Norodom Sihanouk

Norodom Sihanouk (Khmer: នរោត្តម សីហនុ; 31 October 1922 – 15 October 2012) was a Cambodian politician who led Cambodia in various capacities throughout his political career, but most often as the King of Cambodia. In Cambodia, he is known as Samdech Euv (Khmer: សម្តេចឪ, father prince). During his lifetime, Cambodia was variously called the French Protectorate of Cambodia (until 1953), the Kingdom of Cambodia (1953–70), the Khmer Republic (1970–75), Democratic Kampuchea (1975–79), the People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979–93), and again the Kingdom of Cambodia (from 1993).

| Norodom Sihanouk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

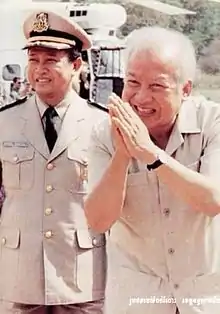

.jpg.webp) Norodom Sihanouk in 1983 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| King of Cambodia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First reign | 24 April 1941 – 2 March 1955 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronation | 3 May 1941 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Sisowath Monivong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Norodom Suramarit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Ministers | See list

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Second reign | 24 September 1993 – 7 October 2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronation | 24 September 1993 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Chea Sim (Regent) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Norodom Sihamoni | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Ministers | See list

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 31 October 1922 Phnom Penh, Cambodia, French Indochina (now Cambodia) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 15 October 2012 (aged 89) Beijing, China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | 13 July 2014 (interment of ashes) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

See list

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Issue | 14

See list

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House | House of Norodom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Norodom Suramarit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Sisowath Kossamak | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Prime Minister of Cambodia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of Sangkum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 March 1955 – 18 March 1970 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | None (party dissolved) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief of State of Cambodia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 20 June 1960 – 18 March 1970 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Sisowath Kossamak | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Chuop Hell (acting) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Cheng Heng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 June 1993 – 24 September 1993 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Himself as King | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the State Presidium of Democratic Kampuchea | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 17 April 1975 – 2 April 1976 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Khieu Samphan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Cavalry School | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sihanouk became king of Cambodia during French colonial rule in 1941 upon the death of his maternal grandfather, King Monivong. After the Japanese occupation of Cambodia during the Second World War, he secured Cambodian independence from France in 1953. He abdicated in 1955 and was succeeded by his father, Suramarit, so as to directly participate in politics. Sihanouk's political organization Sangkum won the general elections that year and he became prime minister of Cambodia. He governed it under one-party rule, suppressed political dissent, and declared himself Head of State in 1960. Officially neutral in foreign relations, in practice he was closer to the communist bloc. The Cambodian coup of 1970 ousted him and he fled to China and North Korea, there forming a government-in-exile and resistance movement. He encouraged Cambodians to fight the new government and backed the Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian Civil War. He returned as figurehead head of state after the Khmer Rouge's victory in 1975. His relations with the new government declined and in 1976 he resigned. He was placed under house arrest until Vietnamese forces overthrew the Khmer Rouge in 1979.

Sihanouk went into exile again and in 1981 formed FUNCINPEC, a resistance party. The following year, he became president of the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK), a broad coalition of anti-Vietnamese resistance factions which retained Cambodia's seat at the United Nations, making him Cambodia's internationally recognized head of state. In the late 1980s, informal talks were carried out to end hostilities between the Vietnam-supported People's Republic of Kampuchea and the CGDK. In 1990, the Supreme National Council of Cambodia was formed as a transitional body to oversee Cambodia's sovereign matters, with Sihanouk as its president. The 1991 Paris Peace Accords were signed and the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) was established the following year. The UNTAC organized the 1993 Cambodian general elections, and a coalition government, jointly led by his son Norodom Ranariddh and Hun Sen, was subsequently formed. He was reinstated as Cambodia's king. He abdicated again in 2004 and the Royal Council of the Throne chose his son, Sihamoni, as his successor. Sihanouk died in Beijing in 2012.

Between 1941 and 2006, Sihanouk produced and directed 50 films, some of which he acted in. The films, later described as being of low quality, often featured nationalistic elements, as did a number of the songs he wrote. Some of his songs were about his wife Queen Monique, the nations neighboring Cambodia, and the communist leaders who supported him in his exile. In the 1980s Sihanouk held concerts for diplomats in New York City. He also participated in concerts at his palace during his second reign.

Early life and first reign

Norodom Sihanouk was the only child born of the union between Norodom Suramarit and Sisowath Kossamak.[1] His parents, who heeded the Royal Court Astrologer's advice that he risked dying at a young age if he was raised under parental care, placed him under the care of Kossamak's grandmother, Pat. When Pat died, Kossamak brought Sihanouk to live with his paternal grandfather, Norodom Sutharot. Sutharot delegated parenting responsibilities to his daughter, Norodom Ket Kanyamom.[2] Sihanouk received his primary education at the François Baudoin school and Nuon Moniram school in Phnom Penh.[3] During this time, he received financial support from his maternal grandfather, Sisowath Monivong, to head an amateur performance troupe and soccer team.[1] In 1936, Sihanouk was sent to Saigon, where he pursued his secondary education at Lycée Chasseloup Laubat, a boarding school.[4]

When the reigning king Monivong died on 23 April 1941 the Governor-General of French Indochina, Jean Decoux, chose Sihanouk to succeed him.[5] Sihanouk's appointment as king was formalised the following day by the Cambodian Crown Council,[6] and his coronation ceremony took place on 3 May 1941.[7] During the Japanese occupation of Cambodia, he dedicated most of his time to sports, filming, and the occasional tour to the countryside.[8] In March 1945 the Japanese military, which had occupied Cambodia since August 1941, dissolved the nominal French colonial administration. Under pressure from the Japanese, Sihanouk proclaimed Cambodia's independence[9] and assumed the position of prime minister while serving as king at the same time.[10]

Pre-independence and self-rule

As prime minister, Sihanouk revoked a decree issued by the last resident superior of Cambodia, Georges Gautier, to romanise the Khmer alphabet.[11] Following the Surrender of Japan in August 1945, nationalist forces loyal to Son Ngoc Thanh launched a coup, which led to Thanh becoming prime minister.[12] When the French returned to Cambodia in October 1945, Thanh was dismissed and replaced by Sihanouk's uncle Sisowath Monireth.[13] Monireth negotiated for greater autonomy in managing Cambodia's internal affairs. A modus vivendi signed in January 1946 granted Cambodia autonomy within the French Union.[14] A joint French-Cambodian commission was set up after that to draft Cambodia's constitution,[15] and in April 1946 Sihanouk introduced clauses which provided for an elected parliament on the basis of universal male suffrage as well as press freedom.[16] The first constitution was signed into effect by Sihanouk in May 1947.[17] Around this time, Sihanouk made two trips to Saumur, France, where he attended military training at the Armoured Cavalry Branch Training School in 1946, and again in 1948. He was made a reserve captain in the French army.[18]

In early 1949, Sihanouk traveled to Paris with his parents to negotiate with the French government for more autonomy for Cambodia. The modus vivendi was replaced by a new Franco-Khmer treaty, which recognised Cambodia as "independent" within the French Union.[19] In practice, the treaty granted only limited self-rule to Cambodia. While Cambodia was given free rein in managing its foreign ministry and, to a lesser extent, its defence, most of the other ministries remained under French control.[20] Meanwhile, dissenting legislators from the national assembly attacked the government led by prime minister Penn Nouth over its failure to resolve deepening financial and corruption problems plaguing the country. The dissenting legislators, led by Yem Sambaur, who had defected from the Democrat party in November 1948,[21] deposed Penn Nouth.[22] Yem Sambaur replaced him, but his appointment did not sit well with the Democrats, who in turn pressured Sihanouk to dissolve the national assembly and hold elections.[23]

Sihanouk, who by now had tired of the political squabbling, dissolved the assembly in September 1949,[24] but opted to rule by decree for the next two years before general elections were held, which the Democrats won.[25] In October 1951, Thanh returned to Cambodia and was received by 100,000 supporters, a spectacle which Sihanouk saw as an affront to his regal authority.[26] Thanh disappeared six months later, presumably to join the Khmer Issarak.[27] Sihanouk ordered the Democrat-led government to arrest Thanh but was ignored.[28] Subsequently, civil demonstrations against the monarchy and the French broke out in the countryside,[29] alarming Sihanouk, who began to suspect that the Democrats were complicit.[30] In June 1952 Sihanouk dismissed the Democrat nominee Huy Kanthoul and made himself prime minister. A few days later, Sihanouk privately confided in exasperation to the US chargé d'affaires, Thomas Gardiner Corcoran, that parliamentary democracy was unsuitable for Cambodia.[30]

