New Zealand English phonology

This article covers the phonological system of New Zealand English. While New Zealanders speak differently depending on their level of cultivation (i.e. the closeness to Received Pronunciation), this article covers the accent as it is spoken by educated speakers, unless otherwise noted. The IPA transcription is one designed by Bauer et al. (2007) specifically to faithfully represent a New Zealand accent, which this article follows in most aspects (see the transcription systems table below).

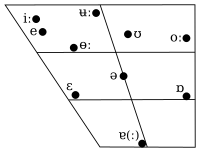

Vowels

| Lexical set | Phoneme | Phonetic realization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated | Broad | ||

| DRESS | /e/ | [e̞] | [e̝] |

| TRAP | /ɛ/ | [æ] | [ɛ̝] |

| KIT | /ə/ | [ɪ̈] | [ə] |

| COMMA | [ə] | ||

| NEAR | /iə/ | [ɪə] | [ɪə] |

| SQUARE | /eə/ | [e̞ə] | |

| FACE | /æɪ/ | [æɪ] | [ɐɪ] |

| PRICE | /ɑɪ/ | [ɑ̟ɪ] | [ɒ̝ˑɪ ~ ɔɪ] |

| GOAT | /ɐʉ/ | [ɵʊ] | [ɐʉ] |

| MOUTH | /æʊ/ | [aʊ] | [e̞ə] |

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

The vowels of New Zealand English are similar to that of other non-rhotic dialects such as Australian English and RP, but with some distinctive variations, which are indicated by the transcriptions for New Zealand vowels in the tables below:[2]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | e | iː | ʉː | ʊ | oː | |

| Mid | ɛ | ə | ɵː | ɒ | ||

| Open | ɐ | ɐː | ||||

- The original short front vowels /æ, e, ɪ/ have undergone a chain shift, which is partially reflected in their NZE transcription /ɛ, e, ə/.[3] Recent acoustic studies featuring both Australian and New Zealand voices show the accents were more similar before World War II and the short front vowels have changed considerably since then as compared to Australian English.[4] Before the shift, these vowels were pronounced close to the corresponding RP sounds. Here are the stages of the shift:[5]

- /æ/ was raised from near-open [æ] to open-mid [ɛ];

- /e/ was raised from mid [e̞] to close-mid [e];

- /ɪ/ was first centralised to [ɪ̈] and then was lowered to [ə], merging with the word-internal allophone of /ə/ as in abbot /ˈɛbət/. This effectively removes the distinction between full and reduced vowels from the dialect as it makes /ə/ a stressable vowel.

- /e/ was further raised to near-close [e̝] (the only phase not encoded in the transcription system used in this article).

- Cultivated NZE retains the open pronunciations [æ] and [e̞] and has a high central KIT ([ɪ̈]).[1]

- The difference in frontness and closeness of the KIT vowel ([ɪ̈ ~ ə] in New Zealand, [i] in Australia) has led to a long-running joke between Australians and New Zealanders whereby Australians accuse New Zealanders of saying "fush and chups" for fish and chips[3] and in turn New Zealanders accuse Australians of saying "feesh and cheeps" in light of Australia's own KIT vowel shift.[6][7][8]

- The phonemic identification of the word-final schwa as in sofa and better is problematic: phonetically, it is often as open as /ɐ/ (especially in the uterrance-final position) and speakers feel it to be an unstressed allophone of STRUT, which is how the vowel is transcribed in the article: /ˈsɐʉfɐ, ˈbetɐ/.[9][10][11] Because of that, the names of the lexical sets COMMA and LETTER are not used in this article. Instead, the mid schwa is referred to as KIT and the open one as STRUT regardless of stress and position in the word. Analyzing the word-final schwa as /ɐ/ means that the plural form sofas /ˈsɐʉfəz/ differs in two ways from the singular sofa /ˈsɐʉfɐ/; not only is there an extra /z/ consonant at the end of the word, but the a also turns into KIT because it is moved to the word-internal position. There is no such alternation in the case of the word-internal and -initial /ɐ/.

