Lê Thánh Tông

Lê Thánh Tông (Hán tự: 黎聖宗; 25 August 1442 – 3 March 1497), personal name Lê Hạo, temple name Thánh Tông, courtesy name Tư Thành, was the emperor of Đại Việt from 1460 to 1497, the fifth monarch of the House of Lê and is one of the greatest monarchs in Vietnamese history. His era was eulogized as the Prospered reign of Hồng Đức.

| Lê Thánh Tông 黎聖宗 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor of Đại Việt | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 5th Emperor of the Le Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 26 June 1460 – 3 March 1497 (36 years, 250 days) | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Lê Nghi Dân | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Lê Hiến Tông | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | Lê Tư Thành (黎思誠) 25 August 1442 | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 3 March 1497 (aged 54) | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Chiêu Tomb, Lam Kinh, Đại Việt | ||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Nguyễn Thị Huyên | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | House of Lê | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Lê Thái Tông | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Ngô Thị Ngọc Dao | ||||||||||||||||

| Personal name | |

| Vietnamese | Lê Hạo |

|---|---|

| Hán-Nôm | 黎灝 |

| Temple name | |

| Vietnamese alphabet | Lê Thánh Tông |

|---|---|

| Hán-Nôm | 黎聖宗 |

| Lê dynasty monarchs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early life

Lê Thánh Tông's birth name is Lê Hạo (黎灝), courtesy name Tư Thành (思誠), pseudonym Đạo Am chủ nhân (道庵主人), rhymed name Tao Đàn nguyên súy (騷壇元帥), formal title Thiên Nam động chủ (天南洞主), was the fourth son of emperor Lê Thái Tông and his consort Ngô Thị Ngọc Dao. He was the fourth grandson of Lê Lợi,[1] the half-brother of Lê Nhân Tông and it is likely that his mother and consort Nguyễn Thị Anh (the mother of Lê Nhân Tông) were related (cousins or perhaps sisters). When Hạo was three years old, he was brought to the royal palace and was educated just like his half brother, the ruling emperor Lê Nhân Tông, and other brothers, Lê Khắc Xương and Lê Nghi Dân in Hanoi.[2] When his elder half brother, Lê Nghi Dân, staged a coup and killed the emperor and the queen in late 1459, Prince Hạo was spared.[3] Nghi Dân proclaimed himself emperor. Nine months later, a second counter-coup against Lê Nghi Dân led by two military leaders Nguyễn Xí and Đinh Liệt successfully carried out, and Nghi Dân was killed in the royal palace.[3] The plotters asked Prince Hạo to become the new emperor and he accepted. Two days after Lê Nghi Dân’s death, Lê Hạo was proclaimed emperor.[3]

The leaders of the counter-coup which removed and killed Nghi Dân were two of the last surviving friends and aides of Lê Lợi - Nguyễn Xí and Đinh Liệt. The pair had been out of power since the 1440s, but they still commanded respect due to their association with the dynasty's founder, Lê Lợi. The new emperor appointed these men to the highest positions in his new government: Nguyễn Xí became one of the emperor's councilors, and Đinh Liệt was gifted command over the royal army of Đại Việt.

Reign

Bureaucratic reforms

His reforms were designed to replace the Thanh Hoá oligarchy of Dai Viet's southern region with a corps of bureaucrats selected through the Confucian civil service examinations.[4]

Following the Chinese model, Lê Thánh Tông divided the government into six ministries; they were Finance, Rites, Justice, Personnel, Army, and Public Works.[5] Nine grades of rank were set up for both the civil administration and the military.[1] A Board of Censors was set up with royal authority to monitor governmental officials and reported exclusively to the emperor. However, governmental authority did not extend all the way to the village level.[6] The villages were ruled by their own councils.[6]

