Liberalism and progressivism within Islam

Liberalism and progressivism within Islam involve professed Muslims who have created a considerable body of liberal thought about Islamic understanding and practice.[1] Their work is sometimes characterized as "progressive Islam" (Arabic: الإسلام التقدمي al-Islām at-taqaddumī); some scholars, such as Omid Safi, regard progressive Islam and liberal Islam as two distinct movements.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

| Islam and other religions |

|---|

|

| Abrahamic religions |

| Other religions |

| Islam and... |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

|

Liberal ideas are considered controversial by some traditional Muslims, who criticize liberal ideas on the grounds of being too Western or rationalistic.[3]

The methodologies of liberal or progressive Islam rest on the interpretation of traditional Islamic scripture (the Quran) and other texts (such as the Hadith), a process called ijtihad (see below).[4] This can vary from the slight to the most liberal, where only the meaning of the Quran is considered to be a revelation, with its expression in words seen as the work of the prophet Muhammad in his particular time and context.

Liberal Muslims see themselves as returning to the principles of the early Ummah ethical and pluralistic intent of the Quran.[5] They distance themselves from some traditional and less liberal interpretations of Islamic law which they regard as culturally based and without universal applicability. The reform movement uses monotheism (tawhid) "as an organizing principle for human society and the basis of religious knowledge, history, metaphysics, aesthetics, and ethics, as well as social, economic and world order".[6]

Liberal Islam values reinterpretations of the Islamic scriptures in order to preserve their relevance in the 21st century.[7]

Background in Islamic philosophy

The rise of Islam, based on both the Qur'an and Muhammad, strongly altered the power balances and perceptions of origin of power in the Mediterranean region. Early Islamic philosophy emphasized an inexorable link between science and religion, and the process of ijtihad to find truth—in effect all philosophy was "political" as it had real implications for governance. This view was challenged by the "rationalist" Mutazilite philosophers, who held a more Hellenic view, reason above revelation, and as such are known to modern scholars as the first speculative theologians of Islam; they were supported by a secular aristocracy who sought freedom of action independent of the Caliphate. By the late ancient period, however, the "traditionalist" Asharite view of Islam had in general triumphed. According to the Asharites, reason must be subordinate to the Quran and the Sunnah.[8]

Ibn Rushd, often Latinized as Averroes, was a medieval Andalusian polymath. Being described as "founding father of secular thought in Western Europe",[9][10] he was known by the nickname the Commentator for his precious commentaries on Aristotle's works. His main work was The Incoherence of the Incoherence in which he defended philosophy against al-Ghazali's claims in The Incoherence of the Philosophers. His other works were the Fasl al-Maqal and the Kitab al-Kashf.[9][10] Ibn Rushd presented an argument in Fasl al-Maqal (Decisive Treatise) providing a justification for the emancipation of science and philosophy from official Ash'ari theology and that there is no inherent contradiction between philosophy and religion; thus Averroism has been considered a precursor to modern secularism.[11][12][13] Ibn Rushd accepts the principle of women's equality. According to him they should be educated and allowed to serve in the military; the best among them might be tomorrow's philosophers or rulers.[14][15] The 13th-century philosophical movement in Latin Christian and Jewish tradition based on Ibn Rushd's work is called Averroism. Ibn Rushd became something of a symbolic figure in the debate over the decline and proposed revitalization of Islamic thought and Islamic society in the later 20th century. A notable proponent of such a revival of Averroist thought in Islamic society was Mohammed Abed al-Jabri with his Critique de la Raison Arabe (1982).[16]

In 1831, Egyptian Egyptologist and renaissance intellectual Rifa'a al-Tahtawi was part of the statewide effort to modernize the Egyptian infrastructure and education. They introduced his Egyptian audience to Enlightenment ideas such as secular authority and political rights and liberty; his ideas regarding how a modern civilized society ought to be and what constituted by extension a civilized or "good Egyptian"; and his ideas on public interest and public good.[17] Tahtawi's work was the first effort in what became an Egyptian renaissance (nahda) that flourished in the years between 1860 and 1940.[18]

Tahtawi is considered one of the early adapters to Islamic Modernism. Islamic Modernists attempted to integrate Islamic principles with European social theories. In 1826, Al-Tahtawi was sent to Paris by Mehmet Ali. Tahtawi studied at an educational mission for five years, returning in 1831. Tahtawi was appointed director of the School of Languages. At the school, he worked translating European books into Arabic. Tahtawi was instrumental in translating military manuals, geography, and European history.[19] In total, al-Tahtawi supervised the translation of over 2,000 foreign works into Arabic. Al-Tahtawi even made favorable comments about French society in some of his books.[20] Tahtawi stressed that the Principles of Islam are compatible with those of European Modernity.

