Ukrainian phonology

This article deals with the phonology of the standard Ukrainian language.

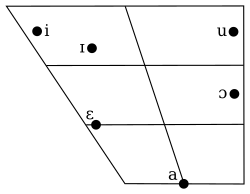

Vowels

Ukrainian has six vowel phonemes: /i, u, ɪ, ɛ, ɔ, ɑ/.

/ɪ/ may be classified as a retracted high-mid front vowel,[1] transcribed in narrow IPA as [e̠], [ë], [ɪ̞] or [ɘ̟].

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɪ | u |

| Mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | ɑ |

Ukrainian has no phonemic distinction between long and short vowels; however, unstressed vowels are somewhat reduced in time and, as a result, in quality.[2]

- In unstressed position /ɑ/ has an allophone [ɐ].[3]

- Unstressed /ɔ/ has an allophone [o] that slightly approaches /u/ if it is followed by a syllable with /u/ or /i/.[3]

- Unstressed /u/ has an allophone [ʊ].[3]

- Unstressed /ɛ/ and /ɪ/ approach [e] that may or may not be a common allophone for the two phonemes.[3]

- /i/ has no notable variation in unstressed position.[3]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard | Soft | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | ||||

| Stop | p b | t d | tʲ dʲ | k ɡ | |||

| Affricate | t͡s d͡z | t͡sʲ d͡zʲ | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | ||||

| Fricative | f | s z | sʲ zʲ | ʃ ʒ | x | ɦ | |

| Approximant | ʋ~w | l | lʲ | j | |||

| Trill | r | rʲ | |||||

In the table above, if there are two consonants in a row, the one to the right is voiced, and the one to the left is voiceless.

Phonetic details:

- There is no complete agreement about the phonetic nature of /ɦ/. According to some linguists, it is pharyngeal [ʕ][4] ([ħ] [or sometimes [x] in weak positions] when devoiced).[4] According to others, it is glottal [ɦ].[5][6][7]

- Word-finally, /m/, /l/, /r/ are voiceless [m̥], [l̥], [r̥] after voiceless consonants.[8] In case of /r/, it only happens after /t/.[9]

- /w/ is most commonly bilabial [β̞] before vowels but can alternate with labiodental [ʋ] (most commonly before /i/),[10] and can be a true labiovelar [w] before /ɔ/ or /u/.[3] It is also vocalized to [u̯] before a consonant at the beginning of a word, after a vowel before a consonant or after a vowel at the end of a word.[10][11] If /w/ occurs before a voiceless consonant and not after a vowel, the voiceless articulation [ʍ] is also possible.[3]

- /r/ often becomes a single tap [ɾ] in the spoken language.

- /t, d, dʲ, n, nʲ, s, sʲ, z, zʲ, t͡s, t͡sʲ, d͡z, d͡zʲ/ are dental [t̪, d̪, d̪ʲ, n̪, n̪ʲ, s̪, s̪ʲ, z̪, z̪ʲ, t̪͡s̪, t̪͡s̪ʲ, d̪͡z̪, d̪͡z̪ʲ],[12] while /tʲ, l, lʲ, r, rʲ/ are alveolar [tʲ, l, lʲ, r, rʲ].[13]

- The group of palatalized consonants consists of 10 phonemes: /j, dʲ, zʲ, lʲ, nʲ, rʲ, sʲ, tʲ, t͡sʲ, d͡zʲ/. All except /j/ have a soft and a hard variant. There is no agreement about the nature of the palatalization of /rʲ/; sometimes, it is considered as a semi-palatalized consonant.[14] Labial consonants /p, b, m, f/ have just semi-palatalized versions, and /w/ has only the hard variant.[15] The palatalization of the consonants /ɦ, ɡ, ʒ, k, x, t͡ʃ, ʃ, d͡ʒ/ is weak; they are usually treated rather as the allophones of the respective hard consonants, not as separate phonemes.[16]

- Unlike Russian and several other Slavic languages, Ukrainian does not have final devoicing for most obstruents, as can be seen, for example, in віз "cart", which is pronounced

[ˈʋiz] , not *[ˈʋis].[3]

[ˈʋiz] , not *[ˈʋis].[3] - The fricative articulations [v, ɣ] are voiced allophones of /f, x/ respectively if they are voiced before other voiced consonants. (See #Consonant assimilation.) /x, ɦ/ do not form a perfect voiceless-voiced phoneme pair, but their allophones may overlap if /ɦ/ is devoiced to [x] (rather than [h]). In the standard language, /f, w/ do not form a voiceless-voiced phoneme pair at all, as [v] does not phonemically overlap with /w/, and [ʍ] (voiceless allophone of /w/) does not phonemically overlap with /f/.[3]

