Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat (French: [ʒɑ̃ miʃɛl baskja]; December 22, 1960 – August 12, 1988) was an American artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent. Basquiat first achieved fame as part of SAMO, a graffiti duo who wrote enigmatic epigrams in the cultural hotbed of the Lower East Side of Manhattan during the late 1970s, where rap, punk, and street art coalesced into early hip-hop music culture. By the early 1980s, his neo-expressionist paintings were being exhibited in galleries and museums internationally. At 21, Basquiat became the youngest artist to ever take part in documenta in Kassel. At 22, he was the youngest to exhibit at the Whitney Biennial in New York. The Whitney Museum of American Art held a retrospective of his art in 1992.

Jean-Michel Basquiat | |

|---|---|

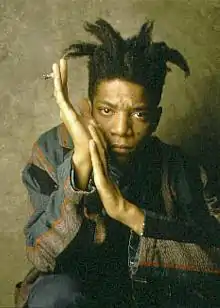

Basquiat by William Coupon in 1986 | |

| Born | December 22, 1960 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | August 12, 1988 (aged 27) New York City, U.S. |

| Style | |

| Movement | Neo-expressionism |

| Website | basquiat |

Basquiat's art focused on dichotomies such as wealth versus poverty, integration versus segregation, and inner versus outer experience. He appropriated poetry, drawing, and painting, and married text and image, abstraction, figuration, and historical information mixed with contemporary critique. Basquiat used social commentary in his paintings as a tool for introspection and for identifying with his experiences in the black community of his time, as well as attacks on power structures and systems of racism. Basquiat's visual poetics were acutely political and direct in their criticism of colonialism and support for class struggle.

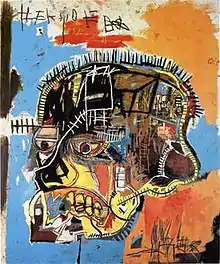

Since his death at the age of 27 from a heroin overdose in 1988, his work has steadily increased in value. At a Sotheby's auction in May 2017, Untitled, a 1982 painting by Basquiat depicting a black skull with red and yellow rivulets, sold for $110.5 million, becoming one of the most expensive paintings ever purchased. It also set a new record high for an American artist at auction.

Biography

Early life: 1960–1977

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York, on December 22, 1960, shortly after the death of his older brother, Max. He was the second of four children of Matilde Basquiat (née Andrades) (July 28, 1934 – November 17, 2008)[1] and Gérard Basquiat (1930 – July 7, 2013).[2][3] He had two younger sisters: Lisane, born in 1964, and Jeanine, born in 1967.[4][1] His father, Gérard Basquiat, was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and his mother, Matilde Basquiat, who was of Puerto Rican descent, was born in Brooklyn, New York.[5] Matilde instilled a love for art in her young son by taking him to art museums in Manhattan and enrolling him as a junior member of the Brooklyn Museum of Art.[3][6] Basquiat was a precocious child who learned how to read and write by the age of four and was a gifted artist. His teachers, including artist José Machado, noticed his artistic abilities, and his mother encouraged her son's artistic talent. In 1967, Basquiat started attending Saint Ann's School, an arts-oriented exclusive private school.[7][8][9] There he met his friend Marc Prozzo; together they created a children's book, written by Basquiat at the age of seven, and illustrated by Prozzo.[5][10]

At the age of seven in 1968, Basquiat was hit by a car while playing in the street. His arm was broken and he suffered several internal injuries; he eventually underwent a splenectomy.[11] While he was recuperating from his injuries, his mother brought him a copy of Gray's Anatomy to keep him occupied.[12] This book would prove to be influential in his future artistic outlook. His parents separated that year and he and his sisters were raised by their father.[12][3] His mother had been committed to a mental institution when he was 10 and thereafter spent her life in and out of institutions.[13] By the age of 11, Basquiat was fully fluent in French, Spanish and English, and an avid reader of all three languages.[14] His family resided in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, for five years, then moved to San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1974, where Basquiat studied at Saint John's School in Condado. After two years, they returned to New York City.[12]:39 Due to his mother's instability and family unrest, Basquiat ran away from home at 15.[3][12]:37 He slept on park benches in Washington Square Park, and was arrested then returned to the care of his father within a week.[15][16] Basquiat left Edward R. Murrow High School in the 10th grade and then attended City-As-School, an alternative high school in Manhattan, home to many artistic students who failed at conventional schooling.[17]

Street art: 1978–1980

—Franklin Sirmans, In the Cipher: Basquiat and Hip Hop Culture[18]

In May 1978, Basquiat and his schoolmate Al Diaz began spray painting graffiti on buildings in Lower Manhattan, working under the pseudonym SAMO (same old shit).[19][20] They inscribed poetic and satirical advertising slogans such as "SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO GOD."[19] In June 1978, Basquiat was expelled from City-As-School for pieing the principal.[21] At the age of 17, his father kicked him out of the house after he decided to drop out of school.[22] Basquiat worked for the Unique Clothing Warehouse at 718 Broadway in NoHo while continuing to write graffiti at night.[23][24] On December 11, 1978, The Village Voice published an article about the SAMO graffiti.[19]

In 1979, Basquiat appeared on the live public-access television show TV Party hosted by Glenn O'Brien, and the two started a friendship.[25] He made regular appearances on the show over the next few years.[25] In April 1979, Basquiat met Michael Holman at the Canal Zone Party and they formed the noise rock band Test Pattern, which was later renamed Gray.[26] Other members of Gray included Shannon Dawson, Nick Taylor, Wayne Clifford and Vincent Gallo. The band performed at nightclubs, such as Max's Kansas City, CBGB, Hurrah, and the Mudd Club.[26]

Around this time, Basquiat lived in the East Village with his friend Alexis Adler, a Barnard biology graduate.[27] He often copied diagrams of chemical compounds borrowed from Adler's science textbooks. She documented Basquiat's creative explorations as he transformed the floors, walls, doors and furniture into his artworks.[28] He also made postcards with his friend Jennifer Stein.[29] While selling postcards in SoHo, Basquiat spotted Andy Warhol at W.P.A. restaurant with art critic Henry Geldzahler.[12] He sold Warhol a postcard titled Stupid Games, Bad Ideas.[30]

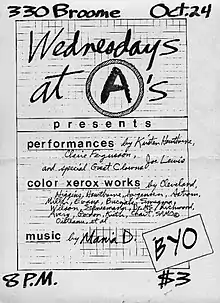

In October 1979, at Arleen Schloss's open space called A's, Basquiat showed his SAMO montages using color Xerox copies of his works.[31] Schloss also allowed Basquiat to use the space to create his "MAN MADE" clothing, which were upcycled garments he painted on.[32][33] In November 1979, costume designer Patricia Field carried his clothing line in her upscale boutique on 8th street in the East Village. Field also displayed his sculptures in the store window.[34]

After Basquiat and Diaz ended their friendship, the SAMO project ended with the epitaph "SAMO IS DEAD," inscribed on the walls of SoHo buildings in early 1980.[35] When they separated, a mock wave started for SAMO. Later that year, Basquiat began filming Glenn O'Brien's independent film Downtown 81 (2000), originally titled New York Beat. The film featured some of Gray's recordings on its soundtrack.[36]

Gallery artist: 1980–1985

During the early 1980s, Basquiat made his breakthrough as a solo artist. In June 1980, Basquiat participated in The Times Square Show, a multi-artist exhibition sponsored by Collaborative Projects Incorporated (Colab) and Fashion Moda.[37] He was noticed by various critics and curators, including Jeffrey Deitch, who wrote the first press mention of Basquiat in an article titled "Report from Times Square" in the September 1980 issue of Art in America.[38][39] In February 1981, Basquiat participated in the New York/New Wave exhibit, curated by Diego Cortez at New York's MoMA PS1.[40] Cortez organized Basquiat's first solo show with Emilio Mazzoli, an Italian gallerist, that opened in Modena, Italy on May 23, 1981.[41] In December 1981, Rene Ricard published "The Radiant Child" in Artforum magazine, the first extensive article on Basquiat.[42] During this period, Basquiat painted many pieces on objects he found in the streets, such as discarded doors.[43]

