Antarctic minke whale

The Antarctic minke whale or southern minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) is a species of minke whale within the suborder of baleen whales. It is the second smallest rorqual after the common minke whale and the third smallest baleen whale. Although first scientifically described in the mid-19th century, it was not recognized as a distinct species until the 1990s. Once ignored by the whaling industry due to its small size and low oil yield, the Antarctic minke was able to avoid the fate of other baleen whales and maintained a large population into the 21st century, numbering in the hundreds of thousands.[4] Surviving to become the most abundant baleen whale in the world, it is now one of the mainstays of the industry alongside its cosmopolitan counterpart the common minke. It is primarily restricted to the Southern Hemisphere (although vagrants have been reported in the North Atlantic) and feeds mainly on euphausiids.

| Antarctic minke whale [1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Antarctic minke whale in Ross Sea | |

| |

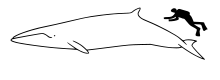

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Balaenopteridae |

| Genus: | Balaenoptera |

| Species complex: | minke whale species complex |

| Species: | B. bonaerensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Balaenoptera bonaerensis Burmeister, 1867 | |

| |

| Antarctic minke whale range | |

Taxonomy

History

In February 1867, a fisherman found an estimated 9.75 m (32.0 ft) male rorqual floating in the Río de la Plata near Belgrano, about ten miles from Buenos Aires, Argentina. After bringing it ashore he brought it to the attention of the German Argentine zoologist Hermann Burmeister, who described it as a new species, Balaenoptera bonaerensis, the same year.[5] The skeleton of another specimen, a 4.7 m (15 ft) individual taken off Otago Head, South Island, New Zealand, in October 1873, was sent by Professor Frederick Hutton, keeper of the Otago Museum in Dunedin, to the British Museum in London, where it was examined by the British zoologist John Edward Gray, who described it as a new species of "pike whale" (minke whale, B. acutorostrata) and named it B. huttoni.[6][7] Both descriptions were largely ignored for a century.

Gordon R. Williamson was the first to describe a dark-flippered form in the Southern Hemisphere, based on three specimens, a pregnant female taken in 1955 and two males taken in 1957, all brought aboard the British factory ship Balaena. All three had uniformly pale gray flippers and bicolored baleen, with white plates in the front and gray plates in the back.[8] Further studies in the 1960s supported his description.[9] In the 1970s osteological and morphological studies suggested it was at least a subspecies of the common minke whale, which was designated B. a. bonaerensis, after Burmeister's specimen.[10][11] In the 1980s further studies based on external appearance and osteology suggested there were in fact two forms in the Southern Hemisphere, a larger form with dark flippers and a "diminutive" or "dwarf form" with white flippers, the latter of which appeared to be more closely related to the common form of the Northern Hemisphere.[12][13] This was strengthened by genetic studies using allozyme and mitochondrial DNA analyses, which proposed there were at least two species of minke whale, B. acutorostrata and B. bonaerensis, with the dwarf form being more closely related to the former species.[14][15][16][17] One study, in fact, suggested that sei whales and the offshore form of Bryde's whale were more closely related to one another than either species of minke whale were to each other.[14] The American scientist Dale W. Rice supported these conclusions in his seminal work on marine mammal taxonomy, giving what he called the "Antarctic minke whale" (B. bonaerensis, Burmeister, 1867), full specific status[18] – this was followed by the International Whaling Commission a few years later. Other organizations followed suit.

Divergence

Antarctic and common minke whales diverged from each other in the Southern Hemisphere 4.7 million years ago, during a prolonged period of global warming in the early Pliocene which disrupted the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and created local pockets of upwelling, facilitating speciation by fragmenting populations.[19]

Hybrids

There have been two confirmed hybrids between Antarctic and common minke whales. Both were caught in the northeastern North Atlantic by Norwegian whaling vessels. The first, an 8.25 m (27.1 ft) female taken off western Spitsbergen (78°02′N 11°43′E) on 20 June 2007, was the result of a pairing between a female Antarctic minke and a male common minke. The second, a pregnant female taken off northwestern Spitsbergen (79°45′N 9°32′E) on 1 July 2010, on the other hand, had a common minke mother and an Antarctic minke father. Her female fetus, in turn, was fathered by a North Atlantic common minke, demonstrating that back-crossing is possible between hybrids of the two species.[20][21]

Description

Size

The Antarctic minke is among the smallest of the baleen whales, with only the common minke and the pygmy right whale being smaller. The longest caught off Brazil were an 11.9 metres (39.0 feet) female taken in 1969 and an 11.27 metres (37.0 feet) male taken in 1975, the former four feet longer than the second longest females and the latter five feet longer than the second longest males.[22] Off South Africa, the longest measured were a 10.66 metres (35.0 feet) female and a 9.75 metres (32.0 feet) male.[23] The heaviest caught in the Antarctic were a 9 metres (29.5 feet) female that weighed 10.4 metric tons (11.5 short tons)[24] and an 8.4 metres (27.6 feet) male that weighed 8.8 metric tons (9.7 short tons).[25] At physical maturity, females average 8.9 metres (29.2 feet) and males 8.6 metres (28.2 feet). At sexual maturity, females average 7.59 metres (24.9 feet) and males 8.11 metres (26.6 feet). Calves are estimated to be 2.74 metres (9 feet) at birth.[23]

External appearance

_13.jpg.webp)

