Science of yoga

The science of yoga is the scientific basis of modern yoga as exercise in human sciences such as anatomy, physiology, and psychology. Yoga's effects are to some extent shared with other forms of exercise,[O 1] though it differs in the amount of stretching involved, and because of its frequent use of long holds and relaxation, in its ability to reduce stress. Yoga is here treated separately from meditation, which has effects of its own, though yoga and meditation are combined in some schools of yoga.

Yoga has been studied scientifically since the 19th century physiology experiments of N. C. Paul. The early 20th century pioneers Yogendra and Kuvalayananda both set up institutes to study yoga systematically.

Yoga helps to maintain bone strength, joint mobility, and joint stability. It improves posture, muscle strength, coordination, and confidence, in turn reducing the risk of injury and bone fracture. As it is generally slow and conducted with awareness, it may be safer than many other sports; but some postures such as headstand, shoulderstand, and lotus position have been reported as causes of injury.

Yoga is also used directly as therapy, especially for psychological conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, but the evidence for this remains weak. Yoga has sometimes been marketed with pseudoscientific claims for specific benefits, when it may be no better than other forms of exercise in those cases;[O 1] and some claims for its effects on particular organs, such as that forward bends eject toxins from the liver, are entirely unfounded. Reviewers have noted the need for more high-quality studies of yoga's effects.

History

In the 19th century, the Bengali physician N. C. Paul began the study of the physiology of yoga with his 1851 book Treatise on Yoga Philosophy, noting that yoga can raise carbon dioxide levels in the blood (hypercapnia).[2][3][4]

Early in the 20th century, two pioneers of yoga as exercise in India, Yogendra and Kuvalayananda, worked to make Haṭha yoga acceptable, seeking scientific evidence for the health benefits of yoga postures (asanas) and yoga breathing (pranayama). In 1918, Yogendra founded The Yoga Institute to carry out research on yoga, hoping that a gloss of science would make yoga more acceptable in the West.[P 1][O 2][5] Yogendra expressed his intentions in books such as his 1928 Yoga Asanas Simplified[6] and his 1931 Yoga Personal Hygiene.[7] In 1924, Kuvalayananda founded the Kaivalyadhama Health and Yoga Research Center, combining asanas with gymnastics, and like Yogendra seeking a scientific and medical basis for yogic practices.[8][9]

In 1937, the Yale physiologist Kavoor T. Behanan published his book Yoga: A Scientific Evaluation, reporting that a form of pranayama, Ujjayi ("Victorious breath"), performed at the slow rate of 28 breaths in 22 minutes, could create a deeply relaxed state that he called "an extremely pleasant feeling of quietude",[10] accompanied by a marked slowing of mental performance on tests such as mental sums, recognising colours and solving simple puzzles. The science journalist William Broad notes that this finding contradicted the image of yoga as conferring special powers.[11][10]

Scope

Yoga as exercise is defined by Merriam-Webster as "a system of physical postures, breathing techniques, and sometimes meditation derived from [traditional] Yoga but often practiced independently especially in Western cultures to promote physical and emotional well-being".[O 3]

The science journalist William Broad notes that yoga has "wide health benefits",[12] and defines the scope of the science of yoga as to "better understand what yoga can do and better understand what yoga can be".[13] He distinguishes "the modern variety" which is his subject from the Haṭha yoga that formed "in medieval times".[13][lower-alpha 1] Denise Rankin-Box, editor of Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, one of several Elsevier journals that publish papers on the effects of yoga (among other matters), offers the definition "research addressing the impact of yoga on health and wellbeing."[O 5] Ann Swanson, an educator and yoga therapist, writes that "scientific principles and evidence have demystified so much of the practice" of yoga;[14] her book on the Science of Yoga is principally about the anatomy of yoga asanas,[15] with a chapter on the relationships of the body's systems (anatomy and physiology) to yoga.[16] Psychiatric researchers such as Michaela Pascoe have addressed the effect of yoga on measures of psychological stress and depression.[P 2][P 3]

Broad notes the "diffuse nature of the existing science"[13] with pieces of the metaphorical jigsaw puzzle of scientific knowledge of what yoga actually achieves held in many laboratories around the world. The picture is, Broad writes, confused by the "predatory behaviour"[17] of commercial ventures intent upon promoting themselves;[17] but is being clarified by the American National Institutes of Health, which began funding scientific research into yoga in 1998, leading to reliable reports of studies of yoga's effects on different conditions.[18]

