Boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. Produced entirely by cosmic ray spallation and supernovae and not by stellar nucleosynthesis, it is a low-abundance element in the Solar System and in the Earth's crust.[11] It constitutes about 0.001 percent by weight of Earth's crust.[12] Boron is concentrated on Earth by the water-solubility of its more common naturally occurring compounds, the borate minerals. These are mined industrially as evaporites, such as borax and kernite. The largest known boron deposits are in Turkey, the largest producer of boron minerals.

boron (β-rhombohedral)[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Boron | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈbɔːrɒn/ | |||||||||||||||

| Allotropes | α-, β-rhombohedral, β-tetragonal (and more) | |||||||||||||||

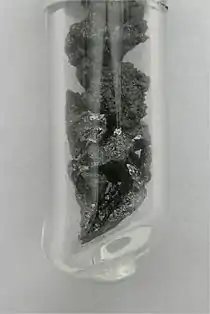

| Appearance | black-brown | |||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar, std(B) | [10.806, 10.821] conventional: 10.81 | |||||||||||||||

| Boron in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 5 | |||||||||||||||

| Group | group 13 (boron group) | |||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s2 2p1 | |||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 2349 K (2076 °C, 3769 °F) | |||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 4200 K (3927 °C, 7101 °F) | |||||||||||||||

| Density when liquid (at m.p.) | 2.08 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 50.2 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 508 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 11.087 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −5, −1, 0,[2] +1, +2, +3[3][4] (a mildly acidic oxide) | |||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.04 | |||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 90 pm | |||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 84±3 pm | |||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 192 pm | |||||||||||||||

Color lines in a spectral range | ||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||

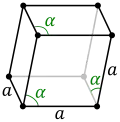

| Crystal structure | rhombohedral | |||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 16,200 m/s (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | β form: 5–7 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C)[5] | |||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 27.4 W/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | ~106 Ω·m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[6] | |||||||||||||||

| Magnetic susceptibility | −6.7·10−6 cm3/mol[6] | |||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | ~9.5 | |||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-42-8 | |||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Louis Jacques Thénard[7] (30 June 1808) | |||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Humphry Davy[8] (9 July 1808) | |||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of boron | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| 10B content is 19.1–20.3% in natural samples, with the remainder being 11B.[10] | ||||||||||||||||

Elemental boron is a metalloid that is found in small amounts in meteoroids but chemically uncombined boron is not otherwise found naturally on Earth. Industrially, very pure boron is produced with difficulty because of refractory contamination by carbon or other elements. Several allotropes of boron exist: amorphous boron is a brown powder; crystalline boron is silvery to black, extremely hard (about 9.5 on the Mohs scale), and a poor electrical conductor at room temperature. The primary use of elemental boron is as boron filaments with applications similar to carbon fibers in some high-strength materials.

Boron is primarily used in chemical compounds. About half of all boron consumed globally is an additive in fiberglass for insulation and structural materials. The next leading use is in polymers and ceramics in high-strength, lightweight structural and refractory materials. Borosilicate glass is desired for its greater strength and thermal shock resistance than ordinary soda lime glass. Boron as sodium perborate is used as a bleach. A small amount of boron is used as a dopant in semiconductors, and reagent intermediates in the synthesis of organic fine chemicals. A few boron-containing organic pharmaceuticals are used or are in study. Natural boron is composed of two stable isotopes, one of which (boron-10) has a number of uses as a neutron-capturing agent.

In biology, borates have low toxicity in mammals (similar to table salt), but are more toxic to arthropods and are used as insecticides. Boric acid is mildly antimicrobial, and several natural boron-containing organic antibiotics are known.[13] Boron is an essential plant nutrient and boron compounds such as borax and boric acid are used as fertilizers in agriculture, although it's only required in small amounts, with excess being toxic. Boron compounds play a strengthening role in the cell walls of all plants. There is no consensus on whether boron is an essential nutrient for mammals, including humans, although there is some evidence it supports bone health.

History

The word boron was coined from borax, the mineral from which it was isolated, by analogy with carbon, which boron resembles chemically.

Borax, its mineral form then known as tincal, glazes were used in China from AD 300, and some crude borax reached the West, where the alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān apparently mentioned it in AD 700. Marco Polo brought some glazes back to Italy in the 13th century. Agricola, around 1600, reports the use of borax as a flux in metallurgy. In 1777, boric acid was recognized in the hot springs (soffioni) near Florence, Italy, and became known as sal sedativum, with primarily medical uses. The rare mineral is called sassolite, which is found at Sasso, Italy. Sasso was the main source of European borax from 1827 to 1872, when American sources replaced it.[14][15] Boron compounds were relatively rarely used until the late 1800s when Francis Marion Smith's Pacific Coast Borax Company first popularized and produced them in volume at low cost.[16]

Boron was not recognized as an element until it was isolated by Sir Humphry Davy[8] and by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Louis Jacques Thénard.[7] In 1808 Davy observed that electric current sent through a solution of borates produced a brown precipitate on one of the electrodes. In his subsequent experiments, he used potassium to reduce boric acid instead of electrolysis. He produced enough boron to confirm a new element and named the element boracium.[8] Gay-Lussac and Thénard used iron to reduce boric acid at high temperatures. By oxidizing boron with air, they showed that boric acid is an oxidation product of boron.[7][17] Jöns Jacob Berzelius identified boron as an element in 1824.[18] Pure boron was arguably first produced by the American chemist Ezekiel Weintraub in 1909.[19][20][21]

Preparation of elemental boron in the laboratory

The earliest routes to elemental boron involved the reduction of boric oxide with metals such as magnesium or aluminium. However, the product is almost always contaminated with borides of those metals. Pure boron can be prepared by reducing volatile boron halides with hydrogen at high temperatures. Ultrapure boron for use in the semiconductor industry is produced by the decomposition of diborane at high temperatures and then further purified by the zone melting or Czochralski processes.[22]

The production of boron compounds does not involve the formation of elemental boron, but exploits the convenient availability of borates.

Characteristics

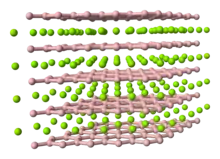

Allotropes

Boron is similar to carbon in its capability to form stable covalently bonded molecular networks. Even nominally disordered (amorphous) boron contains regular boron icosahedra which are, however, bonded randomly to each other without long-range order.[23][24] Crystalline boron is a very hard, black material with a melting point of above 2000 °C. It forms four major polymorphs: α-rhombohedral and β-rhombohedral (α-R and β-R), γ and β-tetragonal (β-T); α-tetragonal phase also exists (α-T), but is very difficult to produce without significant contamination. Most of the phases are based on B12 icosahedra, but the γ-phase can be described as a rocksalt-type arrangement of the icosahedra and B2 atomic pairs.[25] It can be produced by compressing other boron phases to 12–20 GPa and heating to 1500–1800 °C; it remains stable after releasing the temperature and pressure. The T phase is produced at similar pressures, but higher temperatures of 1800–2200 °C. As to the α and β phases, they might both coexist at ambient conditions with the β phase being more stable.[25][26][27] Compressing boron above 160 GPa produces a boron phase with an as yet unknown structure, and this phase is a superconductor at temperatures 6–12 K.[28] Borospherene (fullerene-like B40) molecules) and borophene (proposed graphene-like structure) have been described in 2014.

| Boron phase | α-R | β-R | γ | β-T |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | Rhombohedral | Rhombohedral | Orthorhombic | Tetragonal |

| Atoms/unit cell[25] | 12 | ~105 | 28 | |

| Density (g/cm3)[29][30][31][32] | 2.46 | 2.35 | 2.52 | 2.36 |

| Vickers hardness (GPa)[33][34] | 42 | 45 | 50–58 | |

| Bulk modulus (GPa)[34][35] | 185 | 224 | 227 | |

| Bandgap (eV)[34][36] | 2 | 1.6 | 2.1 |

Chemistry of the element

Elemental boron is rare and poorly studied because the pure material is extremely difficult to prepare. Most studies of "boron" involve samples that contain small amounts of carbon. The chemical behavior of boron resembles that of silicon more than aluminium. Crystalline boron is chemically inert and resistant to attack by boiling hydrofluoric or hydrochloric acid. When finely divided, it is attacked slowly by hot concentrated hydrogen peroxide, hot concentrated nitric acid, hot sulfuric acid or hot mixture of sulfuric and chromic acids.[20]

The rate of oxidation of boron depends on the crystallinity, particle size, purity and temperature. Boron does not react with air at room temperature, but at higher temperatures it burns to form boron trioxide:[37]

- 4 B + 3 O2 → 2 B2O3

Boron undergoes halogenation to give trihalides; for example,

- 2 B + 3 Br2 → 2 BBr3

The trichloride in practice is usually made from the oxide.[37]

Atomic structure

Boron is the lightest element having an electron in a p-orbital in its ground state. But, unlike most other p-elements, it rarely obeys the octet rule and usually places only six electrons[38] (in three molecular orbitals) onto its valence shell. Boron is the prototype for the boron group (the IUPAC group 13), although the other members of this group are metals and more typical p-elements (only aluminium to some extent shares boron's aversion to the octet rule).