Like their close relative the common minke, the Antarctic minke whale is robust for its genus. They have a narrow, pointed, triangular rostrum with a low splashguard. Their prominent, upright, falcate dorsal fin – often more curved and pointed than in common minkes –is set about two-thirds the way along the back. About half of individuals have a light gray flare or patch on the posterior half of the dorsal fin, similar to that seen in species of dolphins in the genus Lagenorhynchus. They are dark gray dorsally and clean white ventrally. The lower jaw projects beyond the upper jaw and is dark gray on both sides.[26] Antarctic minkes lack the light gray rostral saddle present in the common and dwarf forms.[27] All individuals possess pale, thin blowhole streaks trailing from the blowhole slits, which first veer left and then right – particularly the right streak. These streaks appear to be more prominent and consistent on this species than on either the common or dwarf minke. Most also have a variably colored – light gray, light gray with dark edges, or simply dark – ear streak trailing behind the opening for the auditory meatus, which widens and becomes more diffuse posteriorly. A light gray variably shaped double chevron or W-shaped pattern (analogous to a similar pattern seen on their larger cousin the fin whale)[27] lies between the flippers. This broadens to form a light gray shoulder patch above the flippers. Like common and dwarf minkes, they have two light gray to whitish swaths, called the thorax and flank patches, the former running diagonally up from the axilla and diagonally down again to form a triangular intrusion into the dark gray of the thorax and the latter rising more vertically along its anterior edge and extending further dorsally before gradually sloping posteriorly to merge with the white of the ventral side of the caudal peduncle. A dark gray, roughly triangular thorax field separates the two, while a narrower dark gray shoulder infill separates the thorax patch from the shoulder patch. Two light gray, forward directed caudal chevrons extend from the dark gray field above, forming a whitish peduncle blaze between them. The smooth sided flukes, usually about 2.6 to 2.73 m (8.5 to 9.0 ft) wide, are dark gray dorsally and clean white (occasionally light gray to gray) ventrally with a thin, dusky margin. Some small, dark gray speckling may be present on the body.[12][28]

Antarctic minkes lack the bright white, transverse flipper band of the common minke and the white shoulder blaze and bright white flipper patch (occupying the proximal two-thirds of the flipper) of the dwarf minke. Instead, their narrow, pointed flippers, about one-sixth to one-eighth of the total body length, are normally either a plain light gray with an almost white leading edge and a darker gray trailing edge or two-toned, with a thin light gray or dark band separating the darker gray of the proximal third of the flipper from the lighter gray of the distal two-thirds. Unlike the dwarf minke, the dark gray between the eye and flipper does not extend unto the ventral grooves of the throat to form a dark throat patch; there is instead an irregularly shaped line running from about the level of the eye to the anterior insertion of the flipper, merging with the light gray of the shoulder patch.[12][13][27][28][29]

The longest baleen plates average 25 to 27 cm (9.8 to 10.6 in) in length and about 12.5 to 13.5 cm (4.9 to 5.3 in) in breadth and number 155 to 415 pairs (average 273). They are two-toned, with a dark gray outer margin on the posterior plates and a white outer margin on the anterior plates – though there may be some rows of dark plates amongst the white plates.[28] There is a degree of asymmetry, with a smaller number of white plates on the left side than on the right (12% on average for the left versus 34% on average for the right). The dark gray border occupies about one third of the width of the plates (ranging from about one-seventh to over half of its width), with the average width being greater on the left side than on the right. In contrast, dwarf minkes have smaller baleen plates of only 20 cm (7.9 in) in length, have a greater number of white plates (over 54%, often 100%) that lack this asymmetrical coloration, and have a narrow dark gray border (when present) of less than 6% of the width of the plate. Antarctic minkes have an average of 42 to 44 thin, narrow ventral grooves (range 32 to 70) that extend to about 48% of the length of the body – well short of the umbilicus.[12][30]

Distribution

Range

Antarctic minke whales occur throughout much of the Southern Hemisphere. In the western South Atlantic, they have been recorded off Brazil from 0°53'N to 27°35'S (nearly year-round),[31][32][33] Uruguay,[31] off central Patagonia in Argentina (November–December),[34] and in the Strait of Magellan and Beagle Channel of southern Chile (February–March),[35] while in the eastern South Atlantic they have been recorded in the Gulf of Guinea off Togo,[36] off Angola,[37] Namibia (February),[38][39] and Cape Province, South Africa.[23] In the Indian and Pacific Oceans, they have been recorded off Natal Province, South Africa,[23] Réunion (July),[40] Australia (July–August),[13] New Zealand, New Caledonia (June),[41] Ecuador (2°S, October),[42] Peru (12°30'S, September–October),[43] and the northern fjords of southern Chile.[44] Vagrants have been reported in Suriname – an 8.2 metres (26.9 feet) female was killed 45 km (28 mi) upstream the Coppename River in October 1963;[45] the Gulf of Mexico, where a 7.7 metres (25.3 feet) female was found dead off the U.S. state of Louisiana in February 2013;[46] and off Jan Mayen (June) in the northeastern North Atlantic.[20]

They appear to disperse into offshore waters during the breeding season. In the spring (October–December), Japanese sighting surveys from 1976 to 1987 recorded relatively high encounter rates of minke whales off South Africa and Mozambique (20° – 30°S, 30° – 40°E), off Western Australia (20° – 30°S, 110° – 120°E), around the Gambier Islands of French Polynesia (20° – 30°S, 130° – 140°W), and in the eastern South Pacific (10° – 20°S, 110° – 120°W).[47] Later surveys, which distinguished between Antarctic and dwarf minke whales, showed that most of these were Antarctic minke whales.[3]

