Blaxploitation

Blaxploitation or blacksploitation is an ethnic subgenre of the exploitation film that emerged in the United States during the early 1970s. The films, while popular, suffered backlash for disproportionate numbers of stereotypical film characters showing bad or questionable motives, including most roles as criminals resisting arrest. However, the genre does rank among the first in which black characters and communities are the heroes and subjects of film and television, rather than sidekicks, villains, or victims of brutality.[1] The genre's inception coincides with the rethinking of race relations in the 1970s.

Blaxploitation films were originally aimed at an urban African-American audience,[2] but the genre's audience appeal soon broadened across racial and ethnic lines. Hollywood realized the potential profit of expanding the audiences of blaxploitation films across those racial lines.

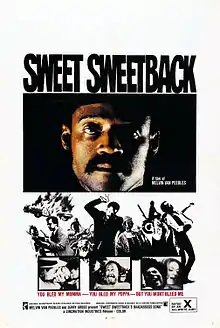

Variety credited Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song and the less radical, Hollywood-financed film Shaft (both released in 1971) with the invention of the blaxploitation genre.[3] Blaxploitation films were also the first to feature soundtracks of funk and soul music.[4]

Description

General themes

[S]upercharged, bad-talking, highly romanticized melodramas about Harlem superstuds, the pimps, the private eyes and the pushers who more or less singlehandedly make whitey's corrupt world safe for black pimping, black private-eyeing and black pushing.

Blaxploitation films set in the Northeast or West Coast mainly take place in poor urban neighborhoods. Pejorative terms for white characters, such as "cracker" and "honky," are commonly used. Blaxploitation films set in the South often deal with slavery and miscegenation.[6][7] The genre's films are often bold in their statements and utilize violence, sex, drug trade, and other shocking qualities to provoke the audience.[1] The films usually portray black protagonists overcoming "The Man" or emblems of the white majority that oppresses the Black community.

Blaxploitation includes several subtypes, including crime (Foxy Brown), action/martial arts (Three the Hard Way), westerns (Boss Nigger), horror (Abby, Blacula), prison (Penitentiary), comedy (Uptown Saturday Night), nostalgia (Five on the Black Hand Side), coming-of-age/courtroom drama (Cooley High/Cornbread, Earl and Me), and musical (Sparkle).

Following the example set by Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, many blaxploitation films feature funk and soul jazz soundtracks with heavy bass, funky beats, and wah-wah guitars. These soundtracks are notable for complexity that was not common to the radio-friendly funk tracks of the 1970s. They also often feature a rich orchestration which included flutes and violins.[8]

Following the popularity of these films in the 1970s, movies within other genres began to feature black characters with stereotypical blaxploitation characteristics, such as the Harlem underworld characters in the James Bond film Live and Let Die (1973), Jim Kelly's character in Enter the Dragon (1973), and Fred Williamson's character in The Inglorious Bastards (1978).

Black Power

Afeni Shakur claimed that every aspect of culture (including cinema) in the 1960s and 1970s was influenced by the Black Power movement. Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song was one of the first films to incorporate black power ideology and permit black actors to be the stars of their own narratives, rather than being relegated to the typical roles available to them (such as the "mammy" figure and other low-status characters).[9][10] Films such as Shaft brought the black experience to film in a new way, allowing black political and social issues that had previously been ignored in cinema to be explored. Shaft and its protagonist, John Shaft, brought African American culture to the mainstream world.[10] Sweetback and Shaft were both influenced by the black power movement, containing Marxist themes, solidarity, and social consciousness alongside the genre-typical images of sex and violence.

Knowing that film could bring about social and cultural change, the Black Power movement seized the genre to highlight black socioeconomic struggles in the 1970s; many such films contained black heroes who were able to overcome the institutional oppression of African American culture and history.[1] Later films such as Superfly softened the rhetoric of black power, encouraging resistance within the capitalist system rather than a radical transformation of society. Superfly did, however, still embrace the black nationalist movement in its argument that black and white authority cannot coexist easily.

Stereotypes

The genre's role in exploring and shaping race relations in the United States has been controversial. Some held that the blaxploitation trend was a token of black empowerment,[11] but others accused the movies of perpetuating common white stereotypes about black people. As a result, many called for the end of the genre. The NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and National Urban League joined to form the Coalition Against Blaxploitation. Their influence in the late 1970s contributed to the genre's demise. Literary critic Addison Gayle wrote in 1974, "The best example of this kind of nihilism / irresponsibility are the Black films; here is freedom pushed to its most ridiculous limits; here are writers and actors who claim that freedom for the artist entails exploitation of the very people to whom they owe their artistic existence."[12]

Films such as Superfly and The Mack received intense criticism not only for the stereotype of the protagonist (generalizing pimps as representative of all African-American men, in this case), but also for portraying all black communities as hotbeds for drug trade and crime.