Chemical compounds

In the most familiar compounds, boron has the formal oxidation state III. These include oxides, sulfides, nitrides, and halides.[37]

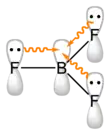

The trihalides adopt a planar trigonal structure. These compounds are Lewis acids in that they readily form adducts with electron-pair donors, which are called Lewis bases. For example, fluoride (F−) and boron trifluoride (BF3) combined to give the tetrafluoroborate anion, BF4−. Boron trifluoride is used in the petrochemical industry as a catalyst. The halides react with water to form boric acid.[37]

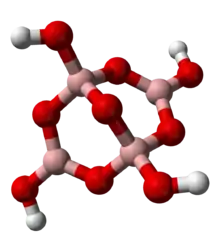

Boron is found in nature on Earth almost entirely as various oxides of B(III), often associated with other elements. More than one hundred borate minerals contain boron in oxidation state +3. These minerals resemble silicates in some respect, although boron is often found not only in a tetrahedral coordination with oxygen, but also in a trigonal planar configuration. Unlike silicates, the boron minerals never contain boron with coordination number greater than four. A typical motif is exemplified by the tetraborate anions of the common mineral borax, shown at left. The formal negative charge of the tetrahedral borate center is balanced by metal cations in the minerals, such as the sodium (Na+) in borax.[37] The tourmaline group of borate-silicates is also a very important boron-bearing mineral group, and a number of borosilicates are also known to exist naturally.[39]

Boranes are chemical compounds of boron and hydrogen, with the generic formula of BxHy. These compounds do not occur in nature. Many of the boranes readily oxidise on contact with air, some violently. The parent member BH3 is called borane, but it is known only in the gaseous state, and dimerises to form diborane, B2H6. The larger boranes all consist of boron clusters that are polyhedral, some of which exist as isomers. For example, isomers of B20H26 are based on the fusion of two 10-atom clusters.

The most important boranes are diborane B2H6 and two of its pyrolysis products, pentaborane B5H9 and decaborane B10H14. A large number of anionic boron hydrides are known, e.g. [B12H12]2−.

The formal oxidation number in boranes is positive, and is based on the assumption that hydrogen is counted as −1 as in active metal hydrides. The mean oxidation number for the borons is then simply the ratio of hydrogen to boron in the molecule. For example, in diborane B2H6, the boron oxidation state is +3, but in decaborane B10H14, it is 7/5 or +1.4. In these compounds the oxidation state of boron is often not a whole number.

The boron nitrides are notable for the variety of structures that they adopt. They exhibit structures analogous to various allotropes of carbon, including graphite, diamond, and nanotubes. In the diamond-like structure, called cubic boron nitride (tradename Borazon), boron atoms exist in the tetrahedral structure of carbons atoms in diamond, but one in every four B-N bonds can be viewed as a coordinate covalent bond, wherein two electrons are donated by the nitrogen atom which acts as the Lewis base to a bond to the Lewis acidic boron(III) centre. Cubic boron nitride, among other applications, is used as an abrasive, as it has a hardness comparable with diamond (the two substances are able to produce scratches on each other). In the BN compound analogue of graphite, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), the positively charged boron and negatively charged nitrogen atoms in each plane lie adjacent to the oppositely charged atom in the next plane. Consequently, graphite and h-BN have very different properties, although both are lubricants, as these planes slip past each other easily. However, h-BN is a relatively poor electrical and thermal conductor in the planar directions.[40][41]

Organoboron chemistry

A large number of organoboron compounds are known and many are useful in organic synthesis. Many are produced from hydroboration, which employs diborane, B2H6, a simple borane chemical. Organoboron(III) compounds are usually tetrahedral or trigonal planar, for example, tetraphenylborate, [B(C6H5)4]− vs. triphenylborane, B(C6H5)3. However, multiple boron atoms reacting with each other have a tendency to form novel dodecahedral (12-sided) and icosahedral (20-sided) structures composed completely of boron atoms, or with varying numbers of carbon heteroatoms.

Organoboron chemicals have been employed in uses as diverse as boron carbide (see below), a complex very hard ceramic composed of boron-carbon cluster anions and cations, to carboranes, carbon-boron cluster chemistry compounds that can be halogenated to form reactive structures including carborane acid, a superacid. As one example, carboranes form useful molecular moieties that add considerable amounts of boron to other biochemicals in order to synthesize boron-containing compounds for boron neutron capture therapy for cancer.

Compounds of B(I) and B(II)

Although these are not found on Earth naturally, boron forms a variety of stable compounds with formal oxidation state less than three. As for many covalent compounds, formal oxidation states are often of little meaning in boron hydrides and metal borides. The halides also form derivatives of B(I) and B(II). BF, isoelectronic with N2, cannot be isolated in condensed form, but B2F4 and B4Cl4 are well characterized.[42]

Binary metal-boron compounds, the metal borides, contain boron in negative oxidation states. Illustrative is magnesium diboride (MgB2). Each boron atom has a formal −1 charge and magnesium is assigned a formal charge of +2. In this material, the boron centers are trigonal planar with an extra double bond for each boron, forming sheets akin to the carbon in graphite. However, unlike hexagonal boron nitride, which lacks electrons in the plane of the covalent atoms, the delocalized electrons in magnesium diboride allow it to conduct electricity similar to isoelectronic graphite. In 2001, this material was found to be a high-temperature superconductor.[43][44] It is a superconductor under active development. A project at CERN to make MgB2 cables has resulted in superconducting test cables able to carry 20,000 amperes for extremely high current distribution applications, such as the contemplated high luminosity version of the large hadron collider.[45]

Certain other metal borides find specialized applications as hard materials for cutting tools.[46] Often the boron in borides has fractional oxidation states, such as −1/3 in calcium hexaboride (CaB6).

From the structural perspective, the most distinctive chemical compounds of boron are the hydrides. Included in this series are the cluster compounds dodecaborate (B

12H2−

12), decaborane (B10H14), and the carboranes such as C2B10H12. Characteristically such compounds contain boron with coordination numbers greater than four.[37]

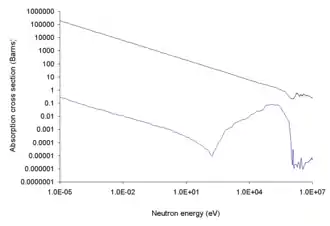

Isotopes

Boron has two naturally occurring and stable isotopes, 11B (80.1%) and 10B (19.9%). The mass difference results in a wide range of δ11B values, which are defined as a fractional difference between the 11B and 10B and traditionally expressed in parts per thousand, in natural waters ranging from −16 to +59. There are 13 known isotopes of boron, the shortest-lived isotope is 7B which decays through proton emission and alpha decay. It has a half-life of 3.5×10−22 s. Isotopic fractionation of boron is controlled by the exchange reactions of the boron species B(OH)3 and [B(OH)4]−. Boron isotopes are also fractionated during mineral crystallization, during H2O phase changes in hydrothermal systems, and during hydrothermal alteration of rock. The latter effect results in preferential removal of the [10B(OH)4]− ion onto clays. It results in solutions enriched in 11B(OH)3 and therefore may be responsible for the large 11B enrichment in seawater relative to both oceanic crust and continental crust; this difference may act as an isotopic signature.[47]

The exotic 17B exhibits a nuclear halo, i.e. its radius is appreciably larger than that predicted by the liquid drop model.[48]

The 10B isotope is useful for capturing thermal neutrons (see neutron cross section#Typical cross sections). The nuclear industry enriches natural boron to nearly pure 10B. The less-valuable by-product, depleted boron, is nearly pure 11B.

