French (moyen français). The first grammatical description of French, the Tretté de la Grammaire française by Louis Maigret, was published in 1550. Many of the 700 words [28] of modern French that originate from Italian were introduced in this period, including several denoting artistic concepts (scenario, piano), luxury items, and food. The earliest history of the French language and its literature was also written in this period: the Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poesie françoise, by Claude Fauchet, published in 1581.

Following a period of unification, regulation, and purification, the French of the 17th to the 18th centuries is sometimes referred to as Classical French (français classique), although many linguists simply refer to French language from the 17th century to today as Modern French (français moderne).

The foundation of the Académie française (French Academy) in 1634 by Cardinal Richelieu created an official body whose goal has been the purification and preservation of the French language. This group of 40 members is known as the Immortals, not, as some erroneously believe, because they are chosen to serve for the extent of their lives (which they are), but because of the inscription engraved on the official seal given to them by their founder Richelieu—"À l'immortalité" ("to [the] Immortality [of the French language]"). The foundation still exists and contributes to the policing of the language and the adaptation of foreign words and expressions. Some recent modifications include the change from software to logiciel, packet-boat to paquebot, and riding-coat to redingote. The word ordinateur for computer was however not created by the Académie, but by a linguist appointed by IBM (see fr:ordinateur).

From the 17th to the 19th centuries, France was the leading power of Europe; thanks to this, together with the influence of the Enlightenment, French was the lingua franca of educated Europe, especially with regards to the arts, literature, and diplomacy; monarchs like Frederick II of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia could both not just speak and write in French, but in most excellent French. The Russian, German and Scandinavian Courts spoke French as their main or official language, regarding their national languages as the language of the peasants. Spread of French to other European countries was also aided by emigration of persecuted Hugenots.[29]

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the French language established itself permanently in the Americas. There is an academic debate about how fluent in French the colonists of New France were. While less than 15% of colonists (25% of the women – chiefly filles du roi – and 5% of the men) were from the region of Paris and presumably spoke French, most of the rest came from north-western and western regions of France where regular French was not the primary native language. It is not clearly known how many among those colonists understood French as a second language, and how many among them – who, in overwhelming majority, natively spoke an oïl language – could understand, and be understood by, those who speak French thanks to interlinguistic similarity. In any case, a linguistic unification of all the groups coming from France happened (either in France, on the ships, or in Canada) such that, according to many sources, the then "Canadiens" were all speaking French (King's French) natively by the end of the 17th century, well before the unification was complete in France. Canada's reputation was to speak as good French as Paris did. Today, French is the language of about 10 million people (not counting French-based creoles, which are also spoken by about 10 million people) in the Americas.

Through the Académie, public education, centuries of official control and the role of media, a unified official French language has been forged, but there remains a great deal of diversity today in terms of regional accents and words. For some critics, the "best" pronunciation of the French language is considered to be the one used in Touraine (around Tours and the Loire valley), but such value judgments are fraught with problems, and with the ever-increasing loss of lifelong attachments to a specific region and the growing importance of the national media, the future of specific "regional" accents is often difficult to predict. The French nation-state, which appeared after the 1789 French Revolution and Napoleon's empire, unified the French people in particular through the consolidation of the use of the French language. Hence, according to historian Eric Hobsbawm, "the French language has been essential to the concept of 'France', although in 1789 50% of the French people did not speak it at all, and only 12 to 13% spoke it 'fairly' – in fact, even in oïl language zones, out of a central region, it was not usually spoken except in cities, and, even there, not always in the faubourgs [approximatively translatable to "suburbs"]. In the North as in the South of France, almost nobody spoke French."[30] Hobsbawm highlighted the role of conscription, invented by Napoleon, and of the 1880s public instruction laws, which allowed to mix the various groups of France into a nationalist mold which created the French citizen and his consciousness of membership to a common nation, while the various "patois" were progressively eradicated.

Modern issues

There is some debate in today's France about the preservation of the French language and the influence of English (see Franglais), especially with regard to international business, the sciences, and popular culture. There have been laws (see Toubon law) enacted which require that all print ads and billboards with foreign expressions include a French translation and which require quotas of French-language songs (at least 40%) on the radio. There is also pressure, in differing degrees, from some regions as well as minority political or cultural groups for a measure of recognition and support for their regional languages.

Once the key international language in Europe, being the language of diplomacy from the 17th to mid-20th centuries, French lost most of its international significance to English in the 20th century, especially after World War II, with the rise of the United States as a dominant global superpower. A watershed was when the Treaty of Versailles, ending World War I, was written in both French and English. A small but increasing number of large multinational firms headquartered in France are using English as their working language even in their French operations, and to gain international recognition, French scientists often publish their work in English. These trends have met some resistance. In March 2006, President Chirac briefly walked out of an EU summit after Ernest-Antoine Seilliere began addressing the summit in English.[31] And in February 2007, Forum Francophone International began organising protests against the "linguistic hegemony" of English in France and in support of the right of French workers to use French as their working language.[32]

French remains the second most-studied foreign language in the world, after English,[33] and is a lingua franca in some regions, notably in Africa. The legacy of French as a living language outside Europe is mixed: it is nearly extinct in some former French colonies (Southeast Asia), while the language has changed to creoles, dialects or pidgins in the French departments in the West Indies, even though people there are still educated in standard French.[34] On the other hand, many former French colonies have adopted French as an official language, and the total number of French speakers has increased, especially in Africa.