Blaxploitation films such as Mandingo (1975) provided mainstream Hollywood producers, in this case Dino De Laurentiis, a cinematic way to depict plantation slavery with all of its brutal, historical and ongoing racial contradictions and controversies, including sex, miscegenation, rebellion and so on. The story world also depicts the plantation as one of the main origins of boxing as a sport in the U.S.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a new wave of acclaimed black filmmakers, particularly Spike Lee (Do the Right Thing), John Singleton (Boyz n the Hood), and Allen and Albert Hughes (Menace II Society) focused on black urban life in their movies. These directors made use of blaxploitation elements while incorporating implicit criticism of the genre's glorification of stereotypical "criminal" behavior.

Alongside accusations of exploiting stereotypes, the NAACP also criticized the blaxploitation genre of exploiting the entire black community and culture of America, by creating films for a profit that those communities would never see, despite being the vastly misrepresented main focus of many blaxploitation film plots. Many film professionals today still believe that there is no truly equal "Black Hollywood," as evidenced by the "Oscars So White" scandal in 2015 that caused uproar when no black actors were nominated for "Best Actor" Oscar Awards.[10]

Slavesploitation

Slavesploitation, a subgenre of blaxploitation in literature and film, flourished briefly in the late 1960s and 1970s.[13][14] As its name suggests, the genre is characterized by sensationalistic depictions of slavery.

Abrams, arguing that Quentin Tarantino's Django Unchained (2012) finds its historical roots in the slavesploitation genre, observes that slavesploitation films are characterized by "crassly exploitative representations of oppressed slave protagonists".[15]

One early antecedent of the genre is Slaves (1969), which Gaines notes was "not 'slavesploitation' in the vein of later films", but which nonetheless featured graphic depictions of beatings and sexual violence against slaves.[16] Novotny argues that Blacula (1972), although it does not depict slavery directly, is historically linked to the slavesploitation subgenre.[17]

By far the best-known and best-studied exemplar of slavesploitation is Mandingo, a 1957 novel which was adapted into a 1961 play and a 1975 film. Indeed, Mandingo was so well known that a contemporary reviewer of Die the Long Day, a 1972 novel by Orlando Patterson, called it an example of the "Mandingo genre".[18] The film, panned on its release, has been subject to widely divergent critical assessments.[19] Robin Wood, for instance, argued in 1998 that it is "greatest film about race ever made in Hollywood, certainly prior to Spike Lee and in some respects still".[20]

Legacy

Influence

Blaxploitation films have had an enormous and complicated influence on American cinema. Filmmaker and exploitation film fan Quentin Tarantino, for example, has made numerous references to the blaxploitation genre in his films. An early blaxploitation tribute can be seen in the character of "Lite," played by Sy Richardson, in Repo Man (1984). Richardson later wrote Posse (1993), which is a kind of blaxploitation Western.

Some of the later, blaxploitation-influenced movies such as Jackie Brown (1997), Undercover Brother (2002), Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002), Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003), and Django Unchained (2012) feature pop culture nods to the genre. The parody Undercover Brother, for example, stars Eddie Griffin as an afro-topped agent for a clandestine organization satirically known as the "B.R.O.T.H.E.R.H.O.O.D.". Likewise, Austin Powers in Goldmember co-stars Beyoncé Knowles as the Tamara Dobson/Pam Grier-inspired heroine, Foxxy Cleopatra. In the 1977 parody film The Kentucky Fried Movie, a mock trailer for Cleopatra Schwartz depicts another Grier-like action star married to a rabbi. In a famous scene in Reservoir Dogs, the protagonists discuss Get Christie Love!, a mid-1970s blaxploitation television series. In the catalytic scene of True Romance, the characters watch the movie The Mack.

John Singleton's Shaft (2000), starring Samuel L. Jackson, is a modern-day interpretation of a classic blaxploitation film. The 1997 film Hoodlum starring Laurence Fishburne portrays a fictional account of black mobster Ellsworth "Bumpy" Johnson and recasts gangster blaxploitation with a 1930s twist. In 2004, Mario Van Peebles released Baadasssss!, about the making of his father's movie (Mario plays his father). 2007's American Gangster, based on the true story of heroin dealer Frank Lucas, takes place in the early 1970s in Harlem and has many elements similar in style to blaxploitation films, specifically its prominent featuring of the song "Across 110th Street".