Basquiat sold his first painting, Cadillac Moon (1981), to singer Debbie Harry, frontwoman of the punk rock band Blondie, for $200.[44] They had filmed Downtown 81 together. Basquiat also appeared in the 1981 Blondie music video "Rapture," in a role originally intended for Grandmaster Flash, as a nightclub disc jockey.[45][46] At the time, Basquiat was living with his girlfriend, Suzanne Mallouk, who financially supported him as a waitress.[47] She later described his sexuality in Jennifer Clement's book, Widow Basquiat, as: "... not monochromatic. It did not rely on visual stimulation, such as a pretty girl. It was a very rich multichromatic sexuality. He was attracted to people for all different reasons. They could be boys, girls, thin, fat, pretty, ugly. It was, I think, driven by intelligence. He was attracted to intelligence more than anything and to pain."[48]

Art dealer Annina Nosei invited Basquiat to participate in her group show Public Address in 1981.[49] She provided him with materials and a space to work in the basement of her gallery.[21] In 1982, Nosei arranged for Basquiat to move into a loft which also served as a studio at 101 Crosby Street in SoHo.[50][51] Basquiat had his first American one-man show at the Annina Nosei Gallery in March 1982.[21] In March 1982, he painted in Modena for his second Italian exhibition.[52] By that summer, he had left the Annina Nosei Gallery and Bruno Bischofberger became his worldwide art dealer.[53] In June 1982, at 21 years old, Basquiat became the youngest artist to ever take part in documenta in Kassel, Germany, where his works were exhibited alongside Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, Gerhard Richter, Cy Twombly, and Andy Warhol.[54][22] Bischofberger gave Basquiat a one-man show in his Zurich gallery in September 1982.[55] He arranged for Basquiat to meet Warhol for lunch on October 4, 1982. Warhol recalled that Basquiat "went home and within two hours a painting was back, still wet, of him and me together."[56] The painting, Dos Cabezas (1982), ignited a friendship between them.[57] Basquiat was photographed by James Van Der Zee for an interview with Henry Geldzahler published in the January 1983 issue of Warhol's Interview magazine.[58]

In December 1982, Basquiat began working from the ground-floor display and studio space art dealer Larry Gagosian had built below his Venice, California home.[59] There, he commenced a series of paintings for a March 1983 show; his second at the Gagosian Gallery in West Hollywood.[60] Basquiat flew out his girlfriend, then-unknown singer Madonna, to accompany him.[61] Gagosian recalled:

Everything was going along fine. Jean-Michel was making paintings, I was selling them, and we were having a lot of fun. But then one day Jean-Michel said, "My girlfriend is coming to stay with me." I was a little concerned—one too many eggs can spoil an omelet, you know? So I said, "Well, what's she like?" And he said, "Her name is Madonna and she's going to be huge." I'll never forget that he said that. So Madonna came out and stayed for a few months and we all got along like one big, happy family.[62]

_home_on_57_Great_Jones_Street.jpg.webp)

Basquiat took considerable interest in the work that artist Robert Rauschenberg was producing at Gemini G.E.L. in West Hollywood, visiting him on several occasions and finding inspiration in his accomplishments.[60] While in Los Angeles, Basquiat painted Hollywood Africans (1983), which portrays himself with graffiti artists Toxic and Rammellzee.[63] Basquiat also produced a hip-hop record featuring Rammellzee and rapper K-Rob. Billed as Rammellzee vs. K-Rob, the single contained two versions of the same track: "Beat Bop" on the A-side with vocals, with the B-side adding an instrumental version.[64] It was pressed in limited quantities on the one-off Tartown Record Company label. Basquiat created the cover art for the single, making it highly desirable among both record and art collectors.[65]

In March 1983, at 22 years old, Basquiat was included in the Whitney Biennial, becoming the youngest artist to represent America in a major international exhibition of contemporary art.[66] That summer, Basquiat invited Lee Jaffe, a former musician in Bob Marley's band, to join him on a trip throughout Asia and Europe.[67][68] While in Tokyo, he was photographed for Issey Miyake.[69][70] Upon his return to New York, Basquiat was deeply affected by the death of Michael Stewart, an aspiring black artist in the downtown club scene who was killed by transit police in September 1983. He painted Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) (1983) in response to the incident.[71]

By 1984, Basquiat was showing at the Mary Boone Gallery in SoHo. Basquiat often painted in expensive Armani suits; and he would even appear in public in the same paint-splattered clothes.[72][73] On February 10, 1985, he appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in a feature titled "New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist".[15]

A large number of photographs depict a collaboration between Warhol and Basquiat in 1984 and 1985.[74] For their joint painting Olympics (1984), Warhol made the five-ring Olympic symbol rendered in the original primary colors and Basquiat painted over it in his animated style. They made another homage to the 1984 Summer Olympics with Olympic Rings (1985).[75] Other collaborative paintings include Taxi, 45th/Broadway (1984–85) and Zenith (1985). Their joint exhibition, Paintings, at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery caused a rift in their friendship after it was panned by critics and Basquiat was referred to as Warhol's mascot.[56]

Despite his artistic success, his emotional instability continued to haunt him and he used drugs frequently. His cocaine use became so excessive that he blew a hole in his nasal septum.[21] A friend claimed Basquiat confessed that he was on heroin in late 1980.[21] Many of his peers speculated that his heroin use was a means of coping with the demands of his newfound fame, the exploitative nature of the art industry, and the pressures of being a black man in the white-dominated art world.[76]

Final years and death: 1986–1988

In February 1986, Basquiat traveled to Atlanta, Georgia for an exhibit of his drawings at Fay Gold Gallery.[77] In August 1986, he flew to Ivory Coast for an exhibit organized by art dealer Bruno Bischofberger at the French Cultural Institute in Abidjan.[78] He was accompanied by his girlfriend Jennifer Goode.[79] She worked at Area nightclub, a frequent hangout spot for Basquiat. Goode unsuccessfully tried to get Basquiat into a methadone program.[80] In November 1986, at 25 years old, Basquiat became the youngest artist given an exhibit at Kestner-Gesellschaft in Hannover.[81]

Basquiat walked the runway for Rei Kawakubo at the Comme des Garçons Spring/Summer 1987 show in Paris.[82][83] In the last 18 months of his life, Basquiat became something of a recluse.[76] His continued drug use is thought to have been a way of coping after the death of Andy Warhol in February 1987.[84]

In January 1988, Basquiat traveled to Paris for his exhibit at the Yvon Lambert Gallery, and to Dusseldorf for an exhibit that same month at the Hans Mayer Gallery. In Paris, he befriended Ivorian artist Ouattara Watts. They made plans to travel together to Watts' birthplace, Korhogo, that summer.[85] Following an exhibition at Vrej Baghoomian's gallery in April 1988, Basquiat traveled to Maui in June 1988. When he returned, Keith Haring reported meeting with Basquiat, who was glad to tell him that he had finally kicked his drug dependency.[86]

Despite attempts at sobriety, Basquiat died of a heroin overdose at his studio on Great Jones Street in Manhattan's NoHo neighborhood on August 12, 1988.[21] He had been found unresponsive in his bedroom by his girlfriend Kelly Inman.[12][87] He was taken to Cabrini Medical Center, where he was pronounced dead on arrival.[12] He was 27 years old.[29]

A private funeral was held at Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel on August 17, 1988.[88] The funeral was attended by immediate family and close friends, including artists Keith Haring and Francesco Clemente.[88] Jeffrey Deitch, who wrote the first press mention of Basquiat and became his friend, gave a eulogy.[38] Basquiat is buried at Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery.[88]

A public memorial was held at Saint Peter's Church on November 3, 1988.[89] Among the speakers was Ingrid Sischy, who, as the editor of Artforum, got to know Basquiat well and commissioned a number of articles that introduced his work to the wider world.[90] His former girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk recited sections of A. R. Penck's "Poem for Basquiat" and his friend Fab 5 Freddy read a poem by Langston Hughes.[91] The 300 guests included musicians John Lurie and Arto Lindsay, Keith Haring, poet David Shapiro, writer Glenn O'Brien, and members of Basquiat's former band Gray.[89]

In memory of the late artist, Keith Haring created the painting A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat.[92] In the obituary he wrote for Vogue, Haring stated: "He truly created a lifetime of works in ten years. Greedily, we wonder what else he might have created, what masterpieces we have been cheated out of by his death, but the fact is that he has created enough work to intrigue generations to come. Only now will people begin to understand the magnitude of his contribution".[93][94]

Artistry

—Kellie Jones, Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (Re)Mix[95]

