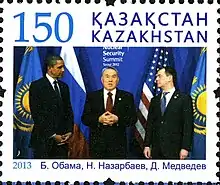

Nursultan Nazarbayev

Nursultan Äbishuly Nazarbayev (Kazakh pronunciation: [nʊrsʊlˈtɑn æbəɕʊˈlə nɑzɑɾˈbɑjɪf][2][note 2]; Kazakh: Нұрсұлтан Әбішұлы Назарбаев, Nursultan Äbişuly Nazarbaev; born 6 July 1940) is a Kazakh politician currently serving as the Chairman of the Security Council of Kazakhstan who previously served as the first President of Kazakhstan, in office from 24 April 1990[3] until his formal resignation on 19 March 2019.[4] He is one of the longest-ruling non-royal leaders in the world, having ruled Kazakhstan for nearly three decades. He was named First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR in 1989 and was elected as the nation's first president following its independence from the Soviet Union. He holds the title "Leader of the Nation".[5]

Elbasy Nursultan Nazarbayev | |

|---|---|

Нұрсұлтан Назарбаев | |

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Nazarbayev in 2020 | |

| Chairman of the Security Council of Kazakhstan | |

| Assumed office 21 August 1991 | |

| President | Himself Kassym-Jomart Tokayev |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| 1st President of Kazakhstan | |

| In office 24 April 1990[note 1] – 20 March 2019 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Vice President | Yerik Asanbayev (1991–96) |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Kassym-Jomart Tokayev |

| Honorary President of Turkic Council[1] | |

| Assumed office 25 April 2019 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Member of the Constitutional Council | |

| Assumed office 19 March 2019 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Chairman of the Assembly of People | |

| Assumed office 1 March 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Chairman of Nur Otan | |

| Assumed office 1 March 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| First Secretary of the Central Committee of the QKP | |

| In office 22 June 1989 – 7 September 1991 | |

| Preceded by | Gennady Kolbin |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Kazakh SSR | |

| In office 22 February 1990 – 24 April 1990 | |

| Prime Minister | Uzakbay Karamanov |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Kazakh SSR | |

| In office 22 March 1984 – 27 July 1989 | |

| Chairman | Bayken Ashimov Salamay Mukashev Zakash Kamaledinov Vera Sidorova Makhtay Sagdiyev |

| Preceded by | Kilibay Medeubekov |

| Succeeded by | Yerik Asanbayev |

| Preceded by | Bayken Ashimov |

| Succeeded by | Uzakbay Karamanov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nursultan Ábishuly Nazarbayev 6 July 1940 Chemolgan, Kazakh SSR, Soviet Union (now Ushkonyr, Kazakhstan) |

| Political party | Nur Otan (1999–present) |

| Other political affiliations | Communist (1962–1991) Independent (1991–1999) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Dariga Dinara Aliya |

| Signature | |

| Website | https://elbasy.kz/en |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Armed Forces of the Republic of Kazakhstan |

| Years of service | 1991–2019 |

| Rank | Supreme Commander |

In 1962, Nazarbayev joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) by prominent member of the Komsomol and a full-time worker for the party. From 1984, Nazarbayev served as the Prime Minister of the Kazakh SSR. During his tenure, he was appointed as the Chairman of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan (QKP) in 1989. In April 1990, Nazarbayev was named as the first president of Kazakhstan by the Supreme Soviet. From there, he supported Russian President Boris Yeltsin against the attempted coup in August 1991 by the Soviet extremists. The Soviet Union fell apart after the coup failed, though Nazarbayev went to great lengths to maintain close economic ties towards Russia by introducing Kazakhstan into the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Nazarbayev ruled a dictatorship in Kazakhstan.[6] He has been accused of human rights abuses by several human rights organisations and suppressed dissent and presided over an authoritarian regime.[7] According to independent observers, from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, no election held in Kazakhstan since independence has been free and fair by international standards.[7][8] In the country's first open direct presidential election, held in 1991, he appeared alone on the ballot with no opposing candidates and won 98% of the vote. An April 1995 referendum extended Nazarbayev's term until 2000 and in August of that year, a constitutional referendum was held which allowed for a new draft for the Constitution of Kazakhstan. In 1999, Nazarbayev was re-elected for 2nd term and again in 2005. In 2010, he announced reforms to encourage a multi-party system. This led to the reinstatement of various parties in Parliament following the 2012 legislative elections, although having little influence and opposition as the parties supported and voted with the government while Nur Otan still had dominant-party control of the Mazhilis. In 2015, Nazarbayev was re-elected with almost 98% of the vote, as he ran virtually unopposed. In January 2017, Nazarbayev proposed constitutional reforms that would delegate powers to the Parliament of Kazakhstan. In May 2018, the Parliament approved a constitutional amendment allowing Nazarbayev to serve as president of the Security Council for life.

In March 2019, he resigned from presidency amid public pressure and was succeeded by Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, a close ally of Nazarbayev, whom overwhelmingly won the following snap presidential elections in June 2019. Nazarbayev still holds the title as "Elbasy" (meaning "Leader of the Nation") where he is immune from any criminal prosecution and currently serves as the chairman of the Security Council, ruling party Nur Otan, and Assembly of People of Kazakhstan. Nazarbayev is also a member of the Constitutional Council, and an honorary member of the Senate of Kazakhstan.

Early life and education

Nazarbayev was born in Chemolgan, a rural town near Almaty, when Kazakhstan was one of the republics of the Soviet Union, to parents Äbish Nazarbayev (1903–1971) and Aljan Nazarbayeva (1910–1977).[9] His father Ábish was a poor labourer who worked for a wealthy local family until Soviet rule confiscated the family's farmland in the 1930s during Joseph Stalin's collectivization policy.[10] Following this, his father took the family to the mountains to live out a nomadic existence.[11] His family's religious tradition was Sunni Islam.

Äbish avoided compulsory military service due to a withered arm he had sustained when putting out a fire.[12] At the end of World War II, the family returned to the village of Chemolgan, and Nazarbayev began to learn the Russian language.[13] He performed well at school and was sent to a boarding school in Kaskelen.[14]

After leaving school, Nazarbayev took up a one-year, government-funded scholarship at the Karaganda Steel Mill in Temirtau.[15] He also spent time training at a steel plant in Dniprodzerzhynsk, and therefore was away from Temirtau when riots broke out there over working conditions.[15] By the age of 20, he was earning a relatively good wage doing "incredibly heavy and dangerous work" in the blast furnace.[16]

Nazarbayev joined the Communist Party in 1962, becoming a prominent member of the Young Communist League (Komsomol)[16] and full-time worker for the party, and attended the Karagandy Polytechnic Institute.[17] He was appointed secretary of the Communist Party Committee of the Karaganda Metallurgical Kombinat in 1972, and four years later became Second Secretary of the Karaganda Regional Party Committee.[17]

In his role as a bureaucrat, Nazarbayev dealt with legal papers, logistical problems, and industrial disputes, as well as meeting workers to solve individual issues.[17] He later wrote that "the central allocation of capital investment and the distribution of funds" meant that infrastructure was poor, workers were demoralised and overworked, and centrally set targets were unrealistic; he saw the steel plant's problems as a microcosm for the problems for the Soviet Union as a whole.[18]

Rise to power

In 1984, Nazarbayev became the Prime Minister of Kazakhstan (Chairman of the Council of Ministers), under Dinmukhamed Kunayev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan.[19] At the sixteenth session of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan in January 1986, Nazarbayev criticized Askar Kunayev, head of the Academy of Sciences, for not reforming his department. Dinmukhamed Kunayev, Nazarbayev's boss and Askar's brother, felt deeply angered and betrayed. Kunayev went to Moscow and demanded Nazarbayev's dismissal while Nazarbayev's supporters campaigned for Kunayev's dismissal and Nazarbayev's promotion.

