Weight training

Weight training is a common type of strength training for developing the strength and size of skeletal muscles.[2] It utilizes the force of gravity in the form of weighted bars, dumbbells or weight stacks in order to oppose the force generated by muscle through concentric or eccentric contraction. Weight training uses a variety of specialized equipment to target specific muscle groups and types of movement.

Sports in which weight training is used are : bodybuilding, weightlifting, powerlifting, strongman, highland games, hammer throw, shot put, discus throw, and javelin throw. Many other sports use strength training as part of their training regimen, notably: American football, baseball, basketball, canoeing, cricket, football, hockey, lacrosse, mixed martial arts, rowing, rugby league, rugby union, track and field, boxing and wrestling.

History

The genealogy of lifting can be traced back to the beginning of recorded history[3] where humanity's fascination with physical abilities can be found among numerous ancient writings. In many prehistoric tribes, they would have a big rock they would try to lift, and the first one to lift it would inscribe their name into the stone. Such rocks have been found in Greek and Scottish castles.[4] Progressive resistance training dates back at least to Ancient Greece, when legend has it that wrestler Milo of Croton trained by carrying a newborn calf on his back every day until it was fully grown. Another Greek, the physician Galen, described strength training exercises using the halteres (an early form of dumbbell) in the 2nd century.

Ancient Greek sculptures also depict lifting feats. The weights were generally stones, but later gave way to dumbbells. The dumbbell was joined by the barbell in the later half of the 19th century. Early barbells had hollow globes that could be filled with sand or lead shot, but by the end of the century these were replaced by the plate-loading barbell commonly used today.[5]

Another early device was the Indian club, which came from ancient India where it was called the "mugdar" or ''gada''. It subsequently became popular during the 19th century, and has recently made a comeback in the form of the clubbell.

Weightlifting was first introduced in the Olympics in the 1896 Athens Olympic games as a part of track and field, and was officially recognized as its own event in 1914.

The 1960s saw the gradual introduction of exercise machines into the still-rare strength training gyms of the time. Weight training became increasingly popular in the 1970s, following the release of the bodybuilding movie Pumping Iron, and the subsequent popularity of Arnold Schwarzenegger. Since the late 1990s increasing numbers of women have taken up weight training; currently nearly one in five U.S. women engage in weight training on a regular basis.[6]

Basic principles

The basic principles of weight training are essentially identical to those of strength training, and involve a manipulation of the number of repetitions (reps), sets, tempo, exercise types, and weight moved to cause desired increases in strength, endurance, and size. The specific combinations of reps, sets, exercises, and weights depends on the aims of the individual performing the exercise.

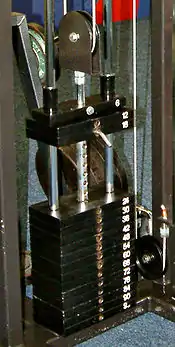

In addition to the basic principles of strength training, a further consideration added by weight training is the equipment used.[2] Types of equipment include barbells, dumbbells, kettlebells, pulleys and stacks in the form of weight machines, and the body's own weight in the case of chin-ups and push-ups. Different types of weights will give different types of resistance, and often the same absolute weight can have different relative weights depending on the type of equipment used. For example, lifting 10 kilograms using a dumbbell sometimes requires more force than moving 10 kilograms on a weight stack if certain pulley arrangements are used. In other cases, the weight stack may require more force than the equivalent dumbbell weight due to additional torque or resistance in the machine. Additionally, although they may display the same weight stack, different machines may be heavier or lighter depending on the number of pulleys and their arrangements.

Weight training also requires the use of proper or 'good form', performing the movements with the appropriate muscle group, and not transferring the weight to different body parts in order to move greater weight (called 'cheating'). Failure to use good form during a training set can result in injury or a failure to meet training goals. If the desired muscle group is not challenged sufficiently, the threshold of overload is never reached and the muscle does not gain in strength. At a particularly advanced level; however, "cheating" can be used to break through strength plateaus and encourage neurological and muscular adaptation.

