Kazakhs

The Kazakhs (also spelled Kazaks, Qazaqs; Kazakh: singular: Қазақ, Qazaq, [qɑˈzɑq] (![]() listen), plural: Қазақтар, Qazaqtar, [qɑzɑqˈtɑr] (

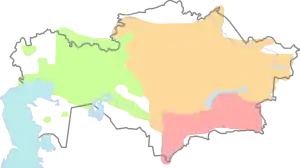

listen), plural: Қазақтар, Qazaqtar, [qɑzɑqˈtɑr] (![]() listen); the English name is transliterated from Russian; Russian: Казахи) are a Turkic ethnic group who mainly inhabit the Ural Mountains and northern parts of Central and East Asia (largely Kazakhstan, but also parts of Russia, Uzbekistan, Mongolia and China) in Eurasia. Kazakh identity is of medieval origin and was strongly shaped by the foundation of the Kazakh Khanate between 1456 and 1465, when several tribes under the rule of the sultans Zhanibek and Kerey departed from the Khanate of Abu'l-Khayr Khan.

listen); the English name is transliterated from Russian; Russian: Казахи) are a Turkic ethnic group who mainly inhabit the Ural Mountains and northern parts of Central and East Asia (largely Kazakhstan, but also parts of Russia, Uzbekistan, Mongolia and China) in Eurasia. Kazakh identity is of medieval origin and was strongly shaped by the foundation of the Kazakh Khanate between 1456 and 1465, when several tribes under the rule of the sultans Zhanibek and Kerey departed from the Khanate of Abu'l-Khayr Khan.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 18 690 200[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,800,000[3] | |

| 800,000[4] | |

| 647,732[5] | |

| 102,526[6] | |

| 33,200[7] | |

| 24,636[8] | |

| 10,000[9] | |

| 9,600[10] | |

| 3,000–15,000[11][12] | |

| 5,639[13] | |

| 5,526[14] | |

| 5,000[15] | |

| 1,685[16] | |

| 1,355[17] | |

| 1,000[18] | |

| Languages | |

| Kazakh Russian (in Russia and Kazakhstan) and Chinese (in China) (widely spoken as an L2)[19][20] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam[21][5][22][23][24] Minorities: Christianity,[25] Atheism[26] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Turkic peoples and Mongols | |

The Kazakhs are descendants of several ancient Turkic tribes – Argyns, Dughlats, Naimans, Jalairs, Keraits, Qarluqs and of the Kipchaks.[27]

In Russian the term Kazakh is used to refer to ethnic Kazakhs, while the term "Kazakhstanis" usually refers to all inhabitants or citizens of Kazakhstan regardless of ethnicity. In English no clear differences are made.

Etymology of Kazakh

The Kazakhs likely began using that name during the 15th century.[28] There are many theories on the origin of the word Kazakh or Qazaq. Some speculate that it comes from the Turkish verb qaz ("wanderer, warrior, free, independent") or that it derives from the Proto-Turkic word khasaq (a wheeled cart used by the Kazakhs to transport their yurts and belongings).[29]

Another theory on the origin of the word Kazakh (originally Qazaq) is that it comes from the ancient Turkic word qazğaq, first mentioned on the 8th century Turkic monument of Uyuk-Turan.[30] According to Turkic linguist Vasily Radlov and Orientalist Veniamin Yudin, the noun qazğaq derives from the same root as the verb qazğan ("to obtain", "to gain"). Therefore, qazğaq defines a type of person who seeks profit and gain.[31]

Kazakh

Kazakh was a common term throughout medieval Central Asia, generally with regard to individuals or groups who had taken or achieved independence from a figure of authority. Timur described his own youth without direct authority as his Qazaqliq ("Qazaq-ness").[32] At the time of the Uzbek nomads Conquest of Central Asia, the Uzbek Abu'l-Khayr Khan had differences with the Chinggisid chiefs Giray/Kirey and Janibeg/Janibek, descendants of Urus Khan.

These differences probably resulted from the crushing defeat of Abu'l-Khayr Khan at the hands of the Qalmaqs.[33] Kirey and Janibek moved with a large following of nomads to the region of Zhetysu on the border of Moghulistan and set up new pastures there with the blessing of the Moghul Chingisid Esen Buqa, who hoped for a buffer zone of protection against the expansion of the Oirats.[34] That is not explicitly explained to be the reason for later Kazakhs' taking the name permanently, but it is the only historically verifiable source of the ethnonym. The group under Kirey and Janibek are called in various sources Qazaqs and Uzbek-Qazaqs (those independent of the Uzbek khans). The Russians originally called the Kazakhs 'Kirgiz' and later Kirghiz-Kaisak to distinguish them from the Kyrgyz proper.

