Irrawaddy dolphin

The Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) is a euryhaline species of oceanic dolphin found in discontinuous subpopulations near sea coasts and in estuaries and rivers in parts of the Bay of Bengal and Southeast Asia. It closely resembles the Australian snubfin dolphin (of the same genus, Orcaella) and was not described as a separate species until 2005. It has a slate blue to a slate gray color and are a part of genus Orcaella which is also known as snubfin dolphins. Although found in much of the riverine and marine zones of South and Southeast Asia, the only concentrated lagoon populations are found in Chilika Lake in Odisha, India and Songkhla Lake in southern Thailand.[3]

| Irrawaddy dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Irrawaddy dolphin in Cambodia | |

| |

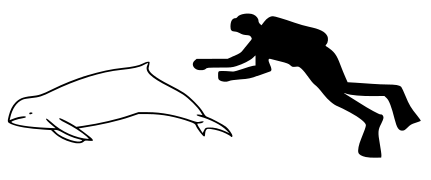

| Size comparison to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Orcaella |

| Species: | O. brevirostris |

| Binomial name | |

| Orcaella brevirostris | |

| |

| Range of genus Orcaella See: Irrawaddy dolphin geographic range map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Taxonomy

One of the earliest recorded descriptions of the Irrawaddy dolphin was by Sir Richard Owen in 1866 based on a specimen found in 1852, in the harbour of Visakhapatnam on the east coast of India.[4] It is one of two species in its genus. It has sometimes been listed variously in a family containing just itself and in the Monodontidae and Delphinapteridae. Widespread agreement now exists to list it in the family Delphinidae.

Etymology and local names

The species name brevirostris comes from the Latin meaning short-beaked. It is very closely related to the Australian snubfin dolphin (Orcaella heinsohni). The two snubfin dolphins were only recognised as separate species in 2005 when a genetic analysis showed that the population found along the coast of northern Australia forms a second species in the genus Orcaella. The Orcaella dolphins are close relatives of the oceanic dolphins in Globicephalinae subfamily.

Vernacular names for the Irrawaddy dolphin include:[5][4][6]

- Thai: โลมาอิรวดี loma irawadi, โลมาหัวบาตร loma hua bat ("alms-bowl dolphin", due to the shape of their heads)

- Odia: ଶିଶୁମାର sisumāra, ଭୁଆସୁଣୀ ମାଛ bhuāsuṇi mācha (lit. oil-yielding dolphin), lagoon area local name- ଖେରା kherā

- Filipino: lampasut

- Bengali: শুশুক shushuko

- Indonesian: pesut mahakum/''ikan pesut

- Khmer: ផ្សោត ph’sout

- Lao: ປາຂ່າ pa’kha

- Malay: empesut

- Burmese: ဧရာဝတီ လင်းပိုင် eyawadi lăbaing

Description

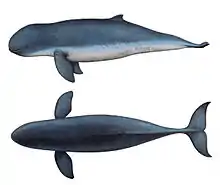

The Irrawaddy dolphin's colour is grey to dark slate blue, paler underneath, without a distinctive pattern. The dorsal fin is small and rounded behind the middle of the back. The forehead is high and rounded; the beak is lacking. The front of its snout is blunt. The flippers are broad and rounded. The finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides) is similar and has no back fin; the humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) is larger, and has a longer beak and a larger dorsal fin.[4] It ranges in weight from 90 to 200 kg (200 to 440 lb) with a length of 2.3 m (7.5 ft) at full maturity.[7] Maximum recorded length is 2.75 m (9.0 ft) of a male in Thailand.[5]

The Irrawaddy dolphin is similar to the beluga in appearance, though most closely related to the killer whale. It has a large melon and a blunt, rounded head, and the beak is indistinct. Its dorsal fin, located about two-thirds posterior along the back, is short, blunt, and triangular. The flippers are long and broad. It is lightly colored all over, but slightly more white on the underside than the back. Unlike any other dolphin, the Irrawaddy's U-shaped blowhole is on the left of the midline and opens towards the front of the dolphin. Its short beak appears very different from those of other dolphins, and its mouth is known for having 12-19 peg-like teeth on each side of the jaws.