Kunayev was ousted in 1986 and replaced by a Russian, Gennady Kolbin, who despite his office had little authority in Kazakhstan. Nazarbayev was named party leader on 22 June 1989,[19] only the second Kazakh (after Kunayev) to hold the post. He was Chairman of the Supreme Soviet (head of state) from 22 February to 24 April 1990.

On 24 April 1990, Nazarbayev was elected as the first President of Kazakhstan by the Supreme Soviet. He supported Russian President Boris Yeltsin against the attempted coup in August 1991 by Soviet hardliners.[20] Nazarbayev was close enough to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for Gorbachev to consider him for the post of Vice President of the Soviet Union; however, Nazarbayev turned the offer down. However, on July 29, Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and Nazarbayev discussed and decided that once the New Union Treaty was signed, Nazarbayev would replace Valentin Pavlov as Premier of the Soviet Union.[21]

The Soviet Union disintegrated following the failed coup, though Nazarbayev was highly concerned with maintaining the close economic ties between Kazakhstan and Russia.[22] In the country's first presidential election, held on 1 December, he appeared alone on the ballot and won 95% of the vote.[23] On 21 December, he signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, taking Kazakhstan into the Commonwealth of Independent States.[24]

Presidency

1991–1999: First term

Nazarbayev renamed the former State Defense Committees as the Ministry of Defense and appointed Sagadat Nurmagambetov as Defense Minister on 7 May 1992.

The Supreme Soviet, under the leadership of Chairman Serikbolsyn Abdilin, began debating over a draft constitution in June 1992. Opposition political parties Azat, Jeltoqsan and the Republican Party, held demonstrations in Alma-Ata from 10 to 17 June 1992 calling for the formation of a coalition government, resignation of Sergey Tereshchenko's government and the Supreme Soviet which, at that time, was composed of former Communist Party legislators who had yet to stand in an election.[25] The Constitution, adopted on 28 January 1993, created a strong executive branch with limited checks on executive power.[26] Despite the changes, multiple unexpected dissolutions took place by the end of 1993 starting from local councils in Almaty. On 10 December 1993, the Supreme Council voted to dissolve itself and that same day, a presidential decree was signed which set changes in local representative and executive bodies with elections of the mäslihats (local legislatures) taking place every 5 years and äkims (local heads) being appointed by the president. In March 1994, Kazakhstan held for the first time since independence, held a legislative election which was boycotted by the Azat and Jeltoqsan parties. From there, the pro-presidential People's Union of Kazakhstan Unity party won a majority of 30 seats with independent candidates whom were on presidential-list won 42 seats. The OSCE observers called the elections unfair, reporting an inflated voter turnout.[27]

Throughout the 1990s, privatization and banking reforms took place in Kazakhstan. In June 1994, Nazarbayev amended the Parliament's Economic Memorandum for the next three years, which has been defined as an economic strategy. It included strict measures to reform the economy and establish macroeconomic stability and set the task of carrying out rapid and vigorous privatization. During the introduction of the National Bank of Kazakhstan in December 1993, significant changes were made in which all specialized banks were transformed into a joint stock company, and the National Bank was granted a number of powers. In March 1995, Nazarbayev signed decree setting the National Bank as an independent entity that is accountable only for the head of state.[28]

In 1994, Nazarbayev suggested relocating the capital city from Almaty to Astana, and the official changeover of the capital happened on 10 December 1997.[29]

In March 1995, the Constitutional Court ruled that 1994 legislative elections were held unconstitutionally and as a result, Nazarbayev dissolved the Supreme Council.[30] From that period, all bills were adopted on the basis of presidential decrees such as outlawing any civic participation in an unregistered and/or illegal public association whom would be punished with 15-day jail sentence or fines from 5–10 times the minimum monthly wage in an effort "to fight organized crime."[27] An April 1995 referendum extended Nazarbayev's term, originally set to end in 1996, to until 2000. In August 1995, a referendum was held which allowed for greater presidential powers and established a bicameral Parliament as well. Both the elections for Mazhilis (lower house) and the Senate (upper house) were held in December 1995 which convened in January 1996.[31] Nazarbayev dismissed the accusations from critics of him personally dissolving the legislature by claiming that it was under Constitutional Court's orders, saying "the law is the law, and the President is obliged to abide by the constitution, otherwise, how will we build a rule-of-law state?" and that the cancellation of the 1996 presidential elections was made by the decision of the Assembly of People of Kazakhstan arguing that "Western schemes do not work in our Eurasian expanses."[27]

1999–2006: Second term

On 7 October 1998, a number of amendments were made to the Constitution of Kazakhstan in which the term of office of the president was increased from 5 to 7 years as well as term limits. The changes also removed restriction on the maximum required age of a presidential candidate.[32] The following day on 8 October, Nazarbayev signed decree setting the election date for January 1999. He was re-elected for 2nd term by winning 81% of the vote, defeating his main challenger and former Surpeme Council chairman Serikbolsyn Abdildin.[33]

In February 1999, several pro-presidential parties formed into one party named Otan.[34] At the Founding Congress of the party which was held on 1 March 1999, Nazarbayev was elected as the chairman. From there, he suggested that former PM Sergey Tereshchenko should take over the leading role, noting the constitutional limits on president's affiliation with political parties while Nazarbayev himself remained as de-facto party leader.[35] In July 1999, Nazarbayev signed decree setting the date for the legislative elections.[36] The Otan, for the first time, participated in the elections, winning 23 seats.

In June 2000, the Constitutional Council announced its resolution which declared that Nazarbayev's second term–was in fact–his first due to the adaptation of the new Kazakh Constitution which took place in 1995 during Nazarbayev's first term. This allowed gave him the opportunity to run for another election as his term was set to end in 2007.[37]

Nazarbayev appointed Altynbek Sarsenbayev, who at the time served as the Minister of Culture, Information and Concord, the Secretary of the Security Council, replacing Marat Tazhin, on 4 May 2001. Tazhin became the Chairman of the National Security Committee, replacing Alnur Mussayev. Mussayev became the head of the Presidential Security Service.[38]

2006–2011: Third term

On 4 December 2005, new presidential elections were held where Nazarbayev won by an overwhelming majority of 91.15% (from a total of 6,871,571 eligible participating voters). Nazarbayev was sworn in for another seven-year term on 11 January 2006.[39] In 2009, former UK Cabinet Minister Jonathan Aitken released a biography of the Kazakh leader entitled Nazarbayev and the Making of Kazakhstan. The book takes a generally pro-Nazarbayev stance, asserting in the introduction that he is mostly responsible for the success of modern Kazakhstan.[40]

In 2006, the Otan increased its ranks as all pro-presidential parties began merging into one. Nazarbayev supported the move, stating the need for there to be fewer, but stronger parties that "efficiently defend the interests of the population."[41] In December 2006, the Otan renamed itself into Nur Otan and on 4 July 2007, Nazarbayev was re-elected as the party's chairman.[42][34]

On 18 May 2007, the Parliament of Kazakhstan approved a constitutional amendment which allowed the incumbent president—himself—to run for an unlimited number of five-year terms. This amendment applied specifically and only to Nazarbayev: the original constitution's prescribed maximum of two five-year terms will still apply to all future presidents of Kazakhstan.[43] That same year in August, legislative elections were held from which the Nur Otan won all the contested seats in the Mazhilis, eliminating any form of opposition which sparked controversy and criticism from international organizations and groups within the country.[44] In response, Kazakhstan introduced an amendment by allowing for a two-party system since any party that wins 2nd place in race regardless or not if it passes the 7% electoral threshold is guaranteed to have representation in the Parliament.[45]

Nazarbayev has always emphasized the role of education in the nation's social development. In order to make education affordable, on 13 January 2009, he introduced educational grant "Orken" for the talented youth of Kazakhstan. This decree was amended on 23 September 2016.[46]