They have a circumpolar distribution in the Southern Ocean (where they have been recorded year-round),[48] including the Bellingshausen, Scotia,[49] Weddell and Ross Seas.[50] They are most abundant in the MacKenzie Bay-Prydz Bay area (60° – 80°E, south of 66°S) and relatively numerous off Queen Maud Land (0° – 20°E, 66° – 70°S), in the Davis (80° – 100°E, south of 66°S) and Ross Seas (160°E – 140°W, south of 70°S), and in the southern Weddell Sea (20° – 40°W, south of 70°S).[51] Like their larger cousin the blue whale, they have a particular affinity for the pack ice. In the spring (October–November), they occur widely throughout the pack ice zone to near the edge of the fast ice, where they have been observed between belts of pack ice and in leads and polynyas – often in heavy ice cover.[52] Some individuals have become trapped in the ice and were forced to overwinter in the Antarctic – for example, up to 120 "lesser rorquals" were trapped in a small breathing hole with sixty killer whales and an Arnoux's beaked whale in Prince Gustav Channel, east of the Antarctic Peninsula and west of James Ross Island, in August 1955.[53]

Migration and movements

Two Antarctic minke whales marked with "Discovery tags" – 26 cm (10 in) stainless steel tubes with an inscription and number engraved on them – in the Southern Ocean during the austral summer (January) were recovered a few years later off northeastern Brazil (6° – 7°S, 34°W) during the austral winter (July and September, respectively). The first was marked off Queen Maud Land (69°S 19°E) and the second southeast of the South Orkney Islands (62°S 35°W). Over twenty individuals marked with these Discovery tags showed large-scale movements around the Antarctic continent, each moving more than 30 degrees of longitude – two, in fact, had moved over 100 degrees of longitude. The first was marked off the Adélie Coast (66°S 141°E) and recovered the following season off the Princess Ragnhild Coast (68°S 26°E), a minimum of 114 degrees of longitude. The second was marked north of Cape Adare (68°S 172°E) and recovered nearly six years later northwest of the Riiser-Larsen Peninsula (68°S 32°E), a minimum of over 139 degrees of longitude. Both were marked and recovered in January.[54]

On 20 January 1972, a 49.5 cm (19.5 in) broken-off bill of a marlin (Makaira sp.) was found embedded in the rostrum of a minke whale caught in the Southern Ocean at 64°06′S 87°14′E, providing indirect evidence of migration to the warmer tropical or subtropical waters of the Indian Ocean.[55]

Population

Earlier estimates suggested that there were several hundred thousand minke whales in the Southern Ocean.[4][56] In 2012, the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission agreed upon a best estimate of 515,000. The Report of the Scientific Committee acknowledged that this estimate is subject to some degree of negative bias because some minke whales would have been outside the surveyable ice edge boundaries.[57]

Biology

Natural history

Antarctic minke whales become sexually mature at 5 to 8 years of age for males and 7 to 9 years of age for females. Both become physically mature at about 18 years of age. After a gestation period of about 10 months, a single calf of 2.73 m (9.0 ft) is born – twin and triplet fetuses have been reported, but are rare. After a lactation period of about six months, the calf is weaned at a length of 4.6 m (15 ft). The calving interval is estimated to be about 12.5 to 14 months. Peak calving is from May to June, while peak conception is from August to September. Females may live up to 43 years of age.[23][58][59]

Prey

Antarctic minke whales feed almost exclusively on euphausiids. In the Southern Ocean, over 90% of individuals fed on Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba); E. crystallorophias also formed an important part of the diet in some areas, particularly in the relatively shallow waters of Prydz Bay. Rare and incidental items include calanoid copepods, the pelagic amphipod Themisto gaudichaudii, Antarctic sidestripes (Pleuragramma antarcticum), the crocodile icefish Cryodraco antarcticus, nototheniids, and myctophids.[60][61][62] The majority of individuals examined off South Africa had empty stomachs. The few that did have food in their stomachs had all preyed on euphausiids, mainly Thysanoessa gregaria and E. recurva.[23]

Predation

Antarctic minke whales are the main prey item of Type A killer whales in the Southern Ocean.[63] Their remains have been found in the stomachs of killer whales caught by the Soviets,[64] while individuals caught by the Japanese exhibited damaged flippers with tooth rake scars and parallel scarring on the body suggestive of killer whale attacks.[23] Large groups of killer whales have also been observed chasing, attacking, and even killing Antarctic minke whales.[50][63][65][66] Most attacks involve Type A killer whales, but on one occasion, in January 2009, a group of ten Type B or pack ice killer whales, which normally preyed on Weddell seals in the area by wave-washing them off ice floes, were observed to attack, kill, and feed on a juvenile Antarctic minke whale in Laubeuf Fjord, between Adelaide Island and the Antarctic Peninsula.[67]

Parasites and epibiotics

Little has been published on the parasitic and epibiotic fauna of Antarctic minke whales. Individuals were often found with orange-brown to yellowish patches of the diatom Cocconeis ceticola on their bodies – 35.7% off South Africa and 67.5% in the Antarctic. Of a sample of whales caught by a Japanese expedition along the ice edge, one-fifth was infested with cyamids (those from one whale were identified as Cyamus balaenopterae). Several hundred of these whale lice can be found on a single whale, with an average of 55 per individual – most are found at the end of the ventral grooves and around the umbilicus. The copepod Pennella was found on only one whale. Cestodes were commonly found in the intestines (one example was identified as Tetrabothrius affinis).[23]