Safety

Weight training is a safe form of exercise when the movements are controlled and carefully defined. However, as with any form of exercise, improper execution and the failure to take appropriate precautions can result in injury. If injured, full recovery is suggested before starting to weight train again or it will result in a bigger injury.

Maintaining proper form

Maintaining proper form is one of the many steps in order to perfectly perform a certain technique. Correct form in weight training improves strength, muscle tone, and maintaining a healthy weight. Proper form will prevent any strains or fractures.[8] When the exercise becomes difficult towards the end of a set, there is a temptation to cheat, i.e., to use poor form to recruit other muscle groups to assist the effort. Avoid heavy weight and keep the number of repetitions to a minimum. This may shift the effort to weaker muscles that cannot handle the weight. For example, the squat and the deadlift are used to exercise the largest muscles in the body—the leg and buttock muscles—so they require substantial weight. Beginners are tempted to round their back while performing these exercises. The relaxation of the spinal erectors which allows the lower back to round can cause shearing in the vertebrae of the lumbar spine, potentially damaging the spinal discs.

Stretching and warm-up

Weight trainers commonly spend 5 to 20 minutes warming up their muscles before starting a workout. It is common to stretch the entire body to increase overall flexibility; many people stretch just the area being worked that day. It has been observed that static stretching can increase the risk of injury due to its analgesic effect and cellular damage caused by it.[9] A proper warm-up routine, however, has shown to be effective in minimizing the chances of injury, especially if they are done with the same movements performed in the weigh lifting exercise.[10] When properly warmed up the lifter will have more strength and stamina since the blood has begun to flow to the muscle groups.[11]

Breathing

In weight training, as with most forms of exercise, there is a tendency for the breathing pattern to deepen. This helps to meet increased oxygen requirements. Holding the breath or breathing shallowly is avoided because it may lead to a lack of oxygen, passing out, or an increase in blood pressure. Generally, the recommended breathing technique is to inhale when lowering the weight (the eccentric portion) and exhale when lifting the weight (the concentric portion). However, the reverse, inhaling when lifting and exhaling when lowering, may also be recommended. Some researchers state that there is little difference between the two techniques in terms of their influence on heart rate and blood pressure.[12] It may also be recommended that a weight lifter simply breathes in a manner which feels appropriate.

Deep breathing may be specifically recommended for the lifting of heavy weights because it helps to generate intra-abdominal pressure which can help to strengthen the posture of the lifter, and especially their core.[13]

In particular situations, a coach may advise performing the valsalva maneuver during exercises which place a load on the spine. The vasalva maneuver consists of closing the windpipe and clenching the abdominal muscles as if exhaling, and is performed naturally and unconsciously by most people when applying great force. It serves to stiffen the abdomen and torso and assist the back muscles and spine in supporting the heavy weight. Although it briefly increases blood pressure, it is still recommended by weightlifting experts such as Rippetoe since the risk of a stroke by aneurysm is far lower than the risk of an orthopedic injury caused by inadequate rigidity of the torso.[14] Some medical experts warn that the mechanism of building "high levels of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP)...produced by breath holding using the Valsava maneuver", to "ensure spine stiffness and stability during these extraordinary demands", "should be considered only for extreme weight-lifting challenges — not for rehabilitation exercise".[15]

Hydration

As with other sports, weight trainers should avoid dehydration throughout the workout by drinking sufficient water. This is particularly true in hot environments, or for those older than 65.[16][17][18][19][20]

Some athletic trainers advise athletes to drink about 7 imperial fluid ounces (200 mL) every 15 minutes while exercising, and about 80 imperial fluid ounces (2.3 L) throughout the day.[21]

However, a much more accurate determination of how much fluid is necessary can be made by performing appropriate weight measurements before and after a typical exercise session, to determine how much fluid is lost during the workout. The greatest source of fluid loss during exercise is through perspiration, but as long as your fluid intake is roughly equivalent to your rate of perspiration, hydration levels will be maintained.[18]

Under most circumstances, sports drinks do not offer a physiological benefit over water during weight training.[22] However, high-intensity exercise for a continuous duration of at least one hour may require the replenishment of electrolytes which a sports drink may provide.[23][24] 'Sports drinks' that contain simple carbohydrates & water do not cause ill effects, but are most likely unnecessary for the average trainee.