2011–2015: Fourth term

In April 2011, Nazarbayev ran for a fourth term, winning 95.5% of the vote with virtually no opposition candidates. Following his victory, he announced the need in finding an "optimal way of empowering parliament, increasing the government's responsibility and improving the electoral process."[47]

On 11 June 2011, Daniel Witt, Vice Chairman of the Eurasia Foundation, acknowledged the role of Nazarbayev and his political reforms:

"[President] Nazarbayev has led Kazakhstan through difficult times and into an era of prosperity and growth. He has demonstrated that he values his U.S. and Western alliances and is committed to achieving democratic governance."[48]

In December 2011, opponents of Nazarbayev rioted in Mangystau, described by the BBC as the biggest opposition movement of his time in power.[49] On 16 December 2011, demonstrations in the oil town of Zhanaozen clashed with police on the country's Independence Day.[50] Fifteen people were shot dead by security forces[51] and almost 100 people were injured. Protests quickly spread to other cities but then died down. The subsequent trial of demonstrators uncovered mass abuse and torture of detainees.[49]

In December 2012, Nazarbayev outlined a forward-looking national strategy called the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy.[52]

In 2014, Nazarbayev suggested that Kazakhstan should change its name to "Kazakh Eli" ("Country of the Kazakhs"), for the country to attract better and more foreign investment, since "Kazakhstan" by its name is associated with other "-stan" countries. Nazarbayev noted Mongolia receives more investment than Kazakhstan because it is not a "-stan" country, even though it is in the same neighborhood, and not as stable as Kazakhstan. However, he noted that decision should be decided by the people on whether the country should change its name.[53][54]

2015–2019: Fifth and final term

In midst of an economic downturn caused by low oil prices and devaluation of the tenge, Nazarbayev for the last time ran again in the 2015 presidential election for the fifth term. From there, he gathered 97.7% of the vote share, making it the largest in Kazakhstan's history.[55] In his victory speech, he empathized the top priority in Nurly Zhol stimulus package that was designed in softening the social blow caused by an economic troubles.[56] The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe criticized the election as falling short of international democratic standards.[57]

In early 2016, it was announced that 1.7 million hectares of agricultural land would be sold at auction. This sparked rare protests around the country which called for Nazarbayev to stop the momentum on land sales and solve the nation's problems as well. In response to the fears of the lands being sold to foreigners especially Chinese, Nazarbayev fired back at claims, calling them "groundless" and warned that any provocateur would be punished.[58] On 1 May 2016, at the Kazakhstan People's Unity Day, Nazarbayev warned that without unity and stability, a crisis similarly in Ukraine would happen.[59] In June 2016, armed attacks in Aktobe took place resulting in deaths of 25 people. Nazarbayev called the incident as terrorist attacks which were orchestrated from abroad to destabilize the country similarly in a colour revolution to which he accused of being infiltrated by the ISIS militants.[60]

On 8 September 2016, Nazarbayev appointed Karim Massimov as the National Security Committee chairman and Bakhytzhan Sagintayev to the post of the PM.[61] Days later on 13 September, Nazarbayev's daughter Dariga was appointed as the member of the Senate. This suggested that Nazarbayev was preparing for his succession to be taken over by Dariga as the cabinet reshuffling had occurred after Uzbek President Islam Karimov's death which created political uncertainty in the neighboring country.[62] Nazarbayev dismissed the claims of hereditary succession in an interview to the Bloomberg News in November 2016, saying that the "transfer of power is spelled out by the Constitution."[63]

In January 2017, Nazarbayev proposed constitutional reforms, which would allow for the Parliament to have greater role in decision making, calling it "a consistent and logical step in the development of the state".[64] The Parliament approved several amendments to the Constitution on 5 March 2017, making the president no longer able to override parliamentary votes of no-confidence, while giving the legislative branch to form a government cabinet, implementing state programs and policies. The move was seen as way by Nazarbayev to ensure the potential of a peaceful transfer of power.[65]

Nazarbayev, along with seventeen heads of state and government from around the world, which included Felipe VI of Spain and leaders of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization member countries, consisting of Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan and India, attended the opening ceremony of Expo 2017 which was held in Astana.[66] An estimated 3.86 million people visited the site with Nazarbayev at the closing ceremony on 10 September 2017 calling it as "Kazakhstan's most brilliant achievements since its independence."[67]

Senate Chair Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, in an interview to BBC News in June 2018, suggested that Nazarbayev's term presidential from 2015 was in fact, the last one as he hinted the possibility that Nazarbayev would not run for re-election which was scheduled for 2020.[68] Minister of Information and Communications Dauren Abaev responded to Tokayev's statements claiming that "there's still a lot of time" for Nazarbayev to decide on whether to run for re-election pointing out that the decision will be primarily based on his. He also added that the country would only benefit if Nazarbayev chooses to run for sixth term.[69]

Resignation

On 19 March 2019, following unusually persistent protests in cities across the country,[70] Nazarbayev announced his resignation as President of Kazakhstan, citing the need for "a new generation of leaders".[4] The announcement was broadcast in a televised address in Astana after which he signed a decree ending his powers from 20 March 2019.[4] Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, speaker of the upper house of parliament, was appointed as president of the country until the end of the presidential term.[4]

His resignation as president notwithstanding, he continues to head the ruling Nur Otan party, remains a member of the Constitutional Council, and keeps his lifetime post as chairman of the Security Council. In his televised address Nazarbayev pointed out that he had been granted the honorary status of elbasy (leader of the nation, leader of the people[note 3]), the title bestowed upon him by parliament in 2010.[70][71]

Various colleagues of Nazarbayev reacted within hours of the announcement, with Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev holding a telephone conversation with Nazarbayev, calling him a "great politician".[72][73] In a cabinet meeting, Russian President Vladimir Putin praised Nazarbayev's leadership, even going as far as to say that the Eurasian Economic Union was Nazarbayev's "brainchild".[74] Other world leaders who sent messages to Nazarbayev included Ilham Aliyev, President of Azerbaijan,[75] Alexander Lukashenko, President of Belarus, and Emomali Rahmon, President of Tajikistan.

Allegations of corruption

.jpg.webp)

Over the course of Nazarbayev's presidency, an increasing number of accusations of corruption and favoritism have been directed against Nazarbayev and his circle. Critics say that the country's government has come to resemble a clan system.[76]

According to The New Yorker, in 1999 Swiss banking officials discovered $85,000,000 in an account apparently belonging to Nazarbayev; the money, intended for the Kazakh treasury, had in part been transferred through accounts linked to James Giffen.[77] Subsequently, Nazarbayev successfully pushed for a parliamentary bill granting him legal immunity, as well as another designed to legalise money laundering, angering critics further.[77] When Kazakh opposition newspaper Respublika reported in 2002 that Nazarbayev had in the mid-1990s secretly stashed away $1,000,000,000 of state oil revenue in Swiss bank accounts, the decapitated carcass of a dog was left outside the newspaper's offices, with a warning reading "There won't be a next time"; the dog's head later turned up outside editor Irina Petrushova's apartment, with a warning reading "There will be no last time."[78][79][80] The newspaper was firebombed as well.[80]

In May 2007, the Parliament of Kazakhstan approved a constitutional amendment which would allow Nazarbayev to seek re-election as many times as he wishes. This amendment applies specifically and only to Nazarbayev, since it states that the first president will have no limits on how many times he can run for office, but subsequent presidents will be restricted to a five-year term.[81]

As of 2015, Kazakhstan has never held an election meeting international standards.[7][8]

In May 2018, the Parliament of Kazakhstan passed a constitutional amendment allowing Nazarbayev to serve as Chairman of the Security Council for life. These reforms, which were approved by the Constitutional Council on 28 June, also expanded the powers of the Security Council, granting it the status of a constitutional body. The amendment states that, "The decisions of the security council and the chairman of the security council are mandatory and are subject to strict execution by state bodies, organisations and officials of the Republic of Kazakhstan."[82]

