Muon

The muon (/ˈmjuːɒn/; from the Greek letter mu (μ) used to represent it) is an elementary particle similar to the electron, with an electric charge of −1 e and a spin of 1/2, but with a much greater mass. It is classified as a lepton. As with other leptons, the muon is not known to have any sub-structure – that is, it is not thought to be composed of any simpler particles.

The Moon's cosmic ray shadow, as seen in secondary muons generated by cosmic rays in the atmosphere, and detected 700 meters below ground, at the Soudan II detector | |

| Composition | Elementary particle |

|---|---|

| Statistics | Fermionic |

| Generation | Second |

| Interactions | Gravity, Electromagnetic, Weak |

| Symbol | μ− |

| Antiparticle | Antimuon ( μ+ ) |

| Discovered | Carl D. Anderson, Seth Neddermeyer (1936) |

| Mass | 1.883531627(42)×10−28 kg[1] 0.1134289259(25) Da[1] |

| Mean lifetime | 2.1969811(22)×10−6 s[2][3] |

| Decays into | e− , ν e, ν μ[3] (most common) |

| Electric charge | −1 e |

| Color charge | None |

| Spin | 1/2 |

| Weak isospin | LH: −1/2, RH: 0 |

| Weak hypercharge | LH: −1, RH: −2 |

The muon is an unstable subatomic particle with a mean lifetime of 2.2 μs, much longer than many other subatomic particles. As with the decay of the non-elementary neutron (with a lifetime around 15 minutes), muon decay is slow (by subatomic standards) because the decay is mediated only by the weak interaction (rather than the more powerful strong interaction or electromagnetic interaction), and because the mass difference between the muon and the set of its decay products is small, providing few kinetic degrees of freedom for decay. Muon decay almost always produces at least three particles, which must include an electron of the same charge as the muon and two types of neutrinos.

Like all elementary particles, the muon has a corresponding antiparticle of opposite charge (+1 e) but equal mass and spin: the antimuon (also called a positive muon). Muons are denoted by

μ−

and antimuons by

μ+

. Muons were formerly called "mu mesons", but are not classified as mesons by modern particle physicists (see § History), and that name is no longer used by the physics community.

Muons have a mass of 105.66 MeV/c2, which is about 207 times that of the electron, . More precisely, it is 206.768 2830(46) .[1]

Due to their greater mass, muons accelerate more slowly than electrons in electromagnetic fields, and emit less bremsstrahlung (deceleration radiation). This allows muons of a given energy to penetrate far deeper into matter because the deceleration of electrons and muons is primarily due to energy loss by the bremsstrahlung mechanism. For example, so-called "secondary muons", created by cosmic rays hitting the atmosphere, can penetrate the atmosphere and reach Earth's land surface and even into deep mines.

Because muons have a greater mass and energy than the decay energy of radioactivity, they are not produced by radioactive decay. However they are produced in great amounts in high-energy interactions in normal matter, in certain particle accelerator experiments with hadrons, and in cosmic ray interactions with matter. These interactions usually produce pi mesons initially, which almost always decay to muons.

As with the other charged leptons, the muon has an associated muon neutrino, denoted by

ν

μ, which differs from the electron neutrino and participates in different nuclear reactions.

History

Muons were discovered by Carl D. Anderson and Seth Neddermeyer at Caltech in 1936, while studying cosmic radiation. Anderson noticed particles that curved differently from electrons and other known particles when passed through a magnetic field. They were negatively charged but curved less sharply than electrons, but more sharply than protons, for particles of the same velocity. It was assumed that the magnitude of their negative electric charge was equal to that of the electron, and so to account for the difference in curvature, it was supposed that their mass was greater than an electron but smaller than a proton. Thus Anderson initially called the new particle a mesotron, adopting the prefix meso- from the Greek word for "mid-". The existence of the muon was confirmed in 1937 by J.C. Street and E.C. Stevenson's cloud chamber experiment.[4]

A particle with a mass in the meson range had been predicted before the discovery of any mesons, by theorist Hideki Yukawa:[5]

It seems natural to modify the theory of Heisenberg and Fermi in the following way. The transition of a heavy particle from neutron state to proton state is not always accompanied by the emission of light particles. The transition is sometimes taken up by another heavy particle.