When two or more consonants occur word-finally, a vowel is epenthesized under the following conditions:[17] Given a consonantal grouping C1(ь)C2(ь), C being any consonant. The vowel is inserted between the two consonants and after the ь. A vowel is not inserted unless C2 is either /k/, /w/, /l/, /m/, /r/, or /t͡s/. Then:

- If C1 is /w/, /ɦ/, /k/, or /x/, the epenthisized vowel is always [o]

- No vowel is epenthesized if the /w/ is derived from a Common Slavic vocalic *l, for example, /wɔwk/ (see below)

- If C2 is /l/, /m/, /r/, or /t͡s/, then the vowel is /ɛ/.

- The combinations, /-stw/ /-sk/ are not broken up.

- If the C1 is /j/ (й), the above rules may apply. However, both forms (with and without the fill vowel) often exist.

Alternation of vowels and semivowels

The semivowels /j/ and /w/ alternate with the vowels /i/ and /u/ respectively. The semivowels are used in syllable codas: after a vowel and before a consonant, either within a word or between words:

- він іде́ /ˈwin iˈdɛ/ ('he's coming')

- вона́ йде /wɔˈnɑ ˈjdɛ/ ('she's coming')

- він і вона́ /ˈwin i wɔˈnɑ/ ('he and she')

- вона́ й він /wɔˈnɑ j ˈwin/ ('she and he');

- Утоми́вся вже /utɔˈmɪwsʲɑ ˈwʒɛ/ ('already gotten tired')

- Уже́ втоми́вся /uˈʒɛ wtɔˈmɪwsʲɑ/ ('already gotten tired')

- Він утоми́вся. /ˈwin utɔmɪwsʲɑ/ ('He's gotten tired.')

- Він у ха́ті. /ˈwin u ˈxɑt⁽ʲ⁾i/ ('He's inside the house.')

- Вона́ в ха́ті. /wɔˈnɑ w ˈxɑt⁽ʲ⁾i/ ('She's inside the house.')

- підучи́ти /piduˈt͡ʃɪtɪ/ ('to learn/teach (a little more)')

- ви́вчити /ˈwɪwt͡ʃɪtɪ/ ('to have learnt')

That feature distinguishes Ukrainian phonology remarkably from Russian and Polish, two related languages with many cognates.

Consonant assimilation

There is no word-final or assimilatory devoicing in Ukrainian. There is, however, assimilatory voicing: voiceless obstruents are voiced when preceding voiced obstruents. (But the reverse is not true, and sonorants do not trigger voicing.)[18]

- наш [nɑʃ] ('our')

- наш дід [nɑʒ ˈd⁽ʲ⁾id] ('our grandfather')

- бере́за [bɛˈrɛzɑ] ('birch')

- бері́зка [bɛˈr⁽ʲ⁾izkɑ] ('small birch')

The exceptions are легко, вогко, нігті, кігті, дьогтю, дігтяр, and derivatives: /ɦ/ may then be devoiced to [h] or even merge with /x/.[3]

Unpalatalized dental consonants /n, t, d, t͡s, d͡z, s, z, r, l/ become palatalized if they are followed by other palatalized dental consonants /nʲ, tʲ, dʲ, t͡sʲ, d͡zʲ, sʲ, zʲ, rʲ, lʲ/. They are also typically palatalized before the vowel /i/. Historically, contrasting unpalatalized and palatalized articulations of consonants before /i/ were possible and more common, with the absence of palatalization usually reflecting that regular sound changes in the language made an /i/ vowel actually evolve from an older, non-palatalizing /ɔ/ vowel. Ukrainian grammar still allows for /i/ to alternate with either /ɛ/ or /ɔ/ in the regular inflection of certain words. The absence of consonant palatalization before /i/ has become rare, however, but is still allowed.[3]

While the labial consonants /m, p, b, f, w/ cannot be phonemically palatalized, they can still precede one of the iotating vowels є і ьо ю я, when many speakers replace the would-be sequences *|mʲ, pʲ, bʲ, fʲ, wʲ| with the consonant clusters /mj, pj, bj, fj, wj/, a habit also common in nearby Polish.[3] The separation of labial consonant from /j/ is already hard-coded in many Ukrainian words (and written as such with an apostrophe), such as in В'ячеслав /wjɑt͡ʃɛˈslɑw/ "Vyacheslav", ім'я /iˈmjɑ/ "name" and п'ять /pjɑtʲ/ "five". The combinations of labials with iotating vowels are written without the apostrophe after consonants in the same morpheme, e. g. свято /ˈsʲw(j)ɑto/ "holiday", цвях "nail" (but зв'язок "union", where з- is a prefix), and in some loanwords, e. g. бюро "bureau".