In his piece, The Extraction of Gold or an Overview of Paris, Tahtawi discusses the patriotic responsibility of citizenship. Tahtawi uses Roman civilization as an example for what could become of Islamic civilizations. At one point all Romans are united under one Caesar but split into East and West. After splitting, the two nations see “all its wars ended in defeat, and it retreated from a perfect existence to nonexistence.” Tahtawi understands that if Egypt is unable to remain united, it could fall prey to outside invaders. Tahtawi stresses the importance of citizens defending the patriotic duty of their country. One way to protect one's country according to Tahtawi, is to accept the changes that come with a modern society.[21]

Egyptian Islamic jurist and religious scholar Muhammad Abduh, regarded as one of the key founding figures of Islamic Modernism or sometimes called Neo-Mu’tazilism,[22] broke the rigidity of the Muslim ritual, dogma, and family ties.[23] Abduh argued that Muslims could not simply rely on the interpretations of texts provided by medieval clerics, they needed to use reason to keep up with changing times. He said that in Islam man was not created to be led by a bridle, man was given intelligence so that he could be guided by knowledge. According to Abduh, a teacher's role was to direct men towards study. He believed that Islam encouraged men to detach from the world of their ancestors and that Islam reproved the slavish imitation of tradition. He said that the two greatest possessions relating to religion that man was graced with were independence of will and independence of thought and opinion. It was with the help of these tools that he could attain happiness. He believed that the growth of western civilization in Europe was based on these two principles. He thought that Europeans were roused to act after a large number of them were able to exercise their choice and to seek out facts with their minds.[24] In his works, he portrays God as educating humanity from its childhood through its youth and then on to adulthood. According to him, Islam is the only religion whose dogmas can be proven by reasoning. He was against polygamy and thought that it was an archaic custom. He believed in a form of Islam that would liberate men from enslavement, provide equal rights for all human beings, abolish the religious scholar's monopoly on exegesis and abolish racial discrimination and religious compulsion.[25]

Muhammad Abduh claimed in his book "Al-Idtihad fi Al-Nasraniyya wa Al-Islam[26]" that no one had exclusive religious authority in the Islamic world. He argued that the Caliph did not represent religious authority, because he was not infallible nor was the Caliph the person whom the revelation was given to; therefore, according to Abduh, the Caliph and other Muslims are equal. ʿAbduh argued that the Caliph should have the respect of the ummah but not rule it; the unity of the umma is a moral unity which does not prevent its division into national states.[27]

Mohammad Abduh made great efforts to preach harmony between Sunnis and Shias. Broadly speaking, he preached brotherhood between all schools of thought in Islam.[28] Abduh regularly called for better friendship between religious communities. As Christianity was the second biggest religion in Egypt, he devoted special efforts towards friendship between Muslims and Christians. He had many Christian friends and many a time he stood up to defend Copts.[28]

Egyptian Qur'anic thinker, author, academic Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd is one of the leading liberal theologians in Islam. He is famous for his project of a humanistic Qur'anic hermeneutics, which "challenged mainstream views" on the Qur'an sparking "controversy and debate."[29] While not denying that the Qur'an was of divine origin, Zayd argued that it was a "cultural product" that had to be read in the context of the language and culture of seventh century Arabs,[30] and could be interpreted in more than one way.[31] He also criticized the use of religion to exert political power.[32] In 1995 an Egyptian Sharia court declared him an apostate, this led to threats of death and his fleeing Egypt several week later.[32] (He later "quietly" returned to Egypt where he died.[32])

According to scholar Navid Kermani "three key themes" emerge from Abu Zayd's work:

- to trace the various interpretations and historical settings of the single Qur'anic text from the early days of Islam up to the present;

- to demonstrate the "interpretational diversity" (al-ta 'addud alta 'wili)[33] that exists within the Islamic tradition;

- and to show how this diversity has been "increasingly neglected" across Islamic history.[31]

Abu Zayd saw himself as an heir to the Muʿtazila, "particularly their idea of the created Qurʿān and their tendency toward metaphorical interpretation."[34]

Abu Zayd strongly opposed the belief in a "single, precise and valid interpretation of the Qur'an handed down by the Prophet for all times".[35]

In his view, the Quran made Islamic Arab culture a `culture of the text` (hadarat al-nass) par excellence, but because the language of the Quran is not self-explanatory, this implied Islamic Arab culture was also a culture of interpretation (hadarat al-ta'wil).[36] Abu Zayd emphasized "intellect" (`aql) in understanding the Quran, as opposed to "a hermeneutical approach which gives priority to the narrated traditions [ hadith ]" (naql). As a reflection of this Abu Zaid used the term ta'wil (interpretation) for efforts to understand the Quran, while in the Islamic sciences, the literature that explained the Quran was referred to as tafsir (commentary, explanation).[37]

For Abu Zaid, interpretation goes beyond explanation or commentary, "for without" the Qur'an would not have meaning:

The [Qur'anic] text changed from the very first moment - that is, when the Prophet recited it at the moment of its revelation - from its existence as a divine text (nass ilahi), and became something understandable, a human text (nass insani), because it changed from revelation to interpretation (li-annahu tahawwala min al-tanzil ila al-ta'wil). The Prophet's understanding of the text is one of the first phases of movement resulting from the text's connection with the human intellect.[37][38]