According to Franklin Sirmans, Basquiat appropriated poetry, drawing, and painting, and married text and image, abstraction, figuration, and historical information mixed with contemporary critique.[18] Fred Hoffman hypothesizes that underlying Basquiat's self-identification as an artist was his "innate capacity to function as something like an oracle, distilling his perceptions of the outside world down to their essence and, in turn, projecting them outward through his creative acts."[96] Additionally, continuing his activities as a graffiti artist, Basquiat often incorporated words into his paintings. Before his career as a painter began, he produced punk-inspired postcards for sale on the street, and became known for the political–poetical graffiti under the name of SAMO.[30] He would often draw on random objects and surfaces, including other people's clothing.[27] The conjunction of various media is an integral element of Basquiat's art. His paintings are typically covered with text and codes of all kinds: words, letters, numerals, pictograms, logos, map symbols, diagrams and more.[97]

Basquiat's art focused on recurrent "suggestive dichotomies", such as wealth versus poverty, integration versus segregation, and inner versus outer experience.[96] A middle period from late 1982 to 1985 featured multi-panel paintings and individual canvases with exposed stretcher bars, the surface dense with writing, collage and imagery. The years 1984–85 were also the main period of the Basquiat–Warhol collaborations, even if, in general, they were not very well received by the critics.[98] A major reference source used by Basquiat throughout his career was the book Gray's Anatomy, which his mother had given him while he was in the hospital aged seven.[11] It remained influential in his depictions of the human anatomy, and in its mixture of image and text as seen in Flesh and Spirit (1982–83). Other major sources were Henry Dreyfuss' Symbol Sourcebook, Leonardo da Vinci published by Reynal & Company, and Burchard Brentjes' African Rock Art.[99]

Heroes and saints

A prominent theme in Basquiat's work is the portrayal of historically prominent black figures, who were identified by Basquiat as black heroes and saints. His early works often featured the iconographic depiction of crowns and halos to distinguish heroes and saints in his specially chosen pantheon. "Jean-Michel's crown has three peaks, for his three royal lineages: the poet, the musician, the great boxing champion. Jean measured his skill against all he deemed strong, without prejudice as to their taste or age," said his friend and artist Francesco Clemente.[100] Reviewing Basquiat's show at the Bilbao Guggenheim, Art Daily noted that "Basquiat's crown is a changeable symbol: at times a halo and at others a crown of thorns, emphasizing the martyrdom that often goes hand in hand with sainthood. For Basquiat, these heroes and saints are warriors, occasionally rendered triumphant with arms raised in victory."[101] Basquiat was particularly a fan of bebop and cited saxophonist Charlie Parker as a hero.[15] He frequently referenced Parker and other jazz musicians in paintings such as Charles the First (1982) and Horn Players (1983), and King Zulu (1986).[44]

Drawings

_1982.jpeg.webp)

In his short career, Basquiat produced around 1500 drawings, as well as around 600 paintings and many sculpture and mixed media works.[102] Basquiat drew constantly, and often used objects around him as surfaces when paper was not immediately at hand.[103][104] Since childhood, Basquiat produced cartoon-inspired drawings when encouraged by his mother's interest in art, and drawing became a part of his expression as an artist.[105] Basquiat's drawings were produced in many different media, most commonly ink, pencil, felt-tip or marker, and oil-stick.[106] Basquiat sometimes used Xerox copies of fragments of his drawings to paste on to the canvas of larger paintings.[107]

The first public showing of Basquiat's paintings and drawings was in 1981 at the MoMA PS1 New York/New Wave exhibit. The article in Artforum magazine entitled "Radiant Child" was written by Rene Ricard after seeing the show brought Basquiat to the attention of the art world.[108] In 1984, Basquiat immortalized Ricard in two drawings, Untitled (Axe/Rene) and Rene Ricard,[109] representing the tension that existed between them.

A poet as well as an artist, words featured heavily in his drawings and paintings, with direct references to racism, slavery, the people and street scene of 1980s New York including other artists, and black historical figures, musicians and sports stars, as his notebooks and many important drawings demonstrate.[110][111] Often Basquiat's drawings were untitled, and as such to differentiate works a word written within the drawing is commonly in parentheses after Untitled, such as with Untitled (Axe/Rene). After Basquiat died, his estate was controlled by his father Gérard Basquiat, who also oversaw the committee which authenticated artworks, and operated from 1993 to 2012 to review over 1000 works, the majority of which were drawings.[112]

Heads

Heads and skulls are seen as significant focal points of many of Basquiat's most seminal works.[113] Heads in works like Untitled (Two Heads on Gold) (1982) and Philistines (1982) are reminiscent of African masks, which suggests a cultural reclamation.[113] The skulls allude to Haitian Vodou, which is filled with skull symbolism. The paintings Red Skull (1982) and Untitled (1982) can be seen as primary examples.[114] In reference to the potent image depicted in Untitled (Head) (1981), Fred Hoffman writes that Basquiat was likely, "caught off guard, possibly even frightened, by the power and energy emanating from this unexpected image."[96] Further investigation by Hoffman in his book The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat reveals a deeper interest in the artist's fascination with heads that proves an evolution in the artist's oeuvre from one of raw power to one of more refined cognizance.[115]

Heritage

—Lydia Lee[18]

Basquiat's diverse cultural heritage was one of his many sources of inspiration. He often incorporated Spanish words into his artworks like Untitled (Pollo Frito) (1982) and Sabado por la Noche (1984). Basquiat's La Hara (1981), a menacing portrait of a white police officer, combines the Nuyorican slang term for police (la jara) and the Irish surname O'Hara.[116] The black-hatted figure that appears in his paintings The Guilt of Gold Teeth (1982) and Despues De Un Pun (1987) is believed to represent Baron Samedi, the chief of the Guédé family of spirits in Haitian Vodou.[117]

Basquiat has various works deriving from African-American history, namely Slave Auction (1982), Undiscovered Genius of the Mississippi Delta (1983), Untitled (History of the Black People) (1983), and Jim Crow (1986).[118] Another painting, Irony of Negro Policeman (1981), is intended to illustrate how he believes African-Americans have been controlled by a predominantly Caucasian society. Basquiat sought to portray that African-Americans have become complicit with the "institutionalized forms of whiteness and corrupt white regimes of power" years after the Jim Crow era had ended.[119] This concept has been reiterated in additional Basquiat works, including Created Equal (1984). However, Kellie Jones, in her essay "Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (Re)Mix," posits that Basquiat's "mischievous, complex, and neologistic side, with regard to the fashioning of modernity and the influence and effluence of black culture" are often elided by critics and viewers, and thus "lost in translation."[95] Art historian Olivier Berggruen situates in Basquiat's anatomical screen prints, titled Anatomy, an assertion of vulnerability, one which "creates an aesthetic of the body as damaged, scarred, fragmented, incomplete, or torn apart, once the organic whole has disappeared. Paradoxically, it is the very act of creating these representations that conjures a positive corporeal valence between the artist and his sense of self or identity."[120]

Reception, exhibitions, and art market

Reception

Traditionally, the interpretation of Basquiat's works at the visual level comes from the subdued emotional tone of what they represent compared to what is actually depicted. For example, the figures in his paintings, as stated by Stephen Metcalf, "are shown frontally, with little or no depth of field, and nerves and organs are exposed, as in an anatomy textbook. Are these creatures dead and being clinically dissected, one wonders, or alive and in immense pain?"[51] In a similar vein, Jordana Moore Saggese states the action represented in the paintings of Basquiat have been referred to as a tribute to jazz indicating that, "Parker, Gillespie, and the other musicians of the bebop era infamously appropriated both the harmonic structures of jazz standards, using them as a structure for their own songs, and repeated similar note patterns across several improvisations."[121]

A second recurrent reference to Basquiat's aesthetics comes from the artist intention to share, in the words of Niru Ratnum, a "highly individualistic, expressive view of the world".[122] David Bowie, a collector of Basquiat's works, stated that "He seemed to digest the frenetic flow of passing image and experience, put them through some kind of internal reorganization and dress the canvas with this resultant network of chance."[123] Basquiat seems to invite us to, in the words of Luis Alberto Mejia Clavijo, "paint like a child, don't paint what is on the surface... Finally every energy you drop is marking a territory, is a traffic sign, is directing and feeding spirits. What seems like a mess for some of us in the Cartesian logic, it is maybe a clear spiritual route for some others."[124] Fred Hoffman stated that a painting from Basquiat typically "shows the artist's vitality and energy being continually challenged by life-draining organisms."[125] Reviews about his work have been written on the direct relation of painting and graffiti. Regarding the relation between painting and graffiti, Olivia Laing states: "Words jumped out at him, from the back of cereal boxes or subway ads, and he stayed alert to their subversive properties, their double and hidden meaning."[126]

