Kew Gardens, Queens

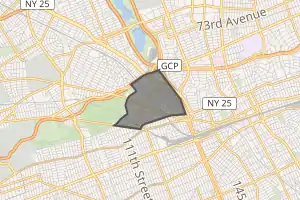

Kew Gardens is a neighborhood in the central area of the New York City borough of Queens. Kew Gardens, shaped roughly like a triangle, is bounded to the north by Union Turnpike and the Jackie Robinson Parkway (formerly the Interboro Parkway), to the east by the Van Wyck Expressway and 131st Street, to the south by Hillside Avenue, and to the west by Park Lane, Abingdon Road, and 118th Street. Forest Park and the neighborhood of Forest Hills are to the west, Flushing Meadows–Corona Park north, Richmond Hill south, Briarwood southeast, and Kew Gardens Hills east.

Kew Gardens | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Queens | |

Homestead Gourmet Shop and other stores on Lefferts Boulevard | |

Location within New York City | |

| Coordinates: 40.705°N 73.825°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | |

| County/Borough | |

| Community District | Queens 9[1] |

| Named for | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew[2] |

| Population | |

| • Total | 23,278 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| • White | 49.3% |

| • Hispanic | 24.3% |

| • Asian | 15.6% |

| • Black | 6.5% |

| • Other | 4.3% |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $61,287 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 11415 |

| Area codes | 718, 347, 929, and 917 |

| Website | www |

Kew Gardens is located in Queens Community District 9 and its ZIP Code is 11415.[1] It is patrolled by the New York City Police Department's 102nd Precinct.[5] Politically, Kew Gardens is represented by the New York City Council's 29th District.[6]

History

Early development

Kew Gardens was one of seven planned garden communities built in Queens from the late 19th century to 1950.[7] Much of the area was acquired in 1868 by Englishman Albon P. Man, who developed the neighborhood of Hollis Hill to the south, chiefly along Jamaica Avenue, while leaving the hilly land to the north undeveloped.[8]

Maple Grove Cemetery on Kew Gardens Road opened in 1875. A Long Island Rail Road station was built for mourners in October and trains stopped there from mid-November. The station was named Hopedale, after Hopedale Hall, a hotel located at what is now Queens Boulevard and Union Turnpike. In the 1890s, the executors of Man's estate laid out the Queens Bridge Golf Course on the hilly terrains south of the railroad. This remained in use until it was bisected in 1908 by the main line of the Long Island Rail Road, which had been moved 600 feet (180 m) to the south to eliminate a curve. The golf course was then abandoned and a new station was built in 1909 on Lefferts Boulevard. Man's heirs, Aldrick Man and Albon Man Jr., decided to lay out a new community and called it at first Kew and then Kew Gardens after the well-known botanical gardens in England.[2] The architects of the development favored English and neo-Tudor styles, which still predominate in many sections of the neighborhood.

Urbanization

In 1910, the property was sold piecemeal by the estate and during the next few years streets were extended, land graded and water and sewer pipes installed. The first apartment building was the Kew Bolmer at 80–45 Kew Gardens Road, erected in 1915; a clubhouse followed in 1916 and a private school, Kew-Forest School, in 1918. In 1920, the Kew Gardens Inn at the railroad station opened for residential guests, who paid $40 a week for a room and a bath with meals. Elegant one-family houses were built in the 1920s, as were apartment buildings such as Colonial Hall (1921) and Kew Hall (1922) that numbered more than twenty by 1936.

In July 1933, the Grand Central Parkway opened from the Kew Gardens Interchange to the edge of Nassau County.[9] Two years later, the Interboro (now Jackie Robinson) Parkway was opened, linking Kew Gardens to Pennsylvania Avenue in East New York.[10] Since the parkways used part of the roadbed of Union Turnpike, no houses were demolished.

Around the same time, the construction of the Queens Boulevard subway line offered the possibility of quick commutes to the central business district in Midtown Manhattan. In the late 1920s, speculators, upon learning the route of the proposed line, quickly bought up property on and around Queens Boulevard, and real estate prices soared, and older buildings were demolished in order to make way for new development.[11][12] In order to allow for the speculators to build fifteen-story apartment buildings, several blocks were rezoned.[13] They built apartment building in order to accommodate the influx of residents from Midtown Manhattan that would desire a quick and cheap commute to their jobs.[11][14] Since the new line had express tracks, communities built around express stations, such as in Forest Hills and Kew Gardens became more desirable to live. With the introduction of the subway into the community of Forest Hills, Queens Borough President George U. Harvey predicted that Queens Boulevard would become the "Park Avenue of Queens".[11] With the introduction of the subway, Forest Hills and Kew Gardens were transformed from quiet residential communities of one-family houses to active population centers.[15] The line was extended from Jackson Heights–Roosevelt Avenue to Kew Gardens–Union Turnpike on December 30, 1936.[16][17][18]

Following the line's completion, there was an increase in the property values of buildings around Queens Boulevard.[19] For example, a property along Queens Boulevard that would have sold for $1,200 in 1925, would have sold for $10,000 in 1930.[20] Queens Boulevard, prior to the construction of the subway, was just a route to allow people to get to Jamaica, running through farmlands. Since the construction of the line, the area of the thoroughfare that stretches from Rego Park to Kew Gardens has been home to apartment buildings, and a thriving business district that the Chamber of Commerce calls the "Golden Area".[21]