- Initial unstressed KIT is at times as open as STRUT, so that inalterable /ənˈoːltəɹəbəl/ can fall together with unalterable /ɐnˈoːltəɹəbəl/, resulting in a variable phonetic kit-strut merger. This is less common and so it is not transcribed in this article.[10][11]

- The unstressed close front vowel in happy and video is tense and so it belongs to the /iː/ phoneme: /ˈhɛpiː/, /ˈvədiːɐʉ/.[11][12][13]

- The vowel that historically corresponds to KIT in ring or in the second syllable in writing is much closer and more front than other instances of KIT and it is also associated with FLEECE by native speakers. This merger is assumed in transcriptions in this article, which is why ring and writing are transcribed /ɹiːŋ/ and /ˈɹɑɪtiːŋ/ (note that when the g is dropped, the vowel also changes: [ˈɹɑɪɾən]. Such forms are not transcribed in this article.). This makes FLEECE the only tense vowel that is permitted before /ŋ/. Some speakers also use this variant before /ɡ/ and, less often, before other consonants. As both KIT and FLEECE can occur in those environments, it must then be analyzed as an allophone of KIT. It is transcribed with a plain ⟨ə⟩ in this article and so not differentiated from other allophones of /ə/.[14]

- The NURSE vowel /ɵː/ is not only higher and/or more front than the corresponding RP vowel /ɜː/, but it is also realised with rounded lips, unlike its RP counterpart. John Wells remarks that the surname Turner /ˈtɵːnɐ/ as pronounced by a New Zealander may sound very similarly to a German word Töne /ˈtøːnə/ (meaning 'tones').[15] Possible phonetic realizations include near-close front [ʏː], near-close central [ɵ̝ː], close-mid front [øː], close-mid central [ɵː], mid front [ø̞ː] and open-mid front [œː].[16][17][18][19] It appears that realizations lower than close-mid are more prestigious than those of close-mid height and higher, so that pronunciations of the word nurse such as [nø̞ːs] and [nœːs] are less broad than [nøːs], [nɵːs] etc.[16][20] Close allophones may overlap with monophthongal realizations of /ʉː/ and there may be a potential or incipient NURSE–GOOSE merger.[20]

- The PALM/START vowel /ɐː/ in words like calm /kɐːm/, spa /spɐː/, park /pɐːk/ and farm /fɐːm/ is central or even front of central in terms of tongue position.[21] New Zealand English has the trap–bath split: words like dance /dɐːns/, chance /tʃɐːns/, plant /plɐːnt/ and grant /ɡɹɐːnt/ are pronounced with an /ɐː/ sound, as in Southern England and South Australia.[6][22] However, for many decades prior to World War II there existed an almost 50/50 split between the pronunciation of dance as /dɐːns/ or /dɛns/, plant as /plɐːnt/ or /plɛnt/, etc.[23] Can't is also pronounced /kɐːnt/ in both New Zealand and Australia and not /kɛnt/ (unlike the pronunciation found in United States and Canada). Some older Southland speakers use the TRAP vowel rather than the PALM vowel in dance, chance and castle, so that they are pronounced /dɛns, tʃɛns, ˈkɛsəl/ rather than /dɐːns, tʃɐːns, ˈkɐːsəl/.[24]

| Closing | æɪ ɑɪ oɪ æʊ ɐʉ |

|---|---|

| Centring | iə eə ʉə |

- The NEAR–SQUARE merger (of the diphthongs /iə/ and /eə/) is on the increase, especially since the beginning of the 21st century[25] so that here /hiə/ now rhymes with there /ðeə/ and beer /biə/ and bear /beə/ as well as really /ˈɹiəliː/ and rarely /ˈɹeəliː/ are homophones.[3] There is some debate as to the quality of the merged vowel, but the consensus appears to be that it is towards a close variant, [iə].[26][27]

- /ʉə/ is becoming rarer. Most speakers use either /ʉːə/ or /oː/ instead.[28]

- The phonetic quality of NZE diphthongs are as follows:

- As stated above, the starting points of /iə/ and /eə/ are identical ([ɪ]) in contemporary NZE. However, conservative speakers distinguish the two diphthongs as [ɪə] and [e̞ə].[1]

- The starting point of /ɐʉ/ is [ɐ], whereas its ending point is close to cardinal [ʉ].[26][29][30] In certain phonetic environments (especially in tonic syllables and in the word no), some speakers unround it to [ɨ], sometimes with additional fronting to [ɪ].[31]

- The fronting-closing diphthongs /æɪ, ɑɪ, oɪ/ can end close-mid [e] or close [i].[32]

- Sources do not agree on the exact phonetic realizations of certain NZE diphthongs:

- The starting point of /ʉə/ has been variously described as near-close central [ʉ̞][29] and near-close near-back [ʊ].[30]