In the words of the Marc Mayer essay "Basquiat in History", "Basquiat speaks articulately while dodging the full impact of clarity like a matador. We can read his pictures without strenuous effort—the words, the images, the colors and the construction—but we cannot quite fathom the point they belabor. Keeping us in this state of half-knowing, of mystery-within-familiarity, had been the core technique of his brand of communication since his adolescent days as the graffiti poet SAMO. To enjoy them, we are not meant to analyze the pictures too carefully. Quantifying the encyclopedic breadth of his research certainly results in an interesting inventory, but the sum cannot adequately explain his pictures, which requires an effort outside the purview of iconography ... he painted a calculated incoherence, calibrating the mystery of what such apparently meaning-laden pictures might ultimately mean."[127]

Exhibitions

Basquiat's first public exhibition in June 1980 was in the group effort The Times Square Show (with David Hammons, Jenny Holzer, Lee Quiñones, Kenny Scharf and Kiki Smith among others), held in a vacant building at 41st Street and Seventh Avenue in New York. In 1981, he had his first solo exhibition at Galleria d'Arte Emilio Mazzoli in Modena.[41] In late 1981, Basquiat joined the Annina Nosei Gallery in New York, where he had his first solo US exhibition from March 6 to April 1, 1982.[128] By then, he was showing regularly alongside other Neo-expressionist artists including Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Francesco Clemente and Enzo Cucchi. In 1982, he also had exhibits at the Gagosian Gallery in West Hollywood, Galerie Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich, and the Fun Gallery in New York.[129]

Major exhibitions of Basquiat's work have included Jean-Michel Basquiat: Paintings 1981–1984 at the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh in 1984, which traveled to the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam in 1985. In 1985, University Art Museum, Berkeley hosted Basquiat's first US solo museum exhibit.[130] His artwork was showcased at Kestner-Gesellschaft, Hannover in 1987 and 1989. The first retrospective to be held of his work was the Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York from October 1992 to February 1993; sponsored by AT&T, MTV, and Madonna.[131] It subsequently traveled to the Menil Collection in Texas; the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa; and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Alabama, from 1993 to 1994.[132] The catalog for this exhibition was edited by Richard Marshall and included several essays of different perspectives.[133]

The exhibition Basquiat was mounted by the Brooklyn Museum, New York, in 2005, and traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.[134][135] From October 2006 to January 2007, the first Basquiat exhibition in Puerto Rico took place at the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico (MAPR); produced by ArtPremium, Corinne Timsit and Eric Bonici.[136] Basquiat remains an important source of inspiration for a younger generation of contemporary artists all over the world such as Rita Ackermann and Kader Attia, as shown, for example, at the exhibition Street and Studio: From Basquiat to Séripop co-curated by Cathérine Hug and Thomas Mießgang and previously exhibited at Kunsthalle Wien, Austria, in 2010.[137]

Basquiat and the Bayou, a 2014 show presented by the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, focused on the artist's works with themes of the American South.[138] The Brooklyn Museum exhibited Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks in 2015.[139] In 2017, Basquiat Before Basquiat: East 12th Street, 1979–1980 exhibited as Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, which displayed works made by Basquiat during the year he lived with his friend Alexis Adler.[28] Later that year, the Barbican Centre in London exhibited Basquiat: Boom for Real.[140] In 2019, the Brant Foundation in New York, hosted an extensive exhibit of Basquiat's works with free admission.[141] All 50,000 tickets were claimed for before the exhibition opened, so additional tickets were released.[142] In June 2019, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York presented Basquiat's "Defacement": The Untold Story.[143] Later that year, the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne opened the exhibit Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines.[144] The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston will exhibit Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation from October 2020 to May 2021.[145] The Lotte Museum of Art will host the first major exhibition of Jean-Michel Basquiat in Seoul from October 2020 to February 2021.[146]

Criticism

In a review for The Telegraph, critic Hilton Kramer begins his first paragraph by stating that Basquiat had no idea what the word "quality" meant. The criticisms which follow relentlessly label Basquiat as a "talentless hustler" and a "street-smart but otherwise invincibly ignorant" arguing that art dealers of the time were "as ignorant about art as Basquiat himself." In saying that Basquiat's work never rose above "that lowly artistic station" of graffiti "even when his paintings were fetching enormous prices," Kramer argued that graffiti art "acquired a cult status in certain New York art circles." Kramer further opined that "As a result of the campaign waged by these art-world entrepreneurs on Basquiat's behalf—and their own, of course—there was never any doubt that the museums, the collectors and the media would fall into line" when talking about the marketing of Basquiat's name.[147]

According to Sirmans, Basquiat's visual poetics were acutely political and direct in their criticism of colonialism and support for class struggle.[18] As reviewed by Hoffman, Basquiat used social commentary in his paintings as a "springboard to deeper truths about the individual".[96] Art critic Bonnie Rosenberg compared Basquiat's work to the emergence of American Hip Hop during the same era. She also mentioned how Basquiat experienced a good taste of fame in his last years when he was a "critically embraced and popularly celebrated artistic phenomenon." Rosenberg remarked that some people focused on the "superficial exoticism of his work" missing the fact that it "held important connections to expressive precursors."[148] Shortly after his death, The New York Times indicated that Basquiat was "the most famous of only a small number of young black artists who have achieved national recognition."[76]

Art market

Notable private collectors of Basquiat's work have included David Bowie, Mera and Donald Rubell,[149] Peter Brant,[150] Lars Ulrich,[151] Steven A. Cohen,[149] Laurence Graff,[149] John McEnroe,[149] Madonna,[149] Debbie Harry, Leonardo DiCaprio,[152] Swizz Beatz,[153] Jay-Z,[154] and Johnny Depp.[155] Basquiat sold his first painting in 1981, and by 1982, spurred by the Neo-Expressionist art boom, his work was in great demand. Basquiat was on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in 1985, which was unprecedented for any young African-American artist.[156] Since Basquiat's death in 1988, the market for his work has developed steadily—in line with overall art market trends—with a dramatic peak in 2007 when, at the height of the art market boom, the global auction volume for his work was over $115 million. Brett Gorvy, deputy chairman of Christie's, is quoted describing Basquiat's market as "two-tiered. ... The most coveted material is rare, generally dating from the best period, 1981–83."[157]

Until 2002, the highest amount paid for an original work of Basquiat's was $3.3 million for Self-Portrait (1982), sold at Christie's in 1998.[158] In 2002, Basquiat's Profit I (1982) was sold at Christie's by drummer Lars Ulrich of the heavy metal band Metallica for $5.5 million.[159] The proceedings of the auction are documented in the 2004 film Metallica: Some Kind of Monster.

In June 2002, New York con-artist Alfredo Martinez was charged by the Federal Bureau of Investigation with attempting to deceive two art dealers by selling them $185,000 worth of fake Basquiat drawings.[160] The charges against Martinez, which landed him in Manhattan's Metropolitan Correction Center for 21 months, involved a scheme to sell drawings he copied from authentic artworks, accompanied by forged certificates of authenticity.[161] Martinez claimed he got away with selling fake Basquiat drawings for 18 years; he also forged works by Keith Haring.[162][163]

In 2007, Basquiat's painting Hannibal (1982) was seized by federal authorities as part of an embezzlement scheme by convicted Brazilian money launderer and former banker Edemar Cid Ferreira.[164] Ferreira had purchased the painting with illegally acquired funds while he controlled Banco Santos in Brazil.[164] It was shipped to a Manhattan warehouse, via the Netherlands, with a false shipping invoice stating it was worth $100.[165] The painting was later sold at Sotheby's for $13.1 million.[166]

Between 2007 and 2012, the price of Basquiat's work continued to steadily increase up to $16.3 million dollars.[167][168][169] The sale of Untitled (1981) for $20.1 million in 2012 elevated his market to a new stratosphere.[170] Soon other works in his oeuvre outpaced that record. Another Untitled (1981), depicting a fisherman, sold for $26.4 million in November 2012.[171] In May 2013, Dustheads (1982) sold for $48.8 million at Christie's.[172] In May 2016, Untitled (1982), depicting a devil, sold at Christie's for $57.3 million to Japanese businessman Yusaku Maezawa.[173] In May 2017, Maezawa purchased Basquiat's Untitled (1982), a powerful depiction of a black skull with red and yellow rivulets, at auction for a record-setting $110.5 million.[174] It is the most ever paid for an American artwork,[175] and the sixth most expensive artwork sold at an auction, surpassing Andy Warhol's Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster), which sold for $105 million in 2013.[176][177] Maezawa's two record breaking purchases of Basquiat artworks total nearly $170 million.

