South Asian river dolphin

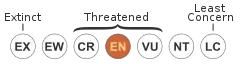

The South Asian river dolphin (Platanista gangetica) is an endangered freshwater or river dolphin found in the region of the Indian subcontinent, which is split into two subspecies, the Ganges river dolphin (P. g. gangetica, ~3,500 individuals) and the Indus river dolphin (P. g. minor, ~1,500 individuals). The Ganges river dolphin is primarily found in the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers and their tributaries in India, Bangladesh, and Nepal, while the Indus river dolphin is now found only in the main channel of the Indus River in Pakistan and active channels connected to it between the Jinnah and Kotri barrages, and in the River Beas (a tributary of the Indus) in Punjab in India.[3]

| South Asian river dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ganges river dolphin leaping out of the water | |

| |

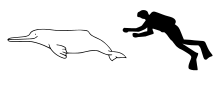

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Platanistidae |

| Genus: | Platanista Wagler, 1830 |

| Species: | P. gangetica |

| Binomial name | |

| Platanista gangetica (Lebeck, 1801); (Roxburgh, 1801) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Platanista gangetica gangetica | |

| |

| Ranges of the Ganges river dolphin and of the Indus river dolphin | |

From the 1970s until 1998, they were regarded as separate species; however, in 1998, their classification was changed from two separate species to subspecies of a single species (see taxonomy below). The Ganges river dolphin has been recognized by the government of India as its National Aquatic Animal[4] and is the official animal of the Indian city of Guwahati.[5] The Indus river dolphin has been named as the National Mammal of Pakistan.[6]

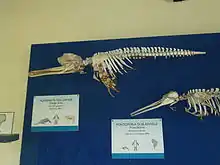

Taxonomy and evolution

The species was described independently by two authors, Lebeck and Roxburgh, both in 1801, and to whom the original description should be ascribed is unclear.[7] Until the 1970s, the South Asian river dolphin was regarded as a single species. The two subspecies are geographically separate and have not interbred for many hundreds if not thousands of years. Based on differences in skull structure, vertebrae, and lipid composition scientists declared the two populations as separate species in the early 1970s.[8] In 1998, the results of these studies were questioned and the classification reverted to the pre-1970 consensus of a single species containing two subspecies until the taxonomy could be resolved using modern techniques such as molecular sequencing. The latest analyses of mitochondrial DNA of the two populations did not display the variances needed to support their classification as separate species.[9] Thus, at present, a single species with two subspecies is recognized in the genus Platanista, P. g. gangetica (Ganges river dolphin) and P. g. minor (Indus river dolphin).[10]

- Synonyms

- blind river dolphin, side-swimming dolphin

- Ganges subspecies: Gangetic dolphin, Ganges susu,[11] shushuk

- Indus subspecies: bhulan, Indus dolphin, Indus blind dolphin

An assessment of divergence rates in mitochondrial DNA of the two subspecies indicates that they diverged from a common ancestor around 550,000 years ago. This ancestor is thought to have been a marine Platanistid inhabiting the epi-continental seas in South Asia during the sea level rises in the middle Miocene.[12] The earliest fossil identified as belonging to the species is only 12,000 years old.[1]

Description

The South Asian river dolphin has the long, pointed nose characteristic of all river dolphins. Their teeth are visible in both the upper and lower jaws even when the mouth is closed. The teeth of young animals are almost an inch long, thin and curved; however, as animals age, the teeth undergo considerable changes and in mature adults become square, bony, flat disks. The snout thickens towards its end. Navigation and hunting are carried out using echolocation.[13] They are unique among cetaceans in that they swim on their sides.[14] The body is a brownish color and stocky at the middle. The species has only a small, triangular lump in the place of a dorsal fin. The flippers and tail are thin and large in relation to the body size, which is about 2-2.2 meters in males and 2.4–2.6 m in females. The oldest recorded animal was a 28-year-old male, 199 cm in length.[15] Mature females are larger than males. Sexual dimorphism is expressed after females reach about 150 cm (59 in); the female rostrum continues to grow after the male rostrum stops growing, eventually reaching approximately 20 cm (7.9 in) longer.