Physical effects

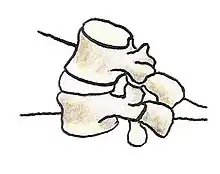

Skeleton and joints

Yoga helps to keep bones and joints in a healthy state.[19] In particular, it helps to maintain bone strength;[20] it also helps to maintain both joint mobility (range of motion), and joint stability.[21][22] It improves posture, muscular strength, coordination and confidence (reducing anxiety), all of which reduce the risk of injury and bone fracture, and which may therefore be helpful to people with conditions such as osteoporosis.[O 6] On the other hand, yoga, like any other physical activity, can result in injury; headstand (Sirsasana), shoulder stand (Sarvangasana), and lotus position (Padmasana) are the asanas most often reported as causes of injury.[P 5] Ann Swanson offers three reasons why yoga may be safer than many sports, namely that it is often slow; it encourages awareness in the moment; and it stresses doing no harm (ahimsa).[23] The American National Institutes of Health advise practising with a qualified instructor to reduce the chance of injury.[24]

Muscles

Yoga involves both isotonic activity, the shortening of muscles under load, and (unlike many forms of exercise) also a substantial amount of isometric activity, holding still under load, as in any asana which is held for a period. Isometric exercise builds muscle strength.[25]

One of the applications of science to yoga is the provision of detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the skeletomuscular system, as it relates to yoga asanas, for yoga teachers and yoga therapists.[26][27][28]

Breathing

.JPG.webp)

Breathing and posture affect each other, especially through their effects on the diaphragm.[29] Breathing also affects the autonomic nervous system; quiet breathing slows the heart and reduces blood pressure. Together, these produce a feeling of calmness and relaxation.[30] One way to do this is used in one form of yoga breathing (pranayama): the exhalation is counted to be twice as long as the inhalation, say inhale to a count of 3 and exhale to a count of 6.[31]

Breathing can equally be used to energise the body. The pranayama method of bhastrika (bellows breath) and the satkarma purification of kapalabhati (skull polishing) both energise the body with vigorous abdominal breathing, using the diaphragm to make the abdomen move in and out.[32]

Broad notes the "myth" that yoga, and especially pranayama, increases the supply of oxygen to the body. He writes that instead, fast vigorous breathing as with bhastrika may indeed feel exhilarating, as B. K. S. Iyengar reported, but it lowers the level of carbon dioxide in the blood. This causes blood vessels in the brain to constrict, reducing the brain's uptake of oxygen, resulting in symptoms such as dizziness and fainting. On the other hand, slow pranayama can raise carbon dioxide levels, and increase the uptake of oxygen by the brain.[33]

Physiological effects

Fitness

Yoga can be used as exercise to help maintain physical fitness. A complete yoga session with asanas and pranayama provides on average a moderate workout.[lower-alpha 2] Surya Namaskar (the 12-asana Salute to the Sun sequence) ranged from light to vigorous exercise, depending on how it was performed.[lower-alpha 3] The average for a session of yoga practice without Surya Namaskar was light or moderate exercise.[lower-alpha 4][P 6][P 7]

Cardiovascular health

A 2012 survey of yoga in Australia notes that there is "good evidence"[P 8][P 9] that both yoga on its own, and its associated healthy lifestyle—often vegetarian, usually non-smoking, preferring organic food, drinking less or no alcohol—are beneficial for cardiovascular health, but that there was "little apparent uptake of yoga to address [existing] cardiovascular conditions and risk factors".[P 8] Yoga was cited by respondents as a cause of these lifestyle changes; the survey notes that the relative importance of the various factors had not been assessed.[P 8]

Stress relief

Yoga sessions often end (and sometimes also begin) with a period of relaxation in corpse pose, Savasana. The activity levels of all the body's muscles, and the motor neurons (nerve cells) that activate them, is reduced as relaxation is practised, except for the diaphragm which is used in breathing; and the breathing rate reduces also.[34]

Yoga has other measurable effects that may be beneficial; for example, it reduces the level of the stress hormone cortisol.[35]

As therapy

Systematic review has found strong evidence for beneficial effects of yoga as an additional therapy on low back pain[P 4] and to some extent for psychological conditions such as stress and depression,[P 2][P 3] but despite repeated attempts, little or no evidence for benefit for specific medical conditions. Much of the research on the therapeutic use of yoga, including for depression, has been in the form of preliminary studies or clinical trials of low methodological quality, suffering from small sample sizes, inadequate control and blinding, lack of randomization, and high risk of bias.[P 11][P 12] For example, study of trauma-sensitive yoga has been hampered by weak methodology.[P 13]

