History of Peru

The history of Peru spans 10 millennia, extending back through several stages of cultural development in the mountain region and the lakes. Peru was home to the Norte Chico civilization, the oldest civilization in the Americas and one of the six oldest in the world, and to the Inca Empire, the largest and most advanced state in pre-Columbian America. It was conquered by the Spanish Empire in the 16th century, which established a Viceroyalty with jurisdiction over most of its South American domains. The nation declared independence from Spain in 1821, but consolidated only after the Battle of Ayacucho three years later.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Peru |

.svg.png.webp) |

| By chronology |

| By political entity |

| By topic |

|

|

Pre-Columbian cultures

Hunting tools dating back to more than 11,000 years ago have been found inside the caves of Pachacamac, Telarmachay, Junin, and Lauricocha.[1] Some of the oldest civilizations appeared circa 6000 BC in the coastal provinces of Chilca and Paracas, and in the highland province of Callejón de Huaylas. Over the next three thousand years, inhabitants switched from nomadic lifestyles to cultivating land, as evidenced from sites such as Jiskairumoko, Kotosh, and Huaca Prieta. Cultivation of plants such as corn and cotton (Gossypium barbadense) began, as well as the domestication of animals such as the wild ancestors of the llama, the alpaca and the guinea pig, as seen in the 6000 BC dated Camelid relief paintings in the Mollepunko caves in Callalli. Inhabitants practiced spinning and knitting of cotton and wool, basketry, and pottery.

As these inhabitants became sedentary, farming allowed them to build settlements. As a result, new societies emerged along the coast and in the Andean mountains. The first known city in the Americas was Caral, located in the Supe Valley 200 km north of Lima. It was built in approximately 2500 BC.[2]

The remnants of this civilization, also known as Norte Chico, consists of approximately 30 pyramidal structures built up in receding terraces ending in a flat roof; some of them measuring up to 20 meters in height. Caral was considered one of the cradles of civilization.[2]

In the early 21st century, archeologists discovered new evidence of ancient pre-Ceramic complex cultures. In 2005, Tom D. Dillehay and his team announced the discovery of three irrigation canals that were 5400 years old, and a possible fourth that was 6700 years old in the Zaña Valley in northern Peru. This was the evidence of community agricultural improvements that occurred at a much earlier date than previously believed.[3]

In 2006, Robert Benfer and a research team discovered a 4200-year-old observatory at Buena Vista, a site in the Andes several kilometers north of present-day Lima. They believe the observatory was related to the society's reliance on agriculture and understanding of the seasons. The site includes the oldest three-dimensional sculptures found thus far in South America.[4] In 2007, the archaeologist Walter Alva and his team found a 4000-year-old temple with painted murals at Ventarrón, in the northwest Lambayeque region. The temple contained ceremonial offerings gained from an exchange with Peruvian jungle societies, as well as those from the Ecuador a coast.[5] Such finds show sophisticated, monumental construction requiring large-scale organization of labor, suggesting that hierarchical complex cultures arose in South America much earlier than scholars had thought.

Many other civilizations developed and were absorbed by the most powerful ones such as Kotosh, Chavin, Paracas, Lima, Nasca, Moche, Tiwanaku, Wari, Lambayeque, Chimu and Chincha, among others. The Paracas culture emerged on the southern coast around 300 BC. They are known for their use of vicuña fibers instead of just cotton to produce fine textiles—innovations that did not reach the northern coast of Peru until centuries later. Coastal cultures such as the Moche and Nazca flourished from about 100 BC to about AD 700: the Moche produced impressive metalwork, as well as some of the finest pottery seen in the ancient world, while the Nazca are known for their textiles and the enigmatic Nazca lines.

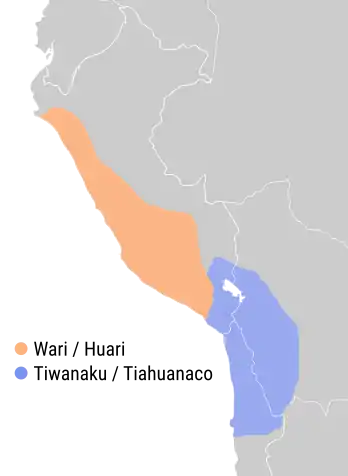

These coastal cultures eventually began to decline as a result of recurring el Niño floods and droughts. In consequence, the Huari and Tiwanaku, who dwelt inland in the Andes, became the predominant cultures of the region encompassing much of modern-day Peru and Bolivia. They were succeeded by powerful city-states such as Chancay, Sipan, and Cajamarca, and two empires: Chimor and Chachapoyas. These cultures developed relatively advanced techniques of cultivation, gold and silver craft, pottery, metallurgy, and knitting. Around 700 BC, they appear to have developed systems of social organization that were the precursors of the Inca civilization.

In the highlands, both the Tiahuanaco culture, near Lake Titicaca in both Peru and Bolivia, and the Wari culture, near the present-day city of Ayacucho, developed large urban settlements and wide-ranging state systems between 500 and 1000 AD.[6]

Not all Andean cultures were willing to offer their loyalty to the Incas as they expanded their empire because many were openly hostile. The people of the Chachapoyas culture were an example of this, but the Inca eventually conquered and integrated them into their empire.

Archaeologists led by Gabriel Prieto revealed the largest mass child sacrifice with more than 140 children skeleton and 200 Llamas dating to the Chimú culture after he was informed about some children had found bones in a dune nearby Prieto’s fieldwork in 2011.[7][8]

According to the researchers' notes in the study, there was cut marks on the sterna, or breastbones some of the children and the llamas. Children’s faces were smeared with a red pigment during the ceremony before their chests had been cut open, most likely to remove their hearts. Remains showed that these kids came from different regions and when the children and llamas were sacrificed, the area was drenched with water.[9]

“We have to remember that the Chimú had a very different world view than Westerners today. They also had very different concepts about death and the role each person plays in the cosmos, perhaps the victims went willingly as messengers to their gods, or perhaps Chimú society believed this was the only way to save more people from destruction” said anthropologists Ryan Williams. [10]

Inca Empire (1438–1532)

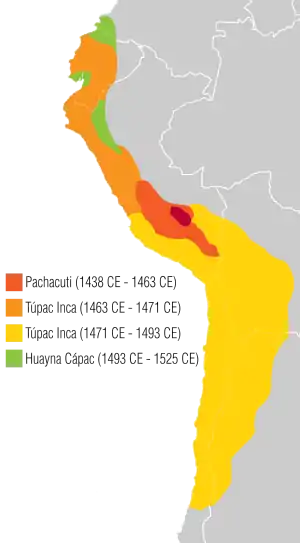

The Incas built the largest and most advanced empire and dynasty of pre-Columbian America.[11] The Tahuantinsuyo—which is derived from Quechua for "The Four United Regions"—reached its greatest extension at the beginning of the 16th century. It dominated a territory that included (from north to south): the southwest part of Ecuador, part of Colombia, the main territory of Peru, the northern part of Chile, and the northwest part of Argentina; and from east to west, from the southwest part of Bolivia to the Amazonian forests.

