La Spezia–Rimini Line

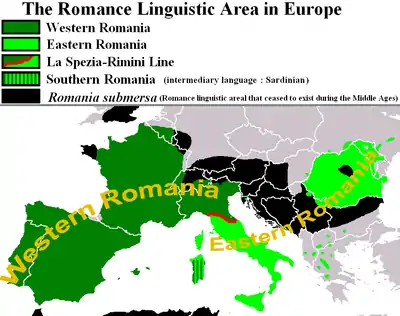

The La Spezia–Rimini Line (also known as the Massa–Senigallia Line), in the linguistics of the Romance languages, is a line that demarcates a number of important isoglosses that distinguish Romance languages south and east of the line from Romance languages north and west of it. The line runs through northern Italy, very roughly from the cities of La Spezia to Rimini. Romance languages on the eastern half of it include Italian and the Eastern Romance languages (Romanian, Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, Istro-Romanian), whereas Spanish, French, Catalan, Portuguese, Occitan as well as Gallo‒Italic languages and Romansh languages are representatives of the Western group. Sardinian does not fit into either Western or Eastern Romance.[1]

It has been suggested that the origin of these developments is to be found in the last decades of the Western Roman Empire and the Ostrogothic Kingdom (c. 395–535 AD). During this period, the area of Italy north of the line was dominated by an increasingly Germanic Roman army of (Northern) Italy, followed by the Ostrogoths; whereas the Roman Senate and Papacy became the dominant social elements south of the line. As for the provinces outside Italy, the social influences in Gaul and Iberia were broadly similar to those in Northern Italy, whereas the Balkans were dominated by the Byzantine Empire at this time (and later, by Slavic peoples).[2]

Some linguists, however, say[3] that the line actually runs through Massa and Senigallia about 40 kilometres further to the south and would more accurately be called the Massa–Senigallia Line.

In either case, it roughly coincides with the northern range of the Apennine Mountains, which could have helped the appearance of these linguistic differences.

Generally speaking, the western Romance languages show common innovations that the eastern Romance languages tend to lack. The three isoglosses considered traditionally are:

- formation of the plural form of nouns

- the voicing or not of some consonants

- Pronunciation of Latin c before e/i as /(t)s/ or /tʃ/ (ch)

To these should be added a fourth criterion, generally more decisive than the phenomenon of voicing:

- preservation (below the line) or simplification (above the line) of Latin geminate consonants

Plural of nouns

North and west of the line (excluding all Northern Italian varieties) the plural of nouns was drawn from the Latin accusative case, and is marked with /s/ regardless of grammatical gender or declension. South and east of the line, the plurals of nouns are marked by changing the final vowel, either because these were taken from the Latin nominative case, or because the original /s/ changed into a vocalic sound (see the Romance plurals origin debate). Compare the plurals of cognate nouns in Aromanian, Romanian, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, French, Sardinian and Latin:

| Eastern Romance | Western Romance | Sardinian | Latin | English | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromanian | Romanian | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Catalan | French | nominative | accusative | ||

| yeatsã yets | viață vieți | vita vite | vida vidas | vida vidas | vida vides | vie vies | bida bidas | vita vitae | vitam vitās | life lives |

| lupu lupi | lup lupi | lupo lupi | lobo lobos | lobo lobos | llop llops | loup loups | lupu lupos/-us | lupus lupī | lupum lupōs | wolf wolves |

| omu uamini | om oameni | uomo uomini | hombre hombres | homem homens | home homes/hòmens | homme hommes | ómine/-i ómines/-is | homo hominēs | hominēm hominēs | man men |

| an anji | an ani | anno anni | año años | ano anos | any anys | an ans | annu annos | annus annī | annum annōs | year years |

| steauã steali/-e | stea stele | stella stelle | estrella estrellas | estrela estrelas | estrella estrellas | étoile étoiles | istedda isteddas | stēlla stēllae | stēllam stēllās | star stars |

| tser tseri/-uri | cer ceruri | cielo cieli | cielo cielos | céu céus | cel cels | ciel cieux/ciels | chelu chelos | caelum caelī | caelum caelōs | sky skies |

Result of ci/ce palatalization

The pronunciation of Latin ci/ce, as in centum and civitas, has a divide that roughly follows the line: Italian and Romanian use /tʃ/ (as in English church), while most Western Romance languages use /(t)s/. The exceptions are some Gallo-Italic languages immediately north of the line, as well as Norman and Mozarabic.