In May 2018, Flexible (1984) sold for $45.3 million, Basquiat's first post-1983 painting to surpass the $20 million mark.[178] In June 2020, Untitled (Head) (1982), sold for $15.2 million, a record for a Sotheby's online sale and a record for a Basquiat work on paper.[179] In July 2020, Loïc Gouzer's Fair Warning app announced that an untitled drawing on paper sold for $10.8 million, which is a record high for an in-app purchase.[180] Earlier that year, American businessman Ken Griffin purchased Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump (1982) for upwards of $100 million from art collector Peter Brant.[181][182]

Authentication committee

The authentication committee of the estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat was formed by the gallery that was assigned to handle the artist's estate and was dissolved in 2012.[183] Between 1994 and 2012, it reviewed over 2,000 works of art; the cost of the committee's opinion was $100.[183] The committee was headed by Gérard Basquiat. Members and advisers varied depending on who was available at the time when a piece was being authenticated, but they have included the curators and gallerists Diego Cortez, Jeffrey Deitch, John Cheim, Richard Marshall, Fred Hoffman, and Annina Nosei.[184]

In 2008, the authentication committee was sued by collector Gerard De Geer, who claimed the committee breached its contract by refusing to offer an opinion on the authenticity of the painting Fuego Flores (1983);[185] after the lawsuit was dismissed, the committee ruled the work genuine.[186] In early 2012, the committee announced that it would dissolve in September of that year and no longer consider applications.[187]

Legacy

Basquiat's legacy has influenced literature, film, music, and fashion. In 2018, a public square in the 13th arrondissement of Paris was named Place Jean-Michel Basquiat in his memory.[188] For the 2020-21 NBA season, the Brooklyn Nets honored Basquiat with a basketball jersey inspired by his art.[189][190]

Fashion

In 2007, Basquiat was listed among GQ's 50 Most Stylish Men of the Past 50 Years.[191] Basquiat often painted in expensive Armani suits and he walked the runway for the Comme des Garçons Spring/Summer 1987 collection.[192] To commemorate Basquiat's runway appearance, Comme des Garçons featured his prints in the brand's Fall/Winter 2018 collection.[193] Valentino's Fall/Winter 2006 collection paid homage to Basquiat.[194] Sean John created a capsule collection for the 30th anniversary of Basquiat's death in 2018.[195] Apparel and accessories companies that have featured Basquiat's work include Uniqlo,[196] Urban Outfitters, Supreme,[197] Herschel Supply Co.,[198] Alice + Olivia,[199] Olympia Le-Tan,[200] DAEM,[201] and Coach New York.[202] Footwear companies such as Dr. Martens,[203] Reebok,[189] and Vivobarefoot have also collaborated with Basquiat's estate.[204]

Film

Basquiat starred in Downtown 81, a vérité movie written by Glenn O'Brien and shot by Edo Bertoglio in 1981, but not released until 2000.[205] In 1996, eight years after the artist's death, a biographical film titled Basquiat was released, directed by Julian Schnabel, with actor Jeffrey Wright starring as Basquiat. David Bowie played the part of Andy Warhol. Schnabel was interviewed during the film's script development as a personal acquaintance of Basquiat. Schnabel then purchased the rights to the project, believing that he could make a better film.[206]

In 2006, the Equality Forum featured Jean-Michel Basquiat during LGBT history month.[207] A 2009 documentary film, Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child, directed by Tamra Davis, was first screened as part of the 2010 Sundance Film Festival and was shown on the PBS series Independent Lens in 2011.[106] Tamra Davis discussed her friendship with Basquiat in a Sotheby's video, "Basquiat: Through the Eyes of a Friend".[208] In 2017, Sara Driver directed a documentary film, Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, which had its world premiere at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival.[35] In 2018, PBS broadcast a 90-minute documentary about Basquiat as part of the American Masters series, entitled Basquiat: Rage to Riches.[46]

Literature

In 1991, poet Kevin Young produced a book, To Repel Ghosts, a compendium of 117 poems relating to Basquiat's life, individual paintings, and social themes found in the artist's work. He published a "remix" of the book in 2005.[209] In 1993, a children's book was released titled Life Doesn't Frighten Me, which combines a poem written by Maya Angelou with art made by Basquiat.[210] In 2000, writer Jennifer Clement wrote the memoir Widow Basquiat: A Love Story, based on the narratives told to her by Basquiat's former girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk. The first American edition was released in 2014.[48] In 2005, poet M. K. Asante published the poem "SAMO", dedicated to Basquiat, in his book Beautiful. And Ugly Too. In 2016, the children's book Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, written and illustrated by Javaka Steptoe, was released in 2016.[211] The biography, told from the perspective of a young prodigy, won the Caldecott Medal in 2017.[212] In 2019, illustrator Paolo Parisi wrote the graphic novel Basquiat: A Graphic Novel, following Basquiat's journey from street-art legend SAMO to international art-scene darling, up until his death.[213]

Music

Shortly after Basquiat's death, guitarist Vernon Reid of New York City funk metal band Living Colour wrote a song called "Desperate People", released on their album Vivid. The song primarily addresses the drug scene of New York at that time. Vernon states that Basquiat's death inspired him to write the song after receiving a phone call from Greg Tate informing Vernon of Basquiat's death.[214]

On August 12, 2014, Revelation 13:18 released the single "Old School" featuring Jean-Michel Basquiat, along with the self-titled album Revelation 13:18 x Basquiat. The release date of "Old School" coincided with the anniversary of Basquiat's death. The single received attention after American rapper and producer Jay-Z dressed up as Basquiat for Halloween the same year as the release giving Revelation a nod.[215][216]

In April 2020, New York rock band the Strokes released their sixth studio album, The New Abnormal. The cover art featured Basquiat’s 1981 painting Bird on Money.

References

- "In Loving Memory: Matilde Basquiat" Archived July 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Lodge Communications 185, Harry S Truman Lodge No.1066, F.&A.M., December 4, 2008. New York, New York. Sad Tidings for Brother John Andrades.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat's Dad Leaves Behind Son's Art, and Tax Problem" Archived May 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine by James Fanelli, September 5, 2013, 6:27am.

- Hyped to Death by The New York Times (August 9, 1998).

- Braziel, Jana Evans (2008). Artists, Performers, and Black Masculinity in the Haitian Diaspora. Indiana University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-253-35139-5.

- jegede, dele (2009). Encyclopedia of African American Artists. ABC-CLIO. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-313-08060-9.

- Kwame, Anthony Appiah; Gates, Henry Louis (2005). Africana: Arts and Letters : An A-to-Z Reference of Writers, Musicians, and Artists of the African American Experience. Running Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-7624-2042-1.

- Phoebe Hoban, "One Artist Imitating Another," The New York Times

- Arthur C. Danto, "Flyboy in the Buttermilk," "The Nation"

- Lisa J. Curtis, "Homecoming: Fort Greene's poet-painter Basquiat is fondly remembered," "Brooklyn Paper"

- Basquiat, Jean-Michel; Berggruen, Olivier (2008). Basquiat. Fantasmi da scacciare. Ediz. bilingue (in Italian). Skira. p. 142. ISBN 978-88-6130-946-3.

- Emmerling, Leonard (2003). Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1960–1988. Taschen. p. 11. ISBN 3-822-81637-X.

- Hoban, Phoebe (September 26, 1988). "SAMO Is Dead: The Fall of Jean Michel Basquiat". New York. 21 (38). pp. 36–44. ISSN 0028-7369.

- Fretz 2010, p. 7

- Wilson, Jamia (February 1, 2018). Young Gifted and Black: Meet 52 Black Heroes from Past and Present. Wide Eyed Editions. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-78603-158-7.