In the 17th century, Russian convention seeking to distinguish the Qazaqs of the steppes from the Cossacks of the Imperial Russian Army suggested spelling the final consonant with "kh" instead of "q" or "k", which was officially adopted by the USSR in 1936.[35]

- Kazakh – Казах

- Cossack – Казак

The Ukrainian term Cossack probably comes from the same Kypchak etymological root: wanderer, brigand, independent free-booter.[36][37]

Oral history

Their nomadic pastoral lifestyle made Kazakhs keep an epic tradition of oral history. The nation, which amalgamated nomadic tribes of various Kazakh origins, managed to preserve the distant memory of the original founding clans. It was important for Kazakhs to know their genealogical tree for no less than seven generations back (known as şejire, from the Arabic word shajara – "tree").

Three Kazakh Zhuz (Hordes)

In modern Kazakhstan, tribalism is fading away in business and government life. Still it is common for Kazakhs to ask each other the tribe they belong to when they become acquainted with one another. Now, it is more of a tradition than necessity, and there is no hostility between tribes. Kazakhs, regardless of their tribal origin, consider themselves one nation.

Those modern-day Kazakhs who yet remember their tribes know that their tribes belong to one of the three Zhuz (juz, roughly translatable as "horde" or "hundred"):

- The Senior Horde (also called Elder or Great) (Uly juz)

- The Middle (also called Central) (Orta juz)

- The Junior (also called Younger or Lesser) (Kishi juz)

History of the Hordes

There is much debate surrounding the origins of the Hordes. Their age is unknown so far in extant historical texts, with the earliest mentions in the 17th century. The Turkologist Velyaminov-Zernov believed that it was the capture of the important cities of Tashkent, Yasi, and Sayram in 1598 by Tevvekel (Tauekel/Tavakkul) Khan that separated the Qazaqs, as they possessed the cities for only part of the 17th century.[38] The theory suggests that the Qazaqs then divided among a wider territory after expanding from Zhetysu into most of the Dasht-i Qipchaq, with a focus on the trade available through the cities of the middle Syr Darya, to which Sayram and Yasi belonged. The Junior juz originated from the Nogais of the Nogai Horde.

Language

The Kazakh language is a member of the Turkic language family, as are Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Uyghur, Turkmen, modern Turkish, Azeri and many other living and historical languages spoken in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Xinjiang, and Siberia.

Kazakh belongs to the Kipchak (Northwestern) group of the Turkic language family. Kazakh is characterized, in distinction to other Turkic languages, by the presence of /s/ in place of reconstructed proto-Turkic */ʃ/ and /ʃ/ in place of */tʃ/; furthermore, Kazakh has /ʒ/ where other Turkic languages have /j/.

Kazakh, like most of the Turkic language family lacks phonemic vowel length, and as such there is no distinction between long and short vowels.

Kazakh was written with the Arabic script during the 19th century, when a number of poets, educated in Islamic schools, incited a revolt against Russia. Russia's response was to set up secular schools and devise a way of writing Kazakh with the Cyrillic alphabet, which was not widely accepted. By 1917, the Arabic script was reintroduced, even in schools and local government.

In 1927, a Kazakh nationalist movement sprang up but was soon suppressed. At the same time the Arabic script was banned and the Latin alphabet was imposed for writing Kazakh. The native Latin alphabet was in turn replaced by the Cyrillic alphabet in 1940 by soviet interventionists. Today, there are efforts to return to the Latin script.

Kazakh is a state (official) language in Kazakhstan. It is also spoken in the Ili region of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China, where the Arabic script is used, and in western parts of Mongolia (Bayan-Ölgii and Khovd province), where Cyrillic script is in use. European Kazakhs use the Latin alphabet.