In December 2020, according to an investigative report by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, it was identified at least $785 million in European and U.S. real estate purchases made by Nazarbaev’s family members and their in-laws in six countries over a 20-year span. This figure includes a handful of properties that have since been sold, including multimillion-dollar apartments in the United States bought by Nazarbaev’s brother, Bolat. It does not include a sprawling Spanish estate owned by Kulibaev, for which a purchase price could not be found. [83]

Eurasian Economic Union

In 1994, Nazarbayev suggested the idea of creating a "Eurasian Union" during a speech at Moscow State University.[84][85][86] On 29 May 2014, Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan signed a treaty to create a Eurasian Economic Union which created a single economic space of 170,000,000 people and came into effect in January 2015. Nazarbayev said shortly after the treaty was signed, "We see this as an open space and a new bridge between the growing economies of Europe and Asia." Nazarbayev named Honorary Chairman of Supreme Eurasian Economic Council in May 2019.[87]

Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy

Nazarbayev unveiled in his 2012 State of the Nation the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy, a long-term strategy to ensure future growth prospects of Kazakhstan, and position Kazakhstan as one of the 30 most developed nations in the world.[88]

Nurly Zhol

President Nazarbayev unveiled in 2014 a multibillion-dollar domestic modernization and reformation plan called Nurly Zhol - The Path to the Future.[89] It was officially approved by the Decree of the President on 6 April 2015. The goal of the plan was for development and improvement of tourist, industrial and housing infrastructure, create 395,500 new jobs, and increase the GDP growth rate 15.7 by 2019.[90] In March 2019, it was announced that the program would be extended to 2025 with its new agenda being focused on developing road infrastructure.[91] According to Minister of Infrastructure and Development Beibut Atamkulov, it is planned that 27,000 kilometres of local roads will be repaired, with 21,000 kilometres of national roads being reconstructed and repaired.[92]

Digital Kazakhstan

President Nazarbayev unveiled this technological modernization initiative to increase Kazakhstan's economic competitiveness through the digital ecosystem development.[93]

Environmental issues

In his 1998 autobiography, Nazarbayev wrote that "The shrinking of the Aral Sea, because of its scope, is one of the most serious ecological disasters being faced by our planet today. It is not an exaggeration to put it on the same level as the destruction of the Amazon rainforest."[94] He called on Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and the wider world to do more to reverse the environmental damage done during the Soviet era.[95]

Stance on nuclear weapons

Kazakhstan inherited from the Soviet Union the world's fourth-largest stockpile of nuclear weapons. Within four years of independence, Kazakhstan possessed zero nuclear weapons.[96] In one of the new government's first major decisions, Nazarbayev closed the Soviet nuclear test site at Semipalatinsk (Semei), where 456 nuclear tests had been conducted by the Soviet military.[97]

During the Soviet era, over 500 military experiments with nuclear weapons were conducted by scientists in the Kazakhstan region, mostly at the Semipalatinsk Test Site, causing radiation sickness and birth defects.[98] As the influence of the Soviet Union waned, Nazarbayev closed the site.[99] He later claimed that he had encouraged Olzhas Suleimenov's anti-nuclear movement in Kazakhstan, and was always fully committed to the group's goals.[100] In what was dubbed "Project Sapphire", the Kazakhstan and United States governments worked closely together to dismantle former Soviet weapons stored in the country, with the Americans agreeing to fund over $800,000,000 in transportation and "compensation" costs.[101]

Nazarbayev encouraged the United Nations General Assembly to establish 29 August as the International Day Against Nuclear Tests. In his article he has proposed a new Non-Proliferation Treaty "that would guarantee clear obligations on the part of signatory governments and define real sanctions for those who fail to observe the terms of the agreement."[102] His foreign minister signed a treaty authorizing the Central Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone on 8 September 2006.[103]

In an oped in The Washington Times, Nazarbayev called for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty to be modernized and better balanced.[104]

In March 2016, Nazarbayev released his "Manifesto: The World. The 21st century."[105] In this manifest the Kazakhstan President called for expanding and replicating existing nuclear-weapon-free zones and stressed the need to modernize existing international disarmament treaties.[106]

Iran

In a speech given in December 2006 marking the fifteenth anniversary of Kazakhstan's independence, Nazarbayev stated he wished to join with Iran in support of a single currency for all Central Asian states and intended to push the idea forward with the President of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, on an upcoming visit. The Kazakh president also reportedly criticised Iran as a terrorism-supporting state. The Kazakh Foreign Ministry released a statement on 19 December, saying the reports were mistaken and contradictory to what the president actually meant.[107]

Religion

Nazarbayev put forward the initiative of holding a forum of world and traditional religions in Astana. Earlier the organisers of similar events were only representatives of leading religions and denominations. Among other similar events aimed at establishing interdenominational dialogue were the meetings of representatives of world religions and denominations held in Assisi, Italy, in October 1986 and January 2002.[108] The first Congress of World and Traditional Religions which gathered in 2003 allowed the leaders of all major religions to develop prospects for mutual cooperation.

Nazarbayev initially espoused anti-religious views during the Soviet era;[109] he later made attempts to support Muslim heritage by performing the Hajj pilgrimage,[109] and supporting mosque renovations.[110]

Under the leadership of Nazarbayev, the Republic of Kazakhstan enacted some degrees of multiculturalism in order to retain and attract talents from diverse ethnic groups among its citizenry, and even from nations that are developing ties of cooperation with the country, in order to coordinate human resources onto the state-guided path of global market economic participation. This principle of the Kazakh leadership has earned it the name "Singapore of the Steppes".[111]

However, in 2012 Nazarbayev proposed reforms, which were later enacted by the parliament, imposing stringent restrictions on religious practices.[112] Religious groups were required to re-register, or face closure.[113] The initiative was explained as an attempt to combat extremism. However, under the new law, many minority religious groups are deemed illegal. In order to exist on a local level, a group must have more than 50 members: more than 500 on a regional level, and more than 5,000 on the national level.[112]

Nazarbayev made critical remarks against the veil, choosing to highlight Turkic traditions over Islam by claiming that "We are Turks, not Arabs" in an open reference to the Turkic heritage while attacking Arab heritage.

Nationalism

In 2014, Vladimir Putin's remarks regarding the historicity of Kazakhstan, in which he stated that Nazarbayev "created a state on a territory that never had a state ... Kazakhs never had any statehood, he has created it"[114][115][116][117][118][119] led to a severe response from Nazarbayev.[120][121][122][123][124][125][126][127][128]

In February 2018, Reuters reported that "Kazakhstan further loosened cultural ties with its former political masters in Moscow ... when a ban on speaking Russian in cabinet meetings took effect ... [Nazarbayev] has also ordered all parliamentary hearings to be held in Kazakh, saying those who are not fluent must be provided with simultaneous translations."[129]

Human rights record

Kazakhstan's human rights situation under Nazarbayev is uniformly described as poor by independent observers. Human Rights Watch says that "Kazakhstan heavily restricts freedom of assembly, speech, and religion. In 2014, authorities closed newspapers, jailed or fined dozens of people after peaceful but unsanctioned protests, and fined or detained worshippers for practicing religion outside state controls. Government critics, including opposition leader Vladimir Kozlov, remained in detention after unfair trials. In mid-2014, Kazakhstan adopted new criminal, criminal executive, criminal procedural, and administrative codes, and a new law on trade unions, which contain articles restricting fundamental freedoms and are incompatible with international standards. Torture remains common in places of detention."[130]

Kazakhstan is ranked 161 out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index, compiled by Reporters Without Borders.[131]

Rule of law

According to a US government report released in 2014, in Kazakhstan:

The law does not require police to inform detainees that they have the right to an attorney, and police did not do so. Human rights observers alleged that law enforcement officials dissuaded detainees from seeing an attorney, gathered evidence through preliminary questioning before a detainee’s attorney arrived, and in some cases used corrupt defense attorneys to gather evidence. [...] The law does not adequately provide for an independent judiciary. The executive branch sharply limited judicial independence. Prosecutors enjoyed a quasi-judicial role and had the authority to suspend court decisions. Corruption was evident at every stage of the judicial process. Although judges were among the most highly paid government employees, lawyers and human rights monitors alleged that judges, prosecutors, and other officials solicited bribes in exchange for favorable rulings in the majority of criminal cases.[132]

Kazakhstan's global rank in the World Justice Project's 2015 Rule of Law Index was 65 out of 102; the country scored well on "Order and Security" (global rank 32/102), and poorly on "Constraints on Government Powers" (global rank 93/102), "Open Government" (85/102) and "Fundamental Rights" (84/102, with a downward trend marking a deterioration in conditions).[133] Kazakhstan's global rank in the World Justice Project's 2020 Rule of Law Index rose and was 62 out 128. Its global rank on "Order and Security" remained high (39/128) and low on "Constraints on Government Powers" (102/128), "Open Government" (81/128) and "Fundamental Rights" (100/128).

The National plan "100 concrete steps" introduced by President Nazarbayev included measures to reform the court system of Kazakhstan, including the introduction of mandatory jury trials for certain categories of crimes (Step 21)[134] and the creation of local police service (Step 30).[135] The implementation of the national plan resulted in Kazakhstan's transition from a five-tier judicial system to a three-tier one in early 2016 yet it severely restricted access to the cassation review of cases by the Supreme Court.[136] However, the expansion of jury trials has not been implemented. Furthermore, President Nazarbayev abolished the local police service in 2018 following the public outrage over the murder of Denis Ten in downtown Almaty.[135]

Foreign policy

During Nazarbayev's presidency the main principle of Kazakhstan's international relations was multi-vector foreign policy, which was based on initiatives to establish friendly relations with foreign partners.[137] Kazakhstan under Nazarbayev became co-founders of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in 2001.[138] U.S. President-elect Donald Trump lauded Nazabayev's leadership and called Kazakhstan's achievements under his presidency a "miracle" during their phone call on 30 November 2016.[139]

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu conducted his first ever visit to Kazakhstan in mid-December 2016, when he met with Nazarbayev. The two countries signed agreements on research and development, aviation, civil service commissions and agricultural cooperation, as well as a declaration on establishing an agricultural consortium.[140]

_31.jpg.webp)

In January 2019, Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa conducted a state visit to Astana to meet with Nazarbayev, in the first visit by an African leader to the country in years. This would be the last foreign head of state that Nazarbayev would receive while in office.[141] Nazarbayev's last state visit to a foreign country took place five days prior to his resignation, visiting the United Arab Emirates to meet Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed.[142]

Post-presidency

According to The Economist, despite his resignation, he is still behind the leadership of the country.[143] His resignation is considered by The Moscow Times to be an attempt to turn him into a Lee Kuan Yew type of public figure.[144] In the month since his resignation, he had met with South Korean President Moon Jae In and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban during their visit to Kazakhstan. Notably, their meetings with Nazarbayev took place separately from their meetings with President Tokayev, who is the de jure head of state. Two days after leaving office, he attended the Nauryz celebrations where he was greeted by the civilian population.[145] In regard to accommodations as the first president, it is known that his personal office (now known as Kokorda) has been moved to a different location in the capital from the presidential palace. It was also reported in late April 2019 that Nazarbayev also maintains a private jet for official and private visits.[146]

He has embarked on two foreign visits since leaving office, to Beijing and Moscow. The former visit took place during the second Belt and Road Forum[147] while the latter took place during the 2019 Moscow Victory Day Parade.[148][149] In late-May, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu announced the naming of Nazarbayev as the honorary President of the Turkic Council.[150] On 7 September, he visited Moscow once again to attend the Moscow City Day celebrations on the VDNKh and to open his pavilion at the trade show.[151] During a visit to the Azerbaijani capital of Baku, he told the hosting President Ilham Aliyev that his father, former President Heydar Aliyev, would be "very delighted" with the development of the capital.[152] In late October, he attended the Enthronement of Japanese emperor Naruhito as the representative of Kazakhstan.[153][154] During this visit, he met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, during which he congratulated him on his election victory and was invited by Zelensky to visit Kyiv.[155][156][157] Nazarbayev met with Spanish tennis player Rafael Nadal during his visit to Kazakhstan for a charity tennis match. During his meeting with Nadal, he personally called former Spanish King Juan Carlos I.[158][159] In October 2019, it was announced that all potential ministerial candidates needed the approval of Nazarbayev before being appointed by Tokayev, with the exception of Minister of Defence, Interior Minister and Foreign Minister.[160]

On 29 November 2019, Nursultan Nazarbayev was named the Honorary Chair of Central Asian Consultative Meeting. It was announced at the second Consultative Meeting of the Heads of State of Central Asia in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.[161]

Capital renaming

On 20 March 2019, after Nazarbayev's resignation, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev proposed renaming the capital Astana to Nur-Sultan (Kazakh: Нұр-Сұлтан/Russian: Нур-Султан)[162] in honor of Nazarbayev. The parliament of Kazakhstan officially voted in favour of the renaming.[163]

COVID-19

Nazarbayev created the Biz Birgemiz ("We are Together" in Kazakh) Fund in March 2020 “to fight the pandemic COVID-19 effectively while supporting the economy.”[164] As of June 2020, the fund gathered over 28 billion tenge (US$69.3 million) to provide financial aid to more than 470,000 families in 23 cities as part of the fund's three waves of assistance.[164] Upon his diagnosis with COVID-19 in mid-June, he received calls and telegrams of support from world leaders, including Vladimir Putin and King Abdullah II of Jordan[165] as well as former President of Croatia Stjepan Mesić.[166]

80th birthday

He recovered from the virus on 3 July,[167] in time to the celebrations of his 80th birthday. It also coincided with the Day of the Capital City. Among the leaders giving congratulations were Armenian President Armen Sarkissian,[168] Russian President Vladimir Putin, former Tatar President Mintimer Shaimiev[169] and former Turkish President Abdullah Gül.[170] Former Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia Grigory Karasin described Nazarbayev an interview honoring his birthday as "the few world politicians who has a vision of political processes".[171] The celebratory events were held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the country.[172] A statue of Nazarbayev in military uniform was unveiled at the National Defense University (an institution that itself which bears his name).[173]

2021 legislative campaign

As Chairman of Nur Otan, Nazarbayev signed a decree in the preparation of the 2021 legislative elections on 4 June 2020 setting the date of closed primaries would be held within the party "for open and political competition, promote civic engagement in the political process, and empower women and the youth of the country" to which he instructed for the party to include 30% of women and 20% of people under the age of 35 in its list.[174] The primaries were held from 17 August to 3 October 2020 where Nazarbayev himself voted online.[175][92]

Personal life

Nazarbayev is married to Sara Alpysqyzy Nazarbayeva. They have three daughters: Dariga, Dinara and Aliya. Aliya's first marriage was notably to Aidar Akayev, the eldest son of former President of Kyrgyzstan Askar Akayev, which for a short period in time, made the two Central Asian leaders related.[176] Having grown up in the USSR, Nazarbayev is fluent in Russian as well as Kazakh and understands English.[177] He has two brothers, Satybaldy (1947–1980) and Bolat (born 1953),[178] as well as one sister named Anip.[179] On 16 August 2020, Nazarbayev's grandson, Aisultan, reportedly died from cardiac arrest in London. Prior to that, Aisultan made several public statements on social media that Nazarbayev was his father and that his life was constantly threatened.[180][181] He also accused his grandfather's associates of plotting and scheming.[182]