The empire originated from a tribe based in Cusco, which became the capital. Pachacutec wasn't the first Inca, but he was the first ruler to considerably expand the boundaries of the Cusco state. He could probably be compared to Alexander the Great (from Macedon), Julius Caesar (of the Roman Empire), Attila (from the Huns tribes) and Genghis Khan (from the Mongol Empire). His offspring later ruled an empire by both violent invasions and peaceful conquests, that is, intermarriages among the rulers of small kingdoms and the current Inca ruler.

In Cuzco, the royal city was created to resemble a cougar; the head, the main royal structure, formed what is now known as Sacsayhuamán. The empire's administrative, political, and military center was located in Cusco. The empire was divided into four quarters: Chinchaysuyu, Antisuyu, Kuntisuyu and Qullasuyu.

The official language was Quechua. It was the language of a neighbouring tribe of the original tribe of the empire. Conquered populations—tribes, kingdoms, states, and cities—were allowed to practice their own religions and lifestyles, but had to recognize Inca cultural practices as superior to their own. Inti, the sun god, was to be worshipped as one of the most important gods of the empire. His representation on earth was the Inca ("Emperor").

The Tawantinsuyu was organized in dominions with a stratified society, in which the ruler was the Inca. It was also supported by an economy based on the collective property of the land. The empire, being quite large, also had an impressive transportation system of roads to all points of the empire called the Inca Trail, and chasquis, message carriers who relayed information from anywhere in the empire to Cusco.

Machu Picchu (Quechua for "old peak"; sometimes called the "Lost City of the Incas") is a well-preserved pre-Columbian Inca ruin located on a high mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley, about 70 km (44 mi) northwest of Cusco. Elevation measurements vary depending on whether the data refers to the ruin or the extremity of the mountain; Machu Picchu tourist information reports the elevation as 2,350 m (7,711 ft)[1]. Forgotten for centuries by the outside world (although not by locals), it was brought back to international attention by Yale archaeologist Hiram Bingham III. Bingham, often cited as the inspiration for Indiana Jones, "scientifically rediscovered" the site in 1911 and brought international attention to the site with his best-selling book Lost City of the Incas. Peru is pursuing legal efforts to retrieve thousands of artifacts that Bingham removed from the site and sold to the current owners at Yale University.[12]

Although Machu Picchu is by far the most well known internationally, Peru boasts of many other sites where the modern visitor can see extensive and well-preserved ruins, remnants of the Inca-period and even older constructions. Much of the Inca architecture and stonework found at these sites continues to confound archaeologists. For example, at Sacsaywaman in Cusco, the zig-zag-shaped walls are composed of massive boulders fitted very precisely to one another's irregular, angular shapes. No mortar holds them together, but nonetheless they have remained absolutely solid through the centuries, surviving earthquakes that flattened many of the colonial constructions of Cusco. Damage to the walls visible today was mainly inflicted during battles between the Spanish and the Inca, as well as later, in the colonial era. As Cusco grew, the walls of Sacsaywaman were partially dismantled, the site becoming a convenient source of construction materials for the city's newer inhabitants. It is still not known how these stones were shaped and smoothed, lifted on top of one another (they really are very massive), or fitted together by the Incas; we also do not know how they transported the stones to the site in the first place. The stone used is not native to the area and most likely came from mountains many kilometers away.

European colonization of Peru (1532–1572)

| The etymology of Peru: The word Peru may be derived from Birú, the name of a local ruler who lived near the Bay of San Miguel, Panama, in the early 16th century.[13] When his possessions were visited by Spanish explorers in 1522, they were the southernmost part of the New World yet known to Europeans.[14] Thus, when Francisco Pizarro explored the regions farther south, they came to be designated Birú or Peru.[15]

An alternative history is provided by the contemporary writer Inca Garcilasco de la Vega, son of an Inca princess and a conquistador. He says the name Birú was that of a common Indian happened upon by the crew of a ship on an exploratory mission for governor Pedro Arias de Ávila, and goes on to relate many more instances of misunderstandings due to the lack of a common language.[16] The Spanish Crown gave the name legal status with the 1529 Capitulación de Toledo, which designated the newly encountered Inca Empire as the province of Peru.[17] Under Spanish rule, the country adopted the denomination Viceroyalty of Peru, which became Republic of Peru after independence. |

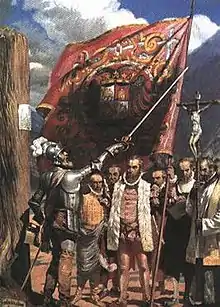

When the Spanish landed in 1531, Peru's territory was the nucleus of the highly developed Inca civilization. Centered at Cuzco, the Inca Empire extended over a vast region, stretching from southwest Ecuador to northern Chile.

Francisco Pizarro and his brothers were attracted by the news of a rich and fabulous kingdom.[18] In 1532, they arrived in the country, which they called Peru. (The forms Biru, Pirú, and Berú are also seen in early records.) According to Raúl Porras Barrenechea, Peru is not a Quechuan nor Caribbean word, but Indo-Hispanic or hybrid.

In the years between 1524 and 1526, smallpox, introduced from the conquistadors in Panama and preceding the Spanish conquerors in Peru through transmission among natives, had swept through the Inca Empire.[19] Smallpox caused the death of the Inca ruler Huayna Capac as well as most of his family including his heir, caused the fall of the Inca political structure and contributed to the civil war between the brothers Atahualpa and Huáscar.[20] Taking advantage of this, Pizarro carried out a coup d'état. On 16 November 1532, while the Atahualpa's victorious army was in an unarmed celebration in Cajamarca, the Spanish lured Atahualpa into a trap during the Battle of Cajamarca. The well-armed 168 Spaniards killed thousands of barely armed Inca soldiers and captured the newly minted Inca ruler, causing a great consternation among the natives and conditioning the future course of the fight. When Huáscar was killed, the Spanish tried and convicted Atahualpa of the murder, executing him by strangulation.

For a period, Pizarro maintained the ostensible authority of the Inca, recognizing Túpac Huallpa as the Sapa Inca after Atahualpa's death. But the conqueror's abuses made this facade too obvious. Spanish domination consolidated itself as successive indigenous rebellions were bloodily repressed. By 23 March 1534, Pizarro and the Spanish had re-founded the Inca city of Cuzco as a new Spanish colonial settlement.

Establishing a stable colonial government was delayed for some time by native revolts and bands of the Conquistadores (led by Pizarro and Diego de Almagro) fighting among themselves. A long civil war developed, from which Pizarro emerged victorious at the Battle of Las Salinas. In 1541, Pizarro was assassinated by a faction led by Diego de Almagro II (El Mozo), and the stability of the original colonial regime was shaken up in the ensuing civil war.