In the Canadian province of Quebec, different laws have promoted the use of French in administration, business and education since the 1970s. Bill 101, for example, obliges every child whose parents did not attend an English-speaking school to be educated in French. Efforts are also made, by the Office québécois de la langue française for instance, to make more uniform the variation of French spoken in Quebec as well as to preserve the distinctiveness of Quebec French.

There has been French emigration to the United States of America, Australia and South America, but the descendants of these immigrants have assimilated to the point that few of them still speak French. In the United States of America efforts are ongoing in Louisiana (see CODOFIL) and parts of New England (particularly Maine) to preserve the language there.[35]

Internal history

French has radically transformative sound changes, especially compared with other Romance languages such as Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and Romanian. Some examples:

| Latin | Written French | Spoken French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Romanian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CANEM "dog" | chien | /ʃjɛ̃/ | cane | can | cão | câine |

| OCTŌ "eight" | huit | /ɥit/ | otto | ocho | oito | opt |

| PĒRAM "pear" | poire | /pwaʁ/ | pera | pera | pera | pară |

| ADIŪTĀRE "to help" | aider | /ɛde/ | aiutare | ayudar | ajudar | ajuta |

| IACET "it lies (e.g. on the ground)" | gît | /ʒi/ | giace | yace | jaz | zace |

Vowels

The Vulgar Latin[lower-alpha 1] underlying French and most other Romance languages had seven vowels in stressed syllables (/a ɛ e i ɔ o u/, similar to the vowels of American English khat pet pate peat caught coat coot respectively), and five in unstressed syllables (/a e i o u/). Portuguese and Italian largely preserve this system, while Spanish has innovated only in converting /ɛ/ to /je/ and /ɔ/ to /we/, resulting in a simple five-vowel system /a e i o u/. In French, however, numerous sound changes resulted in a system with 12–14 oral vowels and 3–4 nasal vowels (see French phonology).

Perhaps the most salient characteristic of French vowel history is the development of a strong stress accent — usually ascribed to the influence of the Germanic languages — that led to the disappearance of most unstressed vowels and to pervasive differences in the pronunciation of stressed vowels in originally open vs. closed syllables (where a closed syllable is a syllable that was followed by two or more consonants in Vulgar Latin, whereas an open syllable was followed by at most one consonant). It is commonly thought that stressed vowels in open syllables were lengthened, after which most of the long vowels turned into diphthongs. The loss of unstressed vowels, particularly those after the stress, ultimately produced the situation in Modern French where the accent is uniformly found on the last syllable of a word. (Ironically, in Modern French the stress accent is quite weak, with little difference between the pronunciation of stressed and unstressed vowels.)

Unstressed vowels

Vulgar Latin had five vowels in unstressed syllables: /a e i o u/. When these occurred word-finally, all were lost in Old French except for /a/, which turned into a schwa (written e):

| Latin | Vulgar Latin | French |

|---|---|---|

| FACTAM "done (fem.)" | /fákta/ | faite |

| NOCTEM "night" | /nɔ́kte/ | nuit |

| DĪXĪ "I said" | /díksi/ | dis |

| OCTŌ "eight" | /ɔ́kto/ | huit |

| FACTUM "done (masc.)" | /fáktu/ | fait |

A final schwa also developed when the loss of a final vowel produced a consonant cluster that was (at the time) unpronounceable when word-final, usually consisting of a consonant followed by l, r, m or n (VL = Vulgar Latin, OF = Old French):

- POPULUM "people" > peuple

- INTER "between" > VL */entre/ > entre

- PATER "father" > VL */patre/ > père[lower-alpha 2]

- ASINUM "donkey" > OF asne > âne

The final schwa was eventually lost as well, but leaves its mark in the spelling, as well as in the pronunciation of final consonants, which normally remain pronounced if a schwa followed but are often lost otherwise: fait "done (masc.)" /fɛ/ vs. faite "done (fem.)" /fɛt/.

Intertonic vowels (i.e. unstressed vowels in interior syllables) were lost entirely, except for a in a syllable preceding the stress, which (originally) became a schwa (stressed syllable underlined in the Latin examples):

- POPULUM "people" > peuple

- ASINUM "donkey" > OF asne > âne

- PRESBYTER "priest" > VL */prɛ́sbetre/ > OF prestre > prêtre

- QUATTUORDECIM "fourteen" > VL */kwattɔ́rdetsi/ > quatorze

- STEPHANUM "Stephen" > VL */estɛ́fanu/ > OF Estievne > Étienne

- SEPTIMANAM "week" > VL */settemána/ > semaine

- *PARABOLĀRE "to speak" > VL */parauláre/ > parler

- SACRAMENTUM "sacrament" > OF sairement > serment "oath[lower-alpha 3]

- ADIŪTĀRE "to help" > aider

- DISIĒIŪNĀRE "to break one's fast" > OF disner > dîner "to dine"

Stressed vowels

As noted above, stressed vowels developed quite differently depending on whether they occurred in an open syllable (followed by at most one consonant) or a closed syllable (followed by two or more consonants). In open syllables, the Vulgar Latin mid vowels /ɛ e ɔ o/ all diphthongized, becoming Old French ie oi ue eu respectively (ue and eu later merged), while Vulgar Latin /a/ was raised to Old French e. In closed syllables, all Vulgar Latin vowels originally remained unchanged, but eventually /e/ merged into /ɛ/, while /u/ became the front rounded vowel /y/ and /o/ was raised to /u/. (These latter two changes occurred unconditionally, i.e. in both open and closed, stressed and unstressed syllables.)