Behaviour

Communication is carried out with clicks, creaks, and buzzes at a dominant frequency of about 60 kilohertz, which is thought to be used for echolocation. Bony fish and fish eggs, cephalopods, and crustaceans are taken as food. Observations of captive animals indicate food may be taken into the mouth by suction. Irrawaddy dolphins are capable of squirting streams of water that can reach up to 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in); this distinct behaviour has been known for herding fish into a general area for hunting.[8] They do this sometimes while spyhopping and during feeding, apparently to expel water ingested during fish capture or possibly to herd fish. Some Irrawaddy dolphins kept in captivity have been trained to do spyhopping on command. The Irrawaddy dolphin is a slow swimmer, but swimming speeds of 20–25 kilometres per hour (12–16 mph) were reported when dolphins were being chased in a boat.[9]

Irrawaddy dolphins are shy of boats, not known to bow-ride, and generally dive when alarmed. They are relatively slow moving but can sometimes be seen spyhopping and rolling to one side while waving a flipper and occasionally breaching. They are generally found in groups of 2-3 animals, though sometimes as many as 25 individuals have been known to congregate in deep pools. Groups of fewer than six individuals are most common, but sometimes up to 15 dolphins are seen together.[9][10] Traveling and staying in groups not only enables Irrawaddy dolphins to hunt, but it also creates and maintains social bonds and allows copulation to occur.[11]

It surfaces in a rolling fashion and lifts its tail fluke clear of the water only for a deep dive. Deep dive times range from 30 to 150 seconds to 12 minutes. When 277 group dives were timed (time of disappearance of the last dolphin in the group to the emergence of the first dolphin in the group) in Laos, mean duration was 115.3 seconds with a range of 19 seconds to 7.18 minutes.[5]

Interspecific competition has been observed when Irrawaddy dolphins were forced inshore and excluded by more specialized dolphins. When captive humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) and Irrawaddy dolphins were held together, reportedly the Irrawaddy dolphins were frequently chased and confined to a small portion of the tank by the dominant humpbacks. In Chilika Lake, local fishers say when Irrawaddy dolphins and bottlenose dolphins meet in the outer channel, the former get frightened and are forced to return toward the lake.[4]

Mating

A female or male dolphin will attempt to pursue a mate for about a few minutes. They intertwine facing their bellies together and begin to copulate for 40 seconds. Once copulation has occurred, the dolphins will break away from each other and set off in different directions.[11]

Reproduction

These dolphins are thought to reach sexual maturity at seven to nine years. In the Northern Hemisphere, mating is reported from December to June. Its gestation period is 14 months; cows give birth to a single calf every two to three years. Length is about 1 m (3.3 ft) at birth. Birth weight is about 10 kg (22 lb). Weaning is after two years. Lifespan is about 30 years.

Feeding

There are plenty of food items that this dolphin feeds upon. They include fish, crustaceans, and cephalopods. During foraging periods, herds of about 7 dolphins will circle around prey and trap their victim. These prey entrapments occur slightly below the water surface level.[11]

Habitat and subpopulations

Although sometimes called the Irrawaddy river dolphin, it is not a true river dolphin, but an oceanic dolphin that lives in brackish water near coasts, river mouths, and estuaries. It has established subpopulations in freshwater rivers, including the Ganges and the Mekong, as well as the Irrawaddy River from which it takes its name. Its range extends from the Bay of Bengal to New Guinea and the Philippines, although it does not appear to venture off shore. It is often seen in estuaries and bays in Borneo Island, with sightings from Sandakan in Sabah, Malaysia, to most parts of Brunei and Sarawak, Malaysia. A specimen was collected at Mahakam River in East Kalimantan.[1]

Presence of the species in Chinese, Taiwanese, and Hong Kong's waters has been questioned as the reported sightings have been considered unreliable,[12] and the easternmost of ranges along Eurasian continent is in Vietnam.

No range-wide survey has been conducted for this vulnerable species; however, the worldwide population appears to be over 7,000. In India, Irawaddy dolphins are mostly found in Chilika Lake. Known subpopulations of Irrawaddy dolphins are found in eight places, listed here in order of population, including conservation status.

- Bangladesh: 5,832 (VU) in coastal waters of the Bay of Bengal[13] and 451 (VU) in the brackish Sundarbans mangrove forest[14][15]

- India: 156 (VU) in the brackish-water Chilika Lake, Odisha.[16] Presence recorded from Sundarbans National Park, West Bengal also.