From the beginning of his academic career, Abu Zaid developed a renewed hermeneutic view (the theory and methodology of text interpretation) of the Qur'an and further Islamic holy texts, arguing that they should be interpreted in the historical and cultural context of their time. The mistake of many Muslim scholars was "to see the Qur'an only as a text, which led conservatives as well as liberals to a battle of quotations, each group seeing clear verses (when on their side) and ambiguous ones (when in contradiction with their vision)". But this type of controversy led both conservatives and liberals to produce authoritative hermeneutics. This vision of the Qur'an as a text was the vision of the elites of Muslim societies, whereas, at the same time, the Qur'an as "an oral discourse" played the most important part in the understanding of the masses.

Abu Zayd called for another reading of the holy book through a "humanistic hermeneutics", an interpretation which sees the Qur'an as a living phenomenon, a discourse. Hence, the Qur'an can be "the outcome of dialogue, debate, despite argument, acceptance and rejection". This liberal interpretation of Islam should open space for new perspectives on the religion and social change in Muslim societies. His analysis finds several "insistent calls for social justice" in the Qur'an . One example is when Muhammad—busy preaching to the rich people of Quraysh—failed to pay attention to a poor blind fellow named Ibn Umm Maktūm who came asking the Prophet for advice. The Quran strongly criticizes Muhammad's attitude. (Quran 80:10).[39]

Abu Zayd also argued that while the Qur'anic discourse was built in a patriarchal society, and therefore the addressees were naturally males, who received permission to marry, divorce, and marry off their female relatives, it is "possible to imagine that Muslim women receive the same rights", and so the Quran had a "tendency to improve women's rights". The classical position of the modern ‘ulamā’ about that issue is understandable as "they still believe in superiority of the male in the family".

Abu Zayd's critical approach to classical and contemporary Islamic discourse in the fields of theology, philosophy, law, politics, and humanism, promoted modern Islamic thought that might enable Muslims to build a bridge between their own tradition and the modern world of freedom of speech, equality (minority rights, women's rights, social justice), human rights, democracy and globalisation.[40]

Ibn Rushd was the preeminent philosopher in the history of Al-Andalus. 14th-century painting by Andrea di Bonaiuto

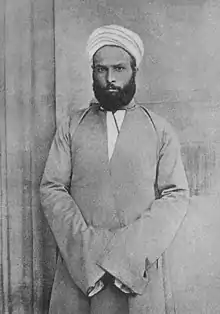

Ibn Rushd was the preeminent philosopher in the history of Al-Andalus. 14th-century painting by Andrea di Bonaiuto Rifa'a al-Tahtawy, 1801–1873.

Rifa'a al-Tahtawy, 1801–1873.

Ijtihad

Ijtihad (lit. effort, physical or mental, expended in a particular activity)[41] is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning[42] or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a legal question.[41] It is contrasted with taqlid (imitation, conformity to legal precedent).[42][43] According to classical Sunni theory, ijtihad requires expertise in the Arabic language, theology, revealed texts, and principles of jurisprudence (usul al-fiqh),[42] and is not employed where authentic and authoritative texts (Qur'an and hadith) are considered unambiguous with regard to the question, or where there is an existing scholarly consensus (ijma).[41] Ijtihad is considered to be a religious duty for those qualified to perform it.[42] An Islamic scholar who is qualified to perform ijtihad is called a mujtahid.[41]

Starting from the 18th century, some Muslim reformers began calling for abandonment of taqlid and emphasis on ijtihad, which they saw as a return to Islamic origins.[41] Public debates in the Muslim world surrounding ijtihad continue to the present day.[41] The advocacy of ijtihad has been particularly associated with Islamic modernists. Among contemporary Muslims in the West there have emerged new visions of ijtihad which emphasize substantive moral values over traditional juridical methodology.[41]

Specific issues

Feminism

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

A combination of Islam and feminism has been advocated as "a feminist discourse and practice articulated within an Islamic paradigm" by Margot Badran in 2002.[44] Islamic feminists ground their arguments in Islam and its teachings,[45] seek the full equality of women and men in the personal and public sphere, and can include non-Muslims in the discourse and debate. Islamic feminism is defined by Islamic scholars as being more radical than secular feminism,[46] and as being anchored within the discourse of Islam with the Quran as its central text.[47]

During recent times, the concept of Islamic feminism has grown further with Islamic groups looking to garner support from many aspects of society. In addition, educated Muslim women are striving to articulate their role in society.[48] Examples of Islamic feminist groups are the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan, founded by Meena Keshwar Kamal,[49] Muslim Women's Quest for Equality from India,[50][51] and Sisters in Islam from Malaysia, founded by Zainah Anwar and Amina Wadud among other five women.[52][53][54][55]