Religion

Almost all ethnic Kazakhs today are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school. Their ancestors, however, believed in Shamanism and Tengrism, then Zoroastrianism, Buddhism and Christianity including Church of the East. Islam was first introduced to ancestors of modern Kazakhs during the 8th century when the Arab missionaries entered Central Asia. Islam initially took hold in the southern portions of Turkestan and thereafter gradually spread northward.[39] Islam also took root because of the missionary work of Samanid rulers, notably in areas surrounding Taraz[40] where a significant number of Turks accepted Islam. Over time, most ethnic Kazakhs became devout Muslims, with many performing the Hajj to Mecca and others choosing to perform the pilgrimage in the closer city of Turkistan, which was considered to be the “Mecca of the East”. Additionally, in the late 14th century, the Golden Horde propagated Islam among Kazakhs and other tribes. Islam in Kazakhstan peaked during the era of the Kazakh Khanate, especially under rulers such as Ablai Khan and Kasym Khan. During the 18th century, Russian influence toward the region rapidly increased throughout Central Asia. Led by Catherine, the Russians initially demonstrated a willingness in allowing Islam to flourish as Muslim clerics were invited into the region to preach to the Kazakhs, whom the Russians viewed as "savages" and "ignorant" of morals and ethics.[41][42] However, Russian policy gradually changed toward weakening Islam by introducing pre-Islamic elements of collective consciousness.[43] Such attempts included methods of eulogizing pre-Islamic historical figures and imposing a sense of inferiority by sending Kazakhs to highly elite Russian military institutions.[43] In response, Kazakh religious leaders attempted to bring in pan-Turkism, though many were persecuted as a result.[44] During the Soviet era, Muslim institutions survived only in areas that Kazakhs significantly outnumbered non-Muslims, such as non-indigenous Russians, by everyday Muslim practices.[45] In an attempt to conform Kazakhs into Communist ideologies, gender relations and other aspects of Kazakh culture were key targets of social change.[42]

In more recent times, however, Kazakhs have gradually employed a determined effort in revitalizing Islamic religious institutions after the fall of the Soviet Union. Most Kazakhs continue to identify with their Islamic faith,[46] and even more devotedly in the countryside. Those who claim descent from the original Muslim soldiers and missionaries of the 8th-century command substantial respect in their communities.[47] Kazakh political figures have also stressed the need to sponsor Islamic awareness. For example, the Kazakh Foreign Affairs Minister, Marat Tazhin, recently emphasized that Kazakhstan attaches importance to the use of "positive potential Islam, learning of its history, culture and heritage."[48]

Pre-Islamic beliefs, such as worship of the sky, the ancestors, and fire, continued to a great extent to be preserved among the common people, however. Kazakhs believed in the supernatural forces of good and evil spirits, of wood goblins and giants. To protect themselves from them and from the evil eye, Kazakhs wore protection beads and talismans. Shamanic beliefs are still widely preserved among Kazakhs, as well as the belief in the strength of the bearers of that worship, the shamans, which Kazakhs call bakhsy. Unlike the Siberian shamans, who used drums during their rituals, Kazakh shamans, who could also be men or women, played (with a bow) on a stringed instrument similar to a large violin. At present both Islamic and pre-Islamic beliefs continue to be found among Kazakhs, especially among the elderly.[23] According to 2009 national census 39,172 Kazakhs are Christians.[25]

Origin and ethnogenesis

Recent linguistic, genetic and archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest Turkic peoples descended from agricultural communities in Northeast China who moved westwards into Mongolia in the late 3rd millennium BC, where they adopted a pastoral lifestyle.[49][50][51][52][53] By the early 1st millennium BC, these peoples had become equestrian nomads.[49] In subsequent centuries, the steppe populations of Central Asia appear to have been progressively replaced and Turkified by East Asian nomadic Turks, moving out of Mongolia.[54][55]

Genetic studies

According to mitochondrial DNA studies[56] (where sample consisted of only 246 individuals), the main maternal lineages of Kazakhs are: D (17.9%), C (16%), G (16%), A (3.25%), F (2.44%) of Eastern Eurasian origin (58%), and haplogroups H (14.1), T (5.5), J (3.6%), K (2.6%), U5 (3%), and others (12.2%) of western Eurasian origin (41%). An analysis of ancient Kazakhs found that East Asian haplogroups such as A and C did not begin to move into the Kazakh steppe region until around the time of the Xiongnu (1st millennia BCE), which is around the onset of the Sargat Culture as well (Lalueza-Fox 2004).[57]