Blaxploitation films have profoundly impacted contemporary hip-hop culture. Several prominent hip hop artists, including Snoop Dogg, Big Daddy Kane, Ice-T, Slick Rick, and Too Short, have adopted the no-nonsense pimp persona popularized first by ex-pimp Iceberg Slim's 1967 book Pimp and subsequently by films such as Super Fly, The Mack, and Willie Dynamite. In fact, many hip-hop artists have paid tribute to pimping within their lyrics (most notably 50 Cent's hit single "P.I.M.P.") and have openly embraced the pimp image in their music videos, which include entourages of scantily-clad women, flashy jewelry (known as "bling"), and luxury Cadillacs (referred to as "pimpmobiles"). The most famous scene of The Mack, featuring the "Annual Players Ball", has become an often-referenced pop culture icon—most recently by Chappelle's Show, where it was parodied as the "Playa Hater's Ball". The genre's overseas influence extends to artists such as Norway's hip-hop duo Madcon.[21]

In Michael Chabon's novel Telegraph Avenue, set in 2004, two characters are former blaxploitation stars.[22]

In 1980, opera director Peter Sellars (not to be confused with actor Peter Sellers) produced and directed a staging of Mozart's opera Don Giovanni in the manner of a blaxploitation film, set in contemporary Spanish Harlem, with African-American singers portraying the anti-heroes as street-thugs, killing by gunshot rather than with a sword, using recreational drugs, and partying almost naked.[23] It was later released on commercial video and can be seen on YouTube.[24]

A 2016 video game, Mafia III, is set in the year 1968 and revolves around Lincoln Clay, a mixed-race African American orphan raised by "black mob".[25] After the murder of his surrogate family at the hands of the Italian mafia, Lincoln Clay seeks vengeance on those who took away the only thing that mattered to him.

Cultural references

The notoriety of the blaxploitation genre has led to many parodies.[26] The earliest attempts to mock the genre, Ralph Bakshi's Coonskin and Rudy Ray Moore's Dolemite, date back to the genre's heyday in 1975.

Coonskin was intended to deconstruct racial stereotypes, from early minstrel show stereotypes to more recent stereotypes found in blaxploitation film itself. The work stimulated great controversy even before its release when the Congress of Racial Equality challenged it. Even though distribution was handed to a smaller distributor who advertised it as an exploitation film, it soon developed a cult following with black viewers.[3]

Dolemite, less serious in tone and produced as a spoof, centers around a sexually active black pimp played by Rudy Ray Moore, who based the film on his stand-up comedy act. A sequel, The Human Tornado, followed.

Later spoofs parodying the blaxploitation genre include I'm Gonna Git You Sucka, Pootie Tang, Undercover Brother, Black Dynamite, and The Hebrew Hammer, which featured a Jewish protagonist and was jokingly referred to by its director as a "Jewsploitation" film.

Robert Townsend's comedy Hollywood Shuffle features a young black actor who is tempted to take part in a white-produced blaxploitation film.

The satirical book Our Dumb Century features an article from the 1970s entitled "Congress Passes Anti-Blaxploitation Act: Pimps, Players Subject to Heavy Fines".

FOX's network television comedy, "MADtv", has frequently spoofed the Rudy Ray Moore-created franchise Dolemite, with a series of sketches performed by comic actor Aries Spears, in the role of "The Son of Dolemite". Other sketches include the characters "Funkenstein", "Dr. Funkenstein" and more recently Condoleezza Rice as a blaxploitation superhero. A recurring theme in these sketches is the inexperience of the cast and crew in the blaxploitation era, with emphasis on ridiculous scripting and shoddy acting, sets, costumes, and editing. The sketches are testaments to the poor production quality of the films, with obvious boom mike appearances and intentionally poor cuts and continuity.

Another of FOX's network television comedies, "Martin" starring Martin Lawrence, frequently references the blaxploitation genre. In the Season Three episode "All The Players Came", when Martin organizes a "Player's Ball" charity event to save a local theater, several stars of the blaxploitation era, such as Rudy Ray Moore, Antonio Fargas, Dick Anthony Williams and Pam Grier all make cameo appearances. In one scene, Martin, in character as aging pimp "Jerome", refers to Pam Grier as "Sheba, Baby" in reference to her 1975 blaxploitation feature film of the same name.

In the movie Leprechaun in the Hood, a character played by Ice-T pulls a baseball bat from his Afro. This scene alludes to a similar scene in Foxy Brown, in which Pam Grier hides a small semi-automatic pistol in her Afro.

Adult Swim's Aqua Teen Hunger Force series has a recurring character called "Boxy Brown" - a play on Foxy Brown. An imaginary friend of Meatwad, Boxy Brown is a cardboard box with a crudely drawn face with a French cut that dons an afro. Whenever Boxy speaks, '70s funk music, typical of blaxploitation films, plays in the background. The cardboard box also has a confrontational attitude and dialect similar to many heroes of this film genre.

Some of the TVs found in the action video game Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne feature a Blaxploitation-themed parody of the original Max Payne game called Dick Justice, after its main character. Dick behaves much like the original Max Payne (down to the "constipated" grimace and metaphorical speech) but wears an afro and mustache and speaks in Ebonics.

Duck King, a fictional character created for the video game series Fatal Fury, is a prime example of foreign black stereotypes.

The sub-cult movie short Gayniggers from Outer Space is a blaxploitation-like science fiction oddity directed by Danish filmmaker, DJ, and singer Morten Lindberg.