- McGuigan, Cathleen (February 10, 1985). "NEW ART, NEW MONEY". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Manatakis, Lexi (November 21, 2017). "Jean-Michel Basquiat in his own words". Dazed. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- Gotthardt, Alexxa (December 1, 2017). "Basquiat Left School at 17—and Made New York Museums His Classroom". Artsy. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Sirmans, Franklin. (2005) In the Cipher: Basquiat and Hip Hop Culture from the book Basquiat. Mayer, Marc (ed.). Merrell Publishers in association with the Brooklyn Museum, ISBN 1-85894-287-X, pp. 91–105.

- Faflick, Philip (March 20, 2019). "Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Birth of SAMO". The Village Voice. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- Goldstein, Caroline (June 1, 2017). "Basquiat, the Teenage Years? A Trove of Unpublished Photos and Prints Is Released". artnet News. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Haden-Guest, Anthony (November 1988). "Burning Out". Vanity Fair. Vanity Fair. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- "21 Facts About Jean-Michel Basquiat". Sotheby's. June 21, 2019.

- Lim, Robert (October 15, 2015). "From Unique to Uniqlo: The Malling of Soho NYC". Heddels. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Beyer, Gregory (September 30, 2007). "$12,000 Postcards by Some Guy Named Basquiat". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Harris, Kelly (April 24, 2018). "The Enduring Style of an Underground '80s TV Show". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat's prolific artwork extended well past the canvas as noise-rock band Gray". AFROPUNK. October 7, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Straaten, Laura van (February 13, 2017). "The Jean-Michel Basquiat You Haven't Seen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- "Basquiat Before Basquiat: East 12th Street, 1979–1980". Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Dowd, Vincent (September 25, 2017). "Jean-Michel Basquiat: The neglected genius". BBC News. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Brumfitt, Stuart (September 19, 2017). "New York Inspiration | Tales from Teen Basquiat's Best Friend". Amuse. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- de la Haba, Gregory. "December 2012: In Conversation with Arlene Schloss". Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Mugrabi, Colby (May 21, 2019). "Exploring Jean-Michel Basquiat's 1970's Clothing Collection, 'Man Made.'". Garage. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Fretz 2010, p. 40

- "Man Made by Basquiat". Minnie Muse. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- N'Duka, Amanda (September 8, 2017). "'Boom For Real' Clip: Sara Driver's Documentary On Famed Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat – Toronto". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- Andy Kellman. Downtown 81 Original Soundtrack. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Brown, Emma (August 30, 2012). "Times Square: The Underbelly of New York Culture". Interview Magazine. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- Tomkins, Calvin (November 5, 2007). "A Fool for Art". The New Yorker. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- Deitch, Jeffrey (September 1980). "Report from Times Square". Art in America: 61.

- Kane, Ashleigh (January 26, 2018). "The New York curator who helped launch Basquiat's career". Dazed. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- "Sotheby's Brings Basquiat Held in Italy for 35 Years to London". Art Market Monitor. June 8, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- "The Radiant Child". Artforum. December 1981. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat: Street As Studio". Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- Eshun, Ekow (September 22, 2017). "Bowie, Bach and Bebop: How Music Powered Basquiat". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat: Artist Biography-Early Training". The Art Story Foundation. 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- American Masters — Basquiat: Rage to Riches (Season 32, Episode 7). Public Broadcasting Service. Broadcast: 2018-09-14.

- Sawyer, Miranda (September 3, 2017). "The Jean-Michel Basquiat I knew…". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- Clement, Jennifer (2014). Widow Basquiat: A Love Story. Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0553419917.

- "'IT'S CULTURE OR IT'S NOT CULTURE': An Interview with Annina Nosei". Artsy. March 4, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- Maitland, Hayley (September 20, 2017). "American Graffiti: Memories of Jean-Michel Basquiat". British Vogue. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Metcalf, Stephen (July–August 2018). "The Enigma of the Man Behind the $110 Million Painting". The Atlantic.

- Emmerling, Leonhard (2003). Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1960-1988. Taschen. p. 31. ISBN 978-3-8228-1637-0.

- "History". Galerie Bruno Bischofberger. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- "documenta 7 - Retrospective - documenta". www.documenta.de. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- Hoban, Phoebe (May 17, 2016). Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-5040-3450-0.

- "The best, worst, and weirdest parts of Warhol and Basquiat's friendship". Dazed. May 28, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "Warhol and Basquiat". Phillips. July 13, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Geldzahler, Henry (March 25, 2011). "From the Subways to Soho". Interview Magazine. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Fretz 2010, p. 109

- Fred Hoffman (March 13, 2005), Basquiat's L.A. – How an '80s interlude became a catalyst for an artist's evolution Los Angeles Times.

- Jones, Alice (January 10, 2013). "Larry Gagosian reminisces about the days Madonna was his driver". The Independent. London.

- Brant, Peter M. (November 27, 2012). "Larry Gagosian". Interview Magazine. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hollywood Africans, 1983". whitney.org. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- "Rammellzee vs. K-Rob 12" single produced by Jean-Michel Basquiat". Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- Nosnitsky, Andrew (November 14, 2013). "Basquiat's 'Beat Bop': An Oral History of One of the Most Valuable Hip-Hop Records of All Time". Spin. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat: 'Painter to the core'". Christie's. September 23, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "The Artist Who Travelled the World with Basquiat". Elephant. July 15, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Scheinfeld, Jillian (June 27, 2019). "The Intimate, Marijuana-Laced Portraiture of Lee Jaffe". Interview Magazine. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Manatakis, Lexi (November 27, 2018). "Unseen photos of Jean-Michel Basquiat wearing Issey Miyake in the 80s". Dazed. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Marain, Alexandre (December 10, 2018). "Never-before-seen photos of Basquiat from the 1980s are on display in Paris". Vogue Paris. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Schjeldahl, Peter (July 8, 2019). "Basquiat's Memorial to a Young Artist Killed by Police". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- Dazed (February 16, 2017). "The meaning and magic of Basquiat's clothes". Dazed. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Cork, Richard (2003). New Spirit, New Sculpture, New Money: Art in the 1980s. Yale University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-300-09509-0.

- Vanderhoof, Erin (July 31, 2019). "Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and the Friendship That Defined the Art World in 1980s New York City". Vanity Fair. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol: Olympic Rings, June 19 – August 11, 2012 Gagosian Gallery, London.

- Wines, Michael (August 27, 1988). "Jean Michel Basquiat: Hazards Of Sudden Success and Fame". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- Hoban 2004, p. 276

- Jacobs, Sean. "When Basquiat went to Africa". Africa Is a Country. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- Hoban 2004, p. 278

- "Jennifer Goode and Area's Heydey". Interview Magazine. February 13, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- "Jean Michel Basquiat - Artists - Leila Heller Gallery". www.leilahellergallery.com. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Bobb, Brooke (November 2, 2018). "If You've Got $20,000 to Spare, You Can Own Jean-Michel Basquiat's Favorite Comme des Garçons Coat". Vogue. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- Pace, Lilly; Kelly, Alyssa (August 2, 2019). "Comme des Garçons Muses Throughout History". CR Fashion Book. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- Newman, Robert (March 16, 2018). "Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Rise and Fall". Hamilton-Selway. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- Emmerling, Leonhard (2003). Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1960-1988. Taschen. p. 76. ISBN 978-3-8228-1637-0.

- Jean Michel Basquiat. Taschen Press (2018). Page 440.

- Michals, Susan (November 17, 2010). "Rare Polaroids and Snapshots of Jean-Michel Basquiat". Vanity Fair. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Basquiat, Jean-Michel (June 4, 2019). Basquiat-isms. Princeton University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-691-19283-3.

- "Basquiat Memorial". The New York Times. November 3, 1988. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- Sischy, Ingrid (May 2014). "For The Love of Basquiat". Vanity Fair. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Phoebe Hoban: Basquiat – A Quick Killing in Art The New York Times Books.

- Muir, Robin (May 7, 1999). "Keith Haring". The Independent. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Haring, Keith (September 29, 2020). Haring-isms. Princeton University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-691-20985-2.

- Lindy, Percival (November 22, 2019). "Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat: art stars who shone too briefly". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (Re)Mix, by Kellie Jones, from the book Basquiat, edited by Marc Mayer, 2005, Merrell Publishers in association with the Brooklyn Museum, ISBN 978-1-85894-287-2, pp. 163–179.

