Dot-com bubble

The dot-com bubble (also known as the dot-com boom,[1] the tech bubble,[2] and the Internet bubble) was a stock market bubble caused by excessive speculation of Internet-related companies in the late 1990s, a period of massive growth in the use and adoption of the Internet.[2][3]

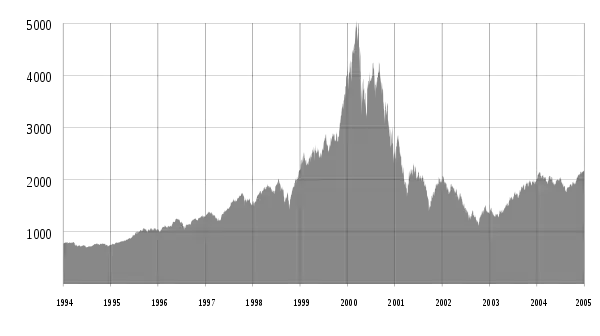

Between 1995 and its peak in March 2000, the Nasdaq Composite stock market index rose 400%, only to fall 78% from its peak by October 2002, giving up all its gains during the bubble. During the crash, many online shopping companies, such as Pets.com, Webvan, and Boo.com, as well as several communication companies, such as Worldcom, NorthPoint Communications, and Global Crossing, failed and shut down.[4][5] Some companies, such as Cisco, whose stock declined by 86%,[5] Amazon.com, and Qualcomm, lost a large portion of their market capitalization but survived.

Prelude to the bubble

The 1993 release of Mosaic and subsequent web browsers gave computer users access to the World Wide Web, greatly popularizing use of the Internet.[6] Internet use increased as a result of the reduction of the "digital divide" and advances in connectivity, uses of the Internet, and computer education. Between 1990 and 1997, the percentage of households in the United States owning computers increased from 15% to 35% as computer ownership progressed from a luxury to a necessity.[7] This marked the shift to the Information Age, an economy based on information technology, and many new companies were founded.

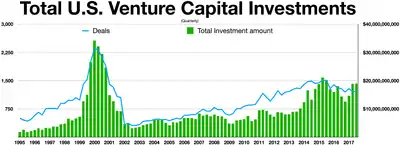

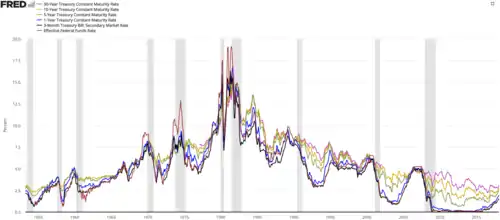

At the same time, a decline in interest rates increased the availability of capital.[8] The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, which lowered the top marginal capital gains tax in the United States, also made people more willing to make more speculative investments.[9] Alan Greenspan, then-Chair of the Federal Reserve, allegedly fueled investments in the stock market by putting a positive spin on stock valuations.[10] The Telecommunications Act of 1996 was expected to result in many new technologies from which many people wanted to profit.[11]

The bubble

As a result of these factors, many investors were eager to invest, at any valuation, in any dot-com company, especially if it had one of the Internet-related prefixes or a ".com" suffix in its name. Venture capital was easy to raise. Investment banks, which profited significantly from initial public offerings (IPO), fueled speculation and encouraged investment in technology.[12] A combination of rapidly increasing stock prices in the quaternary sector of the economy and confidence that the companies would turn future profits created an environment in which many investors were willing to overlook traditional metrics, such as the price–earnings ratio, and base confidence on technological advancements, leading to a stock market bubble.[10] Between 1995 and 2000, the Nasdaq Composite stock market index rose 400%. It reached a price–earnings ratio of 200, dwarfing the peak price–earnings ratio of 80 for the Japanese Nikkei 225 during the Japanese asset price bubble of 1991.[10] In 1999, shares of Qualcomm rose in value by 2,619%, 12 other large-cap stocks each rose over 1,000% in value, and seven additional large-cap stocks each rose over 900% in value. Even though the Nasdaq Composite rose 85.6% and the S&P 500 Index rose 19.5% in 1999, more stocks fell in value than rose in value as investors sold stocks in slower growing companies to invest in Internet stocks.[13]

An unprecedented amount of personal investing occurred during the boom and stories of people quitting their jobs to trade on the financial market were common.[14] The news media took advantage of the public's desire to invest in the stock market; an article in The Wall Street Journal suggested that investors "re-think" the "quaint idea" of profits, and CNBC reported on the stock market with the same level of suspense as many networks provided to the broadcasting of sports events.[10][15]

At the height of the boom, it was possible for a promising dot-com company to become a public company via an IPO and raise a substantial amount of money even if it had never made a profit—or, in some cases, realized any material revenue. People who received employee stock options became instant paper millionaires when their companies executed IPOs; however, most employees were barred from selling shares immediately due to lock-up periods.[12] The most successful entrepreneurs, such as Mark Cuban, sold their shares or entered into hedges to protect their gains.

