Muezzin

The English word muezzin, derived from the Arabic: مُؤَذِّن, muʾadh·dhin [mu.ʔað.ðin], simplified mu'azzin,[1] is the person appointed at a mosque to lead and recite the call to prayer for every event of prayer[2] and worship in the mosque. The muezzin's post is an important one, and the community depends on him for an accurate prayer schedule.

.JPG.webp)

Etymology

The word means "one by the ear", since the word stems from the word for "ear" in Arabic is ʾudhun (أُذُن). As the muʾadh·dhin will place both hands on his ears to recite the call to prayer.

Roles and responsibilities

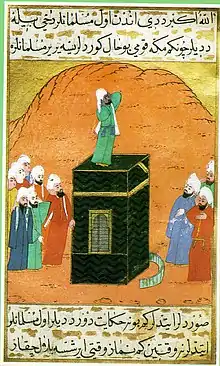

The professional muezzin is chosen for his good character, voice and skills to serve at the mosque. However, the muezzin is not considered a cleric, but in a position comparable to a Christian verger. He is responsible for keeping the mosque clean, for rolling the carpets, for cleaning the toilets and the place where people wash their hands, face and feet when they perform the Wuḍu' (Arabic: wuḍū’ وُضُوء, the "purification" of ablution) before offering the prayer. When calling to prayer, the muezzin faces the qiblah, the direction of the Ka'bah in Makkah, while reciting the adhan.[3]

From the fourteenth history, initially in Mamluk Egypt but then spread into other parts of the Islamic world, major mosques might employ a related officer, the muwaqqit, who determined the prayer times using mathematical astronomy. Unlike the muezzin who were typically chosen for their piety and beautiful voice, the qualification of the muwaqqit required special knowledge in astronomy.[4][5] Historian Sonja Brentjes speculates that the muwaqqit might have evolved from a specialised muezzin,[6] and that there might not have been a clear delineation between the two offices.[7] Some celebrated muwaqqits, including Shams al-Din al-Khalili and ibn al-Shatir, were known to have once been muezzins, and many individuals held both offices simultaneously.[8] Today, with the production of electronic devices and authoritative timetables, a muezzin in a mosque can broadcast the call to prayer by consulting a table or a clock without requiring the specialised skill of a muwaqqit.[9]

Call of the muezzin

The call of the muezzin is considered an art form, reflected in the melodious chanting of the adhan. In Turkey there is an annual competition to find the country's best muezzin.[10]

Historically, a muezzin would have recited the call to prayer atop the minarets in order to be heard by those around the mosque. Now, mosques often have loudspeakers mounted on the top of the minaret and the muezzin will use a microphone, or a recording is played, allowing the call to prayer to be heard at great distances without climbing the minaret.

Origins

The institution of the muezzin has existed since the time of Muhammad. The first muezzin was a former slave Bilal ibn Rabah, one of the most trusted and loyal Sahabah (companions) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He was born in Mecca and is considered to have been the first mu'azzin, chosen by Muhammad himself.[11][12][13][14]

Although many of the customs associated with the muezzin remained undecided at the time of Muhammad's death, including which direction one should choose for the calling, where it should be performed, and the use of trumpets, flags or lamps, all of these are elements of the muezzin's role during the adhan.

After minarets became customary at mosques, the office of muezzin in cities was sometimes given to a blind man, who could not see down into the inner courtyards of the citizens' houses and thus could not violate privacy. Whether factual or not, the blindness of muezzin is claimed as almost universal at certain periods by Jose Saramago in his novel concerning historical epistemology, The History of the Siege of Lisbon.

Notable muezzins

See also

- Salah or salat, Muslim daily prayer

- Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, recited by the muuezzin

- Schulklopfer, the Jewish equivalent of the muuezzin

- Loudspeakers in mosques

References

- "muezzin". Dictionary.com.

- Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi (26 March 2016). The Laws of Islam (PDF). Enlight Press. p. 470. ISBN 978-0994240989. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- A Muazzin calling for prayer in Saudi Arabia

- King 1996, p. 286.

- Pedersen 1991, p. 677.

- Brentjes 2008, p. 139.

- Brentjes 2008, p. 141.

- Brentjes 2008, pp. 139–140.

- King 1996, p. 322.

- "Muezzin". Aljazeera. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Ludwig W. Adamec (2009), Historical Dictionary of Islam, p.68. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810861615.

- Robinson, David. Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Print.

- Levtzion, Nehemia, and Randall Lee Pouwels. The History of Islam in Africa. South Africa: Ohio UP, 2000. Print.

Bibliography

- Brentjes, Sonja (2008). "Shams al-Din al-Sakhawi on Muwaqqits, Mu'adhdhins, and the Teachers of Various Astronomical Disciplines in Mamluk Cities in the Fifteenth Century". In Emilia Calvo; Mercè Comes; Roser Puig; Mònica Rius (eds.). A Shared Legacy: Islamic Science East and West. Edicions Universitat Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-475-3285-8.

- King, David A. (1996). "On the role of the muezzin and the muwaqqit in medieval Islamic society". In E. Jamil Ragep; Sally P. Ragep (eds.). Tradition, Transmission, Transformation. E.J. Brill. pp. 285–345. ISBN 90-04-10119-5.

- Pedersen, Johannes (1991). "Masdjid: The personnel of the mosque". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 674–677. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muezzins. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "Muezzin". |