Kafr Kanna

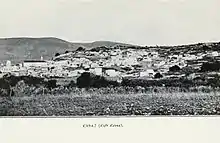

Kafr Kanna (Arabic: كفر كنا, Kafr Kanā; Hebrew: כַּפְר כַּנָּא) is an Arab town, in Galilee, part of the Northern District of Israel. It is associated with the New Testament village of Cana, where Jesus turned water into wine.[3][4] In 2019 its population was 22,751.[1]

Kafr Kanna

| |

|---|---|

Local council (from 1968) | |

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | Kpar Kannaˀ |

| • Also spelled | Kafar Kanna (official) Kufr Kana (unofficial) |

Kafr Kanna  Kafr Kanna | |

| Coordinates: 32°45′N 35°21′E | |

| Grid position | 182/239 PAL |

| Country | |

| District | Northern |

| Government | |

| • Head of Municipality | Yousef Awawdeh |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10,600 dunams (10.6 km2 or 4.1 sq mi) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 22,751 |

| • Density | 2,100/km2 (5,600/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | "Village of Cana"[2] |

History

Ancient and classic period

Archaeological excavations by the Israel Antiquities Authority uncovered remains dating from the Neolithic to the Mamluk periods. Evidence for a large Early Bronze Age settlement was excavated adjacent to the perennial Kanna spring, overlaying a site dating to the Early Chalcolithic Period. A fortification wall indicates that the settlement was fortified.[5]

Kana was mentioned in the Amarna letters, and was known in the times of the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus.

On the outskirts of the modern town is the tomb of the Jewish sage, rabbi Simeon ben Gamliel, the Nasi (prince) of the Sanhedrin (legislative body of Ancient Israel), who became president of the Sanhedrin in 50 CE. His tomb has remained a Jewish pilgrimage site over the centuries.[6][7]

Middle Ages

Nasir-i-Khusraw visited the village in 1047 CE and described the place in his diary:

To the southward [of Kafar Kannah] is a hill, on the top of which they have built a fine monastery. It has a strong gate, and the tomb of the prophet Yunis (Jonas) [...] is shown within. Near the gate of the monastery is a well, and the water thereof is sweet and good. [...] Acre is 4 leagues distant.[8]

Kafr Kanna was conquered by the Crusaders in 1099. During this period, Ali of Herat wrote that one could see the Maqam of Jonas, and also the grave of his son, at Kafr Kanna. This was repeated by Yaqut al-Hamawi, although he only wrote of the tomb as being that of Jonas' father.[8] The name Casale Robert was used by Franks, beside variations on the Arab name. In August 1254 Julian the lord of Sidon sold it to the Knights Hospitaller.[9][10]

Around 1300, Kafr Kanna was described as being a large village, in which lived the chiefs of various tribes. The head tribe is called Kais al-Hamra ("Kais the Red.") According to the chronicler, Al-Dimashqi, the district Buttauf, called "the Drowned Meadow", belonged to the village.[8] Al-Dimashqi further remarked that the waters of the surrounding hills drained into the area, flooding it; as soon as the land is dried up grain was sown.[11]

Ottoman Empire

Under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, the village flourished in the 16th century, as it lay on the western trade route between Egypt and Syria.[13] High taxes of different kinds were levied on the busy market. Among other things it traded in cloths, produced in Galilee for international consumption. Public baths and ovens were also taxed.[14] In 1533, Ottoman officials recorded the population as 147 households, and by 1596 (or rather 1548) it grew to 475 Muslim taxpayers (426 households and 49 bachelors) and 96 Jewish taxpayers (95 households and 1 bachelor),[15] making it the sixth most populous locality in Palestine at the time. The villagers paid a fixed tax-rate of 25% on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, olive trees, fruit trees, cotton, goats and beehives, in addition to occasional revenues and a market toll; a total of 56,303 Akçe.[16][17] At the time, Kafr Kanna was one of a few market villages in the Safad Sanjak and the second largest after the city of Safed.[18] It was also the only locality in the sanjak besides Safed to have a public bathhouse.[19]