Because of its mass, the mu meson was initially thought to be Yukawa's particle, but it later proved to have the wrong properties. Some scientists, including Niels Bohr, initially named it Yukon because of this. Yukawa's predicted particle, the pi meson, was finally identified in 1947 (again from cosmic ray interactions), and shown to differ from the earlier-discovered mu meson by having the correct properties to be a particle which mediated the nuclear force.

With two particles now known with the intermediate mass, the more general term meson was adopted to refer to any such particle within the correct mass range between electrons and nucleons. Further, in order to differentiate between the two different types of mesons after the second meson was discovered, the initial mesotron particle was renamed the mu meson (the Greek letter μ [mu] corresponds to m), and the new 1947 meson (Yukawa's particle) was named the pi meson.

As more types of mesons were discovered in accelerator experiments later, it was eventually found that the mu meson significantly differed not only from the pi meson (of about the same mass), but also from all other types of mesons. The difference, in part, was that mu mesons did not interact with the nuclear force, as pi mesons did (and were required to do, in Yukawa's theory). Newer mesons also showed evidence of behaving like the pi meson in nuclear interactions, but not like the mu meson. Also, the mu meson's decay products included both a neutrino and an antineutrino, rather than just one or the other, as was observed in the decay of other charged mesons.

In the eventual Standard Model of particle physics codified in the 1970s, all mesons other than the mu meson were understood to be hadrons – that is, particles made of quarks – and thus subject to the nuclear force. In the quark model, a meson was no longer defined by mass (for some had been discovered that were very massive – more than nucleons), but instead were particles composed of exactly two quarks (a quark and antiquark), unlike the baryons, which are defined as particles composed of three quarks (protons and neutrons were the lightest baryons). Mu mesons, however, had shown themselves to be fundamental particles (leptons) like electrons, with no quark structure. Thus, mu "mesons" were not mesons at all, in the new sense and use of the term meson used with the quark model of particle structure.

With this change in definition, the term mu meson was abandoned, and replaced whenever possible with the modern term muon, making the term "mu meson" only a historical footnote. In the new quark model, other types of mesons sometimes continued to be referred to in shorter terminology (e.g., pion for pi meson), but in the case of the muon, it retained the shorter name and was never again properly referred to by older "mu meson" terminology.

The eventual recognition of the muon as a simple "heavy electron", with no role at all in the nuclear interaction, seemed so incongruous and surprising at the time, that Nobel laureate I. I. Rabi famously quipped, "Who ordered that?"[6]

In the Rossi–Hall experiment (1941), muons were used to observe the time dilation (or, alternatively, length contraction) predicted by special relativity, for the first time.

Muon sources

Muons arriving on the Earth's surface are created indirectly as decay products of collisions of cosmic rays with particles of the Earth's atmosphere.[7]

About 10,000 muons reach every square meter of the earth's surface a minute; these charged particles form as by-products of cosmic rays colliding with molecules in the upper atmosphere. Traveling at relativistic speeds, muons can penetrate tens of meters into rocks and other matter before attenuating as a result of absorption or deflection by other atoms.[8]

When a cosmic ray proton impacts atomic nuclei in the upper atmosphere, pions are created. These decay within a relatively short distance (meters) into muons (their preferred decay product), and muon neutrinos. The muons from these high-energy cosmic rays generally continue in about the same direction as the original proton, at a velocity near the speed of light. Although their lifetime without relativistic effects would allow a half-survival distance of only about 456 meters ( 2.197 µs × ln(2) × 0.9997 × c ) at most (as seen from Earth) the time dilation effect of special relativity (from the viewpoint of the Earth) allows cosmic ray secondary muons to survive the flight to the Earth's surface, since in the Earth frame the muons have a longer half-life due to their velocity. From the viewpoint (inertial frame) of the muon, on the other hand, it is the length contraction effect of special relativity which allows this penetration, since in the muon frame its lifetime is unaffected, but the length contraction causes distances through the atmosphere and Earth to be far shorter than these distances in the Earth rest-frame. Both effects are equally valid ways of explaining the fast muon's unusual survival over distances.