In 2014, the Selangor Islamic Religious Council (MAIS) issued a fatwa declaring that Sisters In Islam, as well as any other organisation promoting religious liberalism and pluralism, deviate from the teachings of Islam. According to the edict, publications that are deemed to promote liberal and pluralistic religious thinking are to be declared unlawful and confiscated, while social media is also to be monitored and restricted.[56] As fatwas are legally binding in Malaysia,[56] SIS is challenging it on constitutional grounds.[57]

Human rights

Moderate Islamic political thought contends that the nurturing of the Muslim identity and the propagation of values such as democracy and human rights are not mutually exclusive, but rather should be promoted together.[58]

Most liberal Muslims believe that Islam promotes the notion of absolute equality of all humanity, and that it is one of its central concepts. Therefore, a breach of human rights has become a source of great concern to most liberal Muslims.[59] Liberal Muslims differ with their culturally conservative counterparts in that they believe that all humanity is represented under the umbrella of human rights. Many Muslim majority countries have signed international human rights treaties, but the impact of these largely remains to be seen in local legal systems.

Muslim liberals often reject traditional interpretations of Islamic law, which allows Ma malakat aymanukum and slavery. They say that slavery opposed Islamic principles which they believe to be based on justice and equality and some say that verses relating to slavery or "Ma malakat aymanukum" now can not be applied due to the fact that the world has changed, while others say that those verses are totally misinterpreted and twisted to legitimize slavery.[60][61] In the 20th century, South Asian scholars Ghulam Ahmed Pervez and Amir Ali argued that the expression ma malakat aymanukum should be properly read in the past tense. When some called for reinstatement of slavery in Pakistan upon its independence from the British colonial rule, Pervez argued that the past tense of this expression means that the Quran had imposed "an unqualified ban" on slavery.[62]

Liberal Muslims have argued against death penalty for apostasy based on the Quranic verse that "There shall be no compulsion in religion."[63]

LGBT rights

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

|

In January 2013, the Muslim Alliance for Sexual and Gender Diversity (MASGD) was launched.[64] The organization was formed by members of the Queer Muslim Working Group, with the support of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Several initial MASGD members previously had been involved with the Al-Fatiha Foundation, including Faisal Alam and Imam Daayiee Abdullah.[65]

The Safra Project for women is based in the UK. It supports and works on issues relating to prejudice LGBTQ Muslim women. It was founded in October 2001 by Muslim LBT women. The Safra Project's “ethos is one of inclusiveness and diversity.”[66]

In Australia, Nur Wahrsage has been an advocate for LGBTI Muslims and founded Marhaba, a support group for queer Muslims in Melbourne, Australia. In May 2016, Wahrsage revealed that he is homosexual in an interview on SBS2’s The Feed, being the first openly gay Imam in Australia.[67]

In Canada, Salaam was founded as the first gay Muslim organization in Canada and the second in the world. Salaam was found in 1993 by El-Farouk Khaki, who organized the Salaam/Al-Fateha International Conference in 2003.[68]

In May 2009, the Toronto Unity Mosque / el-Tawhid Juma Circle was founded by Laury Silvers, a University of Toronto religious studies scholar, alongside Muslim gay-rights activists El-Farouk Khaki and Troy Jackson. Unity Mosque/ETJC is a gender-equal, LGBT+ affirming, mosque.[69][70][71][72]

In November 2012, a prayer room was set up in Paris, France by gay Islamic scholar and founder of the group 'Homosexual Muslims of France' Ludovic-Mohamed Zahed. It was described by the press as the first gay-friendly mosque in Europe. The reaction from the rest of the Muslim community in France has been mixed, the opening has been condemned by the Grand Mosque of Paris.[73]

Examples of Muslim LGBT media works are the 2006 Channel 4's documentary Gay Muslims,[74] the film production company Unity Productions Foundation,[75] the 2007 and 2015 documentary films A Jihad for Love and A Sinner in Mecca, both produced by Parvez Sharma,[76][77][78] and the Jordanian LGBT publication My.Kali.[79][80]

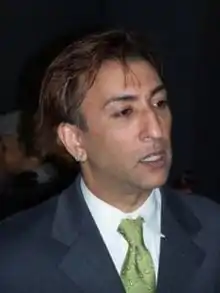

El-Farouk Khaki, founding member of Salaam group and the Toronto Unity Mosque / el-Tawhid Juma Circle

El-Farouk Khaki, founding member of Salaam group and the Toronto Unity Mosque / el-Tawhid Juma Circle

Secularism

The definition and application of secularism, especially the place of religion in society, varies among Muslim countries as it does among non-Muslim countries.[81] As the concept of secularism varies among secularists in the Muslim world, reactions of Muslim intellectuals to the pressure of secularization also varies. On the one hand, secularism is condemned by some Muslim intellectuals who do not feel that religious influence should be removed from the public sphere.[82] On the other hand, secularism is claimed by others to be compatible with Islam. For example, the quest for secularism has inspired some Muslim scholars who argue that secular government is the best way to observe sharia; "enforcing [sharia] through coercive power of the state negates its religious nature, because Muslims would be observing the law of the state and not freely performing their religious obligation as Muslims" says Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im, a professor of law at Emory University and author of Islam and the secular state : negotiating the future of Shariʻa.[83] Moreover, some scholars argue that secular states have existed in the Muslim world since the Middle Ages.[84]

