Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis; Chinese: 中華白海豚; pinyin: Zhōnghuá bái hǎitún)[2] is a species of humpback dolphin inhabiting coastal waters of the eastern Indian and western Pacific Oceans.[3] This species is often referred to as the Chinese white dolphin in China (including Macao), Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore as a common name. Some biologists regard the Indo-Pacific dolphin as a subspecies of the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (S. plumbea) which ranges from East Africa to India. However, DNA testing studies have shown that the two are distinct species.[1] Additionally, a new species (the Australian humpback dolphin (S. sahulensis)) has just recently been split off from S. chinensis and recognized as a distinct species. Nevertheless, there are still several unresolved issues in differentiation of the Indian Ocean-type and Indo-Pacific-type humpback dolphins.

| Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

| At the theme aquarium in Pattaya, Thailand. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Sousa |

| Species: | S. chinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Sousa chinensis (Osbeck, 1765) | |

| |

| Combined ranges of Sousa chinensis and Sousa sahulensis | |

Description

_by_Zureks.jpg.webp)

An adult Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin is grey, white or pink and may appear as an albino dolphin to some. Uniquely, the population along the Chinese coast has pink skin,[4] and the pink colour originates not from a pigment, but from blood vessels which were overdeveloped for thermoregulation. The body length is 2 to 3.5 m (6 ft 7 in to 11 ft 6 in) for adults 1 m (3 ft 3 in) for infants. An adult weighs 150 to 230 kg (330 to 510 lb). Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins live up to 40 years, as determined by the analysis of their teeth.

At birth, the dolphins are black. They change to grey, then pinkish with spots when young. Adults are grey, white or pink.

Behaviour

Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins come to the water surface to breathe for 20 to 30 seconds before diving deep again, for two to eight minutes. Dolphin calves, with smaller lung capacities, surface twice as often as adults, staying underwater for one to three minutes. Adult dolphins rarely stay under water for more than four minutes. They sometimes leap completely out of the water. They may also rise up vertically from the water, exposing the dorsal half of their bodies. A pair of protruding eyes allows them to see clearly in both air and water.

Reproductive cycle

Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins are sociable creatures and live in groups of three to four. Female dolphins become mature at 10 years old, while the males become mature at 13 years old. They usually mate from the end of summer to autumn. Infant dolphins are usually born 11 months after the mating. Mature females can give birth every three years, and parental care lasts until their offspring can find food themselves.

Humans and the environment

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin is threatened by both habitat loss and pollution. Conservationists warn that Hong Kong may lose its rare Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins, also known as pink dolphins for their unique colour, unless China takes urgent action against pollution and other threats. Their numbers in Hong Kong waters have fallen from an estimated 158 in 2003 to just 78 in 2011, with a further decline expected by the Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society. A tour guide from Hong Kong Dolphinwatch spotted a group of pink dolphins helping a mother support the body of her dead calf above the water in an attempt to revive it. The scene, captured on video and widely shared on Facebook, has raised fresh concerns about the dwindling population in a city where dolphin watching is a tourist attraction. "We’re 99 percent certain the calf died from toxins in the mother’s milk, accumulated from polluted seawater," said Hong Kong Dolphinwatch spokeswoman Janet Walker, who added it was the third such incident reported in April alone. Fewer than 2,500 of the mammals survive in the Pearl River Delta, the body of water between Macau and Hong Kong, with the majority found in Chinese waters and the rest in Hong Kong.[5]

The impact of plastic pollution

The subject of plastic pollution is a global phenomenon that has no end in sight. Plastic pollution is widespread across all entangling oceans due to their buoyant and durable properties that allow for sorption of toxicants to plastic while traveling through the environment.[6][7] This lead researchers to the conclusion that synthetic polymers are hazardous to marine life and should be declared as a hazardous waste type. There are many transit paths that allow for plastics and pollutions to enter oceans. Freshwater waste can enter oceans by rivers; delta or estuary (where rivers meet the ocean). Human populations discarding their waste directly into marine waters. Through photo-degradation and other forms of weathering processes that aid in plastics fragmentation and dispersal. Mass quantities of fragmented plastics - along with pollution are aggregated in subtropical gyres; ocean gyres.[7] Plastic accumulation is not limited to ocean gyres; closed bays, gulfs and seas surrounded by densely populated coastlines and watersheds are all susceptible.[8]