Since muons are unusually penetrative of ordinary matter, like neutrinos, they are also detectable deep underground (700 meters at the Soudan 2 detector) and underwater, where they form a major part of the natural background ionizing radiation. Like cosmic rays, as noted, this secondary muon radiation is also directional.

The same nuclear reaction described above (i.e. hadron-hadron impacts to produce pion beams, which then quickly decay to muon beams over short distances) is used by particle physicists to produce muon beams, such as the beam used for the muon g−2 experiment.[9]

Muon decay

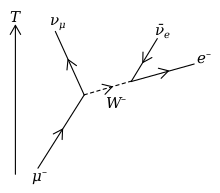

Muons are unstable elementary particles and are heavier than electrons and neutrinos but lighter than all other matter particles. They decay via the weak interaction. Because leptonic family numbers are conserved in the absence of an extremely unlikely immediate neutrino oscillation, one of the product neutrinos of muon decay must be a muon-type neutrino and the other an electron-type antineutrino (antimuon decay produces the corresponding antiparticles, as detailed below).

Because charge must be conserved, one of the products of muon decay is always an electron of the same charge as the muon (a positron if it is a positive muon). Thus all muons decay to at least an electron, and two neutrinos. Sometimes, besides these necessary products, additional other particles that have no net charge and spin of zero (e.g., a pair of photons, or an electron-positron pair), are produced.

The dominant muon decay mode (sometimes called the Michel decay after Louis Michel) is the simplest possible: the muon decays to an electron, an electron antineutrino, and a muon neutrino. Antimuons, in mirror fashion, most often decay to the corresponding antiparticles: a positron, an electron neutrino, and a muon antineutrino. In formulaic terms, these two decays are:

The mean lifetime, τ = ħ/Γ, of the (positive) muon is (2.1969811±0.0000022) μs.[2] The equality of the muon and antimuon lifetimes has been established to better than one part in 104.

Prohibited decays

Certain neutrino-less decay modes are kinematically allowed but are, for all practical purposes, forbidden in the Standard Model, even given that neutrinos have mass and oscillate. Examples forbidden by lepton flavour conservation are:

μ−

→

e−

+

γ

and

μ−

→

e−

+

e+

+

e−

.

To be precise: in the Standard Model with neutrino mass, a decay like

μ−

→

e−

+

γ

is technically possible, for example by neutrino oscillation of a virtual muon neutrino into an electron neutrino, but such a decay is astronomically unlikely and therefore should be experimentally unobservable: Less than one in 1050 muon decays should produce such a decay.

Observation of such decay modes would constitute clear evidence for theories beyond the Standard Model. Upper limits for the branching fractions of such decay modes were measured in many experiments starting more than 50 years ago. The current upper limit for the

μ+

→

e+

+

γ

branching fraction was measured 2009–2013 in the MEG experiment and is 4.2 × 10−13.[10]

Theoretical decay rate

The muon decay width which follows from Fermi's golden rule has dimension of energy, and must be proportional to the square of the amplitude, and thus the square of Fermi's coupling constant (), with over-all dimension of inverse fourth power of energy. By dimensional analysis, this leads to Sargent's rule of fifth-power dependence on mμ ,

where , and

- is the fraction of the maximum energy transmitted to the electron.

The decay distributions of the electron in muon decays have been parameterised using the so-called Michel parameters. The values of these four parameters are predicted unambiguously in the Standard Model of particle physics, thus muon decays represent a good test of the space-time structure of the weak interaction. No deviation from the Standard Model predictions has yet been found.