Jefferson Twilight, a character in The Venture Bros., is a parody of the comic-book character Blade (a black, half human, half-vampire vampire hunter), as well as a blaxploitation reference. He has an afro, sideburns, and a mustache. He carries swords, dresses in stylish 1970s clothing, and says that he hunts "Blaculas". He looks and sounds like Samuel L. Jackson.

The intro credits of Beavis and Butt-Head Do America feature a blaxploitation-style theme sung by Isaac Hayes.

A scene from the Season 9 episode of The Simpsons, Simpson Tide", shows Homer Simpson watching "Exploitation Theatre." A voice-over announces the fake movie titles, "Blackula," "Blackenstein," and "The Blunch Black of Blotre Blame."

Family Guy has parodied blaxploitation numerous times using fake movie titles such as "Black to the Future" (Back to the Future) and "Love Blactually" (Love Actually). These parodies occasionally feature a stereotyped black version of Peter Griffin.

Martha Southgate's 2005 novel Third Girl from the Left is set in Hollywood during the era of blaxploitation films and references many blaxploitation films and stars such as Pam Grier and Coffy.

Notable blaxploitation films

1970

- The Black Angels is about a black motorcycle gang and is part of the outlaw biker film genre.

- They Call Me MISTER Tibbs! This sequel to In the Heat of the Night is a pre-Shaft blaxploitation film. It is stylistically different from the original film.

- Cotton Comes to Harlem is based on a novel written by Chester Himes and directed by Ossie Davis. Features two black NYPD detectives, Coffin Ed Johnson (played by Raymond St. Jacques) and Gravedigger Jones (played by Godfrey Cambridge), on the hunt for a money-filled cotton bale stolen by a corrupt reverend named Deke O'Malley. Blazing Saddles star Cleavon Little appears, as does comedian Redd Foxx in a role which led to his TV series Sanford & Son.

1971

- Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song is written, produced, scored, directed by, and stars Melvin Van Peebles. The hero, named Sweetback because of his sexual powers, is an apolitical sex worker. His pimp, Beadle, makes a deal with a couple of police officers to let them take Sweetback into the station so it looks like the cops are picking up suspects. While Sweetback is in custody, the police arrest a young black militant and take him to a rural area to torture him. Sweetback steps in and beats the police unconscious. With the police chasing him, Sweetback comes to understand the power of the black community sticking together. He uses his ingenuity and survival skills to outwit the police and escape to Mexico.[27]

- Shaft is directed by Gordon Parks and features Richard Roundtree as detective John Shaft. The soundtrack features contributions from Isaac Hayes, whose recording of the titular song won several awards, including an Academy Award. Shaft was deemed culturally relevant by the Library of Congress, and it spawned two sequels, Shaft's Big Score (1972) and Shaft in Africa (1973), as well as a short-lived TV series starring Roundtree.[28] The concept was revived in 2000 with an all-new sequel starring Samuel L. Jackson as the nephew of the original John Shaft, with Richard Roundtree reprising his role as the original Shaft.

1972

- Hit Man is the story of an Oakland hit man, played by former NFL player Bernie Casey, who comes to Los Angeles after his brother is murdered. He learns that his niece has been forced into pornography. She is eventually murdered. He sets out to murder everyone directly involved, from a porn star (Pam Grier), to a theater owner (Ed Cambridge), to a man he looked up to as a child (Rudy Challenger), and a mobster (Don Diamond).

- Super Fly is directed by Gordon Parks Jr. and features a soundtrack by Curtis Mayfield. Super Fly is one of the most controversial, profitable, and popular classics of the genre.[29]

- The Legend of Nigger Charley is written by, co-produced by, and stars Fred Williamson. It was followed by the 1973 sequel, The Soul of Nigger Charley.

- Hammer stars Fred Williamson as B.J. Hammer, a boxer who gets mixed up with a crooked manager who wants him to throw a fight for the Mafia.

- Across 110th Street is a crime thriller about two detectives (played by Anthony Quinn and Yaphet Kotto) who try to catch a group of robbers who stole $300,000 from the Mob before the Mob catches up with them. The title track by Bobby Womack reached #19 on the Billboard Black Singles Chart.

- Black Mama, White Mama is a women in prison film exploitation movie partly inspired by The Defiant Ones (1958) starring Pam Grier and Margaret Markov in the roles originally played by Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis.

- Blacula is a take on Dracula which features an African prince (played by William H. Marshall) who is bitten and imprisoned by Count Dracula. Once freed from his coffin, he spreads terror in modern-day Los Angeles.

- Slaughter stars Jim Brown as an ex-Green Beret who seeks revenge against a crime syndicate for the murder of his parents. It spawned the sequel, Slaughter's Big Rip-Off (1973).

- Trouble Man stars Robert Hooks as "Mr. T.", a hard-edged private detective who tends to take justice into his own hands. Although the film itself was unsuccessful, it did enjoy a successful soundtrack written, produced, and performed by Motown artist Marvin Gaye.

