Kritosaurus

Kritosaurus is an incompletely known genus of hadrosaurid (duck-billed) dinosaur. It lived about 74.5-66 million years ago, in the Late Cretaceous of North America. The name means "separated lizard" (referring to the arrangement of the cheek bones in an incomplete type skull), but is often mistranslated as "noble lizard" in reference to the presumed "Roman nose" [1] (in the original specimen, the nasal region was fragmented and disarticulated, and was originally restored flat).

| Kritosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| K. navajovius holotype skull, AMNH | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Saurolophinae |

| Tribe: | †Kritosaurini |

| Genus: | †Kritosaurus Brown, 1910 |

| Type species | |

| †Kritosaurus navajovius Brown, 1910 | |

| Species | |

|

†K. navajovius Brown, 1910 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Anasazisaurus? Hunt & Lucas, 1993 | |

History of discovery

In 1904, Barnum Brown discovered the type specimen (AMNH 5799) of Kritosaurus near the Ojo Alamo Formation, San Juan County, New Mexico, United States, while following up on a previous expedition.[2] He initially could not definitely correlate the stratigraphy, but by 1916 was able to establish it as from what is now known as the late Campanian-age De-na-zin Member of the Kirtland Formation.[3][4] When discovered, much of the front of the skull had either eroded or fragmented, and Brown reconstructed this portion after what is now called Edmontosaurus, leaving out many fragments.[2] However, he had noticed that something was different about the fragments, but ascribed the differences to crushing.[5] He initially wanted to name it Nectosaurus, but found out that this name was already in use; Jan Versluys, who had visited Brown before the change, inadvertently leaked the previous choice.[6] He kept the specific name, though, leading to the combination K. navajovius.

The 1914 publication of the arch-snouted Canadian genus Gryposaurus[7] changed Brown's mind about the anatomy of his dinosaur's snout. Going back through the fragments, he revised the previous reconstruction and gave it a Gryposaurus-like arched nasal crest.[5] He also synonymized Gryposaurus with Kritosaurus,[8] a move supported by Charles Gilmore.[3] This synonymy was used through the 1920s (William Parks's designation of a Canadian species as Kritosaurus incurvimanus,[9] now considered a synonym of Gryposaurus notabilis[10]) and became standard after the publication of Richard Swann Lull and Nelda Wright's 1942 monograph on North American hadrosaurids.[11] From this time until 1990, Kritosaurus would be composed of at least the type species K. navajovius, K. incurvimanus, and K. notabilis, the former type species of Gryposaurus. The poorly known species Hadrosaurus breviceps (Marsh, 1889),[12] known from a dentary from the Campanian-age Judith River Formation of Montana, was also assigned to Kritosaurus by Lull and Wright,[11] but this is no longer accepted.[13][14]

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hadrosaurus had entered the discussion as a possible synonym of either Kritosaurus, Gryposaurus, or both, particularly in semi-technical "dinosaur dictionaries".[15][16] David B. Norman's The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, uses Kritosaurus for the Canadian material (Gryposaurus), but identifies the mounted skeleton of K. incurvimanus as Hadrosaurus.[17]

The synonymization of Kritosaurus and Gryposaurus that lasted from the 1910s to 1990 led to a distorted picture of what the original Kritosaurus material represented. Because the Canadian material was much more complete, most representations and discussions of Kritosaurus from the 1920s to 1990 are actually more applicable to Gryposaurus. This includes, for example, James Hopson's discussion of hadrosaur cranial ornamentation,[18] and the adaptation of this for the public in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs.[19]

Formerly assigned species and material

In 1984, Argentine paleontologist José Bonaparte and colleagues named Kritosaurus australis for hadrosaur bones from the late Campanian-early Maastrichtian Los Alamitos Formation of Rio Negro, Patagonia, Argentina.[20] This species is now thought to be a synonym of Secernosaurus koerneri.[21]

In 1990, Jack Horner and David B. Weishampel once again separated Gryposaurus, citing the uncertainty associated with the latter's partial skull. Horner in 1992 described two more skulls from New Mexico that he claimed belonged to Kritosaurus and showed that it was quite different from Gryposaurus,[22] but the following year Adrian Hunt and Spencer G. Lucas put each skull in its own genus, creating Anasazisaurus and Naashoibitosaurus.[23]