In January 1953, Sihanouk re-appointed Penn Nouth as prime minister before leaving for France. Once there, Sihanouk wrote to French President Vincent Auriol requesting that he grant Cambodia full independence, citing widespread anti-French sentiment among the Cambodian populace.[31] Auriol deferred Sihanouk's request to the French Commissioner for Overseas Territories, Jean Letourneau, who promptly rejected it. Subsequently, Sihanouk traveled to Canada and the United States, where he gave radio interviews to present his case. He took advantage of the prevailing anti-communist sentiment in those countries, arguing that Cambodia faced a Communist threat similar to that of the Viet Minh in Vietnam, and that the solution was to grant full independence to Cambodia.[32] Sihanouk returned to Cambodia in June 1953, taking up residence in Siem Reap.[33] He organised public rallies calling for Cambodians to fight for independence, and formed a citizenry militia which attracted about 130,000 recruits.[34]

In August 1953, France agreed to cede control over judicial and interior affairs to Cambodia, and in October 1953 the defense ministry as well. At the end of October, Sihanouk went to Phnom Penh,[35] where he declared Cambodia's independence from France on 9 November 1953.[33] In May 1954, Sihanouk sent two of his cabinet ministers, Nhiek Tioulong and Tep Phan, to represent Cambodia at the Geneva Conference.[36] The agreements affirmed Cambodia's independence and allowed it to seek military aid from any country without restrictions. At the same time, Sihanouk's relations with the governing Democrat party remained strained, as they were wary of his growing political influence.[37] To counter Democrat opposition, Sihanouk held a national referendum to gauge public approval for his efforts to seek national independence.[38] While the results showed 99.8 percent approval, Australian historian Milton Osborne noted that open balloting was carried out and voters were cowed into casting an approval vote under police surveillance.[39]

Sangkum era

Abdication and entry into politics

On 2 March 1955, Sihanouk suddenly abdicated the throne[33][40] and was in turn succeeded by his father, Suramarit.[3] His abdication surprised everyone, including his own parents.[41] In his abdication speech, Sihanouk explained that he was abdicating in order to extricate himself from the "intrigues" of palace life and allow easier access to common folk as an "ordinary citizen". According to Osborne, Sihanouk's abdication earned him the freedom to pursue politics while continuing to enjoy the deference that he had received from his subjects when he was king.[42] In addition, he also feared being cast aside by the government after discovering that his popularity was manufactured by his own officials.[43][41]

In April 1955, before leaving for a summit with Asian and African states in Bandung Indonesia, Sihanouk announced the formation his own political party, the Sangkum, and expressed interest in competing in the general elections slated to be held in September 1955. While the Sangkum was, in effect, a political party, Sihanouk argued that the Sangkum should be seen as a political "organisation", and explained that he could accommodate people with differing political orientations on the sole condition that they pledged fealty to the monarchy.[44] The creation of the Sangkum was seen as a move to dissolve the political parties.[45][46]

Sangkum was based on four small, monarchist, rightist parties, including the 'Victorious North-East' party of Dap Chhuon, the Khmer Renovation party of Lon Nol,[47] the People's Party[48] and the Liberal Party.[49] At the same time, Sihanouk was running out of patience with the increasingly leftist Democratic Party and the left-wing Pracheachon, as both had refused to merge into his party and had campaigned against him. He appointed as director of national security Dap Chhuon,[50] who ordered the national police to jail their leaders and break up their election rallies.[51] When elections were held, the Sangkum received 83 percent of all valid votes. They took up all seats in the National Assembly, replacing the Democrats, which had until then been the majority party.[52] The following month, Sihanouk was appointed as prime minister.[53]

Premiership (1955–60)

Once in office, Sihanouk introduced several constitutional changes, including extending suffrage to women, adopting Khmer as the sole official language of the country[54] and making Cambodia a constitutional monarchy by vesting policy-making powers in the prime minister rather than the king.[55] He viewed socialism as an ideal concept for establishing social equality and fostering national cohesion within newly independent Cambodia. In March 1956, he embarked on a national programme of "Buddhist socialism", promoting socialist principles on the one hand while maintaining the kingdom's Buddhist culture on the other.[56] Between 1955 and 1960, Sihanouk resigned and retook the post of prime minister several times, citing fatigue caused by overwork.[57] The National Assembly nominated experienced politicians such as Sim Var and San Yun to become prime minister whenever Sihanouk took leave, but they similarly relinquished their posts each time, several months into their term,[58] as cabinet ministers repeatedly disagreed over public policy matters.[59]

In May 1955, Sihanouk had accepted military aid from the US.[60] The following January, when he was in the Philippines on a state visit, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operatives attempted to sway him into placing Cambodia under Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) protection.[61] Subsequently, Sihanouk began to suspect that the US was attempting to undermine his government and that it was lending covert support to the Democratic party, now without parliamentary representation, for that purpose.[62] On the other hand, Sihanouk developed a good impression of China, whose premier, Zhou Enlai, gave him a warm reception on his first visit there in February 1956. They signed a friendship treaty in which China promised US$40 million in economic aid to Cambodia.[63] When Sihanouk returned from China, Sarit Thanarat and Ngo Dinh Diem, leaders of Thailand and South Vietnam, respectively, both with pro-American sympathies, started to accuse him of pro-Communist sympathies. South Vietnam briefly imposed a trade embargo on Cambodia, preventing trading ships from travelling up the Mekong river to Phnom Penh.[64] While Sihanouk professed that he was pursuing a policy of neutrality, Sarit and Diem remained distrustful of him, more so after he established formal diplomatic relations with China in 1958.[65]

The Democratic party continued to criticize the Sangkum and Sihanouk in their newspaper, much to Sihanouk's consternation.[66] In August 1957 Sihanouk finally lost patience, calling out Democrat leaders for a debate. Five of them attended. At the debate, held at the royal palace, Sihanouk spoke in a belligerent tone, challenging the Democrat leaders to present evidence of malfeasance in his government and inviting them to join the Sangkum. The Democrat leaders gave hesitant responses, and, according to American historian David P. Chandler, this gave the audience the impression that they were disloyal to the monarchy.[62] The debate led to the effective demise of the Democratic party, as its leaders were subsequently beaten up by government soldiers, with Sihanouk's tacit approval.[67] With the Democrats vanquished, Sihanouk focused on preparing for general elections, slated to be held in March 1958. He drafted left-wing politicians, including Hou Yuon, Hu Nim and Chau Seng, to stand as Sangkum candidates, with a view to winning left-wing support from the Pracheachon.[68] The Pracheachon on their part fielded five candidates for the elections. However, four of them withdrew, as they were prevented by the national police from holding any election rallies. When voting took place, the Sangkum won all seats in the national assembly.[69]

In December 1958 Ngo Dinh Nhu, Diem's younger brother and chief adviser, broached the idea of orchestrating a coup to overthrow Sihanouk.[70] Nhu contacted Dap Chhuon, Sihanouk's Interior Minister, who was known for his pro-American sympathies, to prepare for the coup against his boss.[71] Chhuon received covert financial and military assistance from Thailand, South Vietnam, and the CIA.[72] In January 1959 Sihanouk learned of the coup plans through intermediaries who were in contact with Chhuon.[73] The following month, Sihanouk sent the army to capture Chhuon, who was summarily executed as soon as he was captured, effectively ending the coup attempt.[74] Sihanouk then accused South Vietnam and the United States of orchestrating the coup attempt.[75] Six months later, on 31 August 1959, a small packaged lacquer gift fitted with a parcel bomb was delivered to the royal palace. Norodom Vakrivan, the chief of protocol, was killed instantly when he opened the package. Sihanouk's parents, Suramarit and Kossamak, were sitting in another room not far from Vakrivan. An investigation traced the origin of the parcel bomb to an American military base in Saigon.[76] While Sihanouk publicly accused Ngo Dinh Nhu of masterminding the bomb attack, he secretly suspected that the US was also involved.[77] The incident deepened his distrust of the US.[78]