Later years

Despite its historical significance, Kew Gardens lacks any landmark protection.[7]

On November 22, 1950, two Long Island Rail Road trains collided in Kew Gardens. The trains collided between Kew Gardens and Jamaica stations, killing 78 people and injuring 363. The crash became the worst railway accident in LIRR history, and one of the worst in the history of New York state.[22][23]

In 1964, the neighborhood gained news notoriety when Kitty Genovese was murdered near the Kew Gardens Long Island Railroad station. A New York Times article reported that none of the neighbors responded when she cried for help.[24] The story came to represent the apathy and anonymity of urban life. The circumstances of the case are disputed to this day. It has been alleged that the critical fact reported by The New York Times that "none of the neighbors responded" was false. The case of Kitty Genovese is an oft-cited example of the bystander effect, and the case that originally spurred research on this social psychological phenomenon.[25]

Land use

Kew Gardens remains a densely populated residential community, with a mix of one-family homes above the million-dollar range, complex apartments, co-ops and others converted and on the way or being converted as condominiums. A new hotel has been completed on 82nd Avenue, reflecting a modernization of the area. However, it is filled mainly with apartment buildings between four and ten stories high; while many are rentals, some are Housing cooperatives (co-ops). Although there are no New York City Housing Authority complexes in Kew Gardens, Mitchell-Lama buildings provide stabilized rental prices for families or individuals who may need help paying rent. On 83rd Avenue there is a 32-story Mitchell-Lama building. Along the borders of Richmond Hill, Briarwood, and Jamaica, smaller attached houses exist. Many of these are two or three family homes. Expensive single family homes are located around the Forest Park area. However, many owners are selling out their detached homes to developers who teardown and convert them into apartment housing or more expensive, lavish mini-estate houses. This has brought demographic change.

The neighborhood also has many airline personnel because of its proximity to the MTA's Q10 bus line to John F. Kennedy International Airport, as well as to Delta Air Lines and other airlines' special shuttles that serve pilots and flight attendants staying in Kew Gardens.

Kew Gardens's commercial center is Lefferts Boulevard between Austin Street and Metropolitan Avenue. Major attractions include the large sports bar Austin's Ale House, the Village Diner, Dani's Pizza, and Kew Gardens Cinemas, a 1930s art deco movie theater that has been converted into a six-screen multiplex and shows a mix of commercial, independent, and foreign films.[26] Lefferts is also home to the only bookstore in central Queens, Kew & Willow Books.[27]

Points of interest

Forest Park is the third largest park in Queens and is located to the south of Kew Gardens.[28] The Wisconsin Glacier retreated from Long Island some 20,000 years ago, leaving behind the hills that now are part of Forest Park.[29] The park was home to the Rockaway, Delaware and Lenape Native Americans until Dutch West India Company settlers arrived in 1634 and began establishing towns and pushing the tribes out.[30] The park contains the largest continuous oak forest in Queens.[31] Inside the park, the Forest Park Carousel was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004.[32]

In addition to Maple Grove Cemetery, the Ralph Bunche House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is also a designated National Historic Landmark.[32]

The county's civic center, Queens Borough Hall, along with one of the county criminal courts, stand at the northern end of the neighborhood, on Queens Boulevard, in a complex extending from Union Turnpike to Hoover Avenue. Adjacent to Borough Hall is a retired New York City Subway R33 (Redbird) which lays on a fake track as well as a platform. Visitors used to be able to go inside the car, but it was closed in 2015 due to lack of visitors.[33]

Demographics

Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of Kew Gardens was 23,278, a decrease of 610 (2.6%) from the 23,888 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 469.74 acres (190.10 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 49.6 inhabitants per acre (31,700/sq mi; 12,300/km2).[3]

The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 49.3% (11,478) White, 6.5% (1,515) African American, 0.2% (37) Native American, 15.6% (3,628) Asian, 0.0% (11) Pacific Islander, 1.1% (257) from other races, and 3.0% (701) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 24.3% (5,651) of the population.[4]

The entirety of Community Board 9, which comprises Kew Gardens, Richmond Hill, and Woodhaven, had 148,465 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 84.3 years.[34]:2, 20 This is higher than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[35]:53 (PDF p. 84)[36] Most inhabitants are youth and middle-aged adults: 22% are between the ages of between 0–17, 30% between 25–44, and 27% between 45–64. The ratio of college-aged and elderly residents was lower, at 17% and 7% respectively.[34]:2

As of 2017, the median household income in Community Board 9 was $69,916.[37] In 2018, an estimated 22% of Kew Gardens and Woodhaven residents lived in poverty, compared to 19% in all of Queens and 20% in all of New York City. One in twelve residents (8%) were unemployed, compared to 8% in Queens and 9% in New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 55% in Kew Gardens and Woodhaven, higher than the boroughwide and citywide rates of 53% and 51% respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018, Kew Gardens and Woodhaven are considered to be high-income relative to the rest of the city and not gentrifying.[34]:7

Demographic changes

The Hispanic and Asian populations in Kew Gardens have grown since the 2000 United States Census. At the time, the demographics were 66.2% White, 13.0% Asian, 7.0% African American, 0.3% Native American, and 7.4% of other races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 20.0% of the population.[38] Many of the residents are between the ages of 30 and 38, married, college graduates and renters.