Adrian Hunt and Spencer G. Lucas, American paleontologists, named Anasazisaurus horneri in 1993. The name was derived from the Anasazi, an ancient Native American people, and the Greek word sauros ("lizard"). The Anasazi were famous for their cliff-dwellings, such as those in Chaco Canyon, near the location of fossil Anasazisaurus remains. The term "Anasazi" itself is actually a Navajo language word, anaasází ("enemy ancestors"). The species was named in honor of Jack Horner, the American paleontologist who first described the skull in 1992. The holotype skull (and only known specimen) was collected in the late 1970s by a Brigham Young University field party working in San Juan County, and is housed at BYU as BYU 12950.[23]

Horner originally assigned the Anasazisaurus skull to Kritosaurus navajovius,[22] but Hunt and Lucas could not find any diagnostic features in the limited material of Kritosaurus and judged the genus to be a nomen dubium. Since the Anasazisaurus skull did have diagnostic features of its own, and did not appear to them to share any unique features with Kritosaurus, it was given the new name Anasazisaurus horneri,[23] an opinion which was supported by some later authors.[13] Not all authors have agreed with this, Thomas E. Williamson in particular defending Horner's original interpretation,[4] and several subsequent studies recognized both distinct genera.[24][26]

A comprehensive study of known Kritosaurus material published by Albert Prieto-Márquez in 2013 upheld the status of Naashoibitosaurus as a distinct genus, but found that the type specimens of Kritosaurus and Anasazisaurus were indistinguishable when comparing overlapping elements (i.e. only those bones preserved in both specimens). Prieto-Márquez therefore regarded Anasazisaurus as a synonym of Kritosaurus, but retained it as the distinct species K. horneri.[25]

A partial skeleton from the Sabinas Basin in Mexico was described as Kritosaurus sp. by Jim Kirkland and colleagues,[24] but considered an indeterminate saurolophine by Prieto-Márquez (2013).[25] This skeleton is about 20% larger than other known specimens, around 11 meters [36 ft] long, and with a distinctively curved ischium, and represents the largest known well-documented North American saurolophine. Unfortunately, the nasal bones are also incomplete in the skull remains from this material.[24]

A possibly second but confirmed to be valid species of Kritosaurus may have lived in the Javelina Formation along side Kritosaurus navajovius.[27][28]

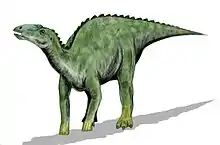

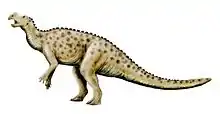

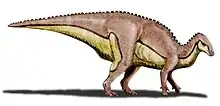

Description

The type specimen of Kritosaurus navajovius is only represented by a partial skull and lower jaws, and associated postcranial remains.[13] The greater portion of the muzzle and upper beak are missing.[24] The length of the skull is estimated at 87 centimeters (34 in) from the tip of the upper beak to the base of the quadrate that articulates with the lower jaw at the back of the skull.[29] Potential diagnostic characteristics of Kritosaurus include a predentary (lower beak) without tooth-like crenulations, a sharp downward bend to the lower jaws near the beak, and a heavy, somewhat rectangular maxilla (upper tooth-bearing bone).[24]

Based on the skull originally referred to Anasazisaurus, the form of the complete crest is that of a tab or flange of bone, from the nasals, that rises between and above the eyes and folds back under itself. This unique crest allows it to be distinguished from similar hadrosaurs, like Gryposaurus.[22] The top of the crest is roughened, and the maximum preserved length of the skull is ~90 centimeters (~35 in).[26]

According to Prieto-Márquez who re-diagnosed this genus in 2013, Kritosaurus can be distinguished based on the following characteristics: the length of the dorsolateral margin of the maxilla is extensive, the jugal features an orbital constriction that is deeper than the infratemporal one, the infratemporal fenestra is greater than the orbit and has a dorsal margin that is greatly elevated above the dorsal orbital margin in adults, the frontal bone is participating in the orbital margin, the presence of paired caudal parasagittal processes of the nasals resting over the frontal bones.[25]