Insufficient hydration may cause lethargy, soreness or muscle cramps.[25] The urine of well-hydrated persons should be nearly colorless, while an intense yellow color is normally a sign of insufficient hydration.[25]

Avoiding pain

An exercise should be halted if marked or sudden pain is felt, to prevent further injury. However, not all discomfort indicates injury. Weight training exercises are brief but very intense, and many people are unaccustomed to this level of effort. The expression "no pain, no gain" refers to working through the discomfort expected from such vigorous effort, rather than to willfully ignore extreme pain, which may indicate serious soft tissue injuries. The focus must be proper form, not the amount of weight lifted.[26]

Discomfort can arise from other factors. Individuals who perform large numbers of repetitions, sets, and exercises for each muscle group may experience a burning sensation in their muscles. These individuals may also experience a swelling sensation in their muscles from increased blood flow also known as edema (the "pump"). True muscle fatigue is experienced as loss of power in muscles due to a lack of ATP, the energy used by our body, or a marked and uncontrollable loss of strength in a muscle, arising from the nervous system (motor unit) rather than from the muscle fibers themselves.[27] Extreme neural fatigue can be experienced as temporary muscle failure. Some weight training programs, such as Metabolic Resistance Training, actively seek temporary muscle failure; evidence to support this type of training is mixed at best.[28] Irrespective of their program, however, most athletes engaged in high-intensity weight training will experience muscle failure during their regimens.

Beginners are advised to build up slowly to a weight training program. Untrained individuals may have some muscles that are comparatively stronger than others; nevertheless, an injury can result if (in a particular exercise) the primary muscle is stronger than its stabilizing muscles. Building up slowly allows muscles time to develop appropriate strengths relative to each other. This can also help to minimize delayed onset muscle soreness. A sudden start to an intense program can cause significant muscular soreness. Unexercised muscles contain cross-linkages that are torn during intense exercise. A regimen of flexibility exercises should be implemented before and after workouts. Since weight training puts great strain on the muscles, it is necessary to warm-up properly. Kinetic stretching before a workout and static stretching after are a key part of flexibility and injury prevention.

Other precautions

Anyone beginning an intensive physical training program is typically advised to consult a physician, because of possible undetected heart or other conditions for which such activity is contraindicated.

Exercises like the bench press or the squat in which a failed lift can potentially result in the lifter becoming trapped under the weight are normally performed inside a power rack or in the presence of one or more spotters, who can safely re-rack the barbell if the weight trainer is unable to do so. In addition to spotters, knowledge of proper form and the use of safety bars can go a long way to keep a lifter from suffering injury due to a failed repetition.

Equipment

Weight training usually requires different types of equipment, most commonly kettle bells, dumbbells, barbells, weight plates, and weight machines. Various combinations of specific exercises, machines, dumbbells, and barbells allow trainees to exercise body parts in numerous ways.

Other types of equipment include:

- Lifting straps, which allow more weight to be lifted by transferring the load to the wrists and avoiding limitations in forearm muscles and grip strength.

- Weightlifting belts, which are meant to brace the core through intra-abdominal pressure (and not directly assist the lower back muscles as commonly believed). Controversy exists regarding the safety of these devices[29] and their proper use is often misunderstood. Powerlifting belts, which are thick and have the same width all around, are designed for maximum efficiency but can be uncomfortable, especially for athletes with a narrow waist, as they exert pressure on the ribs and hips during the lifts. Some rare models which are wide on the back and the front but narrower on the sides present a good compromise between comfort and efficiency.

- Weighted clothing, bags of sand, lead shot, or other materials that are strapped to wrists, ankles, torso or other body parts to increase the amount of work required by muscles

- Gloves can improve grip, prevent the formation of calluses on the hands, relieve pressure on the wrists, and provide support.[30]

- Chalk (MgCO3), which dries out sweaty hands, improving grip.

- Wrist and knee wraps.

- Shoes, which have a flat, rigid sole to provide a sturdy base of support, and may feature a raised heel of varying height (usually 0.5" or 0.75") to accommodate a lifter's biomechanics for more efficient squats, deadlifts, overhead presses, and Olympic lifts.