Spending tendencies of dot-com companies

Most dot-com companies incurred net operating losses as they spent heavily on advertising and promotions to harness network effects to build market share or mind share as fast as possible, using the mottos "get big fast" and "get large or get lost". These companies offered their services or products for free or at a discount with the expectation that they could build enough brand awareness to charge profitable rates for their services in the future.[16][17]

The "growth over profits" mentality and the aura of "new economy" invincibility led some companies to engage in lavish spending on elaborate business facilities and luxury vacations for employees. Upon the launch of a new product or website, a company would organize an expensive event called a dot com party.[18][19]

Bubble in telecom

The bubble in telecom was called "the biggest and fastest rise and fall in business history".[20]

Partially a result of greed and excessive optimism, especially about the growth of data traffic fueled by the rise of the Internet, in the five years after the Telecommunications Act of 1996 went into effect, telecommunications equipment companies invested more than $500 billion, mostly financed with debt, into laying fiber optic cable, adding new switches, and building wireless networks.[11] In many areas, such as the Dulles Technology Corridor in Virginia, governments funded technology infrastructure and created favorable business and tax law to encourage companies to expand.[21] The growth in capacity vastly outstripped the growth in demand.[11] Spectrum auctions for 3G in the United Kingdom in April 2000, led by Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown, raised £22.5 billion.[22] In Germany, in August 2000, the auctions raised £30 billion.[23][24] A 3G spectrum auction in the United States in 1999 had to be re-run when the winners defaulted on their bids of $4 billion. The re-auction netted 10% of the original sales prices.[25][26] When financing became hard to find as the bubble burst, the high debt ratios of these companies led to bankruptcy.[27] Bond investors recovered just over 20% of their investments.[28] However, several telecom executives sold stock before the crash including Philip Anschutz, who reaped $1.9 billion, Joseph Nacchio, who reaped $248 million, and Gary Winnick, who sold $748 million worth of shares.[29]

Bursting of the bubble

On January 31, 1999, a total of two dot-com companies had purchased ad spots for Super Bowl XXXIII.[30]

Around the turn of the millennium, spending on technology was volatile as companies prepared for the Year 2000 problem. There were concerns that computer systems would have trouble changing their clock and calendar systems from 1999 to 2000 which might trigger wider social or economic problems, but there was virtually no impact or disruption due to adequate preparation.

On January 10, 2000, America Online, led by Steve Case and Ted Leonsis, announced a merger with Time Warner, led by Gerald M. Levin. The merger was the largest to date and was questioned by many analysts.[31]

On January 30, 2000, almost 20 percent [12 ads] of the 61 ads for Super Bowl XXXIV were purchased by dot-coms (however this estimate ranges from 12-19 companies depending on the source and the context in which the term "dot-com" company implies). At that time, the cost for a 30-second commercial cost between $1.9 million and $2.2 million.[32][33]

In February 2000, with the Year 2000 problem no longer a worry, Alan Greenspan announced plans to aggressively raise interest rates, which led to significant stock market volatility as analysts disagreed as to whether or not technology companies would be affected by higher borrowing costs.

On Friday March 10, 2000, the NASDAQ Composite stock market index peaked at 5,048.62.[34]

On March 13, 2000, news that Japan had once again entered a recession triggered a global sell off that disproportionately affected technology stocks.[35]

On March 15, 2000, Yahoo! and eBay ended merger talks and the Nasdaq fell 2.6%, but the S&P 500 Index rose 2.4% as investors shifted from strong performing technology stocks to poor performing established stocks.[36]

On March 20, 2000, Barron's featured a cover article titled "Burning Up; Warning: Internet companies are running out of cash—fast", which predicted the imminent bankruptcy of many Internet companies.[37] This led many people to rethink their investments. That same day, MicroStrategy announced a revenue restatement due to aggressive accounting practices. Its stock price, which had risen from $7 per share to as high as $333 per share in a year, fell $140 per share, or 62%, in a day.[38] The next day, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates, leading to an inverted yield curve, although stocks rallied temporarily.[39]

On April 3, 2000, judge Thomas Penfield Jackson issued his conclusions of law in the case of United States v. Microsoft Corp. (2001) and ruled that Microsoft was guilty of monopolization and tying in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. This led to a one-day 15% decline in the value of shares in Microsoft and a 350-point, or 8%, drop in the value of the Nasdaq. Many people saw the legal actions as bad for technology in general.[40] That same day, Bloomberg News published a widely read article that stated: "It's time, at last, to pay attention to the numbers".[41]

On Friday, April 14, 2000, the Nasdaq Composite index fell 9%, ending a week in which it fell 25%. Investors were forced to sell stocks ahead of Tax Day, the due date to pay taxes on gains realized in the previous year.[42]

By June 2000, dot-com companies were forced to rethink their advertising campaigns.[43]

On November 9, 2000, Pets.com, a much-hyped company that had backing from Amazon.com, went out of business only nine months after completing its IPO.[44][45] By that time, most Internet stocks had declined in value by 75% from their highs, wiping out $1.755 trillion in value.[46]

In January 2001, just three dot-com companies bought advertising spots during Super Bowl XXXV.[47] The September 11 attacks accelerated the stock-market drop later that year.[48]

Investor confidence was further eroded by several accounting scandals and the resulting bankruptcies, including the Enron scandal in October 2001, the WorldCom scandal in June 2002,[49] and the Adelphia Communications Corporation scandal in July 2002.