"The Pearl River Delta is an estuary within the proximity of one of the many ocean gyres that the Humpback dolphin inhabits. A tour guide from Hong Kong Dolphinwatch spotted a group of pink dolphins helping a mother support the body of her dead calf above the water in an attempt to revive it. The scene, captured on video and widely shared on Facebook, has raised fresh concerns about the dwindling population in a city where dolphin watching is a tourist attraction. "We’re 99 percent certain the calf died from toxins in the mother’s milk, accumulated from polluted seawater," said Hong Kong Dolphinwatch spokeswoman Janet Walker, who added it was the third such incident reported in April alone. Fewer than 2,500 of the mammals survive in the Pearl River Delta, the body of water between Macau and Hong Kong, with the majority found in Chinese waters and the rest in Hong Kong."[5] (Refer to: Humans and the environment subsection above)

- Microplastics: Very small pieces of plastic that pollute the environment (typically < 5 mm)

- Mesoplastics: Plastic particles found especially in the marine environment (typically about 5 mm)

- Macroplastics: Relatively large particles of plastic found especially in the marine environment (> 5 mm).

Plastic pollution can severely affect all forms of marine life; Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins are specifically affected in an array of means.

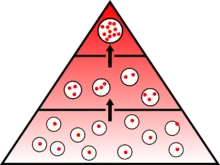

Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) are chronically exposed to organic pollutants since they inhabit shallow coastal waters that are often impacted by anthropogenic activities. Anthropogenic pollutants pose a risk to marine mammals that reside in coastal waters. Discharge of organic pollutants into marine environments has been shown to decrease water quality resulting in loss of habitats and a significant reduction in the species richness (Johnston and Roberts, 2009).[9] The loss of key pods have caused specie fragmentation, also due to habitat loss, which inclines specie isolation; decrease connectivity resulting in population decline. This loss in population is what lead this species to be labeled as near threatened on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The consumption of plastics have adverse effects in marine mammals such as disease susceptibility, reproductive and developmental toxicity.[9] Constant absorption of organic pollutants like plastic can be transferred into the dolphin's tissues and organs through an ingestion pathway that is impacting megafauna, lower trophic levels and predators (not limited to Indo-Pacific)[10] Organ toxicity can lead to organ failure, loss of offsprings and milk toxicity. If the dolphin is not consuming plastic directly then it can have plastic pollutants ingested though biomagnification and bioaccumulation. Bioaccumulation is defined as the uptake of chemicals from the environment through dietary intake, dermal absorption or respiratory transport in air or water. This is a huge factor is plastic toxicity consumption in this species due to them having long lifespans which makes them susceptible to chronic exposure. Also, they contain a large quantity of blubber, lipids, which can result in an excess of toxicity storage in their tissues.

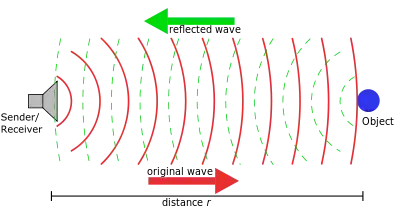

Echolocation is a main sense that all dolphins use to navigate and pinpoint prey and predators. Dolphins and whales use echolocation by bouncing high-pitched clicking sounds off underwater objects, similar to shouting and listening for echoes. The sounds are made by squeezing air through nasal passages near the blowhole. These sound-waves then pass into the forehead, where a big blob of fat called the melon focuses them into a beam.[11] This process can be interrupted by large composites of waste that can range from oil, plastics and noise.[12] The large blockage can refract sound-waves that give the dolphin a false inclination that there is possible prey, kin or a predator in the area. This can become confusing and frustrating which can lead to extreme stress and potential health issues. Despite echolocation being mostly affected by noise pollution it can altered by pollutants in marine water.

Noise pollution can also be caused by large clusters of plastic debris; ocean gyre. The constant movement of ocean currents will cause the plastic debris, along with general-waste to clash together which entails a production of sound. Sound waves from the debris will travel through marine waters which can become an excess of sound waves traveling can render their use of echolocation. This can inherently leave this species blind since this is their primary sense.

Distributions and dolphin watching

In Hong Kong, boat trips to visit the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins have been running since the 1990s.[13] The dolphins mainly live in the waters of Lantau North, Southeast Lantau, the Soko Islands and Peng Chau. A code of conduct regulates dolphin-watching activity in Hong Kong waters.[14]

There have been some reports of dolphin watching practices that have further endangered the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins, such as in Sanniang Bay dolphin sanctuary in Qinzhou[15][16] and off Xiamen.[17] However, these generally are small, locally organised one-off tours or private pleasure boats that do not adhere to the Hong Kong Agricultural and Fisheries Department's voluntary code of conduct.

