History of the North Sea

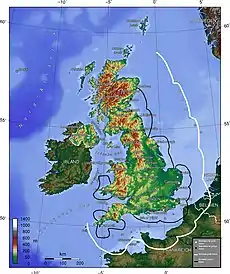

The North Sea has an extensive history of maritime commerce, resource extraction, and warfare between among the people and nations on its coasts.

Archaeological evidence shows the migration of people and technology between continental Europe, Britain, and Scandinavia throughout prehistory. The earliest records of Roman explorations of the sea begin in 12 BC. Southern Britain was formally invaded in 43 AD and gradually assimilated into the Roman Empire, leading to sustained trade across the North Sea and the English Channel. The Germanic Angles, Saxons, and Jutes from Frisia and Jutland began the next great migration across the North Sea during the Migration Period, conquering, displacing, and mixing with the native Celtic population in Britain. The Viking Age began in 793 and for the next two centuries saw significant cultural and economic exchange between Scandinavia and Europe as the Vikings used the North Sea as a jumping off point for raids, invasions, and colonization of Britain, France, Iberia, the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic.

From the Middle Ages until the end of the 15th century, before the development of good roads, maritime trade on the North Sea connected the economies of northern Europe, Britain, and Scandinavia with each other as well as with the Baltic and the Mediterranean. The Hanseatic League, a confederation of merchant guilds and market towns, dominated sea trade in the North Sea and Baltic, establishing outposts in all major ports and stimulated the growth of maritime trade in Northern Europe.[1]

By the 16th century, states were beginning to overshadown the less formal reach of the Hanseatic League in power and importance, with the Dutch Republic the first to exploit overseas colonies, a vast merchant marine, and a powerful navy to rise to prominence on the North Sea coase. Conflict with a growing England, which saw its future in maritime trade, was at the root of the first three Anglo-Dutch Wars between 1652 and 1673 each of which saw significant naval action in the North Sea. Scotland emerged as a prominent economic and cultural power during the Scottish Enlightenment of the 18th century. Militarily, the wars of the 18th and 19th centuries were not focused on the North Sea, though the Napoleonic Wars saw some naval battles, the British Navy generally outclassed it's rivals and did not face a challenge to its dominance of the North Sea until World War I. During the First World War the North Sea became the main theatre of the war for surface action. The Second World War also saw action in the North Sea, including the German invasion of Norway, and large scale aerial warfare, though surface actions were very restricted.

After the war, the North Sea lost much of its military significance because it is bordered only by NATO member-states. However, its economic significant grew when in the 1960s states on the North Sea coasts began full-scale exploitation of its oil and gas resources. The North Sea continues to be an active trade route. The countries bordering the North Sea all claim the 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) of territorial waters within which they have exclusive fishing rights. Today, the North Sea is more important as a fishery and source of fossil fuel and renewable energy, since territorial expansion of the adjoining countries has ceased.

Naming

One of the earliest recorded names was Septentrionalis Oceanus, or "Northern Ocean" which was cited by Pliny.[2] However, the Celts who lived along its coast referred to it as the Morimaru, the "dead sea", which was also taken up by the Germanic peoples, giving Morimarusa.[3] This name may refer to the dead water patches resulting from a layer of fresh water sitting on top of a layer of salt water making it quite still.[4] Names referring to the same phenomenon lasted into the Middle Ages, e.g., Old High German mere giliberōt and Middle Dutch lebermer or libersee. Other common names in use for long periods were the Latin terms Mare Frisicum,[5] Oceanum- or Mare Germanicum[6] as well as their English equivalents, "Frisian Sea",[7] "German Ocean",[8] "German Sea"[9] and "Germanic Sea" (from the Latin Mare Germanicum).[10][11]

Early history

Prehistory

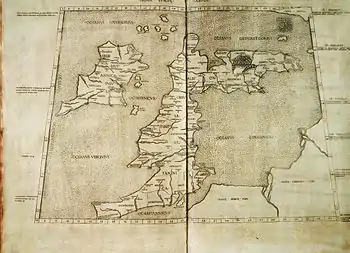

Archaeological findings indicate that the area that now comprises the North Sea may have been a large area of plains in prehistoric times, until around 8,000–6,000 BC.[12] The data suggests the area was inhabited before being flooded by rising water at the end of the last ice age.[12] In 2008, a finding of approximately 28 Stone Age handaxes in material from the bottom of the North Sea strengthened the evidence of human settlements in the area.[13]