A map from Napoleon's invasion of 1799 by Pierre Jacotin showed the place, named as Cana,[20] and

David Roberts' The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia illustrated the same in two separate lithographs. Edward Robinson's 1841 Biblical Researches in Palestine wrote that "The monks of the present day, and all recent travellers, find the Cana of the New Testament, where Jesus converted the water into wine, at Kefr Kenna", however he argued that Cana's location was in fact at the ruins known as Kana el Jalil (Cana of Galilee).[21] In the 1881 PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP), described it as a stone-built village, containing 200 Christians and 200 Muslims.[22] A population list from about 1887 showed that Kefr Kenna had about 830 inhabitants; "the greater part Christians."[23]

British Mandate

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Kufr Kenna had a total population of 1,175; 672 Muslims and 503 Christians,[24] of the Christians, 264 were Orthodox, 82 Catholics, 137 were Melkite and 20 were Anglican.[25] The population had increased at the 1931 census to 1,378; 896 Muslims and 482 Christians, in a total of 266 houses.[26]

In the 1945 statistics, the population was 1,930; 1,320 Muslims and 610 Christians,[27] while the total land area was 19,455 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[28] Of this, 1,552 were allocated for plantations and irrigable land, 11,642 for cereals,[29] while 56 dunams were classified as built-up areas.[30]

Israel

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Kfar Kanna was captured by units of Israel's 7th Brigade in the second half of Operation Dekel (July 15–18, 1948).[31] On July 22, 1948 the two priests, Giuseppe Leombruni (Catholic) and Prochoros (Greek Orthodox), and the Christian mayor surrendered Kanna peacefully to the advancing Haganah troops, ensuring that the population can remain in the village.[32][33] Kafr Kanna remained under martial law until 1966.

On 30 March 1976, a resident of Kafr Kanna, Muhammad Yusuf Taha, was one of six people killed by the Israeli army during Land Day demonstrations.[34]

In November 2014, there were clashes for some days because Israeli police killed one Israeli Arab, who attacked a police van with a knife. The police said that they had fired warning shots before shooting him but relatives said he was shot in "cold blood" and images from closed-circuit television (CCTV) showed a police officer shooting at the man while he was backing away.[35]

The mayor of the town is Mujahed Awadeh.[35]

Religious significance

The town is identified by Christians as the town of Cana, where Jesus performed a miracle at the Marriage at Cana (John 2:1–12). According to the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1914, the identification of Kafr Kanna with Cana dates back to at least the 8th century. However, the general view starting from the 12th-century placed Cana at Khirbet Kana, a site 8.5 kilometres (5.3 mi) to the northwest of Kafr Kanna. Later, the traditional identification with Kafr Kanna reemerged strongly in the mid-14th-century and until the present day.[9]

Cana is also mentioned as the home town of the Apostle Bartholomew, as "Nathanael of Cana" in John 21:2.

The main churches in Kafr Kanna are the Franciscan Wedding Church, the Greek Orthodox Church of St George and the Baptist Church. Near the two is the (usually closed) Roman Catholic Chapel of the Apostle Bartholomew (Nathanael).[36][37]

Demographics

Kafr Kanna achieved local council status in 1968. In 2006, there were 18,000 residents,[38] The population grew to 20,832 in the 2014 census.[1] As of 2014, Christians formed about 11% of the population.[39][40]

As is the case with many other mixed Muslim-Christian towns in the region, the Christians generally tend to live in the oldest part of town. In Kafr Kanna—and in Kafr Yasif and 'Abud, among others—there are two ancient nuclei in the town: the earlier one where Christians live, and another (also hundreds of years old) where Muslims live.[41]

Sport

Hapoel Kafr Kanna and F.C. Tzeirei Kafr Kanna plays in Liga Alef (the third tier). Beitar Kafr Kanna both play in Liga Bet (the fourth tier). Maccabi Kafr Kanna, which dissolved in 2014, have played at the second level in the past.