For the decay of the muon, the expected decay distribution for the Standard Model values of Michel parameters is

where is the angle between the muon's polarization vector and the decay-electron momentum vector, and is the fraction of muons that are forward-polarized. Integrating this expression over electron energy gives the angular distribution of the daughter electrons:

The electron energy distribution integrated over the polar angle (valid for ) is

Due to the muons decaying by the weak interaction, parity conservation is violated. Replacing the term in the expected decay values of the Michel Parameters with a term, where ω is the Larmor frequency from Larmor precession of the muon in a uniform magnetic field, given by:

where m is mass of the muon, e is charge, g is the muon g-factor and B is applied field.

A change in the electron distribution computed using the standard, unprecessional, Michel Parameters can be seen displaying a periodicity of π radians. This can be shown to physically correspond to a phase change of π, introduced in the electron distribution as the angular momentum is changed by the action of the charge conjugation operator, which is conserved by the weak interaction.

The observation of parity violation in muon decay can be compared to the concept of violation of parity in weak interactions in general as an extension of the Wu experiment, as well as the change of angular momentum introduced by a phase change of π corresponding to the charge-parity operator being invariant in this interaction. This fact is true for all lepton interactions in The Standard Model.

Muonic atoms

The muon was the first elementary particle discovered that does not appear in ordinary atoms.

Negative muon atoms

Negative muons can, however, form muonic atoms (previously called mu-mesic atoms), by replacing an electron in ordinary atoms. Muonic hydrogen atoms are much smaller than typical hydrogen atoms because the much larger mass of the muon gives it a much more localized ground-state wavefunction than is observed for the electron. In multi-electron atoms, when only one of the electrons is replaced by a muon, the size of the atom continues to be determined by the other electrons, and the atomic size is nearly unchanged. However, in such cases the orbital of the muon continues to be smaller and far closer to the nucleus than the atomic orbitals of the electrons.

Muonic helium is created by substituting a muon for one of the electrons in helium-4. The muon orbits much closer to the nucleus, so muonic helium can therefore be regarded like an isotope of helium whose nucleus consists of two neutrons, two protons and a muon, with a single electron outside. Colloquially, it could be called "helium 4.1", since the mass of the muon is slightly greater than 0.1 amu. Chemically, muonic helium, possessing an unpaired valence electron, can bond with other atoms, and behaves more like a hydrogen atom than an inert helium atom.[11][12][13]

Muonic heavy hydrogen atoms with a negative muon may undergo nuclear fusion in the process of muon-catalyzed fusion, after the muon may leave the new atom to induce fusion in another hydrogen molecule. This process continues until the negative muon is captured by a helium nucleus, and cannot escape until it decays.

Negative muons bound to conventional atoms can be captured (muon capture) through the weak force by protons in nuclei, in a sort of electron-capture-like process. When this happens, nuclear transmutation results: The proton becomes a neutron and a muon neutrino is emitted.

Positive muon atoms

A positive muon, when stopped in ordinary matter, cannot be captured by a proton since the two positive charges can only repel. The positive muon is also not attracted to the nucleus of atoms. Instead, it binds a random electron and with this electron forms an exotic atom known as muonium (mu) atom. In this atom, the muon acts as the nucleus. The positive muon, in this context, can be considered a pseudo-isotope of hydrogen with one ninth of the mass of the proton. Because the mass of the electron is much smaller than the mass of both the proton and the muon, the reduced mass of muonium, and hence its Bohr radius, is very close to that of hydrogen. Therefore this bound muon-electron pair can be treated to a first approximation as a short-lived "atom" that behaves chemically like the isotopes of hydrogen (protium, deuterium and tritium).

Both positive and negative muons can be part of a short-lived pi-mu atom consisting of a muon and an oppositely charged pion. These atoms were observed in the 1970s in experiments at Brookhaven and Fermilab.[14][15]

Use in measurement of the proton charge radius

| Unsolved problem in physics: What is the true charge radius of the proton? (more unsolved problems in physics) |