By the end of the stock market downturn of 2002, stocks had lost $5 trillion in market capitalization since the peak.[50] At its trough on October 9, 2002, the NASDAQ-100 had dropped to 1,114, down 78% from its peak.[51][52]

Aftermath

After venture capital was no longer available, the operational mentality of executives and investors completely changed. A dot-com company's lifespan was measured by its burn rate, the rate at which it spent its existing capital. Many dot-com companies ran out of capital and went through liquidation. Supporting industries, such as advertising and shipping, scaled back their operations as demand for services fell. However, many companies were able to endure the crash; 48% of dot-com companies survived through 2004, albeit at lower valuations.[16]

Several companies and their executives, including Bernard Ebbers, Jeffrey Skilling, and Kenneth Lay, were accused or convicted of fraud for misusing shareholders' money, and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission levied large fines against investment firms including Citigroup and Merrill Lynch for misleading investors.

After suffering losses, retail investors transitioned their investment portfolios to more cautious positions.[53] Popular Internet forums that focused on high tech stocks, such as Silicon Investor, RagingBull.com, Yahoo! Finance, and The Motley Fool declined in use significantly.[54]

Investor Sir John Templeton successfully shorted the dot-com bubble, betting many trendy NASDAQ technology stocks would drop in value.[55] He did so by accurately predicting mass sales of stock at the end of legally-required six-month holding periods for company insiders after Initial Public Offerings. Templeton believed most insiders knew their company stock was highly overvalued and wanted to cash out while prices were high, while mass sales of stock would drive prices lower.

Job market and office equipment glut

Layoffs of programmers resulted in a general glut in the job market. University enrollment for computer-related degrees dropped noticeably.[56][57] Anecdotes of unemployed programmers going back to school to become accountants or lawyers were common.

Aeron chairs, which retailed for $1,100 each and were the symbol of the opulent office furniture of dot-com companies, were liquidated en masse.[58]

Legacy

As growth in the technology sector stabilized, companies consolidated; some, such as Amazon.com, eBay, and Google gained market share and came to dominate their respective fields. The most valuable public companies are now generally in the technology sector.

In a 2015 book, venture capitalist Fred Wilson, who funded many dot-com companies and lost 90% of his net worth when the bubble burst, said about the dot-com bubble:

A friend of mine has a great line. He says "Nothing important has ever been built without irrational exuberance." Meaning that you need some of this mania to cause investors to open up their pocketbooks and finance the building of the railroads or the automobile or aerospace industry or whatever. And in this case, much of the capital invested was lost, but also much of it was invested in a very high throughput backbone for the Internet, and lots of software that works, and databases and server structure. All that stuff has allowed what we have today, which has changed all our lives... that's what all this speculative mania built.[59]

Notable companies

A Dot-com company is a for-profit company that does most of its business through the Internet, and that usually uses a .com TLD. Below are some Dot-com companies founded with venture capital during the bubble, spun off by larger companies as Dot-com companies, or whose success or failure was determined by the bubble.

- 3Com: Shares soared after announcing the corporate spin-off of Palm, Inc.

- 360networks: A fiber optic company that had a market capitalization of over $13 billion but filed for bankruptcy a few months later.

- AboveNet: Its stock rose 32% on the day it announced a stock split.

- Actua Corporation (formerly Internet Capital Group): A company that invested in B2B e-commerce companies, it reached a market capitalization of almost $60 billion at the height of the bubble, making Ken Fox, Walter Buckley, and Pete Musser billionaires on paper.

- Airspan Networks: A wireless firm; in July 2000, its stock price doubled on its first day of trading as investors focused on telecommunications companies instead of dot-com companies.[60]

- Akamai Technologies: Its stock price rose over 400% on its first day of trading in October 1999.

- AltaVista: A Web search engine established in 1995. It became one of the most-used early search engines, but lost ground to Google and was purchased by Yahoo! in 2003.

- Alteon WebSystems: Its shares soared 294% on its first day of trading.

- Blucora (then InfoSpace): Founded by Naveen Jain, at its peak its market cap was $31 billion and was the largest Internet business in the American Northwest. In March 2000, its stock reached a price $1,305 per share, but by 2002 the price had declined to $2 a share.[61]

- Blue Coat Systems (formerly CacheFlow): Its stock price rose over 400% on its first day of trading in November 1999.