In 1469, all of Dai Viet was mapped and a full census was taken, listing all the villages in the kingdom. Around this time the country was divided into 13 dao (provinces).[7] Each was administrated by a Governor, Judge, and the local army commander. Thánh Tông also ordered that a new census should be taken every six years.[8] Other public works that were undertaken included building and repair of granaries, using the army to rebuild and repair irrigation systems after floods, and sending out doctors to areas afflicted by outbreaks of disease. Even though the emperor, at 25, was relatively young, he had already restored Vietnam's stability, which was a marked contrast from the turbulent times marking the reigns of the two emperors before him. By 1471, the kingdom employed more than 5,300 officials (0.1 percent of the population), equally divided between the court and the provinces, with at least one supervising officer every three villages.[8]

A national-wide census was conducted in 1490, reported approximately 8,000 village-level jurisdictions throughout the country including the thirty-six urban wards that lay between the royal compound and the Red River at Dong Kinh, the only city in the country;[9][10] with the total population was approximately 4.4 million people, the Red River delta had been the most densely inhabited region of Southeast Asia in the early-modern era.[11][12]

The new government proved to be effective and represented a successful adaptation of the Chinese Confucian system of government outside of China. However, following the deaths of Thánh Tông and of his son and successor, Lê Hiến Tông (r. 1498–1504), this new model of government crashed not once but twice in the next three following centuries.[1]

Legal reforms and a new national law

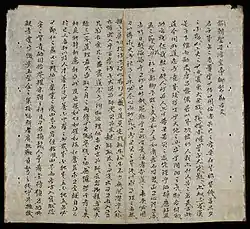

In 1483 Lê Thánh Tông created a new code for Đại Việt, called the Hồng Đức Code, which is Vietnam's National Treasures and is kept in the National Library in form of woodblocks No A.314.

The new laws were

"based on Chinese law but included distinctly Vietnamese features, such as recognition of the higher position of women in Vietnamese society than in Chinese society. Under the new code, parental consent was not required for marriage, and daughters were granted equal inheritance rights with sons. U.S. Library of Congress Country Studies – Vietnam

Economic policy

%252C_15th_century_-_Ewer_in_the_Shape_of_a_Dragon_-_1989.359_-_Cleveland_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

During the reign of Thánh Tông, Vietnamese export porcelains from Hải Dương kilns were found as far as West Asia.[13] Trowulan, capital of Majapahit, has yielded numerous Vietnamese ceramic products of the fifteenth century.[13]

Education policy

Thánh Tông encouraged the spread of Confucian values throughout the kingdom by having temples of literature built in all the provinces. There, Confucius was venerated and classic works on Confucianism could be found. He also halted the building of any new Buddhist or Taoist temples and ordered that monks were not to be allowed to purchase any new land.[14]

During his reign, Vietnamese Confucian scholarship had reached its golden era, with over 501 tiến sĩ (royal scholars) graduated,[8] out of the total 2,896 tiến sĩ graduated from 1076 to 1911.[10]

Ming China

During the reign of Thánh Tông, two related events put the Ming tributary system to the test. The first was the final destruction of Champa in 1471, and the other, the invasion of Laos between 1479 and 1481. After destroying Champa in 1471, the Vietnamese informed the Ming court that the fall of Champa's ruling house had come about as "a result of civil war."[15] In 1472, as Vietnamese pirates attacked Chinese and merchant ships in Hainan and the coast of Guangzhou, the Ming emperor called on Thánh Tông to end such activities. The court of Đại Việt denied its people would do such things.[16]

Champa

.png.webp)

In 1470, a Cham army numbered 100,000 under king Maha Sajan arrived and besieged the Vietnamese garrison at Huế. The local commander sent appeals to Hanoi for help.[17] Champa was defeated and the balance of power between the Cham and the Vietnamese for more than 500 years came to an end. The Ming annals recorded that in 1485 that "Champa is a distant and dangerous place, and Annam is still employing troops there."[18]

Laos and Burma

.gif)