The experimental technique that is expected to provide the most precise determination of the root-mean-square charge radius of the proton is the measurement of the frequency of photons (precise "color" of light) emitted or absorbed by atomic transitions in muonic hydrogen. This form of hydrogen atom is composed of a negatively charged muon bound to a proton. The muon is particularly well suited for this purpose because its much larger mass results in a much more compact bound state and hence a larger probability for it to be found inside the proton in muonic hydrogen compared to the electron in atomic hydrogen.[16] The Lamb shift in muonic hydrogen was measured by driving the muon from a 2s state up to an excited 2p state using a laser. The frequency of the photons required to induce two such (slightly different) transitions were reported in 2014 to be 50 and 55 THz which, according to present theories of quantum electrodynamics, yield an appropriately averaged value of 0.84087±0.00039 fm for the charge radius of the proton.[17]

The internationally accepted value of the proton's charge radius is based on a suitable average of results from older measurements of effects caused by the nonzero size of the proton on scattering of electrons by nuclei and the light spectrum (photon energies) from excited atomic hydrogen. The official value updated in 2014 is 0.8751±0.0061 fm (see orders of magnitude for comparison to other sizes).[18] The expected precision of this result is inferior to that from muonic hydrogen by about a factor of fifteen, yet they disagree by about 5.6 times the nominal uncertainty in the difference (a discrepancy called 5.6 σ in scientific notation). A conference of the world experts on this topic led to the decision to exclude the muon result from influencing the official 2014 value, in order to avoid hiding the mysterious discrepancy.[19] This "proton radius puzzle" remained unresolved as of late 2015, and has attracted much attention, in part because of the possibility that both measurements are valid, which would imply the influence of some "new physics".[20]

Anomalous magnetic dipole moment

The anomalous magnetic dipole moment is the difference between the experimentally observed value of the magnetic dipole moment and the theoretical value predicted by the Dirac equation. The measurement and prediction of this value is very important in the precision tests of QED (quantum electrodynamics). The E821 experiment[21] at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) studied the precession of muon and anti-muon in a constant external magnetic field as they circulated in a confining storage ring. E821 reported the following average value[22] in 2006:

where the first errors are statistical and the second systematic.

The prediction for the value of the muon anomalous magnetic moment includes three parts:

- aμSM = aμQED + aμEW + aμhad.

The difference between the g-factors of the muon and the electron is due to their difference in mass. Because of the muon's larger mass, contributions to the theoretical calculation of its anomalous magnetic dipole moment from Standard Model weak interactions and from contributions involving hadrons are important at the current level of precision, whereas these effects are not important for the electron. The muon's anomalous magnetic dipole moment is also sensitive to contributions from new physics beyond the Standard Model, such as supersymmetry. For this reason, the muon's anomalous magnetic moment is normally used as a probe for new physics beyond the Standard Model rather than as a test of QED.[23] Muon g−2, a new experiment at Fermilab using the E821 magnet will improve the precision of this measurement.[24]

In 2020 an international team of 170 physicists calculated the most accurate prediction for the theoretical value of the muon's anomalous magnetic moment.[25][26]

Muon radiography and tomography

Since muons are much more deeply penetrating than X-rays or gamma rays, muon imaging can be used with much thicker material or, with cosmic ray sources, larger objects. One example is commercial muon tomography used to image entire cargo containers to detect shielded nuclear material, as well as explosives or other contraband.[27]

The technique of muon transmission radiography based on cosmic ray sources was first used in the 1950s to measure the depth of the overburden of a tunnel in Australia[28] and in the 1960s to search for possible hidden chambers in the Pyramid of Chephren in Giza.[29] In 2017, the discovery of a large void (with a length of 30 metres minimum) by observation of cosmic-ray muons was reported.[30]

In 2003, the scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory developed a new imaging technique: muon scattering tomography. With muon scattering tomography, both incoming and outgoing trajectories for each particle are reconstructed, such as with sealed aluminum drift tubes.[31] Since the development of this technique, several companies have started to use it.

In August 2014, Decision Sciences International Corporation announced it had been awarded a contract by Toshiba for use of its muon tracking detectors in reclaiming the Fukushima nuclear complex.[32] The Fukushima Daiichi Tracker (FDT) was proposed to make a few months of muon measurements to show the distribution of the reactor cores.