- Laos, Cambodia: 78-91 (CR) in a 190-km (118-mi) freshwater stretch of the Mekong River[17]

- Indonesia: ~70 (CR), in a 420-km (260-mi) stretch of the freshwater Mahakam River

- Philippines: ~42 (CR) in the brackish inner Malampaya Sound.[18] Researchers are studying the recent discovery of 30-40 dolphins sighted in the waters of Pulupandan and Bago, Negros Occidental, in Western Visayas.[19]

- Burma: ~58-72 (CR) in a 370-km (230-mi) freshwater stretch of the Ayeyarwady River

- Thailand: less than 50 (CR) in the brackish Songkhla Lake[1]

Interaction with humans

Irrawaddy dolphins have a mutualistic relationship of co-operative fishing with traditional fishers. Fishers in India recall when they would call out to the dolphins, by tapping a wooden key also known as a lahai kway,[20] against the sides of their boats, asking the Irrawaddys to drive fish into their nets.[21] In Burma, in the upper reaches of the Ayeyarwady River, Irrawaddy dolphins drive fish towards fishers using cast nets in response to acoustic signals from them. The fishermen attempt to gain the attention of the dolphins through various efforts such as using a cone-shaped wooden stick to drum the side of their canoes, striking their paddles to the surface of the water, jingling their nets, or making calls that sound turkey-like. A herd of dolphins that agrees to work alongside the fisherman will entrap a school of fish in a semicircle, guiding them towards the boat.[22] In return, the dolphins are rewarded with some of the fishers' bycatch.[23] Historically, Irrawaddy River fishers claimed particular dolphins were associated with individual fishing villages and chased fish into their nets. An 1879 report indicated legal claims were frequently brought into native courts by fishers to recover a share of the fish from the nets of a rival fisher that the plaintiff's dolphin was claimed to have helped fill.[5]

Threats

Irrawaddy dolphins are more susceptible to human conflict than most other dolphins that live farther out in the ocean. Drowning in gillnets is the main threat to them throughout their range. Between 1995 and 2001, 38 deaths were reported and 74% died as a result of entanglement in gillnets with large mesh sizes.[24] The majority of reported dolphin deaths in all subpopulations is due to accidental capture and drowning in gillnets and dragnets, and in the Philippines, bottom-set crabnets. In Burma, electrofishing, gold mining, and dam building are also serious and continuing threats. Though most fishers are sympathetic to the dolphins' plight, abandoning their traditional livelihood is difficult for them.[1]

Another identified threat towards the Irrawaddy dolphins was noise pollution from high-speed vessels. This caused the dolphins to dive significantly longer than usual. The Irrawaddy dolphins always changed directions when they encountered these large vessels.[24]

Laotians and Cambodians have a common belief that the Irrawaddy dolphins are reincarnations of their ancestors. Some even claim that the dolphins have saved drowning villagers and protected people from attacks by crocodiles. Their beliefs and experiences have led the people of Laos and Cambodia to live peacefully alongside one another for ages until recent years, when the technique of using explosives for fishing has emerged. The government of Laos has made use of such tactics illegal, but few regulations have been made in neighboring Cambodia, where explosives are sold in local markets and the practice of using fishnets has been abandoned. The practice of using explosives instead has become very popular and led to a steady decline of populations of fish, and especially the dolphins swimming in the area. Although Laotians may not use explosives, they do use nylon gillnets, which pose another large threat to the survival of the Irrawaddy. Some dolphins accidentally become entangled in the net. Poor fishermen refuse to cut and destroy their nets because it would result in too great of an economic loss to save one Irrawaddy dolphin.[25]

In Laos, a dam across the Mekong River is planned. This could threaten the existence of the endangered Irrawaddy dolphins in downstream Cambodia. Laos's government decision is to forge the dam upstream of the core habitat of the Irrawaddy dolphins. This could precipitate the extinction of this specific species in the Mekong River. The dam builders' proposal is to use explosives to dig out the tons of rock. This will create strong sound waves that could possibly kill the Irrawaddy dolphins due to their highly sensitive hearing structures.[26]

In several Asian countries, Irrawaddy dolphins have been captured and trained to perform in public aquaria. Their charismatic appearance and unique behaviors, including spitting water, spyhopping, and fluke-slapping, make them very popular for shows in dolphinaria. The commercial motivation for using this dolphin species is high because it can live in freshwater tanks and the high cost of marine aquarium systems is avoided. The region within and near the species' range has developed economically; theme parks, casinos, and other entertainment venues that include dolphin shows have increased.

Khmer and Vietnamese fishermen have regarded the Orcaella as a sacred animal. If caught in fishing nets, they release the dolphin from the rest of the catch. In contrast, Khmer-Islam fisherman kill them for food. This has led to the dolphin being reputed to recognize the local languages of the area and approach the Khmer-Islam with caution.[27] In 2002, there were more than 80 dolphinariums in at least nine Asian countries.[28]

Collateral deaths of dolphins due to blast fishing were once common in Vietnam and Thailand. In the past, the most direct threat was killing them for their oil.