Commercial isotope enrichment

Because of its high neutron cross-section, boron-10 is often used to control fission in nuclear reactors as a neutron-capturing substance.[49] Several industrial-scale enrichment processes have been developed; however, only the fractionated vacuum distillation of the dimethyl ether adduct of boron trifluoride (DME-BF3) and column chromatography of borates are being used.[50][51]

Enriched boron (boron-10)

Enriched boron or 10B is used in both radiation shielding and is the primary nuclide used in neutron capture therapy of cancer. In the latter ("boron neutron capture therapy" or BNCT), a compound containing 10B is incorporated into a pharmaceutical which is selectively taken up by a malignant tumor and tissues near it. The patient is then treated with a beam of low energy neutrons at a relatively low neutron radiation dose. The neutrons, however, trigger energetic and short-range secondary alpha particle and lithium-7 heavy ion radiation that are products of the boron + neutron nuclear reaction, and this ion radiation additionally bombards the tumor, especially from inside the tumor cells.[52][53][54][55]

In nuclear reactors, 10B is used for reactivity control and in emergency shutdown systems. It can serve either function in the form of borosilicate control rods or as boric acid. In pressurized water reactors, 10B boric acid is added to the reactor coolant when the plant is shut down for refueling. It is then slowly filtered out over many months as fissile material is used up and the fuel becomes less reactive.[56]

In future manned interplanetary spacecraft, 10B has a theoretical role as structural material (as boron fibers or BN nanotube material) which would also serve a special role in the radiation shield. One of the difficulties in dealing with cosmic rays, which are mostly high energy protons, is that some secondary radiation from interaction of cosmic rays and spacecraft materials is high energy spallation neutrons. Such neutrons can be moderated by materials high in light elements, such as polyethylene, but the moderated neutrons continue to be a radiation hazard unless actively absorbed in the shielding. Among light elements that absorb thermal neutrons, 6Li and 10B appear as potential spacecraft structural materials which serve both for mechanical reinforcement and radiation protection.[57]

Radiation-hardened semiconductors

Cosmic radiation will produce secondary neutrons if it hits spacecraft structures. Those neutrons will be captured in 10B, if it is present in the spacecraft's semiconductors, producing a gamma ray, an alpha particle, and a lithium ion. Those resultant decay products may then irradiate nearby semiconductor "chip" structures, causing data loss (bit flipping, or single event upset). In radiation-hardened semiconductor designs, one countermeasure is to use depleted boron, which is greatly enriched in 11B and contains almost no 10B. This is useful because 11B is largely immune to radiation damage. Depleted boron is a byproduct of the nuclear industry.[56]

Proton-boron fusion

11B is also a candidate as a fuel for aneutronic fusion. When struck by a proton with energy of about 500 keV, it produces three alpha particles and 8.7 MeV of energy. Most other fusion reactions involving hydrogen and helium produce penetrating neutron radiation, which weakens reactor structures and induces long-term radioactivity, thereby endangering operating personnel. However, the alpha particles from 11B fusion can be turned directly into electric power, and all radiation stops as soon as the reactor is turned off.[58]

NMR spectroscopy

Both 10B and 11B possess nuclear spin. The nuclear spin of 10B is 3 and that of 11B is 3/2. These isotopes are, therefore, of use in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy; and spectrometers specially adapted to detecting the boron-11 nuclei are available commercially. The 10B and 11B nuclei also cause splitting in the resonances of attached nuclei.[59]

Occurrence

Boron is rare in the Universe and solar system due to trace formation in the Big Bang and in stars. It is formed in minor amounts in cosmic ray spallation nucleosynthesis and may be found uncombined in cosmic dust and meteoroid materials.

In the high oxygen environment of Earth, boron is always found fully oxidized to borate. Boron does not appear on Earth in elemental form. Extremely small traces of elemental boron were detected in Lunar regolith.[60][61]

Although boron is a relatively rare element in the Earth's crust, representing only 0.001% of the crust mass, it can be highly concentrated by the action of water, in which many borates are soluble. It is found naturally combined in compounds such as borax and boric acid (sometimes found in volcanic spring waters). About a hundred borate minerals are known.

On September 5, 2017, scientists reported that the Curiosity rover detected boron, an essential ingredient for life on Earth, on the planet Mars. Such a finding, along with previous discoveries that water may have been present on ancient Mars, further supports the possible early habitability of Gale Crater on Mars.[62][63]

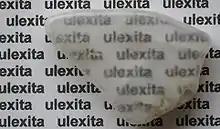

Production

Economically important sources of boron are the minerals colemanite, rasorite (kernite), ulexite and tincal. Together these constitute 90% of mined boron-containing ore. The largest global borax deposits known, many still untapped, are in Central and Western Turkey, including the provinces of Eskişehir, Kütahya and Balıkesir.[64][65][66] Global proven boron mineral mining reserves exceed one billion metric tonnes, against a yearly production of about four million tonnes.[67]

Turkey and the United States are the largest producers of boron products. Turkey produces about half of the global yearly demand, through Eti Mine Works (Turkish: Eti Maden İşletmeleri) a Turkish state-owned mining and chemicals company focusing on boron products. It holds a government monopoly on the mining of borate minerals in Turkey, which possesses 72% of the world's known deposits.[68] In 2012, it held a 47% share of production of global borate minerals, ahead of its main competitor, Rio Tinto Group.[69]

Almost a quarter (23%) of global boron production comes from the single Rio Tinto Borax Mine (also known as the U.S. Borax Boron Mine) 35°2′34.447″N 117°40′45.412″W near Boron, California.[70][71]

Market trend

The average cost of crystalline boron is $5/g.[72] Free boron is chiefly used in making boron fibers, where it is deposited by chemical vapor deposition on a tungsten core (see below). Boron fibers are used in lightweight composite applications, such as high strength tapes. This use is a very small fraction of total boron use. Boron is introduced into semiconductors as boron compounds, by ion implantation.

Estimated global consumption of boron (almost entirely as boron compounds) was about 4 million tonnes of B2O3 in 2012. Boron mining and refining capacities are considered to be adequate to meet expected levels of growth through the next decade.

The form in which boron is consumed has changed in recent years. The use of ores like colemanite has declined following concerns over arsenic content. Consumers have moved toward the use of refined borates and boric acid that have a lower pollutant content.

Increasing demand for boric acid has led a number of producers to invest in additional capacity. Turkey's state-owned Eti Mine Works opened a new boric acid plant with the production capacity of 100,000 tonnes per year at Emet in 2003. Rio Tinto Group increased the capacity of its boron plant from 260,000 tonnes per year in 2003 to 310,000 tonnes per year by May 2005, with plans to grow this to 366,000 tonnes per year in 2006. Chinese boron producers have been unable to meet rapidly growing demand for high quality borates. This has led to imports of sodium tetraborate (borax) growing by a hundredfold between 2000 and 2005 and boric acid imports increasing by 28% per year over the same period.[73][74]

The rise in global demand has been driven by high growth rates in glass fiber, fiberglass and borosilicate glassware production. A rapid increase in the manufacture of reinforcement-grade boron-containing fiberglass in Asia, has offset the development of boron-free reinforcement-grade fiberglass in Europe and the US. The recent rises in energy prices may lead to greater use of insulation-grade fiberglass, with consequent growth in the boron consumption. Roskill Consulting Group forecasts that world demand for boron will grow by 3.4% per year to reach 21 million tonnes by 2010. The highest growth in demand is expected to be in Asia where demand could rise by an average 5.7% per year.[73][75]

Applications

Nearly all boron ore extracted from the Earth is destined for refinement into boric acid and sodium tetraborate pentahydrate. In the United States, 70% of the boron is used for the production of glass and ceramics.[76][77] The major global industrial-scale use of boron compounds (about 46% of end-use) is in production of glass fiber for boron-containing insulating and structural fiberglasses, especially in Asia. Boron is added to the glass as borax pentahydrate or boron oxide, to influence the strength or fluxing qualities of the glass fibers.[78] Another 10% of global boron production is for borosilicate glass as used in high strength glassware. About 15% of global boron is used in boron ceramics, including super-hard materials discussed below. Agriculture consumes 11% of global boron production, and bleaches and detergents about 6%.[79]

Elemental boron fiber

Boron fibers (boron filaments) are high-strength, lightweight materials that are used chiefly for advanced aerospace structures as a component of composite materials, as well as limited production consumer and sporting goods such as golf clubs and fishing rods.[80][81] The fibers can be produced by chemical vapor deposition of boron on a tungsten filament.[82][83]

Boron fibers and sub-millimeter sized crystalline boron springs are produced by laser-assisted chemical vapor deposition. Translation of the focused laser beam allows production of even complex helical structures. Such structures show good mechanical properties (elastic modulus 450 GPa, fracture strain 3.7%, fracture stress 17 GPa) and can be applied as reinforcement of ceramics or in micromechanical systems.[84]

Boronated fiberglass

Fiberglass is a fiber reinforced polymer made of plastic reinforced by glass fibers, commonly woven into a mat. The glass fibers used in the material are made of various types of glass depending upon the fiberglass use. These glasses all contain silica or silicate, with varying amounts of oxides of calcium, magnesium, and sometimes boron. The boron is present as borosilicate, borax, or boron oxide, and is added to increase the strength of the glass, or as a fluxing agent to decrease the melting temperature of silica, which is too high to be easily worked in its pure form to make glass fibers.