- Boo.com: An online clothing retailer, it spent $188 million in just six months. It filed for bankruptcy in May 2000.[62]

- Books-A-Million: A book retailer whose stock price soared from around $3 per share on November 25, 1998, to $38.94 on November 27, 1998, and an intra-day high of $47.00 on November 30, 1998 after it announced an updated website. Two weeks later, the share price was back down to $10. By 2000, the share price had returned to $3.[63]

- Broadband Sports: A network of sports-content websites that raised over $60 million before going bust in February 2001.[64]

- Broadcast.com: A streaming media website that was acquired by Yahoo! for $5.9 billion in stock, making Mark Cuban and Todd Wagner multi-billionaires. The site is now defunct.[65]

- CDNow: Founded by Jason Olim and his brother, it was an online retailer of compact discs and music-related products that reached a valuation of over $1 billion in April 1998. In 2000, it was acquired by Bertelsmann Music Group for $117 million and was later shut down.

- Chemdex.com: A company founded by David Perry that operated an online marketplace for businesses, it reached a market capitalization of over $7 billion despite minimal revenues.

- Cobalt Networks: Its stock price rose over 400% on its first day of trading; acquired by Sun Microsystems for $2 billion in December 2000.

- Commerce One: A business-to-business software company that reached a valuation of $21 billion despite minimal revenue.[66]

- Covad: Shares rose fivefold within months of its IPO.

- Cyberian Outpost: One of the first successful online shopping websites, it reached a peak market capitalization of $1 billion. It used controversial marketing campaigns including a Super Bowl ad in which fake gerbils were shot out of a cannon. It was acquired by Fry's Electronics in 2001 for $21 million, including the assumption of $13 million in debt.[67]

- CyberRebate: Promised customers a 100% rebate after purchasing products priced at as much as 10 times the retail cost. It went bankrupt in 2001 and stopped paying rebates.[68]

- Digex: one of the first Internet service providers in the United States, its stock price rose to $184 per share; the company was acquired for $1 per share a few years later.[69]

- Digital Insight: Its shares soared 114% on its first day of trading.

- Divine: Founded by Andrew Filipowski, it was modeled after CMGI. It went public as the bubble burst and filed for bankruptcy after executives were accused of looting a subsidiary.

- DoubleClick: An online advertising company that soared after its IPO, it was acquired by Google in 2007.

- eGain: Its stock price doubled shortly after its 1999 IPO.

- Egghead Software: An online software retailer, its shares surged in 1998 as investors bought up shares of Internet companies; by 2001, the company was bankrupt.

- eToys.com: An online toy retailer whose stock price hit a high of $84.35 per share in October 1999. In February 2001, it filed for bankruptcy with $247 million in debt. It was acquired by KB Toys, which later also filed for bankruptcy.[70]

- Excite: A web portal founded by Joe Kraus and others that merged with Internet service provider @Home Network in 1999 to become Excite@Home, promising to be the "AOL of broadband". After trying unsuccessfully to sell the Excite portal during a sharp downturn in online advertising, the company filed for bankruptcy in September 2001.[71] It was acquired by Ask.com in March 2004.[72]

- Flooz.com: A digital currency founded by Robert Levitan; it folded in 2001 due to lack of consumer acceptance. It was famous for having Whoopi Goldberg as its spokesperson.[73]

- Forcepoint (formerly Websense): It held an IPO at the peak of the bubble.

- Freei: Filed for bankruptcy in October 2000, soon after canceling its IPO. At the time, it was the 5th largest Internet service provider in the United States, with 3.2 million users.[74] Famous for its mascot, Baby Bob, the company lost $19 million in 1999 on revenues of less than $1 million.[75]

- Gadzoox: A storage area network company, its shares tripled on its first day of trading giving it a market capitalization of $1.97 billion; the company was sold 4 years later for $5.3 million.

- Geeknet (formerly VA Linux): A provider of built-to-order Intel personal computer systems based on Linux and other open source projects, it set the record for largest first-day price gain upon its IPO on December 9, 1999; after the stock priced at $30/share, it ended the first day of trading at $239.25/share, a 698% gain, making founder Larry Augustin a billionaire on paper.[76]

- GeoCities: Founded by David Bohnett, it was acquired by Yahoo! for $3.57 billion in January 1999[77] and was shut down in 2009.[78]

- Global Crossing: A telecommunications company founded in 1997; it reached a market capitalization of $47 billion in February 2000 before filing bankruptcy in January 2002.[79]

- theGlobe.com: A social networking service that launched in April 1995 and made headlines when its November 1998 IPO resulted in the largest first day gain of any IPO to date. CEO Stephan Paternot became a visible symbol of the excesses of dot-com millionaires and is famous for saying "Got the girl. Got the money. Now I'm ready to live a disgusting, frivolous life".[80]

- govWorks: Founded by fraudster Kaleil Isaza Tuzman; it was featured in the documentary film Startup.com.[81]

- Handspring: A PDA maker that was defunct by 2003, when it was purchased by Palm Inc.

- Healtheon: Founded by James H. Clark, merged with WebMD in 1999 with a stock swap valued at $7.9 billion[82] but eventually shut down.

- HomeGrocer: A public online grocer that merged with Webvan.