Back in 1448, the Vietnamese had annexed the land of Muang Phuan in what is today the Plain of Jars in northeastern Laos, and Thánh Tông made that territory a prefecture of Đại Việt in 1471.[18] Began in 1478, Thánh Tông felt it was the time to take his revenge on King Chakkaphat of Laos, he collected his army along the Annamite border in preparation for an invasion.[19] Around the same time a white elephant had been captured and brought to King Chakkaphat. The elephant being a potent symbol of kingship was common throughout Southeast Asia, and Thánh Tông requested the animal's hair to be brought as a gift to the Đại Việt court. The request was seen as an affront, and according to legend a box filled with dung was sent instead.[19] Thánh Tông also realized that Laos was expanding its authority over Tai peoples who had previously acknowledged Vietnamese suzerainty and had regularly paid tribute to Đại Việt. Thus, the campaigns to reassert Dai Viet's authority over the Tai tribes led to the invasion of Laos.[20]

In fall 1479, Thánh Tông led an army of 180,000 men marched westward, attacked Muang Phuan, Lan Xang and Nan.[21] Luang Phabang was captured and the Laotian ruler Chakkaphat was killed. His forces pushed further to the upper Irrawaddy River, around Kengtung in modern-day Myanmar.[21] In 1482 Momeik borrowed troops of Dai Viet to invade Hsenwi and Lan Na.[21] By November 1484, his forces had withdrawn back to Dai Viet.[18][22] According to the Ming Shilu, in 1488 Burmese Ava embassy in China complained about Dai Viet’s incursion into its territory. In the next year (1489) the Ming court sent envoys to admonish Dai Viet to stop.[21]

Other regional powers and pirates

According to the Ming Shilu, Thánh Tông led ninety thousand troops to invade Lan Xang but was chased by the troops of the Malacca Sultanate, who killed thirty thousand Vietnamese soldiers.[23] In 1485, envoys of Champa, Lan Xang, Melaka, Ayutthaya, and Java arrived Dai Viet.[24] Also in 1475, pirates from Ryukyu Islands and Champa raided the port of Qui Nhơn.[25]

As a poet

A group of 28 poets was formally recognized by the court (the Tao Dan) Lê Thánh Tông himself was a poet and some of his poem has survived. He wrote the following at the start of his campaign against the Champa:

One hundred thousand officers and men,

Start out on a distant journey.

Falling on the sails, the rainSoftens the sounds of the army.

Family

- Father: Lê Thái Tông

- Mother: Empress Quang Thuc Ngo Thi Ngoc Dao (光淑文皇后吳氏; 1421 - 1496)

- Consort(s) and their Respective Issue(s):

- Empress Huy Gia (Empress Truong Lac) Nguyễn Thị Hằng of Nguyen Clan (徽嘉皇后阮氏; 1441 - 1505)

- Crown Prince Le Tranh, so Emperor Lê Hiến Tông

- Empress Nhu Huy of Phung clan (柔徽皇后馮氏; 1444 - 1489)

- Prince Le Tan, father of Emperor Lê Tương Dực

- Imperial Consort Minh of Pham clan (明妃范氏; 1448 - 1498)

- Prince Le Tung

- Princess Loi Y Lê Oánh Ngọc (雷懿公主黎莹玉)

- Princess Lan Minh Lê Lan Khuê (兰明公主黎兰圭; 1470 - 14??)

- Imperial Consort Kinh of Nguyen clan (敬妃阮氏; 1444 - 1485)

- Princess Minh Kinh Lê Thụy Hoa (明敬公主黎瑞华)

- Consort Nguyen thi (貴妃阮氏)

- Prince Le Thoan

- Lady Nguyen (修容阮氏)

- Lady Nguyen (才人阮氏; 1444 - 1479)

- Prince Lê Tranh

Ancestry

| Ancestry of King Lê Thánh Tông | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lê Thánh Tông. |

References

Citations

- Whitmore 2016, p. 200.

- Taylor 2013, p. 205.

- Taylor 2013, p. 204.

- Baldanza 2016, p. 84.

- Taylor 2013, p. 213.

- SarDesai 1988, p. 35-37.

- Bridgman 1840, p. 210.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 205.

- Li 2018, p. 169.

- Taylor 2013, p. 206.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 212.

- Li 2018, p. 171.

- Miksic & Yian 2016, p. 525.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 208.

- Wang 1998, p. 327-328.

- Whitmore 2011, p. 109.

- Sun 2006, p. 100.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 211.