On 18 June 2020, it was reported that Nazarbayev had tested positive for COVID-19; a spokesman stated that Nazarbayev would go into isolation and work remotely.[183] On 3 July 2020, Nazarbayev had recovered and was "back on his feet" three weeks after testing positive.[184] Nazarbayev has described his spirituality as being based on the words from Abai Qunanbaiuly, who was a Kazakh poet whose philosophy is based on an enlightened Islam. According to Nazarbayev, Abai's “Words of Wisdom” aided him in attempting to build a modern Kazakhstan after the collapse of the Soviet Union.[185]

Honours

Kazakhstan

Collar of the Order of the Golden Eagle[186]

Collar of the Order of the Golden Eagle[186] Collar of the Order of the First President of Kazakhstan – Leader of the Nation Nursultan Nazarbayev

Collar of the Order of the First President of Kazakhstan – Leader of the Nation Nursultan Nazarbayev Recipient of the Medal "Astana"

Recipient of the Medal "Astana" Recipient of the Medal for "10 Years of the Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

Recipient of the Medal for "10 Years of the Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan" Recipient of the Medal for "10th Anniversary of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

Recipient of the Medal for "10th Anniversary of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Kazakhstan" Recipient of the Medal for "10th Anniversary of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

Recipient of the Medal for "10th Anniversary of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan" Recipient of the Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Railway of Kazakhstan"

Recipient of the Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Railway of Kazakhstan" Recipient of the Medal for "10 Years of the Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

Recipient of the Medal for "10 Years of the Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan" Recipient of the Medal for "50 Years of the Virgin Lands"

Recipient of the Medal for "50 Years of the Virgin Lands" Recipient of the Jubilee Medal "60 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945"

Recipient of the Jubilee Medal "60 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945" Recipient of the Medal for "10 Years of the City of Astana"

Recipient of the Medal for "10 Years of the City of Astana" Recipient of the Medal for "20 Years of the Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

Recipient of the Medal for "20 Years of the Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan" Algys Order[187]

Algys Order[187]

Soviet Union

Recipient of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour

Recipient of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Recipient of the Order of the Badge of Honour

Recipient of the Order of the Badge of Honour Recipient of the Medal "For the Development of Virgin Lands"

Recipient of the Medal "For the Development of Virgin Lands" Recipient of the Jubilee Medal "70 Years of the Armed Forces of the USSR"

Recipient of the Jubilee Medal "70 Years of the Armed Forces of the USSR"

Russian Federation

Russia:

Russia:

Knight of the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-Called[188]

Knight of the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-Called[188] Recipient of the Order of Alexander Nevsky[189]

Recipient of the Order of Alexander Nevsky[189] Recipient of the Medal "In Commemoration of the 1000th Anniversary of Kazan"

Recipient of the Medal "In Commemoration of the 1000th Anniversary of Kazan" Recipient of the Medal "In Commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of Saint Petersburg"

Recipient of the Medal "In Commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of Saint Petersburg" Recipient of the Medal "In Commemoration of the 850th Anniversary of Moscow"

Recipient of the Medal "In Commemoration of the 850th Anniversary of Moscow"

Chechnya:

Chechnya:

.png.webp) Recipient of the Order of Akhmad Kadyrov

Recipient of the Order of Akhmad Kadyrov

Tatarstan:

Tatarstan:

Recipient of the Order "For Merits to the Fatherland"[190]

Recipient of the Order "For Merits to the Fatherland"[190]

Foreign awards

Afghanistan:

Afghanistan:

_-_ribbon_bar.png.webp) Recipient of the Amir Amanullah Khan Award[191]

Recipient of the Amir Amanullah Khan Award[191]

Austria:

Austria:

Grand Star of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria

Grand Star of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria

Azerbaijan:

Azerbaijan:

Belarus:

Belarus:

.svg.png.webp) Belgium:

Belgium:

Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold

Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold

China:

China:

Recipient of the Order of Friendship[195][196]

Recipient of the Order of Friendship[195][196]

Croatia:

Croatia:

Grand Cross of the Grand Order of King Tomislav

Grand Cross of the Grand Order of King Tomislav

Egypt:

Egypt:

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Nile

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Nile

Estonia:

Estonia:

First Class with Collar of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana

First Class with Collar of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana

Finland:

Finland:

Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the White Rose of Finland

Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the White Rose of Finland Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Lion of Finland

Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Lion of Finland

France:

France:

Grand Cross of the Order of Legion of Honour

Grand Cross of the Order of Legion of Honour

Greece:

Greece:

Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer

Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer

Hungary:

Hungary:

_1class_Collar_BAR.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross with Chair of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary

Grand Cross with Chair of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary

Italy:

Italy:

Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

Japan:

Japan:

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum[197]

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum[197]

Kyrgyzstan:

Kyrgyzstan:

Latvia:

Latvia:

Commander Grand Cross with Chain of the Order of the Three Stars[199]

Commander Grand Cross with Chain of the Order of the Three Stars[199]

Lithuania:

Lithuania:

Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great (5 May 2000)[200]

Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great (5 May 2000)[200]

Luxembourg:

Luxembourg:

Grand Cross of the Order of the Oak Crown

Grand Cross of the Order of the Oak Crown

Monaco:

Monaco:

Grand Cross of the Order of Saint-Charles[201]

Grand Cross of the Order of Saint-Charles[201]

Poland:

Poland:

Knight of the Order of the White Eagle

Knight of the Order of the White Eagle

Qatar:

Qatar:

_-_ribbon_bar.gif) Collar of the Order of Independence

Collar of the Order of Independence

Romania:

Romania:

Collar of the Order of the Star of Romania

Collar of the Order of the Star of Romania

Serbia:

Serbia:

Slovakia:

Slovakia:

First Class of the Order of the White Double Cross (2007)[204]

First Class of the Order of the White Double Cross (2007)[204]

South Korea:

South Korea:

_-_ribbon_bar.gif) Recipient of the Grand Order of Mugunghwa

Recipient of the Grand Order of Mugunghwa

Spain:

Spain:

Knight of the Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (2017)[205]

Knight of the Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (2017)[205]

Tajikistan:

Tajikistan:

Recipient of the Order of Ismoili Somoni

Recipient of the Order of Ismoili Somoni

Turkey:

Turkey:

First Class of the Order of the State of Republic of Turkey (22 October 2009)[206]

First Class of the Order of the State of Republic of Turkey (22 October 2009)[206]

Ukraine:

Ukraine:

Member of the Order of Liberty

Member of the Order of Liberty First Class of the Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise

First Class of the Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise

United Arab Emirates:

United Arab Emirates:

Collar of the Order of Zayed

Collar of the Order of Zayed

United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

Uzbekistan:

Uzbekistan:

Recipient of the Gold Medal of Uzbekistan

Recipient of the Gold Medal of Uzbekistan

In popular culture

Nazarbayev is portrayed by Romanian actor Dani Popescu in the 2020 film Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, in which he is depicted as a leader who apparently wants to be part of Donald Trump’s “strongman club” alongside the likes of Vladimir Putin and Kenneth West, recruiting the titular Borat Sagdiyev (Sacha Baron Cohen) to return to the United States to bribe Mikhael Pence with a gift of the country's beloved Jonny the Monkey, who is thereafter eaten by Borat's stowaway daughter Tutar (Maria Bakalova), after which point Nazarbayev faxes Borat to have him present Tutar as a bride to Pence on his suggestion, later to Rudy Giuliani when Borat proves unable to. After Borat and Tutar return to Kazakhstan awaiting execution after failing to fulfill Nazarbayev's wishes, Nazarbayev instead states that "everyone makes mistakes" and offers Borat vodka before leaving, immediately after which point Borat and Tutar discover from looking at the walls of Nazarbayev's that Nazarbayev had masterminded the COVID-19 pandemic by injecting Borat himself with the original strain so that he would serve as an asymptomatic carrier and index case in his travels across the world en route to the Americas. Confronting Nazarbayev, who reveals his motivation for having spread the virus to be routed from how the world treated Kazakhstan after the release of the first film Borat! Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan fourteen years previously, Borat and Tutar record his confession on a smartphone, coercing him into overturning the country's various sexist laws and making it a feminist nation, and replacing the previously abandoned much-beloved "Running of the Jew" festival with the "Running of the Yankee".[208][209]

See also

- Counter-terrorism in Kazakhstan

- Government of Kazakhstan

- List of national leaders

- Politics of Kazakhstan

- Acmetal

Notes

- Kazakhstan declared independence from the Soviet Union on 16 December 1991.