Despite this, the Spaniards did not neglect the colonizing process. Its most significant milestone was the foundation of Lima in January 1535, from which the political and administrative institutions were organized. The new rulers instituted an encomienda system, by which the Spanish extracted tribute from the local population, part of which was forwarded to Seville in return for converting the natives to Christianity. Title to the land itself remained with the king of Spain. As governor of Peru, Pizarro used the encomienda system to grant virtually unlimited authority over groups of native Peruvians to his soldier companions, thus forming the colonial land-tenure structure. The indigenous inhabitants of Peru were now expected to raise Old World cattle, poultry, and crops for their landlords. Resistance was punished severely, giving rise to the "Black Legend".

The necessity of consolidating Spanish royal authority over these territories led to the creation of a Real Audiencia (Royal Audience). The following year, in 1542, the Viceroyalty of Peru (Virreinato del Perú) was established, with authority over most of Spanish-ruled South America. (Colombia, Ecuador, Panamá and Venezuela were split off as the Viceroyalty of New Granada (Virreinato de Nueva Granada) in 1717; and Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay were set up as the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776).

After Pizarro's death, there were numerous internal problems, and Spain finally sent Blasco Núñez Vela to be Peru's first viceroy in 1544. He was later killed by Pizarro's brother, Gonzalo Pizarro, but a new viceroy, Pedro de la Gasca, eventually managed to restore order. He captured and executed Gonzalo Pizarro.

A census taken by the last Quipucamayoc indicated that there were 12 million inhabitants of Inca Peru; 45 years later, under viceroy Toledo, the census figures amounted to only 1,100,000 Inca. Historian David N. Cook estimates that their population decreased from an estimated 9 million in the 1520s to around 600,000 in 1620 mainly because of infectious diseases.[21] While the attrition was not an organized attempt at genocide, the results were similar. Scholars now believe that, among the various contributing factors, epidemic disease such as smallpox (unlike the Spanish, the Amerindians had no immunity to the disease)[22] was the overwhelming cause of the population decline of the American natives.[23] Inca cities were given Spanish Christian names and rebuilt as Spanish towns centered around a plaza with a church or cathedral facing an official residence. A few Inca cities like Cuzco retained native masonry for the foundations of their walls. Other Inca sites, like Huanuco Viejo, were abandoned for cities at lower altitudes more hospitable to the Spanish.

Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1824)

In 1542, the Spanish Crown created the Viceroyalty of Peru, which was reorganized after the arrival of Viceroy Francisco de Toledo in 1572. He put an end to the indigenous Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba and executed Tupac Amaru I. He also sought economic development through commercial monopoly and mineral extraction, mainly from the silver mines of Potosí. He reused the Inca mita, a forced labor program, to mobilize native communities for mining work. This organization transformed Peru into the principal source of Spanish wealth and power in South America.

The town of Lima, founded by Pizarro on 18 January 1535 as the "Ciudad de Reyes" (City of Kings), became the seat of the new viceroyalty. It grew into a powerful city, with jurisdiction over most of Spanish South America. Precious metals passed through Lima on their way to the Isthmus of Panama and from there to Seville, Spain. By the 18th century, Lima had become a distinguished and aristocratic colonial capital, seat of a university and the chief Spanish stronghold in the Americas.

Nevertheless, throughout the eighteenth century, further away from Lima in the provinces, the Spanish did not have complete control. The Spanish could not govern the provinces without the help of local elite. This local elite, who governed under the title of Curaca, took pride in their Incan history. Additionally, throughout the eighteenth century, indigenous people rebelled against the Spanish. Two of the most important rebellions were that of Juan Santos Atahualpa in 1742 in the Andean jungle provinces of Tarma and Jauja, and Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II in 1780 around the highlands near Cuzco.

At the time, an economic crisis was developing due to creation of the Viceroyalties of New Granada and Rio de la Plata (at the expense of its territory), the duty exemptions that moved the commercial center from Lima to Caracas and Buenos Aires, and the decrease of the mining and textile production. This crisis proved favorable for the indigenous rebellion of Túpac Amaru II and determined the progressive decay of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

In 1808, Napoleon invaded the Iberian Peninsula and took the king, Ferdinand VII, hostage. Later in 1812, the Cadíz Cortes, the national legislative assembly of Spain, promulgated a liberal Constitution of Cadiz. These events inspired emancipating ideas between the Spanish Criollo people throughout the Spanish America. In Peru, the Creole rebellion of Huánuco arose in 1812 and the rebellion of Cuzco arose between 1814 and 1816. Despite these rebellions, the Criollo oligarchy in Peru remained mostly Spanish loyalist, which accounts for the fact that the Viceroyalty of Peru became the last redoubt of the Spanish dominion in South America.

Wars of independence (1811–1824)

Peru's movement toward independence was launched by an uprising of Spanish-American landowners and their forces, led by José de San Martín of Argentina and Simón Bolívar of Venezuela. San Martín, who had displaced the royalists of Chile after the Battle of Chacabuco, and who had disembarked in Paracas in 1819, led the military campaign of 4,200 soldiers. The expedition, which included warships, was organized and financed by Chile which sailed from Valparaíso in August 1820.[24] San Martin proclaimed the independence of Peru in Lima on 28 July 1821, with the words "... From this moment on, Peru is free and independent, by the general will of the people and the justice of its cause that God defends. Long live the homeland! Long live freedom! Long live our independence!". San Martín received the title of "Protector of Peruvian Freedom" in August 1821 after partially liberating Peru from the Spanish.[25]:295

On 26 and 27 July 1822, Bolívar held the Guayaquil Conference with San Martín and attempted to decide the political fate of Peru. San Martín opted for a constitutional monarchy, whilst Bolivar (Head of the Northern Expedition) opted for a republican. Nonetheless, they both followed the notion that it was to be independent of Spain. Following the interview, San Martin abandoned Peru on 22 September 1822 and left the whole command of the independence movement to Simon Bolivar.

The Peruvian congress named Bolivar dictator of Peru on 10 February 1824, which allowed him to reorganize the political and military administration completely. Assisted by general Antonio José de Sucre, Bolívar decisively defeated the Spanish cavalry at the Battle of Junín on 6 August 1824. Sucre destroyed the still numerically superior remnants of the Spanish forces at Ayacucho on 9 December 1824. The war would not end until the last royalist holdouts surrendered the Real Felipe Fortress in 1826.

The victory brought about political independence, but there remained indigenous and mestizo supporters of the monarchy and in Huanta Province, they rebelled in 1825–28, which is known as the war of the punas or the Huanta Rebellion.[26][27]

Spain made futile attempts to regain its former colonies, such as the Battle of Callao (1866), and only in 1879 finally recognized Peruvian independence.