Behavior

Group size and composition

Antarctic minke whales are more gregarious than their smaller counterparts, the common and dwarf minke whale. The average group size in the Antarctic was about 2.4 (adjusted downwards for observer bias), with about a quarter of the sightings consisting of singles and one-fifth of pairs; the largest aggregation consisted of 60 individuals.[68] Off South Africa, the average group size was about two, with singles (nearly 46%) and pairs (31%) being the most common – the largest was 15.[23] Off Brazil, most sightings were of singles (32.6%) or pairs (31.5%), with the largest group consisting of 17 individuals.[22]

Like common minke whales, Antarctic minkes exhibit a great deal of spatial and temporal segregation by sex, age class, and reproductive condition. Off South Africa, immature animals predominate from April to May, while mature whales (mainly males) dominate from June onwards – in August and September mature males often accompany cow-calf pairs.[23] Off Brazil, a good proportion of the individuals are immature (particularly for females) in July and August, but by September most are mature, and by October and November nearly all are mature.[30] Females outnumber males two to one off Brazil, while the opposite is true off South Africa, where males outnumber females nearly two to one. Over a quarter of the females off South Africa were found to be lactating, whereas lactating females are very rare in the Antarctic – though a cow-calf pair was observed in the austral winter (August) in the Lazarev Sea.[48] In the sub-Antarctic and Antarctic, immature animals are normally solitary and occur in lower latitudes further offshore, while mature whales are typically found in mixed groups (usually one sex outnumbers the other, and groups composed solely of males or females are occasionally found) and occur in higher latitudes. Mature males dominate in middle latitudes, while mature females predominate in the higher latitudes of the pack ice zone – from two-thirds to three-quarters of the whales in the Ross Sea consist of pregnant females.[24][69][70][71][72][73][74][75]

An immature Antarctic minke whale was observed briefly associating with four dwarf minke whales on the Great Barrier Reef in July 2000.[27]

Unlike common minke whales, they often have a prominent blow, which is particularly visible in the calmer waters near the pack ice.[68] In the narrow holes and cracks in the pack ice they have been observed spyhopping – raising their head vertically – to expose their blowholes to breathe; individuals have even been seen to break breathing holes through sea ice in the winter (July–August), rising in a similar manner.[48][50][52] When traveling fast in open water they can create larger versions of the "roostertail" of spray created by their smaller cousin, the Dall's porpoise.[26] During bouts of feeding they will lunge multiple times onto their side (either left or right) into a dense patch of prey with mouth agape and ventral pleats expanded as their gular pouch fills with prey-laden water. After making a series of shorter dives during which they will surface anywhere from two to fifteen times, they will make a longer dive of up fourteen minutes.[50] Shallower dives of normally less than 40 m (130 ft) are made at night (from about 8 p.m. to about 2 a.m.) while deeper dives that can be over 100 m (330 ft) deep are made during the day (from about 2 a.m. to about 8 p.m.).[76]

Vocalizations

Antarctic minke whales produce a variety of sounds, including whistles, calls reminiscent of a clanging bell, clicks, screeches, grunts, downsweeps,[50] and a sound called bioduck.[76] Downsweeps are intense, low frequency calls that sweep down from about 130 to 115 Hz to about 60 Hz,[77] with a peak frequency of 83 Hz. Each sweep has a duration of 0.2 seconds and an average source level of about 147 decibels at a reference pressure of one micropascal at one metre. The bio-duck call, first described in the 1960s and named by sonar operators on Oberon-class submarines for its purported resemblance to the quack of a duck, consist of a series of anywhere from three to a dozen pulse trains that range from 50 to 200 Hz and have a peak frequency of about 154 Hz – they sometimes also possess harmonics of up to 1 kHz. They are repeated about every 1.5 to 3 seconds and have a source level of 140 decibels at a reference pressure of one micropascal at one metre. Their source remained a mystery for decades until attributed to the Antarctic minke whale in a paper published in 2014 – though it had been suggested to originate from this species as early as the mid-2000s.[78] It has been recorded in the Ross and Lazarev Seas, over Perth Canyon, off Western Australia from late June to early December,[79] and in the King Haakon VII Sea from April to December.[80] The sound seems to be made near the surface before foraging dives, but nothing is known of its function.[76][81]

Whaling

The barque Antarctic, sent by whaling pioneer Svend Foyn and led by Henrik Johan Bull, managed to harpoon at least three minke whales in the Antarctic between December 1894 and January 1895. Two were saved, both being used for fresh meat (one had only yielded two barrels of blubber).[82] In December 1923, when the men of the first modern whaling expedition to visit the Ross Sea saw "a number of spouts" after leaving the ice edge they were soon disgusted to find out that they from lowly minke whales.[83] The few caught by the British in the 1950s were taken more for curiosity than anything else. The chemist Christopher Ash, who had served on the British factory ship Balaena during this time, stated that they were small enough to be lifted by their tails using a 10-ton spring balance and weighed entire. "Generally this is done when there are no other whales about and the deck empty except for a crowd of sightseers," Ash explained, "but this crowd quickly scatters when the whale is just hanging free and starts to spin around and swing from side to side, as it almost always does." Like Bull before him, Ash commented on their meat, which he described as "fine-textured in comparison with the other whales, and if properly cooked almost indistinguishable from beef."[84]

They were primarily exploited for this very reason – their high quality meat – in later years, which fetched as much as two dollars a pound in 1977.[85] With the larger blue, fin, and sei whales depleted, whaling nations focused their attention on the smaller, but more numerous, minke whales. Though the Soviets had caught several hundred in the 1950s, it was not until 1971-72 that a significant catch was made, with over 3,000 being taken (nearly all by a single Japanese expedition).[86] Not wanting to repeat the same mistakes it had made with previous species, the International Whaling Commission set a quota of 5,000 for the following season, 1972-73. Despite these precautions, the quota was exceeded by 745 – later quotas would be as high as 8,000.[87]