Initial years as Head of State (1960–65)

Suramarit, Sihanouk's father, died on 3 April 1960[79] after several months of poor health that Sihanouk blamed upon the shock that his father had received from the parcel bomb attack.[76] The following day, the Cambodian Crown Council met to choose Monireth as regent.[80] Over the next two months, Sihanouk introduced constitutional amendments to create the new post of Head of State of Cambodia, which provided ceremonial powers equivalent to that of the king. A referendum held on 5 June 1960 approved Sihanouk's proposals, and Sihanouk was formally appointed Head of State on 14 June 1960.[81] As the head of state, Sihanouk took over various ceremonial responsibilities of the king, such as holding public audiences[82] and leading the Royal Ploughing Ceremony. At the same time, he continued to play an active role in politics as Sangkum's leader.[83]

In 1961 Pracheachon's spokesperson, Non Suon, criticized Sihanouk for failing to tackle inflation, unemployment, and corruption in the country. Non Suon's criticisms gave Sihanouk the impetus to arrest Pracheachon leaders, and, according to him, he had discovered plans by their party to monitor local political developments on behalf of foreign powers.[84] In May 1962 Tou Samouth, Pracheachon's secretary-general, disappeared, and its ideological ally, the Communist Party of Kampuchea, suspected that Samouth had been secretly captured and killed by police.[85] Sihanouk nevertheless allowed Sangkum's left-wing politicians to run again in the 1962 general elections, which they all won.[86] He even appointed two left-wing politicians, Hou Yuon and Khieu Samphan, as secretaries for planning and commerce, respectively, after the election.[87]

In November 1962, Sihanouk called on the US to stop supporting the Khmer Serei, which he believed they had been secretly doing through the CIA. He threatened to reject all economic aid from the US if they failed to respond to his demands,[88] a threat he later carried out on 19 November 1963.[89] At the same time, Sihanouk also nationalised the country's entrepot trade, banking sector, and distillery industries.[90] To oversee policy and regulatory matters on the country's entrepot trade, he set up the National Export-Import Corporation and Statutory Board, better known as "SONEXIM".[91] When Sarit, Diem, and US president John F. Kennedy died in November and December 1963, Sihanouk rejoiced over their deaths, as he accused them of attempting to destabilise Cambodia. He organised concerts and granted civil servants extra leave time to celebrate the occasion. When the US government protested Sihanouk's celebrations, he responded by recalling the Cambodian ambassador to the US, Nong Kimny.[92]

In early 1964, Sihanouk signed a secret agreement with North Vietnam and the Viet Cong, allowing Chinese military aid meant for them to be delivered through Sihanoukville's port. In turn, the Cambodian army would be paid for delivering food supplies to the Viet Cong, and at the same time skim off 10 percent of all military hardware supplies.[93] In addition, he also allowed the Viet Cong to build a trail through eastern Cambodia, so that their troops could receive war supplies from North Vietnam. The trail later became known as the Sihanouk Trail.[94] When the US learned of Viet Cong presence in eastern Cambodia, they started a bombing campaign,[95] spurring Sihanouk to sever diplomatic ties with the US in May 1965.[94] As a result of this secret agreement, Communist countries, including China, the Soviet Union, and Czechoslovakia, provided military aid to Cambodia.[96]

Continued leadership as Head of State (1966–70)

In September 1966, general elections were held,[97] and Sangkum legislators with conservative and right-wing sympathies dominated the national assembly. In turn, they nominated Lon Nol, a military general who shared their political sympathies, as prime minister. However, their choice did not sit well with Sihanouk.[98] To counterbalance conservative and right-wing influence, in October 1966 Sihanouk set up a shadow government made up of Sangkum legislators with left-wing sympathies.[99] At the end of the month, Lon Nol offered to resign from his position, but was ironically stopped from doing so by Sihanouk.[100] In April 1967, the Samlaut Uprising occurred, with local peasants fighting against government troops in Samlaut, Battambang.[101] As soon as government troops managed to quell the fighting,[102] Sihanouk began to suspect that three left-wing Sangkum legislators – Khieu Samphan, Hou Yuon and Hu Nim – had incited the rebellion.[103] When Sihanouk threatened to charge Khieu Samphan and Hou Yuon before a military tribunal, they fled into the jungle to join the Khmer Rouge, leaving Hu Nim behind.[104]

Lon Nol resigned as prime minister in early May 1967, and Sihanouk appointed Son Sann in his place.[103] At the same time, Sihanouk replaced conservative-leaning ministers appointed by Lon Nol with technocrats and left-leaning politicians.[104] In the later part of the month, after receiving news that the Chinese embassy in Cambodia had published and distributed Communist propaganda to the Cambodian populace praising the Cultural Revolution,[105] Sihanouk accused China of supporting local Chinese Cambodians in engaging in "contraband" and "subversive" activities.[106] In August 1967, Sihanouk sent to China his Foreign Minister, Norodom Phurissara, who unsuccessfully urged Zhou to stop the Chinese embassy from disseminating Communist propaganda.[107] In response, Sihanouk closed the Cambodia–Chinese Friendship Association in September 1967. When the Chinese government protested,[108] Sihanouk threatened to close the Chinese embassy in Cambodia.[109] Zhou stepped in to placate Sihanouk,[110] and compromised by instructing its embassy to send its publications to Cambodia's information ministry for vetting prior to distribution.[109]

As relations with China worsened, Sihanouk pursued rapprochement with the US. He learned that Kennedy's widow, Jacqueline Kennedy, had expressed a desire to see Angkor Wat.[111] Seeing this as an opportunity to restore relations with the US, Sihanouk invited her to visit Cambodia and personally hosted her visit in October 1967.[112] Jacqueline Kennedy's visit paved the way for Sihanouk to meet with Chester Bowles, the US ambassador to India. To Bowles, Sihanouk expressed his willingness to restore bilateral relations with the US, hinted at the presence of Viet Cong troops in Cambodia, and suggested he would turn a blind eye should US forces enter Cambodia to attack Viet Cong troops retreating into Cambodia from South Vietnam—a practice known as "hot pursuit"—provided that Cambodians were unharmed.[113][114] Silhanouk told Bowles that he disliked the Vietnamese as a people, saying he had no love for any Vietnamese, red, blue, North or South".[115] Kenton Clymer notes that this statement "cannot reasonably be construed to mean that Sihanouk approved of the intensive, ongoing B-52 bombing raids" the US launched in eastern Cambodia beginning in March 1969 as part of Operation Menu, adding: "In any event, no one asked him. ... Sihanouk was never asked to approve the B-52 bombings, and he never gave his approval."[114] The bombing forced the Viet Cong to flee from their jungle sanctuaries and seek refuge in populated towns and villages.[116] As a result, Sihanouk became concerned that Cambodia might get drawn into fighting in the Vietnam War. In June 1969, he extended diplomatic recognition to the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRGSV),[117] hoping that he could get the Viet Cong troops under its charge to leave Cambodia should they win the war. At the same time, he also openly admitted the presence of Viet Cong troops in Cambodia for the first time,[118] prompting the US to restore formal diplomatic relations with Cambodia three months later.[119]

As the Cambodian economy was stagnating due to systemic corruption,[120] Sihanouk opened two casinos – in Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville – in January 1969.[121] While the casinos satisfied his aim of generating state revenues of up to 700 million riels in that year, it also caused a sharp increase in the number of bankruptcies and suicides.[121] In August 1969 Lon Nol was reappointed as Prime Minister, with Sisowath Sirik Matak as his deputy. Two months later, Lon Nol left Cambodia to seek medical treatment, leaving Sirik Matak to run the government. Between October and December 1969, Sirik Matak instituted several policy changes that ran contrary to Sihanouk's wishes, such as allowing private banks to re-open in the country and devaluing the riel. He also encouraged ambassadors to write to Lon Nol directly, instead of going through Sihanouk, angering the latter.[122] In early January 1970, Sihanouk left Cambodia for medical treatment in France.[123] Shortly after he left, Sirik Matak took the opportunity to close down the casinos.[124]