Republic of Peru

Territorial disputes (1824–1884)

After independence, Peru and its neighbors engaged in intermittent territorial disputes. An attempt to unite Peru and Bolivia was made during the period 1836–1839 by Bolivian President Andres de Santa Cruz when the Peru-Bolivian Confederation came into existence. Severe internal opposition led to its demise in the War of the Confederation which dovetailed into a Peruvian attempt to annex Bolivia by Agustín Gamarra that ultimately failed and turned into a protracted war.[28] Between 1857 and 1860 a war broke out against Ecuador for the disputed territories in the Amazon. The Peruvian victory in the war prevented the Ecuadorian claims to settle in the area.[29]

Peru embarked on a railroad-building program. The American entrepreneur Henry Meiggs built a standard gauge line from Callao across the Andes to the interior, Huancayo; he built the line and controlled its politics for a while; in the end, he bankrupted himself and the country. President Tomás Guardia contracted with Meiggs in 1871 to build a railroad to the Atlantic. Financial problems forced the government to take over in 1874. The labor conditions were complex, with conflicts arising from different levels of skill and organization among the North Americans, Europeans, Blacks, and the Chinese. Conditions were very brutal for the Chinese, and led to strikes and violent suppression.[30]

.png.webp)

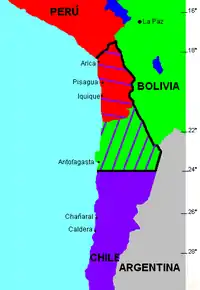

In 1879, Peru entered the War of the Pacific which lasted until 1884. Bolivia invoked its alliance with Peru against Chile. The Peruvian Government tried to mediate the dispute by sending a diplomatic team to negotiate with the Chilean government, but the committee concluded that war was inevitable. On 14 March 1879, Bolivia declared war and Chile, in response, declared war on Bolivia and Peru on 5 April 1879 with Peru following with its own declaration of war the next day. Almost five years of war ended with the loss of the department of Tarapacá and the provinces of Tacna and Arica, in the Atacama region.

Originally, Chile committed to a referendum for the cities of Arica and Tacna to be held years later, in order to determine their national affiliation. However, Chile refused to apply the treaty, and both countries could not determine the statutory framework. In an arbitrage that both countries admitted, the United States decided that the plebiscite was impossible to take, therefore, direct negotiations between the parties led to a treaty (Treaty of Lima, 1929), in which Arica was ceded to Chile and Tacna remained in Peru. Tacna was returned to Peru on 29 August 1929. The territorial loss and the extensive looting of Peruvian cities by Chilean troops left scars on the country's relations with Chile that have not yet fully healed.

Following the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War of 1941, the Rio Protocol sought to formalize the boundary between those two countries. Ongoing boundary disagreements led to a brief war in early 1981 and the Cenepa War in early 1995, but in 1998, the governments of both countries signed an historic peace treaty that clearly demarcated the international boundary between them. In late 1999, the governments of Peru and Chile implemented the last outstanding article of their 1929 border agreement.

Aristocratic Republic (1884–1930)

After the War of the Pacific, an extraordinary effort of rebuilding began. The government started to initiate a number of social and economic reforms in order to recover from the damage of the war. Political stability was achieved only in the early 1900s.

In 1894, Nicolás de Piérola, after allying his party with the Civil Party of Peru to organize guerrilla fighters to occupy Lima, ousted Andrés Avelino Cáceres and once again became president of Peru in 1895. After a brief period in which the military once again controlled the country, civilian rule was permanently established with Pierola's election in 1895. His second term was successfully completed in 1899 and was marked by his reconstruction of a devastated Peru by initiating fiscal, military, religious, and civil reforms. Until the 1920s, this period was called the "Aristocratic Republic", since most of the presidents that ruled the country were from the social elite.

During Augusto B. Leguía's periods in government (1908–1912 and 1919–1930), the latter known as the "Oncenio" (the "Eleventh"), the entrance of American capital became general and the bourgeoisie was favored. This policy, along with increased dependence on foreign investment, focused opposition from the most progressive sectors of Peruvian society against the landowner oligarchy.

There was a final peace treaty in 1929, signed between Peru and Chile and called the Treaty of Lima by which Tacna returned to Peru and Peru yielded permanently the formerly rich provinces of Arica and Tarapacá, but kept certain rights to the port activities in Arica and restrictions on what Chile can do on those territories.

In 1924, from Mexico, university reform leaders in Peru who had been forced into exile by the government founded the American People's Revolutionary Alliance (ARPA), which had a major influence on the country's political life. APRA is largely a political expression of the university reform and workers' struggles of the years 1918–1920. The movement draws its influences from the Mexican revolution and its 1917 Constitution, particularly on issues of agrarianism and indigenism, and to a lesser extent from the Russian revolution. Close to Marxism (its leader, Haya de la Torre, declares that "APRA is the Marxist interpretation of the American reality"), it nevertheless moves away from it on the question of class struggle and on the importance given to the struggle for the political unity of Latin America.[31]

In 1928, the Peruvian Socialist Party was founded, notably under the leadership of José Carlos Mariátegui, himself a former member of APRA. Shortly afterwards, in 1929, the party created the General Confederation of Workers.

Alternation between democracy and militarism (1930–1979)

After the worldwide crisis of 1929, numerous brief governments followed one another. The APRA party had the opportunity to cause system reforms by means of political actions, but it was not successful. This was a nationalistic movement, populist and anti-imperialist, headed by Victor Raul Haya de la Torre in 1924. The Socialist Party of Peru, later the Peruvian Communist Party, was created four years later and it was led by Jose C. Mariategui.

Repression was brutal in the early 1930s and tens of thousands of APRA followers (Apristas) were executed or imprisoned. This period was also characterized by a sudden population growth and an increase in urbanization. According to Alberto Flores Galindo, "By the 1940 census, the last that utilized racial categories, mestizos were grouped with whites, and the two constituted more than 53 percent of the population. Mestizos likely outnumbered the indigenous peoples and were the largest population group."[32] On 12 February 1944, Peru was one of the South American nations – following Brazil on 22 August 1942, Bolivia on 7 April 1943 and Colombia on 26 July 1943 to align with the Allied forces against the Axis.

Following the Allied victory in World War II by 2 September 1945, Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (founder of the APRA), together with José Carlos Mariátegui (leader of the Peruvian Communist Party), were two major forces in Peruvian politics. Ideologically opposed, they both managed to create the first political parties that tackled the social and economic problems of the country. Although Mariátegui died at a young age, Haya de la Torre was twice elected president, but prevented by the military from taking office. During World War II, the country rounded up around 2,000 of its Japanese immigrant population and shipped them to the United States as part of the Japanese-American internment program.[33]

President Bustamante y Rivero hoped to create a more democratic government by limiting the power of the military and the oligarchy. Elected with the cooperation of the APRA, conflict soon arose between the President and Haya de la Torre. Without the support of the APRA party, Bustamante y Rivero found his presidency severely limited. The President disbanded his Aprista cabinet and replaced it with a mostly military one. In 1948, Minister Manuel A. Odria and other right-wing elements of the Cabinet urged Bustamante y Rivero to ban the APRA, but when the President refused, Odría resigned his post.