The IUCN lists five of the seven subpopulations as endangered, primarily due to drowning in fish nets.[1] For example, the Malampaya population, first discovered and described in 1986, at the time consisted of 77 individuals. Due to anthropogenic activities, this number dwindled to 47 dolphins in 2007.[29] In the Mahakam River in Borneo, 73% of dolphin deaths are related to entanglement in gillnets, due to heavy fishing and boat traffic.[30]

Tourism

The Irrawaddy dolphins in Asia are increasingly threatened by tourist activity, such as large numbers of boats circulating the areas in which they live. The development of tours and boats has put a large strain on the dolphins.[31]

Disease

Cutaneous nodules were found present in various vulnerable populations of Irrawaddy dolphins. A more precise estimate of the affected dolphins is six populations. Although the definite fate of this emergent disease is unknown, the species is at risk.[32]

Conservation

The Irrawaddy dolphin's proximity to developing communities makes the effort for conservation difficult.[33] Entanglement in fishnets and degradation of habitats are the main threats to Irrawaddy dolphins. Conservation efforts are being made at international and national levels to alleviate these threats.

International efforts

Protection from international trade is provided by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Enforcement, though, is the responsibility of individual countries.[1] While some international trade for dolphinarium animals may have occurred, this is unlikely to have ever been a major threat to the species.

Some Irrawaddy dolphin populations are classified by the IUCN as critically endangered; in Lao PDR, Cambodia, Viet Nam (Mekong River sub-population), Indonesia (Mahakam River sub-population, Borneo), Myanmar (Ayeyarwady/Irrawaddy River sub-population), the Philippines (Malampaya Sound sub-population), and Thailand (Songkhla Lake sub-population). Irrawaddy dolphins in general however, are IUCN listed as an Endangered species, which applies throughout their whole range.[1] In 2004, CITES transferred the Irrawaddy dolphin from Appendix II to Appendix I, which forbids all commercial trade in species that are threatened with extinction.[34]

The UNEP-CMS Action Plan for the Conservation of Freshwater Populations of Irrawaddy dolphins notes that multiple-use protected areas will play a key role for conserving freshwater populations. Protected areas in fresh water could be a particularly effective conservation tool and can facilitate management, due to the fidelity of the species to relatively circumscribed areas. The Action Plan provides details on strategies for mitigating by-catch that includes:

- -establishing core conservation areas where gillnetting is banned or severely restricted

- -promoting net attendance rules and providing training on the safe release of entangled dolphins

- -initiating programs to compensate fishers for damage caused to their nets by entangled dolphins that are safely released

- -providing alternative or diversified employment options for gillnet fishers

- -encouraging the use of fishing gear that does not harm dolphins, by altering or establishing fee structures for fishing permits to make gillnetting more expensive while decreasing the fees for nondestructive gear

- -experimenting with acoustical deterrents and reflective nets.[35]

The Irrawaddy dolphin is listed on both Appendix I and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).[36] It is listed on Appendix I[36] as this species has been categorized as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant proportion of their range and CMS Parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them, as well on Appendix II[36] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organized by tailored agreements.[37]

The species is also covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (MoU).[38]

National efforts

Several national efforts are resulting in the reduction of threats to local Irrawaddy dolphin subpopulations:

Portions of Irrawaddy dolphin habitat in the Sundarbans mangrove forest of Bangladesh are included within 139,700 ha (539 sq mi) of three wildlife sanctuaries, which are part of the Sunderbans World Heritage Site. The Wildlife Conservation Society is working with the Bangladesh Ministry of Environment and Forests to create protected areas for the 6000 remaining dolphins[6][39]

Irrawaddy dolphins are fully protected as an endangered species under Cambodian fishery law.[40] In 2005, The World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF) established the Cambodian Mekong Dolphin Conservation Project with support from government and local communities. The aim is to support the survival of the remaining population through targeted conservation activities, research, and education.[41] In January 2012, the Cambodian Fisheries Administration, the Commission for Conservation and Development of Mekong River Dolphin Eco-tourism Zone, and WWF signed the Kratie Declaration on the Conservation of the Mekong River Irrawaddy Dolphin, an agreement binding them to work together, and setting out a roadmap for dolphin conservation in the Mekong River.[42] On 24 August 2012, the Cambodian government announced that 180-kilometre-long (110 mi) stretch of the Mekong River from eastern Kratie province to the border with Laos has been stated as limit fishing zone which uses floating houses, fishing cages and gill nets are disallowed, but simple fishing is allowed.[43] This area is patrolled by a network of river guards, specifically to protect dolphins. Between January and February 2006, a dozen Irrawaddy dolphins were found dead. The discovery of 10 new baby dolphins on the coast of Cambodia was a relief and gave hope that the endangered Irrawaddy dolphins would make a comeback in population. Since the endangerment was evident, 66 guards have been posted on the coast of Cambodia to protect these dolphins, and only two deaths have been reported since these efforts. To make more efforts to keep these animals from going extinct, the use of fishing nets on the coast of Cambodia is banned, as well.[44]