Types of exercises

Isolation exercises versus compound exercises

An isolation exercise is one where the movement is restricted to one joint only. For example, the leg extension is an isolation exercise for the quadriceps. Specialized types of equipment are used to ensure that other muscle groups are only minimally involved—they just help the individual maintain a stable posture—and movement occurs only around the knee joint. Isolation exercises involve machines, dumbbells, barbells (free weights), and pulley machines. Pulley machines and free weights can be used when combined with special/proper positions and joint bracing.

Compound exercises work several muscle groups at once, and include movement around two or more joints. For example, in the leg press, movement occurs around the hip, knee and ankle joints. This exercise is primarily used to develop the quadriceps, but it also involves the hamstrings, glutes and calves. Compound exercises are generally similar to the ways that people naturally push, pull and lift objects, whereas isolation exercises often feel a little unnatural.

Each type of exercise has its uses. Compound exercises build the basic strength that is needed to perform everyday pushing, pulling and lifting activities. Isolation exercises are useful for "rounding out" a routine, by directly exercising muscle groups that cannot be fully exercised in the compound exercises.

The type of exercise performed also depends on the individual's goals. Those who seek to increase their performance in sports would focus mostly on compound exercises, using isolation exercises to strengthen just those muscles that are holding the athlete back. Similarly, a powerlifter would focus on the specific compound exercises that are performed at powerlifting competitions. However, those who seek to improve the look of their body without necessarily maximizing their strength gains (including bodybuilders) would put more of an emphasis on isolation exercises. Both types of athletes, however, generally make use of both compound and isolation exercises.[31]

Free weights versus weight machines

Free weights include dumbbells, barbells, medicine balls, sandbells, and kettlebells. Unlike weight machines, they do not constrain users to specific, fixed movements, and therefore require more effort from the individual's stabilizer muscles. It is often argued that free weight exercises are superior for precisely this reason. For example, they are recommended for golf players, since golf is a unilateral exercise that can break body balances, requiring exercises to keep the balance in muscles.[32]

Some free weight exercises can be performed while sitting or lying on an exercise ball.

There are a number of weight machines that are commonly found in neighborhood gyms. The Smith machine is a barbell that is constrained to vertical movement. The cable machine consists of two weight stacks separated by 2.5 metres, with cables running through adjustable pulleys (that can be fixed at any height so as to select different amounts of weight) to various types of handles. There are also exercise-specific weight machines such as the leg press. A multigym includes a variety of exercise-specific mechanisms in one apparatus.

One limitation of many free weight exercises and exercise machines is that the muscle is working maximally against gravity during only a small portion of the lift. Some exercise-specific machines feature an oval cam (first introduced by Nautilus) which varies the resistance, so that the resistance, and the muscle force required, remains constant throughout the full range of motion of the exercise.

Push-pull workout

A push–pull workout is a method of arranging a weight training routine so that exercises alternate between push motions and pull motions.[33] A push–pull superset is two complementary segments (one pull/one push) done back-to-back. An example is bench press (push) / bent-over row (pull). Another push–pull technique is to arrange workout routines so that one day involves only push (usually chest, shoulders and triceps) exercises, and an alternate day only pull (usually back and biceps) exercises so the body can get adequate rest.[34]

Isotonic and plyometric exercises

These terms combine the prefix iso- (meaning "same") with tonic ("strength") and plio- ("more") with metric ("distance"). In "isotonic" exercises the force applied to the muscle does not change (while the length of the muscle decreases or increases) while in "plyometric" exercises the length of the muscle stretches and contracts rapidly to increase the power output of a muscle.

Weight training is primarily an isotonic form of exercise, as the force produced by the muscle to push or pull weighted objects should not change (though in practice the force produced does decrease as muscles fatigue). Any object can be used for weight training, but dumbbells, barbells, and other specialised equipment are normally used because they can be adjusted to specific weights and are easily gripped. Many exercises are not strictly isotonic because the force on the muscle varies as the joint moves through its range of motion. Movements can become easier or harder depending on the angle of muscular force relative to gravity; for example, a standard biceps curl becomes easier as the hand approaches the shoulder as more of the load is taken by the structure of the elbow. Originating from Nautilus, Inc., some machines use a logarithmic-spiral cam to keep resistance constant irrespective of the joint angle.