Deposition, GRUNK and Khmer Rouge years

In January 1970, Sihanouk left Cambodia for a two-month holiday in France, spending his time at a luxury resort in the French Riviera.[125] On 11 March 1970, a large protest took place outside the North Vietnamese and PRGSV embassies, as protesters demanded Viet Cong troops withdraw from Cambodia. The protests turned chaotic, as protesters looted both embassies and set them on fire, alarming Sihanouk.[126] Sihanouk, who was in Paris at the time, considered both returning to quell the protests and visiting Moscow, Beijing, and Hanoi. He opted for the latter, thinking that he could persuade its leaders to recall Viet Cong troops to their jungle sanctuaries, where they had originally established themselves between 1964 and 1969.[127] Five days later, Oum Mannorine, the half-brother of Sihanouk's wife Monique, was summoned to the National Assembly to answer corruption charges.[128] On that night after the hearing, Mannorine ordered troops under his command to arrest Lon Nol and Sirik Matak, but ended up getting arrested by Lon Nol's troops instead. On 18 March 1970 the National Assembly voted to depose Sihanouk,[129] allowing Lon Nol to assume emergency powers.[130]

On that day, Sihanouk was in Moscow meeting Soviet foreign minister Alexei Kosygin, who broke the news as he was being driven to the Moscow airport.[131][132] From Moscow, Sihanouk flew to Beijing, where he was received by Zhou. Zhou arranged for the North Vietnamese Prime Minister, Pham Van Dong to fly to Beijing from Hanoi and meet with Sihanouk.[133] Zhou greeted Sihanouk very warmly, telling him that China still recognized as the legitimate leader of Cambodia and would pressing North Korea together with several Middle Eastern and African nations not to recognize Lon Nol's government, saying that once China issued its declaration of support "the Soviet Union will be embarrassed and will have to reconsider".[134] Both Zhou and Dong encouraged Sihanouk to rebel against Lon Nol and promised him military and financial support. On 23 March 1970, Sihanouk announced the formation of his resistance movement, the National United Front of Kampuchea (FUNK). He encouraged the Cambodian populace to join him and fight against Lon Nol's government. Sihanouk was revered by the Khmer peasantry as a god-like figure, and his endorsement of the Khmer Rouge had immediate effects.[135] The royal family was so revered that Lon Nol after the coup went to the royal palace, knelt at the feet of the queen mother and begged her forgiveness for deposing her son.[136] Khmer Rouge soldiers broadcast Sihanouk's message in the Cambodian countryside, which roused demonstrations rooting for his cause that were brutally suppressed by Lon Nol's troops.[137] Sometime later, on 5 May 1970, Sihanouk announced the formation of a government-in-exile known as the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea (GRUNK), leading Communist countries including China, North Vietnam, and North Korea to break relations with the Lon Nol regime.[138] In Phnom Penh, a military trial convened on 2 July 1970, whereby Sihanouk was charged with treason and corruption in his capacity as Head of State. After a three-day trial, the judges ruled Sihanouk guilty of both charges and sentenced to him death in absentia on 5 July 1970.[139]

Between 1970 and 1975, Sihanouk took up residence in state guesthouses at Beijing and Pyongyang, courtesy of the Chinese and North Korean governments, respectively.[140] In February 1973, Sihanouk traveled to Hanoi, where he started on a long journey with Khieu Samphan and other Khmer Rouge leaders. The convoy proceeded along the Ho Chi Minh trail and reached the Cambodian border at Stung Treng Province the following month. From there, they traveled across the provinces of Stung Treng, Preah Vihear, and Siem Reap. Throughout this entire leg of the journey, Sihanouk faced constant bombardment from American planes participating in Operation Freedom Deal.[141] At Siem Reap, Sihanouk visited the temples of Angkor Wat, Banteay Srei, and Bayon.[142] In August 1973, Sirik Matak wrote an open letter calling on Sihanouk to bring the Cambodian Civil War to an end and suggesting the possibility of his return to the country. When the letter reached Sihanouk, he angrily rejected Sirik Matak's entreaties.[143]

After the Khmer Republic fell to the Khmer Rouge on 17 April 1975, a new regime under its charge, Democratic Kampuchea, was formed. Sihanouk was appointed as its Head of State, a ceremonial position.[144] In September 1975,[145] Sihanouk briefly returned to Cambodia to inter the ashes of his mother,[146] before going abroad again to lobby for diplomatic recognition of Democratic Kampuchea.[147] He returned on 31 December 1975 and presided over a meeting to endorse the constitution of Democratic Kampuchea.[148] In February 1976, Khieu Samphan took him on a tour across the Cambodian countryside. Sihanouk was shocked to see the use of forced labour and population displacement carried out by the Khmer Rouge government, known as the Angkar. Following the tour, Sihanouk decided to resign as the Head of State.[149] The Angkar initially rejected his resignation request, though they subsequently accepted it in mid-April 1976, retroactively backdating it to 2 April 1976.[150]

From this point onwards Sihanouk was kept under house arrest at the royal palace. In September 1978, he was removed to another apartment in Phnom Penh's suburbs, where he lived until the end of the year.[151] Throughout his confinement, Sihanouk made several unsuccessful requests to the Angkar to travel overseas.[152] Vietnam invaded Cambodia on 22 December 1978. On 1 January 1979, Sihanouk was taken from Phnom Penh to Sisophon, where he stayed for three days until 5 January, when he was taken back to Phnom Penh.[153] Sihanouk was taken to meet Pol Pot, who briefed him on the Angkar's plans to repulse Vietnamese troops.[154] On 6 January 1979, Sihanouk was allowed to fly to Beijing from Phnom Penh, where he was greeted by Zhou Enlai's successor, Deng Xiaoping.[155] The next day Phnom Penh fell to advancing Vietnamese troops on 7 January 1979. On 9 January 1979, Sihanouk flew from Beijing to New York to attend the UN Security Council, where he simultaneously condemned the Khmer Rouge for orchestrating the Cambodian genocide as well as the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia.[156] Sihanouk subsequently sought asylum in China after making two unsuccessful asylum applications with the US and France.[157]

FUNCINPEC and CGDK years

After the Khmer Rouge regime was overthrown, a new Cambodian government supported by Vietnam, the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK), was established. The Chinese leader, Deng Xiaoping, was unhappy[158] with Vietnam's influence over the PRK government. Deng proposed to Sihanouk that he co-operate with the Khmer Rouge to overthrow the PRK government, but the latter rejected it,[159] as he opposed the genocidal policies pursued by the Khmer Rouge while they were in power.[158] In March 1981, Sihanouk established a resistance movement, FUNCINPEC which was complemented by a small resistance army known as Armée Nationale Sihanoukiste (ANS).[160] He appointed In Tam, who had briefly served as Prime Minister in the Khmer Republic, as the commander-in-chief of ANS.[161] The ANS needed military aid from China, and Deng seized the opportunity to sway Sihanouk into collaborating with the Khmer Rouge.[162] Sihanouk reluctantly agreed, and started talks in March 1981 with the Khmer Rouge and the Son Sann-led Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF) on a unified anti-PRK resistance movement.[163]

After several rounds of negotiations mediated by Deng and Singapore's prime minister Lee Kuan Yew,[164] FUNCINPEC, KPNLF, and the Khmer Rouge agreed to form the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) in June 1982. The CGDK was headed by Sihanouk, and functioned as a government-in-exile.[165] The UN defeated a resolution to expel Democratic Kampuchea and admit the PRK, effectively confirming Sihanouk as Cambodia's internationally recognized head of state.[166]

As CGDK chairperson, Sihanouk unsuccessfully negotiated, over the next five years, with the Chinese government to broker a political settlement to end the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia.[167] During this period, Sihanouk appointed two of his sons, Norodom Chakrapong and Norodom Ranariddh, to lead the ANS. Chakrapong was appointed as the deputy chief-of-staff for the ANS in March 1985,[168] while Ranariddh was minted to the twin positions of commander-in-chief and the chief-of-staff of the ANS in January 1986, replacing Tam.[169] In December 1987, the Prime Minister of the PRK government, Hun Sen, first met with Sihanouk to discuss ending the protracted Cambodian–Vietnamese War.[170] The following July, the then-foreign minister of Indonesia, Ali Alatas, brokered the first round of meetings between the four warring Cambodian factions consisting of FUNCINPEC, Khmer Rouge, KPNLF, and the PRK government over the future of Cambodia. Two more rounds of meetings were held in February and May 1989; since all were held near Jakarta, they became known as the Jakarta Informal Meetings (JIM).[171]