In a military coup on 29 October, Gen. Manuel A. Odria became the new President. Odría's presidency was known as the Ochenio. He came down hard on APRA, momentarily pleasing the oligarchy and all others on the right, but followed a populist course that won him great favor with the poor and lower classes. A thriving economy allowed him to indulge in expensive but crowd-pleasing social policies. At the same time, however, civil rights were severely restricted and corruption was rampant throughout his régime.

It was feared that his dictatorship would run indefinitely, so it came as a surprise when Odría allowed new elections. During this time, Fernando Belaúnde Terry started his political career, and led the slate submitted by the National Front of Democratic Youth. After the National Election Board refused to accept his candidacy, he led a massive protest, and the striking image of Belaúnde walking with the flag was featured by news magazine Caretas the following day, in an article entitled "Así Nacen Los Lideres" ("Thus Are Leaders Born"). Belaúnde's 1956 candidacy was ultimately unsuccessful, as the dictatorship-favored right-wing candidacy of Manuel Prado Ugarteche took first place.

Belaúnde ran for president once again in the national elections of 1962; this time with his own party, Acción Popular (Popular Action). The results were very tight; he ended in second place, following Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (APRA), by less than 14,000 votes. Since none of the candidates managed to get the constitutionally established minimum of one third of the vote required to win outright, selection of the President should have fallen to Congress; the long-held antagonistic relationship between the military and APRA prompted Haya de la Torre to make a deal with former dictator Odria, who had come in third, which would have resulted in Odria taking the Presidency in a coalition government.

However, widespread allegations of fraud prompted the Peruvian military to depose Prado and install a military junta, led by Ricardo Perez Godoy. Godoy ran a short transitional government and held new elections in 1963, which were won by Belaúnde by a more comfortable but still narrow five percent margin.

Throughout Latin America in the 1960s, communist movements inspired by the Cuban Revolution sought to win power through guerrilla warfare. The Revolutionary Left Movement (Peru), or MIR, launched an insurrection that had been crushed by 1965, but Peru's internal strife would only accelerate until its climax in the 1990s.

The military has been prominent in Peruvian history. Coups have repeatedly interrupted civilian constitutional government. The most recent period of military rule (1968–1980) began when General Juan Velasco Alvarado overthrew elected President Fernando Belaúnde Terry of the Popular Action Party (AP). As part of what has been called the "first phase" of the military government's nationalist program, Velasco undertook an extensive agrarian reform program and nationalized the fish meal industry, some petroleum companies, and several banks and mining firms.

General Francisco Morales Bermúdez replaced Velasco in 1975, citing Velasco's economic mismanagement and deteriorating health. Morales Bermúdez moved the revolution into a more conservative "second phase", tempering the radical measures of the first phase and beginning the task of restoring the country's economy. A constitutional assembly was created in 1979, which was led by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre. Morales Bermúdez presided over the return to civilian government in accordance with a new constitution drawn up in 1979.

1980s

During the 1980s, cultivation of illicit coca was established in large areas on the eastern Andean slope. Rural insurgent movements, like the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso, SL) and the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) increased and derived significant financial support from alliances with the narcotics traffickers, leading to the Internal conflict in Peru.

In the May 1980 elections, President Fernando Belaúnde Terry was returned to office by a strong plurality. One of his first actions as President was the return of several newspapers to their respective owners. In this way, freedom of speech once again played an important part in Peruvian politics. Gradually, he also attempted to undo some of the most radical effects of the Agrarian Reform initiated by Velasco and reversed the independent stance that the military government of Velasco had with the United States.

Belaúnde's second term was also marked by the unconditional support for Argentine forces during the Falklands War with the United Kingdom in 1982. Belaúnde declared that "Peru was ready to support Argentina with all the resources it needed". This included a number of fighter planes and possibly personnel from the Peruvian Air Force, as well as ships, and medical teams. Belaunde's government proposed a peace settlement between the two countries, but it was rejected by both sides, as both claimed undiluted sovereignty of the territory. In response to Chile's support of the UK, Belaúnde called for Latin American unity.

The nagging economic problems left over from the previous military government persisted, worsened by an occurrence of the "El Niño" weather phenomenon in 1982–83, which caused widespread flooding in some parts of the country, severe droughts in others, and decimated the schools of ocean fish that are one of the country's major resources. After a promising beginning, Belaúnde's popularity eroded under the stress of inflation, economic hardship, and terrorism.

In 1985, the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) won the presidential election, bringing Alan García to office. The transfer of the presidency from Belaúnde to García on 28 July 1985 was Peru's first exchange of power from one democratically elected leader to another for the first time in 40 years.

With a parliamentary majority for the first time in APRA's history, Alan García started his administration with hopes for a better future. However, economic mismanagement led to hyperinflation from 1988 to 1990. García's term in office was marked by bouts of hyperinflation, which reached 7,649% in 1990 and had a cumulative total of 2,200,200% between July 1985 and July 1990, thereby profoundly destabilizing the Peruvian economy.

Owing to such chronic inflation, the Peruvian currency, the sol, was replaced by the Inti in mid-1985, which itself was replaced by the nuevo sol ("new sun") in July 1991, at which time the new sol had a cumulative value of one billion old soles. During his administration, the per capita annual income of Peruvians fell to $720 (below the level of 1960) and Peru's Gross Domestic Product dropped 20%. By the end of his term, national reserves were a negative $900 million.

The economic turbulence of the time exacerbated social tensions in Peru and partly contributed to the rise of the violent rebel movement Shining Path. The García administration unsuccessfully sought a military solution to the growing terrorism, committing human rights violations which are still under investigation.

In June 1979, demonstrations for free education were severely repressed by the army: 18 people were killed according to official figures, but non-governmental estimates suggest several dozen deaths. This event led to a radicalization of political protests in the countryside and ultimately led to the outbreak of the Shining Path's armed and terrorist actions.[34][35]

Fujimori's presidency and the Fujishock (1990–2000)

Concerned about the economy, the increasing terrorist threat from Sendero Luminoso and MRTA, and allegations of official corruption, voters chose a relatively unknown mathematician-turned-politician, Alberto Fujimori, as president in 1990. The first round of the election was won by well-known writer Mario Vargas Llosa, a conservative candidate who went on to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010, but Fujimori defeated him in the second round. Fujimori implemented drastic measures that caused inflation to drop from 7,650% in 1990 to 139% in 1991. The currency is devalued by 200%, prices are rising sharply (especially gasoline, whose price is multiplied by 30), hundreds of public companies are privatized and 300,000 jobs are being lost. The majority of the population had not benefited from the years of strong growth, which will ultimately only widen the gap between rich and poor. The poverty rate remained at around 50%.[36]

As other dictators did, Fujimori dissolved Congress in the auto-golpe of 5 April 1992, in order to have total control of the government of Peru. He then eliminated the constitution; called new congressional elections; and implemented substantial economic reform, including privatization of numerous state-owned companies, creation of an investment-friendly climate, and sound management of the economy.