Sayyid supremacism and caste system in Islam

Sayyids have special privileges in Islam, notably of tax exemptions and a share in Khums.[85] Discrimination also exists in regards of intermarriage between persons of Arab and non-Arab lineages with the following ruling being relevant according to Hanafi school:

The Jurists have stated that among Arabs, a non-Quraishi male is not a match (Kuf) for a Quraishi woman, nor can any person of non-Arab descent be a match for a woman of Arab descent. For example, the Sayyids, whether Siddique or Farooque, Uthmaani or Alawi, or belonging to some other branch can never be matched by any person not sharing their lineage, no matter his profession and family status. The Sayyids are suitable matches for one another, since they share descent from the Quraishi tribe. Thus, marriages between themselves are correct and permitted without any condition as appearing in Durrul Mukhtar:

“And Kafaah in lineage. Thus the Quraysh are suitable matches for one another as are the (other) Arabs suitable matches for one another.”

The ruling relevant to non-Arabs is as follows: ‘An Ajmi (non-Arab) cannot be a match for a woman of Arab descent, no matter that he be an Aalim (religious scholar) or even a Sultan (ruling authority). (Raddul Muhtar p.209 v.4)[86]

However, such marriages are legally recognised in Sharia and above mentioned text is a recommendation."Islam QA". Darul Ifta Birmingham. 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2020-07-14.</ref>

South Asian Muslims have a complex system of castes heavily influenced by Hindu caste system but scholars have opined that Islamic influence had an independent contribution to it.[87]

Movements

Over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, in accordance with their increasingly modern societies and outlooks, liberal Muslims have tended to reinterpret many aspects of the application of their religion in their life in an attempt to reconnect. This is particularly true of Muslims who now find themselves living in non-Muslim countries.[88]

At least one observer (Max Rodenbeck) has noted several challenges to "reform"—i.e. accommodation with the enlightenment, reason and science, the separation of religion and politics—that the other two Abrahamic faiths did not have to grapple with:

whereas Christian and Jewish reform evolved over centuries, in relatively organic and self-generated—albeit often bloody—fashion, the challenge to Islam of such concepts as empirical reasoning, the nation-state, the theory of evolution, and individualism arrived all in a heap and all too often at the point of a gun.[89]

In addition, traditional sharia law has been shaped in all its complexity by serving for centuries as "the backbone" of legal systems of Muslim states, while millions of Muslim now live in non-Muslim states. Islam also lacks a "widely recognized religious hierarchy to explain doctrinal changes or to enforce them" because it has no [central] church.[89]

Islamic Modernism

Islamic Modernism, also sometimes referred to as Modernist Salafism,[90][91][92] is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response"[lower-alpha 1] attempting to reconcile Islamic faith with modern Western values such as nationalism, democracy, civil rights, rationality, equality, and progress.[94] It featured a "critical reexamination of the classical conceptions and methods of jurisprudence" and a new approach to Islamic theology and Quranic exegesis (Tafsir).[93]

It was the first of several Islamic movements – including secularism, Islamism and Salafism – that emerged in the middle of the 19th century in reaction to the rapid changes of the time, especially the perceived onslaught of Western Civilization and colonialism on the Muslim world.[94] Founders include Muhammad Abduh, a Sheikh of Al-Azhar University for a brief period before his death in 1905, Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, and Muhammad Rashid Rida (d. 1935).

The early Islamic Modernists (al-Afghani and Muhammad Abdu) used the term "salafiyya"[95] to refer to their attempt at renovation of Islamic thought,[96] and this "salafiyya movement" is often known in the West as "Islamic modernism," although it is very different from what is currently called the Salafi movement, which generally signifies "ideologies such as wahhabism".[lower-alpha 2] Since its inception, Modernism has suffered from co-option of its original reformism by both secularist rulers and by "the official ulama" whose "task it is to legitimise" rulers' actions in religious terms.[97]

Modernism differs from secularism in that it insists on the importance of religious faith in public life, and from Salafism or Islamism in that it embraces contemporary European institutions, social processes, and values.[94]

Quranism

Quranists believe Muhammad himself was a Quranist and the founder of Quranism, and that his followers distorted the faith and split into schisms and factions such as Sunni, Shia, and Khawarij. Quranists reject the hadith and follow the Quran only. The extent to which Quranists reject the authenticity of the Sunnah varies,[98] but the more established groups have thoroughly criticised the authenticity of the hadith and refused it for many reasons, the most prevalent being the Quranist claim that hadith is not mentioned in the Quran as a source of Islamic theology and practice, was not recorded in written form until more than two centuries after the death of the Muhammed, and contain perceived internal errors and contradictions.[98][99]

Tolu-e-Islam

The movement was initiated by Muhammad Iqbal, and later spearheaded by Ghulam Ahmed Pervez. Ghulam Ahmed Pervez did not reject all hadiths; however, he only accepted hadiths which "are in accordance with the Quran or do not stain the character of the Prophet or his companions".[100] The organization publishes and distributes books, pamphlets, and recordings of Pervez's teachings.[100]

Tolu-e-Islam does not belong to any political party, nor does it belong to any religious group or sect.