Plyometrics exploit the stretch-shortening cycle of muscles to enhance the myotatic (stretch) reflex. This involves rapidly altering the lengthening and shortening of muscle fibers against resistance. The resistance involved is often a weighted object such as a medicine ball or sandbag, but can also be the body itself as in jumping exercises or the body with a weight vest that allows movement with resistance. Plyometrics is used to develop explosive speed, and focuses on maximal power instead of maximal strength by compressing the force of muscular contraction into as short a period as possible, and may be used to improve the effectiveness of a boxer's punch, or to increase the vertical jumping ability of a basketball player. Care must be taken when performing plyometric exercises because they inflict greater stress upon the involved joints and tendons than other forms of exercise.

Health benefits

Benefits of weight training include increased strength, muscle mass, endurance, bone and bone mineral density, insulin sensitivity, GLUT 4 density, HDL cholesterol, improved cardiovascular health and appearance, and decreased body fat, blood pressure, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides.[35]

The body's basal metabolic rate increases with increases in muscle mass, which promotes long-term fat loss and helps dieters avoid yo-yo dieting.[36] Moreover, intense workouts elevate metabolism for several hours following the workout, which also promotes fat loss.[37]

Weight training also provides functional benefits. Stronger muscles improve posture, provide better support for joints, and reduce the risk of injury from everyday activities. Older people who take up weight training can prevent some of the loss of muscle tissue that normally accompanies aging—and even regain some functional strength—and by doing so, become less frail.[38] They may be able to avoid some types of physical disability. Weight-bearing exercise also helps to increase bone density to prevent osteoporosis.[39] The benefits of weight training for older people have been confirmed by studies of people who began engaging in it even in their eighties and nineties.

For many people in rehabilitation or with an acquired disability, such as following stroke or orthopaedic surgery, strength training for weak muscles is a key factor to optimise recovery.[40] For people with such a health condition, their strength training is likely to need to be designed by an appropriate health professional, such as a physiotherapist.

Stronger muscles improve performance in a variety of sports. Sport-specific training routines are used by many competitors. These often specify that the speed of muscle contraction during weight training should be the same as that of the particular sport. Sport-specific training routines also often include variations to both free weight and machine movements that may not be common for traditional weightlifting.

Though weight training can stimulate the cardiovascular system, many exercise physiologists, based on their observation of maximal oxygen uptake, argue that aerobics training is a better cardiovascular stimulus. Central catheter monitoring during resistance training reveals increased cardiac output, suggesting that strength training shows potential for cardiovascular exercise. However, a 2007 meta-analysis found that, though aerobic training is an effective therapy for heart failure patients, combined aerobic and strength training is ineffective; "the favorable antiremodeling role of aerobic exercise was not confirmed when this mode of exercise was combined with strength training".[41]

One side-effect of any intense exercise is increased levels of dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine, which can help to improve mood and counter feelings of depression.[42]

Weight training has also been shown to benefit dieters as it inhibits lean body mass loss (as opposed to fat loss) when under a caloric deficit. Weight training also strengthens bones, helping to prevent bone loss and osteoporosis. By increasing muscular strength and improving balance, weight training can also reduce falls by elderly persons. Weight training is also attracting attention for the benefits it can have on the brain, and in older adults, a 2017 meta analysis found that it was effective in improving cognitive performance.[43]

Weight training and other types of strength training

The benefits of weight training overall are comparable to most other types of strength training: increased muscle, tendon and ligament strength, bone density, flexibility, tone, metabolic rate, and postural support. This type of training will also help prevent injury for athletes. There are benefits and limitations to weight training as compared to other types of strength training. Contrary to popular belief, weight training can be beneficial for both men and women.