In 2016, Paul estimated its length at 9 meters (30 feet) and its weight at 4 tonnes (4.4 short tons).[30] Holtz (2011) gives the same length.[31]

Classification

Kritosaurus was a hadrosaurine hadrosaurid, a flat-headed or solid-crested duckbill. Though many species and specimens have been referred to the genus in the past, most of them do not show the shared distinguishing characteristics to allow them to be considered part of the genus, or have been synonymized with other genera of hadrosaurs. The closest relative of Kritosaurus navajovius is Anasazisaurus horneri (or Kritosaurus horneri), which, together with close relatives such as Gryposaurus and Secernosaurus, form a clade called the Kritosaurini within the larger clade Saurolophinae.[25] Location and time separate Kritosaurus and the slightly older, primarily Canadian Gryposaurus, along with some cranial details.[24]

.JPG.webp)

The following is a cladogram based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Prieto-Márquez and Wagner in 2012, showing the relationships of Kritosaurus among the other Kritosaurini:[32]

| Kritosaurini |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

The nasal crest of Kritosaurus, whatever its true form, may have been used for a variety of social functions, such as identification of sexes or species and social ranking.[13] There may have been inflatable air sacs flanking it for both visual and auditory signaling.[18]

Diet and feeding

As a hadrosaurid, Kritosaurus would have been a large bipedal/quadrupedal herbivore, eating plants with a sophisticated skull that permitted a grinding motion analogous to chewing. Its teeth were continually replacing and packed into dental batteries that contained hundreds of teeth, only a relative handful of which were in use at any time. Plant material would have been cropped by its broad beak, and held in the jaws by a cheek-like organ. Feeding would have been from the ground up to ~4 meters (13 ft) above.[13] If it was a separate genus, how it would have partitioned resources with the similar and contemporaneous Naashoibitosaurus is unknown.

Paleoecology

Kritosaurus was discovered in the De-na-zin Member of the Kirtland Formation. This formation dates from the late Campanian stages of the Late Cretaceous Period (74 to 70 million years ago),[4] and is also the source of several other dinosaurs, like Alamosaurus, a species of Parasaurolophus, Pentaceratops, Nodocephalosaurus, Saurornitholestes, and Bistahieversor.[33] The Kirtland Formation is interpreted as river floodplains appearing after a retreat of the Western Interior Seaway. Conifers were the dominant plants, and chasmosaurine horned dinosaurs appear to have been more common than hadrosaurids.[34] The presence of Parasaurolophus and Kritosaurus in northern latitude fossil sites may represent faunal exchange between otherwise distinct northern and southern biomes in Late Cretaceous North America.[35] Both taxa are uncommon outside of the southern biome, where, along with Pentaceratops, they are predominate members of the fauna.[35]

The geographic range of Kritosaurus remains in North America was expanded by the discovery of bones from the late Campanian-age Aguja Formation of Texas, including a skull.[36][37] Additionally, a partial skull from Coahuila, Mexico has been referred to K. navajovius.[25]

Since the 1910s and 1930s, Barnum Brown described that an unsubscribed species of Kritosaurus, the most likely candidate being Kritosaurus navajovius, had inhabited the late Maastrichtian Ojo Alamo Formation, where the first specimen of Kritosaurus was unearthed, in New Mexico as well as the Javelina Formation and the El Picacho Formation in Texas, which was a flood plain type environment at the time of the Cretaceous.[2][38][39] Charles W. Gilmore also made notes about Brown's work surveys and finds from the Ojo Alamo Formation whilst doing research in the North Horn Formation in Utah as well as researching the Ojo Alamo Formation himself.[40][41] These fossils might be of an unknown species of hadrosaur or an undescribed specimen of Kritosaurus or Kritosaurus navajovius. However, not all of the paleontological community agrees with the age of the Kritosaurus holotype unearthed by Barnum Brown. This is due to the unconformity that divides the Ojo Alamo Formation into two parts; the older Naashoibito member, which overlies the Campanian era Kirtland Formation, and the younger Kimbeto member. Starting in the 2000s and 2010s, more research into this area as well as nearby fossil formations in neighboring states has brought more information about them to light. This issue will probably be resolved in the future.[42][43][44][45][46][47]