Fujimori's administration was dogged by several insurgent groups, most notably Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), which carried on a terrorist campaign in the countryside throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He cracked down on the insurgents and was successful in largely quelling them by the late 1990s, but the fight was marred by atrocities committed by both the Peruvian security forces and the insurgents: the Barrios Altos massacre and La Cantuta massacre by government paramilitary groups, and the bombings of Tarata and Frecuencia Latina by Shining Path. Those examples subsequently came to be seen as symbols of the human rights violations committed during the last years of violence. With the capture of Abimael Guzmán (known as President Gonzalo to the Shining Path) in September 1992, the Shining Path received a severe blow which practically destroyed the organization.

In December 1996, a group of insurgents belonging to the MRTA took over the Japanese embassy in Lima, taking 72 people hostage. Military commandos stormed the embassy compound in May 1997, which resulted in the death of all 15 hostage takers, one hostage, and 2 commandos. It later emerged, however, that Fujimori's security chief Vladimiro Montesinos may have ordered the killing of at least eight of the rebels after they surrendered.

Fujimori's constitutionally questionable decision to seek a third term and subsequent tainted victory in June 2000 brought political and economic turmoil. A bribery scandal that broke just weeks after he took office in July forced Fujimori to call new elections in which he would not run. The scandal involved Vladimiro Montesinos, who was shown in a video broadcast on TV bribing a politician to change sides. Montesinos subsequently emerged as the center a vast web of illegal activities, including embezzlement, graft, drug trafficking, as well as human rights violations committed during the war against Sendero Luminoso.

Toledo, García, Humala, Kuczynski presidencies (2001–today)

In November 2000, Fujimori resigned from office and went to Japan in self-imposed exile, avoiding prosecution for human rights violations and corruption charges by the new Peruvian authorities. His main intelligence chief, Vladimiro Montesinos, fled Peru shortly afterwards. Authorities in Venezuela arrested him in Caracas in June 2001 and turned him over to Peruvian authorities; he is now imprisoned and charged with acts of corruption and human rights violations committed during Fujimori's administration.

A caretaker government presided over by Valentín Paniagua took on the responsibility of conducting new presidential and congressional elections. The elections were held in April 2001; observers considered them to be free and fair. Alejandro Toledo (who led the opposition against Fujimori) defeated former President Alan García.

The newly elected government took office on 28 July 2001. The Toledo Administration managed to restore some degree of democracy to Peru following the authoritarianism and corruption that plagued both the Fujimori and García governments. Innocents wrongfully tried by military courts during the war against terrorism (1980–2000) were allowed to receive new trials in civilian courts.

On 28 August 2003, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), which had been charged with studying the roots of the violence of the 1980–2000 period, presented its formal report to the President.

President Toledo was forced to make a number of cabinet changes, mostly in response to personal scandals. Toledo's governing coalition had a minority of seats in Congress and had to negotiate on an ad hoc basis with other parties to form majorities on legislative proposals. Toledo's popularity in the polls suffered throughout the last years of his regime, due in part to family scandals and in part to dissatisfaction among workers with their share of benefits from Peru's macroeconomic success. After strikes by teachers and agricultural producers led to nationwide road blockages in May 2003, Toledo declared a state of emergency that suspended some civil liberties and gave the military power to enforce order in 12 regions. The state of emergency was later reduced to only the few areas where the Shining Path was operating.

On 28 July 2006, former president Alan García became the President of Peru. He won the 2006 elections after winning in a runoff against Ollanta Humala. In May 2008, President García was a signatory to The UNASUR Constitutive Treaty of the Union of South American Nations. Peru has ratified the treaty.

On 5 June 2011, Ollanta Humala was elected President in a run-off against Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of Alberto Fujimori and former First Lady of Peru, in the 2011 elections, making him the first leftist president of Peru since Juan Velasco Alvarado. In December 2011, a state of emergency was declared following popular opposition to some major mining project and environmental concerns.[37]

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski was elected president in the general election in July 2016. His parents were European refugees fleeing from Nazism. Kuczynski is committed to integrating and acknowledging Peru's indigenous populations, and state-run TV has begun daily news broadcasts in Quechua and Aymara.[38] Kuczynski was widely criticized on pardoning former President Alberto Fujimori, going against his campaign promises against his rival, Keiko Fujimori.

In March 2018, after a failure to impeach the president, Kuczynski faced yet again the threat of impeachment on the basis of corruption in vote buying and bribery with the Odebrecht corporation. On 23 March 2018, Kucyznski was forced to resign from the presidency, and has not been heard from since. His successor would be his first vice president, engineer Martín Vizcarra, who would succeed him as President until the end of the term in 2021. Vizcarra has announced publicly that he has no plans in seeking for re-election amidst the political crisis and instability.

See also

Further reading

- Dobyns, Henry F. and Paul L. Doughty, Peru: A cultural history. New York : Oxford University Press, 1976.

- Higgins, James. A history of Peruvian literature (Francis Cairns, 1987)

- Werlich, David P. Peru: a short history (Southern Illinois Univ Pr, 1978)

Conquest

- Cieza de León, Pedro de. The Discovery and Conquest of Peru: Chronicles of the New World Encounter. Ed. and trans., Alexandra Parma Cook and David Noble Cook. Durham: Duke University Press 1998.

- Hemming, John. The Conquest of the Incas. New York: Harcourt Brace Janovich, 1970.

- Lockhart, James. The Men of Cajamarca; a social and biographical study of the first conquerors of Peru, Austin, Published for the Institute of Latin American Studies by the University of Texas Press [1972]

- Yupanqui, Titu Cusi. An Inca Account of the Conquest of Peru. Trans. Ralph Bauer. Boulder: University Press of Colorado 2005.

Colonial era

- Andrien, Kenneth J. Crisis and Decline: The Viceroyalty of Peru in the Seventeenth Century. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1985.

- Andrien, Kenneth J. Andean Worlds: Indigenous History, Culture, and Consciousness under Spanish Rule, 1532–1825. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2001.

- Bakewell, Peter J. Silver and Entrepreneurship in Seventeenth-Century Potosí: The Life and times of Antonio López de Quiroga. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1988.

- Baker, Geoffrey. Imposing Harmony: Music and Society in Colonial Cuzco. Durham: Duke University Press 2008.

- Bowser, Frederick P. The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524–1650. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1973.