The highly boronated glasses used in fiberglass are E-glass (named for "Electrical" use, but now the most common fiberglass for general use). E-glass is alumino-borosilicate glass with less than 1% w/w alkali oxides, mainly used for glass-reinforced plastics. Other common high-boron glasses include C-glass, an alkali-lime glass with high boron oxide content, used for glass staple fibers and insulation, and D-glass, a borosilicate glass, named for its low Dielectric constant).[85]

Not all fiberglasses contain boron, but on a global scale, most of the fiberglass used does contain it. Because the ubiquitous use of fiberglass in construction and insulation, boron-containing fiberglasses consume half the global production of boron, and are the single largest commercial boron market.

Borosilicate glass

Borosilicate glass, which is typically 12–15% B2O3, 80% SiO2, and 2% Al2O3, has a low coefficient of thermal expansion, giving it a good resistance to thermal shock. Schott AG's "Duran" and Owens-Corning's trademarked Pyrex are two major brand names for this glass, used both in laboratory glassware and in consumer cookware and bakeware, chiefly for this resistance.[86]

Boron carbide ceramic

Several boron compounds are known for their extreme hardness and toughness. Boron carbide is a ceramic material which is obtained by decomposing B2O3 with carbon in an electric furnace:

- 2 B2O3 + 7 C → B4C + 6 CO

Boron carbide's structure is only approximately B4C, and it shows a clear depletion of carbon from this suggested stoichiometric ratio. This is due to its very complex structure. The substance can be seen with empirical formula B12C3 (i.e., with B12 dodecahedra being a motif), but with less carbon, as the suggested C3 units are replaced with C-B-C chains, and some smaller (B6) octahedra are present as well (see the boron carbide article for structural analysis). The repeating polymer plus semi-crystalline structure of boron carbide gives it great structural strength per weight. It is used in tank armor, bulletproof vests, and numerous other structural applications.

Boron carbide's ability to absorb neutrons without forming long-lived radionuclides (especially when doped with extra boron-10) makes the material attractive as an absorbent for neutron radiation arising in nuclear power plants.[88] Nuclear applications of boron carbide include shielding, control rods and shut-down pellets. Within control rods, boron carbide is often powdered, to increase its surface area.[89]

High-hardness and abrasive compounds

| Material | Diamond | cubic-BC2N | cubic-BC5 | cubic-BN | B4C | ReB2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vickers hardness (GPa) | 115 | 76 | 71 | 62 | 38 | 22 |

| Fracture toughness (MPa m1⁄2) | 5.3 | 4.5 | 9.5 | 6.8 | 3.5 |

Boron carbide and cubic boron nitride powders are widely used as abrasives. Boron nitride is a material isoelectronic to carbon. Similar to carbon, it has both hexagonal (soft graphite-like h-BN) and cubic (hard, diamond-like c-BN) forms. h-BN is used as a high temperature component and lubricant. c-BN, also known under commercial name borazon,[92] is a superior abrasive. Its hardness is only slightly smaller than, but its chemical stability is superior, to that of diamond. Heterodiamond (also called BCN) is another diamond-like boron compound.

Metallurgy

Boron is added to boron steels at the level of a few parts per million to increase hardenability. Higher percentages are added to steels used in the nuclear industry due to boron's neutron absorption ability.

Boron can also increase the surface hardness of steels and alloys through boriding. Additionally metal borides are used for coating tools through chemical vapor deposition or physical vapor deposition. Implantation of boron ions into metals and alloys, through ion implantation or ion beam deposition, results in a spectacular increase in surface resistance and microhardness. Laser alloying has also been successfully used for the same purpose. These borides are an alternative to diamond coated tools, and their (treated) surfaces have similar properties to those of the bulk boride.[93]

For example, rhenium diboride can be produced at ambient pressures, but is rather expensive because of rhenium. The hardness of ReB2 exhibits considerable anisotropy because of its hexagonal layered structure. Its value is comparable to that of tungsten carbide, silicon carbide, titanium diboride or zirconium diboride.[91] Similarly, AlMgB14 + TiB2 composites possess high hardness and wear resistance and are used in either bulk form or as coatings for components exposed to high temperatures and wear loads.[94]

Detergent formulations and bleaching agents

Borax is used in various household laundry and cleaning products,[95] including the "20 Mule Team Borax" laundry booster and "Boraxo" powdered hand soap. It is also present in some tooth bleaching formulas.[77]

Sodium perborate serves as a source of active oxygen in many detergents, laundry detergents, cleaning products, and laundry bleaches. However, despite its name, "Borateem" laundry bleach no longer contains any boron compounds, using sodium percarbonate instead as a bleaching agent.[96]

Insecticides

Boric acid is used as an insecticide, notably against ants, fleas, and cockroaches.[97]

Semiconductors

Boron is a useful dopant for such semiconductors as silicon, germanium, and silicon carbide. Having one fewer valence electron than the host atom, it donates a hole resulting in p-type conductivity. Traditional method of introducing boron into semiconductors is via its atomic diffusion at high temperatures. This process uses either solid (B2O3), liquid (BBr3), or gaseous boron sources (B2H6 or BF3). However, after the 1970s, it was mostly replaced by ion implantation, which relies mostly on BF3 as a boron source.[98] Boron trichloride gas is also an important chemical in semiconductor industry, however, not for doping but rather for plasma etching of metals and their oxides.[99] Triethylborane is also injected into vapor deposition reactors as a boron source. Examples are the plasma deposition of boron-containing hard carbon films, silicon nitride–boron nitride films, and for doping of diamond film with boron.[100]

Magnets

Boron is a component of neodymium magnets (Nd2Fe14B), which are among the strongest type of permanent magnet. These magnets are found in a variety of electromechanical and electronic devices, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) medical imaging systems, in compact and relatively small motors and actuators. As examples, computer HDDs (hard disk drives), CD (compact disk) and DVD (digital versatile disk) players rely on neodymium magnet motors to deliver intense rotary power in a remarkably compact package. In mobile phones 'Neo' magnets provide the magnetic field which allows tiny speakers to deliver appreciable audio power.[101]

Shielding and neutron absorber in nuclear reactors

Boron shielding is used as a control for nuclear reactors, taking advantage of its high cross-section for neutron capture.[102]

In pressurized water reactors a variable concentration of boronic acid in the cooling water is used as a neutron poison to compensate the variable reactivity of the fuel. When new rods are inserted the concentration of boronic acid is maximal, and is reduced during the lifetime.[103]

Other nonmedical uses

- Because of its distinctive green flame, amorphous boron is used in pyrotechnic flares.[104]

- Starch and casein-based adhesives contain sodium tetraborate decahydrate (Na2B4O7·10 H2O)

- Some anti-corrosion systems contain borax.[105]

- Sodium borates are used as a flux for soldering silver and gold and with ammonium chloride for welding ferrous metals.[106] They are also fire retarding additives to plastics and rubber articles.[107]

- Boric acid (also known as orthoboric acid) H3BO3 is used in the production of textile fiberglass and flat panel displays[77][108] and in many PVAc- and PVOH-based adhesives.

- Triethylborane is a substance which ignites the JP-7 fuel of the Pratt & Whitney J58 turbojet/ramjet engines powering the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird.[109] It was also used to ignite the F-1 Engines on the Saturn V Rocket utilized by NASA's Apollo and Skylab programs from 1967 until 1973. Today SpaceX uses it to ignite the engines on their Falcon 9 rocket.[110] Triethylborane is suitable for this because of its pyrophoric properties, especially the fact that it burns with a very high temperature.[111] Triethylborane is an industrial initiator in radical reactions, where it is effective even at low temperatures.

- Borates are used as environmentally benign wood preservatives.[112]

Pharmaceutical and biological applications

Boric acid has antiseptic, antifungal, and antiviral properties and for these reasons is applied as a water clarifier in swimming pool water treatment.[113] Mild solutions of boric acid have been used as eye antiseptics.