- Hoffman, Fred. (2005) The Defining Years: Notes on Five Key Works from the book Basquiat. Mayer, Marc (ed.). Merrell Publishers in association with the Brooklyn Museum, ISBN 1-85894-287-X, pp. 129–139.

- Berger, John (2011). "Seeing Through Lies: Jean-Michael Basquiat". Harper's. Harper's Foundation. 322 (1, 931): 45–50. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- Scott, Chadd. "Judge Jean-Michel Basquiat-Andy Warhol Collaborations For Yourself At Jack Shainman Gallery's The School". Forbes. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Basquiat and Books". Barbican. December 8, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat | Heroes and Saints". Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- "'Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now's the Time' on view at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao". Artdaily. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- Gregory, Alice (August 2015). "New Art". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Cumming, Laura (September 24, 2017). "Basquiat: Boom for Real review – restless energy". the Guardian. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Jean-Michel Basquiat". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- Steel, Rebecca. "The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat: Legacy of a Cultural Icon". Culture Trip. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- Davis, Tamra. "Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child" (One of the "Film Topics" sub-sections on the Independent Lens website and the documentary of the same name they describe). Independent Lens. PBS. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

Tamra Davis explains why she locked her footage of her friend Basquiat in a drawer for two decades, and what it took to be sure a film about him took the full measure of the man.

- Haden-Guest, Anthony. "Jean-Michel Basquiat". Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- Holzwarth, Hans W. (2009). 100 Contemporary Artists A-Z (Taschen's 25th anniversary special ed.). Köln: Taschen. pp. 54–61. ISBN 978-3-8365-1490-3.

- "Rene Ricard by Jean-MichelBasquiat". www.artnet.com. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- "Glenn O'Brien on the notebooks and drawings of Jean-Michel Basquiat". www.artforum.com. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- Magazine, Wallpaper* (April 7, 2015). "Inner workings: the notebooks of Jean-Michel Basquiat are unveiled at the Brooklyn Museum". Wallpaper*. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat's Dad Leaves Behind Son's Art, and Tax Problem". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- Lee, Shannon (July 9, 2020). "Why Basquiat's Heads Are His Most Sought-After Works". Artsy. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Is this Basquiat worth $110m? Yes – his art of American violence is priceless". the Guardian. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- Hoffman, Fred. The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Gallerie Enrico Navarra / 2017

- Ben-Meir, Sam (August 21, 2019). "Basquiat's Story We Need to Hear". The Wire. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Saggese, Jordana Moore (May 30, 2014). Reading Basquiat: Exploring Ambivalence in American Art. Univ of California Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-520-27624-6.

- "Iconic Artworks: Basquiat's Undiscovered Genius of the Mississippi Delta". Artland Magazine. July 1, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- Frohne, Andrea (1999). "Representing Jean-Michel Basquiat". In Okpewho, Isidore; Carole Boyce Davies; Ali Al'Amin Mazrui (eds.). The African Diaspora: African Origins and New World Identities (1st ed.). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 439–451. ISBN 978-0-253-33425-1.

- Berggruen, Olivier (2011). "Some Notes on Jean-Michel Basquiat's Silk-Screen Prints". The Writing of Art. Pushkin Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-906548-62-9.

- Jordana Moore Saggese (Jun 30, 2015), Basquiat, Horn Players Khan Academy.

- Niru Ratnam (Nov 16, 2013), Do you think this painting is worth $48.4 million? The Spectator.

- Ekow eshun (Sep 25, 2017), Bowie, Bach and Bebop: How music powered Basquiat Independent.

- Luis Alberto Mejia Clavijo (Jul 11, 2012), Voodoo Child: Ernok of Jean Michel Basquiat Contemporary Art Theory.

- Fred Hoffman (Dec 22, 2013), Notes on Five Key Jean-Michel Basquiat Works American Suburb X.

- Olivia Laing (Sep 8, 2017), Race, power, money – the art of Jean-Michel Basquiat The Guardian.

- Basquiat, edited by Marc Mayer, 2005, Merrell Publishers in association with the Brooklyn Museum, ISBN 978-1-85894-287-2, p. 50.

- Jean-Michel Basquiat MoMA Collection, New York.

- Gotthardt, Alexxa (April 1, 2018). "What Makes 1982 Basquiat's Most Valuable Year". Artsy. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Jean Michel Basquiat / MATRIX 80 | BAMPFA". bampfa.org. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- D'Arcy, David (November 1, 1992). "Whitney compares Basquiat to Leonardo da Vinci in new retrospective". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- Smith, Roberta (October 23, 1992). "Review/Art; Basquiat: Man For His Decade". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- Marshall, Richard. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Abrams / Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992 (out of print).

- "Basquiat". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- Mayer, Marc, Hoffman Fred, et al. Basquiat, Merrell Publishers / Brooklyn Museum, 2005.

- "Basquiat: An anthology for Puerto Rico". www.e-flux.com. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- "Street and Studio". Kunsthalle Wien. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- MacCash, Doug (November 11, 2014). "'Basquiat and the Bayou,' the No. 1 Prospect.3 art festival stop in New Orleans". NOLA.com. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- "Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- "Basquiat: Boom for Real exhibition, 21 Sep 2017—28 Jan 2018 | Barbican". www.barbican.org.uk. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- Cascone, Sarah (April 8, 2019). "The Basquiat Show at the Brant Foundation Is Such a Big Hit That Organizers Are Releasing More Free Tickets". artnet News. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- "Interview by Jeffrey Brown on Basquiat Brant Foundation exhibit. May 6, 2019". PBS News Hour. May 6, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- "Basquiat's "Defacement": The Untold Story". Guggenheim. October 15, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- "Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat | NGV". National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- "Writing the Future". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- Park, Yuna (July 20, 2020). "Lotte Museum of Art to host first major exhibition of Jean-Michel Basquiat in Seoul". The Korea Herald. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- "He had everything but talent". The Daily Telegraph. March 22, 1997. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works". The Art Story. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- Adam, Georgina; Harris, Gareth (June 17, 2010). "Basquiat comes of age". theartnewspaper.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013.

- Kazakina, Katya (March 6, 2019). "Basquiats Worth $1 Billion on Display at Brant Foundation Show". Bloomberg. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Eddy, Chuck (2011). Rock and Roll Always Forgets: A Quarter Century of Music Criticism. Duke University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-822-35010-1.

- Pasori, Cedar (April 22, 2013). "Leonardo DiCaprio Talks Saving the Environment with Art, Collecting Basquiat, and Being Named After da Vinci". complex.com. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- "Jay-Z Cops Basquiat Painting From Swizz Beatz". vibe.com. June 30, 2013. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- Sheehy, Kate (November 20, 2013). "Jay Z snaps up $4.5M Basquiat painting". nypost.com. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- France, Lisa Respers (June 10, 2016). "Johnny Depp auctioning off multimillion-dollar art collection". CNN.com. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- Jean-Michel Basquiat, February 7 – April 6, 2013 Gagosian Gallery, New York.

- Georgina Adam and Gareth Harris (June 17, 2010), Basquiat comes of age The Art Newspaper. Archived August 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Vogel, Carol (November 13, 1998). "Graffiti Artist Makes Good: A Basquiat Sells for a Record $3.3 Million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Horsley, Carter. "Art/Auctions: Post-War & Contemporary Art evening auction, May 14, 2002 at Christie's". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- Artdaily. "Basquiat Forger Arrested By FBI". artdaily.cc. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Lehmann, John (February 27, 2003). "Fraud Artist Finds Prison Less Filling". New York Post. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Spies, Michael (February 13, 2007). "Trigger Happy". The Village Voice. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Nelson, Joe Heaps. "July 2013: In Conversation with Alfredo Martinez". Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Cohen, Patricia (May 13, 2013). "Valuable as Art, but Priceless as a Tool to Launder Money". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- Kinsella, Eileen (June 19, 2015). "Bad Banker's $8 Million Basquiat Smuggled With Shipping Invoice for $100 Returns Home". artnet News. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- Freeman, Nate (October 7, 2016). "Sotheby's Contemporary Sale Nets $59.6 M., Beating High Estimate, With $13.1 M. Basquiat Leading the Way". ARTnews. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- "Huge bids smash modern art record". BBC. May 16, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Vogel, Carol (May 11, 2012). "Basquiat Painting Brings $16.3 Million at Phillips Sale". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Souren Melikian (June 29, 2012), Wary Buyers Still Pour Money Into Contemporary Art International Herald Tribune.