Weight training and bodybuilding

Although weight training is similar to bodybuilding, they have different objectives. Bodybuilders use weight training to develop their muscles for size, shape, and symmetry regardless of any increase in strength for competition in bodybuilding contests; they train to maximize their muscular size and develop extremely low levels of body fat. In contrast, many weight trainers train to improve their strength and anaerobic endurance while not giving special attention to reducing body fat far below normal.

The bodybuilding community has been the source of many weight training principles, techniques, vocabulary, and customs. Weight training does allow tremendous flexibility in exercises and weights which can allow bodybuilders to target specific muscles and muscle groups, as well as attain specific goals. Not all bodybuilding is undertaken to compete in bodybuilding contests and, in fact, the vast majority of bodybuilders never compete, but bodybuild for their own personal reasons.[Citation Needed]

Complex training

In complex training, weight training is typically combined with plyometric exercises in an alternating sequence. Ideally, the weight lifting exercise and the plyometric exercise should move through similar ranges of movement i.e. a back squat at 85-95% 1RM followed by a vertical jump. An advantage of this form of training is that it allows the intense activation of the nervous system and increased muscle fibre recruitment from the weight lifting exercise to be utilized in the subsequent plyometric exercise; thereby improving the power with which it can be performed. Over a period of training, this may enhance the athlete's ability to apply power.[44] The plyometric exercise may be replaced with a sports specific action. The intention being to utilize the neural and muscular activation from the heavy lift in the sports specific action, in order to be able to perform it more powerfully. Over a period of training this may enhance the athlete's ability to perform that sports specific action more powerfully, without a precursory heavy lift being required.

Ballistic training

Ballistic training incorporates weight training in such a way that the acceleration phase of the movement is maximized and the deceleration phase minimized; thereby increasing the power of the movement overall. For example, throwing a weight or jumping whilst holding a weight. This can be contrasted with a standard weight lifting exercise where there is a distinct deceleration phase at the end of the repetition which stops the weight from moving.[45]

Contrast loading

Contrast loading is the alternation of heavy and light loads. Considered as sets, the heavy load is performed at about 85-95% 1 repetition max; the light load should be considerably lighter at about 30-60% 1RM. Both sets should be performed fast with the lighter set being performed as fast as possible. The joints should not be locked as this inhibits muscle fibre recruitment and reduces the speed at which the exercise can be performed. The lighter set may be a loaded plyometric exercise such as loaded squat jumps or jumps with a trap bar.

Similarly to complex training, contrast loading relies upon the enhanced activation of the nervous system and increased muscle fibre recruitment from the heavy set, to allow the lighter set to be performed more powerfully.[46] Such a physiological effect is commonly referred to as post-activation potentiation, or the PAP effect. Contrast loading can effectively demonstrate the PAP effect: if a light weight is lifted, and then a heavy weight is lifted, and then the same light weight is lifted again, then the light weight will feel lighter the second time it has been lifted. This is due to the enhanced PAP effect which occurs as a result of the heavy lift being utilised in the subsequent lighter lift; thus making the weight feel lighter and allowing the lift to be performed more powerfully.

Weight training versus isometric training

Isometric exercise provides a maximum amount of resistance based on the force output of the muscle, or muscles pitted against one another. This maximum force maximally strengthens the muscles over all of the joint angles at which the isometric exercise occurs. By comparison, weight training also strengthens the muscle throughout the range of motion the joint is trained in, but only maximally at one angle, causing a lesser increase in physical strength at other angles from the initial through terminating joint angle as compared with isometric exercise. In addition, the risk of injury from weights used in weight training is greater than with isometric exercise (no weights), and the risk of asymmetric training is also greater than with isometric exercise of identical opposing muscles.

See also

References

- Grainger, Luke. "Work Your Entire Body With This Dumbbell Workout". Men's Fitness. Kelsey Media Ltd. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Keogh, Justin W, and Paul W Winwood. “Report for: The Epidemiology of Injuries Across the Weight-Training Sports.” Altmetric – Vitamin C Antagonizes the Cytotoxic Effects of Antineoplastic Drugs, Mar. 2017, summon.altmetric.com/details/8964732.