Bortezomib (marketed as Velcade and Cytomib). Boron appears as an active element in its first-approved organic pharmaceutical in the pharmaceutical bortezomib, a new class of drug called the proteasome inhibitors, which are active in myeloma and one form of lymphoma (it is in currently in experimental trials against other types of lymphoma). The boron atom in bortezomib binds the catalytic site of the 26S proteasome[114] with high affinity and specificity.

- A number of potential boronated pharmaceuticals using boron-10, have been prepared for use in boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT).[115]

- Some boron compounds show promise in treating arthritis, though none have as yet been generally approved for the purpose.[116]

Tavaborole (marketed as Kerydin) is an Aminoacyl tRNA synthetase inhibitor which is used to treat toenail fungus. It gained FDA approval in July 2014.[117]

Dioxaborolane chemistry enables radioactive fluoride (18F) labeling of antibodies or red blood cells, which allows for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of cancer[118] and hemorrhages,[119] respectively. A Human-Derived, Genetic, Positron-emitting and Fluorescent (HD-GPF) reporter system uses a human protein, PSMA and non-immunogenic, and a small molecule that is positron-emitting (boron bound 18F) and fluorescent for dual modality PET and fluorescence imaging of genome modified cells, e.g. cancer, CRISPR/Cas9, or CAR T-cells, in an entire mouse.[120]

Research areas

Magnesium diboride is an important superconducting material with the transition temperature of 39 K. MgB2 wires are produced with the powder-in-tube process and applied in superconducting magnets.[121][122]

Amorphous boron is used as a melting point depressant in nickel-chromium braze alloys.[123]

Hexagonal boron nitride forms atomically thin layers, which have been used to enhance the electron mobility in graphene devices.[124][125] It also forms nanotubular structures (BNNTs), which have high strength, high chemical stability, and high thermal conductivity, among its list of desirable properties.[126]

Biological role

Boron is an essential plant nutrient, required primarily for maintaining the integrity of cell walls. However, high soil concentrations of greater than 1.0 ppm lead to marginal and tip necrosis in leaves as well as poor overall growth performance. Levels as low as 0.8 ppm produce these same symptoms in plants that are particularly sensitive to boron in the soil. Nearly all plants, even those somewhat tolerant of soil boron, will show at least some symptoms of boron toxicity when soil boron content is greater than 1.8 ppm. When this content exceeds 2.0 ppm, few plants will perform well and some may not survive.[127][128][129]

It is thought that boron plays several essential roles in animals, including humans, but the exact physiological role is poorly understood.[130][131] A small human trial published in 1987 reported on postmenopausal women first made boron deficient and then repleted with 3 mg/day. Boron supplementation markedly reduced urinary calcium excretion and elevated the serum concentrations of 17 beta-estradiol and testosterone.[132]

The U.S. Institute of Medicine has not confirmed that boron is an essential nutrient for humans, so neither a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) nor an Adequate Intake have been established. Adult dietary intake is estimated at 0.9 to 1.4 mg/day, with about 90% absorbed. What is absorbed is mostly excreted in urine. The Tolerable Upper Intake Level for adults is 20 mg/day.[133]

In 2013, a hypothesis suggested it was possible that boron and molybdenum catalyzed the production of RNA on Mars with life being transported to Earth via a meteorite around 3 billion years ago.[134]

There exist several known boron-containing natural antibiotics. The first one found was boromycin, isolated from streptomyces.[135][136]

Congenital endothelial dystrophy type 2, a rare form of corneal dystrophy, is linked to mutations in SLC4A11 gene that encodes a transporter reportedly regulating the intracellular concentration of boron.[137]

Analytical quantification

For determination of boron content in food or materials, the colorimetric curcumin method is used. Boron is converted to boric acid or borates and on reaction with curcumin in acidic solution, a red colored boron-chelate complex, rosocyanine, is formed.[138]

Health issues and toxicity

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS pictograms |  |

| GHS Signal word | Warning |

| H302[139] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Elemental boron, boron oxide, boric acid, borates, and many organoboron compounds are relatively nontoxic to humans and animals (with toxicity similar to that of table salt). The LD50 (dose at which there is 50% mortality) for animals is about 6 g per kg of body weight. Substances with LD50 above 2 g are considered nontoxic. An intake of 4 g/day of boric acid was reported without incident, but more than this is considered toxic in more than a few doses. Intakes of more than 0.5 grams per day for 50 days cause minor digestive and other problems suggestive of toxicity.[141] Dietary supplementation of boron may be helpful for bone growth, wound healing, and antioxidant activity,[142] and insufficient amount of boron in diet may result in boron deficiency.

Single medical doses of 20 g of boric acid for neutron capture therapy have been used without undue toxicity.

Boric acid is more toxic to insects than to mammals, and is routinely used as an insecticide.[97]

The boranes (boron hydrogen compounds) and similar gaseous compounds are quite poisonous. As usual, boron is not an element that is intrinsically poisonous, but the toxicity of these compounds depends on structure (for another example of this phenomenon, see phosphine).[14][15] The boranes are also highly flammable and require special care when handling. Sodium borohydride presents a fire hazard owing to its reducing nature and the liberation of hydrogen on contact with acid. Boron halides are corrosive.[143]

.jpg.webp)

Boron is necessary for plant growth, but an excess of boron is toxic to plants, and occurs particularly in acidic soil.[144][145] It presents as a yellowing from the tip inwards of the oldest leaves and black spots in barley leaves, but it can be confused with other stresses such as magnesium deficiency in other plants.[146]

See also

References

- Van Setten et al. 2007, pp. 2460–1

- Braunschweig, H.; Dewhurst, R. D.; Hammond, K.; Mies, J.; Radacki, K.; Vargas, A. (2012). "Ambient-Temperature Isolation of a Compound with a Boron-Boron Triple Bond". Science. 336 (6087): 1420–2. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1420B. doi:10.1126/science.1221138. PMID 22700924. S2CID 206540959.

- Zhang, K.Q.; Guo, B.; Braun, V.; Dulick, M.; Bernath, P.F. (1995). "Infrared Emission Spectroscopy of BF and AIF" (PDF). J. Molecular Spectroscopy. 170 (1): 82. Bibcode:1995JMoSp.170...82Z. doi:10.1006/jmsp.1995.1058.

- Melanie Schroeder. Eigenschaften von borreichen Boriden und Scandium-Aluminium-Oxid-Carbiden (PDF) (in German). p. 139.

- Holcombe Jr., C. E.; Smith, D. D.; Lorc, J. D.; Duerlesen, W. K.; Carpenter; D. A. (October 1973). "Physical-Chemical Properties of beta-Rhombohedral Boron". High Temp. Sci. 5 (5): 349–57.

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). CRC Press. p. 4.127. ISBN 9781498754293.

- Gay Lussac, J.L. & Thenard, L.J. (1808). "Sur la décomposition et la recomposition de l'acide boracique". Annales de chimie. 68: 169–174.

- Davy H (1809). "An account of some new analytical researches on the nature of certain bodies, particularly the alkalies, phosphorus, sulphur, carbonaceous matter, and the acids hitherto undecomposed: with some general observations on chemical theory". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 99: 39–104. doi:10.1098/rstl.1809.0005.

- "Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- Szegedi, S.; Váradi, M.; Buczkó, Cs. M.; Várnagy, M.; Sztaricskai, T. (1990). "Determination of boron in glass by neutron transmission method". Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry Letters. 146 (3): 177. doi:10.1007/BF02165219.

- "Q & A: Where does the element Boron come from?". physics.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "Boron". Britannica encyclopedia.

- Irschik H, Schummer D, Gerth K, Höfle G, Reichenbach H (1995). "The tartrolons, new boron-containing antibiotics from a myxobacterium, Sorangium cellulosum". The Journal of Antibiotics. 48 (1): 26–30. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.48.26. PMID 7532644.

- Garrett, Donald E. (1998). Borates: handbook of deposits, processing, properties, and use. Academic Press. pp. 102, 385–386. ISBN 978-0-12-276060-0.

- Calvert, J. B. "Boron". University of Denver. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- Hildebrand, G. H. (1982) "Borax Pioneer: Francis Marion Smith." San Diego: Howell-North Books. p. 267 ISBN 0-8310-7148-6

- Weeks, Mary Elvira (1933). "XII. Other Elements Isolated with the Aid of Potassium and Sodium: Beryllium, Boron, Silicon and Aluminum". The Discovery of the Elements. Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-7661-3872-8.