Nánpēng Islands Marine Sanctuary in Nan'ao County is also home to local pods.[18] The population in Leizhou Bay, Leizhou Peninsula, comprising nearly 1,000 animals and the second largest population in the nation, may also be targeted for future tourism.[19] Hepu National Sanctuary of Dugongs, and waters around Sanya Bay and other coasts adjacent on Hainan Island are home to some dolphins.[20] As the environment and local ecosystems recovery, dolphins' presences in nearby waters have been increasing such as vicinity to the nature sanctuary of Weizhou and Xieyang Islands.[21][22] Gulf of Tonkin waters in Vietnam may have unstudied populations that may appear elsewhere such as along Xuân Thủy National Park and Hòn Dáu Island in Hải Phòng.[23]

Cantonese slang

The Cantonese language has a slang expression wu gei bak gei (often written as 烏忌白忌, "black taboo white taboo") which means someone or something is a bad omen or a nuisance. The phrase originates from the Cantonese fisher people, because they claim the dolphins eat the fish in their nets. However, in formal Chinese, it should be written as 烏鱀白鱀, with the gei originally in olden Chinese, meaning dolphins. The wu refers to the finless porpoises, which are black, and the bak, white, referring to Chinese river dolphins. These two species often interrupt and ruin the fishermen's catch. As years passed, because "dolphin" sounds the same as "bad luck", the meaning of the phrase changed. However, in Cantonese, wu refers to the calves of Chinese white dolphin and bak refers to the adults. Nowadays, dolphins are not called gei anymore, but 海豚 (hai tun), literally meaning "sea pig", with none of the negative connotations for pig found in English.

Eastern Taiwan Strait (ETS) population

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins were first discovered along the west coast of Taiwan in 2002. Based on a survey done in 2002 and 2003, they are often found in waters <5m deep, and no evidence shows that they appear in water deeper than 15m.[24] A study in 2008 found that the population of humpback dolphins, which occupies a linear range of about 500 km^2 along the central west coast of Taiwan, is genetically distinct from all populations living in other areas.[25] And this population is called Eastern Taiwan Strait (ETS) population.

Taiwan is a densely populated island and highly developed area, which has many industrial development projects, especially along the west coast, where the ETS populations of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins live. Based on data collected between 2002 and 2005, the ETS population of humpback dolphins was less than 100 individuals.[24] Unfortunately, the newest data released in 2012 shows that only 62 individuals are left. It means during those 7 years, population of humpback dolphins is being destroyed constantly and severely. A preliminary examination revealed that the ETS humpback dolphin population meets the IUCN Red List criteria for "Critically endangered".[26] Without further protection and regulation, this population will go extinct quickly.

There are several facts that result in the decreasing number of ETS population of humpback dolphins. First, large-scale modification of the shoreline by industrial development including hydraulic filling for creating industrial or science parks, seawall construction and sand mining cause habitat fragmentation and diminish dolphin's habitats. In addition, exploitation of shoreline also contributes to toxic contamination flows into dolphin's habitats. The chemical pollution from industrial or agricultural and municipal discharge results in impaired health of dolphins, for instance, reproductive disorders, and compromised immune system.[27]

Second, fishing activities along the west coast of Taiwan are thriving, and cause many impacts on dolphins. Widespread and intensive use of gillnets and vessel strikes are potential threats for dolphins. Over exploitation of fish by fisheries' is another threat for the dolphin population. It has led to disturbance of marine food web or trophic level and reduces marine biodiversity. Therefore, dolphins have not enough prey to live on.

Still another problem is reduced amount of freshwater flows into estuaries from rivers. Since ETS population of humpback dolphins is closely associated with estuaries habitat, the elimination of freshwater discharge from rivers significantly decreases the amount of suitable habitats for dolphins.[24]

Hydroacoustic disturbance is another critical issue for dolphins. Sources of noise can come from dredging, pile driving, increased vessel traffic, seawall construction, and soil improvement. For all cetaceans, sound is vital for providing information about their environment, communicating with other individuals, and foraging; also, they are very vulnerable and sensitive to the effects of noise. Elevated anthropogenic sound level causes many dysfunctions of their behaviors, and even leads to death.[24]

In addition to threats from anthropogenic activities, dolphins are potentially at the risk due to the small population size, which may result in inbreeding and decreased genetic and demographic variability. Finally, climate change causes more typhoons to hit the west coast of Taiwan and cause great disturbance to dolphins' habitats.

