Metro Transit (Minnesota)

Metro Transit is the primary public transportation operator in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul area of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the largest operator in the state. The system is a division of the Metropolitan Council, the region's metropolitan planning organization (MPO), averaging 264,347 riders each weekday, carrying 90% to 95% of the transit riders in the region on a combined network of regular-route buses, light rail and commuter rail.[4] The remainder of Twin Cities transit ridership is generally split among suburban “opt-out” carriers operating out of cities that have chosen not to participate in the Metro Transit network. The biggest opt-out providers are Minnesota Valley Transit Authority (MVTA), Maple Grove Transit and Southwest Transit (SW Transit). The University of Minnesota also operates a campus shuttle system that coordinates routes with Metro Transit services.

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Owner | Metropolitan Council |

| Locale | Minneapolis – Saint Paul |

| Transit type | Transit bus Bus rapid transit Light rail Commuter rail Paratransit |

| Number of lines | 125 routes[1]

|

| Number of stations | 37 light rail 40 bus rapid transit 7 commuter rail |

| Daily ridership | 251,564 (2019)[1] |

| Annual ridership | 77.9 million (2019)[1] |

| Chief executive | Wes Kooistra |

| Headquarters | Fred T. Heywood Office Building and Garage 560 North Sixth Avenue Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States |

| Website | http://www.metrotransit.org/ |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | May 20, 1967 (established)[2] September 18, 1970 (bus operations)[3] June 26, 2004 (light rail) November 16, 2009 (commuter rail) June 11, 2016 (bus rapid transit) |

| Number of vehicles | 904 buses[1]

115 rail vehicles

|

In 2017, buses carried about 68% of the system's passengers. Just above 16% of ridership was concentrated on Metro Transit's busiest route, the Green Line light rail. The region's other light rail line, the Blue Line, fell close behind, carrying 13% of Metro Transit passengers. Nearly 2% rode the A Line arterial rapid bus line. The remaining approximately 1% rode the Northstar Commuter Rail service.[5] In 2015, Metro Transit saw its highest yearly ridership ever, with a total of 85.8 million trips, 62.1 million (72%) of which were on buses. The remaining 23.7 million (28%) of passengers traveled on the region's rail lines, including the recently opened Green Line.[6] The single-day ridership record is 369,626, set on September 1, 2016.[7]

Metro Transit drivers and vehicle maintenance personnel are organized through the Amalgamated Transit Union. The agency also contracts with private providers such as First Transit to offer paratansit services which operate under the Metro Mobility brand.

History

The agency was established by the Minnesota State Legislature in 1967 as the Metropolitan Transit Commission (MTC).[8] MTC's operations were moved under the auspices of the Metropolitan Council in 1994, prompting a name change to “Metropolitan Council Transit Operations” and then, in 1998, to Metro Transit. The organization traces its history back to the 19th-century streetcar systems of the region through the acquisition in 1970 of the Twin City Lines bus system from businessman Carl Pohlad. At the time of the acquisition, Twin City Lines had 635 buses: 75% of those were over 15 years old and 86 buses were so old that they were banned from operating in Minneapolis. MTC acquired 465 new buses over the next five years and built many new bus shelters.[9]

Shortly thereafter, a long battle began to return rail transit to the region and efforts for additional lines continue at a snail's pace. It took 32 years to see the first line implemented. In 1972, the Regional Fixed Guideway Study for MTC proposed a $1.3 billion 37- or 57-mile (sources differ) heavy-rail rapid transit system, but the then-separate Metropolitan Council disagreed with that idea—refusing to even look at the plan—and continuing political battles prevented its implementation. The Met Council had its own plans for bus rapid transit in the Cities. Another system using smaller people movers was proposed in the 1975 Small Vehicle Fixed Guideway Study and gained the most traction with the Saint Paul city council, but was eventually dropped in 1980. In the 1980s, light rail was proposed as an alternative and several possible corridors were identified, including the Central Corridor, for which a draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) was drawn up in 1982.[9][10][11] However, it was another two decades before the Blue Line light rail line began operation on June 26, 2004, by then, just over 50 years since the last regular-service streetcar ran on June 19, 1954, under the old Twin City Lines. Heavy-rail commuter service began on November 14, 2009, with the Northstar Line.