Roman Empire

The first historically confirmed intensive use of the North Sea was by the Romans in 12 BC, when Nero Claudius Drusus built and launched a fleet of over a thousand ships into the North Sea conquering the indigenous tribes, including the Frisii and the Chauci. By 5 BC the Roman knowledge of the Sea was greatly expanded as far as the Elbe by a military expedition under Tiberius. Pliny the Elder describes Roman sailors going through Helgoland and as far as the northeast coast of Denmark.[14]

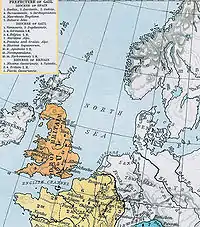

Julius Caesar's invasions of Britain in 55 BC and 54 BC were intended to punish those tribes who had supported the rebels in Gaul [15] and with the later conquest of Britain by Aulus Plautius in 43 AD, regular trade began between Rome and Britain via ports in Gaul. Using Roman naval support along the North Sea coast of Scotland, Gnaeus Julius Agricola continued the invasion and exploration northward into the Scottish Highlands. This traffic continued to some extent even after Emperor Honarius abandoned responsibility for defending Britain in 410 AD.

Migration period

In the power vacuum left by Rome, the Germanic Angles, Saxons, and Jutes began the next great migration across the North Sea. Having already been used as mercenaries in Britain by the Romans, many people from these tribes migrated across the North Sea during the Migration Period, Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain mixing with the native Celtic and Romano-British populations.[16]

Around the 7th century a wave of Frisian migrants moved to several islands in the North Sea, and a second wave moved to what is now Nordfriesland in northern Germany and South Jutland in southern Denmark in the 11th century.

Vikings

The attack on Lindisfarne in 793 is generally considered the beginning of the Viking Age.[17] For the next 250 years the Scandinavian raiders of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark dominated the North Sea, raiding monasteries, homes, and towns along the coast and along the rivers that ran inland. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle they began to settle in Britain in 851. They continued to settle in the British Isles and the continent until around 1050.

Alfred the Great, who is counted as the first English king, was the first to mount significant opposition to the Vikings. Eventually he relegated them to the Danelaw, carving out his own kingdom. Harthacanute of Denmark and England was the last Viking king to rule over a territory spanning the North Sea. After Harthacanute's death, the kingdom broke apart.[18]

With the rise of William the Conqueror the North Sea began to lose its significance as an invasion route. The new order oriented most of England and Scandinavia's trade south, toward the Mediterranean and the Orient. The Baltic Sea became increasingly important for northern Germany and Scandinavia as well as the powerful Hanseatic League began to rise.

Hanseatic League

Though the Hanseatic League was centered in the Baltic, it also had important Kontors on the North Sea, including Bergen, the Steelyard in London, and Bruges.[19]

The rise of Bruges as a center of trade and a corresponding revival of the North Sea economic importance began in 1134 when a storm tide created a deeper waterway to the city allowing the entry of large ships to port. A lively trade sprang up between Bruges and London, mostly in textiles. Bruges became the end point of the Hanseatic East-West trade line that began in Novgorod and was very important for maritime connections between France, Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands and the Hanseatic regions of Northern Europe. The Hanseatic league monopolised trade of the Northern Isles during this era.[20]

in 1441 the Hanseatic League was forced to recognize the equality of the Netherlands as Antwerp had risen as an economic power and tied itself to Denmark. After the so-called Count's Feud, a war of succession in Denmark, the Dutch were able to encroach upon the League's monopoly on Baltic trade and the reign of the Hanseatic League was at an end as the Netherlands became the center of the Northern European economy.

Renaissance

The Renaissance, a period of great cultural change and achievement in Europe that spanned the period from the end of the 14th century to about 1600, marking the transition between Medieval and Early Modern Europe. The majority of commerce took place via maritime shipping due to undeveloped roadways between the 16th and 18th centuries. The east coast of Great Britain operated several ports for intercontinental trade. The European coastal ports supplied domestic goods, dyes, linen, metal products, salt and wine. The Scandinavian and Baltic shoreline provided fish, grain, naval goods, and timber. The Mediterranean area traded dyes, premium cloths, fruits and spices.[20] The Burgundian Netherlands, French Netherlands, Spanish Netherlands and Austrian Netherlands and German lands were a central focus situated on the banks of the North Sea or the English Channel. Antwerp experienced three booms during its golden age, the first based on the pepper market, a second launched by American silver coming from Seville (ending with the bankruptcy of Spain in 1557), and a third boom, after the stabilising Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, in 1559, based on the textiles industry becoming the second largest European city north of the Alps by 1560.[20]