Voicing and degemination of consonants

Another isogloss that falls on the La Spezia–Rimini Line deals with the restructured voicing of voiceless consonants, mainly Latin sounds /p/, /t/ and /k/, which occur between vowels. Thus, Latin catēna ('chain') becomes catena in Italian, but cadeia in Portuguese, cadena in Catalan and Spanish, cadéna/cadèina in Emilian, caéna/cadéna in Venetian and chaîne in French (with loss of intervocalic [ð]). Voicing, or further weakening, even to loss of these consonants is characteristic of the western branch of Romance; their retention is characteristic of eastern Romance.

However, the differentiation is not totally systematic, and there are exceptions that undermine the isogloss: Gascon dialects in south-west France and Aragonese in northern Aragon, Spain (geographically Western Romance) also retain the original Latin voiceless stop between vowels. The presence in Tuscany and elsewhere below the line of a small percentage but large number of voiced forms both in general vocabulary and in traditional toponyms also challenges its absolute integrity.

The criterion of preservation vs. simplification of Latin geminate consonants stands on firmer ground. The simplification illustrated by Spanish boca /boka/ 'mouth' vs. Tuscan bocca /bokka/, both continuations of Latin bucca, typifies all of Western Romance and is systematic for all geminates except /s/ (pronounced differently if single/double even in French), /rr/ in some locales (e.g. Spanish carro and caro are still distinct), and to some degree for earlier /ll/ and /nn/ which, while not preserved as geminates, did not generally merge with the singletons (e.g. /n/ > /n/ but /nn/ > /ɲ/ in Spanish, annus > /aɲo/ 'year'). Nevertheless, the La Spezia-Rimini line is real in this respect for most of the consonant inventory, although simplification of geminates to the east in Romania spoils the neat east-west division.

Indeed, the significance of the La Spezia–Rimini Line is often challenged by specialists within both Italian dialectology and Romance dialectology. One reason is that while it demarcates preservation (and expansion) of phonemic geminate consonants (Central and Southern Italy) from their simplification (in Northern Italy, Gaul, and Iberia), the areas affected do not correspond consistently with those defined by voicing criterion. Romanian, which on the basis of lack of voicing, i-plurals and palatalisation to /tʃ/ is classified with Central and Southern Italian, has undergone simplification of geminates, a defining characteristic of Western Romance, after the rhotacism of intervocalic /l/.

See also

- Jireček Line, the Balkans: between Latin & Greek

- Classification of Romance languages

- Romance plurals

- Plural inflection in Eastern Lombard

- Röstigraben

- Watford Gap

Notes

- Ruhlen M. (1987). A guide to the world's languages, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- Brown, Peter (1970). The World of Late Antiquity. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 131. ISBN 0-393-95803-5.

- Renzi, Lorenzo (1985). Nuova introduzione alla filologia romanza. Bologna: il Mulino. p. 176. ISBN 88-15-04340-3.

References

Note that, up to c. 1600, the word Lombard meant Cisalpine, but now it has narrowed in its meaning, referring only to the administrative region of Lombardy .

- Adolfo, Mussafia (1873) Beitrag zur Kunde der norditalienischen Mundarten im XV. Jahrhunderte. Wien.

- Beltrami, Pierluigi; Bruno Ferrari, Luciano Tibiletti, Giorgio D'Ilario (1970) Canzoniere Lombardo. Varesina Grafica Editrice.

- Brevini, Franco (1984) Lo stile lombardo : la tradizione letteraria da Bonvesin da la Riva a Franco Loi. (Lombard style: literary tradition from Bonvesin da la Riva to Franco Loi.) Pantarei, Lugan.

- Brown, Peter (1970) The World of Late Antiquity W. W. Norton New York.

- Comrie, Bernard; Stephen Matthews, Maria Polinsky, eds. (2003) The Atlas of languages : the origin and development of languages throughout the world. New York: Facts On File. p. 40.

- Cravens, Thomas D. (2002) Comparative Romance Dialectology: Italo-Romance clues to Ibero-Romance sound change. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Hull, Dr Geoffrey (1982) The linguistic unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia. PhD thesis, University of Western Sydney.

- Hull, Dr Geoffrey (1989) Polyglot Italy: Languages, Dialects, Peoples. Melbourne: CIS Educational.

- Maiden, Martin (1995) A linguistic history of Italian. London: Longman.

- Maiden, Martin & Mair Parry, eds. (1997) The Dialects of Italy. London: Routledge.

- Sanga, Glauco La lingua Lombarda, in Koiné in Italia, dalle origini al 1500. (Koinés in Italy, from the origin to 1500.) Bèrghem: Lubrina.

- Vitale, Maurizio (1983) Studi di lingua e letteratura lombarda. (Studies in Lombard language and literature.) Pisa : Giardini.

- Wurm, Stephen A. (2001) Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger of Disappearing. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, p. 29.