Kew Gardens has the highest percentage of residents who work from home in Queens, with 4.5% of employed residents working from home.[39]

Kew Gardens is ethnically diverse. A large community of Jewish refugees from Germany took shape in the area after the Second World War which is reflected still today by the number of active synagogues in the area.[40] The neighborhood attracted many Chinese immigrants after 1965, about 2,500 Iranian Jews arrived after the Iranian Revolution of 1979,[41] and immigrants from China, Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan, Israel, the former Soviet Union, India, Bangladesh and Korea settled in Kew Gardens during the 1980s and 1990s. Currently, Kew Gardens has a growing population of Bukharian Jews from Uzbekistan, alongside a significant Orthodox Jewish community.[8] Also many immigrants from Central America, and South America call Kew Gardens home, as well as immigrants from Japan.

The increase of the Korean population followed the renovation and rededication of the First Church of Kew Gardens, which offers Korean-language services. In recent years, young professionals and Manhattanites looking for greenery, park-like atmosphere and spacious apartments have moved to the area.

Major development in the neighborhood, such as the construction of new apartment complexes and multi-family homes, has resulted in great demographic change as well. Immigrants from Latin America, Guyana, South Asia and East Asia, and the Middle East (especially Israel), have moved into these new developments. Even the local cuisine reflects this diversity in Kew Gardens, with Russian, Italian, Indian, Pakistani, and Uzbek dining available to residents and visitors. Many religious groups such as Jews, Muslims, and Hindus, can shop at local markets and bazaars that cater to their religious-food needs.

Economy

Kew Gardens has many locally owned businesses and restaurants especially on Lefferts Boulevard, Metropolitan Avenue, Austin Street, and Kew Gardens Road. The courthouse is very profitable, as is transportation to the area; however, neither profit the neighborhood directly, but instead serve as an incentive to move to the area. The cost of living in the neighborhood (as of 2015) is $62,900.[42] Pilots and flight attendants who stay in Kew Gardens in between John F. Kennedy International Airport and LaGuardia Airport flights also affect the local economy.

Saudi Arabian Airlines operates an office in Suite 401 at 80–02 Kew Gardens Road in Kew Gardens.[43]

Police and crime

Kew Gardens, Richmond Hill, and Woodhaven are patrolled by the 102nd Precinct of the NYPD, located at 87-34 118th Street.[5] The 102nd Precinct ranked 22nd safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010.[44] As of 2018, with a non-fatal assault rate of 43 per 100,000 people, Kew Gardens and Woodhaven's rate of violent crimes per capita is less than that of the city as a whole. The incarceration rate of 345 per 100,000 people is lower than that of the city as a whole.[34]:8

The 102nd Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 90.2% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct reported 2 murders, 24 rapes, 101 robberies, 184 felony assaults, 104 burglaries, 285 grand larcenies, and 99 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[45]

Fire safety

There are no fire stations in Kew Gardens itself, but the surrounding area contains two New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[46]

Health

As of 2018, preterm births are more common in Kew Gardens and Woodhaven than in other places citywide, though births to teenage mothers are less common. In Kew Gardens and Woodhaven, there were 92 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 15.7 births to teenage mothers per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide).[34]:11 Kew Gardens and Woodhaven have a higher than average population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 14%, slightly higher than the citywide rate of 12%.[34]:14

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Kew Gardens and Woodhaven is 0.0073 milligrams per cubic metre (7.3×10−9 oz/cu ft), less than the city average.[34]:9 Eleven percent of Kew Gardens and Woodhaven residents are smokers, which is lower than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers.[34]:13 In Kew Gardens and Woodhaven, 23% of residents are obese, 14% are diabetic, and 22% have high blood pressure—compared to the citywide averages of 22%, 8%, and 23% respectively.[34]:16 In addition, 22% of children are obese, compared to the citywide average of 20%.[34]:12

Eighty-six percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is about the same as the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 78% of residents described their health as "good," "very good," or "excellent," equal to the city's average of 78%.[34]:13 For every supermarket in Kew Gardens and Woodhaven, there are 11 bodegas.[34]:10

The nearest major hospitals are Long Island Jewish Forest Hills and Jamaica Hospital.[49]

Post offices and ZIP Code

Kew Gardens is covered by the ZIP Code 11415.[50] The United States Post Office operates two post offices nearby:

Education

Kew Gardens and Woodhaven generally have a lower rate of college-educated residents than the rest of the city as of 2018. While 34% of residents age 25 and older have a college education or higher, 22% have less than a high school education and 43% are high school graduates or have some college education. By contrast, 39% of Queens residents and 43% of city residents have a college education or higher.[34]:6 The percentage of Kew Gardens and Woodhaven students excelling in math rose from 34% in 2000 to 61% in 2011, and reading achievement rose from 39% to 48% during the same time period.[53]

Kew Gardens and Woodhaven's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is less than the rest of New York City. In Kew Gardens and Woodhaven, 17% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, lower than the citywide average of 20%.[34]:6[35]:24 (PDF p. 55) Additionally, 79% of high school students in Kew Gardens and Woodhaven graduate on time, more than the citywide average of 75%.[34]:6