In December 2014, Tepco reported that they would be using two different muon imaging techniques at Fukushima, "Muon scanning method" on Unit 1 (the most badly damaged, where the fuel may have left the reactor vessel) and "Muon scattering method" on Unit 2.[33]

The International Research Institute for Nuclear Decommissioning IRID in Japan and the High Energy Accelerator Research Organization KEK call the method they developed for Unit 1 the muon permeation method; 1,200 optical fibers for wavelength conversion light up when muons come into contact with them.[34] After a month of data collection, it is hoped to reveal the location and amount of fuel debris still inside the reactor. The measurements began in February 2015.[35]

See also

- Muonic atoms

- Muon spin spectroscopy

- Muon-catalyzed fusion

- Muon tomography

- Comet (experiment), searching for the elusive coherent neutrino-less conversion of a muon to an electron in J-PARC

- Mu2e, an experiment to detect neutrinoless conversion of muons to electrons

- List of particles

References

- "Fundamental Physical Constants from NIST". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. US National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Beringer, J.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2012). "Leptons (e, mu, tau, ... neutrinos ...)" (PDF). PDGLive Particle Summary. Particle Data Group. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Patrignani, C.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2016). "Review of Particle Physics" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 40 (10): 100001. Bibcode:2016ChPhC..40j0001P. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/40/10/100001. hdl:1983/989104d6-b9b4-412b-bed9-75d962c2e000.

- Street, J.; Stevenson, E. (1937). "New evidence for the existence of a particle of mass intermediate between the proton and electron". Physical Review. 52 (9): 1003. Bibcode:1937PhRv...52.1003S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.52.1003. S2CID 1378839.

- Yukawa, Hideki (1935). "On the interaction of elementary particles" (PDF). Proceedings of the Physico-Mathematical Society of Japan. 17 (48): 139–148.

- Bartusiak, Marcia (27 September 1987). "Who ordered the muon?". Science & Technology. The New York Times. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Demtröder, Wolfgang (2006). Experimentalphysik. 1 (4 ed.). Springer. p. 101. ISBN 978-3-540-26034-9.

- Wolverton, Mark (September 2007). "Muons for peace: New way to spot hidden nukes gets ready to debut". Scientific American. 297 (3): 26–28. Bibcode:2007SciAm.297c..26W. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0907-26. PMID 17784615.

- "Physicists announce latest muon g-2 measurement" (Press release). Brookhaven National Laboratory. 30 July 2002. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Baldini, A.M.; et al. (MEG collaboration) (May 2016). "Search for the lepton flavour violating decay μμ+ → e+γ with the full dataset of the MEG experiment". arXiv:1605.05081 [hep-ex].

- Fleming, D. G.; Arseneau, D. J.; Sukhorukov, O.; Brewer, J. H.; Mielke, S. L.; Schatz, G. C.; Garrett, B. C.; Peterson, K. A.; Truhlar, D. G. (28 January 2011). "Kinetic Isotope Effects for the Reactions of Muonic Helium and Muonium with H2". Science. 331 (6016): 448–450. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..448F. doi:10.1126/science.1199421. PMID 21273484. S2CID 206530683.

- Moncada, F.; Cruz, D.; Reyes, A (2012). "Muonic alchemy: Transmuting elements with the inclusion of negative muons". Chemical Physics Letters. 539: 209–221. Bibcode:2012CPL...539..209M. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2012.04.062.

- Moncada, F.; Cruz, D.; Reyes, A. (10 May 2013). "Electronic properties of atoms and molecules containing one and two negative muons". Chemical Physics Letters. 570: 16–21. Bibcode:2013CPL...570...16M. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2013.03.004.

- Coombes, R.; Flexer, R.; Hall, A.; Kennelly, R.; Kirkby, J.; Piccioni, R.; et al. (2 August 1976). "Detection of π−μ coulomb bound states". Physical Review Letters. American Physical Society (APS). 37 (5): 249–252. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.37.249. ISSN 0031-9007.