During the commercial whaling era, from 1950-51 to 1986-87, 97,866 minke whales (the vast majority probably Antarctic minkes) were caught in the Southern Ocean – mainly by the Japanese and Soviets – with a peak of 7,900 being reached in 1976-77.[88] Harpoon guns of lesser caliber and "cold harpoons" (harpoons without explosive shells) had to be used due to their small size, while no air was pumped into the carcasses when they were tied alongside for towing to ensure the greatest quality of meat.[85][89] While an expedition or two was fitted out each year specifically for minke whales – the Jinyo Maru in 1971-72, the Chiyo Maru from 1972-73 to 1974-75, and the Kyokusei Maru in 1973-74 – most expeditions, which targeted other species, ignored minkes during the peak of the whaling season (November–December and late February to early March) and only caught them on whaling grounds relatively close to those of larger ones – the minke whaling grounds were much further south (south of 60°S) than those for fin and sei whales.[86][90][91]

From 1987 to the present, Japan has been sending a fleet consisting of a single factory ship and several catcher/spotting vessels to the Southern Ocean to catch Antarctic minkes under Article VIII of the IWC, which allows the culling of whales for scientific research. The first research program, Japanese Research Program in the Antarctic (JARPA), began in 1987-88, when 273 Antarctic minkes were caught. The quota and catch soon increased to 330 and 440. In 2005-06, the second research program, JARPA II, began. In its first two years, in what Japan called its "feasibility study", 850 Antarctic minkes, as well as 10 fin whales, were to be taken each season (2005–06 and 2006–07). The quota was reached in the first season, but due to a fire, only 508 Antarctic minkes were caught in the second. In 2007-08, because of constant harassment from environmental groups, they failed to reach the quota again, with a catch of only 551 whales.

Beginning in 1968, larger numbers of minke whales were caught off Natal, South Africa, mainly to supplement the dwindling supply of larger species, particularly the sei whale. A total of 1,113 whales (nearly all Antarctic minke, but a few dwarf minke as well) were caught off the province between 1968 and 1975, with a peak of 199 in 1971. They were taken by whale catchers of 539 to 593 gross tons with 90 mm harpoon guns mounted on their bows, which brought them to the whaling station at Durban (29°53′S 31°03′E) for processing. Gunners refused to take minkes early in the day, because sharks devoured any minke carcasses that were flagged, forcing the catchers to tow them during the chasing of other whales and thus slowing them down. They also could not use asdic, as it frightened them and lead to protracted chases. The season lasted from February to September, with a peak in the last month of the season.[23][92]

In 1966, minke whales became the target of whaling operations off northeastern Brazil (6° – 8°S) due, once again, to the decline of sei whales. Over 14,000 were caught between 1949 and 1985, with a peak of 1,039 in 1975. They were caught by a succession of whale catchers – the 367-ton Koyo Maru 2 (1966–1971), the 306-ton Seiho Maru 2 (1971–1977), and the 395-ton Cabo Branco (also called Katsu Maru 10, 1977–1985) – up to 100 miles offshore and brought to the whaling station at Costinha, operated by the Compania de Pesca Norte do Brasil (COPESBRA) since 1911. The season lasted from June to December, with a peak in either September or October.[30][93][94]

An 8.2 m (27 ft) male Antarctic minke whale (confirmed by genetics) was caught west of Jan Mayen (70°57′N 8°51′W) in the northeastern North Atlantic on 30 June 1996.[20]

Other mortality

Entanglement in fishing gear and probably ship strikes are other sources of mortality. The former have been reported off Peru and Brazil, and the latter off South Australia. All involved calves or juveniles.[31][43][95]

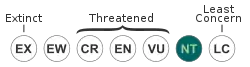

Conservation status

The Antarctic minke whale is currently considered Near Threatened by the IUCN red list. However, the IUCN states that the population size is "clearly in the hundreds of thousands".[3]

The Antarctic minke whale is listed on Appendix II [96] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix II[96] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements.

In addition, the Antarctic minke whale is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region.[97]

References

- Mead, J.G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "Fossil works".

- Cooke, J.G.; Zerbini, A.N.; Taylor, B.L. (2018). "Balaenoptera bonaerensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Branch, T. A. (2006). "Abundance estimates for Antarctic minke whales from three completed circumpolar sets of surveys, 1978/79 to 2003/04". Paper SC/58/IA18 submitted to the International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee, pp. 1-28.

- Burmeister, H. (1867). "Preliminary description of a new species of finner whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis)". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 707-713.

- Gray, J.E. (1874). "On a New-Zealand whale (Physalus antarcticus, Hutton), with notes". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13 (76): 316–318. doi:10.1080/00222937408680867.

- Gray, J.E. (1874). "On the skeleton of the New-Zealand pike whale, Balaenoptera huttoni (Physalus antarcticus, Hutton)". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13 (78): 448–453. doi:10.1080/00222937408680902.

- Williamson, G. R. (1959). "Three unusual rorqual whales from the Antarctic". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 133 (1): 135–144. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1959.tb05556.x.

- Kasuya, T. and T. Ichihara. (1965). "Some informations on minke whales from the Antarctic". Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst., 19: 37-43.

- Omura, H (1975). "Osteological study of the minke whale from the Antarctic". Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute. 27: 1–36.

- Rice, D. W. (1977). "A list of the marine mammals of the world". NOAA Tech. Rep. 711: 1–15.

- Best, P (1985). "External characters of southern minke whales and the existence of a diminutive form". Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute. 36: 1–33.

