Stonewall National Monument

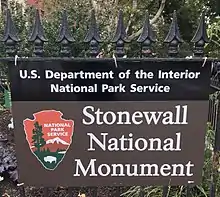

Stonewall National Monument is a 7.7-acre (3.1 ha) U.S. National Monument in the West Village neighborhood of Greenwich Village in Lower Manhattan, New York City.[2] The designated area includes the 0.19-acre (0.077 ha) Christopher Park and the block of Christopher Street bordering the park, which is directly across the street from the Stonewall Inn—the site of the Stonewall riots of June 28, 1969, widely regarded as the start of the modern LGBT rights movement in the United States.

| Stonewall National Monument | |

|---|---|

Stonewall Inn the day after President Obama's dedication on June 24, 2016 | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Location | West Village, Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°44′1.939″N 74°0′7.83″W |

| Area | 7.7 acres (3.1 ha) near the intersection of Christopher Street and 7th Avenue South |

| Built |

|

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Stonewall National Monument |

| Designated | June 28, 1999[lower-alpha 1] |

| Designated | February 16, 2000[1][lower-alpha 1] |

| Designated | June 24, 2016 |

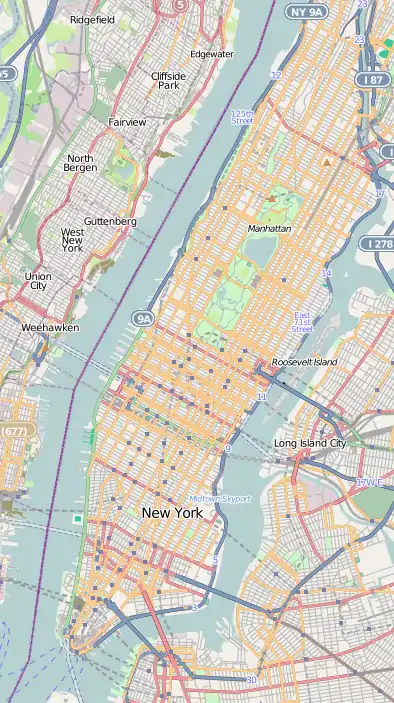

Location of Stonewall National Monument in Manhattan  Stonewall National Monument (New York City)  Stonewall National Monument (New York)  Stonewall National Monument (the United States) | |

Stonewall National Monument is the first U.S. National Monument dedicated to LGBT rights and history. It received its National Monument designation on June 24, 2016.

Early history

Stonewall National Monument encompasses the 0.19-acre (0.077 ha)[3][4] Christopher Park (also known as Christopher Street Park), a park originally built on a lot that New Netherland Director-General Wouter van Twiller settled as a tobacco farm from 1633 to 1638, when he died. The land was subsequently split up into 3 different farms. Trinity Church's and Elbert Herring's farms were located in the southern part of van Twiller's former farm, and Sir Peter Warren’s farm was located in the northern portion.[5]

Because of the unusual street grid that already existed in much of Greenwich Village, the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 would not quite fit into the pre-existing street grid. This resulted in several blocks with oblique angles, as well as many triangular street blocks. The former farms of Christopher Street were split into small lots from 1789 to 1829.[5][6]:37 After a subsequent large population increase in the early 19th century, the buildings on Christopher Street were dense with people.[5][6]:37

In 1835, the Great Fire of New York spread through the area and destroyed many city blocks. The little triangle of land bounded by Christopher, Grove, and 4th Streets, which was burned down, was condemned and turned into a park.[5][6]:37 The new Christopher Street Park, designed by architects Calvert Vaux and Samuel Parsons, Jr.,[7] was opened in 1837.[5][6]:37 The Stonewall Inn, which then consisted simply of two adjacent stables, opened across Christopher Street in 1843.[6]:35

The widening of 7th Avenue South, and the construction of the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line of the New York City Subway, effectively split the neighborhood into two pieces, separated by the now-widened avenue. By the 1940s, the area had deteriorated somewhat as people moved away.[5][6] During the 1950s, the social demographics changed as "Beat poets" moved into Greenwich Village.[8]:68–69 Meanwhile, the Stonewall Inn had changed uses; many different restaurants would be housed in the inn from the 1930s through 1966.[6]:35

