Nianfo

Nianfo (Chinese: 念佛; pinyin: niànfó, Japanese: 念仏 (ねんぶつ, nenbutsu), Korean: 염불; RR: yeombul, Vietnamese: niệm Phật) is a term commonly seen in Pure Land Buddhism. In the context of Pure Land practice, it generally refers to the repetition of the name of Amitābha. It is a translation of Sanskrit buddhānusmṛti (or, "recollection of the Buddha"[1]).

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

Indian Sanskrit Nianfo

The Sanskrit phrase used in India is not mentioned originally in the bodies of the two main Pure Land sutras. It appears in the opening of the extant Sanskrit Infinite Life Sutra, as well as the Contemplation Sutra, although it is a reverse rendering from Chinese, as the following:

- namo'mitābhāya buddhaya [2]

The apostrophe and omission of the first "A" in "Amitābha" comes from normal Sanskrit sandhi transformation, and implies that the first "A" is omitted. A more accessible rendering might be:

- Namo Amitābhāya Buddhaya

A literal English translation would be "Hail Buddha of Infinite Light". The Sanskrit word-by-word pronunciation is the following;

- [nɐmoːɐmɪtaːbʱaːjɐ]

While almost unknown, and unused outside of the original Sanskrit, the texts provide a recitation of Amitābha's alternate aspect of Amitāyus as;

- namo'mitāyuṣe buddhaya [2]

Again, a more accessible rendering might be;

- Namo Amitāyuṣe Buddhaya

A literal translation of this version would be "Hail Buddha of Infinite Life".

Nianfo in various forms

As the practice of nianfo spread from India to various other regions, the original pronunciation changed to fit various native languages.

| Language | As written | Romanization |

|---|---|---|

| Sanskrit | नमोऽमिताभाय बुद्धय

नमोऽमितयुसे बुद्धय |

Namo'mitābhāya Buddhaya

Namo'mitāyuṣe Buddhaya |

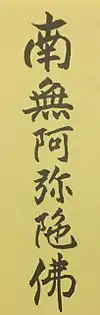

| Chinese | Traditional: 南無阿彌陀佛 Simplified: 南无阿弥陀佛 |

Mandarin: Nāmó Ēmítuófó/Nāmó Āmítuófó[3] Cantonese: naa1 mo4 o1 mei4 to4 fat6 |

| Japanese | Kanji: 南無阿弥陀仏 Hiragana: なむ あみだ ぶつ |

Namu Amida Butsu |

| Korean | Hanja: 南無阿彌陀佛 Hangul: 나무아미타불 |

Namu Amita Bul |

| Vietnamese | Quốc ngữ: Nam mô A-di-đà Phật Chữ nôm: 南無阿彌陀佛 |

Nam mô A-di-đà Phật |

In China, the practice of nianfo was codified with the establishment of the separate Pure Land school of Buddhism. The most common form of this is the six syllable nianfo; some shorten it into Ēmítuófó/Āmítuófó.[4] In the Japanese Jodo Shinshu sect, it is often shortened to na man da bu.

Nianfo variants

In the Jodo Shinshu tradition in Japan, variant forms of the nianfo have been used since its inception. The founder, Shinran, used a nine-character Kujimyōgō (九字名号) in the Shoshinge and the Sanamidabutsuge (讃阿弥陀佛偈) hymns:

南無不可思議光如来

Na mu fu ka shi gi kō nyo rai

"I take refuge in the Buddha of Inconceivable Light!"

Further, the "restorer" of Jodo Shinshu, Rennyo, frequently inscribed the nianfo for followers using a 10-character Jūjimyōgō (十字名号):

帰命尽十方無碍光如来

Ki myō jin jip-pō mu ge kō nyo rai"I take refuge in the Tathagata of Unobstructed Light Suffusing the Ten Directions".

The latter was originally popularized by Shinran's descendant (and Rennyo's ancestor), Kakunyo, but its use was greatly expanded by Rennyo.

Purpose of Nianfo

Regarding Pure Land practice in Indian Buddhism, Hajime Nakamura writes that as described in the Pure Land sūtras from India, Mindfulness of the Buddha (Skt. buddhānusmṛti, Ch. nianfo) is the essential practice.[5] These forms of mindfulness are essentially methods of meditating upon Amitābha Buddha.[5]

In the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, the bodhisattva Mahāsthāmaprāpta tells how the practice of nianfo enabled him to obtain samādhi.

In Chinese Buddhism, the nianfo is specifically taken as a subject of meditation and is often practiced while counting with Buddhist prayer beads.[6]

In China, Pure Land and Chan Buddhism merged entirely by the Yuan dynasty. The modern Chan revitaliser Nan Huai-Chin taught that the nianfo is to be chanted slowly and the mind emptied out after each repetition. When idle thoughts arise, the nianfo is repeated again to clear them. With constant practice, the mind progressively empties and the meditator attains samādhi.[7]

In most Pure Land traditions, mindfully chanting of the name of Amitābha is viewed as allowing one to obtain birth in Amitābha's pure land, Sukhāvatī. It is felt that this act would help to negate vast stores of negative karma that might hinder one's pursuit of buddhahood. Sukhāvatī is a place of refuge where one can become enlightened without being distracted by the sufferings of our existence.

Various Pure Land schools in Japan have different interpretations of the nianfo, often based on faith in Amitābha rather than on meditation. In Jōdo Shinshū, the nianfo is reinterpreted as an expression of gratitude to Amitābha. The idea behind this is that rebirth into Sukhāvatī is assured the moment one first has faith in Amitābha.