- Aronson, S.H.; Bernstein, R.H.; Bock, G.J.; Cousins, R. D.; Greenhalgh, J.F.; Hedin, D.; et al. (19 April 1982). "Measurement of the rate of formation of pi-mu atoms in decay". Physical Review Letters. American Physical Society (APS). 48 (16): 1078–1081. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.48.1078. ISSN 0031-9007.

- TRIUMF Muonic Hydrogen collaboration. "A brief description of Muonic Hydrogen research". Retrieved 2010-11-07

- Antognini, A.; Nez, F.; Schuhmann, K.; Amaro, F. D.; Biraben, F.; Cardoso, J. M. R.; et al. (2013). "Proton Structure from the Measurement of 2S-2P Transition Frequencies of Muonic Hydrogen" (PDF). Science. 339 (6118): 417–420. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..417A. doi:10.1126/science.1230016. hdl:10316/79993. PMID 23349284. S2CID 346658.

- Mohr, Peter J.; Newell, David B.; Taylor, Barry N. (2015). "CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2014". Zenodo. arXiv:1507.07956. doi:10.5281/zenodo.22827.

- Wood, B. (3–4 November 2014). "Report on the Meeting of the CODATA Task Group on Fundamental Constants" (PDF). BIPM. p. 7.

- Carlson, Carl E. (May 2015). "The Proton Radius Puzzle". Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics. 82: 59–77. arXiv:1502.05314. Bibcode:2015PrPNP..82...59C. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2015.01.002. S2CID 54915587.

- "The Muon g-2 Experiment Home Page". G-2.bnl.gov. 8 January 2004. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- "(from the July 2007 review by Particle Data Group)" (PDF). Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- Hagiwara, K; Martin, A; Nomura, D; Teubner, T (2007). "Improved predictions for g−2 of the muon and αQED(MZ2)". Physics Letters B. 649 (2–3): 173–179. arXiv:hep-ph/0611102. Bibcode:2007PhLB..649..173H. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2007.04.012. S2CID 118565052.

- "Revolutionary muon experiment to begin with 3,200 mile move of 50 foot-wide particle storage ring" (Press release). 8 May 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Jerald Pinson (11 June, 2020). "Physicists publish worldwide consensus of muon magnetic moment"; Fermilab News; Femilab Research Alliance LLC; US Dept. of Energy:Office of Science, Batavia , Illinois

- T. Aoyama, N. Asmussen, M. Benayoun, J. Bijnens, T. Blum, M. Bruno, I. Caprini, C. M. Carloni Calame, M. Cè, G. Colangelo, F. Curciarello, H. Czyż, I. Danilkin, M. Davier, C. T. H. Davies, M. Della Morte, S. I. Eidelman, A. X. El-Khadra, A. Gérardin, D. Giusti, M. Golterman, Steven Gottlieb, V. Gülpers, F. Hagelstein, M. Hayakawa, G. Herdoíza, D. W. Hertzog, A. Hoecker, M. Hoferichter, B.-L. Hoid, R. J. Hudspith, F. Ignatov, T. Izubuchi, F. Jegerlehner, L. Jin, A. Keshavarzi, T. Kinoshita, B. Kubis, A. Kupich, A. Kupść, L. Laub, C. Lehner, L. Lellouch, I. Logashenko, B. Malaescu, K. Maltman, M. K. Marinković, P. Masjuan, A. S. Meyer, H. B. Meyer, T. Mibe, K. Miura, S. E. Müller, M. Nio, D. Nomura, A. Nyffeler, V. Pascalutsa, M. Passera, E. Perez del Rio, S. Peris, A. Portelli, M. Procura, C. F. Redmer, B. L. Roberts, P. Sánchez-Puertas, S. Serednyakov, B. Shwartz, S. Simula, D. Stöckinger, H. Stöckinger-Kim, P. Stoffer, T. Teubner, R. Van de Water, M. Vanderhaeghen, G. Venanzoni, G. von Hippel, H. Wittig, Z. Zhang, M. N. Achasov, A. Bashir, N. Cardoso, B. Chakraborty, E.-H. Chao, J. Charles, A. Crivellin, O. Deineka, A. Denig, C. DeTar, C. A. Dominguez, A. E. Dorokhov, V. P. Druzhinin, G. Eichmann, M. Fael, C. S. Fischer, E. Gámiz, Z. Gelzer, J. R. Green, S. Guellati-Khelifa, D. Hatton, N. Hermansson-Truedsson, A.S. Zhevlakov; (3 December, 2020). " The anomalous magnetic moment of the muon in the Standard Model "; Physical Reports, pp. 1-166, Vol. 887; Elsevier B.V.; Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- "Decision Sciences Corp".