- Simms (2013), p. 51–52.

- Wang 1998, p. 328.

- Sun 2006, p. 102.

- Sun 2006, p. 103.

- Sun 2006, p. 104.

- Whitmore 2011, p. 110.

- Whitmore 2011, p. 111.

Sources

- The first part of this history is based on the doctoral thesis of John K. Whitmore "The Development of the Le Government in Fifteenth Century Vietnam" (Cornell University, 1968). The thesis is mostly concerned with the structure and make-up of the Le government from 1427 to 1471.

- The second part is based in part on the Library of Congress Country studies for Vietnam

- Whitmore, John Kramer (2011), "Vân Đồn, the "Mạc Gap" and the End of Jiaozhi Ocean system: Trade and state of Đại Việt, Circa 1450-1550", in Li, Tana; Anderson, James A.; Cooke, Nola (eds.), The Tongking Gulf Through History, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 101–116

- Lary, Diana (2007). Diana Lary (ed.). The Chinese State at the Borders (illustrated ed.). UBC Press. ISBN 978-0774813334.

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (1996). The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. SUNY Presss. ISBN 0-791-42687-4.

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-05379-6.

- SarDesai, D. R. (1988). Vietnam, Trials and Tribulations of a Nation. Long Beach Publications.

- Taylor, K. W. (1999), "The early kingdoms", in Tarling, Nicholas (ed.), The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 1, From Early Times to c.1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Coedès, George (2015), The Making of South East Asia (RLE Modern East and South East Asia), Taylor & Francis

- Maspero, Georges (2002). The Champa Kingdom. White Lotus Co., Ltd. ISBN 978-9-747-53499-3.

- Li, Tana (2018). Nguyen Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Cornell University Press.

- Wang, Gungwu (1998), "Ming foreign relations: Southeast Asia", in Twitchett, Denis Crispin; Fairbank, John K. (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 301–332, ISBN 0-521-24333-5

- Whitmore, John K. (1970). Vietnamese Adaptations of Chinese Government Structure in the Fifteeth Century. Southeast Asia Studies, Yale University.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press.

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege 1200–1500, The Boydell Press

- Hall, Kenneth (1999), "Economic History of Early Southeast Asia", in Tarling, Nicholas (ed.), The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 1, From Early Times to c.1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of the Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- Yi, Insun (2006), "Lê Văn Hưu and Ngô Sĩ Liên: A Comparison of Their Perception of Vietnamese History", in Reid, Anthony; Tran, Nhung Tuyet (eds.), Viet Nam: Borderless Histories, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 45–71

- Sun, Laichen (2006), "Chinese Gunpowder Technology and Đại Việt, ca. 1390–1497", in Reid, Anthony; Tran, Nhung Tuyet (eds.), Viet Nam: Borderless Histories, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 72–120, ISBN 978-1-316-44504-4

- Whitmore, John K. (2016), "The Emergence of the state of Vietnam", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 9, The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Part 2, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 197–233

- Loke, Alexander; Chen-Wishart, Mindy; Vogenauer, Stefan, eds. (2018). Formation and Third Party Beneficiaries. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-192-53564-1.

- Taylor, K.W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87586-8.

- Buttinger, Joseph (1967). Vietnam: a Dragon Embattled: Vietnam at war. Praeger.

- Woodside, Alexander (2009). Lost Modernities: China, Vietnam, Korea, and the Hazards of World History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-67404-534-3.

- Simms, Sanda (2013). The Kingdoms of Laos: Six Hundred Years of History. Taylor & Francis.

- Hall, Kenneth R. (2011). A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100–1500. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-742-56762-7.

- Bridgman, Elijah Coleman (1840). Chronology of Tonkinese Kings. Harvard University. p. 205–212. ISBN 978-1-377-64408-0.

- Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Goh Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-73554-4.

- Wade, Geoff (2005), Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: an open access resource, Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press, National University of Singapore, retrieved 6 November 2012

| Preceded by Lê Nghi Dân |

Emperor of Đại Việt (ruled from 1460 to 1497) 1442–1497 |

Succeeded by Lê Hiến Tông |