Conservation

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin is listed on Appendix II[28] of the convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix II[28] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements. In the interim of 2003–2013, the number of these dolphins in the bay around Hong Kong has dwindled from a population of 159 to just 61 individuals, a population decline of 60% in the last decade. The population continues to be further threatened by pollution, vessel collision, overfishing, and underwater noise pollution.[29]

In addition to their natural susceptibility to anthropogenic disturbances, the Chinese white dolphin's late sexual maturity, reduced fecundity, reduced calf survival, and long calving intervals heavily curtails their ability to naturally cope with elevated rates of mortality.[30]

In recent years, Taiwan launched the largest Indo-Pacific Humpbacked Dolphin sanctuary on the Taiwanese coast, stretching from Miaoli County to Chiayi County.[31] The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin is also covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MoU).

Timeline of main events

- 1637: The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin was first documented in English by the adventurer Peter Mundy in Hong Kong near the Pearl River. The species are attracted to the Pearl River Estuary because of its brackish waters.

- 1765: Pehr Osbeck gives the first scientific description of the species.[32]

- Late 1980s: Environmentalists started to pay attention to the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin population.

- Early 1990: The Hong Kong public started to become aware of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin. This was due to the side effects of the construction of the Chek Lap Kok Airport. It was one of the world's largest single reclamation projects: the reclamation of nine square kilometers of the seabed near Northern Lantau, which was one of the major habitats of the dolphins.

- Early 1993: Re-evaluation of the environmental effects of the construction of Chek Lap Kok Airport. This alerted eco-activists such as those from the World Wide Fund for Nature in Hong Kong, in turn bringing media attention on the matter. Soon enough, the Hong Kong Government began getting involved by funding projects to research on the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins

- Late 1993: The Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department was founded.

- 1996: Dr. Thomas Jefferson began to conduct research on the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in hope of discovering more about them.

- 1997: The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin became the official mascot of the 1997 sovereignty changing ceremonies in Hong Kong.

- 1998: The research results of Dr. Thomas Jefferson was published in "Wildlife Monographs".

- 1998: The Hong Kong Dolphinwatch was organized and began to run dolphin watching tours for the general public to raise the public's awareness of the species.

- 2000: The Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department started to conduct long-term observation of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in Hong Kong.

- 2000: The population of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins has reached around 80–140 dolphins in the Pearl River waters.

- 2014: Dr. Thomas Jefferson and Dr. Howard C. Rosenbaum revised the taxonomy of the humpback dolphins (Sousa spp.). They describe a new species, the Australian humpback dolphin and define the accepted common name for this species, the Indo-Pacific Humpback dolphin.[33]

See also

References

- Jefferson, T.A.; Smith, B.D.; Braulik, G.T.; Perrin, W. (2017). "Sousa chinensis (errata version published in 2018)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T82031425A123794774. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T82031425A50372332.en.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link){{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help)

- Mead, J.G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Sousa chinensis". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 732. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Jefferson, Thomas A.; Smith, Brian D. (2016), "Re-assessment of the Conservation Status of the Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin (Sousa chinensis) Using the IUCN Red List Criteria", Advances in Marine Biology, Elsevier, 73: 1–26, doi:10.1016/bs.amb.2015.04.002, ISBN 978-0-12-803602-0, PMID 26790886

- WWF Hong Kong. Wwf.org.hk. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- Conservationists warn: Hong Kong risks losing rare ‘pink dolphins’. articlechase.com

- Teuten, Emma L.; Rowland, Steven J.; Galloway, Tamara S.; Thompson, Richard C. (1 November 2007). "Potential for Plastics to Transport Hydrophobic Contaminants". Environmental Science & Technology. 41 (22): 7759–7764. Bibcode:2007EnST...41.7759T. doi:10.1021/es071737s. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 18075085.

- Eriksen, Marcus; Lebreton, Laurent C. M.; Carson, Henry S.; Thiel, Martin; Moore, Charles J.; Borerro, Jose C.; Galgani, Francois; Ryan, Peter G.; Reisser, Julia (10 December 2014). "Plastic Pollution in the World's Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e111913. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1913E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111913. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4262196. PMID 25494041.