Biology

Life cycle

Births may take place year round, but appear to be concentrated between December to January and March to May.[16] Females gestate on average once every two years; gestation is thought to be approximately 9–10 months. After around one year, juveniles are weaned and they reach sexual maturity at about 10 years of age.[17] During the monsoon, South Asian river dolphins tend to migrate to tributaries of the main river systems.[16] Occasionally, individuals swim along with their beaks emerging from the water,[18] and they may "breach"; jumping partly or completely clear of the water and landing on their sides.[18]

Diet

South Asian river dolphins rely on echolocation to find prey due to their poor eyesight. Their extended rostrum is advantageous in detecting hidden or hard-to-find prey items. The prey is held in their jaws and swallowed. Their teeth are used as a clamp rather than a chewing mechanism.[19]

The species feeds on a variety of shrimp and fish, including carp and catfish. The Ganges subspecies may take birds and turtles. They are usually encountered on their own or in loose aggregations; the dolphins do not form tight interacting groups.[20][19]

Vision

The species lacks a crystalline eye lens and has evolved a flat cornea. The combination of these traits makes the eye incapable of forming clear images on the retina and renders the dolphin effectively blind, but the eye may still serve as a light receptor. The retina contains a densely packed receptor layer, a very thin bipolar and ganglion cell layer, and a tiny optic nerve (with only a few hundred optic fibers) that are sufficient for the retina to act as a light-gathering component.[21] Although its eye lacks a lens (this species is also referred to as the "blind dolphin"), the dolphin still uses its eye to locate itself. The species has a slit similar to a blowhole on the top of the head, which acts as a nostril.[22]

The dense pigmentation in the skin overlying the eye prevents light from reaching the retina from any entrance except for a pinhole sphincter-like structure. This structure is controlled by a cone-shaped muscle layer that extends from the posterior eye orbit to the overlying eye skin layer. The sphincter-like structure is capable of sensing light and may be able to sense the direction from where the light was emitted. However, the muddy waters, or low light conditions, that P. gangetica inhabits negate the use of the little vision that remains.[21]

Vocalization

The Ganges subspecies shows object-avoidance behavior in both the consistently heavily murky waters of its habitat and in clear water in captivity, suggesting it is capable of using echolocation effectively to navigate and forage for prey.[21] However, information is limited on how extensively vocalization is used between individuals. This subspecies of river dolphin is capable of performing whistles, but rarely does so, suggesting that the whistle is a spontaneous sound and not a form of communication. The Ganges river dolphin most typically makes echolocation sounds such as clicks, bursts, and twitters.[23] Produced pulse trains are similar in wave form and frequency to the echolocation patterns of the Amazon river dolphin. Both species regularly produce frequencies lower than 15 kHz and the maximum frequency is thought to fall between 15 and 60 kHz.[21]

Echolocation is also used for population counts by using acoustic surveying. This method is still being developed and is not heavily used due to cost and technical skill requirement.[24] Given the dolphin's blindness, it produces an ultrasonic sound that is echoed off other fish and water species, allowing it to identify prey.[25]

Distribution and habitat

The South Asian river dolphins are native to the freshwater river systems located in Nepal, India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.[2] They can be most commonly found in water with high abundance of prey and reduced flow.[13] They migrate seasonally—downstream in colder conditions with lower water levels and upstream in warmer conditions with higher water levels.[26]

The Ganges subspecies (P. g. gangetica) can be found along the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna and Karnaphuli-Sangu river systems of Bangladesh and India, and the Sapta Koshi and Karnali Rivers in Nepal.[13][27] A small subpopulation may still be found on the Ghaghara River, but requires verification.

Being a mammal, the Ganges river dolphin cannot breathe in the water and must surface every 30–120 seconds. Because of the sound it produces when breathing, the animal is popularly referred to as the susu.[22] The Ganges river dolphin favours deep pools, eddy countercurrents located downstream of the convergence of rivers and of sharp meanders, and upstream and downstream of midchannel islands.[22][27]

The Indus subspecies (P. g. minor) today only occurs in a 1,000-km stretch of the Indus River itself and several connecting channels between the Jinnah and Kotri barrages.[28] In the past, it was to be found along 3,400 km of the Indus, its tributaries, and neighboring river systems. Its range has contracted by about 80% since 1870.[29] Since the two originally inhabited river systems – between the Sukkur and Guddu barrage in Pakistan's Sind Province, and in the Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Provinces – are not connected in any way, how they were colonized remains unknown. The river dolphins are unlikely to have travelled from one river to another through the sea route, since the two estuaries are very far apart. A possible explanation is that several north Indian rivers such as the Sutlej and Yamuna changed their channels in ancient times while retaining their dolphin populations.[30]

Conservation

A 2017 population assessment estimated less than 5,000 individuals for the species as a whole, of which about 3,500 belong to the Ganges subspecies and about 1,500 to the Indus subspecies.[31] However, the underlying surveys are temporally patchy and believed to contain uncertainty. Current population trends are unclear. A demonstrable increase in the main river population of the Indus subspecies between 1974 and 2008 may have been driven by permanent immigration from upstream tributaries, where the species no longer occurs.[2]

International trade is prohibited by the listing of the South Asian river dolphin on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.[32] It is protected under the Indian Wildlife Act, although these legislations require stricter enforcement.[16] Both subspecies are listed by the IUCN as endangered on their Red List of Threatened Species.[2] The Indus river dolphin is listed as endangered by the US government National Marine Fisheries Service under the Endangered Species Act.