The following table shows the outcome of stressed vowels in open syllables:

| Vulgar Latin | Old French | Modern French spelling | Modern French pronunciation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | e | e, è | /e/, /ɛ/ | MARE "sea" > mer, TALEM "such" > tel, NĀSUM "nose" > nez, NATUM "born" > né |

| /ɛ/ | ie | ie | /je/, /jɛ/ | HERI "yesterday" > hier, *MELEM "honey" > miel, PEDEM "foot" > pied |

| /e/ | oi | oi | /wa/ | PĒRA pear > poire, PILUM "hair" > poil, VIAM "way" > voie |

| /i/ | i | i | /i/ | FĪLUM "wire" > fil, VĪTA "life" > vie |

| /ɔ/ | ue | eu, œu | /ø/, /œ/ | *COREM "heart" > OF cuer > cœur, NOVUM "new" > OF nuef > neuf |

| /o/ | eu | eu, œu | /ø/, /œ/ | HŌRA "hour" > heure, GULA "throat" > gueule |

| /u/ | u | u | /y/ | DŪRUM "hard" > dur |

The following table shows the outcome of stressed vowels in closed syllables:

| Vulgar Latin | Old French | Modern French spelling | Modern French pronunciation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | a | a | /a/ | PARTEM "part" > part, CARRUM "carriage" > char, VACCAM "cow" > vache |

| /ɛ/ | e | e | /ɛ/ | TERRAM "land" > terre, SEPTEM "seven" > VL /sɛtte/ > OF set > sept /sɛt/[lower-alpha 4] |

| /e/ | e | e | /ɛ/ | SICCUM dry > sec |

| /i/ | i | i | /i/ | VĪLLAM "estate" > ville "town" |

| /ɔ/ | o | o | /ɔ/, /o/ | PORTUM "port" > port, SOTTUM "foolish" > sot |

| /o/ | o | ou | /u/ | CURTUM "short" > court, GUTTAM "drop (of liquid)" > OF gote > goutte[36] |

| /u/ | u | u | /y/ | NŪLLUM "none" > nul |

Nasal vowels

Latin N that ended up not followed by a vowel after the loss of vowels in unstressed syllables was ultimately absorbed into the preceding vowel, producing a series of nasal vowels. The developments are somewhat complex (even more so when a palatal element is also present in the same cluster, as in PUNCTUM "point, dot" > point /pwɛ̃/). There are two separate cases, depending on whether the N originally stood between vowels or next to a consonant (i.e. whether a preceding stressed vowel developed in an open syllable or closed syllable context, respectively). See the article on the phonological history of French for full details.

Long vowels

Latin S before a consonant ultimately was absorbed into the preceding vowel, producing a long vowel (indicated in Modern French spelling with a circumflex accent). For the most part, these long vowels are no longer pronounced distinctively long in Modern French (although long ê is still distinguished in Quebec French). In most cases, the formerly long vowel is pronounced identically to the formerly short vowel (e.g. mur "wall" and mûr "mature" are pronounced the same), but some pairs are distinguished by their quality (e.g. o /ɔ/ vs. ô /o/).

A separate, later vowel lengthening operates allophonically in Modern French, lengthening vowels before the final voiced fricatives /v z ʒ ʁ vʁ/ (e.g. paix /pɛ/ "peace" vs. pair [pɛːʁ] "even").

Effect of palatalized consonants

Late Vulgar Latin of the French area had a full complement of palatalized consonants, and more developed over time. Most of them, if preceded by a vowel, caused a /j/ sound (a yod, as in the words you or yard) to appear before them, which combined with the vowel to produce a diphthong, eventually developing in various complex ways. A /j/ also appeared after them if they were originally followed by certain stressed vowels in open syllables (specifically, /a/ or /e/). If the appearance of the /j/ sound produced a triphthong, the middle vowel dropped out.