- Bradley, Peter T. Society, Economy, and Defence in Seventeenth-Century Peru: The Administration of the Count of Alba de Liste (1655–61). Liverpool: Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Liverpool 1992.

- Bradley, Peter T. The Lure of Peru: Maritime Intrusion into the South Sea, 1598–1701. New York: St Martin's Press 1989.

- Burns, Kathryn. Colonial Habits: Convents and the Spiritual Economy of Cuzco, Peru (1999), on the crucial role that convents played in the Andean economy as lenders and landlords; nuns exercised economic & spiritual power.

- Cahill, David. From Rebellion to Independence in the Andes: Soundings from Southern Peru, 1750–1830. Amsterdam: Aksant 2002.

- Chambers, Sarah C. From Subjects to Citizens: Honor, Gender, and Politics in Arequipa, Peru, 1780–1854. University Park: Penn State Press 1999.

- Charnay, Paul. Indian Society in the Valley of Lima, Peru, 1532–1824. Blue Ridge Summit: University Press of America 2001.

- Dean, Carolyn. Inka Bodies and the Body of Christ: Corpus Christi in Colonial Cuzco, Peru. Durham: Duke University Press 1999.

- Fisher, John. Bourbon Peru, 1750–1824. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press 2003.

- Fisher, John R., Allan J. Kuethe, and Anthony McFarlane, eds. Reform and Insurrection in Bourbon New Granada and Peru. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press 2003.

- Garrett, David T. Shadows of Empire: The Indian Nobility of Cusco, 1750–1825. New York: Cambridge University Press 2005.

- Griffiths, Nicholas. The Cross and the Serpent: Religious Repression and Resurgence in Colonial Peru. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1996.

- Hyland, Sabine. The Jesuit and the Incas: The Extraordinary Life of Padre Blas Valera, S.J. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press 2003.

- Jacobsen, Nils. Mirages of Transition: The Peruvian Altiplano, 1780–1930 (1996)

- Lamana, Gonzalo. Domination Without Dominance: Inca-Spanish Relations in Early Colonial Peru. Durham: Duke University Press 2008.

- Lockhart, James. Spanish Peru, 1532–1560: A Social History (1968), a detailed portrait of the social and economic lives of the first generation of Spanish settlers in Peru & the development of Spanish colonial society in the generation after conquest

- MacCormack, Sabine. Religion in the Andes: Vision and Imagination in Colonial Peru. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1991.

- Mangan, Jane E. Trading Roles: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Urban Economy in Colonial Potosí. Durham: Duke University Press 2005.

- Marks, Patricia. Deconstructing Legitimacy: Viceroys, Merchants, and the Military in Late Colonial Peru. University Park: Penn State Press 2007.

- Means, Philip Ainsworth. Fall of the Inca Empire and the Spanish Rule in Peru: 1530–1780 (1933)

- Miller, Robert Ryal, ed. Chronicle of Colonial Lima: The Diary of Joseph and Francisco Mugaburu, 1640–1697. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1975.

- Mills, Kenneth. Idolatry and Its Enemies: Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation, 1640–1750. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1997.

- Osorio, Alejandra B. Inventing Lima: Baroque Modernity in Peru's South Sea Metropolis. New York: Palgrave 2008.

- Poma de Ayala, Felipe Guaman, The First New Chronicle and Good Government: On the History of the World and the Incas up to 1615. Ed. and trans. Roland Hamilton. Austin: University of Texas Press 2009.

- Porras Barrenechea, Raúl (2016). El nombre del Perú (The Name of Peru). Lima: Lápix editores. ISBN 9786124722110.

- Premo, Bianca. Children of the Father King: Youth, Authority, and Legal Minority in Colonial Lima. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 2005.

- Ramírez, Susan Elizabeth. The World Turned Upside Down: Cross-Cultural Contact and Conflict in Sixteenth-Century Peru. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1996.

- Serulnikov, Sergio. Subverting Colonial Authority: Challenges to Spanish Rule in Eighteenth-Century Southern Andes. Durham: Duke University Press 2003.

- Spalding, Karen. Huarochirí: An Andean Society Under Inca and Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1984.

- Stavig, Ward. The World of Tupac Amaru: Conflict, Community, and Identity in Colonial Peru (1999), an ethnohistory that examines the lives of Andean Indians, including diet, marriage customs, labor classifications, taxation, and the administration of justice, in the eighteenth century.

- Tandeter, Enrique. Coercion and Market: Silver Mining in Colonial Potosí, 1692–1826. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1993.

- TePaske, John J., ed. and trans. Discourse and Political Reflections on the Kingdom of Peru by Jorge Juan and Antonio Ulloa. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1978.

- Thomson, Sinclair. We Alone Will Rule: Native Andean Politics in the Age of Insurgency. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 2003.

- Van Deusen, Nancy E. Between the Sacred and the Worldly: the Institutional and Cultural Practice of Recogimiento in Colonial Lima. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2001.

- Varón Gabai, Rafael. Francisco Pizarro and His Brothers: The Illusion of Power in Sixteenth-Century Peru. Trans. by Javier Flores Espinosa. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1997.

- Walker, Charles F. Shaky Colonialism: The 1746 Earthquake-Tsunami in Lima, Peru, and Its Long AftermathStay (2008)

- Wightman, Ann M. Indigenous Migration and Social Change: The Forasteros of Cuzco, 1570–1720. Durham: Duke University Press 1990.

Post Independence era

- Blanchard, Peter. Slavery and Abolition in Early Republican Peru. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources 1992.

- Bonilla, Heraclio. "The War of the Pacific and the national and colonial problem in Peru". Past & Present 81#.1 (1978): 92–118.

- Cueto, Marcos. The return of epidemics: health and society in Peru during the twentieth century (Ashgate, 2001)

- Hünefeldt, Christine. Paying the Price of Freedom: Family and Labor Among Lima's Slaves, 1800–1854. trans. by Alexandra Minna Stern. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1994.

- Kenney, Charles Dennison. Fujimori's coup and the breakdown of democracy in Latin America (Univ of Notre Dame Press, 2004)

- Larson, Brooke. Trials of Nation Making: Liberalism, Race, and Ethnicity in the Andes, 1810–1910. New York: Cambridge University Press 2004.

- Méndez G., Cecilia. The plebeian republic : the Huanta rebellion and the making of the Peruvian state, 1820–1850. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

- Miller, Rory. Region and Class in Modern Peruvian History (1987)

- Pike, Frederick B. The Modern History of Peru (1967)

- Starn, Orin. "Maoism in the Andes: The Communist Party of Peru-Shining Path and the refusal of history". Journal of Latin American Studies 27#2 (1995): 399–421.

- Walker, Charles F. Smoldering Ashes: Cuzco and the Creation of Republican Peru, 1780–1840. Durham: Duke University Press 1999.

Economic and labor history

- De Secada, C. Alexander G. "Arms, guano, and shipping: the WR Grace interests in Peru, 1865–1885". Business History Review 59#4 (1985): 597–621.