- Reisser, Julia; Shaw, Jeremy; Wilcox, Chris; Hardesty, Britta Denise; Proietti, Maira; Thums, Michele; Pattiaratchi, Charitha (2013). "Marine plastic pollution in waters around Australia: characteristics, concentrations, and pathways". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e80466. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880466R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080466. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3842337. PMID 24312224.

- Sanganyado, Edmond; Rajput, Imran Rashid; Liu, Wenhua (2018). "Bioaccumulation of organic pollutants in Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin: A review on current knowledge and future prospects". Environmental Pollution. 237: 111–125. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.055. PMID 29477865.

- Teuten, Emma L.; Saquing, Jovita M.; Knappe, Detlef R. U.; Barlaz, Morton A.; Jonsson, Susanne; Björn, Annika; Rowland, Steven J.; Thompson, Richard C.; Galloway, Tamara S.; Yamashita, Rei; Ochi, Daisuke (27 July 2009). "Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 364 (1526): 2027–2045. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0284. ISSN 1471-2970. PMC 2873017. PMID 19528054.

- "What is echolocation and which animals use it?". Discover Wildlife. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Nabi, G.; McLaughlin, R. W.; Hao, Y.; Wang, K.; Zeng, X.; Khan, S.; Wang, D. (2018). "Access to University Library Resources | The University of New Mexico". Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 25 (20): 19338–19345. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-2208-7. PMID 29804251. S2CID 44108995.

- "Hong Kong DolphinWatch Ltd".

- Code of Conduct for Dolphin Watching Activities, Hong Kong Agricultural and Fisheries Department. (PDF). Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- Plight of dolphins major issue amid city expansion. China Daily. (3 September 2010). Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- Show China. En.showchina.org. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- 厦门海之风游艇带您来五缘湾看海豚_厦门海之风游艇有限公微信文章_微儿网. V2gg.com. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- 2016. 汕头南澎青罗湾保护区:"美人鱼"和精灵们的海域 Archived 22 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "近千头中华白海豚栖息广东湛江雷州湾". Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- 2016. 海南海洋生态保护良好,成为大型珍稀海洋动物的"乐园" Archived 5 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 March 2017

- 2014. 涠洲岛景区现海豚殒命:消息不实 Archived 7 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. 中国涠洲岛网. Retrieved 7 March 2017

- 涠洲岛旅游区管委会. 涠洲岛管委会. 2017. 加强海域环境保护,期待海豚"安居"涠洲. Retrieved 7 March 2017

- Công An Nhân Dân. 2006. Hải Phòng: Cá heo trắng xuất hiện cả đàn. Retrieved 7 March 2017

- Wang, John Y. et al. (eds.) (2007) CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN FOR THE EASTERN TAIWAN STRAIT POPULATION OF INDO-PACIFIC HUMPBACK DOLPHINS. National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium

- Population differences in the pigmentation of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins, Sousa chinensis, in Chinese waters : mammalia. Degruyter.com (17 October 2008). Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- Sheehy, D.J. (2009) Potential Impacts to Sousa chinensis from a. Proposed Land Reclamation along the West Coast of Taiwan. aquabio.com

- Wang, John Y. et al. (eds.) (2004) RESEARCH ACTION PLAN FOR THE HUMPBACK DOLPHINS OF WESTERN TAIWAN. The National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium

- "Appendix II Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009.

- Hong Kong's Striking Dolphins Dwindle to Just Dozens | ABC News Blogs – Yahoo. Gma.yahoo.com (21 June 2013). Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- Jefferson, Thomas A.; Hung, Samuel K. (2004). "A Review of the Status of the Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin (Sousa chinensis) in Chinese Waters". Aquatic Mammals. 30 (1): 149–158. doi:10.1578/am.30.1.2004.149.

- Perrin F.W., Koch C.C., 2007. Wursig B., Thewissen G.M.J, Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. pp609. Academic Press. Retrieved 13-05-2014

- Carwardine, Mark (2002) Sharks and Whales. DK ADULT. ISBN 0789489902. p. 362.

- Jefferson, Thomas A.; Rosenbaum, Howard C. (2014). "Taxonomic revision of the humpback dolphins (Sousa spp.), and description of a new species from Australia". Marine Mammal Science. 30 (4): 1494–1541. doi:10.1111/mms.12152.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Sousa chinensis chinensis. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sousa chinensis. |

- The Agriculture, Fishies and Conservation Department

- Hong Kong Dolphinwatch

- Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society

- Convention on Migratory Species page on the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin

- Official webpage of the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region