Schools

Schools of note located in Kew Gardens include Yeshiva Tifereth Moshe, Bais Yaakov of Queens and Yeshiva Shaar Hatorah. The only public school in Kew Gardens is PS 99, which has special programs for gifted students such as the Gifted and Talented program.[54][55]

Libraries

The Queens Public Library operates two branches near Kew Gardens:

Transportation

The neighborhood is served by the New York City Subway's E, F, and <F> trains at the Kew Gardens–Union Turnpike subway station, and by the J and Z trains at the 121st Street subway station. In addition, Long Island Rail Road's City Terminal Zone stops at the Kew Gardens station.[58] New York City Bus routes include Q10, Q37, Q46, Q54 and Q60, as well as several express bus routes to Manhattan.[59]

The neighborhood is accessible by car from Interstate 678 (Van Wyck Expressway), Grand Central Parkway, Jackie Robinson Parkway, Queens Boulevard, and Union Turnpike. These all intersect at the Kew Gardens Interchange.[58]

Notable people

Notable residents of Kew Gardens include:

- Grace Albee (1890-1985), printmaker and wood engraver.[60]

- Burt Bacharach (born 1928) Award-winning pianist, composer and producer grew up in Kew Gardens.[61]

- Crosby Bonsall (1921–1995) artist and children's book author and illustrator.[62]

- Maud Ballington Booth (1865–1948), Volunteers of America co-founder.[63]

- Joshua Brand (born 1950), television writer, director and producer, grew up in Kew Gardens.[64]

- Ralph Bunche (1903–1971), diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner.[65]

- Rudolf Callmann (1892-1976), German American legal scholar and expert in the field of German and American competition law who assisted Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany.[66]

- Ron Carey (1936-2008), labor leader who served as president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters from 1991 to 1997.[67]

- Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977), actor, lived at 105 Mowbray Drive in 1919–1922.[68]

- Rodney Dangerfield (1921–2004), comedian who lived above the Austin Ale House.[69]

- Rona Elliot (born 1947), music journalist, grew up in Kew Gardens.[70]

- Lloyd Espenschied (1889-1986), electrical engineer who co-invented the modern coaxial cable.[71]

- George Gershwin (1898–1937), composer.[72]

- Bernhard Goetz (born 1947), best known for shooting four young black men on the subway in 1984.[73]

- Ladislav Hecht (1909-2004), Jewish professional tennis player, well known for representing Czechoslovakia in the Davis Cup during the 1930s.[74]

- Miriam Hopkins (1902–1972), actress.[75]

- Frederick Jagel (1897-1982), tenor, primarily active at the Metropolitan Opera in the 1930s and 1940s.[76]

- Rabbi Paysach Krohn (born 1945), rabbi and author, currently lives in Kew Gardens.[77]

- Norman Lewis (1915–2006), Olympic fencer

- Josef Lhevinne (1874–1944), concert pianist.[78][79]

- Rosina Lhévinne (1880-1976), pianist and pedagogue.[80]

- Robert H. Lieberman, filmmaker, grew up in Kew Gardens.[81]

- Saul Marantz (1911-1997), designed and built the first Marantz audio product at his home in Kew Gardens.[82]

- Peter Mayer (1936-2018), former Penguin Books CEO, grew up in Kew Gardens.[83]

- Anaïs Nin (1903–1977), author.[78]

- Dorothy Parker (1893–1967), poet.[72]

- Will Rogers, Sr. (1879–1935), actor.[72]

- Will Rogers, Jr. (1911–1993), congressman and son of Will Rogers, Sr.[68]

- Nelson Saldana, track cycling champion.[84]

- Ossie Schectman (1919-2013), basketball guard, who is credited with having scored the first basket in the Basketball Association of America (BAA), which would later become the National Basketball Association (NBA).[85]

- Robert Schimmel (1950-2010), comedian, grew up in Kew Gardens.[86]

- Jerry Springer (born 1944), talk show host and former mayor of Cincinnati, Ohio.[87]

- Paul Stanley (born 1952), musician, singer, songwriter and painter best known for being the rhythm guitarist and singer of the rock band Kiss.[88]

- Carol Montgomery Stone (1915-2011), actress and daughter of actor Fred Stone, grew up in Kew Gardens.[68]

- Sim Van der Ryn, architect, researcher and educator, who has applied principles of physical and social ecology to architecture and environmental design.[89]

- Dick Van Patten (1928-2015), actor, best known for his role on the television comedy-drama Eight Is Enough.[90]

- S. Howard Voshell (1888–1937), professional tennis player and later a promoter.[91]

- Robert C. Wertz (1932-2009), politician who served for 32 years as a member of the New York State Assembly.[92]

Gallery

Shops on Kew Gardens Road

Shops on Kew Gardens Road Queens Borough Hall

Queens Borough Hall P.S. 99 school annex

P.S. 99 school annex Kew Gardens Post Office

Kew Gardens Post Office A restaurant in Kew Gardens; the adjacent site would become a hotel

A restaurant in Kew Gardens; the adjacent site would become a hotel

See also

New York City portal

New York City portal

References

- "NYC Planning | Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Next to the L.I.R.R. Tracks; Five 2-Family Houses For Kew Gardens", The New York Times, April 24, 1994. Accessed August 27, 2018. "In 1909, when train service began on the Long Island Rail Road, the northerly section of the Man property was renamed Kew Gardens, also after a section of London."

- Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- "NYPD – 102nd Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- Current City Council Districts for Queens County, New York City. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- "New York Real Estate: Kew Gardens" Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, AM New York, August 28, 2008. Accessed July 4, 2009.

- Donovan, Aaron. "If You're Thinking of Living In/Kew Gardens, Queens; Small-Town Feeling at a Busy Crossroads", The New York Times, October 15, 2000. Accessed August 27, 2018.

- "LONG ISLAND ADDS LINKS; Grand Central Parkway And Extension Will Speed Traffic". The New York Times. July 9, 1933. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- "OFFICIALS INSPECT NEW CITY HIGHWAY; Park and Bridge Executives See Interborough Parkway, Soon to Be Ready". The New York Times. July 12, 1935. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Hirshon, Nicholas; Romano, Foreword by Ray (January 1, 2013). Forest Hills. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-9785-0.

-

- "New Subway Spurs Building on Queens Boulevard: Home Construction to $2,000,000 Value Now Going On, Says Boelsen" (PDF). New York Daily Star. April 17, 1930. p. 2. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Fulton History.

- "Million-Dollar Queens Borough Sale; Western Syndicate Buys Vacant Plots; Properties on the Line of the Jamaica Subway, Now Under Construction, and All Have Frontages on Queens Boulevard, Where Building Is Active". The New York Times. November 25, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Block Front Sold In Long Island City; Queens Boulevard Parcel Will Be Improved With Stores and Apartments. Elmhurst Sites TradedBuilders and Investors Active Along Route of Proposed Subway to Jamaica". The New York Times. May 24, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Sees Big Changes Coming In Queens ; Borough Has Bright Possibilities for Development, Says Fred G. Randall. Traffic Is Chief Factor Queens Boulevard Areas Showing Marked Activity—Realty Values Advancing". The New York Times. May 19, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Queens To Have 15-Story House; Tall Structure for New Residential Development in Forest Hills Area. Near Boulevard Subway Several Blocks Rezoned for High Buildings Between Jamaica and Kew Gardens. Apartment Height's Increase". The New York Times. March 23, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- Copquin, Claudia Gryvatz (January 1, 2007). The Neighborhoods of Queens. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11299-8.

-

- "Demand Is Noted For Queens Homes; Sales in Many Areas Exceed Summer Expectations of Developers; Jamaica Section Active; Buying Interest Reported at Kew Gardens—Open Roslyn Community Today Kew Gardens Activity Open Home Center at Roslyn". The New York Times. July 18, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- Myers, Steven Lee (June 14, 1992). "Life Beyond the Subway Is Subject to Its Own Disruptions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Forest Hills Is Active; Renting Is Heaviest in Years There, Broker Reports". The New York Times. September 11, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "New Queens Subway Stimulating Growth; Work Now Under Way to Kew Gardens—Many Home Communities Well Populated". The New York Times. April 26, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Subway Link Aids Realty Activity; Broker Notes the Expansion of Housing Facilities in Queens District". The New York Times. March 7, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- Roger P. Roess; Gene Sansone (August 23, 2012). The Wheels That Drove New York: A History of the New York City Transit System. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-3-642-30484-2.

-

- "PWA Party Views New Subway Link: Queens Section to Be Opened Tomorrow Is Inspected by Tuttle and Others" (PDF). nytimes.com. The New York Times. December 30, 1936. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- "Reproduction Poster of Extension to Union Turnpike – Kew Gardens". Flickr. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- Seyfried, Vincent F. (1995). Elmhurst : from town seat to mega-suburb. Vincent F. Seyfried.

-

- "Subway Link Aids Realty In Queens; Civic Leaders Urge Careful Planning for the Future Growth of District. Apartment Trend Seen Rising Values Are Predicted for the Forest Hills and Kew Gardens Areas. Views Future With Optimism Cites New Responsibilities Subway Link Aids Realty In Queens Changing Conditions Seen Sales in Rego Park". The New York Times. January 3, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Forest Hills Rentals; Demand There and in Kew Gardens Higher Than Last Year". The New York Times. July 11, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Residential Areas In Queens Expand; Plans Are Announced for New Garden Apartment House in Jackson Heights. Many Small Homes Built Queens Boulevard Values Rise-- Construction Activity Reported in Woodhaven Section. Queens Boulevard Values Rise". The New York Times. May 11, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- Dougherty, Philip H. (March 10, 1965). "Queens Boulevard, Once Just a Good Route to Jamaica, Is Becoming a 'Golden Area'; Urban Togetherness". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- Doyle, Dennis. "Long Island Rail Road's Worst Train Crash- The Richmond Hill Historical Society". Richmond Hill Historical Society. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- Furfaro, Danielle; Italiano, Laura (September 19, 2017). "This horrific, deadly train wreck sparked the creation of the MTA". New York Post. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- A Picture History of Kew Gardens, NY – Kitty Genovese – The popular account of the Kitty Genovese murder is mostly wrong as shown by the evidence from her killer's trial and other sources Archived April 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Dowd, Maureen. "20 Years After The Murder Of Kitty Genovese, The Question Remains: Why?", The New York Times, March 12, 1984. Accessed August 27, 2018.