- The ending points of /iə, eə, ʉə/ have been variously described as mid [ə][30] and open-mid [ɜ].[29]

- The starting point of /oɪ/ has been variously described as close-mid back [o][30] and mid near-back [ö̞].[29]

- The starting point of /ɑɪ/ has been variously described as near-open back [ɑ̝][30] and near-open central [ɐ].[29]

- The starting point of /æʊ/ has been variously described as varying between near-open front [æ] and open-mid front [ɛ] (with the former being more conservative)[26] and as varying between near-open front [æ] and near-open central [ɐ].[33]

- The ending point of /æʊ/ has been variously described as close central [ʉ][32] and close-mid near-back [ʊ̞].[29] According to one source, most speakers realise the ending point of /æʊ/ as mid central [ə], thus making /æʊ/ a centring diphthong akin to /iə, ʉə, eə/.[34]

Sources differ in the way they transcribe New Zealand English. The differences are listed below. The traditional phonemic orthography for the Received Pronunciation as well as the reformed phonemic orthographies for Australian and General South African English have been added for the sake of comparison.

| New Zealand English | AuE | GenSAE | RP | Example words | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This article | Wells (1982:608–609) | Bauer et al. (2007:98–100) | Hay, Maclagan & Gordon (2008:21–34) | ||||

| iː | iː | iː | i | iː | iː | iː | fleece |

| i | i | happy, video | |||||

| ə | ɘ | ɪ | ɪ | ɪ | ɪ | ring, writing | |

| ə | kit | ||||||

| ə | bit | ||||||

| ə | ə | rabbit | |||||

| ə | accept, abbot | ||||||

| ɐ | sofa, better | ||||||

| ʌ | ɐ | ʌ | ɐ | ɐ | ʌ | strut, unknown | |

| ɐː | aː | ɐː | a | ɐː | ɑː | ɑː | palm, start |

| iə | iə | iə | iə | ɪə | ɪə | ɪə | near |

| ʊ | ʊ | ʊ | ʊ | ʊ | ɵ | ʊ | foot |

| ʉː | uː | ʉː | u | ʉː | ʉː | uː | goose |

| ʉə | ʊə | ʉə | ʊə | ʉːə | ʉə | ʊə | cure |

| ʉː | fury | ||||||

| oː | ɔː | oː | sure | ||||

| oː | ɔ | oː | ɔː | thought, north | |||

| e | e | e | e | e | e | e | dress |

| ɵː | ɜː | ɵː | ɜ | ɜː | øː | ɜː | nurse |

| ɛ | æ | ɛ | æ | æ | æ | æ | trap |

| ɒ | ɒ | ɒ | ɒ | ɔ | ɒ | ɒ | lot |

| æɪ | ʌɪ | æe | ei | æɪ | eɪ | eɪ | face |

| eə | eə | eə | eə | eː | eː | eə | square |

| ɐʉ | ʌʊ | ɐʉ | oʊ | əʉ | œɨ | əʊ | goat |

| oɪ | ɔɪ | oe | ɔi | oɪ | ɔɪ | ɔɪ | choice |

| ɑɪ | ɑɪ | ɑe | ai | ɑɪ | aɪ | aɪ | price |

| æʊ | æʊ | æo | aʊ | æɔ | aɤ | aʊ | mouth |

Conditioned mergers

- Before /l/, the vowels /iː/ and /iə/ (as in reel /ɹiːl/ vs real /ɹiəl/, the only minimal pair), as well as /ɒ/ and /ɐʉ/ (doll /dɒl/ vs dole /dɐʉl/, and sometimes /ʊ/ and /ʉː/ (pull /pʊl/ vs pool /pʉːl/), /e/ and /ɛ/ (Ellen /ˈelən/ vs Alan /ˈɛlən/) and /ʊ/ and /ə/ (full /fʊl/ vs fill /fəl/) may be merged.[22][35]