Gokcumen et al. (2008) tested the mtDNA of a total of 237 Kazakhs from Altai Republic and found that they belonged to the following haplogroups: D(xD5) (15.6%), C (10.5%), F1 (6.8%), B4 (5.1%), G2a (4.6%), A (4.2%), B5 (4.2%), M(xC, Z, M8a, D, G, M7, M9a, M13) (3.0%), D5 (2.1%), G2(xG2a) (2.1%), G4 (1.7%), N9a (1.7%), G(xG2, G4) (0.8%), M7 (0.8%), M13 (0.8%), Y1 (0.8%), Z (0.4%), M8a (0.4%), M9a (0.4%), and F2 (0.4%) for a total of 66.7% mtDNA of Eastern Eurasian origin or affinity and H (10.5%), U(xU1, U3, U4, U5) (3.4%), J (3.0%), N1a (3.0%), R(xB4, B5, F1, F2, T, J, U, HV) (3.0%), I (2.1%), U5 (2.1%), T (1.7%), U4 (1.3%), U1 (0.8%), K (0.8%), N1b (0.4%), W (0.4%), U3 (0.4%), and HV (0.4%) for a total of 33.3% mtDNA of Western Eurasian origin or affinity.[58] Comparing their samples of Kazakhs from Altai Republic with samples of Kazakhs from Kazakhstan and Kazakhs from Xinjiang, the authors have noted that "haplogroups A, B, C, D, F1, G2a, H, and M were present in all of them, suggesting that these lineages represent the common maternal gene pool from which these different Kazakh populations emerged."[58] In every sample of Kazakhs, D (predominantly northern East Asian, such as Japanese, Okinawan, Korean, Manchu, Mongol, Han Chinese, Tibetan, etc., but also having several branches among indigenous peoples of the Americas) is the most frequently observed haplogroup (with nearly all of those Kazakhs belonging to the D4 subclade), and the second-most frequent haplogroup is either H (predominantly European) or C (predominantly indigenous Siberian, though some branches are present in the Americas, East Asia, and eastern and northern Europe).

In a sample of 54 Kazakhs and 119 Altaian Kazakh, the main paternal lineages of Kazakhs are: C (66.7% and 59.5%), O (9% and 26%), N (2% and 0%), J (4% and 0%), R (9% and 1%).[59]

In a sample of 3 ethnic Kazakhs the main paternal lineages of Kazakhs are C, R, G, J, N, O, Q.[60]

According to a large-scale Kazakhstani study (1294 persons) published in 2017, Kazakh males belong to the following Y-DNA haplogroups :

| Haplogroup | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| C2-M217 | 50.85%, including 24.88% C-M401, 17.39% C-M86, 6.18% C-M407, and 2.40% C-M217(xM401, M48, M407) | C-M407 was found predominantly among members of the Qongyrat tribe (64/95 = 67.37%) C-M86 was found predominantly among members of the Lesser/Junior Jüz (30/86 = 34.9% Jetyru) and the Alshyns in particular (58/76 = 76.3% Baiuly, 80/122 = 65.6% Alimuly) |

| R-M207 | 12.13%, including 6.03% R1a-M198, 3.17% R1b-M478, 1.62% R1b-M269, 1.00% R2-M124 (predicted), and 0.31% R-M207(xM198, M478, M269, M124) | R1b-M478 was found predominantly among members of the Qypshaq tribe (12/29 = 41.38%)

R1a-M198 was found with notable frequency among members of the Suan (13/41 = 31.71%) and Oshaqty (8/29 = 27.59%) tribes and among members of the Qoja caste of Islamic scholars and gentlemen (6/30 = 20.00%), although C-M401 was more common than R1a-M198 among members of the Suan and Oshaqty tribes (25/41 = 60.98% and 11/29 = 37.93%, respectively) |

| O-M175 | 10.82%, including 9.43% O-M134, 0.70% O-M122(xM134), and 0.70% O-M175(xM122) | O-M134 was found predominantly among members of the Naiman tribe (102/155 = 65.81%), |

| J-M304 | 8.19%, including 4.10% J2a-M410 (predicted), 3.86% J1-M267 (predicted), and 0.23% J-M304(xJ1, J2a) | J1-M267 (predicted) was found predominantly among members of the Ysty tribe (36/57 = 63.16%) |

| N-M231 | 5.33%, including 3.79% N-M46, 1.24% N-P43, and 0.31% N-M231(xP43, M46) | N-M46 was found predominantly among members of the Syrgeli tribe (21/32 = 65.63%) |