Dental sibilant consonants /t͡s, d͡z, s, z/ become palatalized before any of the labial consonants /m, p, b, f, w/ followed by one of the iotating vowels є і ьо ю я, but the labial consonants themselves cannot retain phonemic palatalization. Thus, words like свято /ˈsʲw(j)ɑto/ "holiday" and сват /swɑt/ "matchmaker" retain their separate pronunciations (whether or not an actual /j/ is articulated).[3]

Sibilant consonants (including affricates) in clusters assimilate with the place of articulation and palatalization state of the last segment in a cluster. The most common case of such assimilation is the verbal ending -шся in which |ʃsʲɑ| assimilates into /sʲːɑ/.[3]

Dental plosives /t, tʲ, d, dʲ/ assimilate to affricate articulations before coronal affricates or fricatives /t͡s, d͡z, s, z, t͡sʲ, d͡zʲ, sʲ, zʲ, t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ, ʃ, ʒ/ and assume the latter consonant's place of articulation and palatalization. If the sequences |t.t͡s, d.d͡z, t.t͡sʲ, d.d͡zʲ, t.t͡ʃ, d.d͡ʒ| regressively assimilate to */t͡s.t͡s, d͡z.d͡z, t͡sʲ.t͡sʲ, d͡zʲ.d͡zʲ, t͡ʃ.t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ.d͡ʒ/, they gain geminate articulations /t͡sː, d͡zː, t͡sʲː, d͡zʲː, t͡ʃː, d͡ʒː/.[3]

Deviations of spoken language

There are some typical deviations which may appear in spoken language (often under the influence of Russian);[19] usually they are considered as phonetic errors by pedagogists.[20]

- [ɨ] for /ɪ/

- [t͡ɕ] for /t͡ʃ/ and [ɕt͡ɕ] or even [ɕː] for [ʃt͡ʃ]

- [rʲ] for /r/, [bʲ] for /b/, [vʲ] for /w/ (Ха́рків, Об, любо́в’ю)

- [v] or [f] (the latter in syllable-final position) for [w ~ u̯ ~ β̞ ~ ʋ ~ ʍ] (любо́в, роби́в, вари́ти, вода́),[10] in effect also turning /f, w/ into a true voiceless-voiced phoneme pair, which is not the case in the standard language

- Final-obstruent devoicing

Historical phonology

Modern standard Ukrainian descends from Common Slavic and is characterized by a number of sound changes and morphological developments, many of which are shared with other East Slavic languages. These include:

- In a newly closed syllable, that is, a syllable that ends in a consonant, Common Slavic *o and *e mutated into /i/ if the following vowel was one of the yers (*ŭ or *ĭ).

- Pleophony: The Common Slavic combinations, *CoRC and *CeRC, where R is either *r or *l, become in Ukrainian:

- The Common Slavic nasal vowel *ę is reflected as /jɑ/; a preceding labial consonant generally was not palatalized after this, and after a postalveolar it became /ɑ/. Examples: Common Slavic *pętĭ became Ukrainian /pjɑtʲ/ (п’ять); Common Slavic *telę became Ukrainian /tɛˈlʲɑ/ (теля́); and Common Slavic *kurĭčę became Ukrainian /kurˈt͡ʃɑ/ (курча́).

- Common Slavic *ě (Cyrillic ѣ), generally became Ukrainian /i/ except:

- word-initially, where it became /ji/: Common Slavic *(j)ěsti became Ukrainian ї́сти /ˈjistɪ/

- after the postalveolar sibilants where it became /ɑ/: Common Slavic *ležěti became Ukrainian /lɛˈʒɑtɪ/ (лежа́ти)

- Common Slavic *i and *y are both reflected in Ukrainian as /ɪ/

- The Common Slavic combination -CĭjV, where V is any vowel, became -CʲːV, except:

- if C is labial or /r/ where it became -CjV

- if V is the Common Slavic *e, then the vowel in Ukrainian mutated to /ɑ/, e.g., Common Slavic *žitĭje became Ukrainian /ʒɪˈtʲːɑ/ (життя́)

- if V is Common Slavic *ĭ, then the combination became /ɛj/, e.g., genitive plural in Common Slavic *myšĭjĭ became Ukrainian /mɪˈʃɛj/ (мише́й)

- if one or more consonants precede C then there is no doubling of the consonants in Ukrainian

- Sometime around the early thirteenth century, the voiced velar stop lenited to [ɣ] (except in the cluster *zg).[21] Within a century, /ɡ/ was reintroduced from Western European loanwords and, around the sixteenth century, [ɣ] debuccalized to [ɦ].[22]

- Common Slavic combinations *dl and *tl were simplified to /l/, for example, Common Slavic *mydlo became Ukrainian /ˈmɪlɔ/ (ми́ло).