- "The History of Weightlifting". USA Weightlifting. United States Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

The genealogy of lifting traces back to the beginning of recorded history where man's fascination with physical prowess can be found among numerous ancient writings. A 5,000-year-old Chinese text tells of prospective soldiers having to pass lifting tests.

- "Weightlifting | sport". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- Todd, Jan (1995). From Milo to Milo: A History of Barbells, Dumbbells, and Indian Clubs. Archived 2012-07-31 at the Wayback Machine Iron Game History (Vol.3, No.6).

- "NBC News article on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report on the prevalence of strength training". Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- In the first picture, the knees are too close and get twisted. For appropriate muscular development and safety the knee should be in line with the foot. Rippetoe M, Lon Kilgore (2005). "Knees". Starting Strength. The Aasgard Company. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-0-9768054-0-3.

- "Weight training: Do's and don'ts of proper technique - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- Moore, Marjorie A.; Hutton, Robert S. (1980). "Electromyographic investigation of muscle stretching techniques". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 12 (5): 322–329. doi:10.1249/00005768-198012050-00004. PMID 7453508.

- Herman, Katherine; Barton, Christian; Malliaras, Peter; Morrissey, Dylan (December 2012). "The effectiveness of neuromuscular warm-up strategies, that require no additional equipment, for preventing lower limb injuries during sports participation: a systematic review". BMC Medicine. 10 (1): 75. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-75. PMC 3408383. PMID 22812375.

- McMillian, Danny J.; Moore, Josef H.; Hatler, Brian S.; Taylor, Dean C. (2006). "Dynamic vs. Static-Stretching Warm Up: The Effect on Power and Agility Performance". The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 20 (3): 492–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.455.9358. doi:10.1519/18205.1. PMID 16937960. S2CID 16389590.

- Fleck SJ, Kraemer WJ (2014). Designing resistance training programs (Fourth ed.). Leeds: Human Kinetics. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7360-8170-2.

- "The Right Way to Breathe For More Powerful Weightlifting". Vitals. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- Rippetoe M, Kilgore L (2005). "Squat". Starting Strength. The Aasgard Company. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-0-9768054-0-3.

- McGill, Stuart (2007). "Breathing". Low Back Disorders (2d ed.). Human Kinetics. pp. 186–7.

- "Water, Water, Everywhere". WebMD.

- Mark Dedomenico. "Metabolism Myth #5". MSN Health.

- American College of Sports Medicine; Sawka, MN; Burke, LM; Eichner, ER; Maughan, RJ; Montain, SJ; Stachenfeld, NS (February 2007). "American College of Sports Medicine position stand: Exercise and fluid replacement" (PDF). Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 39 (2): 377–390. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e31802ca597. PMID 17277604. S2CID 400815.

- Nancy Cordes (2008-04-02). "Busting The 8-Glasses-A-Day Myth". CBS.

- ""Drink at Least 8 Glasses of Water a Day" - Really?". Dartmouth Medical School.

- Johnson-Cane et al., p. 75

- Johnson-Cane et al., p. 76

- "Hydration and Exercise - What to Drink for Proper Hydration During Exercise". Sportsmedicine.about.com. 2011-04-15. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- McCarthy M (2009-07-06). "Overuse of energy drinks worries health pros". USA Today.

- Johnson-Cane et al., p. 153

- "7 tips for a safe and successful strength-training program". Harvard Health Publishing. Harvard Health. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- "Find your fit: Weight training". Arkansas Business. 35 (4): S30–S31. 2018. ProQuest 1994247717.

- "Is Training To Failure Necessary?". Training Science. 2012-03-27. Archived from the original on 2017-04-01. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- Kingma, Idsart; Faber, Gert S.; Suwarganda, Edin K.; Bruijnen, Tom B. M.; Peters, Rob J. A.; van Dieën, Jaap H. (October 2006). "Effect of a Stiff Lifting Belt on Spine Compression During Lifting". Spine. 31 (22): E833–E839. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000240670.50834.77. PMID 17047531. S2CID 22138551.

- "The benefits of wearing weight lifting gloves".

- Henselmans, Menno. “Compound vs. Isolation Exercises: Which Is Best? [Study Review].” MennoHenselmans.com, 16 Jan. 2019, mennohenselmans.com/compound-vs-isolation-exercise/.