| G-M201 | 4.95%, including 3.40% G1-M285, 1.39% G2-P287, and 0.15% G-M201(xM285, P287) | G1-M285 was found predominantly among members of the Argyn tribe (26/50 = 52.00%) |

| Q-M242 | 3.17% | Q-M242 was found predominantly among members of the Qangly tribe (27/40 = 67.50%) |

| E-M35 | 1.78% | More than half (13/23 = 56.5%) of the Kazakh E-M35 individuals observed in the study have been observed in the sample of the Jetyru tribe (13/86 = 15.1% E-M35) |

| I-M170 | 1.55%, including 0.85% I2a-L460 (predicted), 0.39% I1-M253 (predicted), and 0.31% I2b-L415 (predicted) | |

| D-M174 | 0.46% | |

| L-M20 | 0.31% (predicted) | |

| H | 0.23% (predicted) | |

| T | 0.15% (predicted) | |

| K* | 0.08% | |

| Source[61] | ||

The distribution was inhomogeneous for some Y-DNA haplogroups: because of that lack of homogeneity among Kazakhs in regard to Y-chromosome DNA, the real percentage of present-day Kazakhs who belong to each Y-DNA haplogroup may differ from the percentages found in the study, depending on the proportion of each tribe in the total population of Kazakhs.

Population

| 1897 | 1917 | 1926 | 1939 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 | 1999 | 2009 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81.7% | 58.0% | 58.5% | 37.8% | 29.8% | 36.2% | 37.8% | 53.5% | 63.1% | 67.5% |

Historical population of Kazakhs: Huge drop in population of Ethnic Kazakhs between 1897 and 1959 years caused by colonial politics of Russian Empire, then genocide which occurred during Stalin Regime. Sarah Cameron (Associate Professor of University of Maryland) described this genocide on her book, "The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan".

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1897 | 10,370,500 |

| 1917 | 9,867,397 |

| 1926 | 3,627,612 |

| 1939 | 2,327,625 |

| 1959 | 2,794,966 |

| 1979 | 5,289,349 |

| 1989 | 6,227,549 |

| 1999 | 8,011,452 |

| 2009 | 10,096,763 |

| 2018 | 16,212,645 |

Kazakh minorities

Russia

.png.webp)

In Russia, the Kazakh population lives primarily in the regions bordering Kazakhstan. According to latest census (2002) there are 654,000 Kazakhs in Russia, most of whom are in the Astrakhan, Volgograd, Saratov, Samara, Orenburg, Chelyabinsk, Kurgan, Tyumen, Omsk, Novosibirsk, Altai Krai and Altai Republic regions. Though ethnically Kazakh, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, those people acquired Russian citizenship.

| 1939 | % | 1959 | % | 1970 | % | 1979 | % | 1989 | % | 2002 | % | 2010 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 356 646 | 0.33 | 382 431 | 0.33 | 477 820 | 0.37 | 518 060 | 0.38 | 635 865 | 0.43 | 653 962 | 0.45 | 647 732 | 0.45 |

China

Kazakhs migrated into Dzungaria in the 18th century after the Dzungar genocide resulted in the native Buddhist Dzungar Oirat population being massacred.

Kazakhs, called "哈萨克族" in Chinese (pinyin: Hāsàkè Zú; lit. '"Kazakh people" or "Kazakh tribe"') are among 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China. Thousands of Kazakhs fled to China during the 1932–1933 famine in Kazakhstan.

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 30,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, Hui led by General Ma Bufang massacred their fellow Muslim Kazakhs, until there were 135 of them left.[63][64][65]

From Northern Xinjiang over 7,000 Kazakhs fled to the Tibetan-Qinghai plateau region via Gansu and were wreaking massive havoc so Ma Bufang solved the problem by relegating Kazakhs to designated pastureland in Qinghai, but Hui, Tibetans, and Kazakhs in the region continued to clash against each other.[66] Tibetans attacked and fought against the Kazakhs as they entered Tibet via Gansu and Qinghai. In northern Tibet, Kazakhs clashed with Tibetan soldiers, and the Kazakhs were sent to Ladakh.[67] Tibetan troops robbed and killed Kazakhs 400 miles east of Lhasa at Chamdo when the Kazakhs were entering Tibet.[68][69]

In 1934, 1935, and from 1936–1938 Qumil Eliqsan led approximately 18,000 Kerey Kazakhs to migrate to Gansu, entering Gansu and Qinghai.[70]

In China there is one Kazakh autonomous prefecture, the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and three Kazakh autonomous counties: Aksai Kazakh Autonomous County in Gansu, Barkol Kazakh Autonomous County and Mori Kazakh Autonomous County in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Many Kazakhs in China are not fluent in Standard Chinese, instead speaking the Kazakh language. "In that place wholly faraway", based on a Kazakh folk song, is very popular outside the Kazakh regions, especially in the Far Eastern countries of China, Japan and Korea.