Metro Transit does not cover the whole Twin Cities area. Bus service in the suburbs was being cut back in the early 1980s and suburb-to-suburb service was limited (an issue that remains today). In 1986, cities and counties in the seven-county metropolitan area were given the option to run their own bus services and leave the MTC system. About 17.5% of the area which has regular route transit service is served by these six other “opt out” transit systems. About 5% of the system is contracted to private transit providers.

In the mid-2000s decade, the system claimed to have a safety record five times better than the national average.

Funding

Metro Transit currently receives the majority of its funding from the State Motor Vehicle Sales Tax, the State General Fund, fares and federal revenues. Metro Transit prepares an annual calendar budget, but most of its subsidy comes from state funds, on a July 1 biennial budget. Between 2001 and 2006, reductions in state general funds and state motor vehicle sales tax collections forced a set of service cuts, fare increases and fuel surcharges, all of which reduced ridership.

Local policy requires that one third of the system's funding is to come from fares and current operations slightly exceed that level. Since 1 October 2008, fares on all buses and trains increased by 25 cents.[12] Express routes cost more (on limited-stop portions) and certain eligible individuals (such as riders with disabilities) may ride for $1. Many of the fares are more expensive during rush hour periods. For instance, a rush-hour ride on an express bus costs $3.25, as opposed to $2.50 for non-rush hours. [13]

The system does not make much use of fare zones aside from downtown zones in Minneapolis and St. Paul, where rides only cost $0.50. Fare transfer cards valid for 2.5 hours are available upon payment of fare. Only the Northstar commuter rail line charges fares based on distance. A number of discounted multiple-use transit pass options are available. In early 2007, the system introduced a contactless smart card (the Go-To card) for paying fares.

A second fare increase occurred in 2017. "Under the new system, local fares for off-peak hours will increase from $1.75 to $2; while rides will go from $2.25 to $2.50 for peak hours. Metro Mobility users will pay $3.50 to $4.50 per ride, as well as an additional 75-cent surcharge for trips greater than 15 miles. Transit Link Dial-A-Ride fares will increase, on average, by $1.60, and include a 75-cent distance surcharge."[14]

METRO System

Metro is the system of frequent, all-day light rail and bus rapid transit lines owned by the Metropolitan Council that provide station-to-station service to the Twin Cities region. Metro Transit is the operator of both of the region's light rail lines, the Metro Blue Line and the Metro Green Line, and two of the region's bus rapid transit lines, the Metro A Line, Metro C Line and the Metro Red Line. An additional bus rapid transit line, the Metro Orange Line, and an extension of the Metro Green Line are currently under construction.

Metro Blue Line

The METRO Blue Line opened on June 26, 2004 as the state's first light rail line, providing service between Hennepin Ave./Warehouse District Station and Fort Snelling Station. On December 4, 2004, service was extended to Mall of America station via Minneapolis–St. Paul International Airport. As part of the Northstar Commuter Rail project, on November 14, 2009, the Blue Line was extended a few blocks north to Target Field (Metro Transit Station) to provide connections to the new commuter rail line. Current plans call for a northern extension of the Metro Blue Line to Brooklyn Park, the current opening date is in the air as BNSF is unwilling to work with Metro Transit on co-locating freight rail and light rail.

Metro Green Line

The METRO Green Line opened on June 14, 2014 and connects Downtown Minneapolis, the University of Minnesota, the Midway and Saint Anthony Park neighborhoods of St. Paul, the State Capitol and Downtown St. Paul with light rail service. Southwest LRT is a currently under construction extension of the Green Line through the southwest suburbs to Eden Prairie. The extension expected to begin operations in 2023. On January 14, 2021 the Metropolitan Council announced that the Southwest LRT would not be able to make its targeted opening year of 2023 due to poor soil conditions in the Kenilworth Corridor.[15]

Metro Red Line

The METRO Red Line is a bus rapid transit line was operated by Minnesota Valley Transit Authority on behalf of the Metropolitan Council until December 4th, 2020 when Metro Transit assumed all operations the Red Line provides connections between the Blue Line at Mall of America and the southern suburb of Apple Valley. Service began on June 22, 2013.

Metro Orange Line

The METRO Orange Line is an under construction bus rapid transit line that will operate along Interstate 35W from Downtown Minneapolis to the southern suburbs, terminating in Burnsville. The line is expected to begin operations in 2021.