1973

- In Black Caesar, Tommy Gibbs (Fred Williamson) is a street-smart hoodlum who has worked his way up to being the crime boss of Harlem.

- Blackenstein is a parody of Frankenstein and features a black Frankenstein's monster.

- Cleopatra Jones and its sequel, Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold (1975) star Tamara Dobson as a karate-chopping government agent. The first film marks the beginning of a subgenre of blaxploitation films focusing on strong female leads taking an active role in shootouts and fights. Some of these films include Coffy, Black Belt Jones, Foxy Brown, and T.N.T. Jackson.

- In Coffy, Pam Grier stars as Coffy, a nurse turned vigilante who takes revenge on all those who hooked her 11-year-old sister on heroin. Coffy marks Pam Grier's biggest hit and was re-worked for Foxy Brown, Friday Foster, and Sheba Baby.

- Detroit 9000 is set in Detroit, MI and features street-smart white detective Danny Bassett (Alex Rocco) who teams with educated black detective Sgt. Jesse Williams (Hari Rhodes) to investigate the theft of $400,000 at a fund-raiser for Representative Aubrey Hale Clayton (Rudy Challenger). Championed by Quentin Tarantino, it was released on video by Miramax in April 1999.

- Gordon's War stars Paul Winfield as a Vietnam vet who recruits ex-Army buddies to fight the Harlem drug dealers and pimps responsible for the heroin-fueled death of his wife.

- Live and Let Die is the eighth film in the James Bond series. James Bond (Roger Moore) battles gangsters led by Caribbean dictator Dr. Kananga (Yaphet Kotto) who doubles as drug lord "Mr. Big", in Harlem, New Orleans, and the Caribbean while investigating the mysterious murders of three MI6 agents.

- The Mack is a film starring Max Julien and Richard Pryor.[30] This movie was produced during the era of such Blaxploitation movies as Dolemite. It is not considered by its makers a true blaxploitation picture. It is more a social commentary according to Mackin' Ain't Easy, a documentary about the making of The Mack, which can be found on the DVD edition of the film. The movie tells the story of the life of John Mickens (a.k.a. Goldie), a former drug dealer recently released from prison who becomes a big-time pimp. Standing in his way is another pimp: Pretty Tony. Two corrupt white cops, a local crime lord, and his own brother (a black nationalist), all try to force him out of the business. The movie is set in Oakland, California and was the biggest grossing blaxploitation film of its time. Its soundtrack was recorded by Motown artist Willie Hutch.

- Scream Blacula Scream is the sequel to Blacula. William H. Marshall reprises his role as Blacula/Mamuwalde.

- Slaughter's Big Rip-Off features Jim Brown continuing his battle against the Mob in this sequel to Slaughter (1972).

- The Spook Who Sat By the Door is adapted from Sam Greenlee's novel and directed by Ivan Dixon with music by Herbie Hancock. A token black CIA employee, who is secretly a black nationalist, leaves his position to train a street gang in CIA tactics to become an army of "freedom fighters". The film was reportedly pulled from distribution because of its politically controversial message and depictions of an American race war. Until its 2004 DVD release, it was hard to find, save for infrequent bootleg VHS copies. In 2012, the film was included in the USA Library of Congress National Film Registry.[31]

- That Man Bolt, starring Fred Williamson, is the first spy film in this genre, combining elements of James Bond with martial arts action in an international setting.

- Trick Baby is based on the book of the same name by ex-pimp Iceberg Slim.

- Hell Up In Harlem is the sequel to Black Caesar and stars Fred Williamson and Gloria Hendry, with a soundtrack by Motown singer Edwin Starr.

1974

- Abby is a version of The Exorcist and stars Carol Speed as a virtuous young woman possessed by a demon. Ms. Speed also sings the title song. William H. Marshall (of Blacula fame) conducts the exorcism of Abby on the floor of a discotheque. A hit in its time, it was later pulled from the theaters after Warner Bros. successfully sued AIP over copyright issues.

- In Black Belt Jones, Jim Kelly, who is better known for his role as "Mister Williams" in the Bruce Lee film Enter the Dragon, is given a leading role. He plays Black Belt Jones, a federal agent/martial arts expert who takes on the mob as he avenges the murder of a karate school owner.

- Black Eye is an action-mystery starring Fred Williamson as a private detective investigating murders connected with a drug ring.

- The Black Godfather stars Rod Perry as a man rising to underworld power based on The Godfather.

- The Black Six is about a black motorcycle gang seeking revenge. It combines blaxploitation and outlaw biker film.

- Foxy Brown is largely a remake of the hit film Coffy. Pam Grier once again plays a nurse on a vendetta against a drug ring.[32] Originally written as a sequel to Coffy, the film's working title was Burn, Coffy, Burn!. The soundtrack was recorded by Willie Hutch.

- Get Christie Love! is a TV movie later released to some theaters. This police drama, starring an attractive young black woman (Teresa Graves) as an undercover cop, was later made into a short-lived TV series.