Pseudoscience

The neurologist and sceptic Steven Novella states that "Yoga .. fits into a more general phenomenon of marketing a specific intervention as if it has specific benefits, when in fact it only has generic benefits."[O 1] He gives as an example the evidence that yoga helps to relieve low back pain, but that with "a lack of quality studies [by 2013] comparing yoga to other forms of exercise",[O 1] it is possible that yoga's benefits are just what any form of exercise would provide, generically. Novella points out that yoga also has a spiritual side, so claims made for it can mix science with "a liberal dose of pure pseudoscience and mysticism."[O 1] He illustrates this by quoting unfounded claims such as that a forward bend squeezes the pancreas and liver, ejecting toxins, and that stretching the lower back is calming because emotional stress accumulates in the lower back muscles. Novella states that "None of those specific claims is based in reality."[O 1] The practice of yoga for children is similarly lacking rigorous study.[P 14]

Notes

- The LiveScience website similarly states "Modern-day science confirms that the practice also has tangible physical benefits to overall health benefits".[O 4]

- Measured at 3.3 ± 1.6 METs.[P 6]

- Larson-Meyer and Enette found a range of 2.9 (light exercise) to 7.4 (vigorous) METs. Curious about the wide range of METs in Surya Namaskar, repeated the study (Mody) which gave the highest value; using "transition jumps, and full pushups", he obtained "agreement" with 6.4 METs.[P 6]

- Asanas performed individually provide on average 2.2 ± 0.7 METs; pranayama types performed individually provide just 1.3 ± 0.3 METs; a combined class provided 2.9 ± 0.8 METs.[P 6]

References

Books

- Alter 2004, pp. 81–100.

- Broad 2012, pp. 20ff.

- Singleton 2010, p. 52.

- Paul 1882.

- Shearer 2020, p. 251.

- Yogendra 1928.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 116–117.

- Alter 2004, p. 31.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 100–141.

- Broad 2012, pp. 83-85.

- Behanan 2002.

- Broad 2012, p. 54.

- Broad 2012, p. 217.

- Swanson 2019, pp. 6-7.

- Swanson 2019, pp. 42-173.

- Swanson 2019, pp. 10-41.

- Broad 2012, p. 218.

- Broad 2012, p. 219.

- Swanson 2019, p. 12.

- Swanson 2019, p. 118.

- Powers 2008, pp. 25, 176.

- Swanson 2019, p. 63.

- Swanson 2019, p. 202.

- "Yoga: What You Need To Know". National Institutes of Health. May 2019.

- Coulter 2007, Chapter 1. Movement: Isotonic and Isometric Activity.

- Kaminoff & Matthews 2012.

- Long & Macivor 2009.

- Swanson 2019.

- Coulter 2007, Chapter 2. Breathing. How Breathing Affects Posture.

- Coulter 2007, Chapter 2. Breathing. How Breathing Affects The Autonomic Nervous System.

- Coulter 2007, Chapter 2. Breathing. 2:1 Breathing.

- Coulter 2007, Chapter 2. Breathing. The Bellows Breath and Kapalabhati.

- Broad 2012, pp. 85-89.

- Coulter 2007, Chapter 10. Relaxation and Meditation. The Corpse Posture.

- Swanson 2019, p. 27.

Scientific papers

- Newcombe, Suzanne (2017). "The Revival of Yoga in Contemporary India" (PDF). Religion. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. 1. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.253. ISBN 9780199340378.

- Pascoe, Michaela C.; Bauer, Isabelle E. (1 September 2015). "A systematic review of randomised control trials on the effects of yoga on stress measures and mood". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 68: 270–282. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.07.013. PMID 26228429.

- Cramer, Holger; Anheyer, Dennis; Lauche, Romy; Dobos, Gustav (2017). "A systematic review of yoga for major depressive disorder". Journal of Affective Disorders. 213: 70–77. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.006. hdl:10453/79255. ISSN 0165-0327. PMID 28192737.

- Cramer, Holger; Lauche, Romy; Haller, Heidemarie; Dobos, Gustav (2013). "A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Yoga for Low Back Pain". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 29 (5): 450–460. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492. PMID 23246998.