Early modern history

The Netherlands

In the 16th century, the Netherlands became the preeminent economic power in the world. For the Dutch merchant marine the North Sea served more as a starting point for their oceanic voyages. It had become the gateway and crucial outlet allowing Dutch merchants direct access to world markets.[21]

During the Eighty Years' War, the Dutch began a heavily invested worldwide trade – hunting whales around Svalbard, trading spices from India and Indonesia, founding colonies in Brazil, South Africa, North America (New Netherlands), and the Caribbean. The empire, which they accumulated through trade, led to the Dutch Golden Age in the 17th century. The Dutch fishing industry peaked in the early 17th century. The Herring Buss improved harvest of herring, and the Dutch also expanded to cod and whale fisheries.[20]

In 1651, England passed the Navigation Acts, which damaged Dutch trade interests. The disagreements concerning the Acts led to the First Anglo–Dutch War, which lasted from 1652–1654 and ended in the Treaty of Westminster (1654), whereby the Dutch were forced to recognize the acts.[20]

_-_De_verovering_van_het_Engelse_admiraalschip_de_'Royal_Prince'.jpg.webp)

In 1665 the English declared war on the Dutch once again, beginning the Second Anglo-Dutch War. With the support of the French, who, between the war, had marched into the Spanish Netherlands—present day Belgium, the Dutch gained the upper hand. In 1667, following Admiral de Ruyter's destruction of a large part of the British fleet on the Medway, the English and the Dutch signed the Treaty of Breda The peace dictated that the English would take over administration of Dutch possessions in North America (present day New York City) while the Dutch would get Suriname from the English and were able to amend the Navigation Acts.

1672 is known in the Netherlands as "Rampjaar," the year of disaster. England declared war on the Netherlands once again, beginning the Third Anglo-Dutch War, and were quickly followed by France, the Prince-Bishopric of Münster, and the Archbishopric of Cologne in an alliance against the Dutch. The three continental allies advanced on the Netherlands while the landing of English troops along the coast was only barely prevented.[22] By flooding parts of the country, which lie below sea level, William of Orange was able to hold off further advances and a Dutch victory in the Battle of Solebay enabled the Dutch to sue for peace. However, the ascension of the Dutch Prince William to the English throne, after overthrowing the Catholic Stuart dynasty, in the Glorious Revolution caused a dramatic shift in commercial, military, and political power from Amsterdam to London.[23] This shift combined with constant wars against a variety of foes and economic recession pushed the Netherlands out of the top tier of European powers by the end of the War of Spanish Succession.

England

England's climb to the pre-eminent sea power of the world began in 1588 as the attempted invasion of the Spanish Armada was defeated by the combination of outstanding naval tactics by the English under command of Sir Francis Drake and the breaking of the bad weather. The strengthened English Navy waged several wars with their neighbors across the North Sea and by the end of the 17th century had erased the Dutch's previously world-spanning empire.[24]

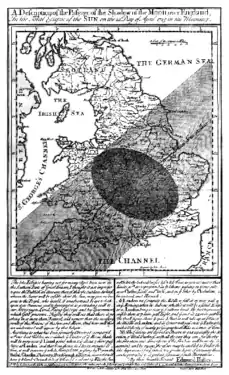

The building of the British Empire as a domain on which the sun never set was possible only because the British navy exercised unquestioned control over the seas around Europe, including the North Sea. In the late 18th century, Britain's naval supremacy faced a new challenge from Napoleonic France and her continental allies. In 1800, a union of lesser naval powers, called the League of Armed Neutrality, was formed to protect neutral trade during Britain's conflict with France. The British Navy defeated the combined forces of the League in the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801 in the Kattegat.[25] French plans for an invasion of Britain were focused on the English Channel, but a series of mishaps and a decisive British naval victory in the Battle of Trafalgar, off the coast of Spain, put them to rest. After Napoleon's fall, Britain was the preeminent power in Europe and the world. The Victorian Era was a long period of prosperity and growth for England, often referred to as the Pax Britannica or British Peace.[20]