- Infoseek: Founded by Steve Kirsch, it was acquired by Disney in 1999; it was valued at $7 billion but eventually shut down.

- inktomi: Founded by Eric Brewer, it reached a valuation of $25 billion in March 2000; acquired by Yahoo! in 2003 for $241 million.[83]

- Interactive Intelligence: A telecommunications software company whose stock doubled on its first day of trading.

- Internet America: Its stock price doubled in a day in December 1999 despite no specific news about the company.

- iVillage: On its first day of trading in March 1999, its stock rose 255% to $84 per share.[84] It was acquired by NBC for $8.50 per share in 2006 and shut down.

- iWon: Backed by CBS, it gave away $1 million to a lucky contestant each month and $10 million in April 2000 on a half-hour special program that was broadcast on CBS.[85]

- Kozmo.com: Founded by Joseph Park, it offered one-hour local delivery of several items with no delivery fees from March 1998 until it went bust in April 2001.[86]

- Lastminute.com: Founded by Martha Lane Fox and Brent Hoberman, its IPO in the United Kingdom on March 14, 2000, coincided with the bursting of the bubble.[87] Shares placed initially at 380p sharply rose to 511p, but had collapsed to below 190p by the first week of April 2000.[88]

- The Learning Company (formerly SoftKey): Owned by Kevin O'Leary, it was acquired by Mattel in 1999 for $3.5 billion and sold a year later for $27.3 million.[89]

- Liquid Audio: Despite its stock doubling in value on its first day of trading in July 1999, its technology was obsolete by 2004.

- LookSmart: Founded by Evan Thornley, its value rose from $23 million to $5 billion within months, but it lost 99% of its value as the bubble burst.

- Lycos: Founded by Michael Loren Mauldin, under the leadership of Bob Davis, it was acquired by Terra Networks for $12.5 billion in May 2000.[90] It was sold in 2004 to Seoul, South Korea-based Daum Communications Corporation for $95.4 million.[91]

- MarchFirst: A web development company formed on March 1, 2000, by the merger of USWeb and CKS Group, it filed forbankruptcy and liquidation just over a year after it was formed.

- MicroStrategy: After rising from $7 to as high as $333 in a year, its shares lost $140, or 62%, on March 20, 2000, following the announcement of a financial restatement for the previous two years by founder Michael J. Saylor.[38]

- Net2Phone: A VoIP provider founded by Howard Jonas whose stock price soared after its 1999 IPO.[92]

- NetBank: A direct bank, its stock price per share fluctuated between $3.50 and $83 in 1999.[93]

- Netscape: After a popular IPO, it was acquired by AOL in 1999 for $4.2 billion in stock.

- Network Solutions: A domain name registrar led by Jim Rutt, it was acquired by Verisign for $21 billion in March 2000, at the peak of the bubble.

- NorthPoint Communications: Agreed to a significant investment by Verizon and a merger of DSL businesses in September 2000; however, Verizon backed out 2 months later after NorthPoint was forced to restate its financial statements, including a 20% reduction in revenue, after its customers failed to pay as the bubble burst. NorthPoint then filed for bankruptcy. After lawsuits from both parties, Verizon and NorthPoint settled out of court.[94]

- Palm, Inc.: Spun off from 3Com at the peak of the bubble, its shares plunged as the bubble burst.

- Pets.com: Led by Julie Wainwright, it sold pet supplies to retail customers before filing for bankruptcy in 2000.[44]

- PFSweb: A B2B company whose stock price doubled after its IPO.

- Pixelon: Streaming video company that hosted a $16 million dot com party in October 1999 in Las Vegas with celebrities including Chely Wright, LeAnn Rimes, Faith Hill, Dixie Chicks, Sugar Ray, Natalie Cole, KISS, Tony Bennett, The Brian Setzer Orchestra, and a reunion of The Who. The company failed less than a year later when it became apparent that its technologies were fraudulent or misrepresented. Its founder had been a convicted felon who changed his name.

- PLX Technology: Shares rose fivefold within months of its IPO.

- Prodigy: An ISP whose stock price doubled on its first day of trading.

- Pseudo.com: One of the first live streaming video websites, it produced its own content in a studio in SoHo, Manhattan and streamed up to seven hours of live programming a day on its website.[95]

- Radvision: A videotelephony company, its stock price rose 150% on its first day of trading.

- Razorfish: An Internet advertising consultancy, its stock doubled on its first day of trading in April 1999.[96]

- Redback Networks: A telecommunications equipment company, its stock soared 266% in its first day of trading, giving it a market capitalization of $1.77 billion.[97]

- Register.com: A domain name registrar, its stock soared after its IPO in March 2000, at the peak of the bubble.

- Ritmoteca.com: One of the first online music stores selling music on a pay-per-download basis and an early predecessor to the iTunes business model. It pioneered digital distribution deals as one of the first companies to sign agreements with major music publishers.[98]

- Startups.com: "Ultimate dot-com startup" that went out of business in 2002.[99]

- Steel Connect (formerly CMGI Inc.): a company that invested in many Internet startups; between 1995 and 1999, its stock appreciated 4,921%, but declined 99% when the bubble burst.[100]

- Savvis: A fiber optic company.