- "Cinema Treasures- Kew Gardens Cinemas", November 2017. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- "Kew Gardens to Get Its First Bookstore in Decades" Archived November 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, May 2017. Accessed May 24, 2017.

- "NYC Parks FAQ".

- "Forest Park : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 26, 1939. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- "The Top 10 Secrets of Forest Park in Queens, NYC". Untapped Cities. November 2, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- "The Top 10 Secrets of Forest Park in Queens, NYC". Untapped Cities. November 2, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Barca, Christopher (July 16, 2015). "Tourist site closes over lack of tourists". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "Kew Gardens and Woodhaven (Including Kew Gardens, Ozone Park, Richmond Hill and Woodhaven)" (PDF). nyc.gov. NYC Health. 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- "2016-2018 Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan: Take Care New York 2020" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- "New Yorkers are living longer, happier and healthier lives". New York Post. June 4, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- "NYC-Queens Community District 9--Richmond Hill & Woodhaven PUMA, NY". Census Reporter. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- "Kew Gardens—Quiet and Leafy Location" Archived October 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Queens Chronicle, June 12, 2008. Accessed July 4, 2009.

- "Working From Home in Queens, NYC". The Austin Space. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- "Kew Gardens full of life. Population boost from immigrants". New York Daily News. September 16, 1999. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Danyluk, Harry (August 11, 1981). "Iranian Jews are building new temple in Kew Gardens". New York Daily News. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- http://www.realtor.com/local/Kew-Gardens_New-York_NY

- "Ministry Addresses in the U.S. Archived 3 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine." Embassy of Saudi Arabia Washington D.C. Accessed on January 5, 2008.

- "Woodhaven, Richmond Hills, and Kew Gardens – DNAinfo.com Crime and Safety Report". www.dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- "102nd Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- "FDNY Firehouse Listing – Location of Firehouses and companies". NYC Open Data; Socrata. New York City Fire Department. September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- "Engine Company 305/Ladder Company 151". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "Squad 270/Division 13". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Finkel, Beth (February 27, 2014). "Guide To Queens Hospitals". Queens Tribune. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "Zip Code 11415, Kew Gardens, New York Zip Code Boundary Map (NY)". United States Zip Code Boundary Map (USA). Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- "Location Details: Kew Gardens". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "Location Details: Borough Hall". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "Kew Gardens / Woodhaven – QN 09" (PDF). Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- "P.S. 99 Kew Gardens School", InsideSchools, September 2006. Accessed July 4, 2009.

- "P.S. 099 Kew Gardens". New York City Department of Education. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- "Branch Detailed Info: Richmond Hill". Queens Public Library. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "Branch Detailed Info: Briarwood". Queens Public Library. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "MTA Neighborhood Maps: neighborhood". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "The Professionalization of An American Woman Printmaker: The Early Career of Grace Albee, 1915 – 1934", Georgetown University Library, March 22, 2005. Accessed November 28, 2017. "These graphic works, created between 1915 and 1983, record her careful observations of her surroundings near the various locales in which she lived: Providence (1915–1928); Paris (1928–1933); New York City (1933–1938); Bucks County, Pennsylvania (1938–1962); Kew Gardens, New York (1962–1974); and finally in Barrington and Bristol, Rhode Island (1974–1983)."

- Cossar, Neil. "This Day in Music, May 12: Burt Bacharach, Neil Young; Burt Bacharach celebrates his 83rd birthday, Neil Young gets an eight-legged claim to fame.", The Morton Report, May 11, 2011. Accessed November 28, 2017. "The son of nationally syndicated columnist Bert Bacharach, Burt moved with his family in 1932 to Kew Gardens in Queens, New York. At his mother's insistence, he studied cello, drums, and then piano beginning at the age of 12."

- Staff. "Crosby Bonsall, 74, Children's Author", The New York Times, January 20, 1995. Accessed November 28, 2017. "She was born in Kew Gardens, Queens, and studied at the New York University School of Architecture and the American School of Design."

- "Gift To Maud B. Booth.; Charles D. Stickney Leaves Residuary Estate to Head of Volunteers.", The New York Times, March 31, 1916. Accessed July 5, 2009. "Charles Dickinson Stickney, a prominent lawyer of this city, who died on March 8, did not provide in his will for twelve first cousins, two second cousins, and one aunt, but bequeathed his entire residuary estate to Mrs. Maud Booth, widow of Ballington Booth and head of the Volunteers of America, who lives in Kew Gardens, L.I."

- Chan, Sewell. "Nazi Refugees’ Son Explores Complex Feelings", New York Times, April 22, 2009. Accessed July 5, 2009. "Growing up in Kew Gardens, Queens, in the 1940s and '50s, the children of Jewish refugees from Central Europe did not always feel different...Joshua Brand, the writer and producer, a creator of the television hits "St. Elsewhere" and "Northern Exposure"; the architectural historian Barry Lewis."