Role in riots and aftermath

In 1966, the Stonewall Inn Restaurant—which had been located within the inn since the 1950s—closed for renovations due to a fire that devastated the space. The restaurant re-opened as a tavern on March 18, 1967,[9] under ownership of the Genovese crime family of the Mafia.[10]:183 The tavern was breaking rules on the sale of liquor, as it had no liquor license, but one officer of the New York City Police Department (NYPD) was reportedly accepting once-monthly bribes in exchange for allowing the tavern to go unlicensed.[6]:35[10]:185[11]:68

On June 27, 1969, the NYPD conducted a raid on the inn, now operating as a gay bar, because the inn did not have a liquor license. Riots started in the ensuing days, where thousands of rioters protested against the NYPD's raid.[5][6]:35–36 The riots solidified the Stonewall Inn's status as a gay icon.[5] The park also played a significant role in the riots—people had gathered at the park the morning after the first day of rioting, discussing the events of the previous day.[11]:180

Later years

The park itself was in dire need of renovation, so in the 1970s, the Friends of Christopher Park, which consisted entirely of volunteers mainly from the surrounding community, was created in order to oversee the park's upkeep. In 1983, NYC Parks embarked on a three-year, $130,000 project (equivalent to $333,709 in 2019[lower-alpha 2]) to rebuild the park to its original condition. Architect Philip Winslow planted new greenery and replaced the park's benches, walkways, light fixtures, and gates.[5]

In 1992, the Gay Liberation statue by George Segal was placed in Christopher Park, mirroring a near-identical statue at Stanford University.[5][12] The statue consists of four white figures (two standing men and two seated women) positioned in "natural, easy" poses.[9] Non-LGBT-related monuments in the park include two 1936 works that commemorated American Civil War fighters: a pole that honors the Fire Zouaves, as well as a statue made of bronze that honors Union general Philip Sheridan.[5][12] The park is surrounded by a fence that dates back to at least the late 19th century.[5][12]

Meanwhile, across the street, the Stonewall Inn had changed hands many times from 1969 to the 1990s, finally resuming the role of a gay bar by the 1990s.[6]:36

Landmark statuses

In 1999, David Carter, Andrew Dolkart, Gale Harris, and Jay Shockley researched and wrote the NRHP report for Stonewall, which was officially sponsored by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. When the listing was designated on June 29, 1999, it included the Stonewall Inn building, Christopher Park, and nearby streets.[13] It became the nation's first NRHP listing, out of more than 70,000 listings at the time, dedicated exclusively to LGBT accomplishments.[14] That same area was declared a National Historic Landmark on February 16, 2000.[1][15][16]

On June 23, 2015, the Stonewall Inn became a New York City Landmark,[17][18][19] making it the first city landmark to commemorate an LGBT icon.[20] The designation prompted Greenwich Village residents to lobby for the inn and the adjacent park to be labeled a National Monument.[21] Some members of Manhattan Community Board 2 wrote a letter to the National Park Service (NPS), which administers National Monuments, to request such a status for the Stonewall site.[21] The GVSHP also supported a National Monument designation for the site.[4] In 2016, The Trust for Public Land helped New York City prepare the property for transfer.[22] The Trust for Public Land worked with the NPS and NYC Parks to preserve the Stonewall Inn and recast Christopher Park as the Stonewall National Monument.[23]

On June 24, 2016, President Barack Obama officially designated the Stonewall National Monument,[24] making it the United States' first National Monument designated for an LGBT historic site.[25] The dedication ceremony was attended by New York City mayor Bill de Blasio; Senator Kirsten Gillibrand; Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell; and the Stonewall Inn's owners.[26] Some attendees saw the dedication as important because the Orlando, Florida, nightclub shooting, which had occurred two weeks prior to the dedication, had claimed the lives of 49 people, many of them gay Latino Americans.[27] The National Monument status encompasses a 7.7-acre (3.1 ha) area[26] that includes the Stonewall Inn, Christopher Street Park, and the block of Christopher Street bordering the park.[28][29] The National Park Foundation formed a new nonprofit organization to raise $2 million[30] in funds for a ranger station, visitor center, community activities, and interpretive exhibits for the monument.[30][31] In October 2017, a rainbow LGBT flag was raised on the monument, making it the first officially maintained LGBT flag at a federal monument.[32]