Examples, showing the various sources of palatalized consonants:

- From Latin E or I in hiatus:

- BASSIĀRE "to lower" > VL */bassʲare/ > OF baissier > baisser[lower-alpha 5]

- PALĀTIUM "palace" > VL */palatsʲu/ > palais

- From Latin C or G followed by a front vowel (i.e. E or I):

- PĀCEM "peace" > VL */patsʲe/ > paix

- CĒRA "wax" > VL */tsʲera/ > */tsjejra/ > cire[lower-alpha 6]

- From Latin sequences such as CT, X, GR:

- FACTUM "done" > Western Vulgar Latin */fajtʲu/ > fait

- LAXĀRE "to release" > Western Vulgar Latin */lajsʲare/ > OF laissier > laisser "to let"[lower-alpha 7]

- NIGRUM "black" > Western Vulgar Latin */nejrʲu/ > Early Old French neir > noir[lower-alpha 8]

- NOCTEM "night" > Western Vulgar Latin */nɔjtʲe/ > */nwɔjtʲe/ > */nujtʲe/ nuit[lower-alpha 9]

- From Latin C or G followed by /a/, when not preceded by a vowel:

- CANEM "dog" > pre-French */tʃʲane/ > chien

- CARRICĀRE "to load" > Western Vulgar Latin */karregare/ > */kargare/ > pre-French */tʃʲardʒʲare/ > OF chargier

- From Latin consonantal I:

- PĒIOR /pejjor/ "worse" > Western Vulgar Latin */pɛjrʲe/ > pre-French */pjɛjrʲe > pire[lower-alpha 10]

- IACET "he lies (on the ground)" > pre-French */dʒʲatsʲet/ > */dʒjajtst/ > OF gist > gît[lower-alpha 11]

Effect of l

During the Old French period, l before a consonant became u, producing new diphthongs, which eventually resolved into monophthongs, e.g. FALSAM "false" > fausse /fos/. See the article on phonological history of French for details.

Consonants

The sound changes involving consonants are less striking than those involving vowels. In some ways, French is actually relatively conservative. For example, it preserves initial pl-, fl-, cl-, unlike Spanish, Portuguese and Italian, e.g. PLOVĒRE "to rain" > pleuvoir (Spanish llover, Portuguese chover, Italian piovere).

Lenition

Consonants between vowels were subject to a process called lenition (a type of weakening). In French, this was more extensive than in Spanish, Portuguese or Italian. For example, /t/ between vowels went through the following stages in French: /t/ > /d/ > /ð/ > no sound, whereas in Spanish only the first two changes happened, in Brazilian Portuguese only the first change happened, and in Italian no changes happened. Compare VĪTAM "life" > vie with Italian vita, Portuguese vida, Spanish vida [biða]. The following table shows the outcomes:

| Vulgar Latin | French | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| /t/, /d/ | no sound | VĪTAM "life" > vie; CADĒRE "to fall" > OF cheoir > choir |

| /k/, /g/ | /j/ or no sound | PACĀRE "to pay" > payer; LOCĀRE "to put, to lease" > louer "to rent" |

| /p/, /b/, /f/, /v/ | /v/ or no sound | *SAPĒRE "to be wise" > savoir "to know"; DĒBĒRE "to have to" > devoir; *SAPŪTUM "known" > OF seü > su |

| /s/ | /z/ | CAUSAM "cause" > chose "thing" |

| /tsʲ/ | /z/ | POTIŌNEM "drink" > VL */potsʲone/ > poison "poison" |

Palatalization

As described above, Late Vulgar Latin of the French area had an extensive series of palatalized consonants that developed from numerous sources. The resulting sounds tended to eject a /j/ before and/or after them, forming diphthongs that later developed in complex ways.

Latin E and I in hiatus position (i.e., directly followed by another vowel) developed into /j/ in Vulgar Latin and then combined with the preceding consonant to form a palatalized consonant. All consonants could be palatalized in this fashion. The resulting consonants developed as follows (sometimes developing differently when they became final as a result of early loss of the following vowel):

| Vulgar Latin | French, non-final | French, final | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| */tj/ > */tsʲ/ | (i)s | POTIŌNEM "drink" > poison "poison"; PALĀTIUM "palace" > palais | |

| */kj/, */ttj/, */kkj/, */ktj/ > */ttsʲ/ | c, ss | OF z > s | *FACIAM "face" > face; BRACCHIUM "arm" > OF braz > bras, *PETTIAM "piece" > pièce, *DĪRECTIĀRE "to set, to erect" > OF drecier > dresser[lower-alpha 12] |

| */dj/, */gj/ > */jj/ | i | *GAUDIAM "joy" > joie; MEDIUM "middle" > mi | |

| */sʲ/ | (i)s | BASIĀRE "to kiss" > baiser | |

| */ssʲ/ | (i)ss | (i)s | BASSIĀRE "to lower" > baisser |

| */lʲ/ | ill | il | PALEAM "straw" > paille; *TRIPĀLIUM "instrument of torture" > travail "work"[lower-alpha 13] |

| */nʲ/ | gn | (i)n | *MONTĀNEAM "mountainous" > montagne "mountain"; BALNEUM "bath" > VL */banju/ > bain[lower-alpha 14] |

| */rʲ/ | (i)r or (ie)r[lower-alpha 15] | ĀREAM "threshing floor, open space" > aire; OPERĀRIUM "worker" > ouvrier | |

| /mʲ/ | ng /nʒ/ | ? | VĪNDĒMIA "vintage" > OF vendenge > vendange |

| /pʲ/ | ch | ? | SAPIAM "I may be wise" > (je) sache "I may know" |

| /bʲ/, /vʲ/, /fʲ/ | g /ʒ/ | *RABIAM "rage" > rage; RUBEUM "red" > rouge | |

C followed by E or I developed into Vulgar Latin */tsʲ/, which was lenited to */dzʲ/ between vowels (later -is-). The pronunciation /ts/ was still present in Old French, but was subsequently simplified to /s/. Examples:

- CENTUM "hundred" > cent

- PLACĒRE "to please" > plaisir "pleasure"

- PĀCEM "peace" > OF pais > paix

G followed by E or I developed originally into Vulgar Latin */j/, which subsequently became /dʒʲ/ when not between vowels. The pronunciation /dʒ/ was still present in Old French, but was subsequently simplified to /ʒ/. When between vowels, /j/ often disappeared. Examples:

- GENTĒS "people" > gents > gents

- RĒGĪNA "queen" > OF reïne > reine

- QUADRĀGINTĀ "forty" > quarante

- LEGERE "to read" > pre-French */ljɛjrʲe/ > lire[lower-alpha 16]

C and G when followed by A and not preceded by a vowel developed into /tʃʲ/ and /dʒʲ/, respectively. The sounds /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ persisted into the Old French period but were subsequently simplified to /ʃ/ and /ʒ/. Examples:

- CARRUM "chariot" > char

- GAMBAM "leg" > jambe

- MANICAM "sleeve" > */manka/ > manche

- SICCAM "dry (fem.)" > sèche

In various consonant combinations involving C or G + another consonant, the C or G developed into /j/, which proceeded to palatalize the following consonant. Examples:

- FACTUM "done" > fait

- LAXĀRE "to release" > OF laissier "to let" > laisser

- VETULAM "old" > VECLAM > OF vieille

- ARTICULUM "joint" > VL */arteklu/ > orteil "toe"

- VIGILĀRE "to keep watch" > OF veillier > veiller

In some cases, loss of an intertonic vowel led to a similar sequence of /j/ or palatalized consonant + another consonant, which was palatalized in turn. Examples:

- MEDIETĀTEM "half" > */mejjetate/ > */mejtʲat/ > moitié

- CŌGITĀRE "to think" >> *CŪGITĀRE > */kujetare/ > Western Vulgar Latin */kujedare/ > pre-French */kujdʲare/ > OF cuidier > cuider

- *MĀNSIŌNĀTAM "household" > OF maisniée

- *IMPĒIORĀRE "to worsen" > OF empoirier

Changes to final consonants

As a result of the pre-French loss of most final vowels, all consonants could potentially appear word-finally except for /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ (which were always followed by at least a schwa, stemming from either a final /a/ or a prop vowel). In Old French, however, all underlying voiced stops and fricatives were pronounced voiceless when word-final. This was clearly reflected in Old French spelling, e.g. the adjectives froit "cold" (feminine froide), vif "lively" (feminine vive), larc "large" (feminine large), and similarly in verbs, e.g. je doif "I must" vs. ils doivent "they must", je lef "I may wash" vs. ils levent "they (may) wash". Most of these alternations have since disappeared (due partly to morphological reshaping and partly to respelling once most final consonants were lost, as described below), but the adjectival alternation vif vs. vive (and similarly for other adjectives in -f) is still present.

Starting in the Middle French period, most final consonants were gradually lost. This proceeded in stages:

- Loss of final consonants when appearing before another word beginning with a consonant. This stage is preserved in the words six and dix, pronounced /sis/ /dis/ standing alone but /si/ /di/ before a word beginning with a consonant and /siz/ /diz/ before a word beginning with a vowel. If the word ended in a stressed vowel followed by /s/ (as, for example, in plurals), the same process apparently operated as elsewhere when an /s/ preceded a consonant, with a long vowel resulting. (This situation is still found, for example, in Jèrriais, a dialect of the Norman language, which preserves long vowels and where words ending in a vowel lengthen that vowel in the plural.)

- Loss of final consonants before a pause. This left a two-way pronunciation for most words, with final consonants pronounced before a following vowel-initial word but not elsewhere, and is the origin of the modern phenomenon of liaison.

- Loss of final consonants in all circumstances. This process is still ongoing, causing a gradual loss of liaison, especially in informal speech, except in certain limited contexts and fixed expressions.

The final consonants normally subject to loss are /t/, /s/, /p/, sometimes /k/ and /r/, rarely /f/ (e.g. in clé < earlier and still occasional clef). The consonants /l/ and /ʎ/ were normally preserved, while /m/, /n/, /ɲ/ and /ʃ/ did not occur (nor did the voiced obstruents /d z b g v ʒ/). A more recent countervailing tendency, however, is the restoration of some formerly lost final consonants, as in sens, now pronounced /sɑ̃s/ but formerly /sɑ̃/, as still found in the expressions sens dessus dessous "upside down" and sens devant derrière "back to front". The restored consonant may stem either from the liaison pronunciation or the spelling and serves to reduce ambiguity: for example, /sɑ̃/ is also the pronunciation of cent "hundred", sang "blood" and sans "without" (among others).

Effect of substrate and superstrate languages

French is noticeably different from most other Romance languages. Some of the changes have been attributed to substrate influence – i.e., to carry-over effects from Gaulish (Celtic) or superstrate influence from Frankish (Germanic). In practice, it is difficult to say with confidence which sound and grammar changes were due to substrate and superstrate influences, since many of the changes in French have parallels in other Romance languages, or are changes commonly undergone by many languages in the process of development. However, the following are likely candidates.