The Irrawaddy dolphin (under the common name of snubfin dolphin, with the scientific name misspelled as Oreaella brevezastris) is included the Indian Wildlife Protection Act,[45] Schedule I,[46] which bans their killing, transport and sale of products.[6] A major restoration effort to open a new mouth between Chilika Lake and the Bay of Bengal in 2000 was successful in restoring the lake ecology and regulating the salinity gradient in the lake waters, which has resulted in increases in the population of Irrawaddy dolphin due to increase of prey species of fish, prawns, and crabs.[47][48]

A conservation program, entitled Conservation Foundation for the Protection of Rare Aquatic Species of Indonesia, focused on protecting the Irrawaddy dolphin population and their habitat, the Mahakam River. The program not only educates and surveys the public, but also monitors the dolphin population and their habitat. A prime example of this is the establishment of patrols in several villages.[49]

Some major concern for the population in the Mekong River has arisen due to numerous threats. In the 1970s, many Irrawaddy dolphins were slaughtered for oil, and soon after, intensive fishing practices with explosives and gillnets began. As of now, the dolphins are protected in Cambodia and Laos Democratic Republic. Now, both explosive fishing and use of gillnets is restricted in many of the Irrawaddy dolphin's habitats.[17] Canadian conservationist Ian Baird set up the Lao Community Fisheries and Dolphin Protection Project to study the Irrawaddy dolphins in the Laotian part of the Mekong. Part of this project compensated fishers for the loss of nets damaged to free entangled dolphins. This project was expanded to include Cambodia, after the majority of the dolphin population was determined to have been killed or migrated to Laos' southern neighbor.[50] The Si Phan Don Wetlands Project has successfully encouraged river communities to set aside conservation zones and establish laws to regulate how and when fish are caught.[51] In April, after a 200-kg Irrawaddy dolphin was found dead on the coast of Laos, the death toll for Irrawaddy dolphins is now five in 2015. Usually, Irrawaddy dolphins are found dead with bruises and scars on their body, being killed by illegal poaching, but this Irrawaddy dolphin was found dead because of old age. She is the oldest and largest Irrawaddy dolphin researchers have discovered. The dolphin was 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) in length and most likely in her late 20s.[52]

Myanmar's Department of Fisheries took charge in December 2005, and instituted a protected region in a 74 km (46 mi) segment of the Ayeyarwady River between Mingun and Kyaukmyaung and created multiple provisions, as well.[22] Protective measures in the area include mandatory release of entangled dolphins, prohibition of the catching or killing of dolphins and trade in whole or parts of them, and the prohibition of electrofishing and gillnets more than 91 metres (300 ft) long, or spaced less than 180 metres (600 ft) apart.[6] Mercury poisoning and habitat loss from gold-mining dredging operations in the river have been eliminated[53]

In 2000, Malampaya Sound was proclaimed a protected seascape. This is the lowest possible prioritization given to a protected area.[35] Malampaya Sound Ecological Studies Project was initiated by the WWF. With technical support provided by the project, the municipality of Taytay and the Malampaya park management developed fishery policies to minimize the threats to the Irrawaddy dolphin from bycatch capture. Gear studies and gear modification to conserve the dolphin species were implemented. The project was completed in 2007.[54] In 2007, the Coral Triangle Initiative, a new multilateral partnership to help safeguard the marine and coastal resources of the Coral Triangle, including the Irrawaddy dolphin subpopulation in Malampaya Sound, was launched.[55][56] In 2006, a new population was discovered in Guimaras island in the Visayas. In 2015, another new population was discovered in Bago in Negros Occidental, part of Negros island in the Visayas.[57]