- Terra Networks: A web portal and Internet access provider in the US, Spain and Ibero-America. After its November 1999 IPO, its shares skyrocketed from an initial price of €11 to €158 in just three months. The price then sunk under €3 in a matter of weeks. In February 2005, the company was acquired by Telefónica.

- Think Tools: One of the most extreme symptoms of the bubble in Europe, this company reached a market valuation of CHF2.5 billion in March 2000 despite no prospects of having a product.[99]

- TIBCO Software: Its stock price rose tenfold shortly after its 1999 IPO.

- Tradex Technologies: A B2B e-commerce company, it was sold for $5.6 billion at the height of the bubble, making Daniel Aegerter a billionaire on paper.

- Transmeta: A semiconductor designer that attempted to challenge Intel, its IPO in November 2000 was the last successful technology IPO until the IPO of Google in 2004. The company shut down in 2009 after failing to execute.

- uBid: An online auction site founded in 1997 as a subsidiary of PCM, Inc. that went public in December 1998 at $15 per share before its stock price soared to $186 per share, a market value of $1.5 billion.

- United Online: An ISP formed by the merger of NetZero and Juno Online Services as the bubble burst.

- Usinternetworking Inc: Its stock price rose 174% on its first day of trading.

- UUNET: One of the largest Internet service providers, its stock price soared after its 1995 IPO; it was acquired in 1996.

- Verio: A web hosting provider, it was acquired for $5 billion at the peak of the bubble.

- VerticalNet: A host of 43 business-to-business (B2B) procurement portals that was valued at $1.6 billion after its IPO, despite having only $3.6 million in quarterly revenue.[101]

- Vignette Corporation: Its stock rose 1,500% within months after its IPO.

- WebChat Broadcasting System: the largest and most popular online chat, interactive and event network with around 3 million registered users, it was purchased by Infoseek in April 1998 for approximately $6.7 million; Go.com acquired Infoseek later in 1998, and closed WebChat in September 1999.

- Webvan: An online grocer that promised delivery within 30 minutes; it went bankrupt in 2001 after $396 million of venture capital funding and an IPO that raised $375 million and was folded into Amazon.com.[102]

- World Online: a Netherlands-based Internet service provider, it became a public company on March 17, 2000 at a €12 billion valuation, the largest IPO on the Euronext Amsterdam, and the largest European Internet company IPO.

- Yahoo!: A company that, under the leadership of Timothy Koogle, Jerry Yang, and David Filo acquired several companies for billions of dollars in stock, only to shut them down a few years later.

See also

Internet portal

Internet portal Economics portal

Economics portal 1990s portal

1990s portal

References

- Edwards, Jim (December 6, 2016). "One of the kings of the '90s dot-com bubble now faces 20 years in prison". Business Insider. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- "More Money Than Anyone Imagined". The Atlantic. July 26, 2019. Archived from the original on October 12, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Here's Why The Dot Com Bubble Began And Why It Popped". Business Insider. December 15, 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-04-06.

- "The greatest defunct Web sites and dotcom disasters". CNET. June 5, 2008. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Kumar, Rajesh (December 5, 2015). Valuation: Theories and Concepts. Elsevier. p. 25.

- Kline, Greg (April 20, 2003). "Mosaic started Web rush, Internet boom". The News-Gazette. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Issues in labor Statistics" (PDF). U.S. Department of Labor. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-12. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- Weinberger, Matt (February 3, 2016). "If you're too young to remember the insanity of the dot-com bubble, check out these pictures". Business Insider. Archived from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Here's Why The Dot Com Bubble Began And Why It Popped". Business Insider. December 15, 2010. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Teeter, Preston; Sandberg, Jorgen (2017). "Cracking the enigma of asset bubbles with narratives". Strategic Organization. 15 (1): 91–99. doi:10.1177/1476127016629880.

- Litan, Robert E. (December 1, 2002). "The Telecommunications Crash: What To Do Now?". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Smith, Andrew (2012). Totally Wired: On the Trail of the Great Dotcom Swindle. Bloomsbury Books. ISBN 978-1-84737-449-3. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- Norris, Floyd (January 3, 2000). "THE YEAR IN THE MARKETS; 1999: Extraordinary Winners and More Losers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- Kadlec, Daniel (August 9, 1999). "Day Trading: It's a Brutal World". Time. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Lowenstein, Roger (2004). Origins of the Crash: The Great Bubble and Its Undoing. Penguin Books. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-59420-003-8.