- Rimer, Sara. "From Queens Streets, City Hall Seems Very Distant", The New York Times, October 19, 1989. Accessed November 28, 2017. "But in Kew Gardens, a man had to be an Under Secretary General of the United Nations and a Nobel Prize winner to get his street cleared. 'Only one street in the entire community was plowed - Ralph Bunche's street,' said Rabbi Bernard Rosensweig, whose home is not on that now-legendary street where the late Mr. Bunche lived."

- Staff. "Rudolph Callmann, 83, Dies; Lawyer Aided Jewish Refugees", The New York Times, March 15, 1976. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Dr. Rudolf Callmann, lawyer, author and a leader in aiding Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, died Friday at his home in Kew Gardens, Queens. He was 83 years old."

- McFaden, Robert D. "New Teamster Chief's Motto: Honest Work for Honest Pay", The New York Times, December 15, 1991. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Mr. Carey, a former marine and a father of five who buys his suits off the rack, eats tuna sandwiches for lunch, drives a 1989 car and has lived in the same Kew Gardens house for 35 years, is a man who shuns extravagance, stays at budget hotels, carries his own suitcases, accounts for every penny of his expenses and for years has gone daily to the yards to talk to members."

- Hart, May Gleason. "Kew Gardens of Today – A Far Cry from 50 years Ago", Community News, January 1966. Accessed July 5, 2009. "We have had many prominent people reside in Kew Gardens. Wil [sic] Rogers and his family lived on the opposite corner. Will Rogers, Jr., Mary and Jimmie were my daughter Jeanne's play and schoolmates and were frequently joined by Paula and Carol Stone, daughters of the famous musical comedy star, Fred Stone."

- Christon, Lawrence. "The Education Of Rodney Dangerfield", Los Angeles Times, July 1, 1986. Accessed April 1, 2008. "Perhaps school talk reminded him of growing up in New York's Kew Gardens, where, as a boy named Jacob Cohen, he had an entertainer father who didn't use the family name (he billed himself as Phil Roy and when Dangerfield went into show business as a comedian, he used the moniker Jack Roy)."

- Chan, Sewell. "Nazi Refugees’ Son Explores Complex Feelings", New York Times, April 22, 2009. Accessed July 5, 2009. "Growing up in Kew Gardens, Queens, in the 1940s and '50s, the children of Jewish refugees from Central Europe did not always feel different...the pop music critic Rona Elliot; Joshua Brand, the writer and producer, a creator of the television hits "St. Elsewhere" and "Northern Exposure"; the architectural historian Barry Lewis; and, to be sure, countless lawyers and doctors."

- Cook, Joan. "Lloyd Espnschied, One Of The Inventors Of The Coaxial Cable", The New York Times, July 4, 1986. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Lloyd Espenschied, co-inventor of the coaxial cable, which paved the way for television transmission, died June 21 at a nursing home in Holmdel, N.J. He was 97 years old and lived in Kew Gardens, Queens."

- Bortolot, Lana. "New York Real Estate: Kew Gardens, Queens" Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, AM New York, August 28, 2008. Accessed July 5, 2009. "The neighborhood's nickname, "Crew Gardens," is a nod to the many airline personnel living here, but Kew Gardens has always been home to the jet set: Charlie Chaplin, Will Rogers, Dorothy Parker and George Gershwin were among the artistic community that settled here in the 1920s."

- McFadden, Robert D. "Goetz: A Private Man In A Public Debate", The New York Times, January 6, 1985. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Bernhard Hugo Goetz was born at Kew Gardens Hospital in Queens on Nov. 7, 1947, the youngest of four children of Bernhard Willard and Gertrude Goetz."

- Litsky, Frank. "Ladislav Hecht, 94, a Tactician On the Tennis Courts in the 30s", The New York Times, June 10, 2004. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Ladislav Hecht, once the captain of Czechoslovakia's Davis Cup team and perhaps the best tennis player on the European continent immediately before World War II, died May 27 at home in Kew Gardens, Queens. He was 94."

- Lewis, Barry. "Kew Gardens: Urban Village in the Big City", April 30, 1999. Accessed July 5, 2009. "Kew Gardens, a village in Queens about twelve miles (19 km) from Manhattan, has been home to movie stars and Broadway performers (Charlie Chaplin, Miriam Hopkins, and Will Rogers), authors (Anaïs Nin and Dorothy Parker), and even Nobel Prize winners (Ralph Bunche). In many ways it has been a community ahead of its time."

- Staff. "Jagel, Opera Tenor, Is Injured By Auto; Young Metropolitan Singer's Leg Fractured in Accident at Kew Gardens.", The New York Times, December 6, 1930. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Frederick Jagel, the young Metropolitan Opera Company tenor, who rose quickly to fame after his debut four seasons ago, received a multiple fracture of the left leg yesterday afternoon when he was knocked down by an automobile near his home in Kew Gardens while he was crossing Union Turnpike at Queens Boulevard"

- "The Mohel", July 2009. Accessed July 5, 2009. "He lives in Kew Gardens, NY with his wife Miriam and takes great pride in his family."

- "Neighborhood at Risk: Kew Gardens" Archived April 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Historic Districts Council, July 2009. Accessed July 5, 2009. "Kew Gardens became the home of an artistic and intellectual set. In the 1910s and 1920s, neighbors included film and stage stars, writers, musicians, and artists such as Charlie Chaplin, Will Rogers, Anaïs Nin, Dorothy Parker, Joseph Lhevinne, and George Gershwin."