- Johnny Tough stars Dion Gossett and Renny Roker.

- Space Is the Place is a psychedelically-themed blaxploitation film featuring Sun Ra & His Intergalactic Solar Arkestra.

- Sugar Hill is set in Houston and features a female fashion photographer (played by Marki Bey) who wreaks revenge on the local crime Mafia that murdered her fiancé with the use of voodoo magic.

- Three the Hard Way features three black men (Fred Williamson, Jim Kelly, and Jim Brown) who must stop a white supremacist plot to eliminate all blacks with a serum in the water supply. Directed by Gordon Parks Jr.

- TNT Jackson stars Jean Bell (one of the first black Playboy playmates) and is partly set in Hong Kong. It is notable for blending blaxploitation with the then-popular "chop-socky" martial arts genre.

- Together Brothers is set in Galveston, Texas, where a street gang solves the murder of a Galveston, TX police officer (played by Ed Bernard who has been a mentor to the gang leader). This was the first blaxploitation film to feature a transgender character as the villain. Galveston, TX native Barry White composed the film's score. The soundtrack features music by the Love Unlimited Orchestra.

- Truck Turner stars Isaac Hayes, Yaphet Kotto, and Nichelle Nichols. Jonathan Kaplan directs. Former football player turned bounty hunter is pitted against a powerful prostitution crime syndicate in Los Angeles.

- In Willie Dynamite, Roscoe Orman (Gordon from Sesame Street fame) plays a pimp. As in many blaxploitation films, the lead character drives a customized Cadillac Eldorado Coupe (the same car was used in Magnum Force).

1975

- In Sheba, Baby, a female private eye (Pam Grier) tries to help her father save his loan business from a gang of thugs.

- In The Black Gestapo, Rod Perry plays General Ahmed, who has started an inner-city People's Army to try to relieve the misery of the citizens of Watts, Los Angeles. When the Mafia moves in, they establish a military-style squad.

- Black Shampoo is a take-off of the Warren Beatty hit Shampoo.

- In Boss Nigger, along with his friend Amos (D'Urville Martin), Boss Nigger (Fred Williamson) takes over the vacated position of Sheriff in a small western town in this Western blaxploitation film. Because of its controversial title, it was released in some markets as The Boss, The Black Bounty Killer or The Black Bounty Hunter.

- Coonskin is an animated/live-action, controversial Ralph Bakshi film about Br'er Fox, Br'er Rabbit, and Br'er Bear in a blaxploitation parody of Disney's Song of the South. It features the voice of Barry White as Br'er Bear.

- Darktown Strutters is a farce produced by Roger Corman's brother, Gene, and directed by William Witney. A Colonel Sanders-type figure with a chain of urban fried chicken restaurants is trying to wipe out the black race by making them impotent through his drugged fried chicken.

- Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde is the retelling of the Jekyll and Hyde tale, starring Bernie Casey.

- Dolemite is also the name of its principal character, played by Rudy Ray Moore, who co-wrote the film. Moore had developed the alter-ego as a stand-up comedian and released several comedy albums using this persona. The film was directed by D'Urville Martin, who appears as the villain Willie Green. The film has attained cult status, earning it a following and making it more well-known than many of its counterparts. A sequel, The Human Tornado, was released in 1976.

- Mandingo is based on a series of lurid Civil War novels and focuses on the abuses of slavery and the sexual relations between slaves and slave owners. It features Richard Ward and Ken Norton. It was followed by a sequel, Drum (1976) starring Pam Grier.

- The Candy Tangerine Man opens with pageantry pimp Baron (John Daniels) driving his customized two-tone red and yellow Rolls Royce around downtown L.A at night. His ladies have been coming up short lately and he wants to know why. It turns out that two L.A.P.D. cops - Dempsey and Gordon, who have been after Baron for some time now, have resorted to rousting his girls every chance they get. Indeed, in the next scene they have set Baron up with a cop in drag to entrap him with procurement of prostitutes.

- Lady Cocoa, directed by Matt Cimber and starring Lola Falana.

- Welcome Home Brother Charles After being released prison, a wrongfully imprisoned black man takes vengeance on those who previously crossed him by strangling them with his penis.

1976

- Ebony, Ivory & Jade from director Cirio Santiago (also known as She Devils in Chains, American Beauty Hostages, Foxfire, Foxforce), features three female athletes who are kidnapped during an international track meet in Hong Kong and fight their way to freedom. This is another cross-genre blend of blaxploitation and martial arts action films.

- The Muthers is another Cirio Santiago combination of Filipino martial arts action and women-in-prison elements. Jeanne Bell and Jayne Kennedy rescue prisoners held at an evil coffee plantation.

- Passion Plantation (a.k.a. Black Emmanuel, White Emmanuel) is a blend of the Mandingo and Emmanuelle, erotic films with interracial sex and savagery.