In July 1989, Ali Alatas joined French foreign minister Roland Dumas in opening the Paris Peace Conference, where discussions took place regarding plans for Vietnamese troop withdrawal and power-sharing arrangements in a hypothetical future Cambodian government.[171] The following month, Sihanouk resigned as president of FUNCINPEC[172] but remained in the party as an ordinary member.[173] In September 1990, the United Nations (UN) sponsored the establishment of the Supreme National Council of Cambodia (SNC), an administrative body responsible for overseeing the sovereign affairs of Cambodia for an interim period until UN-sponsored elections were held.[174] The creation of the SNC was subsequently ratified with United Nations Security Council Resolution 668.[175] In July 1991 Sihanouk left FUNCINPEC altogether and was elected as the chairperson of the SNC.[176]

UNTAC administration era

On 23 October 1991, Sihanouk led the FUNCINPEC, Khmer Rouge, KPNLF, and PRK into signing the Paris Peace Accords. The accords recognised the SNC as a "legitimate representative of Cambodian sovereignty" and created the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) to serve as a transitional government between 1992 and 1993.[177] In turn, UNTAC was given the mandate to station peacekeeping troops in Cambodia to supervise the disarmament of troops from the four warring Cambodian factions and to carry out national elections by 1993.[178] Sihanouk subsequently returned to Phnom Penh on 14 November 1991. Together with Hun Sen, Sihanouk rode in an open top limousine from Pochentong Airport all the way to the royal palace, greeting city residents who lined the streets to welcome his return.[179] The UNTAC administration was set up in February 1992, but stumbled in its peacekeeping operations as the Khmer Rouge refused to cooperate in disarmament.[180] In response, Sihanouk urged UNTAC to abandon the Khmer Rouge from the peacekeeping process on two occasions, in July and September 1992. During this period, Sihanouk mostly resided in Siem Reap and occasionally traveled by helicopter to supervise election preparations in KPNLF, FUNCINPEC, and Khmer Rouge resistance bases.[181]

Sihanouk left in November 1992 to seek medical treatment in Beijing,[182] where he stayed for the next six months until his return to Cambodia in May 1993, on the eve of elections.[183] While in Beijing, Sihanouk proposed a Presidential system government for Cambodia to then-UN secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali, but soon dropped the idea after facing opposition from the Khmer Rouge.[184] When general elections were held, FUNCINPEC, now headed by Sihanouk's son Norodom Ranariddh, won, while the Cambodian People's Party (CPP) headed by Hun Sen came in second.[185] The CPP was unhappy with the election results, and on 3 June 1993 Hun Sen and Chea Sim called on Sihanouk to lead the government. Sihanouk complied, and announced the formation of a Provisional National Government (PRG) headed by him, with Hun Sen and Ranariddh as his deputies.[186] Ranariddh was surprised at Sihanouk's announcement, as he had not been informed of his father's plans, and joined Australia, China, the United Kingdom, and the United States in opposing the plan. The following day, Sihanouk rescinded his announcement through a national radio broadcast.[187]

On 14 June 1993, Sihanouk was reinstated as the head of state in a constituent assembly session presided over by Ranariddh, who took the opportunity to declare the 1970 coup d'état which overthrew Sihanouk as "illegal".[188] As Head of State, Sihanouk renamed the Cambodian military to its pre-1970 namesake, the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces. He also issued orders to officially rename the country from the State of Cambodia to simply "Cambodia", reinstating "Nokor Reach" as the National Anthem of Cambodia with some minor modifications to its lyrics, and the Cambodian flag to its pre-1970 design.[189] At the same time, Sihanouk appointed Ranariddh and Hun Sen co-prime ministers, with equal powers.[190] This arrangement, which was provisional, was ratified by the Constituent Assembly on 2 July 1993.[188] On 30 August 1993,[191] Ranariddh and Hun Sen met with Sihanouk and presented two draft constitutions, one of them stipulating a constitutional monarchy headed by a king, and another a republic led by a head of state. Sihanouk opted for the draft stipulating Cambodia a constitutional monarchy,[192] which was ratified by the constituent assembly on 21 September 1993.[193]

Second reign

The new constitution came into force on 24 September 1993, and Sihanouk was reinstated as the King of Cambodia.[194] A permanent coalition government was formed between FUNCINPEC, CPP and a third political party, the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party (BLDP). In turn, Sihanouk made Ranariddh and Hun Sen First and Second Prime Ministers, respectively.[195] Shortly after that, Sihanouk left for Beijing, where he spent several months for cancer treatment.[196] In April 1994, Sihanouk returned[197] and the following month called the government to hold new elections so that the Khmer Rouge could be co-opted into the government. Both Ranariddh and Hun Sen rejected his suggestion,[198][199] but Sihanouk pressed on, and further proposed a national unity government consisting of FUNCINPEC, CPP, and the Khmer Rouge headed by him.[200] Again, both prime ministers rejected Sihanouk's proposal, arguing that Khmer Rouge's past intransigent attitude made the proposal unrealistic.[201][202] Sihanouk backed down, and expressed frustration that Hun Sen and Ranariddh had been ignoring him. As both Norodom Sirivudh[203] and Julio Jeldres, his younger half-brother and official biographer, respectively, saw it, this was a clear sign that the monarchy's ability to exert control over national affairs had diminished, at least vis-a-vis the prime ministers.[204]

In July 1994, one of his sons, Norodom Chakrapong, led a failed coup attempt to topple the government.[205] Following the coup attempt, Chakrapong took refuge in a hotel in Phnom Penh, but government troops soon discovered his hideout and surrounded the hotel. Chakrapong called Sihanouk, who negotiated with government representatives to allow him to go into exile in Malaysia.[206] The following November, Sirivudh was accused of plotting to assassinate Hun Sen and imprisoned. Sihanouk intervened to have Sirivudh detained at the interior ministry's headquarters, convinced that there was a secret plan to kill the latter if he were to remain in prison.[207] After Sirivudh was relocated to the safer location, Sihanouk appealed to Hun Sen that Sirivudh be allowed to go into exile in France together with his family. Subsequently, Hun Sen accepted his offer.[208]

Relations between the two co-prime ministers, Ranariddh and Hun Sen, deteriorated from March 1996,[209] when the former accused the CPP of repeatedly delaying the allocation process of low-level government posts to FUNCINPECs.[210] Ranariddh threatened to pull out of the coalition government[211] and hold national elections in the same year if his demands were not met,[212] stoking unease among Hun Sen and other CPP officials.[212] The following month, Sihanouk presided over a meeting between several royal family members and senior FUNCINPEC officials in Paris. Sihanouk attempted to reduce tensions between FUNCINPEC and the CPP by assuring that FUNCINPEC would not leave the coalition government and that there were no reactionary elements planning to bring down Hun Sen or the CPP.[213] In March 1997, Sihanouk expressed his willingness to abdicate the throne, claiming that rising anti-royalist sentiment among the populace was threatening the monarchy's existence.[214] In response, Hun Sen tersely warned Sihanouk that he would introduce constitutional amendments to prohibit members of the royal family from participating in politics if he followed through on his suggestion.[215] As Widyono saw it, Sihanouk remained popular with the Cambodian electorate, and Hun Sen feared that, should he abdicate and enter politics, he would win in any future elections, thereby undercutting CPP's political clout.[214]

In July 1997, violent clashes erupted in Phnom Penh between infantry forces separately allied to the CPP and FUNCINPEC, which effectively led to Ranariddh's ousting after FUNCINPEC forces were defeated.[216] Sihanouk voiced displeasure with Hun Sen for orchestrating the clashes, but refrained from calling Ranariddh's ouster a "coup d'état", a term which FUNCINPEC members used.[217] When the National Assembly elected Ung Huot as the First Prime Minister to replace Ranariddh on 6 August 1997,[218] Sihanouk charged that Ranariddh's ouster was illegal and renewed his offer to abdicate the throne, a plan which did not materialize.[219] In September 1998, Sihanouk meditated political talks in Siem Reap after the FUNCINPEC and the Sam Rainsy Party (SRP) staged protests against the CPP-led government for irregularities over the 1998 general elections. The talks broke down at the end of the month after Hun Sen narrowly escaped an assassination attempt, which he accused Sam Rainsy of masterminding.[220] Two months later, in November 1998, Sihanouk brokered a second round of political talks between the CPP and FUNCINPEC[221] whereby an agreement was reached for another coalition government between the CPP and FUNCINPEC.[220]