In phonology:

- The reintroduction of the consonant /h/ at the beginning of a word is due to Frankish influence, and mostly occurs in words borrowed from Germanic. This sound no longer exists in Standard Modern French (it survives dialectally, particularly in the regions of Normandy, Picardy, Wallonia, and Louisiana); however a Germanic h usually disallows liaison: les halles /le.al/, les haies /le.ɛ/, les haltes /le.alt/, whereas a Latin h allows liaison: les herbes /lezɛrb/, les hôtels /lezotɛl/.

- The reintroduction of /w/ in Northern Norman, Picard, Walloon, Champenois, Bourguignon and Bas-Lorrain[37] is due to Germanic influence. All Romance languages have borrowed Germanic words containing /w/, but all languages south of the isogloss – including the ancestor of Modern French ("Central French") – converted this to /ɡw/, which usually developed subsequently into /ɡ/. English borrowed words both from Norman French (1066 – c. 1200 AD) and Standard French (c. 1200–1400 AD), which sometimes results in doublets such as warranty and guarantee or warden and guardian.

- The occurrence of an extremely strong stress accent, leading to loss of unstressed vowels and extensive modification of stressed vowels (diphthongization), is likely to be due to Frankish influence, and possibly to Celtic influence, as both languages had a strong initial stress (e. g., tela -> TEla -> toile)[38] This feature also no longer exists in Modern French. However, its influence remains in the uniform final word stress in Modern French – due to the strong stress, all vowels following the stress were ultimately lost.

- Nasalization resulting from compensatory vowel lengthening in stressed syllables due to Germanic and/or Celtic stress accent. Among Romance languages, it occurs primarily in French, Occitan, Arpitan and Portuguese, all with possible Celtic substratums. However scattered dialects of Romance languages, including Sardinian, Spanish and Lombard, also have the phenomenon as an allophonic (though not phonemic) property. Among the four Romance languages where it is prominent beyond divergent dialects, the only one for which it is undebatably phonemic is French[39]

- The development of front-rounded vowels /y/, /ø/, and /œ/ may be due to Germanic influence, as few Romance languages outside of French have such vowels; however, all Gallo-Romance languages have them and also share a Germanic influence. At least one sound, /y/, exists in today's Celtic languages. A number of other scholars, most famously including Romance linguist Ascoli, have attributed it to the Celtic substratum.[40] The attribution of the sounds to Celtic influence actually predates the emergence of academic linguistics as early as the 1500s, when it was attested as being called "Gaulish u". Among Romance languages, its distribution strongly correspondent with areas of suspected Celtic substratum: French, Arpitan, Occitan, Romansch and Gallo-Italic dialects, along with some dialects of Portuguese. The change may have occurred around the same time as a similar fronting of long [u] to [y] in the British Celtic languages. On the other hand, there are scholars such as Posner and Meyer-Lübke who, while acknowledging the possibility of Celtic influence, see the development as internally motivated.[41][42]

- The lenition of intervocalic consonants (see above) may be due to Celtic influence: A similar change happened in Celtic languages at about the same time, and the demarcation between Romance dialects with and without this change (the La Spezia–Rimini Line) corresponds closely to the limit of Celtic settlement in ancient Rome. The lenition also affected later words borrowed from Germanic (e.g. haïr < hadir < *hatjan; flan < *fladon; (cor)royer < *(ga)rēdan; etc.), suggesting that the tendency persisted for some time after it was introduced.

- The devoicing of word final voiced consonants in Old French is due to Germanic influence (e.g. grant/grande, blont/blonde, bastart/bastarde).

In other areas:

- Various words may have shifted gender under the influence from words either of the same meaning or similar sound in Gaulish, as a result of the Celtic substrate. A connectionist model predicting shifts in gender assignment for common nouns more accurately predicted historical developments when the Gaulish genders of the same words were considered in the model. Additionally the loss of the neuter may have been accelerated in French because Gaulish neuters were very hard to distinguish and possibly lost earlier than Latin neuters.[43] For comparison, Romanian retains the neuter gender and Italian retains it for a couple words; Portuguese, Sardinian, Catalan, and Spanish also retain remnants of the neuter outside of nouns in demonstrative pronouns and the like though they have lost it for nouns.

- The development of verb-second syntax in Old French (where the verb must come in second position in a sentence, regardless of whether the subject precedes or follows) is probably due to Germanic influence.

- The first person plural ending -ons (Old French -omes, -umes) is likely derived from the Frankish termination -ōmês, -umês (vs. Latin -āmus, -ēmus, -imus, and -īmus; cf. OHG -ōmēs, -umēs).[44]

- The use of the letter k in Old French, which was replaced by c and qu during the Renaissance, was due to Germanic influence. Typically, k was not used in written Latin and other Romance languages. Similarly, use of w and y was also diminished.

- The impersonal pronoun on "one, you, they" but more commonly replacing nous "we" (or "us") in colloquial French (first person plural pronoun, see Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law) – from Old French (h)om, a reduced form of homme "man" is a calque of the Germanic impersonal pronoun man "one, you, they" reduced form of mann "man" (cf Old English man "one, you, they", from mann "man"; German man "one, you, they" vs. Mann "man").