In 2002, the Marine and Coastal Resources Department was assigned to protect rare aquatic animals such as dolphins, whales, and turtles in Thai territorial waters. To protect the dolphins, patrol vessels ensure boats stay at least 30 m (98 ft) away from dolphins and no chasing of or running through schools of dolphins occurs. Many fishermen on the Bang Pakong River, Prachinburi Province, have been persuaded by authorities to stop shrimp fishing in a certain area and 30 to 40 fishing boats have been modified so they can offer dolphin sightseeing tours.[58] A total of 65 Irrawaddi dolphins has been found dead along the coast of Trat Province in the past three years.[59] The local fishing industry is blamed for the deaths of the dolphins.[60] In January 2013, over a dozen dead Irrawaddy dolphins were found on the coast of Thailand. These dolphins were said to be dead because of a lack of oxygen. Dolphins are mammals, and unlike other animals that live in the sea, they must come to the surface for air. Many of the dolphins are found dead in the water, and others were washed ashore, said to have been dead for a few days. Also, in the first week of February 2013, as many as four Irrawaddy dolphins were found dead.[61]

In 2008, the Department of Forestry and Sarawak Forestry Cooperative in Sarawak established a protected area for Irrawaddy dolphins in Santubong and Damai (Kuching Wetland).[6] Furthermore, they plan to establish more beaches in Miri as protected areas for them. The protection measures in the area include prohibition of catching or killing of dolphins and trade in whole or parts of them, and prohibiting the use of gillnets. The government may also start small- and medium-scale research of this species at Sarawak Malaysia University with sponsorship from Sarawak Shell.

In 2012 in Vietnam, a group of scientists took in four Irrawaddy dolphins and provided them with medical care to see how they would survive. However, they found this to be the first case they saw of Irrawaddy dolphins having bacterial infections. The bacterial infection, chorioamnionitis, is common in many marine animals, but when these few dolphins were taken in, the scientists discovered this same bacterial infection for the first time in this group of dolphins. This disease mostly affects animals that are pregnant because the infection occurs through the umbilical cord and goes into the maternal bloodstream. One of the dolphins was pregnant and before her death was found circling around the bottom of the pool and was found dead early the next morning. This bacterial infection affects many organs in the body of the animal.[62]

See also

References

- Minton, G.; Smith, B. D.; Braulik, G. T.; Kreb, D.; Sutaria, D. & Reeves, R. (2017). "Orcaella brevirostris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T15419A123790805.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Brian D. Smith, William Perrin (March 2007), Conservation Status of Irrawaddy dolphins (Orcaella Brevirostris) (PDF), CMS

- Sinha, R. K. (2004). "The Irrawaddy Dolphins Orcaella of Chilika Lagoon, India" (PDF). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 101 (2): 244–251. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-10.

- Stacey, P. J.; Arnold, P. W. (1999). "Orcaella brevirostris" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 616 (616): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504387. JSTOR 3504387.

- "Proposal for inclusion of species on the appendices of the convention on the conservation of migratory species of wild animals" (PDF). CMS - Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. UNEP/CMS. 2008-08-27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Long, B. "Irrawaddy Dolphin". World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- "Irrawaddy Dolphins, Orcaella brevirostris ~ MarineBio.org." MarineBio Conservation Society. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- "Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris)". Arkive. Wildscreen. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-11-07. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Culik, Boris; Kiel, Germany (2000). "Orcaella brevirostris (Gray, 1866)". Review of Small Cetaceans Distribution, Behaviour, Migration and Threats. UNEP/CMS Convention on Migratory Species. Archived from the original on 2004-12-05. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Ponnampalam, Louisa S.; Hines, Ellen M.; Monanunsap, Somchai; Ilangakoon, Anoukchika D.; Junchompoo, Chalatip; Adulyanukosol, Kanjana; Morse, Laura J. (2013). "Behavioral Observations of Coastal Irrawaddy Dolphins (Orcaella Brevirostris) in Trat Province, Eastern Gulf of Thailand". Aquatic Mammals. 39 (4): 401–408. doi:10.1578/AM.39.4.2013.401.