- George, E.P. (1 July 1955). "Cosmic rays measure overburden of tunnel". Commonwealth Engineer: 455.

- Alvarez, L.W. (1970). "Search for hidden chambers in the pyramids using cosmic rays". Science. 167 (3919): 832–839. Bibcode:1970Sci...167..832A. doi:10.1126/science.167.3919.832. PMID 17742609.

- Morishima, Kunihiro; Kuno, Mitsuaki; Nishio, Akira; Kitagawa, Nobuko; Manabe, Yuta (2017). "Discovery of a big void in Khufu's Pyramid by observation of cosmic-ray muons". Nature. 552 (7685): 386–390. arXiv:1711.01576. Bibcode:2017Natur.552..386M. doi:10.1038/nature24647. PMID 29160306. S2CID 4459597.

- Borozdin, Konstantin N.; Hogan, Gary E.; Morris, Christopher; Priedhorsky, William C.; Saunders, Alexander; Schultz, Larry J.; Teasdale, Margaret E. (2003). "Radiographic imaging with cosmic-ray muons". Nature. 422 (6929): 277. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..277B. doi:10.1038/422277a. PMID 12646911. S2CID 47248176.

- "Decision Sciences awarded Toshiba contract for Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Complex project" (Press release). Decision Sciences. 8 August 2014.

- "Tepco to start "scanning" inside of Reactor 1 in early February by using muons". Fukushima Diary. January 2015.

- "Muon measuring instrument production for "muon permeation method" and its review by international experts". IRID.or.jp.

- "Muon scans begin at Fukushima Daiichi". SimplyInfo. 3 February 2015.

Further reading

- Neddermeyer, S.H.; Anderson, C.D. (1937). "Note on the Nature of Cosmic-Ray Particles" (PDF). Physical Review. 51 (10): 884–886. Bibcode:1937PhRv...51..884N. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.51.884.

- Street, J.C.; Stevenson, E.C. (1937). "New evidence for the existence of a particle of mass intermediate between the Proton and electron". Physical Review. 52 (9): 1003–1004. Bibcode:1937PhRv...52.1003S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.52.1003. S2CID 1378839.

- Feinberg, G.; Weinberg, S. (1961). "Law of Conservation of Muons". Physical Review Letters. 6 (7): 381–383. Bibcode:1961PhRvL...6..381F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.6.381.

- Serway; Faughn (1995). College Physics (4th ed.). Saunders. p. 841.

- Knecht, M. (2003). "The Anomalous Magnetic Moments of the Electron and the Muon". In Duplantier, B.; Rivasseau, V. (eds.). Poincaré Seminar 2002: Vacuum Energy – Renormalization. Progress in Mathematical Physics. 30. Birkhäuser Verlag. p. 265. ISBN 978-3-7643-0579-6.

- Derman, E. (2004). My Life as a Quant. Wiley. pp. 58–62.

External links

Media related to Muons at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Muons at Wikimedia Commons- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Muon anomalous magnetic moment and supersymmetry (28 August 2005)

- "g-2 experiment".

muon anomalous magnetic moment

- "muLan experiment". Archived from the original on 2 September 2006.

Measurement of the Positive Muon Lifetime

- "The Review of Particle Physics".

- "The TRIUMF Weak Interaction Symmetry Test".

- "The MEG Experiment". Archived from the original on 25 March 2002.

Search for the decay Muon → Positron + Gamma

- King, Philip. "Making Muons". Backstage Science. Brady Haran.