Scotland

Scotland emerged as a prominent economic power during the Scottish Enlightenment of the 18th century.[26][27] This era established a great herring fishing industry resulting in Scotland becoming a European leader in that industry.[20]

19th century

During the First Schleswig War (1848–51), the Crimean War (1854–56) and the Second Schleswig War (1864), belligerents took steps to reduce or eliminate commerce in the North Sea by their enemies. In the first Schleswig War, Denmark was able to halt maritime commerce by Germany in the North Sea and in the second, imposed tolls on ships crossing through the Danish straits between the Baltic and North Seas. The Crimean War saw British and French expeditions sent into the Baltic to prevent Russian ships' egress into the North Sea though they saw little action.[28]

The Austro-Prussian War (1866) resulted in Prussia's gaining full control of the Kiel Canal, allowing their Baltic ports access to the North Sea.[29]

France declared war on Prussia 19 July 1870 which initiated the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). The French Navy was, at the time far larger and superior to the North German Federal Navy, the Navy of the North German Confederation. Though the French did take a number of merchant ships bound to and from North Germany, shortages of manpower and coal, as well as conflicting orders, made the attempted blockade of Prussian ports ineffective.[30] The French had planned a seaborne assault on the North Sea coast in order to relieve expected pressure on the front in Alsace and Lorraine. However, this coast, which was difficult to navigate to begin with, had been heavily fortified before the war.[31] The ironclads of this time consisted of broadside turret and the new casemate ironclads which protected the revolving turret.[32]

A convention passed in November 1887 came to the aid of fishermen of the North Sea. This law restricted liquor traffic from bum boats.[33] The island of Heligoland was ceded to Germany 1890 when the United Kingdom and Germany signed the Treaty of Heligoland.[34] The Cod War of 1893 erupted between Denmark and Britain over fishing territories. Denmark declared a fishing territory of 13 nautical miles (24 km) around their shores which included Iceland and the Faroe Islands. Britain did not acknowledge this claim.

20th century

The Dogger Bank Incident

Tensions in the North Sea were again heightened in 1904 by the Dogger Bank incident, in which Russian naval vessels mistook British fishing boats for Japanese ships and fired on them, and then upon each other. The incident, combined with Britain's alliance with Japan and the Russo-Japanese War led to an intense diplomatic crisis. The crisis was defused when Russia was defeated by the Japanese and agreed to pay compensation to the fishermen.[35]

The First World War

During the First World War, Great Britain's Grand Fleet based at Scapa Flow and Germany's Kaiserliche Marine faced each other across the North Sea.

Due to its numerical advantage in dreadnoughts, the Grand Fleet obtained Naval superiority and was able to establish a sea blockade of Germany's coast. The goal of the blockade was to deny Germany access to maritime trade including war materials and to guarantee the undisturbed ferrying of British troops. Because of the strong defensive fortress of Heligoland, the Germans controlled the German Bight, while the rest of the North Sea and the English Channel were controlled by the Royal Navy for the duration of the war.

6 August 1914 saw the start of the German U-boat Campaign – two days after the United Kingdom declared war on Germany over the German invasion of Belgium, ten German U-boats left their base in Heligoland to attack Royal Navy warships in the North Sea.

The first sea battle, the Battle of Heligoland Bight took place on 28 August 1914 and ended in a clear British victory. Because of British surface naval superiority, the Germans initiated submarine warfare. After several failures, the German submarine SM U-9 succeeded in sinking three British armored cruisers about 50 kilometres (27 nmi) north of Hoek van Holland, near the North Sea entrance to the English Channel. [36]

This ended British complacency about submarines.

In November 1914, the British declared the entire North Sea a war zone and from there on out it was mined. Ships that sailed the North Sea under the flags of neutral countries without giving the British prior warning could be the target of British attack.

In the Battle of Dogger Bank (1915), the Germans suffered another defeat on the 24 January 1915 and in the aftermath, all attempts to break the allied blockade failed. Due to these failures, on 4 February 1915, the Germans initiated unrestricted submarine warfare, in which, in addition to enemy ships, all neutral ships could be attacked.

On 31 May and 1 June 1916, the Battle of Jutland, if measured by the number of participating ships (238), the largest naval battle in world history took place. The German goal of significantly weakening the British Navy by sinking a large part of it and ending the blockade was not achieved. Although the Germans won a tactical victory, their main fleet narrowly escaped destruction and they once again laid their hopes on the unrestricted submarine warfare.[37]

As the war was ending and contrary to the wishes of the new German regime, a final attack on the British Navy on 28 October 1918 was ordered. However, the outbreak of the Wilhelmshaven mutiny in Kiel ended the naval war. The mutiny was also a crucial step in the initiation of the November Revolution.