- https://swfsc.noaa.gov/uploadedFiles/Divisions/PRD/Publications/Zhouetal95(26).pdf

- "Large population of endangered dolphins found in Bangladesh". Agence France-Presse. 2008-10-11. Archived from the original on 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- Smith, Brian D.; Braulik, Gill; Strindberg, Samantha; Benazir, Ahmed; Rubaiyat, Mansur (July 2006). "Abundance of Irrawaddy dolphins (Orcaella brevirostris) and Ganges river dolphins (Platanista Gangetica gangetica) estimated using concurrent counts made by independent teams in waterways of the Sundarbans mangrove forest in Bangladesh". Marine Mammal Science. 22 (3): 527–547. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00041.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- "Study: Bangladesh hosts 6,000 rare dolphins". PR-Inside.com (Press release). Associated Press. 2009-04-01. Archived from the original on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- "Dolphin population in Odisha's Chilika Lake rises to 156". The Financial Express. 2021-01-16. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- Ryan, Gerard Edward; Dove, Verné; Trujillo, Fernando; Doherty, Paul F. (May 2011). "Irrawaddy dolphin demography in the Mekong River: An application of mark-resight models". Ecosphere. 2 (5): art58. doi:10.1890/ES10-00171.1. ISSN 2150-8925.

- Rosero, Earl Victor L. (2012-02-20). "Only 42 left of endangered Irrawaddy dolphins in northern Palawan". GMA News.

- "Rare dolphins make Negros coastal waters their home". GMA News. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Koss, Melissa. "Orcaella Brevirostris." Animaldiversity.umich.edu. Animal Diversity Web, n.d. Web. Retrieved 2014-10-19

- D'Lima, Coralie (2008). "Dolphin-human interactions, Chilika" (PDF). Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- Smith, Brian D.; Tunb, Mya Than; Chita, Aung Myo; Winb, Han; Moeb, Thida (May 2009). "Catch Composition and Conservation Management of a Human–Dolphin Cooperative Cast-Net Fishery in the Ayeyarwady River, Myanmar". Biological Conservation. 142 (5): 1042–1049. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2009.01.015.

- Tun, Tint (2008). "Castnet Fishing with the Help of Irrawaddy Dolphins". Irrawaddy Dolphin. Yangon, Myanmar. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- Kreb, Daniëlle; Budiono, null (2005-04-01). "Conservation management of small core areas: key to survival of a Critically Endangered population of Irrawaddy river dolphins Orcaella brevirostris in Indonesia". Oryx. 39 (2): 178–188. doi:10.1017/S0030605305000426. ISSN 1365-3008.

- Baird, Ian (Fall 1992). "New Campaign To Save Dolphins In Laos". Earth Island Journal. Vol. 7 no. 4. Earth Island Institute. p. 7. ISSN 1041-0406.

- http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?sid=ea3b7b96-709f-4233-b5d0-ed1728842607%2540sessionmgr4005&vid=4&hid=4202&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%253d#db=pwh&AN=6E84043988717

- Marsh H, Lloze R, Heinsohn GE, Kasuya T (1989). Irrawaddy dolphin - Orcaella brevirostris (Gray, 1866) In: Ridgway SH, Harrison SR (eds.) Handbook of marine mammals. Vol. 4: River dolphins and the larger toothed whales. Academic Press, London, pp. 101-118.

- "Irrawaddy Dolphins Gain Trade Protection Under CITES; WWF Urges Countries to Stop All Live Captures". World Wildlife Fund (Press release). 2004-10-08. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- Yan, Gregg (2007-03-08). "Rare Palawan dolphins now down to 47 - WWF". Philippine Daily Inquirer. pp. A1, A6. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- Kreb D, Budiono (2005). Conservation management of small core areas: key to survival of a Critically Endangered population of Irrawaddy river dolphins Orcaella brevirostris in Indonesia. Oryx 39: 178-188.

- Dash, Jatindra (2008-03-02). "Tourism threatens rare Irrawaddy dolphins". Thainidian News. Indo-Asian News Service. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- "Web of Science [v.5.19] - All Databases Full Record". apps.webofknowledge.com. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- Beasley, I.; Pollock, K.; Jefferson, T. A.; Arnold, P.; Morse, L.; Yim, S.; Lor Kim, S.; Marsh, H. (July 2013). "Likely future extirpation of another Asian river dolphin: The critically endangered population of the Irrawaddy dolphin in the Mekong River is small and declining". Marine Mammal Science. 29 (3): E226–E252. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2012.00614.x. ISSN 1748-7692.

- "CITES takes action to promote sustainable wildlife" (Press release). Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). 2004-10-14. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- Smith, Brian D. (2007-03-14). Submitted by William Perrin. "Conservation status of Irrawaddy Dolphins" (PDF). Convention on the Conservation Migratory Species of Wild Animals. Bonn, Germany: CMS/UNEP. 14th Meeting of the CMS Scientific Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-18.

- "Appendix I and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS)" (PDF). CMS - Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. UNEP/CMS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-11.