However, confirmed Kritosaurus remains, possibly belonging to K. navajovius, cf. K. navajovius, and possibly a new species have been unearthed in the Javelina Formation and the El Picacho Formation in Texas.[37][2][48][49][50] This genus lived alongside numerous species of dinosaurs including the sauropod Alamosaurus, the ceratopsians Bravoceratops, Ojoceratops, Torosaurus and a possible species of Eotriceratops, hadrosaurs which included a possible species of Edmontosaurus annectens, Saurolophus and Gryposaurus, Gryposaurus alsatei to be exact,[51] and the armored nodosaur Glyptodontopelta. Theropods from this environment which included Tyrannosaurus, smaller theropods like a species of Troodon and Richardoestesia, the oviraptorid Ojoraptorsaurus, the dromaeosaur Dineobellator, and indeterminate ornithomimids and other undescribed dromaeosaurs. Non-dinosaur species that had shared the same environment with Kritosaurus included the giant pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus, various species of fishes and rays, amphibians, lizards, turtles like Adocus, and multiple species of mammals like Alphadon and Mesodma.

See also

References

- Creisler, Benjamin S. (2007). "Deciphering duckbills". In Carpenter Kenneth (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 185–210. ISBN 978-0-253-34817-3.

- Brown, Barnum (1910). "The Cretaceous Ojo Alamo beds of New Mexico with description of the new dinosaur genus Kritosaurus". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28 (24): 267–274. hdl:2246/1398.

- Gilmore, Charles W. (1916). "Contributions to the geology and paleontology of San Juan County, New Mexico. 2. Vertebrate faunas of the Ojo Alamo, Kirtland and Fruitland Formations". United States Geological Survey Professional Paper. 98-Q: 279–302.

- Williamson, Thomas E. (2000). "Review of Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the San Juan Basin, New Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; Heckert A.B. (eds.). Dinosaurs of New Mexico. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 17. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 191–213.

- Sinclair, William J.; Granger, Walter (1914). "Paleocene deposits of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 33 (3): 297–316. Bibcode:1916JG.....24Q.305S. doi:10.1086/622336.

- Olshevsky, George (1999-11-17). "Re: What are these dinosaurs? 2: Return of What are these dinosaurs?". Dinosaur Mailing List. Archived from the original on 2011-11-17. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- Lambe, Lawrence M. (1914). "On Gryposaurus notabilis, a new genus and species of trachodont dinosaur from the Belly River Formation of Alberta, with a description of the skull of Chasmosaurus belli". The Ottawa Naturalist. 27 (11): 145–155.

- Brown, Barnum (1914). "Cretaceous Eocene correlation in New Mexico, Wyoming, Montana, Alberta". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 25 (1): 355–380. Bibcode:1914GSAB...25..355B. doi:10.1130/gsab-25-355. hdl:2246/704.

- Parks, William A. (1920). "The osteology of the trachodont dinosaur Kritosaurus incurvimanus". University of Toronto Studies, Geology Series. 11: 1–76.

- Prieto–Marquez, Alberto (2010). "The braincase and skull roof of Gryposaurus notabilis (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae), with a taxonomic revision of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (3): 838–854. doi:10.1080/02724631003762971. S2CID 83539808.

- Lull, Richard Swann; Wright, Nelda E. (1942). Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America. Geological Society of America Special Paper 40. Geological Society of America. pp. 164–172.

- Marsh, O.C. (1889). "Notice of new American Dinosauria". American Journal of Science. 38 (220): 331–336. Bibcode:1889AmJS...37..331M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-37.220.331. S2CID 131729220.

- Horner, John R.; Weishampel, David B.; Forster, Catherine A (2004). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Prieto-Márquez, Alberto; Weishampel, David B.; Horner, John R. (2006). "The dinosaur Hadrosaurus foulkii, from the Campanian of the East Coast of North America, with a reevaluation of the genus" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (1): 77–98.