Consonants

- New Zealand English is mostly non-rhotic (with linking and intrusive R), except for speakers with the so-called Southland burr, a semi-rhotic, Scottish-influenced dialect heard principally in Southland and parts of Otago.[36][37] Older Southland speakers use /ɹ/ variably after vowels, but today younger speakers use /ɹ/ only with the NURSE vowel and occasionally with the LETTER vowel. Younger Southland speakers pronounce /ɹ/ in third term /ˌθɵːɹd ˈtɵːɹm/ (General NZE pronunciation: /ˌθɵːd ˈtɵːm/) but sometimes in farm cart /fɐːm kɐːt/ (same as in General NZE).[38] The rhotic Southern New Zealand accent was depicted in The World's Fastest Indian, a movie about the life of New Zealander Burt Munro and his achievements at Bonneville Speedway. On the DVD release of the movie one of the Special Features is Roger Donaldson's original 1971 documentary Offerings to the God of Speed featuring the real Burt Monro.[39] His (and others) southern New Zealand accent is definitive. Among r-less speakers, however, non-prevocalic /ɹ/ is sometimes pronounced in a few words, including Ireland /ˈɑɪɹlənd/, merely /ˈmiəɹliː/, err /ɵːɹ/, and the name of the letter R /ɐːɹ/ (General NZE pronunciations: /ˈɑɪlənd, ˈmiəliː, ɵː, ɐː/).[40] Like most white New Zealand speakers, some Māori speakers are semi-rhotic, although it is not clearly identified to any particular region or attributed to any defined language shift. The Māori language itself tends in most cases to use an r with an alveolar tap [ɾ], like Scottish dialect.[41]

- /l/ is velarised ("dark") in all positions, and is often vocalised in syllable codas so that ball is pronounced as [boːʊ̯] or [boːə̯].[42][6] Even when not vocalised, it is darker in codas than in onsets, possibly with pharyngealisation.[43] Vocalisation varies in different regions and between different socioeconomic groups; the younger, lower social class speakers vocalise /l/ most of the time.[8]

- Many younger speakers have the wine–whine merger, which means that the traditional distinction between the /w/ and /hw/ phonemes no longer exists for them. All speakers are more likely to retain it in lexical words than in grammatical ones, therefore even older speakers have a variable merger here.[44][45][46]

- As with Australian English and American English the intervocalic /t/ may be flapped, so that the sentence "use a little bit of butter" may be pronounced [jʉːz ɐ ˈləɾo bəɾ əv ˈbɐɾɐ] (phonemically /jʉːz ɐ ˈlətəl bət əv ˈbɐtɐ/).[44] Evidence for this usage exists as far back as the early 19th century, such as Kerikeri being transliterated as "Kiddee Kiddee" by missionaries.[47]

Other features

- Some New Zealanders pronounce past participles such as grown /ˈɡɹɐʉən/, thrown /ˈθɹɐʉən/ and mown /ˈmɐʉən/ with two syllables, the latter containing a schwa /ə/ not found in other accents. By contrast, groan /ɡɹɐʉn/, throne /θɹɐʉn/ and moan /mɐʉn/ are all unaffected, meaning these word pairs can be distinguished by ear.[8]

- The trans- prefix is usually pronounced /tɹɛns/. This produces mixed pronunciation of the as in words like transplant /ˈtɹɛnsplɐːnt/. However, /tɹɐːns/ is also heard, typically in older New Zealanders.

- The name of the letter H is almost always /æɪtʃ/, as in North American, and is almost never aspirated (/hæɪtʃ/).

- The name of the letter Z is usually the British, Canadian and Australian zed /zed/. However the alphabet song for children is sometimes sung ending with /ziː/ in accordance with the rhyme. Where Z is universally pronounced zee in places, names, terms, or titles, such as ZZ Top, LZ (landing zone), Jay Z (celebrity), or Z Nation (TV show) New Zealanders follow universal pronunciation.

- The word foyer is usually pronounced /ˈfoɪɐ/, as in Australian and American English, rather than /ˈfoɪæɪ/ as in British English.

- The word with is almost always pronounced /wəð/, though /wəθ/ may be found in some minority groups.

- The word and combining form graph is pronounced both /ɡɹɐːf/ and /ɡɹɛf/.

- The word data is commonly pronounced /ˈdɐːtɐ/, with /ˈdæɪtɐ/ being the second commonest, and /ˈdɛtɐ/ being very rare.

- Words such as contribute and distribute are predominantly pronounced with the stress on the second syllable (/kənˈtɹəbjʉːt/, /dəˈstɹəbjʉːt/). Variants with the stress on the first syllable (/ˈkɒntɹəbjʉːt/, /ˈdəstɹəbjʉːt/) also occur.