- In Kazakh, his name is spelled Нұрсұлтан Әбішұлы Назарбаев in Cyrillic; Nursultan Ábişuly Nazarbaev in Latin and pronounced [nʊrsʊlˈtɑn æbəɕʊˈlə nɑzɑɾˈbɑjɪf]. In Russian, his name is Нурсултан Абишевич Назарбаев, Nursultan Abishevich Nazarbayev, pronounced [nʊrsʊɫˈtan ɐˈbʲiʂɨvʲɪtɕ nəzɐrˈbajɪf].

- Etymology of elbasy: in Turkic languages, 'el'/'il' means 'the people', 'nation', '(home)land', etc., and 'bas'/'bash' means 'head' (both literally and in the meaning of 'leader'). A similar historical title is Ilkhan.

References

- Specific

- Vakkas Doğantekin (24 May 2019). "Nazarbayev made honorary president of Turkic Council". Anadolu Agency. Ankara. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- Mesquita, Bruce Bueno de (14 January 2013). Principles of International Politics – Bruce Bueno de Mesquita – Google Books. ISBN 9781483304663. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- "Background on Nursultan Nazarbayev". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

The republic's Supreme Soviet elected Nazarbayev president of the Kazakh SSR on April 24, 1990.

- "Veteran Kazakh leader Nazarbayev resigns after three decades in power". Reuters. 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Walker, Shaun (24 April 2015). "Kazakhstan election avoids question of Nazarbayev successor". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- "What happens to Kazakhstan's dictatorship now that its dictator has quit?". The Washington Post. 2019.

- Pannier, Bruce (11 March 2015). "Kazakhstan's long term president to run in show election – again". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

Nazarbayev has clamped down on dissent in Kazakhstan, and the country has never held an election judged to be free or fair by the West.

- Chivers, C.J. (6 December 2005). "Kazakh President Re-elected; voting Flawed, Observers Say". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

Kazakhstan has never held an election that was not rigged.

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 11

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 16

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 20

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 21

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 22

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 23

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 24

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 26

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 27

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 28

- Sally N. Cummings (2002). Power and change in Central Asia. Psychology Press. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-0-415-25585-1. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 73

- "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics - historical state, Eurasia". Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 81

- James Minahan (1998). Miniature empires: a historical dictionary of the newly independent states. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-313-30610-5. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 82

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001). Europe Since 1945 An Encyclopedia. 2. New York City: Garland. p. 715. ISBN 0-8153-4058-3.

- Karen Dawisha; Bruce Parrott (1994). Russia and the new states of Eurasia: the politics of upheaval. Cambridge University Press. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-521-45895-5. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- "KAZAKHSTAN". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Institutional reforms. Economic development". e-history.kz (in Russian). 26 September 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Official site of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan". Akorda. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- "Sociopolitical associations in independent Kazakhstan: Evolution of the phenomenon". Pacific Science Review B: Humanities and Social Sciences. 2 (3): 94–99. 1 November 2016. doi:10.1016/j.psrb.2016.09.018. ISSN 2405-8831.

- MISHRA, MUKESH KUMAR (2009). "Democratisation Process in Kazakhstan: Gauging the Indicators". India Quarterly. 65 (3): 313–327. ISSN 0974-9284.

- "Хронология выборов президента Казахстана". Sputnik Казахстан (in Russian). Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Kazakh 'Rerun:' A Brief History Of Kazakhstan's Presidential Elections". RFE/RL, Inc. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Background on Nur Otan Party". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 5 April 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Report on Kazakstan's Presidential Election: January 10, 1999. Washington D.C. 20 May 1999. p. 15.

- "Указ Президента Республики Казахстан от 7 июля 1999 года № 168 О назначении очередных выборов в Парламент Республики Казахстан". Информационная система ПАРАГРАФ (in Russian). Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Resolution of the Constitutional Council of the Republic of Kazakhstan "About official interpretation of Item 5 of article 42 of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan"". cis-legislation.com. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Robert D'A. Henderson (21 July 2003). Brassey's International Intelligence Yearbook: 2003 Edition. Brassey's. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-57488-550-7. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "January 11. Kazinform's timeline of major events". lenta.inform.kz (in Russian). Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Aitken, Jonathan (2009). Nazarbayev and the Making of Kazakhstan. London: Continuum. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-1-4411-5381-4.

- "Pro-Nazarbaev Party Merges With President's Power Base". RFE/RL. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Pannier, Bruce (22 December 2006). "Kazakhstan: Ruling Party Gets Even Bigger". RFE/RL. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Holley, David (19 May 2007). "Kazakhstan lifts term limits on long-ruling leader". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- "Ruling Party Sweeps Kazakh Parliamentary Polls | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. 19 August 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Dave, Bhavna (2011). Nations in Transit 2011 (PDF). pp. 269–270.

- "Kazakh President amends decree on educational grant for talented youngsters". Kazinform. 23 September 2016. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- "Kazakhstan President Nazarbayev sworn in for new term". BBC News. 8 April 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Witt, Daniel (11 June 2011). "Kazakhstan's Presidential Election Shows Progress". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "Abuse claims swamp Kazakh oil riot trial". BBC. 15 May 2012. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- "Kazakhstan: Zhanaozen Oil Workers Did Not Take Up Arms". KazWorld.info. 15 December 2016. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "The Stable State Of Nursultan Nazarbayev's Kazakhstanl". Forbes. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Keene, Eli (21 February 2013). "Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy Leads to Government Restructuring". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "WorldViews". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "Kazakhstan: President suggests renaming the country". BBC. 7 February 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- Lillis, Joanna (27 April 2015). "Kazakhstan: Nazarbayev Apologetic for Lopsided Election Results | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- INFORM.KZ (27 April 2015). "Казахстан сохранит ключевые приоритеты во внутренней и внешней политике - Н.Назарбаев". www.inform.kz (in Russian). Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights – Elections. Archived 9 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kazakhstan's land reform protests explained". BBC News. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Staff, Reuters (1 May 2016). "Kazakh leader evokes Ukraine as land protests spread". Reuters. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Orazgaliyeva, Malika (9 June 2016). "Kazakh President Declares June 9 as National Day of Mourning". The Astana Times. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Bakytzhan Sagintayev is appointed Kazakhstan's new prime minister". TASS. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Staff, Reuters (13 September 2016). "Kazakh leader promotes daughter, confidant in reshuffle". Reuters. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Kazakh President Nazarbayev Says Power Won't Be Family Business". Bloomberg.com. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Uatkhanov, Yerbolat (25 January 2017). "Kazakh President, Special Panel Mull Major Political Reforms". The Astana Times. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Staff, Reuters (6 March 2017). "Kazakhstan parliament passes reforms reducing presidential powers". Reuters. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Kazakhstan celebrates inauguration of Expo 2017 Astana". www.efe.com. 10 June 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Expo Astana 2017 closes after three successful months". www.efe.com. 10 September 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "'I doubt Kazakh president will run again'". BBC News. 20 June 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Айтжанова, Ботагоз (21 June 2018). ""Решение за Президентом" - Абаев об участии Назарбаева в выборах в 2020 году". Tengrinews.kz (in Russian). Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Kazakh President Nazarbaev Abruptly Resigns, But Will Retain Key Roles". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Обращение Главы государства Нурсултана Назарбаева к народу Казахстана Archived 19 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The official web site of the President of Kazakhstan, 19 March 2019.