- Glut, Donald F. (1982). The New Dinosaur Dictionary. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-8065-0782-8.

- Lambert, David; the Diagram Group (1983). A Field Guide to Dinosaurs. New York: Avon Books. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-380-83519-5.

- Norman, David. B. (1985). "Hadrosaurids I". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: An Original and Compelling Insight into Life in the Dinosaur Kingdom. New York: Crescent Books. pp. 116–121. ISBN 978-0-517-46890-6.

- Hopson, James A. (1975). "The evolution of cranial display structures in hadrosaurian dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 1 (1): 21–43. doi:10.1017/S0094837300002165.

- Norman, David B. (1985). "Hadrosaurids II". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: An Original and Compelling Insight into Life in the Dinosaur Kingdom. New York: Crescent Books. pp. 122–127. ISBN 978-0-517-46890-6.

- Bonaparte, José; Franchi, M.R.; Powell, J.E.; Sepulveda, E. (1984). "La Formación Los Alamitos (Campaniano-Maastrichtiano) del sudeste de Rio Negro, con descripcion de Kritosaurus australis n. sp. (Hadrosauridae). Significado paleogeografico de los vertebrados". Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina (in Spanish). 39 (3–4): 284–299.

- Prieto–Marquez, Alberto; Salinas, Guillermo C. (2010). "A re–evaluation of Secernosaurus koerneri and Kritosaurus australis (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (3): 813–837. doi:10.1080/02724631003763508. S2CID 85814033.

- Horner, John R. (1992). "Cranial morphology of Prosaurolophus (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae) with descriptions of two new hadrosaurid species and an evaluation of hadrosaurid phylogenetic relationships". Museum of the Rockies Occasional Paper. 2: 1–119.

- Hunt, Adrian P.; Lucas, Spencer G. (1993). "Cretaceous vertebrates of New Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; Zidek J. (eds.). Dinosaurs of New Mexico. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 2. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 77–91.

- Kirkland, James I.; Hernández-Rivera, René; Gates, Terry; Paul, Gregory S.; Nesbitt, Sterling; Serrano-Brañas, Claudia Inés; Garcia-de la Garza, Juan Pablo (2006). "Large hadrosaurine dinosaurs from the latest Campanian of Coahuila, Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; Sullivan Robert M. (eds.). Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 35. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 299–315.

- Prieto-Márquez, A (2013). "Skeletal morphology of Kritosaurus navajovius (Dinosauria:Hadrosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of the North American south-west, with an evaluation of the phylogenetic systematics and biogeography of Kritosaurini". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 12 (2): 133–175. doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.770417. S2CID 84942579.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Spielman, Justin A.; Sullivan, Robert M.; Hunt, Adrian P.; Gates, Terry (2006). "Anasazisaurus, a hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of New Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; Sullivan Robert M. (eds.). Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 35. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 293–297.

- Wagner, Jonathan R. (May 2001). "The hadrosaurian dinosaurs (ornithiscia: hadrosauria) of Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas, with implications for late Cretaceous paleozoogeography". Doctoral Dissertation, Texas Tech University. hdl:2346/11160. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- Lehman, Thomas M.; Wick, Steve L.; Wagner, Jonathan R. (1 July 2016). "Hadrosaurian dinosaurs from the Maastrichtian Javelina Formation, Big Bend National Park, Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 1 (2): 333–356. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.48. S2CID 133329640. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Lull, Richard Swann; Wright, Nelda E. (1942). Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America. Geological Society of America Special Paper 40. Geological Society of America. p. 226.

- Paul, G.S., 2016, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, second edition, Princeton University Press p. 340

- https://www.geol.umd.edu/~tholtz/dinoappendix/HoltzappendixWinter2011.pdf

- Prieto-Márquez, A.; Wagner, J.R. (2012). "Saurolophus morrisi, a new species of hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Pacific coast of North America" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. in press. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0049. S2CID 55969908. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-05.

- Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loeuff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth, M.P.; and Noto, Christopher R. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution". The Dinosauria (2nd). 517–606.