Metro A Line

The METRO A Line, is a bus rapid transit line, that operates along Snelling Avenue and Ford Parkway. The A Line connects the Metro Blue Line at 46th Street Station to the Rosedale Transit Center with a connection at the METRO Green Line Snelling Avenue station. The A Line is the first in a series of planned bus rapid transit lines that replace high ridership local routes. Service began on June 11, 2016.[16]

Metro C Line

The METRO C Line is a bus rapid transit line that operates along Penn Avenue and Olson Memorial Highway. The C Line connects Brooklyn Center, North Minneapolis, and Downtown Minneapolis. Service began on June 8, 2019.[17][18][19]

Transitway projects in development

Metro Gold Line

The METRO Gold Line is a bus rapid transit line currently under development. The route will run from Downtown Saint Paul to the east suburbs, terminating in Woodbury. It would be the first bus rapid transit line in the state to have dedicated lanes. Operations are anticipated to start in 2024.

Metro D Line

The METRO D Line is a bus rapid transit route which will start construction in Spring 2021. The route will run from Brooklyn Center through North Minneapolis, Downtown Minneapolis, and South Minneapolis to the Mall of America. The new line will replace Route 5, which is currently the highest ridership bus route in the state, carrying 18,500 passengers daily. The route will travel mostly along Fremont Avenue and Chicago Avenue and will share some stations with the METRO C Line.[20] Metro Transit anticipates the line will be operational by 2022.

Metro B Line

The METRO B Line is a bus rapid transit route proposed for Lake Street, running from Bde Maka Ska in Minneapolis's Uptown neighborhood to the Snelling & Dayton station of the A Line and continuing to Downtown Saint Paul along Selby Avenue.[21][22] Planning is underway and will continue through early 2020. Station design is planned for 2020–2021 with beginning of construction anticipated in 2022, pending full funding.

Metro E Line

The METRO E Line is a bus rapid transit route proposed for Hennepin Avenue.[23] The route will run from the University of Minnesota through Downtown Minneapolis, Uptown Minneapolis, and Southwest Minneapolis to Southdale Center. Planning is underway to determine specific station locations.

Other corridors

In fall 2020 Metro Transit announced that they would be resuming community engagement and development of upgrading local routes to bus rapid transit lines as part of Network Next. Out of 11 corridors, three would be selected as to be upgraded after completion of the Metro E Line.[24][25] All three lines would be constructed at once around 2024-2025 and would be part of the METRO network.[26]

- METRO F Line

- METRO G Line

- METRO H Line

Additionally, two transitway projects that would likely be added to the METRO system are under development but not currently being planned directly by Metro Transit.

Bus routes

Metro Transit operates 123 bus routes, 66 of which are local routes and 51 are express routes. An additional six bus routes are operated under contract with Maple Grove Transit. In 2012, Metro Transit buses averaged 230,575 riders per weekday. The system operates almost 900 wait shelters, including 180 reclaimed from CBS Outdoor in March 2014.[27]

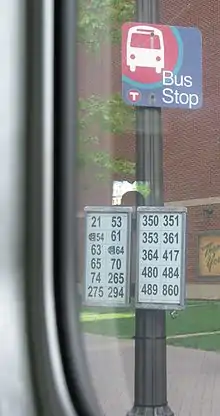

Bus routes are numbered in accordance to portions of the metropolitan area served. Bus routes that primarily serve Minneapolis are numbered 1–49, 50–59 are inner-city limited-stop routes, 60–89 primarily serve St. Paul, and route 94 is an express route that connects the core areas of Minneapolis and St. Paul via I-94. 100 series routes are primarily commuter routes connecting outlying neighborhoods of Minneapolis and St. Paul to the cities' cores, as well as the University of Minnesota. 200 series routes serve the northeast metro, 300 series the southeast, 400 series the southern Dakota and Scott County suburbs, 500 series the suburbs of Richfield, Edina, and Bloomington, 600 series the west and southwest metro, 700 series the northwest metro and 800 series northern Anoka County suburbs.

Three-digit route numbers are further subdivided into two groups. Routes ending in x00–x49 are typically local service bus routes connecting METRO stations, shopping areas and other local destinations, whereas those ending in x50–x99 are primarily express service routes which connect outlying suburbs and park and ride facilities to the central business districts of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Additionally, the Northstar Commuter Rail line is publicly given route number 888.