The species is listed on Appendix I[33] and Appendix II[33] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals.

The Ministry of Environment and Forest declared the Gangetic dolphin the national aquatic animal of India. A stretch of the Ganges River between Sultanganj and Kahlgaon in Bihar has been declared a dolphin sanctuary and named Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary, the first such protected area.

The Uttar Pradesh government in India is propagating ancient Hindu texts in hopes of raising the community support to save the dolphins from disappearing. One of the lines being versed from Valimiki's Ramayan, highlighted the force by which the Ganges emerged from Lord Shivji's locks and along with this force came many species such as animals, fish, and the Shishumaar—the dolphin.[34]

On 31 December 2020, a dead adult dolphin was found at the Sharda canal in the Pratapgarh district in India. A video circulated on social media showing a dozen men beating the dolphin with sticks and an ax. On 7 January 2021, three people were arrested.[35]

Human interaction

Both subspecies have been adversely affected by human use of river systems in South Asia. Entanglement in fishing nets as bycatch can cause significant damage to local populations, and individuals are taken each year by hunters; their oil and meat are used as a liniment, as an aphrodisiac, and as bait for catfish. Poisoning of the water supply from industrial and agricultural chemicals may have also be a contributing factor towards population decline, as these chemicals are biomagnified in the bodies of the dolphins.[36] Perhaps the most significant issue is the building of more than 50 dams along many rivers, causing the segregation of populations and a narrowed gene pool in which dolphins can breed.[29] An immediate danger for the Ganges subspecies in National Chambal Sanctuary is the decrease in river depth and appearance of sand bars dividing the river course into smaller segments, as irrigation has lowered water levels throughout their range.[37]

Nonhuman personhood

On 20 May 2013, India's Ministry of Environment and Forests declared dolphins ‘nonhuman persons’ and as such has forbidden their captivity for entertainment purposes; keeping dolphins in captivity must satisfy certain legal prerequisites.[38]

Project Dolphin

On the occasion of the 74th Independence Day, 15 August 2020, the Indian Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change announced 'Project Dolphin' to boost conservation of both river and oceanic dolphins.[39]

References

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file ""Ganges river dolphin"" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

- "Platanista Wagler 1830 (toothed whale)". Fossilworks.

- Smith, B.D. & Braulik, G.T. (2017). "Platanista gangetica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T41758A50383612.

- Indus river dolphin. worldwildlife.org

- "Declaration of Gangetic Dolphin as National Aquatic Animal" (PDF). Government of India – Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- "Gangetic river dolphin to be city animal of Guwahati". The Times of India. 6 June 2016.

- "The Official Web Gateway to Pakistan". pakistan.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Kinze, C.C. (2000). "Rehabilitation of Platanista gangetica (Lebeck, 1801) as the valid scientific name of the Ganges dolphin". Zoologische Mededelingen. National Museum of Natural History. 74: 193–203.

- Pilleri, G.; G. Marcuzzi & O. Pilleri (1982). "Speciation in the Platanistoidea, systematic, zoogeographical and ecological observations on recent species". Investigations on Cetacea. 14: 15–46.

- Braulik, G. T.; Barnett, R.; Odon, V.; Islas-Villanueva, V.; Hoelzel, A. R.; Graves, J. A. (2015). "One Species or Two? Vicariance, Lineage Divergence and Low mtDNA Diversity in Geographically Isolated Populations of South Asian River Dolphin". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 22 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9265-6. S2CID 14113756.

- Rice, DW (1998). Marine mammals of the world: Systematics and distribution. Society for Marine Mammalogy. ISBN 978-1-891276-03-3.

- "Susu, the blind purpoise ... in the Ganges River, blind porpoise of Asia". The New Book of Knowledge, Grolier Incorporated. 1977., page 451 [letter A] and page 568 [letter S].

- Braulik, G. T.; Barnett, R.; Odon, V.; Islas-Villanueva, V.; Hoelzel, A. R.; Graves, J. A. (2014). "One Species or Two? Vicariance, Lineage Divergence and Low mtDNA Diversity in Geographically Isolated Populations of South Asian River Dolphin". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 22 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9265-6. S2CID 14113756.

- "South Asian river dolphin (Platanista gangetica)". EDGE. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Herald, E. S.; Brownell Jr, R. L.; Frye, F. L.; Morris, E. J.; Evans, W. E.; Scott, A. B. (12 December 1969). "Blind River Dolphin: First Side-Swimming Cetacean". Science. New Series. 166 (3911): 1408–1410. Bibcode:1969Sci...166.1408H. doi:10.1126/science.166.3911.1408. PMID 5350341. S2CID 5670792.

- Kasuya, T. (1972). "Some information on the growth of the Ganges dolphin with a comment on the Indus dolphin" (PDF). Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst. 24: 87–108.