The Second World War

The Second World War was, in terms of naval warfare, again mostly a submarine war on the German side. However, this time the main action was not in the North Sea but rather the Atlantic. Also different from the first war, the North Sea was no longer the exclusive territory of the Allies. Rather, it was, above all in the first years of the war, the stage for an intensive coastal war, featuring mainly small vessels like submarines, minesweepers, and Fast Attack Craft.[38] However, despite early successes, which brought about a supply crisis in Britain, the Germans did not succeed in breaking the British resistance. Like in the first war, the allies soon controlled the seas, especially due to air superiority and cut Germany off from supplies coming overseas.

On 14 October 1939, Korvettenkapitän Günther Prien of U-47 managed to sink the warship HMS Royal Oak in the Scapa Flow with 1400 men aboard.

On 9 April 1940 the Germans initiated Operation Weserübung in which almost the entire German fleet was focused north toward Scandinavia. The military objectives of the operation were soon achieved (occupation of Norwegian ports, securing of iron supply, and the prevention of a northern front) and Norway and Denmark.[39] Throughout the German occupation of Norway, the Shetland Bus operation ran secretly across the North Sea from Great Britain to Norway. Initially, Norwegian fishing boats were used. In the autumn of 1943 America supplied three 100-foot (30 m) submarine chasers named HNoMS Hessa, HNoMS Hitra and HNoMS Vigra. They were fast and efficient, carrying out 114 missions to Norway without loss.[40]

Because of the inferiority of the large battleships, especially after early losses (1939 German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee, 1940 German cruiser Blücher, and 1941 German battleship Bismarck), the German Kriegsmarine resorted more and more to small units with the remaining large ships almost dormant in the Norwegian fjords.

In the last years of the war and the first years thereafter under allied control, an abundance of weapons were dumped into the sea. While chemical weapons were mostly dumped in the Skagerrak and the Baltic, conventional weapons (grenades, mines, bazookas, and cartridges) were sunk in the German Bight. The estimates vary widely but it seems to be clear that more than a hundred thousand tons of munitions were sunk.

The Maunsell Sea Forts were small fortified towers built in the Thames and Mersey estuaries during the Second World War to help defend the United Kingdom. One of which on HM Fort Roughs is now occupied by the controversial Principality of Sealand.[41]

After the war

Post Second World War period, the North Sea, bounded entirely by NATO allies became completely peaceful whilst significant Cold War confrontation began in the Baltic. Its economic importance grew in the 1960s as surrounding countries began to exploit oil and gas resources. The largest environmental catastrophe in the North Sea was the destruction of the offshore oil platform Piper Alpha in 1988 in which 167 people lost their lives.

Political status

Although de facto control of the North Sea played a decisive role in the political power relationships in north-west Europe since the time of the Vikings, and became a question of world politics after the First Anglo-Dutch War, until after the Second World War the bordering countries officially claimed no more than narrow coastal waters. In the last few decades things have changed.

The countries bordering the North Sea all claim the twelve nautical miles (22 km) of territorial waters within which they have, for example, exclusive fishing rights. Iceland, however, as a result of the Cod Wars has exclusive fishing rights for 200 miles (320 km) from its coast, into parts of the North Sea. The Common Fisheries Policy of the EU exists to coordinate fishing rights and assist with disputes between EU states and the EU border state of Norway.

After the discovery of mineral resources in the North Sea, Norway claimed its rights under the Continental Shelf Convention and the other countries on the sea followed suit. These rights are largely divided along the median line, defined as the line "every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured."[42] Only for the border between Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark was the ocean floor otherwise divided after protracted negotiations and a judgment of the International Court of Justice[43] according to which Germany, by reason of its geographic position, received a smaller section of the ocean floor in relation to its coastline, than the other disputants.

In relation to environmental protection and marine pollution the MARPOL 73/78 Accords created 25- and 50-mile (40 and 80 km) zones of protection. Furthermore, the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic concerns itself directly with the question of the preservation of the ocean in the region. Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands have a trilateral agreement for the protection of the Wadden Sea, or mudflats, which run along the coasts of the three countries on the southern edge of the North Sea.