- Acott, Ted S.; Cramer, Holger; Krucoff, Carol; Dobos, Gustav (2013). "Adverse Events Associated with Yoga: A Systematic Review of Published Case Reports and Case Series". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e75515. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075515. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3797727. PMID 24146758.

- Larson-Meyer, D. Enette (2016). "A Systematic Review of the Energy Cost and Metabolic Intensity of Yoga". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 48 (8): 1558–1569. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000922. ISSN 0195-9131. PMID 27433961.

- Haskell, William L.; et al. (2007). "Physical Activity and Public Health". Circulation. 116 (9): 1081–1093. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185649. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 17671237.

- Penman, Stephen; Stevens, Philip; Cohen, Marc; Jackson, Sue (2012). "Yoga in Australia: Results of a national survey". International Journal of Yoga. 5 (2): 92–101. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.98217. ISSN 0973-6131. PMC 3410203. PMID 22869991.

- Jayasinghe, S. R. (2004). "Yoga in cardiac health (A Review)". European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. 11 (5): 369–375. doi:10.1097/01.hjr.0000206329.26038.cc. ISSN 1741-8267. PMID 15616408.

- Riley, Kristen E.; Park, Crystal L. (2015). "How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry". Health Psychology Review. 9 (3): 379–396. doi:10.1080/17437199.2014.981778. PMID 25559560.

- Krisanaprakornkit, T.; Ngamjarus, C.; Witoonchart, C.; Piyavhatkul, N. (2010). "Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD006507. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2. PMC 6823216. PMID 20556767.

- Uebelacker, L. A.; Epstein-Lubow, G.; Gaudiano, B. A.; Tremont, G.; Battle, C. L.; Miller, I. W. (2010). "Hatha yoga for depression: critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 16 (1): 22–33. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. PMID 20098228.

- Nguyen-Feng, Viann N.; Clark, Cari J.; Butler, Mary E. (August 2019). "Yoga as an intervention for psychological symptoms following trauma: A systematic review and quantitative synthesis". Psychological Services. 16 (3): 513–523. doi:10.1037/ser0000191. PMID 29620390.

- Smith, Bradley H.; Mendelson, Tamar (2014). "Special issue on yoga and mindfulness interventions in schools". Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 7 (3): 137–139. doi:10.1080/1754730X.2014.920131. ISSN 1754-730X.

Other

- Novella, Steven (31 July 2013). "Yoga Woo". Science-Based Medicine.

- Mishra, Debashree (3 July 2016). "Once Upon A Time: From 1918, this Yoga institute has been teaching generations, creating history". Indian Express. Mumbai.

- "Yoga". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Salamon, Maureen (30 May 2013). "The Science of Yoga and Why It Works". LiveScience.

- Rankin-Box, Denise (18 June 2015). "The science of yoga — what research reveals". Elsevier.

- Brody, Jane E. (21 December 2015). "12 Minutes of Yoga for Bone Health". The New York Times.

Book sources

- Alter, Joseph (2004). Yoga in Modern India : the body between science and philosophy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11874-1.

- Behanan, Kovoor T. (2002) [1937]. Yoga: Its Scientific Basis. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-41792-9. originally titled Yoga: A Scientific Evaluation.

- Broad, William (2012). The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4142-4.

- Coulter, H. David (2007) [2001]. Anatomy of Hatha Yoga: A Manual for Students, Teachers, and Practitioners. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1965-8.

- Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga : the history of an embodied spiritual practice. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5.

- Kaminoff, Leslie; Matthews, Amy (2012) [2007]. Yoga Anatomy (2nd ed.). The Breath Trust. ISBN 978-1-4504-0024-4.

- Long, Ray; Macivor, Chris (2009). Scientific Keys: The Key Muscles of Yoga Volume 1. Bandha Yoga. ISBN 978-1-60743-238-8.

- Paul, N. C. (1882) [1851]. Treatise on Yoga Philosophy. E. J. Lazarus and Co., Medical Hall Press.

- Powers, Sarah (2008). Insight Yoga. Shambhala. ISBN 978-1-59030-598-0. OCLC 216937520.

- Shearer, Alistair (2020). Story of Yoga : from Ancient India to the Modern West. C. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-78738-192-6. OCLC 1089012347.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1.

- Swanson, Ann (2019). Science of Yoga : understand the anatomy and physiology to perfect your practice. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4654-7935-8.

- Yogendra (1928). Yoga Asanas Simplified. The Yoga Institute.