See also

Notes

- "Islamic modernism was the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge. Started in India and Egypt in the second part of the 19th century ... reflected in the work of a group of like-minded Muslim scholars, featuring a critical reexamination of the classical conceptions and methods of jurisprudence and a formulation of a new approach to Islamic theology and Quranic exegesis. This new approach, which was nothing short of an outright rebellion against Islamic orthodoxy, displayed astonishing compatibility with the ideas of the Enlightenment."[93]

- "Salafism is, therefore, a modern phenomenon, being the desire of contemporary Muslims to rediscover what they see as the pure, original and authentic Islam, ... However, there is a difference between two profoundly different trends which sought inspiration from the concept of salafiyya. Indeed, between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of 20th century, intellectuals such as Jamal Edin al-Afghani and Muhammad Abdu used salafiyya to mean a renovation of Islamic thought, with features that would today be described as rationalist, modernist and even progressive. This salafiyya movement is often known in the West as “Islamic modernism.‘ However, the term salafism is today generally employed to signify ideologies such as Wahhabism, the puritanical ideology of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia."[96]

References

- Safi, Omid, ed. (2003). Progressive Muslims: on justice, gender and pluralism. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781851683161. OCLC 52380025.

- Safi, Omid. "What is Progressive Islam?". averroes-foundation.org. Averroes Foundation. Archived from the original on July 9, 2006.

- "Liberalism - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- Aslan, Reza (2011) [2005]. No god but God: the origins, evolution, and future of Islam (Updated ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 9780812982442. OCLC 720168240.

- Sajid, Abdul Jalil (December 10, 2001). "'Islam against Religious Extremism and Fanaticism': speech delivered by Imam Abdul Jalil Sajid at a meeting on International NGO Rights and Humanity". mcb.org.uk. Muslim Council of Britain. Archived from the original on June 7, 2008.

- "Tawhid". oxfordislamicstudies.com. Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Zubaidah Rahim, Lily (2006). "Discursive Contest between Liberal and Literal Islam in Southeast Asia". Policy and Society. 25 (4): 77–98. doi:10.1016/S1449-4035(06)70091-1. S2CID 218567875.

- Aslan, Reza (2005). No god but God. Random House Inc. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-58836-445-6.

By the ninth and tenth centuries...

- "John Carter Brown Library Exhibitions – Islamic encounters". Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- "Ahmed, K. S. "Arabic Medicine: Contributions and Influence". The Proceedings of the 17th Annual History of Medicine Days, March 7th and 8th, 2008 Health Sciences Centre, Calgary, AB" (PDF). Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- Sarrió, Diego R. (2015). "The Philosopher as the Heir of the Prophets: Averroes's Islamic Rationalism". Al-Qanṭara. 36 (1): 45–68. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2015.002. ISSN 1988-2955. p.48

- Abdel Wahab El Messeri. Episode 21: Ibn Rushd, Everything you wanted to know about Islam but was afraid to Ask, Philosophia Islamica.

- Fauzi M. Najjar (Spring, 1996). The debate on Islam and secularism in Egypt Archived 2010-04-04 at the Wayback Machine, Arab Studies Quarterly (ASQ).

- Averroes (2005). Averroes On Plato's Republic. Translated by Ralph Lerner. Cornell University Press. p. xix. ISBN 0-8014-8975-X.

- Fakhry, Majid (2001). Averroes (Ibn Rushd) His Life, Works and Influence. Oneworld Publications. p. 110. ISBN 1-85168-269-4.

- Nicola Missaglia, "Mohamed Abed Al-Jabri's new Averroism"

- Vatikiotis, P. J. (1976). The Modern History of Egypt (Repr. ed.). ISBN 978-0297772620. p. 115-16

- Vatikiotis, P. J. (1976). The Modern History of Egypt (Repr. ed.). ISBN 978-0297772620. p. 116

- Gelvin, 133-134

- Cleveland, William L. (2008)"History of the Modern Middle East" (4th ed.) pg.93.

- Galvin 160-161

- Ahmed H. Al-Rahim (January 2006). "Islam and Liberty", Journal of Democracy 17 (1), p. 166-169.

- Kerr, Malcolm H. (2010). "'Abduh Muhammad". In Hoiberg, Dale H. (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Gelvin, J. L. (2008). The Modern Middle East (2nd ed., pp. 161-162). New York: Oxford university Press.