The European Maritime Safety Agency has monitored and coordinated all sea traffic through the sea since its inception in 2003. While the Agency is part of the EU, non-member states Norway and Iceland have seats in the agency as they are directly affected.

See also

- Battle of the Atlantic

- Battle of Dogger Bank (1781)

- Battle of Camperdown – French revolutionary wars

- Battle of Coronel – World War I battle

- Battle of Goodwin Sands -First battle of First Anglo-Dutch War

- Battle of Marston Moor

- Battle of the Somme – World War I battle

- Battle of Schooneveld – Franco-Dutch War of 1672–1678

- Campaigns of World War II – Battle of the Atlantic

- de Havilland Mosquito – World War II transport aircraft

- Frisians – Mare Frisia first North Sea naming.

- History of Germany – World War I blockade

- History of the Netherlands – Roman era and Frisian realm Greater Frisia or Frisia Magna

- History of Scotland – Exodus of Norwegians in WWI

- History of Sweden (1772–1809) – 1794 Scandinavian wars

- History of whaling

- Invasion of Poland (1939) – Polish Navy joined with the British Royal Navy.

- Lotharingia – Medieval short-lived kingdom in western Europe

- Maritime history

- Namsos Campaign – World War II

- Nine Years' War – (1688–97) Dutch convoy struck in the North Sea

- Operation Sea Lion – cancelled World War II operation

- Ragnar Lodbrok – Norse legendary hero from the Viking Age

- Zeppelin – Zeppelin crash and addeWorld War I reconnaissance

References

- Dollinger 1999: 62

- Roller, Duane W. (2006). "Roman Exploration". Through the Pillars of Herakles: Greco-Roman Exploration of the Atlantic. Taylor and Francis. p. 119. ISBN 0-415-37287-9.

Footnote 28. Strabo 7.1.3. The name North Sea - more properly "Northern Ocean." Septentrionalis Oceanus - probably came into use at this time; the earliest extant citation is Pliny, Natural History 2.167, 4.109.

- Akin to Welsh môr "sea" and marw "dead"; the -sa suffix is a Proto-Germanic form akin to English sea.

- Oskar Bandle, Kurt Braunmuller, Lennart Elmevik, and Gun Widmark, The Nordic Languages: An International Handbook of the History of the Northern Germanic Languages (Leiden, Netherlands: Walter de Gruyter, 2002), 596.

- Thernstrom, Stephan; Ann Orlov; Oscar Handlin (1980). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-37512-2.

- Sherman, William Howard (1997). "Writings". John Dee: The Politics of Reading and Writing in the English Renaissance. Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. 197. ISBN 1-55849-070-1.

- Looijenga, Tineke (2003). "Chapter 2 History of Runic Research". Texts & Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions. BRILL. p. 70. ISBN 90-04-12396-2.

- "Prof. Hennessy on the Distribution of Heat. (Table continued)". Philosophical Magazine (Digitised 19 April 2007 by Googlebooks online). 4. 16. University of California: Taylor & Francis. 1858. p. 256. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- "Eur". Encyclopædia Britannica; Or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature: Or, A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, Enlarged and Improved (Digitised 26 January 2007 by Google Books online). 8. Original from the University of Michigan: Archibald Constable and Company. 1823. p. 351.

- Malte-Brun, Conrad (1828). "Physical Geography". Universal Geography: Or a Description of All Parts of the World, on a New Plan, According to the Great Natural Divisions of the Globe; Accompanied with Analytical, Synoptical, and Elementary Tables (Digitized April 16, 2007). 6. Wells and Lilly. p. 5.

- Professor Shin Kim of Kyunghee University. "On the History of Naming the North Sea Medieval usages". With the 21st century just ahead, the world closed the age of discord and antagonism and is opening. East Sea Forum article 3. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2008-11-23.Other names were Amalchium Mare, Britannie ef Frisie mare, Fresonicus Oceanus, Magnum Mare, Occidentale Mare, Occidentalis Oceanus. In all adjacent territories, the local name for the North Sea refers to the northern quarter of the compass, even though the sea is actually south of those areas. Danish and German however use or have used a translation of 'West Sea' as well.