- BERLIN, LESLIE (November 21, 2008). "Lessons of Survival, From the Dot-Com Attic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- Dodge, John (May 16, 2000). "MotherNature.com's CEO Defends Dot-Coms' Get-Big-Fast Strategy". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- Cave, Damien (April 25, 2000). "Dot-com party madness". Salon. Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- HuffStutter, P.J. (December 25, 2000). "Dot-Com Parties Dry Up". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "The great telecoms crash". The Economist. July 18, 2002. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Donnelly, Sally B.; Zagorin, Adam (August 14, 2000). "D.C. Dotcom". Time. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "UK mobile phone auction nets billions". BBC News. April 27, 2000. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Osborn, Andrew (November 17, 2000). "Consumers pay the price in 3G auction". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- "German phone auction ends". CNN. August 17, 2000. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Keegan, Victor (April 13, 2000). "Dial-a-fortune". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Sukumar, R. (April 11, 2012). "Policy lessons from the 3G failure". Mint. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- White, Dominic (December 30, 2002). "Telecoms crash 'like the South Sea Bubble'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Hunn, David; Eaton, Collin (September 12, 2016). "Oil bust on par with telecom crash of dot-com era". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- "Inside the Telecom Game". Bloomberg Businessweek. August 5, 2002. Archived from the original on 2020-06-07. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- Beer, Jeff (2020-01-20). "20 years ago, the dot-coms took over the Super Bowl". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 2020-03-02. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- Johnson, Tom (January 10, 2000). "Thats AOL folks". CNN. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Pender, Kathleen (September 13, 2000). "Dot-Com Super Bowl Advertisers Fumble / But Down Under, LifeMinders.com may win at Olympics". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- Kircher, Madison Malone (February 3, 2019). "Revisiting the Ads From 2000's 'Dot-Com Super Bowl'". New York. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- Long, Tony (March 10, 2010). "March 10, 2000: Pop Goes the Nasdaq!". Wired. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- "Nasdaq tumbles on Japan". CNN. March 13, 2000. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "Dow wows Wall Street". CNN. March 15, 2000. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Willoughby, Jack (March 10, 2010). "Burning Up; Warning: Internet companies are running out of cash—fast". Barron's. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "MicroStrategy plummets". CNN. March 20, 2000. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "Wall St.: What rate hike?". CNN. March 21, 2000. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "Nasdaq sinks 350 points". CNN. April 3, 2000. Archived from the original on August 11, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Yang, Catherine (April 3, 2000). "Commentary: Earth To Dot Com Accountants". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- "Bleak Friday on Wall Street". CNN. April 14, 2000. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Owens, Jennifer (June 19, 2000). "IQ News: Dot-Coms Re-Evaluate Ad Spending Habits". AdWeek. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- "Pets.com at its tail end". CNN. November 7, 2000. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "The Pets.com Phenomenon". MSNBC. October 19, 2016. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Kleinbard, David (November 9, 2000). "The $1.7 trillion dot.com lesson". CNN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Elliott, Stuart (January 8, 2001). "In Super Commercial Bowl XXXV, the not-coms are beating the dot-coms". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "World markets shatter". CNN. September 11, 2001. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Beltran, Luisa (July 22, 2002). "WorldCom files largest bankruptcy ever". CNN. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Gaither, Chris; Chmielewski, Dawn C. (July 16, 2006). "Fears of Dot-Com Crash, Version 2.0". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Glassman, James K. (February 11, 2015). "3 Lessons for Investors From the Tech Bubble". Kiplinger's Personal Finance. Archived from the original on 2020-04-04. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- Alden, Chris (March 10, 2005). "Looking back on the crash". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Reuteman, Rob (August 9, 2010). "Hard Times Investing: For Some, Cash Is Everything And Only Thing". CNBC. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Forster, Stacy (January 31, 2001). "Raging Bull Goes for a Bargain As Interest in Stock Chat Wanes". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- Lauren Templeton and Scott Phillips (2008). Investing the Templeton Way: The Market-Beating Strategies of Value Investing's Legendary Bargain Hunter. McGraw Hill Education