High Frequency Network

A subset of the bus network, known as the High Frequency Network was created on September 9, 2006. This network highlights fourteen bus routes that offer service every 15 minutes or better on weekday periods from 6 am to 7 pm and on Saturdays from 9 am to 6 pm. Segments of routes 2, 5, 6, 10, 11, 18, 21, 64, 54, 515, and all of METRO A Line, C Line, Blue Line, and Green Line are currently part of the High Frequency Network.[28]

Northstar Line

The Northstar Line is a commuter rail line providing service between Minneapolis and Big Lake, Minnesota, which opened on November 16, 2009. There are additional bus connections to Becker and St. Cloud, with five round-trips in the peak direction, one reverse commute round-trip on weekdays, and three round-trips on Saturdays and Sundays. Additional service is provided on event days, such as during Twins and Vikings games or the Super Bowl. However, service is not provided on holidays.

Facilities

Dedicated downtown transit streets

Nicollet Mall had been used exclusively for buses and taxis for many years, but the number of buses is being reduced to allow more bicycle use of Nicollet. Beginning in 2005, Metro Transit and the city of Minneapolis experimented with diverting buses from Nicollet to Hennepin Avenue in the evening hours to reduce noise. In December 2009, the “MARQ2” project, partly funded by the federal government under the Urban Partnership Agreement, was completed, in which two-lane busways were built along the parallel roads of Marquette and 2nd Avenue South.[29] A system of lettered gates was established, by which buses would only stop every other block along those two one-mile corridors. NexTrip digital signs with arrival times were also added, although they weren't functioning at the beginning of the rollout. NexTrip information has also been available through the Metro Transit website since 2008 and can be accessed with mobile web browsers.[30]

Bus-only shoulders

Since 1991, Metro Transit buses have been allowed to use “bus-only shoulders,” road shoulders to bypass traffic jams. Currently, buses are allowed to travel no more than 35 mph (56 km/h) or 15 mph (24 km/h) faster than the congested traffic in the general purpose lanes. Bus drivers must be very attentive when taking the bus onto the shoulder, since that part of the road is only about one foot wider than the buses in many cases. To help with this issue, researchers at the University of Minnesota helped rig up a bus with a lane-keep system, along with a heads-up display connected to a radar system to alert the driver of any obstacles. The technology was an adaptation of a system previously tested with drivers of snowplows and made some headlines in the early 2000s. This system will be more widely deployed under the Urban Partnership Agreement that assisted in the Marq2 project.[31]

Transit centers

Metro Transit operates service to 28 transit centers, which provide connection points for bus and rail service throughout the metropolitan area.

Park and rides

Metro Transit operates service to 79 park and ride lots and ramps, with a total of 13,829 parking spaces. These lots allow commuters to park their cars for free and take buses and trains to the downtown areas to avoid traffic congestion and parking fees.

Better Bus Stops

A 2014 Star Tribune investigation revealed that 460 bus stops in Metro Transit's service area had enough riders to qualify for a shelter under the agency's standards but did not have one, while 200 of the 801 existing shelters did not have enough riders to justify a shelter.[32] Metro Transit committed to spending $5.8 million to improve shelters, with $3.26 million coming from a Federal Transit Administration "Ladders of Opportunity" grant.[33] To spend the money Metro Transit created a program called Better Bus Stops that reevaluated shelter placement guidelines. Metro Transit dedicated 10% of project funds on community outreach, which helped guide bus shelter and transit information changes at bus stops. Bus stop signs were redesigned to include more route information, and the agency made a goal of adding 150 additional shelters for a total of around 950.[34][35] New shelter placement guidelines did away with different threshold for suburban and urban stops, and made the criteria based just on number of boardings and proximity to priority locations.[36]

Fleet

Buses

Metro Transit operates the Gillig Phantom, Gillig Advantage (which comprises the majority of the fleet), New Flyer D60HF, D60LFR, Xcelsior XD60, and MCI D4500.