Sihanouk maintained a monthly bulletin in which he wrote commentaries on political issues and posted old photos of Cambodia in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1997 a character known by the name of "Ruom Rith" first appeared in his monthly bulletin, expressing critical comments on Hun Sen and the government. Hun Sen became offended by Ruom Rith's criticisms, and on at least two occasions in 1998 and 2003 persuaded Sihanouk to stop publishing his comments.[222][223] According to Ranariddh, Ruom Rith was an alter ego of Sihanouk, a claim which the latter vehemently denied.[224] In July 2002, Sihanouk expressed concern over the absence of detailed constitutional provisions over the organization and functioning of the Cambodian throne council.[225] When Hun Sen rejected Sihanouk's concern, the latter followed up in September 2002 by threatening to abdicate, so as to force the throne council to convene and elect a new monarch.[226]

In July 2003, general elections were held again, and the CPP won. However, they failed to secure two-thirds of all parliamentary seats, as required by the constitution to form a new government. The two runner-up parties of the election, FUNCINPEC and SRP, blocked the CPP from doing so.[227] Instead, in August 2003 they filed complaints with the Constitutional Council over alleged electoral irregularities.[228] After their complaints were rejected, FUNCINPEC and SRP threatened to boycott the swearing-in ceremony of parliamentarians. Sihanouk coaxed both parties to change their decision, stating that he would abstain from presiding over the ceremony as well if they did not comply with his wishes.[229] Both parties eventually backed off from their threats, and the swearing-in ceremony was held in October 2003, with Sihanouk in attendance.[230] The CPP, FUNCINPEC, and SRP held additional talks into 2004 to break the political stalemate, but to no avail. At the same time, Sihanouk proposed a unity government jointly led by politicians from all three political parties, which Hun Sen and Ranariddh both rebuffed.[231][232]

Abdication and final years

On 6 July 2004, in an open letter, Sihanouk announced his plans to abdicate once again. At the same time, he criticised Hun Sen and Ranariddh for ignoring his suggestions on how to resolve the political stalemate of the past year. Meanwhile, Hun Sen and Ranariddh had agreed to introduce a constitutional amendment that provided for an open voting system, requiring parliamentarians to select cabinet ministers and the president of the National Assembly by a show of hands. Sihanouk disapproved of the open voting system, calling upon Senate President Chea Sim not to sign the amendment. When Chea Sim heeded Sihanouk's advice, he was ferried out of the country shortly before the National Assembly convened to vote on the amendment on 15 July.[233] On 17 July 2004, the CPP and FUNCINPEC agreed to form a coalition government, leaving SRP out as an opposition party.[234] On 6 October 2004, Sihanouk wrote a letter calling for the throne council to convene and select a successor. The National Assembly and Senate both held emergency meetings to pass laws allowing for the abdication of the monarch. On 14 October 2004, the throne council unanimously voted to select Norodom Sihamoni as Sihanouk's successor.[235] Sihamoni was crowned as the King of Cambodia on 29 October 2004.[236]

In March 2005, Sihanouk accused Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam of encroaching into Cambodian territory, through unilateral border demarcation exercises without Cambodian participation. Two months later, Sihanouk formed the Supreme National Council on Border Affairs (SNCBA), which he headed, to address these concerns.[236] While the SRP and Chea Sim expressed support for Sihanouk for the formation of the SNCBA, Hun Sen decided to form a separate body, National Authority on Border Affairs (NABA), to deal with border concerns, with SNCBA to serve only as an advisory body.[237] After Hun Sen signed a border treaty with Vietnam in October 2005, Sihanouk dissolved the SNCBA.[238] In August 2007, the Cambodian Action Committee for Justice and Equity, a US-based human rights NGO, called for Sihanouk's State immunity to be lifted, so as to allow him to testify in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC).[239] Sihanouk responded to the call by inviting the ECCC public affairs officer, Peter Foster, for a discussion session on his personal experience under the Khmer Rouge regime.[240] Both Hun Sen and FUNCINPEC criticized the suggestion, with the latter accusing the NGO of being disrespectful.[239] The ECCC subsequently rejected Sihanouk's invitation.[241]

The following year, bilateral relations between Thailand and Cambodia became strained due to overlapping claims on the land area surrounding Preah Vihear Temple. Sihanouk issued a communiqué in July 2008 emphasising the Khmer architecture of the temple as well as ICJ's 1962 ruling of the temple in favour of Cambodia.[242] In August 2009, Sihanouk stated that he would stop posting messages on his personal website as he was getting old, making it difficult for him to keep up with his personal duties.[243] Between 2009 and 2011, Sihanouk spent most of his time in Beijing for medical care. He made a final public appearance in Phnom Penh on his 89th birthday and 20th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords on 30 October 2011. Thereafter, Sihanouk expressed his intent to stay in Cambodia indefinitely,[244] but returned to Beijing in January 2012 for further medical treatment at the advice of his Chinese doctors.[245]

Death and funeral

In January 2012, Sihanouk issued a letter in which he expressed his wish that his body be cremated after his death, and his ashes be interred in a golden urn.[246] A few months later, in September 2012, Sihanouk said that he would not return to Cambodia from Beijing for his 90th birthday, citing fatigue.[247] On 15 October 2012, Sihanouk died of a heart attack at 1:20 am, Phnom Penh time.[248] When the news broke, Sihamoni, Hun Sen, and other government officials flew to Beijing to pay their last respects.[249] The Cambodian government announced an official mourning period of seven days between 17 and 24 October 2012, and state flags were ordered to fly at one-third height. Two days later, Sihanouk's body was brought back from Beijing on an Air China flight,[250] and about 1.2 million people lined the streets from the airport to the royal palace to witness the return of Sihanouk's cortège.[251]

In late November 2012, Hun Sen said that Sihanouk's funeral and cremation were to be carried out in February 2013. Sihanouk's body lay in state at the royal palace for[252] the next three months until the funeral was held on 1 February 2013.[253] A 6,000-metre (20,000 ft) street procession was held, and Sihanouk's body was subsequently kept at the royal crematorium until 4 February 2013 when his body was cremated.[254] The following day, the royal family scattered some of Sihanouk's ashes into the Tonle Sap river, while the rest were kept in the palace's throne hall for about a year.[255] In October 2013, a stupa featuring a bronze statue of Sihanouk was inaugurated next to the Independence Monument.[256] In July 2014, Sihanouk's ashes were interred at the silver pagoda next to those of one of his daughters, Kantha Bopha.[257]

Artistic works

Film-making

Sihanouk produced about 50 films throughout his lifetime.[258] He developed an interest in the cinema at a young age, which he attributed to frequent trips to the cinema with his parents.[1] Shortly after becoming king in 1941, Sihanouk made a few amateur films,[259] and sent Cambodian students to study film-making in France.[260] When the film Lord Jim was released in 1965, Sihanouk was vexed with the negative portrayal it gave of Cambodia.[261] In response, Sihanouk produced his first feature film, Apsara, in 1966. He went on to produce, direct, and act in eight more films between 1966 and 1969, roping in members of the royal family and military generals to star in his films.[262] Sihanouk expressed that his films were created with the intent of portraying Cambodia in a positive light;[263] Milton Osborne also noted that the films were filled with Cold War[264] and nationalist propaganda themes.[265] Sihanouk's former adviser, Charles Meyer, said that his films created from the 1960s were of amateur standard, while the director of Reyum Institute, Ly Daravuth, similarly commented in 2006 that his films lacked artistic qualities.[259]

In 1967, one of his films, The Enchanted Forest, was nominated at the 5th Moscow International Film Festival.[266] In 1968, Sihanouk launched the Phnom Penh International Film Festival, which was held for a second time in 1969. In both years, a special award category was designated, the Golden Apsara Prize, of which Sihanouk was its only nominee and winner.[265] After Sihanouk was ousted in 1970, he ceased producing films for the next seventeen years until 1987.[267] In 1997, Sihanouk received a special jury prize from the International Film Festival of Moscow, where he revealed that he had received a budget ranging from US$20,000 to US$70,000 for each of his film productions from the Cambodian government. Six years later, Sihanouk donated his film archives to the École française d'Extrême-Orient in France and Monash University in Australia.[259] In 2006, he produced his last film, Miss Asina,[260] and then declared his retirement from film-making in May 2010.[268]