Pronunciation of Māori place names

The pronunciations of many Māori place names were anglicised for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but since the 1980s increased consciousness of the Māori language has led to a shift towards using a Māori pronunciation. The anglicisations have persisted most among residents of the towns in question, so it has become something of a shibboleth, with correct Māori pronunciation marking someone as non-local.

| Placename | English pronunciation | Te Reo Māori | Māori pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cape Reinga | /ˌkæɪp ɹiːˈɛŋɐ/ | re-i-nga | [ˈɾɛːiŋɐ] |

| Hawera | /ˈhɐːweɹɐ, -wəɹ-, -ɐː/ | ha-we-ra | [ˈhɑːwɛɾɐ] |

| Otahuhu | /ˌɐʉtəˈhʉːhʉː/ | o-ta-hu-hu | [ɔːˈtɑːhʉhʉ] |

| Otorohanga | /ˌɐʉtɹəˈhɐŋɐ, -ˈhɒŋɐ/ | o-to-ra-ha-nga | [ˈɔːtɔɾɔhɐŋɐ] |

| Paraparaumu | /ˌpɛɹəpɛˈɹæʊmʉː/ | pa-ra-pa-rau-mu | [pɐɾɐpɐˈɾaumʉ] |

| Taumarunui | /ˌtæʊməɹəˈnʉːiː/ | tau-ma-ra-nu-i | [ˈtaumɐɾɐnʉi] |

| Te Awamutu | /ˌtiː əˈmʉːtʉː/ | te a-wa-mu-tu | [tɛ ɐwɐˈmʉtʉ] |

| Te Kauwhata | /ˌtiː kəˈhwɒtɐ/ | te kau-fa-ta | [tɛ ˈkauɸɐtɐ] |

| Waikouaiti | /ˈwɛkəwɑɪt, -wɒt/ | wai-kou-ai-ti | [ˈwɐikɔuˌɑːiti] |

Some anglicised names are colloquially shortened, for example, Coke /kɐʉk/ for Kohukohu, the Rapa /ˈɹɛpɐ/ for the Wairarapa, Kura /ˈkʉəɹɐ/ for Papakura, Papatoe /ˈpɛpətɐʉiː/ for Papatoetoe, Otahu /ˌɐʉtəˈhʉː/ for Otahuhu, Paraparam /ˈpɛɹəpɛɹɛm/ or Pram /pɹɛm/ for Paraparaumu, the Naki /ˈnɛkiː/ for Taranaki, Cow-cop /ˈkæʊkɒp/ for Kaukapakapa and Pie-cock /ˈpɑɪkɒk/ for Paekakariki.

There is some confusion between these shortenings, especially in the southern South Island, and the natural variations of the southern dialect of Māori. Not only does this dialect sometimes feature apocope, but consonants also vary slightly from standard Māori. To compound matters, names were often initially transcribed by Scottish settlers, rather than the predominantly English settlers of other parts of the country; as such further alterations are not uncommon. Thus, while Lake Wakatipu is sometimes referred to as Wakatip, Oamaru as Om-a-roo ![]() /ˌɒməˈɹʉː/ and Waiwera South as Wy-vra /ˈwɑɪvɹɐ/, these differences may be as much caused by dialect differences – either in Māori or in the English used during transcription – as by the process of anglicisation. An extreme example is The Kilmog /ˈkəlmɒɡ/, the name of which is cognate with the standard Māori Kirimoko.[48]

/ˌɒməˈɹʉː/ and Waiwera South as Wy-vra /ˈwɑɪvɹɐ/, these differences may be as much caused by dialect differences – either in Māori or in the English used during transcription – as by the process of anglicisation. An extreme example is The Kilmog /ˈkəlmɒɡ/, the name of which is cognate with the standard Māori Kirimoko.[48]

References

- Gordon & Maclagan (2004), p. 609.

- Bauer et al. (2007), pp. 98–100.

- "Simon Bridges has the accent of New Zealand's future. Get used to it". NZ Herald. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Evans, Zoë; Watson, Catherine I. (2004). "An acoustic comparison of Australian and New Zealand English vowel change". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.119.6227. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hay, Maclagan & Gordon (2008), pp. 41–42.

- Crystal (2003), p. 354.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), p. 587.

- Gordon & Maclagan (2004), p. 611.

- Wells (1982), p. 606.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), pp. 585, 587.

- Bauer et al. (2007), p. 101.

- Wells (1982), pp. 606–607.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), pp. 584–585.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), pp. 587–588.

- Wells (1982), pp. 607–608.

- Wells (1982), p. 607.