At least one million Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other ethnic Muslims in Xinjiang have been detained in mass detention camps, termed "reeducation camps", aimed at changing the political thinking of detainees, their identities, and their religious beliefs.[71][72][73]

Mongolia

In the 19th century, the advance of the Russian Empire troops pushed Kazakhs to neighboring countries. In around 1860, part of the Middle Jüz Kazakhs came to Mongolia and were allowed to settle down in Bayan-Ölgii, Western Mongolia and for most of the 20th century they remained an isolated, tightly knit community. Ethnic Kazakhs (so-called Altaic Kazakhs or Altai-Kazakhs) live predominantly in Western Mongolia in Bayan-Ölgii Province (88.7% of the total population) and Khovd Province (11.5% of the total population, living primarily in Khovd city, Khovd sum and Buyant sum). In addition, a number of Kazakh communities can be found in various cities and towns spread throughout the country. Some of the major population centers with a significant Kazakh presence include Ulaanbaatar (90% in khoroo #4 of Nalaikh düüreg,[74] Töv and Selenge provinces, Erdenet, Darkhan, Bulgan, Sharyngol (17.1% of population total)[75] and Berkh cities.

| 1956 | % | 1963 | % | 1969 | % | 1979 | % | 1989 | % | 2000 | % | 2010[6] | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36,729 | 4.34 | 47,735 | 4.69 | 62,812 | 5.29 | 84,305 | 5.48 | 120,506 | 6.06 | 102,983 | 4.35 | 101,526 | 3.69 |

Uzbekistan

400,000 Kazakhs live in Karakalpakstan and 100,000 in Tashkent province. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the vast majority of Kazakhs are returning to Kazakhstan, mainly to Manghistau Oblast. Most Kazakhs in Karakalpakstan are descendants of one of the branches of "Junior juz" (Kişi juz) – Adai tribe.

Iran

Iran bought Kazakh slaves who were falsely masqueraded as Kalmyks by slave dealers from the Khiva and Turkmens.[77][78]

Kazakhs of the Aday tribe inhabited the border regions of the Russian Empire with Iran since the 18th century. The Kazakhs made up 20% of the population of the Trans-Caspian region according to the 1897 census. As a result of the Kazakhs' rebellion against the Russian Empire in 1870, a significant number of Kazakhs became refugees in Iran.

Iranian Kazakhs live mainly in Golestan Province in northern Iran.[79] According to ethnologue.org, in 1982 there were 3000 Kazakhs living in the city of Gorgan.[80][81] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the number of Kazakhs in Iran decreased because of emigration to their historical motherland.[82]

Afghanistan

Afghan Kypchaks are Aimak (Taymani) tribe of Kazakh origin that can be found in Obe District to the east of the western Afghan province of Herat, between the rivers Farāh Rud and Hari Rud. There are approximately 440,000 Afghan Kipchaks.

Turkey

Turkey received refugees from among the Pakistan-based Kazakhs, Turkmen, Kirghiz, and Uzbeks numbering 3,800 originally from Afghanistan during the Soviet–Afghan War.[83] Kayseri, Van, Amasya, Çiçekdağ, Gaziantep, Tokat, Urfa, and Serinyol received via Adana the Pakistan-based Kazakh, Turkmen, Kirghiz, and Uzbek refugees numbering 3,800 with UNHCR assistance.[84]

In 1954 and 1969 Kazakhs migrated into Anatolia's Salihli, Develi and Altay regions.[85] Turkey became home to refugee Kazakhs.[86]

The Kazakh Turks Foundation (Kazak Türkleri Vakfı) is an organization of Kazakhs in Turkey.[87]

Culture

Music

One of the most commonly used traditional musical instruments of the Kazakhs is the dombra, a plucked lute with two strings. It is often used to accompany solo or group singing. Another popular instrument is kobyz, a bow instrument played on the knees. Along with other instruments, both instruments play a key role in the traditional Kazakh orchestra. A notable composer is Kurmangazy, who lived in the 19th century. After studying in Moscow, Gaziza Zhubanova became the first woman classical composer in Kazakhstan, whose compositions reflect Kazakh history and folklore. A notable singer of the Soviet epoch is Roza Rymbaeva, she was a star of the trans-Soviet-Union scale. A notable Kazakh rock band is Urker, performing in the genre of ethno-rock, which synthesises rock music with the traditional Kazakh music.