- "Shavkat Mirziyoyev Talks with the First President of Kazakhstan on the Phone". president.uz. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "Shavkat Mirziyoyev: Nursultan Nazarbayev is a great politician". Inform.

- Ruptly (20 March 2019). "Russia: Putin praises former Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev" – via YouTube.

- "Official web-site of President of Azerbaijan Republic". en.president.az. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Martha Brill Olcott (1 September 2010). Kazakhstan: Unfulfilled Promise. Carnegie Endowment. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-87003-299-8. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016.

- Seymour M. Hersh (9 July 2001). "The Price of oil". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Peter Baker (11 June 2002). "As Kazakh scandal unfolds, Soviet-style reprisals begin". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Casey Michel (7 August 2015). "Kazakhstan Goes After Opposition Media in New York Federal Court". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Danny O'Brien (4 August 2015). "How Kazakhstan is Trying to Use the US Courts to Censor the Net". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Holley, David (19 May 2007). "Kazakhstan lifts term limits on long-ruling leader". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Aigerim Seisembayeva (13 July 2018). "Kazakh President given right to head National Security Council for life". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Big Houses, Deep Pockets: The Nazarbaev Family's Opulent Offshore Real Estate Empire". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Holding-Together Regionalism: Twenty Years of Post-Soviet Integration. Libman A. and Vinokurov E. (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2012, p. 220.)

- "Президент Республики Казахстан Н. А. Назарбаев о евразийской интеграции. Из выступления в Московском государственном университете им. М. В. Ломоносова 29 марта 1994 г." Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- Alexandrov, Mikhail. Uneasy Alliance: Relations Between Russia and Kazakhstan in the Post-Soviet Era, 1992-1997. Greenwood Press, 1999, p. 229. ISBN 978-0-313-30965-6

- "Nazarbayev named "Honorary Chairman" of Supreme Eurasian Economic Council". Kazinform. 29 May 2019. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Strategy 2050: Kazakhstan's Road Map to Global Success". EdgeKZ. Archived from the original on 13 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- "Kazakhstan's Nurly Zhol and China's Economic Belt of the Silk Road: Confluence of Goals". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "Nurly Zhol Infrastructure Development Program for 2015-2019". primeminister.kz. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- "State Program Nurly Zhol to Be Extended until 2025". Kazakh-tv.kz. 13 March 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- Satubaldina, Assel (8 October 2020). "Over 10,000 Candidates Participate in Nur Otan Party Primaries, as Party Concludes First Stage". The Astana Times. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- "Digital Kazakhstan initiative presented at Web Summit 2017". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 42

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 41

- "NTI Kazakhstan Profile". Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI). Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- "Kazakhstan and US Renew Nonproliferation Partnership". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 141

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 143

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 142

- Nazarbayev 1998, p. 150

- Right time for building global nuclear security. Chicago Tribune (11 April 2010). Retrieved 3 February 2011. Archived 10 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Central Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free-Zone (CANWFZ)". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- oped Archived 27 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Times

- "Manifesto: The World. The 21st century". Akorda. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Manifest by Kazakh President Calls for Global Nuclear Disarmament, Steps to End Global Conflicts". Astana Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Kazakhstan dismisses alleged anti-Iran comments from president". Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2007.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Congress of World Religions – About Congress of leaders of world and traditional religions Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Religions-congress.org (15 October 2007). Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Ideology and National Identity in Post-Communist Foreign Policies By Rick Fawn, p. 147

- Moscow's Largest Mosque to Undergo Extension Archived 4 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Preston, Peter (19 July 2009). "How Nursultan became the most loved man on Earth". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Leonard, Peter (29 September 2011). "Kazakhstan: Restrictive Religion Law Blow To Minority Groups". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- "Kazakhstan: Religion Law Restricting Faith in the Name of Tackling Extremism?". EurasiaNet. 12 November 2012. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- Diplomat, Casey Michel, The. "Putin's Chilling Kazakhstan Comments". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Traynor, Ian (1 September 2014). "Kazakhstan is latest Russian neighbour to feel Putin's chilly nationalist rhetoric". Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "Kazakhs Worried After Putin Questions History of Country's Independence". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Vladimir Putin Continues Soviet Rhetoric by Questioning Kazakhstan's 'Created' Independence". 1 September 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Trilling, David (30 August 2014). "As Kazakhstan's Leader Asserts Independence, Did Putin Just Say, 'Not So Fast'?". EurasiaNet. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Brletich, Samantha. "The Crimea Model: Will Russia Annex the Northern Region of Kazakhstan?". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Russian and Kazakh Leaders Exchange Worrying Statements". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Nazarbayev's Severe Response to Putin". Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Nazarbayev vs Putin". 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2016 – via YouTube.

- Lillis, Joanna (27 January 2016). "Kazakhstan creates its own Game of Thrones to defy Putin and Borat". Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "New Kazakh TV series a riposte to Putin and Borat". Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Lillis, Joanna (6 January 2015). "Kazakhstan Celebrates Statehood in Riposte to Russia". EurasiaNet. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Kazakhstan MP responds to Vladimir Putin's statement on lack of statehood in Kazakhstan - Politics - Tengrinews". Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Najibullah, Farangis (3 September 2014). "Putin Downplays Kazakh Independence, Sparks Angry Reaction". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016 – via Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty.

- Michel, Casey (19 January 2015). "Even Vladimir Putin's Authoritarian Allies Are Fed Up With Russia's Crumbling Economy". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Lost in translation? Kazakh leader bans cabinet from speaking Russian Archived 25 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. 27 February 2018.

- Human Rights Watch, World Report 2015: Kazakhstan Archived 28 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 2015.

- "World Press Freedom Index 2014". Reporters Without Borders. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2013: Kazakhstan", released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. Retrieved November 1, 2015

- "Rule of Law Index 2015". World Justice Project. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Trochev, Alexei; Slade, Gavin (2019), Caron, Jean-François (ed.), "Trials and Tribulations: Kazakhstan's Criminal Justice Reforms", Kazakhstan and the Soviet Legacy: Between Continuity and Rupture, Singapore: Springer, pp. 75–99, doi:10.1007/978-981-13-6693-2_5, ISBN 978-981-13-6693-2, retrieved 4 December 2020

- Slade, Gavin; Trochev, Alexei; Talgatova, Malika (2 December 2020). "The Limits of Authoritarian Modernisation: Zero Tolerance Policing in Kazakhstan". Europe-Asia Studies. 0 (0): 1–22. doi:10.1080/09668136.2020.1844867. ISSN 0966-8136.

- "Kazakh President instructs to improve court system". kazinform. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Nazarbayev's trust-based relations with foreign partners help promote Kazakhstan's interests". inform.kz. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Gill (30 November 2001). "Shanghai Five: An Attempt to Counter U.S. Influence in Asia?". Brookings.

- "Kazakhstan: Trump talked up leader's 'miracle' in call". The Hill. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- "PM Netanyahu meets with Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev". mfa.gov.il. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- "Mnangagwa arrives in Kazakhstan". The Zimbabwe Mail. 19 January 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- "Mohammad Bin Zayed receives President of Kazakhstan". gulfnews.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "The people of Kazakhstan wonder who their next president will be". The Economist. 11 April 2019. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Hess, Max (22 March 2019). "Nazarbayev's Resignation Is an Attempt to Institutionalize His System". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Nauryz celebrated throughout the country". The Astana Times. 26 March 2019. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.