- Arnold, P.; Marsh, H.; Heinsohn, G. (1987). "The occurrence of two forms of minke whales in east Australian waters with a description of external characters and skeleton of the diminutive or dwarf form". Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute. 38: 1–46.

- Wada, S., and Numachi, K. I. (1991). "Allozyme analyses of genetic differentiation among the populations and species of the Balaenoptera". Genetic ecology of whales and dolphins. Reports of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue 13): 125-154.

- Wada, S., Kobayashi, T., and Numachi, K. I. (1991). "Genetic variability and differentiation of mitochondrial DNA in minke whales". Genetic ecology of whales and dolphins. Reports of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue 13): 203-215.

- Árnason, Ú.; Gullberg, A.; Widegren, B. (1993). "Cetacean mitochondrial DNA control region: sequences of all extant baleen whales and two sperm whale species". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 10 (5): 960–970.

- Pastene, L. A.; Fujise, Y.; Numachi, K. I. (1994). "Differentiation of mitochondrial DNA between ordinary and dwarf forms of southern minke whale". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 44: 277–281.

- Rice, D. W. (1998). "Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution". Society for Marine Mammalogy Special Publication. 4: 1–231.

- Pastene, L. A.; Goto, M.; Kanda, N.; Zerbini, A. N.; Kerem, D. A. N.; Watanabe, K.; Bessho, Y.; Hasegawa, M; Nielsen, R.; Larsen, F.; Palsböll, P. J. (2007). "Radiation and speciation of pelagic organisms during periods of global warming: the case of the common minke whale, Balaenoptera acutorostrata". Molecular Ecology. 16 (7): 1481–1495. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2007.03244.x. PMID 17391271.

- Glover, K. A.; Kanda, N.; Haug, T.; Pastene, L. A.; Øien, N.; Goto, M.; Seliussen, B. B.; Skaug, H. J. (2010). "Migration of Antarctic minke whales to the Arctic". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): 1–6. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515197G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015197. PMC 3008685. PMID 21203557.

- Glover, K. A.; Kanda, N.; Haug, T.; Pastene, L. A.; Øien, N.; Seliussen, B. B.; Sørvik, A. G. E.; Skaug, H. J. (2013). "Hybrids between common and Antarctic minke whales are fertile and can back-cross". BMC Genetics. 14 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-14-25. PMC 3637290. PMID 23586609.

- Da Rocha, J. M.; Braga, N. M. A. (1982). "Brazil Progress Report on cetacean research, June 1980 to May 1981". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 32: 155–159.

- Best, P. B. (1982). "Seasonal abundance, feeding, reproduction, age and growth in minke whales off Durban (with incidental observations from the Antarctic)". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 32: 759–786.

- Fujise, Y.; Ishikawa, H.; Saino, S.; Nagano, M.; Ishii, K.; Kawaguchi, S.; Tanifuji, S.; Kawashima, S.; Miyakoshi, H. (1993). "Cruise report of the 1991/92 Japanese research in Area IV under a special permit for Southern Hemisphere minke whales". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 43: 357–371.

- Lockyer, C (1976). "Body weights of some species of large whales". Journal du Conseil International pour l'Exploration de la Mer. 36 (3): 259–273. doi:10.1093/icesjms/36.3.259.

- Jefferson, Thomas; Marc A. Webber & Robert L. Pitman (2008). Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to their Identification. London: Academic. ISBN 9780123838537. OCLC 272382231.

- Arnold, P. W.; Birtles, R. A.; Dunstan, A.; Lukoschek, V.; Matthews, M. (2005). "Colour patterns of the dwarf minke whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata sensu lato: description, cladistic analysis and taxonomic implications". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 51: 277–307.

- Bushuev, S. G.; Ivashin, M. V. (1986). "Variation of colouration of Antarctic minke whales". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 36: 193–200.

- Wada, S.; Numachi, K. (1979). "External and biochemical characters as an approach to stock identification for the Antarctic minke whale". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 29: 421–32.

- Da Rocha, J (1980). "Progress report on Brazilian minke whaling". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 30: 379–84.

- Zerbini, A. N.; Secchi, E. R.; Siciliano, S.; Simões-Lopes, P. C. (1997). "A review of the occurrence and distribution of whales of the genus Balaenoptera along the Brazilian coast". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 47: 407–417.

- Meirelles, A. C. O.; Furtado-Neto, M. A. A. (2004). "Stranding of an Antarctic minke whale, Balaenoptera bonaerensis (Burmeister, 1867), on the northern coast of South America". Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals. 3 (1): 81–82. doi:10.5597/lajam00052.

- Siciliano, S., Emin-Lima, R., Rodrigues, A.L.F., de Sousa e Silva Jr. J., Scholl, T.G.S. and Moura de Oliveira, J. (2011). "Antarctic minke whales (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) near the Equator". Document SC/63/IA2 submitted to the IWC Scientific Committee's 63rd annual meeting.

- Reyes, L. M. (2006). "Cetaceans of central Patagonia, Argentina". Aquatic Mammals. 32 (1): 20–30. doi:10.1578/am.32.1.2006.20.

- Acevedo, J.; Aguayo-Lobo, A.; Acuna, P.; Pastene, L. A. (2006). "A note on the first record of the dwarf minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) in Chilean waters". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 8 (3): 293–296.

- Segniagbeto, G. H., Van Waerebeek, K., Bouwessidjaou, J. E., Ketoh, K., Kpatcha, T. K., Okoumassou, K., and Ahoedo, K. (2014). "Annotated checklist and fisheries interactions of cetaceans in Togo, with evidence of Antarctic minke whale in the Gulf of Guinea". Integrative Zoology 9 (1): 1-13 (abstract only).