- Drake, Paul. "International Crises and Popular Movements in Latin America: Chile and Peru from the Great Depression to the Cold War", in Latin America in the 1940s, David Rock, ed. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1994, 109–140.

- Gootenberg, Paul, Between silver and guano: commercial policy and the state in postindependence Peru. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Gootenberg, Paul, Andean cocaine: the making of a global drug. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

- Greenhill, Robert G., and Rory M. Miller. "The Peruvian Government and the nitrate trade, 1873–1879". Journal of Latin American Studies 5#1 (1973): 107–131.

- Keith, Robert G. Conquest and Agrarian Change: The Emergence of the Hacienda System on the Peruvian Coast (1979)

- Peloso, Vincent C. Peasants on Plantations: Subaltern Strategies of Labor and Resistance in the Pisco Valley, Peru (Duke University Press, 1999)

- Purser, Michael, and W. F. C. Purser. Metal-mining in Peru, past and present (1971)

- Quiroz, Alfonso W. Domestic and foreign finance in modern Peru, 1850–1950: financing visions of development (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993)

- Stewart, Watt. Henry Meiggs: Yankee Pizarro (Duke University Press, 1946), on 1870s

Primary sources

Historiography

- Bonilla, Heraclio. "The New Profile of Peruvian History", Latin American Research Review Vol. 16, No. 3 (1981), pp. 210–224 in JSTOR

- Fryer, Darcy R. "A Taste of Spanish America: Reading Suggestions for Teachers of Colonial North America", Common-Place 15#2 (2015)* Heilman, Jaymie Patricia. "From the Inca to the Bourbons: New writings on pre-colonial and colonial Peru", Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History Volume 12, Number 3, Winter 2011 doi:10.1353/cch.2011.0030

- Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (Oxford University Press, 2003)

- Thurner, Mark. History's Peru: The Poetics of Colonial and Postcolonial Historiography (University Press of Florida; 2010) 302 pages; a study of Peruvian historiography from Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1539–1616) to Jorge Basadre (1903–80). full text online

External links

- Machu Picchu information, photos, maps and more

- U.S. State Department Background Note: Peru

- WorldStatesmen

- State of Fear is a documentary that tells the story of Peru's war on terror based on the findings of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

- "An Account of a Voyage up the River de la Plata, and Thence over Land to Peru: With Observations on the Inhabitants, as Well as Indians and Spaniards, the Cities, Commerce, Fertility, and Riches of That Part of America" from 1698

References

- the were, Lexus Origen de las puta Civilizaciones Andinas. p. 41.

- Charles C. Mann, "Oldest Civilization in the Americas Revealed", Science, 7 January 2005, accessed 1 Nov 2010. Quote: "Almost 5,000 years ago, ancient Peruvians built monumental temples and pyramids in dry valleys near the coast, showing that urban society in the Americas is as old as the most ancient civilizations of the Old World."

- Nicholas Bakalar, "Ancient Canals in Andes Reveal Early Agriculture", National Geographic News, 5 Dec 2005, accessed 1 Nov 2010

- Richard A. Lovett, "Oldest Observatory in Americas Discovered in Peru", National Geographic News, 16 May 2006, accessed 1 Nov 2010

- Science, American Association for the Advancement of (2007-11-23). "Oldest Mural Found in Peru". Science. 318 (5854): 1221. doi:10.1126/science.318.5854.1221d. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 220089277.

- Peru Pre-Inca Cultures. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- "Exclusive: Ancient Mass Child Sacrifice May Be World's Largest". National Geographic News. 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- EST, Hannah Osborne On 3/6/19 at 2:00 PM (2019-03-06). "World's biggest mass child sacrifice discovered in Peru, with 140 killed in "heart removal" ritual". Newsweek. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- "World's Biggest Mass Child Sacrifice Discovered In Peru, with 140 Killed in 'Heart Removal' Ritual | ARCHAEOLOGY WORLD". Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- March 2019, Laura Geggel 06. "Hearts Ripped from 140 Children and 200 Llamas in Largest Child Sacrifice in Ancient World". livescience.com. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- "The Inca". Allempires.com. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- Lubow, Arthur (June 24, 2007). "The Possessed". New York Times. p. 10. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- Porras Barrenechea (1968) p. 83

- Porras Barrenechea (1968) p. 84

- Porras Barrenechea (1968) p. 86.

- Vega, Garcilasco, Commentarios Reales de los Incas, Editoriial Mantaro, Lima, ed. 1998. pp.14–15. First published in Lisbon in 1609.

- Porras Barrenechea (1968) p. 87

- Atahualpa, Pizarro and the Fall of the Inca Empire Archived December 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 152. ISBN 0-8263-2871-7.

- Hemming, John. The Conquest of the Inca. New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1970, 28–29.

- Noble David Cook, Demographic collapse: Indian Peru, 1520–1620, p. 114.

- "The Story Of... Smallpox – and other Deadly Eurasian Germs". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- "Smallpox: Eradicating the Scourge". Bbc.co.uk. 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- Simon Collier; William F. Sater (1996). A History of Chile, 1808–1994. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-521-56827-2.

- Arana, M., 2013, Bolivar, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4391-1019-5

- Ceclia Méndez, The Plebeian Republic: The Huanta Rebellion and the Making of the Peruvian State, 1820–1850. Durham: Duke University Press 2005.

- Patrick Husson, De la Guerra a la Rebelión (Huanta Siglo XIX). Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas 1992.

- Werlich, David P. (1978). Peru — a short history. Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 70–72. ISBN 0-8093-0830-4.

- "Guerra peruano - ecuatoriana 1858 - 1860" (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- Watt Stewart, Henry Meiggs: Yankee Pizarro (1946)

- Latin America in the 20th century: 1889–1929, 1991, p. 314-319

- Galindo, Alberto Flores (2010). In Search of an Inca: Identity and Utopia in the Andes. Cambridge University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-521-59861-3.

- Agence France-Presse/Jiji Press, "Peru sorry for World War II internments", Japan Times, 16 June 2011, p. 2.

- Luis Rossell, Rupay: historias gráficas de la violencia en el Perú, 1980–1984, 2008

- Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History (2019) pp 306–346.

- The currency is devalued by 200%, prices are rising sharply (especially gasoline, whose price is multiplied by 30), hundreds of public companies are privatized and 300,000 jobs are being lost. However, the social balance sheet remains much less positive. The majority of the population has not benefited from the years of strong growth, which will ultimately only widen the gap between rich and poor. The poverty rate remained at around 50%, a level comparable to Alan Garcia's completion rate5.

- "Peru government declares state of emergency in four Cajamarca provinces". Archived from the original on 2012-06-16. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Peru's indigenous-language push".

- (in Spanish)"Historia del Peru". Lexus Editores, Barcelona 2000

_01.jpg.webp)