Music

Sihanouk wrote at least 48 musical compositions between the late 1940s and the early 1970s,[269] combining both traditional Khmer and Western themes into his works.[270] From the 1940s until the 1960s, Sihanouk's compositions were mostly based on sentimental, romantic and patriotic themes. Sihanouk's romantic songs reflected his numerous romantic liaisons, particularly his relationship with his wife Monique,[271] and compositions such as "My Darling" and "Monica" were dedicated to her. He also wrote nationalistic songs, meant to showcase the beauty of provincial towns and at the same time foster a sense of patriotism and national unity among Cambodians. Notable compositions, such as "Flower of Battambang", "Beauty of Kep City", "Phnom Kulen", and "Phnom Penh", are examples of these. A few of his other compositions, including "Luang Prabang", "Nostalgia of China", and "Goodbye Bogor" were sentimental songs[272] about neighbouring countries including Laos, Indonesia, and China.[273]

After he was ousted as head of state in 1970, Sihanouk wrote several revolutionary-style songs[274] that praised the leaders of Communist countries, including "Hommage Khmer au Maréchal Kim Il Sung" and "Merci, Piste Ho Chi Minh". They were intended to show his gratitude toward the Communist leaders, which had supported GRUNK between 1970 and 1975.[275] From a young age,[1] Sihanouk learned to play several musical instruments including the clarinet, saxophone, piano, and accordion.[266] In the 1960s, Sihanouk led a musical band made up of his relatives, who would perform French songs and his own personal compositions for diplomats at the royal palace.[276] In his tours across Cambodian provinces, Sihanouk was accompanied by the Royal Military Orchestra and Cambodian pop singers.[273] Later, while Sihanouk was living in exile during the 1980s, he hosted concerts to entertain diplomats whenever he visited the United Nations Headquarters in New York City.[277] After he was reinstated as king in 1993, Sihanouk continued to perform in concerts held at the royal palace on an occasional basis.[278]

Titles and styles

| Styles of King Norodom Sihanouk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sir |

Sihanouk was known by many formal and informal titles throughout his lifetime,[279] and the Guinness Book of World Records identifies Sihanouk as the royal who had served the greatest variety of state and political offices.[280] When Sihanouk became king in 1941, he was bestowed with the official title of "Preah Bat Samdech Preah Norodom Sihanouk Varman" (ព្រះបាទសម្តេចព្រះ នរោត្តម សីហនុ វរ្ម័ន), which he used for both reigns between 1941 and 1955 and again from 1993 to 2004.[7] He reverted to the title of Prince after he abdicated 1955, and in that year was given by his father and successor the title of "Samdech Preah Upayuvareach" (សម្តេចព្រះឧបយុវរាជ),[33] which translates in English as "The Prince who has been King".[281] Starting from the early 1960s when he became the Head of State,[282] Sihanouk was affectionately known to most Cambodians as "Samdech Euv" (សម្តេចឪ),[283] which translates as the "Prince Father" in English.[280]

In 2004, after his second abdication, Sihanouk became known as the King Father of Cambodia,[284] with the official title of "Preah Karuna Preah Bat Sâmdach Preah Norodom Sihanouk Preahmâhaviraksat" (Khmer: ព្រះករុណាព្រះបាទសម្តេចព្រះ នរោត្តម សីហនុ ព្រះមហាវីរក្សត្រ).[280] He was also referred to by another honorific, "His Majesty King Norodom Sihanouk The Great Heroic King King-Father of Khmer independence, territorial integrity and national unity" (ព្រះករុណា ព្រះបាទសម្ដេចព្រះ នរោត្តម សីហនុ ព្រះមហាវីរក្សត្រ ព្រះវររាជបិតាឯករាជ្យ បូរណភាពទឹកដី និងឯកភាពជាតិខ្មែរ).[285] At the same time, he issued a royal decree requesting to be called "Samdech Ta" (សម្ដេចតា) or "Samdech Ta-tuot" (សម្ដេចតាទួត),[286] which translates as "Grandfather" and "Great-grandfather", respectively, in English.[287] When Sihanouk died in October 2012, he was bestowed by his son Sihamoni with the posthumous title of "Preah Karuna Preah Norodom Sihanouk Preah Borom Ratanakkot" (ព្រះករុណាព្រះនរោត្តម សីហនុ ព្រះបរមរតនកោដ្ឋ), which literally translates as "The King who lies in the Diamond Urn" in English.[288]

Personal life

Sihanouk's name is derived from two Sanskrit words "Siha" (सिंह) and "Hanu" (हनु), which translates as "Lion" and "Jaws", respectively, in English.[289][290] He was fluent in Khmer, French, and English,[291] and also learned Greek and Latin in high school.[292] In his high school days, Sihanouk played football, basketball, volleyball, and also took up horse riding.[1] He suffered from diabetes and depression in the 1960s,[293] which flared up again in the late 1970s while living in captivity under the Khmer Rouge.[294] In November 1992, Sihanouk suffered a stroke[295] caused by the thickening of the coronary arteries and blood vessels.[296] In 1993, he was diagnosed with B cell lymphoma in the prostate[297] and was treated with chemotherapy and surgery.[298] Sihanouk's lymphoma went into remission in 1995,[299] but returned again in 2005 in the gastric region. He suffered a third bout of lymphoma in 2008,[297] and after prolonged treatment it went into remission the following year.[300]

In 1960, Sihanouk built a personal residence at Chamkarmon District where he lived over the next ten years as the Head of State.[301] Following his overthrow in 1970, Sihanouk took up residence in Beijing, where he lived at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in the first year of his stay. In 1971, Sihanouk moved to a larger residence in the city that once housed the French embassy.[302] The residence was equipped with a temperature-adjustable swimming pool,[140] cinema[303] and seven chefs.[304] In 1974 North Korean leader Kim Il-sung built Changsuwon, a 40-room mansion, for Sihanouk.[305] Changsuwon was built near an artificial lake, and Sihanouk spent time taking boat trips there and also shot a few films within the compound.[306] In August 2008, Sihanouk declared his assets on his website, which according to him consisted of a small house in Siem Reap and 30,000 Euros of cash savings stored in a French bank. He also stated that his residences in Beijing and Pyongyang were guesthouses owned by the governments of China and North Korea, respectively, and that they did not belong to him.[307]

Family

In April 1952 Sihanouk married Paule Monique Izzi, who was the daughter of Pomme Peang, a Cambodian, and Jean-François Izzi, a French banker of Italian ancestry.[308] Monique became Sihanouk's lifelong partner;[123] in the 1990s she changed her name to Monineath.[309] Before his marriage to Monique, Sihanouk married five other women: Phat Kanhol, Sisowath Pongsanmoni, Sisowath Monikessan, Mam Manivan Phanivong, and Thavet Norleak.[310] Monikessan died in childbirth in 1946; his marriages to the other four women all ended in divorce.[311] Sihanouk had fourteen children with five different wives. Thavet Norleak bore him no children.[312] During the Khmer Rouge years, five children and fourteen grandchildren disappeared; Sihanouk believed they were killed by the Khmer Rouge.[313][314]

Sihanouk had the following issue:

| Name | Year of birth | Year of death | Mother | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norodom Buppha Devi | 1943 | 2019 | Phat Kanhol | |

| Norodom Yuvaneath | 1943 | Sisowath Pongsanmoni | ||

| Norodom Ranariddh | 1944 | Phat Kanhol | ||

| Norodom Ravivong | 1944 | 1973 | Sisowath Pongsanmoni | Malaria[315] |

| Norodom Chakrapong | 1945 | Sisowath Pongsanmoni | ||

| Norodom Naradipo | 1946 | 1976 | Sisowath Monikessan | Disappeared under Khmer Rouge[316] |

| Norodom Sorya Roeungsi | 1947 | 1976 | Sisowath Pongsanmoni | Disappeared under Khmer Rouge[316] |

| Norodom Kantha Bopha | 1948 | 1952 | Sisowath Pongsanmoni | Leukemia[315] |

| Norodom Khemanourak | 1949 | 1975 | Sisowath Pongsanmoni | Disappeared under Khmer Rouge[317] |

| Norodom Botum Bopha | 1951 | 1975 | Sisowath Pongsanmoni | Disappeared under Khmer Rouge[317] |

| Norodom Sujata | 1953 | 1975 | Mam Manivan | Disappeared under Khmer Rouge[317] |

| Norodom Sihamoni | 1953 | Monique Izzi (Monineath) | ||

| Norodom Narindrapong | 1954 | 2003 | Monique Izzi (Monineath) | Heart attack[318] |

| Norodom Arunrasmy | 1955 | Mam Manivan |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Norodom Sihanouk[319] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Jeldres (2005), p. 30.