See also

- Gay Liberation Monument

- Homomonument

- LGBTQ culture in New York City

- List of National Monuments of the United States

- Pink Dolphin Monument

- Pink Triangle Park

- Transgender Memorial Garden

Notes

- The National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmark designations apply to roughly the same area that encompasses the National Monument, even though these designations preceded the National Monument designation by 17 and 16 years, respectively.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

References

- National Historic Landmarks Program (2008). "Stonewall". National Park Service. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- Tau, Byron (June 24, 2016). "Obama Designates Stonewall National Monument to LGBT Rights". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- "Christopher Park : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- Morowitz, Matthew (October 20, 2015). "Making Christopher Park a National Park". Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Christopher Park Highlights : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- Alfred Pommer; Eleanor Winters (2011). Exploring the Original West Village. The History Press. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-1-60949-151-2.

- "Christopher Park". The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- Adam, Barry (1987). The Rise of a Gay and Lesbian Movement, G. K. Hall & Co. ISBN 0-8057-9714-9

- "Christopher Park Monuments: Gay Liberation". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- Duberman, Martin (1993). Stonewall, Penguin Books. ISBN 0-525-93602-5

- Carter, David (2004). Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution, St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-34269-1

- "Christopher Park: Bringing the Community Together". The Village Alliance. May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "National Register of Historic Places Report" (PDF). Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- Dunlap, David W. (June 26, 1999). "Stonewall, Gay Bar That Made History, Is Made a Landmark". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- David Carter; Andrew Scott Dolkart; Gale Harris & Jay Shockley (May 27, 1999). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Stonewall (Text)". National Park Service. Retrieved June 24, 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - David Carter; Andrew Scott Dolkart; Gale Harris & Jay Shockley (May 27, 1999). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Stonewall (Photos)". National Park Service. Retrieved June 24, 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Curbed (June 23, 2015). "Rejoice, Stonewall Inn Is Officially a New York City Landmark". Curbed NY. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- Brazee, Christopher D. et al. (June 23, 2015) Stonewall Inn Designation Report New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

- "New York City Makes Stonewall Inn a Landmark". The New York Times. June 24, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Tcholakian, Danielle (June 23, 2015). "Stonewall Inn Is Officially a NYC Landmark in 'Unprecedented Move'". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- Rosenberg, Zoe (July 28, 2015). "NYers Want Christopher Park To Be a National Monument". Curbed NY. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- "At Stonewall, a new national monument to the struggle for LGBT rights". The Trust for Public Land. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- Benepe, Adrian (August 18, 2017). "Whose Parks, Which History? Why Monuments Have Become a National Flashpoint". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- "President Obama Designates Stonewall National Monument" (official announcement from White House Press Office; June 24, 2016)

- Orangias, Joe Joe; Simms, Jeannie; French, Sloane (August 4, 2017). "The Cultural Functions and Social Potential of Queer Monuments: A Preliminary Inventory and Analysis". Journal of Homosexuality. 65 (6): 705–726. doi:10.1080/00918369.2017.1364106. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 28777713.

- Begley, Sarah. "Officials Celebrate Stonewall Inn's Dedication as National Monument". TIME.com. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Stonewall Inn Dedicated as National Monument to Gay Rights". ABC News. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- Mallin, Alexander (June 24, 2016). "Obama Designates Stonewall as First National Monument for LGBT Rights". ABC News. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- Karch, Lauren (June 30, 2016). "National Park Foundation Plans to Raise $2 Million for new Stonewall National Monument – Non Profit News For Nonprofit Organizations". Non Profit News For Nonprofit Organizations | Nonprofit Quarterly. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- Nakamura, David; Eilperin, Juliet (June 24, 2016). "With Stonewall, Obama designates first national monument to gay rights movement". Washington Post. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- Ziv, Stav (October 5, 2017). "For the first time ever, an LGBT pride flag will fly on federal land at the Stonewall monument". Newsweek. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stonewall National Monument. |

- "President Obama Designates Stonewall National Monument" (official announcement from White House Press Office)

- Announcing the Stonewall National Monument on YouTube

- Official website at the National Park Service

- Stonewall Forever a Monument to 50 Years of Pride Stonewall Forever Monument