In the 2000s, most buses had a mostly white livery with a predominantly blue strip running horizontally along the side and a large white “T” inside a red circle on the roof. Diesel–electric hybrid buses introduced toward the end of the decade spurred new color schemes, with yellow at the front and the blue line moved above the side windows. The METRO light-rail vehicles have a different color scheme: predominantly blue and white, with yellow on each end. Metro Transit also uses vehicle wrap advertising on some buses and light rail cars, creating a different appearance.

All of the buses are handicapped-accessible, either using hydraulic lifts or a low-floor design. The Metropolitan Council also operates the Metro Mobility paratransit system for door-to-door transportation.

All Metro Transit buses and light- and heavy-rail trains have bike racks installed.[37]

Rail

Bombardier Flexity Swift 27 vehicles are operated on the Blue Line light rail line. There are also 59 Siemens S70 vehicles operating on both the Blue and Green Line light rail lines.[38][39] Rolling stock for the Northstar Line commuter rail line consists of Bombardier BiLevel Coaches pulled by MotivePower MP36 locomotives.

See also

Opt-out and regional providers:

References

- "Metro Transit 2019 Facts". Metro Transit. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Dornfeld, Steven (Fall 2019). "1969 Bus Strike" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "The OughtaBiography: 1970-1980" (PDF). Metropolitan Transit Commission. September 1980. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Metro Transit 2017 Facts". Metro Transit. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- "Rail lines set records as Metro Transit ridership tops 81.9 million in 2017 - Metro Transit". www.metrotransit.org. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- "2015 Metro Transit Facts" (PDF). Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- Harlow, Tim (September 9, 2016). "Vikings, Twins, traffic fears help Metro Transit shatter single-day ridership record". Star Tribune.

- Christopher, Mary Kay. Bus Transit Service in Land Development Planning. Transportation Research Board, 2006.

- "A bold experiment: the Metropolitan Council at 40" (PDF). Metropolitan Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2010. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- Jeff Severns Guntzel (May 19, 2008). "A train linking Minneapolis and St. Paul? We had that scoop in 1984". City Pages. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- "ALL ABOARD: For the Transit Study that Never Ends". City Pages. September 5, 1984.

- "Home - Metro Transit". www.metrotransit.org. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Fares - Metro Transit". Metro Transit. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Moore, Janet (July 27, 2017). "Met Council votes to increase transit fares by 25 cents". Star Tribune. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- https://metrocouncil.org/Transportation/Projects/Light-Rail-Projects/Southwest-LRT.aspx?source=child

- http://www.metrotransit.org/a-line-project A-Line

- "C Line Project - Metro Transit". www.metrotransit.org. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- "Construction officially begins on C-Line rapid bus". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- "C Line (Penn Avenue rapid bus)". Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "D Line (Chicago-Fremont rapid bus)". Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "METRO B Line (Lake Street / Marshall Avenue)". Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "St. Paul chamber, mayor call for new B Line bus to extend to downtown St. Paul". Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "E Line (Hennepin Avenue rapid bus project)". Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- Slatton, Shannon (17 September 2020). "Feedback Sought for Future Bus Rapid Transit line in Brooklyn Park". CCX Media. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "Planning resumes on future bus improvements". www.metrotransit.org. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "Network Next Project FAQs". www.metrotransit.org. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "As big cities privatize bus shelters, Minneapolis moves them to government control". Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-04.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "High Frequency network". www.metrotransit.org. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Faster express service is coming to downtown Minneapolis". Metro Transit. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- "Exactly when is my next bus departing?". Metropolitan Council. May 14, 2009. Archived from the original on May 16, 2010. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- "Minneapolis Urban Partnership Agreement". Urban Partnership Agreement and Congestion Reduction Demonstration Programs. U.S. Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 2010-08-27. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- Roper, Eric (September 2, 2014). "Hundreds of metro bus stops have thousands seeking shelters". Star Tribune. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Melo, Frederick (September 30, 2014). "For better bus shelters, Metro Transit commits $5.8 million". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Roper, Eric (January 16, 2020). "Metro Transit says bus stops are improved with better signs, more shelters". Star Tribune. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "Better Bus Stops". Metro Transit. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Higashide, Steven (2019). Better Buses Better Cities. Island Press. pp. 68–73. ISBN 978-1642830149.

- "Metro Transit - Bike Options".

- "Central Corridor Contracts Awarded". Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "FTA Signs Agreement to Fund Central Corridor". Retrieved 20 September 2011.