- desJardins, Marie (October 22, 2015). "The real reason U.S. students lag behind in computer science". Fortune. Archived from the original on March 7, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Mann, Amar; Nunes, Tony (2009). "After the Dot-Com Bubble: Silicon Valley High-Tech Employment And Wages in 2001 and 2008". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Archived from the original on 2018-11-16. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- Kennedy, Brian (September 15, 2006). "Remembering the Dot-Com Throne". New York. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Donnelly, Jacob (February 14, 2016). "Here's what the future of bitcoin looks like—and it's bright". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- "Airspan soars in debut". CNN. July 20, 2000. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Heath, David; Chan, Sharon Pian (March 6, 2005). "Dot-con job: How InfoSpace took its investors for a ride". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on March 15, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Sorkin, Andrew Ross (June 2, 2000). "Fashionmall.com Swoops In for the Boo.com Fire Sale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "CNNfn market movers". CNN. November 25, 1998. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "Online sports network shutters sites". CNET. February 16, 2001. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Forbes: Broadcast.com". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2018-01-30. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- Hamm, Steve (February 3, 2003). "Online Extra: From Hot to Scorched at Commerce One". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 2017-05-16. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- Flynn, Laurie J. (July 24, 2001). "As Cyberian Outpost plunges toward the abyss, two suitors wait patiently to pick up the pieces". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Livingston, Brian (May 18, 2001). "Millions vaporized in CyberRebate collapse". CNET. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Handley, John (2005). Telebomb. Amacom. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- "10 big dot.com flops—eToys.com". CNN. March 10, 2010. Archived from the original on December 8, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Teather, David (October 1, 2001). "Excite files for bankruptcy with $1bn debt". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- "Ask Jeeves extends Excite deal". CNET. May 20, 2005. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Jane, Martinson (August 28, 2001). "Flooz.com expires after suffering $300,000 sting". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Internet Provider Freei Networks Files for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy". The Wall Street Journal. October 9, 2000. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Freeinternet.com Scores User Surge". QuinStreet. August 11, 2000. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- "VA Linux rockets on debut". CNN. December 9, 1999. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "Yahoo! buys GeoCities". CNN. January 28, 1999. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Shaer, Matthew (October 26, 2009). "GeoCities, a relic of a different web era, shuttered by Yahoo". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Global Crossing Chapter 11 Petition" (PDF). PacerMonitor. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- Helmore, Edward (May 9, 2001). "So Who's Crying Over Spilt Milk?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- Adler, Carlye (July 1, 2000). "Too Much, Too Soon GovWorks had the big idea and an all-star board but still bungled it up. What's the lesson? Don't offend potential customers". Fortune. CNN. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "Healtheon, WebMD to merge". CNN. May 20, 1999. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Yahoo to buy search-software maker Inktomi". USA Today. December 23, 2002. Archived from the original on 2017-04-15. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- "iVillage IPO takes off". CNN. March 19, 1999. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "iWon.com Awards Arthur 'Ti' Moyer III $1 Million!" (Press release). PR Newswire. March 15, 2009. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Kempe, Peter (March 31, 2001). "The Day the Wheels Fell off Kozmo.com". Fast Company. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Jeffery, Simon (March 14, 1998). "lastminute flotation soars ahead". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Cellan-Jones, Rory (2001). Dot.Bomb: The Rise and Fall of Dot.com Britain. The Quarto Group. ISBN 978-1854107909. Archived from the original on 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- Goldman, Abigail (December 6, 2002). "Mattel Settles Shareholders Lawsuit For $122 Million". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Lycos in $12.5B deal". CNN. May 16, 2000. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "South Korean Company Buys Lycos". Wired. August 4, 2004. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Net2Phone Shares Gain 77% After $81 Million Offering". The Wall Street Journal. July 30, 1999. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Molis, Jim (October 11, 1999). "Net bank stocks buckle down for the long haul". American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on July 3, 2003. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- "Verizon Agrees to Settle NorthPoint Merger Suits". Los Angeles Times. Bloomberg News. July 24, 2002. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Blair, Jayson (January 25, 2001). "Remains of Pseudo.com Bought for Fraction of What It Spent". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- "WHERE ARE THEY NOW? The Kings Of The '90s Dot-Com Bubble". Business Insider. October 18, 2013. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Redback Networks Soars 266% On Its First Day of Trading". The Wall Street Journal. May 18, 1999. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- Sutter, Mary (December 19, 2000). "Latin music site inks Sony distribution deal". Variety. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- Evans, Sean (October 18, 2012). "The 50 Worst Internet Startup Fails of All Time". Complex. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "CMGI Can Defy Gravity Only So Long". The New York Times. December 10, 2000. Archived from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- "Land grab". Forbes. June 23, 1999. Archived from the original on May 16, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- Richtel, Matt (November 6, 1999). "Webvan Stock Price Closes 65% Above Initial Offering". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

Further reading

- Abramson, Bruce (2005). Digital Phoenix; Why the Information Economy Collapsed and How it Will Rise Again. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-51196-4.

- Aharon, David Y.; Gavious, Ilanit; Yosef, Rami (2010). "Stock market bubble effects on mergers and acquisitions". The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 50 (4): 456–70. doi:10.1016/j.qref.2010.05.002.

- Cassidy, John (2009). Dot.con: How America Lost Its Mind and Its Money in the Internet Era. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780061841781.

- Cellan-Jones, Rory (2001). Dot.Bomb: The Rise and Fall of Dot.com Britain. Aurum. ISBN 978-1854107909.

- Daisey, Mike (2014). Twenty-one Dog Years: Doing Time at Amazon.com. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-2580-9.

- Goldfarb, Brent D.; Kirsch, David; Miller, David A. (April 24, 2006). "Was There Too Little Entry During the Dot Com Era?". Robert H. Smith School Research Paper (RHS 06-029). SSRN 899100.

- Kindleberger, Charles P. (2005). Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780230365353.

- Kuo, David (2001). dot.bomb: My Days and Nights at an Internet Goliath. ISBN 978-0-316-60005-7.

- Lowenstein, Roger (2004). Origins of the Crash: The Great Bubble and Its Undoing. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-59420-003-8.

- Wolff, Michael (1999). Burn Rate: How I Survived the Gold Rush Years on the Internet. Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 9780752826066. Burn Rate at Google Books.