- "Josef Lhevihhe, 69, Noted Pianist, Dies; Won Wide Acclaim as Soloist and in Recitals With Wife--Made Debut in Moscow at 14", The New York Times, December 3, 1944. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Josef Lhevinne, the pianist, died yesterday afternoon of a heart attack ailment in his home at 119-19 Eighty-third Avenue, Kew Gardens, Queens."

- Gottlieb, Jane. "Rosina Lhévinne 1880-1976", Jewish Women's Archive. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Immediately after the war, the Lhévinnes immigrated to the United States and settled in Kew Gardens, Queens. In 1924, both were invited to join the faculty of the newly established Juilliard Graduate School."

- Chan, Sewell. "Nazi Refugees’ Son Explores Complex Feelings", New York Times, April 22, 2009. Accessed July 5, 2009. "Growing up in Kew Gardens, Queens, in the 1940s and '50s, the children of Jewish refugees from Central Europe did not always feel different...Such are the themes of "Last Stop Kew Gardens," a 54-minute semiautobiographical documentary by Robert H. Lieberman, 68, a senior lecturer in physics at Cornell who has branched out into novels and films."

- Johnson, Lawrence B. "Saul B. Marantz, 85, Pioneer In Hi-Fi Audio Components", The New York Times, January 23, 1997. Accessed August 7, 2016. "After service in the Army during World War II, Mr. Marantz and his wife, Jean Dickey Marantz, settled in Kew Gardens, Queens."

- Chan, Sewell. "Nazi Refugees’ Son Explores Complex Feelings", New York Times, April 22, 2009. Accessed July 5, 2009. "Michael Nussbaum, a lawyer, and Peter Mayer, the former chief executive of Penguin Books, both recall their acute embarrassment about their German-speaking parents, who sounded just like the Nazis in postwar American films."

- Staff. "Animal, Guv, Rabbit and Hartnett join Hall; L.V. Velodrome welcomes four riders to the Class of 2006.", The Morning Call, August 17, 2006. Accessed November 28, 2017. "From Kew Gardens, N.Y., Nelson "The Rabbit" Saldana marked a dominant cycling career that began in 1969 with an intermediate national championship victory and featured a gold medal at the 1975 Pan American Games in the Team Pursuit."

- "Ossie Schechtman, scored first basket in NBA, dies at 94", Jewish Telegraphic Agency, July 30, 2013. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Schechtman, a 6-foot guard from Kew Gardens in Queens, starred at Long Island University, guiding the Blackbirds to an undefeated 1938-39 season and titles in the NIT and NCAA tournaments."

- Krawitz, Alan. "Kew Gardens — Quiet And Leafy Location" Archived October 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Queens Chronicle, June 12, 2008. Accessed July 5, 2009. "Notable former residents of Kew Gardens include Will Rogers and most recently daytime talk host Jerry Springer. In addition, Kew Gardens has been the subject of numerous books and films, including Barry Lewis' 1999 book, "Kew Gardens: Urban Village in the Big City," and Robert Lieberman's film "Last Stop Kew Gardens," featuring Springer, Josh Brand and comedian Robert Schimmel."

- Colangelo, Lisa L. "Springer's A Class Act Ps 99 Honors Famed Alum At 75th Anniversary Gala", New York Daily News, December 6, 1999. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Jerry Springer still remembers the morning his parents sent him off to school and begged him to behave. It was open school day at Public School 99 in Kew Gardens, and the rest of his fifth-grade class would be sitting with their parents."

- Leaf, David; and Sharp, Ken. KISS: Behind the Mask - Official Authorized Biography, p. 25. Grand Central Publishing, 2008. ISBN 9780446553506. Accessed November 28, 2017. "In 1960, the Eisen family moved to Kew Gardens in Queens, not too far away from where the Klein family was living."

- Sim Van der Ryn (Architect), Pacific Coast Architecture Database. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Van der Ryn left Holland during World War II, living first in the Kew Gardens neighborhood of Queens, NY, and then moved to Great Neck, NY, also on Long Island."

- Colker, David. "Dick Van Patten dies at 86; 'Eight is Enough' star, pet food firm co-founder", Los Angeles Times, June 23, 2015. Accessed November 28, 2017. "He was born on Dec. 9, 1928, in the Kew Gardens neighborhood of Queens in New York City."

- Staff. "S. Howard Voshell, Ex-Tennis Star, 49; National Indoor Champion in 1917 and 1918 Succumbs at Home in Kew Gardens", The New York Times, November 11, 1937. Accessed November 28, 2017. "S. Howard Voshell, a former "first ten" man in the national tennis ranking, who held the national indoor championship in 1917 and 1918, died yesterday at his home, 32 Abingdon Road, Kew Gardens, Queens, after an illness of six months."

- Brand, Rick. "Robert Wertz, longtime GOP assemblyman, dead at 76", Newsday, May 5, 2009. Accessed November 28, 2017. "Born in Kew Gardens, Queens, Wertz graduated from Sewanhaka High School in Floral Park and got a bachelor's degree from upstate Alfred University and a law degree from Albany Law School."

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kew Gardens, Queens. |