- Berzelius produced boron by reducing a borofluoride salt; specifically, by heating potassium borofluoride with potassium metal. See: Berzelius, J. (1824) "Undersökning af flusspatssyran och dess märkvärdigaste föreningar" (Part 2) (Investigation of hydrofluoric acid and of its most noteworthy compounds), Kongliga Vetenskaps-Academiens Handlingar (Proceedings of the Royal Science Academy), vol. 12, pp. 46–98; see especially pp. 88ff. Reprinted in German as: Berzelius, J. J. (1824) "Untersuchungen über die Flußspathsäure und deren merkwürdigste Verbindungen", Poggendorff's Annalen der Physik und Chemie, vol. 78, pages 113–150.

- Weintraub, Ezekiel (1910). "Preparation and properties of pure boron". Transactions of the American Electrochemical Society. 16: 165–184.

- Laubengayer, A. W.; Hurd, D. T.; Newkirk, A. E.; Hoard, J. L. (1943). "Boron. I. Preparation and Properties of Pure Crystalline Boron". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 65 (10): 1924–1931. doi:10.1021/ja01250a036.

- Borchert, W.; Dietz, W.; Koelker, H. (1970). "Crystal Growth of Beta–Rhombohedrical Boron". Zeitschrift für Angewandte Physik. 29: 277. OSTI 4098583.

- Berger, L. I. (1996). Semiconductor materials. CRC Press. pp. 37–43. ISBN 978-0-8493-8912-2.

- Delaplane, R.G.; Dahlborg, U.; Graneli, B.; Fischer, P.; Lundstrom, T. (1988). "A neutron diffraction study of amorphous boron". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 104 (2–3): 249–252. Bibcode:1988JNCS..104..249D. doi:10.1016/0022-3093(88)90395-X.

- R.G. Delaplane; Dahlborg, U.; Howells, W.; Lundstrom, T. (1988). "A neutron diffraction study of amorphous boron using a pulsed source". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 106 (1–3): 66–69. Bibcode:1988JNCS..106...66D. doi:10.1016/0022-3093(88)90229-3.

- Oganov, A.R.; Chen J.; Gatti C.; Ma Y.-M.; Yu T.; Liu Z.; Glass C.W.; Ma Y.-Z.; Kurakevych O.O.; Solozhenko V.L. (2009). "Ionic high-pressure form of elemental boron" (PDF). Nature. 457 (7231): 863–867. arXiv:0911.3192. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..863O. doi:10.1038/nature07736. PMID 19182772. S2CID 4412568.

- van Setten M.J.; Uijttewaal M.A.; de Wijs G.A.; de Groot R.A. (2007). "Thermodynamic stability of boron: The role of defects and zero point motion" (PDF). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 (9): 2458–2465. doi:10.1021/ja0631246. PMID 17295480.

- Widom M.; Mihalkovic M. (2008). "Symmetry-broken crystal structure of elemental boron at low temperature". Phys. Rev. B. 77 (6): 064113. arXiv:0712.0530. Bibcode:2008PhRvB..77f4113W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.77.064113. S2CID 27321818.

- Eremets, M. I.; Struzhkin, V. V.; Mao, H.; Hemley, R. J. (2001). "Superconductivity in Boron". Science. 293 (5528): 272–4. Bibcode:2001Sci...293..272E. doi:10.1126/science.1062286. PMID 11452118. S2CID 23001035.

- Wentorf, R. H. Jr (1 January 1965). "Boron: Another Form". Science. 147 (3653): 49–50. Bibcode:1965Sci...147...49W. doi:10.1126/science.147.3653.49. PMID 17799779. S2CID 20539654.

- Hoard, J. L.; Sullenger, D. B.; Kennard, C. H. L.; Hughes, R. E. (1970). "The structure analysis of β-rhombohedral boron". J. Solid State Chem. 1 (2): 268–277. Bibcode:1970JSSCh...1..268H. doi:10.1016/0022-4596(70)90022-8.

- Will, G.; Kiefer, B. (2001). "Electron Deformation Density in Rhombohedral a-Boron". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 627 (9): 2100. doi:10.1002/1521-3749(200109)627:9<2100::AID-ZAAC2100>3.0.CO;2-G.

- Talley, C. P.; LaPlaca, S.; Post, B. (1960). "A new polymorph of boron". Acta Crystallogr. 13 (3): 271–272. doi:10.1107/S0365110X60000613.

- Solozhenko, V. L.; Kurakevych, O. O.; Oganov, A. R. (2008). "On the hardness of a new boron phase, orthorhombic γ-B28". Journal of Superhard Materials. 30 (6): 428–429. arXiv:1101.2959. doi:10.3103/S1063457608060117. S2CID 15066841.

- Zarechnaya, E. Yu.; Dubrovinsky, L.; Dubrovinskaia, N.; Filinchuk, Y.; Chernyshov, D.; Dmitriev, V.; Miyajima, N.; El Goresy, A.; et al. (2009). "Superhard Semiconducting Optically Transparent High Pressure Phase of Boron". Phys. Rev. Lett. 102 (18): 185501. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102r5501Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.185501. PMID 19518885.

- Nelmes, R. J.; Loveday, J. S.; Allan, D. R.; Hull, S.; Hamel, G.; Grima, P.; Hull, S. (1993). "Neutron- and x-ray-diffraction measurements of the bulk modulus of boron". Phys. Rev. B. 47 (13): 7668–7673. Bibcode:1993PhRvB..47.7668N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.47.7668. PMID 10004773.

- Madelung, O., ed. (1983). Landolt-Bornstein, New Series. 17e. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Bor". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 814–864. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- Key, Jessie A. (14 September 2014). "Violations of the Octet Rule". Introductory Chemistry. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- "Mindat.org - Mines, Minerals and More". www.mindat.org.

- Engler, M. (2007). "Hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN) – Applications from Metallurgy to Cosmetics" (PDF). Cfi/Ber. DKG. 84: D25. ISSN 0173-9913.

- Greim, Jochen & Schwetz, Karl A. (2005). "Boron Carbide, Boron Nitride, and Metal Borides". Boron Carbide, Boron Nitride, and Metal Borides, in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH: Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_295.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Jones, Morton E. & Marsh, Richard E. (1954). "The Preparation and Structure of Magnesium Boride, MgB2". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 76 (5): 1434–1436. doi:10.1021/ja01634a089.

- Canfield, Paul C.; Crabtree, George W. (2003). "Magnesium Diboride: Better Late than Never" (PDF). Physics Today. 56 (3): 34–40. Bibcode:2003PhT....56c..34C. doi:10.1063/1.1570770.

- "Category "News+Articles" not found - CERN Document Server". cds.cern.ch.

- Cardarelli, François (2008). "Titanium Diboride". Materials handbook: A concise desktop reference. pp. 638–639. ISBN 978-1-84628-668-1.

- Barth, S. (1997). "Boron isotopic analysis of natural fresh and saline waters by negative thermal ionization mass spectrometry". Chemical Geology. 143 (3–4): 255–261. Bibcode:1997ChGeo.143..255B. doi:10.1016/S0009-2541(97)00107-1.

- Liu, Z. (2003). "Two-body and three-body halo nuclei". Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy. 46 (4): 441. Bibcode:2003ScChG..46..441L. doi:10.1360/03yw0027. S2CID 121922481.

- Steinbrück, Martin (2004). "Results of the B4C Control Rod Test QUENCH-07" (PDF). Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe in der Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- "Commissioning of Boron Enrichment Plant". Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- Aida, Masao; Fujii, Yasuhiko; Okamoto, Makoto (1986). "Chromatographic Enrichment of 10B by Using Weak-Base Anion-Exchange Resin". Separation Science and Technology. 21 (6): 643–654. doi:10.1080/01496398608056140. showing an enrichment from 18% to above 94%.

- Barth, Rolf F. (2003). "A Critical Assessment of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: An Overview". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 62 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1023/A:1023262817500. PMID 12749698. S2CID 31441665.

- Coderre, Jeffrey A.; Morris, G. M. (1999). "The Radiation Biology of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy". Radiation Research. 151 (1): 1–18. Bibcode:1999RadR..151....1C. doi:10.2307/3579742. JSTOR 3579742. PMID 9973079.

- Barth, Rolf F.; S; F (1990). "Boron Neutron Capture Therapy of Cancer". Cancer Research. 50 (4): 1061–1070. PMID 2404588.

- "Boron Neutron Capture Therapy – An Overview". Pharmainfo.net. 22 August 2006. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Duderstadt, James J.; Hamilton, Louis J. (1976). Nuclear Reactor Analysis. Wiley-Interscience. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-471-22363-4.

- Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Elliman, R. G.; Petravic, M. (2006). "Isotopically Enriched 10BN Nanotubes" (PDF). Advanced Materials. 18 (16): 2157–2160. doi:10.1002/adma.200600231. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2008.

- Nevins, W. M. (1998). "A Review of Confinement Requirements for Advanced Fuels". Journal of Fusion Energy. 17 (1): 25–32. Bibcode:1998JFuE...17...25N. doi:10.1023/A:1022513215080. S2CID 118229833.

- "Boron NMR". BRUKER Biospin. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- Mokhov, A.V., Kartashov, P.M., Gornostaeva, T.A., Asadulin, A.A., Bogatikov, O.A., 2013: Complex nanospherulites of zinc oxide and native amorphous boron in the Lunar regolith from Mare Crisium. Doklady Earth Sciences 448(1) 61-63

- Mindat, http://www.mindat.org/min-43412.html

- Gasda, Patrick J.; et al. (5 September 2017). "In situ detection of boron by ChemCam on Mars" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (17): 8739–8748. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.8739G. doi:10.1002/2017GL074480.

- Paoletta, Rae (6 September 2017). "Curiosity Has Discovered Something That Raises More Questions About Life on Mars". Gizmodo. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Kistler, R. B. (1994). "Boron and Borates" (PDF). Industrial Minerals and Rocks (6th ed.): 171–186.

- Zbayolu, G.; Poslu, K. (1992). "Mining and Processing of Borates in Turkey". Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review. 9 (1–4): 245–254. doi:10.1080/08827509208952709.

- Kar, Y.; Şen, Nejdet; Demİrbaş, Ayhan (2006). "Boron Minerals in Turkey, Their Application Areas and Importance for the Country's Economy". Minerals & Energy – Raw Materials Report. 20 (3–4): 2–10. doi:10.1080/14041040500504293.

- Global reserves chart. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- Şebnem Önder; Ayşe Eda Biçer & Işıl Selen Denemeç (September 2013). "Are certain minerals still under state monopoly?" (PDF). Mining Turkey. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Turkey as the global leader in boron export and production" (PDF). European Association of Service Providers for Persons with Disabilities Annual Conference 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- "U.S. Borax Boron Mine". The Center for Land Use Interpretation, Ludb.clui.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- "Boras". Rio Tinto. 10 April 2012. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- "Boron Properties". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- The Economics of Boron (11th ed.). Roskill Information Services, Ltd. 2006. ISBN 978-0-86214-516-3.

- "Raw and Manufactured Materials 2006 Overview". Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Roskill reports: boron". Roskill. Archived from the original on 4 October 2003. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Boron: Statistics and Information". USGS. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- Hammond, C. R. (2004). The Elements, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Discussion of various types of boron addition to glass fibers in fiberglass. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- Global end use of boron in 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2014

- Herring, H. W. (1966). "Selected Mechanical and Physical Properties of Boron Filaments" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Layden, G. K. (1973). "Fracture behaviour of boron filaments". Journal of Materials Science. 8 (11): 1581–1589. Bibcode:1973JMatS...8.1581L. doi:10.1007/BF00754893. S2CID 136959123.

- Kostick, Dennis S. (2006). "Mineral Yearbook: Boron" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Cooke, Theodore F. (1991). "Inorganic Fibers—A Literature Review". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 74 (12): 2959–2978. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1991.tb04289.x.

- Johansson, S.; Schweitz, Jan-Åke; Westberg, Helena; Boman, Mats (1992). "Microfabrication of three-dimensional boron structures by laser chemical processing". Journal of Applied Physics. 72 (12): 5956–5963. Bibcode:1992JAP....72.5956J. doi:10.1063/1.351904.

-

E. Fitzer; et al. (2000). "Fibers, 5. Synthetic Inorganic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_001. ISBN 978-3527306732. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Pfaender, H. G. (1996). Schott guide to glass (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-412-62060-7.

- Zhang F X; Xu F F; Mori T; Liu Q L; Sato A & Tanaka T (2001). "Crystal structure of new rare-earth boron-rich solids: REB28.5C4". J. Alloys Compd. 329 (1–2): 168–172. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(01)01581-X.

- Fabrication and Evaluation of Urania-Alumina Fuel Elements and Boron Carbide Burnable Poison Elements, Wisnyi, L. G. and Taylor, K.M., in "ASTM Special Technical Publication No. 276: Materials in Nuclear Applications", Committee E-10 Staff, American Society for Testing Materials, 1959

- Weimer, Alan W. (1997). Carbide, Nitride and Boride Materials Synthesis and Processing. Chapman & Hall (London, New York). ISBN 978-0-412-54060-8.

- Solozhenko, V. L.; Kurakevych, Oleksandr O.; Le Godec, Yann; Mezouar, Mohamed; Mezouar, Mohamed (2009). "Ultimate Metastable Solubility of Boron in Diamond: Synthesis of Superhard Diamondlike BC5" (PDF). Phys. Rev. Lett. 102 (1): 015506. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102a5506S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.015506. PMID 19257210.

- Qin, Jiaqian; He, Duanwei; Wang, Jianghua; Fang, Leiming; Lei, Li; Li, Yongjun; Hu, Juan; Kou, Zili; Bi, Yan (2008). "Is Rhenium Diboride a Superhard Material?". Advanced Materials. 20 (24): 4780–4783. doi:10.1002/adma.200801471.

- Wentorf, R. H. (1957). "Cubic form of boron nitride". J. Chem. Phys. 26 (4): 956. Bibcode:1957JChPh..26..956W. doi:10.1063/1.1745964.

- Gogotsi, Y. G. & Andrievski, R.A. (1999). Materials Science of Carbides, Nitrides and Borides. Springer. pp. 270. ISBN 978-0-7923-5707-0.

- Schmidt, Jürgen; Boehling, Marian; Burkhardt, Ulrich; Grin, Yuri (2007). "Preparation of titanium diboride TiB2 by spark plasma sintering at slow heating rate". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 8 (5): 376–382. Bibcode:2007STAdM...8..376S. doi:10.1016/j.stam.2007.06.009.

- Record in the Household Products Database of NLM

- Thompson, R. (1974). "Industrial applications of boron compounds". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 39 (4): 547. doi:10.1351/pac197439040547.

- Klotz, J. H.; Moss, J. I.; Zhao, R.; Davis Jr., L. R.; Patterson, R. S. (1994). "Oral toxicity of boric acid and other boron compounds to immature cat fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae)". J. Econ. Entomol. 87 (6): 1534–1536. doi:10.1093/jee/87.6.1534. PMID 7836612.

- May, Gary S.; Spanos, Costas J. (2006). Fundamentals of semiconductor manufacturing and process control. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-0-471-78406-7.

- Sherer, J. Michael (2005). Semiconductor industry: wafer fab exhaust management. CRC Press. pp. 39–60. ISBN 978-1-57444-720-0.

- Zschech, Ehrenfried; Whelan, Caroline & Mikolajick, Thomas (2005). Materials for information technology: devices, interconnects and packaging. Birkhäuser. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-85233-941-8.

- Campbell, Peter (1996). Permanent magnet materials and their application. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-56688-9.

- Martin, James E (2008). Physics for Radiation Protection: A Handbook. pp. 660–661. ISBN 978-3-527-61880-4.

- Pastina, B.; Isabey, J.; Hickel, B. (1999). "The influence of water chemistry on the radiolysis of the primary coolant water in pressurized water reactors". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 264 (3): 309–318. Bibcode:1999JNuM..264..309P. doi:10.1016/S0022-3115(98)00494-2. ISSN 0022-3115.

- Kosanke, B. J.; et al. (2004). Pyrotechnic Chemistry. Journal of Pyrotechnics. p. 419. ISBN 978-1-889526-15-7.

- "Borax Decahydrate". Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- Davies, A. C. (1992). The Science and Practice of Welding: Welding science and technology. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-521-43565-9.

- Horrocks, A.R. & Price, D. (2001). Fire Retardant Materials. Woodhead Publishing Ltd. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-85573-419-7.

- Ide, F. (2003). "Information technology and polymers. Flat panel display". Engineering Materials. 51: 84. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- "Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird". March Field Air Museum. Archived from the original on 4 March 2000. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- Mission Status Center, June 2, 2010, 1905 GMT, SpaceflightNow, accessed 2010-06-02, Quotation: "The flanges will link the rocket with ground storage tanks containing liquid oxygen, kerosene fuel, helium, gaseous nitrogen and the first stage ignitor source called triethylaluminum-triethylborane, better known as TEA-TEB."

- Young, A. (2008). The Saturn V F-1 Engine: Powering Apollo Into History. Springer. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-387-09629-2.