- The expanded use of avoir "to have" over the more customary use of tenir "to have, hold" seen in other Romance languages is likely to be due to influence from the Germanic word for "have", which has a similar form (cf. Frankish *habēn, Gothic haban, Old Norse hafa, English have).

- The increased use of auxiliary verbal tenses, especially passé composé, is probably due to Germanic influence. Unknown in Classical Latin, the passé composé begins to appear in Old French in the early 13th century after the Germanic and the Viking invasions. Its construction is identical to the one seen in all other Germanic languages at that time and before: "verb "be" (être) + past participle" when there is movement, indication of state, or change of condition; and ""have" (avoir) + past participle" for all other verbs. Passé composé is not universal to the Romance language family – only Romance languages known to have Germanic superstrata display this type of construction, and in varying degrees (those nearest to Germanic areas show constructions most similar to those seen in Germanic). Italian, Spanish and Catalan are other Romance languages employing this type of compound verbal tense.

- The heightened frequency of si ("so") in Old French correlates to Old High German so and thanne

- The tendency in Old French to use adverbs to complete the meaning of a verb, as in lever sur ("raise up"), monter en amont ("mount up"), aller avec ("go along/go with"), traire avant ("draw forward"), etc. is likely to be of Germanic origin

- The lack of a future tense in conditional clauses is likely due to Germanic influence.

- The reintroduction of a vigesimal system of counting by increments of 20 (e.g. soixante-dix "70" lit. "sixty-ten"; quatre-vingts "80" lit. "four-twenties"; quatre-vingt-dix "90" lit. "four-twenty-ten") is due to North Germanic influence, first appearing in Normandy, in northern France. From there, it spread south after the formation of the French Republic, replacing the typical Romance forms still used today in Belgian and Swiss French. The current vigesimal system was introduced by the Vikings and adopted by the Normans who popularised its use (compare Danish tresindstyve, literally 3 times 20, or 60; English four score and seven for 87). Pre-Roman Celtic languages in Gaul also made use of a vigesimal system, but this system largely vanished early in French linguistic history or became severely marginalised in its range. The Nordic vigesimal system may possibly derive ultimately from the Celtic. Old French also had treis vingts, cinq vingts (compare Welsh ugain "20", deugain "40", pedwar ugain "80", lit. "four-twenties").

See also

- Old French

- Old Frankish

- Gaulish

- Reforms of French orthography

- Influence of French on English

- Vulgar Latin

- History of the Spanish language

- History of the Portuguese language

- History of the Italian language

- History of the English language

- Language policy in France

- List of French words of Germanic origin

Notes

- For the purposes of this article, "Vulgar Latin" refers specifically to the spoken Latin that underlies French, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese, technically termed Proto-Italo-Western-Romance.

- Note how a final schwa appears even though the t was eventually lost.

- The word has been respelled in Modern French, but the Old French result shows that a in an intertonic syllable preceding the stress was originally preserved as a schwa.

- The p is etymological only.

- Here, /j/ appeared both before and after the palatalized sound, but Old French infinitives in -ier were later converted to end in -er.

- Stressed /e/ in an open syllable normally develops to Early Old French ei, later oi. In this case, however, the /j/ produced by Vulgar Latin /tsʲ/ produced a triphthong /jej/, which simplified to /i/ by loss of the middle vowel /e/.

- See note above about baisser.

- The resulting sequence ei developed the same way as ei from stressed open /e/.

- VL /ɔ/ normally becomes diphthongal /wɔ/ in open syllables, later becoming Old French ue. However, diphthongization of /ɔ/ and /ɛ/ also occurred in closed syllables when a palatalized consonant followed, and the resulting triphthong was simplified by loss of the middle vowel.

- Here triphthong reduction produces /i/ by deleting the middle vowel /ɛ/.

- Here a triphthong results from the combined effects of the two palatalized consonants, and is then reduced to /i/ by loss of the middle vowel /a/.

- Note that no /j/ was ejected before the palatalized consonant in this case.

- No /j/ was ejected before the palatalized consonant; the i in il(l) is purely a spelling construct. This probably stems from the consonant originally being pronounced geminated, as it still is in modern Italian.

- No /j/ was ejected before the palatalized consonant except word-finally. This may stem from the consonant originally being pronounced geminated, as it still is in modern Italian.

- A /j/ was ejected before the consonant as expected, except that VL */arʲ/ > ier.

- See above.

References

- Vincent Herschel Malmström, Geography of Europe: A Regional Analysis

- Roger Collins, The Basques, Blackwell, 1990.

- Barry Raftery & Jane McIntosh, Atlas of the Celts, Firefly Books, 2001

- Laurence Hélix. Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5.

Le déclin du Gaulois et sa disparition ne s'expliquent pas seulement par des pratiques culturelles spécifiques: Lorsque les Romains conduits par César envahirent la Gaule, au 1er siecle avant J.-C., celle-ci romanisa de manière progressive et profonde. Pendant près de 500 ans, la fameuse période gallo-romaine, le gaulois et le latin parlé coexistèrent; au VIe siècle encore; le temoignage de Grégoire de Tours atteste la survivance de la langue gauloise.