- Kügelgen, Anke von. "ʿAbduh, Muḥammad." Encyclopaedia of Islam, v. 3. Edited by: Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas and Everett Rowson. Brill, 2009. Syracuse University. 23 April 2009

- ʿAbduh, Muhammad. "al-Idtihad fi al-Nasraniyya wa al-Islam." In al-A'mal al-Kamila li al-Imam Muhammad ʿAbduh. edited by Muhammad ʿAmara. Cairo: Dar al-Shuruk, 1993. 257-368.

- Hourani, Albert. Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age 1798-1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. 156.

- Benzine, Rachid. Les nouveaux penseurs de l'islam, p. 43-44.

- "Naṣr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- Cook, Michael (2000). The Koran : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 0192853449.

- Kermani, "From revelation to interpretation", 2004: p.174

- "Nasr Abu Zayd, Who Stirred Debate on Koran, Dies at 66". REUTERS. 6 July 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- Mafhum al-nass: dirasa fi 'ulum al-Qur'an. Cairo, 1990. , p.11

- Shepard, William E. "Abu Zayd, Nasir Hamid". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Kermani, "From revelation to interpretation", 2004: p.173

- Kermani, "From revelation to interpretation", 2004: p.171

- Kermani, "From revelation to interpretation", 2004: p.172

- Naqd al-hhitab al-dini, p. 93., translated by Kermani, Navid (2004). "From revelation to interpretation: Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd and the Literary study of the Qur'an" (PDF). In Taji-Farouki, Suha (ed.). Modern Muslim Intellectuals and the Qur'an. Oxford University Press. p. 172.

- (Quran 80:10)

- "10. Reformers. Reformers in the Modern Period". Faith and Philosophy of Islam. Gyan Publishing House. 2009. pp. 166–7. ISBN 978-81-7835-719-5.

- Rabb, Intisar A. (2009). "Ijtihād". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- John L. Esposito, ed. (2014). "Ijtihad". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- John L. Esposito, ed. (2014). "Taqlid". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Al-Ahram Weekly | Culture | Islamic feminism: what's in a name? Archived March 20, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "'Islamic feminism means justice to women', The Milli Gazette, Vol.5 No.02, MG96 (16-31 January 04)". milligazette.com. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Islamic feminism: what's in a name?" Archived 2015-03-20 at the Wayback Machine by Margot Badran, Al-Ahram, January 17–23, 2002

- "Exploring Islamic Feminism" Archived 2005-04-16 at the Wayback Machine by Margot Badran, Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, Georgetown University, November 30, 2000

- Rob L. Wagner: "Saudi-Islamic Feminist Movement: A Struggle for Male Allies and the Right Female Voice", University for Peace (Peace and Conflict Monitor), March 29, 2011

- "RAWA testimony to the Congressional Human Rights Caucus Briefing". U.S. Congressional Human Rights Caucus. December 18, 2001. Archived from the original on June 28, 2007.

- "Muslim women's group demands complete ban on Shariah courts | india-news". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- "SC admits Muslim woman's plea to declare triple talaq illegal". The Hindu. 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- "Polygamy not a God-given right to Muslims".

- "Syariah court fails to protect and safeguard Muslim girls — Sisters in Islam". Archived from the original on 2014-07-14.

- "Archives".

- "Sisters In Islam: News / Comments / Dress and Modesty in Islam".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2014-11-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Sisters in Islam files for judicial review on fatwa - Nation - The Star Online". www.thestar.com.my.

- The Fundamentalist City?: Religiosity and the Remaking of Urban Space, Nezar Alsayyad (ed.), Chapter 7: "Hamas in Gaza Refugee camps: The Construction of Trapped Spaces for the Survival of Fundamentalism", Francesca Giovannini. Taylor & Francis, 2010. ISBN 978-0-415-77936-4."

- Hassan Mahmoud Khalil: "Islam's position on violence and violation of human rights", Dar Al-Shaeb, 1994.

- "Writer and Islamic thinker "Gamal al-Banna": The Muslim Brotherhood is not fit to rule (2-2)". Ahewar.org. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- "Writer and Islamic thinker "Gamal al-Banna": The Muslim Brotherhood is not fit to rule (1-2)". Ahewar.org. 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- Clarence-Smith, William (2006). Islam and the Abolition of Slavery. Oxford University Press. pp. 198–200. ISBN 0195221516.

- "Sudan death penalty reignites Islam apostasy debate". BBC News. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "Muslim Alliance for Sexual and Gender Diversity". Muslimalliance.org. Retrieved 2013-11-18.