- Jeldres (2003), p. 58.

- Jeldres (2003), p. 44.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 32.

- Osborne (1994), p. 24

- Jeldres (2005), p. 294.

- Jeldres (2003), p. 54.

- Osborne (1994), p. 30.

- Osborne (1994), p. 37.

- Osborne (1994), p. 42.

- Osborne (1994), p. 43.

- Osborne (1994), p. 45.

- Osborne (1994), p. 48.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 44.

- Osborne (1994), p. 50.

- Osborne (1994), p. 51.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 46.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 206.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 47.

- Chandler (1991), p. 43.

- Chandler (1991), p. 40.

- Chandler (1991), p. 41.

- Chandler (1991), p. 42.

- Osborne (1994), p. 66.

- Osborne (1994), p. 63.

- Chandler (1991), p. 58.

- Chandler (1991), p. 59.

- Chandler (1991), p. 60.

- Chandler (1991), p. 62.

- Chandler (1991), p. 61.

- Osborne (1994), p. 74.

- Osborne (1994), p. 76.

- Jeldres (2003), p. 61.

- Chandler (1991), p. 70.

- Osborne (1994), p. 80.

- Osborne (1994), p. 87.

- Osborne (1994), p. 88.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 52.

- Osborne (1994), p. 89.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 54.

- Chandler (1991), p. 78.

- Osborne (1994), p. 91.

- PRO, FO 371/117124, British Legation Phnom Penh's telegrams 86 and 87 (1955)

- Osborne (1994), p. 93.

- Chandler (1991), p. 79.

- Souvenirs doux et amers, p. 218-19

- Kiernan, B. How Pol Pot came to power, Yale University Press, 2004, p. 158

- Chandler (1991), p. 79.

- Chandler (1991), p. 82.

- Osborne (1994), p. 97.

- Chandler (1991), p. 83.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 55.

- Jeldres (2003), p. 68.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 58.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 59.

- Chandler (1991), p. 87.

- Chandler (1991), p. 91.

- Chandler (1991), pp. 95, 98.

- Osborne (1994), p. 105.

- Chandler (1991), p. 80.

- Burchett (1973), pp. 78–79.

- Chandler (1991), p. 93.

- Osborne (1994), p. 102.

- Chandler (1991), p. 86.

- Osborne (1994), p. 152.

- Chandler (1991), p. 92.

- Chandler (1991), p. 94.

- Chandler (1991), p. 95.

- Chandler (1991), p. 96.

- Burchett (1973), p. 105.

- Chandler (1991), p. 101.

- Osborne (1994), p. 110.

- Burchett (1973), p. 107.

- Burchett (1973), p. 108.

- Chandler (1991), p. 106.

- Burchett (1973), p. 110.

- Osborne (1994), p. 112.

- Chandler (1991), p. 107.

- Osborne (1994), p. 115.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 61.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 62.

- Osborne (1994), p. 120.

- Osborne (1994), p. 144.

- Chandler (1991), p. 119.

- Chandler (1991), p. 120.

- Osborne (1994), p. 157.

- Osborne (1994), p. 158.

- Peou (2000), pp. 125–26.

- Burchett (1973), p. 133.

- Osborne (1994), p. 161.

- Burchett (1973), p. 137.

- Chandler (1991), pp. 136–37.

- Chandler (1991), p. 140.

- Marlay and Neher (1999), p. 160.

- Burchett (1973), p. 139.

- Peou (2000), p. 124.

- Osborne (1994), p. 187.

- Osborne (1994), p. 188.

- Chandler (1991), p. 156.

- Osborne (1994), p. 189.

- Chandler (1991), p. 164.

- Osborne (1994), p. 190.

- Osborne (1994), p. 193.

- Chandler (1991), p. 166.

- Cohen (1968), p. 18.

- Cohen (1968), p. 19.

- Cohen (1968), p. 25.

- Cohen (1968), p. 26.

- Cohen (1968), p. 28.

- Cohen (1968), p. 29.

- Langguth (2000) p.543

- Marlay and Neher (1999), p. 162.

- Osborne (1994), p. 195.

- Clymer 2013, pp. 14–16.

- Langguth (2000) p.543

- Chandler (1991), p. 173.

- Burchett (1973), p. 40.

- Chandler (1991), p. 184.

- Chandler (1991), p. 139.

- Osborne (1994), p. 205.

- Chandler (1991), p. 185.

- Chandler (1991), p. 189.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 70.

- Marlay and Neher (1999), p. 164.

- Langguth (2000) p.557

- Osborne (1994), p. 211.

- Chandler (1991), p. 195.

- Osborne (1994), p. 213.

- Burchett (1973), p. 51.

- Burchett (1973), p. 50.

- Langguth (2000) p.558

- Jeldres (2005), p. 79.

- Osborne (1994), p. 218.

- Langguth (2000) p.559

- Langguth (2000) p.558

- Langguth (2000) p.558

- Osborne (1994), p. 219.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 137.

- Burchett (1973), p. 271.

- Marlay and Neher (1999), p. 167.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 178.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 183.

- Osborne (1994), p. 226.

- Press Staff (18 April 1975). "Cambodians Designate Sihanouk as Chief for Life". New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Osborne (1994), p. 229.

- Marlay and Neher (1999), p. 168.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 191.

- Osborne (1994), p. 231.

- Osborne (1994), p. 232.

- Osborne (1994), p. 233.

- Osborne (1994), p. 238.

- Osborne (1994), p. 234.

- Osborne (1994), p. 240.

- Chandler (1991), p. 311.

- Osborne (1994), p. 242.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 202.

- Jeldres (2005), pp. 205–06.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 207.

- Jeldres (2005), pp. 197–98.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 235.

- Mehta (2001), p. 68.

- Osborne (1994), p. 251.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 236.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 239.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 240.

- Carney, Timothy. Kampuchea in 1982: Political and Military Escalation. p. 80. In Asian Survey, 23:1, 1983.

- Osborne (1994), p. 252.

- Mehta (2001), p. 73.

- Mehta (2001), p. 184.

- Mehta et al. (2013), pp. 154–55.

- Widyono (2008), p. 34.

- Post Staff (29 August 1989). "Final Cambodian talks under way". Lodi News-Sentinel. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- Findlay (1995), p. 8.

- Osborne (1994), p. 255.

- Findlay (1995), p. 7.

- Findlay (1995), p. 9.

- Findlay (1995), p. 12.

- Findlay (1995), p. 15.

- Widyono (2008), p. 142.

- Widyono (2008), pp. 82–83.

- Widyono (2008), p. 84.

- Findlay (1995), p. 46.

- Findlay (1995), p. 86.

- Findlay (1995), pp. 56–57.

- Findlay (1995), pp. 2, 84.

- Widyono (2008), p. 124.

- Widyono (2008), p. 125.

- Findlay (1995), p. 93.

- Mehta et al. (2013), p. 231.

- Widyono (2008), p. 129.

- Osborne (1994), p. 261.

- Widyono (2008), p. 161.

- Findlay (1995), p. 97.

- Jeldres (2003), p. 11.

- Widyono (2008), pp. 1844–45.

- Mehta et al. (2013), p. 232.

- Peou (2000), p. 220.

- Peou (2000), p. 221.

- Mehta et al. (2013), p. 233.

- Widyono (2008), p. 162.

- Peou (2000), p. 222.

- Widyono (2008), p. 163.

- Peou (2000), p. 223.

- Peou (2000), p. 225.

- Mehta et al. (2013), p. 246.