- "BBC NEWS | UK | Education | Lost world warning from North Sea". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- Handwerk, Brian (2008-03-17). "Stone Age Hand Axes Found at Bottom of North Sea". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- By Redbad. "HISTORY OF THE FRISIAN FOLK Permission granted for publication on Boudicca's Bard – Part One – (1750 B.C. – 785 A.D.) Origins of the Frisians (1750 B.C. – 700 B.C.)". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- "The Roman Conquest of Britain". Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- "Germany The migration period". Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 2007-07-24. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Graham-Campbell, James; David M. Wilson (2001). "Salt-water bandits". The Viking World (Digitized by Internet Archive online) (3 ed.). London: Frances Lincoln Ltd. pp. 10 and 22. ISBN 0-7112-1800-5. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

Lindisfarne, or Holy Island, is a small tidal island off the coast of Northumbria where a monastery had been established in 634. Its shelving beaches provided a perfect landing for the shallow-draft ships of the Viking raiders who fell upon its unsuspecting and unprotected monks in the summer of 793. This bloody assault on a "place more venerable than all in Britain" was one of the first positively recorded Viking raids on the West. Page 21. Viking longships, with their shallow drafts and good manoeuvrability under both sail and oar, allowed their crews to strike deep inland up Europe's major rivers. Page 22. The world of the Vikings consisted of a loose grouping of the Scandinavian homelands and new overseas colonies, linked by sea routes that reached across the Baltic and the North Sea, spanning even the Atlantic. Page 10.

- "British Kings and Queens – Historical Timeline". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- David K. Schreur. "The Hanseatic League". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Smith, H.D. (April 1992). "The British Isles and the Age of Exploration – A Maritime Perspective". GeoJournal. 26 (4): 483–487. doi:10.1007/BF02665747.

- Donald J. Harreld, Brigham Young University. "EH.Net Encyclopedia: Dutch Economy in the "Golden Age" (16th–17th Centuries)". Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- David Ormrod, University of Kent. "The North Sea as a core region in the early modern world: the shift from Amsterdam to London" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- "Short History of the Anglo Dutch Wars". The Contemplator. Retrieved 2008-11-02. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - britishbattles.com (2007). "The Spanish Armada : Sir Francis Drake". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Claus Christiansen (1997). "War with England 1801–1804". Danish Military History. Archived from the original on 2008-09-26. Retrieved 2008-11-02. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Broadie, Alexander (2003). The Cambridge Companion to the Scottish Enlightenment (digitised by Google books online). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00323-7. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- Muller, Jerry Z. (1995). Adam Smith in His Time and Ours: Designing the Decent Society (digitised by Google books online). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00161-8. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- Sweetman, John (2001). The Crimean War. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-186-2.

- Wawro, Geoffrey. The Austro-Prussian War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62951-5.

- Rüstow, Wilhelm; John Layland Needham (1872). The War for the Rhine Frontier, 1870: Its Political and Military History. Blackwood. pp. 229–235.

- Wawro, Geoffrey (2003). The Franco-Prussian War: The German Conquest of France 1870–1871. Cambridge University Press. pp. 190–192.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1958). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914 – Chapter The Ironclad Revolution. Routledge online. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-415-21477-3.

- Butler, Geoffrey G.; Simon, Maccoby (2003). The Development of International Law. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-58477-215-6.

- Fat, Chow Ka. "A Chronology of World Political History (1851 – 1900 C.E.)". Archived from the original on 2009-10-27. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- "Dogger Bank: Voyage of the Damned". Hull Webs: History of Hull. 2004. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- worldwar1.co.uk (1998–2006). "Background to the Battle of Heligoland Bight". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- worldwar1.co.uk (1998–2006). "Battle of Jutland". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Campaigns of World War 2, Naval History Homepage. "Atlantic, WW2, U-boats, convoys, OA, OB, SL, HX, HG, Halifax, RCN ..." Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- LemaireSoft (November 18, 2005). "LemaireSoft's Naval Encyclopedia of World War 2: Hipper". Archived from the original on May 18, 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- "Shetland Bus: The Operation". Shetland Heritage. Archived from the original on 2008-09-17. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- Hodgkinson, Thomas (17 May 2013). "Notes from a big small island: Is Sealand an independent micronation or an illegal fortress?". The Independent. London. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- The Multilaterals Project, The Fletcher School, Tufts University (29 April 1958). "Convention on the Continental Shelf, Geneva". Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-24.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- International Court of Justice (20 February 1969). "North Sea Continental Shelf Cases". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Dollinger, Philippe (1999). The German Hansa. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-19072-X.