Archaeology

In 2001, remains of a 4th-century BCE pottery kiln that produced everted rim storage jars were found adjacent to the Kanna spring.[42]

Notable residents

- Wasil Taha, resident, Knesset member, Balad party.

- Abdulmalik Dehamshe, resident, former Knesset member, United Arab List.

See also

References

- "Population in the Localities 2019" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Palmer, 1881, p. 127

- Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, pp. 367, 391-394

- The near-miracle in Kafr Kana

- Excavations and Surveys in Israel

- "Tomb of Shimon ben Gamliel vandalized", Jerusalem Post, April 21, 2006 (accessed August 7, 2012).

- Rabbi Shimon Ben Gamliel's tomb set ablaze, arson suspected, YNet News, November 15, 2009 (accessed August 7, 2012).

- Le Strange, 1890, p. 469

- Pringle, 1993, p. 285

- Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 321, no. 1217

- Le Strange, 1890, p. 470

- Thomson, 1859, vol 2, p. 120

- David, 2010, p. 189

- Rhode, 1979, pp. 142, 153–154, 159

- Petersen, 2005, p. 131. Note that Petersen only count the households (hana), and not the bachelors

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 187

- Note that Rhode, 1979, p. 6 writes that the register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied from the Safad-district was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9

- Rhodes 1979, pp. 153–154.

- Rhodes 1979, p. 159.

- Karmon, 1960, p. 166

- Biblical Researches in Palestine, 1841, p.204-208

- Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 363

- Schumacher, 1888, p. 184

- Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Nazareth, p. 38

- Barron, 1923, Table XVI, p. 51

- Mills, 1932, p. 74

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 8

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 62

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 109

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 159

- Morris, 2004, p. 421

- Cana commemorates the courage of Father Leombruni, Custodia Terrae Sanctae website, 5th June 2011

- Padre Giuseppe Leombruni, un francescano coraggioso, Christian Media Center, 6 July 2011

- Pappe, 2011, p. 241

- "Arab Israeli anger simmers in Galilee after deadly shooting". Yahoo! News. 10 November 2014.

- http://www.custodia.org/default.asp?id=2734

- http://goisrael.com/tourism_eng/tourist%20information/discover%20israel/cities/Pages/kafr%20kana.aspx

- Population of localities numbering above 1,000 residents and other rural populations on 31/12/2006 Central Bureau of Statistics

- כפר כנא 2014

- "Arab Christians in Israel" (PDF). iataskforce.org. Inter-Agency Task Force on Israeli Arab Issues. June 2014. pp. 1–2.

- Ellenblum, 2003, p. 144

- early remains in Kfar Cana

Bibliography

- Alexandre, Yardenna (2008-12-30). "Kafr Kanna" (121). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Alexandre, Yardenna (2011-04-07). "Kafr Kanna" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Alexandre, Yardenna (2012-02-19). "Kafr Kanna" (124). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Alexandre, Yardenna (2013-02-28). "Kafr Kanna" (125). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Alexandre, Yardenna (2013-12-31). "Kafr Kanna" (125). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- David, Abraham (24 May 2010). To Come to the Land: Immigration and Settlement in 16th-Century Eretz-Israel. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5643-9.

- Ellenblum, Ronnie (2003). Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521521871.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (pp. 168 -182, 474 - 476)

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Mariti, Giovanni (1792). Travels Through Cyprus, Syria, and Palestine; with a General History of the Levant. 1. Dublin: P. Byrne. (p. 351 ff)

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pappe, I. (2011). The Forgotten Palestinians. A History of the Palestinians in Israel. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13441-4.

- Petersen, Andrew (2005). The Towns of Palestine Under Muslim Rule. British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 1841718211.

- Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A-K (excluding Acre and Jerusalem). I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 39036 2.

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521 46010 7.

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century (PhD). Columbia University.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Thomson, W.M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. 2 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

External links

- Welcome To Kafr Kanna

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 6: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- "Israel: A Social Report" (PDF).

.svg.png.webp)