Origins of the Nianfo

Andrew Skilton looks to an intermingling of Mahāyāna teachings with Buddhist meditation schools in Kashmir for the rise of Mahāyāna practices related to buddhānusmṛti:

Great innovations undoubtedly arose from the intermingling of early Buddhism and the Mahāyāna in Kashmir. Under the guidance of Sarvāstivādin teachers in the region, a number of influential meditation schools evolved which took as their inspiration the Bodhisattva Maitreya. [...] The Kashmiri meditation schools were undoubtably highly influential in the arising of the buddhānusmṛti practices, concerned with the 'recollection of the Buddha(s)', which were later to become characteristic of Mahāyāna Buddhism and the Tantra.[8]

The earliest dated sutra describing the nianfo is the Pratyutpanna Samādhi Sūtra (first century BCE), which is thought to have originated in ancient kingdom of Gandhāra. This sutra does not enumerate any vows of Amitābha or the qualities of his pure land, Sukhāvatī, but rather briefly describes the repetition of the name of Amitābha as a means to enter his realm through meditation.

Bodhisattvas hear about the Buddha Amitabha and call him to mind again and again in this land. Because of this calling to mind, they see the Buddha Amitabha. Having seen him they ask him what dharmas it takes to be born in the realm of the Buddha Amitabha. Then the Buddha Amitabha says to these bodhisattvas: 'If you wish to come and be born in my realm, you must always call me to mind again and again, you must always keep this thought in mind without letting up, and thus you will succeed in coming to be born in my realm.[9]

Both the Infinite Life Sutra and the Amitābha Sūtra subsequently included instructions for practicing buddhānusmṛti in this manner. However, it has not been determined which sūtra was composed first, and to what degree the practice of buddhānusmṛti had already been popularized in India. Buddhānusmṛti directed at other buddhas and bodhisattvas is also advocated in sūtras from this period, for figures such as Akṣobhya and Avalokiteśvara. The practice of buddhānusmṛti for Amitābha became very popular in India. With translations of the aforementioned sūtras as well as instruction from Indian monks, the practice rapidly spread to East Asia.

Nembutsu-ban

The term nembutsu-ban is applied to the event in Kyoto, Japan in 1207 where Hōnen and his followers were banned from the city and forced into exile. This occurred when the leaders of older schools of Buddhism persuaded the civil authorities to prohibit the newer practices including the recitation of Namu Amida Butsu.[10] The ban was lifted in 1211.

Nianfo in modern history

Thích Quảng Đức, a South Vietnamese Mahāyāna monk who famously burned himself to death in an act of protest against the anti-Buddhist policies of the Catholic President Ngo Dinh Diem, said the nianfo as his last words immediately before death. He sat in the lotus position, rotated a string of wooden prayer beads, and recited the words "Nam Mô A Di Đà Phật" before striking the match and dropping it on himself, continuing to recite Amitabha's name as he burnt.

References

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 580

- Buddhist Temples, Tri-State (1978). Shinshu Seiten Jodo Shin Buddhist Teachings (First ed.). 1710 Octavia Street, San Francisco, California 94109: Buddhist Churches of America. pp. 45, 46.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "阿彌陀佛".

- 淨業持名四十八法

- Nakamura, Hajime. Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes. 1999. p. 205

- Wei-an Cheng (2000). Taming the monkey mind: a guide to pure land practice, translation with commentary by Elder Master Suddhisukha; New York: Sutra Translation Committee of the U.S. and Canada, pp. 18–19

- Yuan, Margaret. Grass Mountain: A Seven Day Intensive in Ch'an Training with Master Nan Huai-Chin. York Beach: Samuel Weiser, 1986

- Skilton, Andrew. A Concise History of Buddhism. 2004. p. 162

- Paul Harrison, John McRae, trans. (1998). The Pratyutpanna Samādhi Sutra and the Śūraṅgama Samādhi Sutra, Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1-886439-06-0; pp. 2–3, 19

- Esben Andreasen (1998). Popular Buddhism in Japan: Shin Buddhist religion & culture. Honolulu, Hawai'i: University of Hawai'i Press.

Bibliography

- Baskind, James (2008). The Nianfo in Obaku Zen: A Look at the Teachings of the Three Founding Masters, Japanese Religions 33 (1-2),19-34

- Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157863.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grumbach, Lisa (2005). "Nenbutsu and Meditation: Problems with the Categories of Contemplation, Devotion, Meditation, and Faith", Pacific World, Third Series, 7, 91-105.

- Inagaki Hisao, trans., Stewart, Harold (2003). The Three Pure Land Sutras, 2nd ed., Berkeley, Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1-886439-18-4

- Jones, Charles B. (2001). Toward a Typology of Nien-fo: A Study in Methods of Buddha-Invocation in Chinese Pure Land Buddhism, Pacific World, Third Series, 3, 219–239.

- Keenan, John P. (1989). Nien-Fo (Buddha-Anusmrti): The Shifting Structure of Remembrance, Pacific World, New Series 5, 40-52

- Li-Ying, Kuo (1995), La récitation des noms de "buddha" en Chine et au Japon. T'oung Pao, Second Series 81 (4/5), 230-268

- Payne, Richard K. (2005). "Seeing Buddhas, Hearing Buddhas: Cognitive Significance of Nenbutsu as Visualization and as Recitation", Pacific World, Third Series, 7, 110-141

.jpg.webp)