- Russell, Dale A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press, Inc. pp. 160–164. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- Lehman, T. M., 2001, Late Cretaceous dinosaur provinciality: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 310-328.

- Sankey, Julia T. (2001). "Late Campanian southern dinosaurs, Aguja Formation, Big Bend, Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 75: 208–215. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2001)075<0208:LCSDAF>2.0.CO;2.

- Wagner, Jonathan R.; Lehman, Thomas M. (2001). "A new species of Kritosaurus from the Cretaceous of Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (3, Suppl): 110A–111A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2001.10010852. S2CID 220414868.

- Wagner, Jonathan R. (May 2001). "The hadrosaurian dinosaurs (ornithiscia: hadrosauria) of Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas, with implications for late Cretaceous paleozoogeography". Doctoral Dissertation, Texas Tech University. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Osmólska, Halszka; Dobson, Peter; Weishampel, David B. (6 November 2004). The Dinosauria. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 582. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Gilmore, Charles Whitney (1916). "Vertebrate faunas of the Ojo Alamo, Kirtland and Fruitland formations" (PDF). Washington D.C.: US Government Printing Office: 280–302. Retrieved 17 November 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gilmore, Charles Whitney (1946). Reptilian Fauna of the North Horn Formation of Central Utah. Vol. 210 (PDF). Washington D.C.: UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. pp. 29–52. doi:10.3133/PP210C. S2CID 128849169. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G. (2003). Lucas, Spencer G.; Semken, Steven C.; Berglof, William; Ulmer-Scholle, Dana (eds.). "The Kirtlandian, a new land-vertebrate "age" for the Late Cretaceous of western North America" (PDF). Geology of the Zuni Plateau. New Mexico Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources 801 Leroy Place Socorro, NM 87801-4796: New Mexico Geological Society: 369–377. Retrieved 17 November 2020.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Sullivan, Robert M. (2004). "THE KIRTLANDIAN LAND-VERTEBRATE "AGE"—LATE CRETACEOUS OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 36 (4).

- Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G. (2006). "The Kirtlandian land-vertebrate "age"–faunal composition, temporal position and biostratigraphic correlation in the nonmarine Upper Cretaceous of western North America". Bulletin - New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. 1801 Mountain Rd NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104: New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science: 7–29. ISSN 1524-4156. Retrieved 17 November 2020.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Roberts, Eric M.; Deino, Alan L.; Chan, Marjorie A. (April 2005). "40Ar/39Ar age of the Kaiparowits Formation, southern Utah, and correlation of contemporaneous Campanian strata and vertebrate faunas along the margin of the Western Interior Basin". Cretaceous Research. 26 (2): 307–318. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2005.01.002. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Jasinski, Steven E.; Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G. (January 2011). "Taxonomic composition of the Alamo Wash local fauna from the Upper Cretaceous Ojo Alamo Formation (Naashoibito Member), San Juan Basin, New Mexico". Fossil Record. 3: 216–271. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Williamson, Thomas W. (2000). Lucas, S. G.; Heckert, A. B. (eds.). "Review of Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the San Juan Basin, New Mexico." Dinosaurs of New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin. 1801 Mountain Rd NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. 17: 191–213.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Wagner, Jonathan R. (May 2001). "The hadrosaurian dinosaurs (ornithiscia: hadrosauria) of Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas, with implications for late Cretaceous paleozoogeography". Doctoral Dissertation, Texas Tech University. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Osmólska, Halszka; Dobson, Peter; Weishampel, David B. (6 November 2004). The Dinosauria. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 582. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Lehman, Thomas M.; Wick, Steve L.; Wagner, Jonathan R. (1 July 2016). "Hadrosaurian dinosaurs from the Maastrichtian Javelina Formation, Big Bend National Park, Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 1 (2): 333–356. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.48. S2CID 133329640. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Lehman, Thomas M.; Wick, Steve L.; Wagner, Jonathan R. (1 July 2016). "Hadrosaurian dinosaurs from the Maastrichtian Javelina Formation, Big Bend National Park, Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 1 (2): 333–356. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.48. S2CID 133329640. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

External links

Media related to Kritosaurus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kritosaurus at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)