- In Velvet Smooth, Johnnie Hill is a female private detective hired to infiltrate the criminal underworld.

- In The Human Tornado a.k.a. Dolemite II, Rudy Ray Moore reprises his role as Dolemite in the sequel to the 1975 film Dolemite.

- In J. D.'s Revenge, a club driver is possessed by a dead gangster who seeks revenge for his murder over 30 years ago.

1977

- Black Fist features a street fighter who goes to work for a white gangster and a corrupt cop. The film is in the public domain. Cast members include Richard Lawson and Dabney Coleman

- Black Samurai is based on a novel of the same name by Marc Olden, is directed by Al Adamson, and stars Jim Kelly. The script is credited to B. Readick, with additional story ideas from Marco Joachim.

- Bare Knuckles stars Robert Viharo, Sherry Jackson, and Gloria Hendry. The film is written and directed by Don Edmonds and follows L.A. bounty hunter Zachary Kane (Viharo) on the hunt for a masked serial killer.

- Petey Wheatstraw (a.k.a. Petey Wheatstraw, the Devil's Son-In-Law) is written by Cliff Roquemore and stars popular blaxploitation genre comedian Rudy Ray Moore along with Jimmy Lynch, Leroy Daniels, Ernest Mayhand, and Ebony Wright. It is typical of Moore's other films of the era, Dolemite and The Human Tornado, in that it features Rudy Ray Moore's rhyming dialogue.

1978

- Death Dimension is a martial arts film directed by Al Adamson and starring Jim Kelly, Harold Sakata, George Lazenby, Terry Moore, and Aldo Ray. The movie also goes by the names Death Dimensions, Freeze Bomb, Icy Death, The Kill Factor, and Black Eliminator. A scientist, Professor Mason, invents a powerful freezing bomb for a gangster leader nicknamed "The Pig" (Sakata).

1979

- Disco Godfather, also known as The Avenging Disco Godfather, is an action film starring Rudy Ray Moore and Carol Speed. Moore's character, a retired cop, owns and operates a disco and tries to shut down the local angel dust dealer after his nephew becomes hooked on the drug.

- Penitentiary, directed by Jamaa Franklin, follows the travails of Martel "Too Sweet" Gordone (played by Leon Isaac Kennedy) after his wrongful imprisonment. Set in a prison, the film exploits all of the tropes of the genre, including violence, sexuality and the eventual triumph of the lead character.

Post-1970s Blaxploitation films

- The Last Dragon (1985) is a martial arts action film with blaxploitation elements.

- I'm Gonna Git You Sucka (1988) is a comedic spoof of classic 1970s blaxploitation and features many of its stars: Jim Brown, Bernie Casey, Antonio Fargas, and Isaac Hayes.

- Action Jackson (1988) is a film where the protagonist Jericho Jackson (Carl Weathers), uses catchphrases to taunt his opponents. Craig T. Nelson, Sharon Stone, and Vanity also star.

- Original Gangstas (1996) brings together 1970s blaxploitation stars Pam Grier, Richard Roundtree, Fred Williamson, and Jim Brown.

- Jackie Brown (1997) stars Pam Grier and Samuel L. Jackson. Director Quentin Tarantino pays homage to the blaxploitation genre. The movie is based on the Elmore Leonard novel Rum Punch. Tarantino's title change, casting of Grier, and 1970s-style poster art, are all references to Grier's 1974 film Foxy Brown.

- Pootie Tang (2001) incorporates many blaxploitation elements comedically.

- Undercover Brother (2002) centers around a blaxploitation-style secret agent.

- Full Clip (2004) is made in the graphic novel style.

- Hookers In Revolt (2008) stars and is directed by Sean Weathers. With its prevalence of pimps and prostitutes, it is an inventive throwback to early 1970s blaxploitation.[33]

- Black Dynamite (2009) stars Michael Jai White and spoofs blaxploitation films.

- Proud Mary (2018) is an action thriller starring Taraji P. Henson & Danny Glover.[34]

- Superfly (2018) is an action crime film and a remake of the 1972 film, starring Trevor Jackson & Jason Mitchell.

- Undercover Brother 2 (2019), a sequel to the 2002 film, replacing Eddie Griffin with Michael Jai White.

Other

- Baadasssss! (2003), a biopic about the making of Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, starring Mario Van Peebles.

- Dolemite Is My Name (2019), a biopic about the making of Dolemite, starring Eddie Murphy.

See also

Further reading

- Blaxploitation Films by Mikel J. Koven, 2010, Kamera Books, ISBN 978-1-903047-58-3

- "The Rise and Fall of Blaxploitation" by Ed Guerrero, in The Wiley-Blackwell History of American Film, eds. Cynthia Lucia, Roy Grundmann, Art Simon, (New York, 2012): Vol 3, pp. 435–469, ISBN 978-1-4051-7984-3.