- Roca & Johnson (1999), p. 188.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), pp. 582, 591.

- Bauer et al. (2007), p. 98.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), p. 591.

- "3. – Speech and accent – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 2013-09-05. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- Trudgill & Hannah (2008), p. 29.

- The New Zealand accent: a clue to New Zealand identity? Pages 47-48 arts.canterbury.ac.nz

- "5. – Speech and accent – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 2013-09-05. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- "4. Stickmen, New Zealand's pool movie – Speech and accent – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 2013-09-05. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), pp. 582, 592.

- Gordon & Maclagan (2004), p. 610.

- Gordon et al. (2004), p. 29.

- Bauer et al. (2007), p. 99.

- Hay, Maclagan & Gordon (2008), p. 26.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), p. 592.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), p. 582.

- Bauer et al. (2007), pp. 98–99.

- Hay, Maclagan & Gordon (2008), p. 25.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), p. 589.

- "Other forms of variation in New Zealand English". Te Kete Ipurangi. Ministry of Education. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- Gordon & Maclagan (2004), p. 605.

- "5. – Speech and accent – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 2013-09-05. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- "The World's Fastest Indian: Anthony Hopkins, Diane Ladd, Iain Rea, Tessa Mitchell, Aaron Murphy, Tim Shadbolt, Annie Whittle, Greg Johnson, Antony Starr, Kate Sullivan, Craig Hall, Jim Bowman, Roger Donaldson, Barrie M. Osborne, Charles Hannah, Don Schain, Gary Hannam, John J. Kelly, Masaharu Inaba: Movies & TV". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), p. 594.

- Hogg, R.M., Blake, N.F., Burchfield, R., Lass, R., and Romaine, S., (eds.) (1992) The Cambridge history of the English language. (Volume 5) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521264785 p. 387. Retrieved from Google Books.

- Trudgill & Hannah (2008), p. 31.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), p. 595.

- Trudgill & Hannah (2008), p. 30.

- Gordon & Maclagan (2004), pp. 606, 609.

- Bauer et al. (2007), p. 97.

- "Earliest New Zealand: The Journals and Correspondence of the Rev. John Butler, Chapter X". New Zealand Electronic Text Centre. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- Goodall, M., & Griffiths, G. (1980) Maori Dunedin. Dunedin: Otago Heritage Books. p. 45: This hill [The Kilmog]...has a much debated name, but its origins are clear to Kaitahu and the word illustrates several major features of the southern dialect. First we must restore the truncated final vowel (in this case to both parts of the name, 'kilimogo'). Then substitute r for l, k for g, to obtain the northern pronunciation, 'kirimoko'.... Though final vowels existed in Kaitahu dialect, the elision was so nearly complete that pākehā recorders often omitted them entirely.

Bibliography

- Bauer, Laurie; Warren, Paul (2004), "New Zealand English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 580–602, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Bauer, Laurie; Warren, Paul; Bardsley, Dianne; Kennedy, Marianna; Major, George (2007), "New Zealand English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37 (1): 97–102, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002830

- Crystal, David (2003), The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press

- Gordon, Elizabeth; Maclagan, Margaret (2004), "Regional and social differences in New Zealand: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 603–613, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Gordon, Elizabeth; Campbell, Lyle; Hay, Jennifer; Maclagan, Margaret; Sudbury, Peter; Trudgill, Andrea, eds. (2004), New Zealand English: Its Origins and Evolution, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Hay, Jennifer; Maclagan, Margaret; Gordon, Elizabeth (2008), New Zealand English, Dialects of English, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-2529-1

- Roca, Iggy; Johnson, Wyn (1999), A Course in Phonology, Blackwell Publishing

- Trudgill, Peter; Hannah, Jean (2008), International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English (5th ed.), London: Arnold

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Volume 3: Beyond the British Isles (pp. i–xx, 467–674). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52128541-0.

Further reading

- Bauer, Laurie (1994), "8: English in New Zealand", in Burchfield, Robert (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language, 5: English in Britain and Overseas: Origins and Development, Cambridge University Press, pp. 382–429, ISBN 0-521-26478-2

- Bauer, Laurie (2015), "Australian and New Zealand English", in Reed, Marnie; Levis, John M. (eds.), The Handbook of English Pronunciation, Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 269–285, ISBN 978-1-118-31447-0

- Warren, Paul; Bauer, Laurie (2004), "Maori English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 614–624, ISBN 3-11-017532-0