- Boris Culik. "Platanista gangetica (Roxburgh, 1801)". CMS Report. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- Swinton, J.; W. Gomez & P. Myer. "Platanista gangetica". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society". Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "Ganges River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica gangetica)". Dolphins-World. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Indus River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica minor)". Dolphins-World. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Herald, Earl S.; Brownell, Robert L.; Frye, Fredric L.; Morris, Elkan J.; Evans, William E.; Scott, Alan B. (1969). "Blind River Dolphin: First Side-Swimming Cetacean". Science. 166 (3911): 1408–1410. Bibcode:1969Sci...166.1408H. doi:10.1126/science.166.3911.1408. JSTOR 1727285. PMID 5350341. S2CID 5670792.

- "Ganges River dolphin". WWF. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Mizue, Kazuhiro; Takemura, Akira; Nishiwaki, Masaharu (1971). "The Underwater Sound of Ganges River Dolphins (Platanista gangetica)" (PDF). The Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute. 23: 123–128 – via ICR.

- Richman, Nadia I.; Gibbons, James M.; Turvey, Samuel T.; Akamatsu, Tomonari; Ahmed, Benazir; Mahabub, Emile; Smith, Brian D.; Jones, Julia P. G. (7 May 2014). "To See or Not to See: Investigating Detectability of Ganges River Dolphins Using a Combined Visual-Acoustic Survey". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e96811. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...996811R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096811. PMC 4013050. PMID 24805782.

- Koshy, Jacob (1 September 2016). "It is pollution that made Gangetic dolphins 'blind', says Uma Bharti". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Sinha, R. K.; Kannan, K. (2014). "Ganges River Dolphin: An Overview of Biology, Ecology, and Conservation Status in India". Ambio. 43 (8): 1029–1046. doi:10.1007/s13280-014-0534-7. PMC 4235892. PMID 24924188.

- Paudel, S.; Pal, P.; Cove, MV; Jnawali, S.R.; Abel, G.; Koprowski, J.L.; Ranabhat, R. (2015). "The Endangered Ganges River dolphin Platanista gangetica gangetica in Nepal: abundance, habitat and conservation threats". Endangered Species Research. 29 (1): 59–68. doi:10.3354/esr00702.

- "Indus River Dolphin". WWF Pakistan.

- Braulik, G. T. (2006). "Status assessment of the Indus river dolphin, Platanista minor minor, March–April 2001". Biological Conservation. 129: 579–590. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.11.026.

- Sanyal, S. (2012). Land of the Seven Rivers: A Brief History of India's Geography. Penguin.

- Braulik, Gill T.; Noureen, Uzma; Arshad, Masood; Reeves, Randall R. (2015). "Review of status, threats, and conservation management options for the endangered Indus River blind dolphin". Biological Conservation. 192: 30–41. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.09.008.

- "CITES". CITES. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "Appendix I and Appendix II Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals as amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005, and 2008, effective: 5 March 2009.

- "How Hinduism Continues to Save Dolphins in India". The Chakra News. 29 November 2010.

- Pratap, Rishabh Madhavendra; Fox, Kara (9 January 2021). "Three arrested after endangered Ganges River dolphin beaten to death in India". CNN. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- Kannan, Kurunthachalam (1997). "Sources and Accumulation of Butyltin Compounds in Ganges River Dolphin, Platanista gangetica". Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 11 (3): 223–230. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0739(199703)11:3<223::AID-AOC543>3.0.CO;2-U. S2CID 59579188.

- Singh, L.A.K. & R.K. Sharma (1985). "Gangetic dolphin, Platanista gangetica: Observations on habits and distribution pattern in National Chambal Sanctuary". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. Bombay Natural History Society. 82: 648–653. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2009.

- Gautama, Madhulika (16 June 2014). "Dolphins get their due". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- Prime Minister's Office (2020). "The Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi addressed the Nation from the ramparts of the Red Fort on the 74th Independence Day". Press Information Bureau. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Singh, Vijay (1994). The River Goddess. London. ISBN 978-1-85103-195-5.

Further reading

- Randall R. Reeves; Brent S. Stewart; Phillip J. Clapham; James A. Powell (2002). National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0375411410.

- Blind dolphins need space to breath – The Nation (Pakistan)

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Platanista gangetica. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Platanista gangetica. |

- Mueenuddin, N. (2020). Indus River Dolphins From the Sky (Motion picture). Nyal Mueenuddin Wildlife Films.

- Goddess Ganga and the Gangetic Dolphin at Biodiversity of India

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, South Asian river dolphin: Platanista gangetica

- US National Marine Fisheries Service Indus River Dolphin web page

- ganges river dolphin media from ARKive

- Convention on Migratory Species page on the Ganges River Dolphin

- Walker's Mammals of the World Online – Ganges River Dolphin

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) – species profile for the Ganges River dolphin