- Ahn Hyejung (November 11, 2012), World Class Fitness Trainers, John Sitaras, Golf Digest (Korean edition)

- Frontera WR, Slovik DM, Dawson DM (2006). Exercise in Rehabilitation Medicine. Human Kinetics, 2006. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-7360-5541-3.

- "Push-Pull Training". FLEX Online. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- Westcott, Wayne L. (2012). "Resistance Training is Medicine: Effects of Strength Training on Health". Current Sports Medicine Reports. 11 (4): 209–216. doi:10.1249/JSR.0b013e31825dabb8. PMID 22777332. S2CID 11977370.

- "Fat Loss Article: Metabolism Myth". cbass.com.

- Meirelles, Cláudia de Mello; Gomes, Paulo Sergio Chagas (April 2004). "Efeitos agudos da atividade contra-resistência sobre o gasto energético: revisitando o impacto das principais variáveis". Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. 10 (2): 122–130. doi:10.1590/S1517-86922004000200006.

- Mayer, Frank; Scharhag-Rosenberger, Friederike; Carlsohn, Anja; Cassel, Michael; Müller, Steffen; Scharhag, Jürgen (27 May 2011). "The Intensity and Effects of Strength Training in the Elderly". Deutsches Ärzteblatt Online. 108 (21): 359–364. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2011.0359. PMC 3117172. PMID 21691559.

- Layne, Jennifer E.; Nelson, Miriam E. (January 1999). "The effects of progressive resistance training on bone density: a review". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 31 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1097/00005768-199901000-00006. PMID 9927006.

- Ada, Louise; Dorsch, Simone; Canning, Colleen G. (2006). "Strengthening interventions increase strength and improve activity after stroke: a systematic review". Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 52 (4): 241–248. doi:10.1016/s0004-9514(06)70003-4. PMID 17132118.

- Haykowsky, Mark J.; Liang, Yuanyuan; Pechter, David; Jones, Lee W.; McAlister, Finlay A.; Clark, Alexander M. (June 2007). "A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Exercise Training on Left Ventricular Remodeling in Heart Failure Patients". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 49 (24): 2329–2336. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.055. PMID 17572248.

- "Exercise and Depression". WebMD.

- Northey, Joseph Michael; Cherbuin, Nicolas; Pumpa, Kate Louise; Smee, Disa Jane; Rattray, Ben (February 2018). "Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 52 (3): 154–160. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096587. PMID 28438770.

- Fleck SJ, Kraemer WJ (2013). "Complex Training, or Contrast Loading". Designing Resistance Training Programmes. Leeds: Human Kinetics. p. 253.

- Fleck SJ, Kraemer WJ (2013). "Ballistic Training". Designing Resistance Training Programmes. Leeds: Human Kinetics. p. 280.

- McGuigan M (2017). "Contrast Training". Developing Power. Leeds: Human Kinetics. pp. 196–197.

Bibliography

- Delavier F (2001). Strength Training Anatomy. Human Kinetics Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7360-4185-0.

- DeLee J, Drez D (2003). DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine; Principles and Practice. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-8845-9.

- Hatfield F (1993). Hardcore Bodybuilding: A Scientific Approach. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-8092-3728-9.

- Kennedy R, Weis D (1986). Mass!, New Scientific Bodybuilding Secrets. Contemporary Books. ISBN 978-0-8092-4940-4.

- Lombardi VP (1989). Beginning Weight Training. Wm. C. Brown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-697-10696-4.

- Powers S, Howley E (2003). Exercise Physiology. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-255728-2.

- Schoenfeld, Brad (2002). Sculpting Her Body Perfect. Human Kinetics Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7360-4469-1.

- Schwarzenegger A (1999). The New Encyclopedia of Modern Bodybuilding. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-85721-3.

- McGill S (2007). Low Back Disorders (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. ISBN 978-0-7360-6692-1.

- McGill S (2009). Ultimate Back Fitness And Performance (4th ed.). Waterloo, Ontario: Backfitpro Inc. ISBN 978-0-9735018-1-0.