- "Convention on Migratory Species page on the Irrawaddy Dolphin". cms.int. Archived from the original on 2004-12-05. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- "Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region". Pacificcetaceans.org. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- Revkin, Andrew C. (2009-04-02). "Asian Dolphin, Feared Dying, Is Thriving". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- "LAW ON FISHERIES (Unofficial Translation supported by ADB/FAO TA Project on Improving the Regulatory and Management Framework for Inland Fisheries )" (PDF). 2007.

- "Cambodian Mekong Dolphin Conservation". World Wildlife Fund. 2008-10-21. Archived from the original on 2008-05-05. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- "Kratie Declaration Offers Hope for Mekong Dolphins". Animal Welfare Institute. Spring 2012.

- "Cambodia Creates Safe Zones for Mekong Dolphins". Jakarta Globe. Agence France-Presse. 2012-08-24. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- "Log in to NewsBank". infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- Parliament of India. The Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (Substituted by Act 44 of 1991 ed.). Ministry of Environment and Forests.

- The Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. "Schedule I" (PDF). 33-A. Snubfin Dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris). Part I Mammals.

- "The return of the Irrawaddy dolphin". The Hindu. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- Conservation International (2007-03-15). "Integrating Biodiversity and Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at the Landscape Scale" (PDF). USAID.

- "Scopus - Welcome to Scopus". scopus.com. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- Pandawutiyanon, Wiwat (2005). "Irrawaddy Dolphins Disappearing from the Mekong". Mekong Currents. IPS Asia-Pacific/Probe Media Foundation. Archived from the original on 2010-09-05. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- Cranmer, Jeff; Steven Martin; Kirby Coxon (2002). "The Far South". The Rough Guide to Laos. Rough Guides. p. 309. ISBN 9781858289052.

- http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=6&sid=9f065f13-9bb4-4c56-ae75-b24d328ff041%2540sessionmgr4002&hid=4111&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%253d#AN=G90EPPP20150406.00011&db=pwh

- "Site Of Human-dolphin Partnership Becomes Protected Area". Science Daily. ScienceDaily LLC. 2006-06-23. pp. Science News. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- "Malampaya Sound Ecological Studies Project". WWF Philippines. 2008-07-07. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- Philippine information Agency (2008-06-22). "PGMA to push for sustainable management of Coral Triangle" (Press release). Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- Hamann, Mark; Heupel, Michelle; Lukoschek, Vimoksalehi; Marsh, Helene (2008-05-11). "Incorporating information about marine species of conservation concern and their habitats into a network of MPAs for the Coral Triangle region (Draft)". ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. Archived from the original (DOC) on 2009-10-01.

- "Rare dolphins make Negros coastal waters their home". gmanetwork.com.

- Svasti, Pichaya (2007-03-24). "The Irrawaddy dolphin; It's an uphill struggle, but Thailand is trying to protect its marine wildlife". Bangkok Post – via Factiva.

It wasn't until 2002 that the Marine and Coastal Resources Department was assigned to protect rare aquatic animals such as dolphins, whales and turtles in Thai territorial waters. To protect the dolphins, patrol vessels will ensure that boats stay at least 30 metres away from dolphins and that there is no chasing of or running through schools of dolphins ... Thanks to persuasion by the authorities, many fishermen on the Bang Pakong have agreed to stop using the phong phang, and 30 to 40 fishing boats have been modified so they can offer dolphin sightseeing tours ... But shrimp boats from other provinces are still fishing the Bang Pakong."

- "65 dolphins found dead in three years". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2014-01-24 – via NewspaperDirect.

- "Fishery blamed for dolphin deaths". Bangkok Post. 2013-02-23. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- Tumcharoen, Surasak (2013-02-07). "Dozen Irrawaddy dolphins found dead off Thailand's eastern coast". Xinhuanet. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 2013-02-11. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- Yu, Jin Hai; Xia, Zhao Fei (2013-03-01). "Bacterial infection in an irrawaddy dolphin (orcaella brevirostris)". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 44 (1): 156–158. doi:10.1638/1042-7260-44.1.156. ISSN 1042-7260. PMID 23505717. S2CID 22163089.

Bibliography

External links

- Video of Irrawaddy dolphin behavior

- WWF-US Irrawaddy dolphin page

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society

- Transcript of briefing by Burmese marine biologist Tint Tun describes human/dolphin cooperative fishing

- Worldwide Bycatch of Cetaceans, National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-OPR-36 July 2007 65 Irrawaddy dolphin mentions

- Dolphin World Irrawaddy Dolphin

- WDC About Irrawaddy Dolphin

- Photos of Irrawaddy dolphin on Sealife Collection