- Harris, Gareth (August 31, 2012). "Basquiat leaps into different league: A market analysis". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- "Records set for Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jeff Koons". CBC News. November 15, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- "Basquiat's Most Expensive Works at Auction". Artnet.com. May 16, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Robin Pogrebin, A Collector's-Eye View of the Auctions The New York Times May 15, 2016

- Pogrebin, Robin; Reyburn, Scott, eds. (May 18, 2017). "A Basquiat Sells for 'Mind-Blowing' $110.5 Million at Auction". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- D'Zurilla, Christie, ed. (May 18, 2017). "Basquiat painting sells for $110.5 million, the most ever paid for an American artwork". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- Press, ed. (May 24, 2017). "A Price on Genius". The Index. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- Mullen, Jethro, ed. (May 19, 2017). "Basquiat tops Warhol after painting sells for $111 million". CNN Money. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- Armstrong, Annie (May 18, 2018). "$45.3 M. Basquiat Is Top Lot in Robust $131.6 M. Phillips Sale of 20th-Century and Contemporary Art". ARTnews. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- Villa, Angelica (July 3, 2020). "Mitchell, Basquiat Top $41 M. Phillips Contemporary Evening Sale, Thirst for Young Artists Brings New Records". ARTnews. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- "Art Industry News: Loïc Gouzer's Fair Warning Sold a Basquiat for $10.8 Million, a Record for an In-App Purchase of Anything + Other Stories". artnet News. July 31, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- Johnson, Steve (July 25, 2020). "Now hanging at the Art Institute: Chicago billionaire Ken Griffin's new, $100 million Basquiat canvas". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- Kazakina, Katya (June 4, 2020). "Ken Griffin Buys Basquiat Painting for More Than $100 Million". Bloomberg. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- Daniel Grant (September 29, 1996), The tricky art of authentication Baltimore Sun.

- Liza Ghorbani (September 18, 2011), The Devil on the Door New York Magazine.

- Kate Taylor (May 1, 2008), Lawsuits Challenge Basquiat, Boetti Authentication Committees New York Sun.

- Georgina Adam and Riah Pryor (December 11, 2008), The law vs scholarship The Art Newspaper. Archived May 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Kinsella, Eileen (January 24, 2012). "Basquiat Committee to Cease Authenticating Works". ARTnews.com. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- Thiessen, Tamara (December 7, 2019). "American Street Art Pioneer, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Immortalized In Paris". Forbes. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- Stewert, Nan (October 29, 2020). "Anyone for Basquiatball? The Brooklyn Nets Will Adopt Jerseys Inspired by Jean-Michel Basquiat for Its Upcoming Season". artnet News. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Lewis, Brian (October 29, 2020). "Nets honor Basquiat, a Kevin Durant favorite, with new alternate threads". New York Post. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- gq.com (September 13, 2007). "The 50 Most Stylish Men of the Past 50 Years". GQ. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- Balster, Trisha (February 22, 2018). "Know your Icons: Tracing the Basquiat Fashion Influence". INDIE Magazine. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Tesema, Feleg (October 2, 2018). "These CdG SHIRT x Basquiat Pieces Are an Art Lover's Dream". Highsnobiety. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Phelps, Nicole (March 5, 2006). "Valentino Fall 2006 Ready-to-Wear Collection". Vogue. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- "This Sean John Capsule Collection Celebrates Basquiat on the 30th Anniversary of His Death". Remezcla. February 23, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Pauly, Alexandra (September 1, 2020). "UNIQLO UT to Launch Jean-Michel Basquiat x Warner Bros. Collection". HYPEBAE. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Li, Maverick (December 22, 2020). "Is Jean-Michael Basquiat the Original Father of Streetwear?". CR Fashion Book. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Tesema, Feleg (June 21, 2019). "These New Herschel Supply Bags Are Perfect for Basquiat Lovers". Highsnobiety. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Cheng, Andrea (November 4, 2016). "Alice + Olivia Launches a Jean-Michel Basquiat Fashion Collection". InStyle. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Mira, Nicola (October 15, 2018). "Olympia Le-Tan launches Jean-Michel Basquiat-inspired handbag line". Fashion Network. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Carmichael, Maiya (December 10, 2020). "The DAEM x Basquiat Collaboration Tells More Than Time". Essence. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- "Coach meets Jean-Michel Basquiat in this year's coolest collaboration". Vogue Australia. October 11, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Solomon, Tessa (July 10, 2020). "Dr. Martens Unveils New Collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat Estate". ARTnews.com. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Solomon, Tessa (October 8, 2020). "Vivobarefoot to Sell Shoes Hand-Painted with Basquiat's Most Iconic Designs". ARTnews.com. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Cassell, Dessane Lopez (November 6, 2019). "The Bittersweet Nostalgia of Watching Basquiat in Downtown 81". Hyperallergic. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Meet the Artist: Julan Schnabel", lecture given at Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC, May 13, 2011.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat". lgbthistorymonth.com.

- "Basquiat: Through the Eyes of a Friend". Sotheby's. May 2017.

- Kevin Young, To Repel Ghosts (1st edition), Zoland Books, 2001.

- "Maya Angelou and Basquiat made a book to help make life less frightening". Dazed. January 10, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- "Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat". Publishers Weekly.

- LSCHULTE (December 21, 2017). "2017 Caldecott Medal and Honor Books". Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- Paolo Parisi, Basquiat: A Graphic Novel (1st edition), Laurence King Publishing, 2019.

- GuitarManiaEU (March 30, 2013). "Living Colour – Interview with Vernon Reid". Retrieved December 29, 2016 – via YouTube.

- "Jay Z and Beyoncé Dressed Up as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Frida Kahlo for Halloween". Complex. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- "Jean-Michel Basquiat | Album Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

Further reading

- Buchhart, Dieter, Glenn O'Brien, Jean-Louis Prat, Susanne Reichling. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hatje Cantz, 2010. ISBN 978-3-7757-2593-4

- Buchhart, Dieter, and Eleanor Nairne. Basquiat: Boom for Real. (Catalogue for 2017 Exhibition at the Barbican Centre.) London: Prestel Publishing, 2017. ISBN 9783791356365

- Clement, Jennifer. Widow Basquiat: A Love Story, Broadway Books, 2014. ISBN 978-0553419917

- Deitch J., D. Cortez, and Glen O'Brien. Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1981: the Studio of the Street, Charta, 2007. ISBN 978-88-8158-625-7

- Fretz, Eric. Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Biography. Greenwood, 2010. ISBN 978-0-313-38056-3

- Hoban, Phoebe. Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art (2nd edn), Penguin Books, 2004. ISBN 9780143035121

- Hoffman, Fred. Jean-Michel Basquiat Drawing: Work from the Schorr Family Collection, Rizzoli/Acquavella Galleries, 2014. ISBN 978-0-8478-4447-0

- Hoffman, Fred. The Defining Years: Notes on Five Key Works, in Basquiat / Merrell Publishers / Brooklyn Museum, 2005, p. 13)

- Hoffman, Fred. The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Gallerie Enrico Navarra / 2017 ISBN 978-2911596537

- Marenzi, Luca. Jean-Michel Basquiat. Charta, 1999. ISBN 978-88-8158-239-6

- Marshall, Richard. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Abrams / Whitney Museum of American Art. Hardcover 1992, paperback 1995. (Catalog for 1992 Whitney retrospective, out of print).

- Marshall, Richard. Jean-Michel Basquiat: In World Only. Cheim & Read, 2005. (out of print).

- Mayer, Marc, Fred Hoffman, et al. Basquiat, Merrell Publishers / Brooklyn Museum, 2005.

- Tate, Greg. Flyboy in the Buttermilk. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. ISBN 978-0-671-72965-3

External links

| Library resources about Jean-Michel Basquiat |

| By Jean-Michel Basquiat |

|---|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jean-Michel Basquiat. |

Quotations related to Jean-Michel Basquiat at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Jean-Michel Basquiat at Wikiquote- Official website

- Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Fun Gallery, video excerpt from "Young Expressionists" (ART/New York #19), 1982.

- Jean-Michel Basquiat, BBC World Service program on Basquiat

- Jean-Michel Basquiat at IMDb

- Jean-Michel Basquiat on iTunes

- Jean-Michel Basquiat Tribute Site