- Weir, C. R. (2010). "A review of cetacean occurrence in West African waters from the Gulf of Guinea to Angola". Mammal Review. 40 (1): 2–39. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2009.00153.x.

- Anonymous (February 21, 2014). "Minke whale saved at Walvis". The Namibian. Archived from the original on June 15, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- Anonymous (February 21, 2014). "Stranded Antarctic minke whale rescued in Walvis Bay". Travel News Namibia. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- Dulau-Drouot, V.; Boucaud, V.; Rota, B. (2008). "Cetacean diversity off La Réunion Island (France)". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK. 88 (6): 1263–1272. doi:10.1017/s0025315408001069.

- Borsa, P (2006). "Marine mammal strandings in the New Caledonia region, Southwest Pacific". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 329 (4): 277–288. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2006.01.004. PMID 16644500.

- Felix, F., and B. Haase. (2013). "Northernmost record of the Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) in the Eastern Pacific". Document SC/65a/IAO2 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee's 65th annual meeting.

- Van Waerebeek, K. and Reyes, J. C. (1994). "A note on the incidental mortality of southern minke whales off western South America". Gillnets and cetaceans. Reports of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue 15): 521-524.

- Viddi, F. A.; Hucke-Gaete, R.; Torres-Florez, J. P.; Ribeiro, S. (2010). "Spatial and seasonal variability in cetacean distribution in the fjords of northern Patagonia, Chile". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 67 (5): 959–970. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsp288.

- Husson, A.M. (1978). The mammals of Suriname. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

- Rosel, P. E., Wilcox, L. A., Monteiro, C., and M. C. Tumlin. (2016). "First record of Antarctic minke whale, Balaenoptera bonaerensis, in the northern Gulf of Mexico". Mar. Bio. Rec. 9:63.

- Kasamatsu, F.; Nishiwaki, S.; Ishikawa, H. (1995). "Breeding areas and southbound migrations of southern minke whales Balaenoptera acutorostrata". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 119: 1–10. doi:10.3354/meps119001.

- Scheidat, M., Bornemann, H., Burkhardt, E., Flores, H., Friedlaender, A., Kock, K. H., Lehnert, L., van Franeker, J. and Williams, R. (2008). "Antarctic sea ice habitat and minke whales". Annual Science Conference in Halifax, 22–26 September, Halifax, Canada.

- Sirovic, A.; Hildebrand, J. A.; Thiele, D. (2006). "Baleen whales in the Scotia Sea during January and February 2003". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 8 (2): 161–171.

- Leatherwood, S.; Thomas, J. A.; Awbrey, F. T. (1981). "Minke whales off northwestern Ross Island". Antarctic Journal. 16: 154–156.

- Kasamatsu, F.; Joyce, G.; Ensor, P.; Mermoz, J. (1996). "Current occurrence of baleen whales in Antarctic waters". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 46: 293–304.

- Ensor, P. H. (1989). "Minke whales in the pack ice zone, East Antarctica, during the period of maximum annual ice extent". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 39: 219–225.

- Taylor, R. J. F. (1957). "An unusual record of three species of whale being restricted to pools in Antarctic sea-ice". In Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 129 (3): 325-331 (abstract only).

- Buckland, S. T. and Duff, E. I. (1989). "Analysis of southern hemisphere minke whale mark-recovery data". Reports of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue 11): 121-143.

- Ohsumi, S (1973). ""Find of a marlin spear from the Antarctic minke whales". Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute". Tokyo. 25: 237–239.

- Branch, T. A.; Butterworth, D. S. (2001). "Southern Hemisphere minke whales: standardized abundance estimates from the 1978/79 to 1997/98 IDCR-SOWER surveys". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 3 (2): 143–174.

- International Whaling Commission. (2013). "Report of the Scientific Committee". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 14 (Supplement): 1-86.

- Masaki, Y (1979). "Yearly change of the biological parameters for the Antarctic minke whale". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 29: 375–95.

- Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins. Facts on File.

- Bushuev, S. G. (1986). "Feeding of minke whales, Balaenoptera acutorostrata, in the Antarctic". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 36: 241–245.

- Bushuev, S. G. (1991). "Distribution and feeding of minke whales in Antarctic Area I". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 41: 303–312.

- Kawamura, A (1994). "A review of baleen whale feeding in the Southern Ocean". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 44: 261–271.

- Pitman, R. L.; Ensor, P. (2003). "Three forms of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Antarctic waters". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 5 (2): 131–139.

- Mikhalev, Y. A.; Ivashin, M. V.; Savusin, V. P.; Zelenaya, F. E. (1981). "The distribution and biology of killer whales in the Southern Hemisphere". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 31: 551–566.

- Jefferson, T. A.; Stacey, P.J.; Baird, R.W. (1991). "A review of killer whale interactions with other marine mammals: predation to co-existence" (PDF). Mammal Review. 21 (4): 151–180. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1991.tb00291.x.

- Ford, J. K.; Reeves, R. R. (2008). "Fight or flight: antipredator strategies of baleen whales". Mammal Review. 38 (1): 50–86. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.573.6671. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2008.00118.x.

- Pitman, R. L.; Durban, J. W. (2012). "Cooperative hunting behavior, prey selectivity and prey handling by pack ice killer whales (Orcinus orca), type B, in Antarctic Peninsula waters". Marine Mammal Science. 28 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00453.x.