- Hist. Franc., book I, 32 Veniens vero Arvernos, delubrum illud, quod Gallica lingua Vasso Galatæ vocant, incendit, diruit, atque subvertit. And coming to Clermont [to the Arverni] he set on fire, overthrew and destroyed that shrine which they call Vasso Galatæ in the Gallic tongue.

- R. Anthony Lodge, French: From Dialect to Standard (Routledge, 1993).

- Giovanni Battista Pellegrini, "Substrata", in Romance Comparative and Historical Linguistics, ed. Rebecca Posner et al. (The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter, 1980), 65.

- Henri Guiter, "Sur le substrat gaulois dans la Romania", in Munus amicitae. Studia linguistica in honorem Witoldi Manczak septuagenarii, eds., Anna Bochnakowa & Stanislan Widlak, Krakow, 1995.

- Eugeen Roegiest, Vers les sources des langues romanes: Un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania (Leuven, Belgium: Acco, 2006), 83.

- Jean-Paul Savignac, Dictionnaire français-gaulois, s.v. "trop, très" (Paris: La Différence, 2004), 294–5.

- Pierre-Yves Lambert, La Langue gauloise (Paris: Errance, 1994), 46–7. ISBN 978-2-87772-224-7

- Lambert 46–47

- "Mots francais d'origine gauloise". Mots d'origine gauloise. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- Calvert Watkins, "Italo-Celtic revisited", in H. Birnbaum, J. Puhvel, ed, Ancient Indo-European Dialects, Berkeley-Los Angeles 1966, p. 29-50.

- Lambert 158.

- Henriette Walter, Gérard Walter, Dictionnaire des mots d’origine étrangère, Paris, 1998

- "The History of the French Language". Catholic Central French. Archived from the original on 16 August 2006. Retrieved 22 March 2006.

- Walter & Walter 1998.

- Le trésor de la langue française informatisé

- Bernard Cerquiglini, La naissance du français, Presses Universitaires de France, 2nd Edition 1993, C. III, p. 53.

- Cerquiglini 53

- Cerquiglini 26.

- Etymology of frambuesa (Spanish)

- Urban T. Holmes Jr., A. H. Schutz (1938), A history of the French language, p. 29, Biblo & Tannen Publishers, ISBN 0-8196-0191-8

- Elisabeth Ridel, Les Vikings et les mots, Editions Errance, 2010

- Baugh, Cable, "A History of the English Language, 104."

- La Vallée d'Aoste : enclave francophone au sud-est du Mont Blanc.

- Henriette Walter, L'aventure des mots français venus d'ailleurs, Robert Laffont, 1998.

- Marc Fumaroli (2011). When The World Spoke French. Translated by Richard Howard. ISBN 978-1590173756.

- Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism since 1780 : programme, myth, reality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990; ISBN 0-521-43961-2) chapter II "The popular protonationalism", pp.80–81 French edition (Gallimard, 1992). According to Hobsbawm, the main source for this subject is Ferdinand Brunot (ed.), Histoire de la langue française, Paris, 1927–1943, 13 volumes, in particular volume IX. He also refers to Michel de Certeau, Dominique Julia, Judith Revel, Une politique de la langue: la Révolution française et les patois: l'enquête de l'abbé Grégoire, Paris, 1975. For the problem of the transformation of a minority official language into a widespread national language during and after the French Revolution, see Renée Balibar, L'Institution du français: essai sur le co-linguisme des Carolingiens à la République, Paris, 1985 (also Le co-linguisme, PUF, Que sais-je?, 1994, but out of print) ("The Institution of the French language: essay on colinguism from the Carolingian to the Republic. Finally, Hobsbawm refers to Renée Balibar and Dominique Laporte, Le Français national: politique et pratique de la langue nationale sous la Révolution, Paris, 1974.

- Anonymous, "Chirac upset by English address," BBC News, 24 March 2006.

- Anonymous, "French fury over English language," BBC News, 8 February 2007.

- "DIFL". Learn Languages. Dante Institute of Foreign Languages. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- "Sain Lucian Creole French". Ethnologue. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- "Cultural Organisations". Maine Acadian Culture Preservation Commission. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- The second t is etymological only.

- Jacques Allières, La formation du Français, P. U. F.

- Cerquiglini, Bernard. Une langue orpheline, Éd. de Minuit, 2007.

- Rebecca Posner. The Romance Languages. pp. 24–29.

- Craddock, Jerry Russell. Latin Legacy Versus Substratum Residue. p. 18.

- Pope, M.K. From Latin to Modern French. p. 6.

- Posner. Linguistic Change in French. 250–251

- Maria Polinsky and Ezra Van Everbroeck (June 2003). "Develop of Gender Classifications: Modeling the Historical Change from Latin to French". Language. 79 (2). pp. 365–380.

- Pope, From Latin to modern French, with especial consideration of Anglo-Norman, p. 16.

External links

- Histoire de la langue française (in French)

- The Breton Wikipedia page on the French language gives examples from various stages in the development of French.