- "The Progressive Muslim Movement". OutSmart Magazine. October 1, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- "The Safra Project - rabble.ca". Rabble.ca. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- Power, Shannon (3 May 2016). "Being gay and muslim: 'death is your repentance'". Star Observer. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Catherine Patch, "Queer Muslims find peace; El-Farouk Khaki founded Salaam Offers a place to retain spirituality", Toronto Star, June 15, 2006

- "El-tawhid juma circle". Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Mastracci, Davide (April 4, 2017). "What It's Like To Pray At A Queer-Inclusive Mosque". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Habib, Samra (3 June 2016). "Queer and going to the mosque: 'I've never felt more Muslim than I do now'". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Gillis, Wendy (August 25, 2013). "Islamic scholars experience diversity of Muslim practices at U of T summer program". Toronto Star. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Banerji, Robin (30 November 2012). "Gay-friendly 'mosque' opens in Paris". BBC News.

- "Channel 4 in a Nutshell" (PDF).

- "About UPF - UPF (Unity Productions Foundation)". UPF.tv. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "A JIHAD FOR LOVE:::A FIlm by Parvez Sharma". AJihadForLove.org. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "Press". A Sinner in Mecca. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "In 'A Sinner in Mecca,' a Gay Director Ponders His Sexuality and Islamic Faith". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- "Jordan: a gay magazine gives an hope to Middle East", Ilgrandecolibri.com, retrieved 11 August 2012

- "Gay Egypy". Gay Middle East. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- Asad, Talal. Formation of Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003. 5-6.

- "From the article on secularism in Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- Naʻīm, ʻAbd Allāh Aḥmad. Islam and the secular state : negotiating the future of Shariʻa. Cambridge:Harvard University Press, 2008. ISBN 9780674027763

- Ira M. Lapidus (October 1975). "The Separation of State and Religion in the Development of Early Islamic Society", International Journal of Middle East Studies 6 (4), pp. 363-385 [364-5]

- Kazuo, Morimoto (2012). Sayyids and Sharifs in Muslim Societies. Routledge. pp. 131, 132. ISBN 978-0-415-51917-5.

- "Islam QA". Darul Ifta Birmingham. 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- "Is Islamic caste system entirely a Hindu influence?". Round Table India. 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- Being a Muslim in the U.S.ا Archived January 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Rodenbeck, Max (3 December 2015). "How She Wants to Modify Muslims [Review of Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now by Ayaan Hirsi Ali]". New York Review of Books. LXII (19): 36. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Salafism Modernist Salafism from the 20th Century to the Present

- Tore Kjeilen (2006-01-18). "Salafism". I-cias.com. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- Salafism Archived 2015-03-11 at the Wayback Machine Tony Blair Faith Foundation

- Mansoor Moaddel (2005-05-16). Islamic Modernism, Nationalism, and Fundamentalism: Episode and Discourse. University of Chicago Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780226533339.

- Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World, Thompson Gale (2004)

- Salafism, Modernist Salafism from the 20th Century to the Present oxfordbibliographies.com

- Atzori, Daniel (August 31, 2012). "The rise of global Salafism". Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Ruthven, Malise (2006) [1984]. Islam in the World. Oxford University Press. p. 318. ISBN 9780195305036. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Richard Stephen Voss, Identifying Assumptions in the Hadith/Sunnah Debate, 19.org, Accessed December 5, 2013

- Aisha Y. Musa, The Qur’anists, Florida International University, accessed May 22, 2013.

- "Bazm-e-Tolu-e-Islam". Retrieved 22 March 2015.

Further reading

- Safi, Omid, Progressive Islam, in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol. II, pp. 486–490. ISBN 1610691776

- Qur'an and Woman by Amina Wadud.

- American Muslims: Bridging Faith and Freedom by M. A. Muqtedar Khan.

- Charles Kurzman, ed. (1998). Liberal Islam: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-511622-4.

- Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism, edited by Omid Safi.

- "Debating Moderate Islam", edited by M. A. Muqtedar Khan.

- Qur'an, Liberation and Pluralism by Farid Esack.

- Revival and Reform in Islam by Fazlur Rahman Malik.

- The Unthought in Contemporary Islamic Thought by Mohammed Arkoun.

- Unveiling Traditions: Postcolonial Islam in a Polycentric World by Anouar Majid.

- Islam and Science: Religious Orthodoxy and the Battle for Rationality by Pervez Hoodbhoy.

- Islam is Mercy: Essential Features of a Modern Religion, by Mouhanad Khorchide 2012; English 2014.

- The Viability of Islamic Science by S. Irfan Habib, Economic and Political Weekly, June 5, 2004.

- The Reformist Islamic Thinker Muhammad Shahrur: In the Footsteps of Averroes

- A Liberal Muslim Blog

- Vanessa Karam, Olivia Samad and Ani Zonneveld, eds. (2011). Progressive Muslim Identities. Oracle Releasing. ISBN 978-0-9837161-0-5.

- Mustafa Akyol (2011). Islam Without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-07086-6.

- Alrabaa, Sami (2010). Veiled Atrocities: True Stories of Oppression in Saudi Arabia. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-61614-159-2.

- Al-Rasheed, Madawi (2007). Contesting the Saudi State: Islamic Voices from a New Generation. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85836-6.

External links

- Charles Kurzman's Liberal Islam links, compiled by the author of Liberal Islam: A Sourcebook.