- Best, P. B.; Butterworth, D. S. (1980). "Report of the Southern Hemisphere minke whale assessment cruise, 1978/79". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 30: 257–283.

- Kasamatsu, F.; Ohsumi, S. (1981). "Distribution pattern of minke whales in the Antarctic with special reference to the sex ratio in the catch". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 31: 345–348.

- Shimadzu, Y.; Kasamatsu, F. (1983). "Operating pattern of Antarctic minke whaling by the Japanese expedition in 1981/82". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 33: 389–391.

- Shimadzu, Y.; Kasamatsu, F. (1984). "Operating pattern of Antarctic minke whaling by the Japanese expedition in the 1982/83 season". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 34: 357–359.

- Kasamatsu, F; Shimadzu, Y (1985). "Operating pattern of Antarctic minke whaling by the Japanese expedition in the 1983/84 season". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 35: 283–284.

- Kato, H.; Hiroyama, H.; Fujise, Y.; Ono, K. (1989). "Preliminary report of the 1987/88 Japanese feasibility study of the special permit proposal for Southern Hemisphere minke whales". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 39: 235–248.

- Kato, H.; Fujise, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Nakagawa, S.; Ishida, M.; Tanifuji, S. (1990). "Cruise report and preliminary analysis of the 1988/89 Japanese feasibility study of the special permit proposal for southern hemisphere minke whales". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 40: 289–300.

- Kasamatsu, F.; Yamamoto, Y.; Zenitani, R.; Ishikawa, H.; Ishibashi, T.; Sato, H.; Takashima, K.; Tanifuji, S. (1993). "Report of the 1990/91 southern minke whale research cruise under scientific permit in Area V". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 43: 505–522.

- Risch, D.; Gales, N. J.; Gedamke, J.; Kindermann, L.; Nowacek, D. P.; Read, A. J.; Siebert, U.; Van Opzeeland, I. C.; Van Parijs, S. M.; Friedlaender, A. S. (2014). "Mysterious bio-duck sound attributed to the Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis)". Biology Letters. 10 (4): 1–8. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0175. PMC 4013705. PMID 24759372.

- Schevill, W. E.; Watkins, W. A. (1972). "Intense low-frequency sounds from an Antarctic minke whale, Balaenoptera acutorostrata". Breviora. 388: 1–8.

- Matthews, D., Macleod, R., and R. D. McCauley. (2004). "Bio-duck activity in the Perth Canyon: an automatic detection algorithm". In Proceedings of Acoustics 2004, 3–5 November 2004, Gold Coast, Australia, pp. 63–66.

- McCauley, R., Bannister, J., Burton, C., Jenner, C., Rennie, S., and C. S. Kent. (2004). "Western Australian exercise area blue whale project: final summary report". CMST Report R2004–29, Project 350, 1-73.

- Van Opzeeland, I.; Van Parijs, S.; Kindermann, L.; Boebel, O. (2010). ""Seasonal patterns in Antarctic blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus intermedia) vocalizations and the bio-duck signal". In Acoustic ecology of marine mammals in polar oceans". Rep. Polar Mar Res. 619: 251–278.

- Morelle, Rebecca (April 22, 2014). "Mystery of 'ocean quack sound' solved". BBC News. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- Bull, H. J. (1896). The cruise of the 'Antarctic' to the South Polar regions. London: Edward Arnold.

- Ainley, D. G. (2010). "A history of the exploitation of the Ross Sea, Antarctica". Polar Record. 46 (3): 233–243. doi:10.1017/s003224740999009x. S2CID 55624041.

- Ash, C. (1962). Whaler's Eye. George Allen and Unwin Ltd., London.

- Tønnessen, J. and A. O. Johnsen. (1982). The history of modern whaling. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Shimadzu, Y.; Kasamatsu, F. (1981). "Operating pattern of Japanese whaling expeditions engaged in minke whaling in the Antarctic". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 31: 349–355.

- Holt, S (1981). "History of the regulation of southern minke whaling: scientific advice and a response of industry". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 31: 319–322.

- Masaki, Y.; Yamamura, K. (1978). "Japanese whaling and whale sighting in the 1976/77 Antarctic season". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 28: 251–261.

- Furukawa, F (1981). "Minke whaling in the 34th Antarctic whaling season, 1979/80". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 31: 359–362.

- Ohsumi, S.; Masaki, Y. (1974). "Status of whale stocks in the Antarctic, 1972/73". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 24: 102–113.

- Masaki, Y.; Fukuda, Y. (1975). "Japanese pelagic whaling and sighting in the Antarctic, 1973/74". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 25: 106–128.

- Best, P (1974). "Status of whale stocks off Natal, 1972". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 24: 127–135.

- Da Rocha, J. M. (1983). "Revision of Brazilian whaling data". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 33: 419–427.

- Zahl, S (1990). "Analysis of Brazilian minke whale data from 1966-85". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 40: 325–328.

- Van Waerebeek, K.; Baker, A. N.; Félix, F.; Gedamke, J.; Iñiguez, M.; Sanino, G. P.; Secchi, E.; Sutaria, D.; van Helden, A.; Wang, Y. (2007). "Vessel collisions with small cetaceans worldwide and with large whales in the Southern Hemisphere, an initial assessment" (PDF). Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals. 6 (1): 43–69. doi:10.5597/lajam00109.

- "Appendix I and Appendix II Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009.

- "CMS Pacific Cetaceans MOU for Cetaceans and their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region".

External links

Media related to Balaenoptera bonaerensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Balaenoptera bonaerensis at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Balaenoptera bonaerensis at Wikispecies

Data related to Balaenoptera bonaerensis at Wikispecies