- Common Slavic *ǔl and *ĭl became /ɔw/. For example, Common Slavic *vĭlkǔ became /wɔwk/ (вовк) in Ukrainian.

Notes

- Rusanivs’kyj, Taranenko & Zjabljuk (2004:104)

- Rusanivs’kyj, Taranenko & Zjabljuk (2004:407)

- Buk, Mačutek & Rovenchak (2008)

- Danyenko & Vakulenko (1995:12)

- Pugh & Press (2005:23)

- The sound is described as "laryngeal fricative consonant" (гортанний щілинний приголосний) in the official orthography: '§ 14. Letter H' in Український правопис, Kyiv: Naukova dumka, 2012, p. 19 (see e-text)

- Українська мова: енциклопедія, Kyiv, 2000, p. 85.

- Danyenko & Vakulenko (1995:6, 8)

- Danyenko & Vakulenko (1995:8)

- Žovtobrjux & Kulyk (1965:121–122)

- Rusanivs’kyj, Taranenko & Zjabljuk (2004:522–523)

- Danyenko & Vakulenko (1995:8–10)

- Danyenko & Vakulenko (1995:8 and 10)

- Ponomariv (2001:16, 20)

- Ponomariv (2001:14–15)

- Buk, Mačutek & Rovenchak (2008)

- Carlton (1972:?)

- Mascaró & Wetzels (2001:209)

- Oleksandr Ponomariv. Культура слова: мовностилістичні поради

- Vitalij Marhalyk. Проблеми орфоепії в молодіжних телепрограмах

- Shevelov (1977:145)

- Shevelov (1977:148)

References

- Bilous, Tonia (2005), Українська мова засобами Міжнародного фонетичного алфавіту [Ukrainian in International Phonetic alphabet] (DOC)

- Buk, Solomija; Mačutek, Ján; Rovenchak, Andrij (2008), Some properties of the Ukrainian writing system, arXiv:0802.4198, Bibcode:2008arXiv0802.4198B

- Carlton, T.R. (1972), A Guide to the Declension of Nouns in Ukrainian, Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta Press

- Danyenko, Andrii; Vakulenko, Serhii (1995), Ukrainian, Lincom Europa, ISBN 978-3-929075-08-3

- Mascaró, Joan; Wetzels, W. Leo (2001). "The Typology of Voicing and Devoicing". Language. 77 (2): 207–244. doi:10.1353/lan.2001.0123.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pohribnyj, M.I., ed. (1986), Орфоепічний словни, Kiev: Radjans’ka škola

- Pompino-Marschall, Bernd; Steriopolo, Elena; Żygis, Marzena (2016), "Ukrainian", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 47 (3): 349–357, doi:10.1017/S0025100316000372

- Ponomariv, O.D., ed. (2001), Сучасна українська мова: Підручник, Kyiv: Lybid’

- Pugh, Stefan; Press, Ian (2005) [First published 1999], Ukrainian: A Comprehensive Grammar, London: Routledge

- Rusanivs’kyj, V. M.; Taranenko, O. O.; Zjabljuk, M. P.; et al. (2004). Українська мова: Енциклопедія. ISBN 978-966-7492-19-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shevelov, George Y. (1977). "On the Chronology of h and the New g in Ukrainian" (PDF). Harvard Ukrainian Studies. Cambridge: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. 1 (2): 137–152.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shevelov, George Y. (1993), "Ukrainian", in Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville (eds.), The Slavonic Languages, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 947–998

- Žovtobrjux, M.A., ed. (1973), Українська літературна вимова і наголос: Словник - довідник, Kiev: Nakova dumka

- Žovtobrjux, M.A.; Kulyk, B.M. (1965). Курс сучасної української літературної мови. Частина I. Kiev: Radjans’ka škola.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bahmut, Alla Josypivna (1980). Інтонація як засіб мовної комунікації. Kiev: Naukova dumka.

- Toc’ka, N.I. (1973). Голосні фонеми української літературної мови. Kiev: Kyjivs’kyj universytet.

- Toc’ka, N.I. (1995). Сучасна українська літературна мова. Kiev: Vyšča škola.

- Zilyns'kyj, I. (1979). A Phonetic Description of the Ukrainian Language. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-66612-7.

- Zygis, Marzena (2003), "Phonetic and Phonological Aspects of Slavic Sibilant Fricatives" (PDF), ZAS Papers in Linguistics, 3: 175–213, archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-11, retrieved 2020-08-21