- What It Is ... What It Was!; The Black Film Explosion of the '70s in Words and Pictures by Andres Chavez, Denise Chavez, Gerald Martinez ISBN 0-7868-8377-4

- "The So Called Fall of Blaxploitation" by Ed Guerrero, The Velvet Light Trap #64 Fall 2009

References

- Lyne, William (June 20, 2018). "No Accident: From Black Power to Black Box Office". African American Review. 34 (1): 39–59. doi:10.2307/2901183. JSTOR 2901183.

- Denby, David (August 1972). "Getting Whitey". The Atlantic Monthly: 86–88.

- James, Darius (1995). That's Blaxploitation!: Roots of the Baadasssss 'Tude (Rated X by an All-Whyte Jury). ISBN 0-312-13192-5.

- Ebert, Roger (June 11, 2004). "Review of Baadasssss!". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- Canby, Vincent (April 25, 1976). "Are Black Films Losing Their Blackness?". The New York Times. p. 79. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Blaxploitation: A Sketch - Bright Lights Film Journal". March 1, 1997.

- Holden, Stephen (June 9, 2000). "FILM REVIEW; From Blaxploitation Stereotype to Man on the Street". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- "Music Genre: Blaxploitation". Allmusic. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- "African-American images on television and film". connection.ebscohost.com.

- eztha_zienne (June 29, 2016). "BaadAsssss Cinema Documentary 2002" – via YouTube.

- "Despite its incendiary name, Blaxploitation was viewed by many as being a token of empowerment". Seattle Times. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- Addison Gayle, Black World, December 1974

- Bernier, Celeste-Marie; Durkin, Hannah, eds. (2016). "Strategic Remembering and Tactical Forgetfulness in Depicting the Plantation: A Personal Account". Visualising Slavery: Art Across the African Diaspora. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-78138-267-7.

- Ball, Erica L. (November 2, 2015). "The Politics of Pain: Representing the Violence of Slavery in American Popular Culture". In Schmid, David (ed.). Violence in American Popular Culture. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4408-3206-2.

- Abrams, Simon (December 28, 2012). "5 Spaghetti Westerns & 5 Slavesploitation Films That Paved the Way for 'Django Unchained'". IndieWire. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- Gaines, Mikal J. (2005). The Black Gothic Imagination: Horror, Subjectivity, and Spectatorship from the Civil Rights Era to the New Millennium (MA thesis). College of William and Mary. p. 239. OCLC 986221383.

- Lawrence, Novotny (December 12, 2007). Blaxploitation Films of the 1970s: Blackness and Genre. London: Routledge. pp. 54–55. doi:10.4324/9780203932223. ISBN 978-0-203-93222-3.

- "Review of Die the Long Day by Orlando Patterson". Kirkus Reviews. June 26, 1972. See also Christmas, Danielle (2014). Auschwitz and the Plantation: Labor and Social Death in American Holocaust and Slavery Fiction (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Illinois at Chicago. p. 59.

- Symmons, Tom (2013). The Historical Film in the Era of New Hollywood, 1967–1980 (PhD thesis). Queen Mary University of London. p. 87.

- Wood, Robin (1998). Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-231-07605-0.

- "Beggin'". Youtube.com. November 22, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- "Michael Chabon, Telegraph Avenue: Read an exclusive excerpt". National Public Radio. August 12, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- BERNHEIMER, MARTIN (December 13, 1990). "TV REVIEW : Peter Sellars Has His Modern Way With Mozart : Opera:Conventional ideas of Baroque drama are blithely tossed aside as Figaro gets married in the Trump Tower" – via Los Angeles Times.

- Opera Nerd (January 20, 2014). "Mozart: Don Giovanni - dir. Peter Sellars (Part 1 of 3) [English Subtitles]" – via YouTube.

- Takahashi, Dean. "How developers created the story behind Mafia III and its lead character Lincoln Clay". VentureBeat. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Maynard, Richard (June 16, 2000). "The Birth and Demise of the 'Blaxploitation' Genre". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- Tom Symmons (2014): 'The Birth of Black Consciousness on the Screen'?: The African American Historical Experience, Blaxploitation, and the Production and Reception of Sounder (1972), Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, DOI: 10.1080/01439685.2014.933645

- Andrew Dawson, "Challenging Lilywhite Hollywood: African Americans and the Demand for Racial Equality in the Motion Picture Industry, 1963–1974"The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 45, No. 6, 2012

- Ed Guerrero, FRAMING BLACKNESS. Temple U. Press. pp. 95–97.

- Dutka, Elaine (June 30, 1997). "ReDiggin' the Scene". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- News from the Library of Congress: December 19, 2012 (REVISED December 20, 2012) Retrieved: 29 December 2012

- "Pam Grier looks back on blaxploitation: 'At the time some people were horrified'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- "Filmfanaddict.com review of the film". Shockingimages.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- "Five Pam Grier Classics to Stream After 'Proud Mary'". ScreenCrush.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blaxploitation. |