- Carr, J. M.; Duggan, P. J.; Humphrey, D. G.; Platts, J. A.; Tyndall, E. M. (2010). "Wood Protection Properties of Quaternary Ammonium Arylspiroborate Esters Derived from Naphthalene 2,3-Diol, 2,2'-Biphenol and 3-Hydroxy-2-naphthoic Acid". Australian Journal of Chemistry. 63 (10): 1423. doi:10.1071/CH10132.

- "Boric acid". chemicalland21.com.

- Bonvini P; Zorzi E; Basso G; Rosolen A (2007). "Bortezomib-mediated 26S proteasome inhibition causes cell-cycle arrest and induces apoptosis in CD-30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma". Leukemia. 21 (4): 838–42. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404528. PMID 17268529.

- "Overview of neutron capture therapy pharmaceuticals". Pharmainfo.net. 22 August 2006. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Travers, Richard L.; Rennie, George; Newnham, Rex (1990). "Boron and Arthritis: The Results of a Double-blind Pilot Study". Journal of Nutritional Medicine. 1 (2): 127–132. doi:10.3109/13590849009003147.

- Thompson, Cheryl (8 July 2014). "FDA Approves Boron-based Drug to Treat Toenail Fungal Infections". ashp. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- Rodriguez, Erik A.; Wang, Ye; Crisp, Jessica L.; Vera, David R.; Tsien, Roger Y.; Ting, Richard (27 April 2016). "New Dioxaborolane Chemistry Enables [18F]-Positron-Emitting, Fluorescent [18F]-Multimodality Biomolecule Generation from the Solid Phase". Bioconjugate Chemistry. 27 (5): 1390–1399. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00164. PMC 4916912. PMID 27064381.

- Wang, Ye; An, Fei-Fei; Chan, Mark; Friedman, Beth; Rodriguez, Erik A.; Tsien, Roger Y.; Aras, Omer; Ting, Richard (5 January 2017). "18F-positron-emitting/fluorescent labeled erythrocytes allow imaging of internal hemorrhage in a murine intracranial hemorrhage model". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 37 (3): 776–786. doi:10.1177/0271678x16682510. PMC 5363488. PMID 28054494.

- Guo, Hua; Harikrishna, Kommidi; Vedvyas, Yogindra; McCloskey, Jaclyn E; Zhang, Weiqi; Chen, Nandi; Nurili, Fuad; Wu, Amy P; Sayman, Haluk B. (23 May 2019). "A fluorescent, [ 18 F]-positron-emitting agent for imaging PMSA allows genetic reporting in adoptively-transferred, genetically-modified cells". ACS Chemical Biology. 14 (7): 1449–1459. doi:10.1021/acschembio.9b00160. ISSN 1554-8929. PMC 6775626. PMID 31120734.

- Canfield, Paul C.; Crabtree, George W. (2003). "Magnesium Diboride: Better Late than Never" (PDF). Physics Today. 56 (3): 34–41. Bibcode:2003PhT....56c..34C. doi:10.1063/1.1570770. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- Braccini, Valeria; Nardelli, D.; Penco, R.; Grasso, G. (2007). "Development of ex situ processed MgB2 wires and their applications to magnets". Physica C: Superconductivity. 456 (1–2): 209–217. Bibcode:2007PhyC..456..209B. doi:10.1016/j.physc.2007.01.030.

- Wu, Xiaowei; Chandel, R. S.; Li, Hang (2001). "Evaluation of transient liquid phase bonding between nickel-based superalloys". Journal of Materials Science. 36 (6): 1539–1546. Bibcode:2001JMatS..36.1539W. doi:10.1023/A:1017513200502. S2CID 134252793.

- Dean, C. R.; Young, A. F.; Meric, I.; Lee, C.; Wang, L.; Sorgenfrei, S.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Kim, P.; Shepard, K. L.; Hone, J. (2010). "Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics". Nature Nanotechnology. 5 (10): 722–726. arXiv:1005.4917. Bibcode:2010NatNa...5..722D. doi:10.1038/nnano.2010.172. PMID 20729834. S2CID 1493242.

- Gannett, W.; Regan, W.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Crommie, M. F.; Zettl, A. (2010). "Boron nitride substrates for high mobility chemical vapor deposited graphene". Applied Physics Letters. 98 (24): 242105. arXiv:1105.4938. Bibcode:2011ApPhL..98x2105G. doi:10.1063/1.3599708. S2CID 94765088.

- Zettl, Alex; Cohen, Marvin (2010). "The physics of boron nitride nanotubes". Physics Today. 63 (11): 34–38. Bibcode:2010PhT....63k..34C. doi:10.1063/1.3518210. S2CID 19773801.

- Mahler, R. L. "Essential Plant Micronutrients. Boron in Idaho" (PDF). University of Idaho. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Functions of Boron in Plant Nutrition" (PDF). U.S. Borax Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2009.

- Blevins, Dale G.; Lukaszewski, K. M. (1998). "Functions of Boron in Plant Nutrition". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 49: 481–500. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.481. PMID 15012243.

- "Boron". PDRhealth. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- Nielsen, Forrest H. (1998). "Ultratrace elements in nutrition: Current knowledge and speculation". The Journal of Trace Elements in Experimental Medicine. 11 (2–3): 251–274. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-670X(1998)11:2/3<251::AID-JTRA15>3.0.CO;2-Q.

- Nielsen FH, Hunt CD, Mullen LM, Hunt JR (1987). "Effect of dietary boron on mineral, estrogen, and testosterone metabolism in postmenopausal women". FASEB J. 1 (5): 394–7. doi:10.1096/fasebj.1.5.3678698. PMID 3678698. S2CID 93497977.

- Boron. IN: Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Copper. National Academy Press. 2001, PP. 510–521.

- "Primordial broth of life was a dry Martian cup-a-soup". New Scientist. 29 August 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Hütter, R.; Keller-Schien, W.; Knüsel, F.; Prelog, V.; Rodgers Jr., G. C.; Suter, P.; Vogel, G.; Voser, W.; Zähner, H. (1967). "Stoffwechselprodukte von Mikroorganismen. 57. Mitteilung. Boromycin". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 50 (6): 1533–1539. doi:10.1002/hlca.19670500612. PMID 6081908.

- Dunitz, J. D.; Hawley, D. M.; Miklos, D.; White, D. N. J.; Berlin, Y.; Marusić, R.; Prelog, V. (1971). "Structure of boromycin". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 54 (6): 1709–1713. doi:10.1002/hlca.19710540624. PMID 5131791.

- Vithana, En; Morgan, P; Sundaresan, P; Ebenezer, Nd; Tan, Dt; Mohamed, Md; Anand, S; Khine, Ko; Venkataraman, D; Yong, Vh; Salto-Tellez, M; Venkatraman, A; Guo, K; Hemadevi, B; Srinivasan, M; Prajna, V; Khine, M; Casey, Jr.; Inglehearn, Cf; Aung, T (July 2006). "Mutations in sodium-borate cotransporter SLC4A11 cause recessive congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED2)". Nature Genetics. 38 (7): 755–7. doi:10.1038/ng1824. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 16767101. S2CID 11112294.

- Silverman, L.; Trego, Katherine (1953). "Corrections-Colorimetric Microdetermination of Boron By The Curcumin-Acetone Solution Method". Anal. Chem. 25 (11): 1639. doi:10.1021/ac60083a061.

- "Boron 266620". Sigma-Aldrich.

- "MSDS - 266620". www.sigmaaldrich.com.

- Nielsen, Forrest H. (1997). "Boron in human and animal nutrition". Plant and Soil. 193 (2): 199–208. doi:10.1023/A:1004276311956. S2CID 12163109. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Pizzorno, L (August 2015). "Nothing boring about boron". Integrative Medicine. 14 (4): 35–48. PMC 4712861. PMID 26770156.

- "Environmental Health Criteria 204: Boron". the IPCS. 1998. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- Zekri, Mongi; Obreza, Tom. "Boron (B) and Chlorine (Cl) for Citrus Trees" (PDF). IFAS Extension. University of Florida. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- K. I. Peverill; L. A. Sparrow; Douglas J. Reuter (1999). Soil Analysis: An Interpretation Manual. Csiro Publishing. pp. 309–311. ISBN 978-0-643-06376-1.

- M. P. Reynolds (2001). Application of Physiology in Wheat Breeding. CIMMYT. p. 225. ISBN 978-970-648-077-4.

External links

- Boron at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- J. B. Calvert: Boron, 2004, private website (archived version)