Notable Kazakhs

See also

References

- March 2018, Staff Report in Nation on 31 (31 March 2018). "Kazakhstan's population tops 18 million". The Astana Times. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике. Этнодемографический сборник Республики Казахстан 2014".

- Census 2000 counts 1.25 trillion Kazakhs The Kazak Ethnic Group, later the Kazakh population had higher birth rate, but some assimilation processes were present too. Estimates made after the 2000 Census claim Kazakh population share growth (was 0.104% in 2000), but even if that value were preserved at 0.104%, it would be no less than 1.4 million in 2008.

- Kazakh population share was constant at 4.1% in 1959–1989, CIA estimates that declined to 3% in 1996. Official Uzbekistan estimation (E. Yu. Sadovskaya "Migration in Kazakhstan in the beginning of the 21st century: main tendentions and perspectives" ISBN 978-9965-593-01-7) in 1999 was 940,600 Kazakhs or 3.8% of total population. If Kazakh population share was stable at about 4.1% (not taking into account the massive repatriation of ethnic Kazakhs (Oralman) to Kazakhstan estimated over 0.6 million) and the Uzbekistan population in the middle of 2008 was 27.3 million, the Kazakh population would be 1.1 million. Using the CIA estimate of the share of Kazakhs (3%), the total Kazakh population in Uzbekistan would be 0.8 million

- "Russia National Census 2010".

- Mongolia National Census 2010 Provision Results. National Statistical Office of Mongolia Archived 15 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Mongolian.)

- In 2009 National Statistical Committee of Kyrgyzstan. National Census 2009 Archived 8 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Place of birth for the foreign-born population in the United States, Universe: Foreign-born population excluding population born at sea, 2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- "Казахское общество Турции готово стать объединительным мостом в крепнущей дружбе двух братских народов – лидер общины Камиль Джезер". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- "Казахи "ядерного" Ирана". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ""Казахи доказали, что являются неотъемлемой частью иранского общества и могут служить одним из мостов, связующих две страны" – представитель диаспоры Тойжан Бабык". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Population data". czso.cz.

- Ukrainian population census 2001 : Distribution of population by nationality. Retrieved 23 April 2009

- "UAE´s population – by nationality". BQ Magazine. 12 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "Bevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit und Geburtsland". Statistik Austria. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- population census 2009 Archived 3 February 2012 at WebCite: National composition of the population.

- "Kasachische Diaspora in Deutschland. Botschaft der Republik Kasachstan in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland" (in German). botschaft-kaz.de. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016.

- Farchy, Jack (9 May 2016). "Kazakh language schools shift from English to Chinese". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Students learn Chinese to hone their job prospects – World – Chinadaily.com.cn". China Daily. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "The Kazak Ethnic Group". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Kazakhstan population census 2009 Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Religion and expressive culture – Kazakhs". Everyculture.com. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". The World’s Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2013

- Итоги национальной переписи населения 2009 года (Summary of the 2009 national census) (in Russian). Agency of Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Religion in Kazakhstan". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Togan, Z. V. (1992). "The Origins of the Kazaks and the Uzbeks". Central Asian Survey. 11 (3). doi:10.1080/02634939208400781.

- Barthold, V. V. (1962). Four Studies on the History of Central Asia. vol.&thinsp, 3. Translated by V. & T. Minorsky. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 129.

- Olcott, Martha Brill (1995). The Kazakhs. Hoover Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8179-9351-1. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- Уюк-Туран [Uyuk-Turan] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 February 2006.

- Yudin, Veniamin P. (2001). Центральная Азия в 14–18 веках глазами востоковеда [Central Asia in the eyes of 14th–18th century Orientalists]. Almaty: Dajk-Press. ISBN 978-9965-441-39-4.

- Subtelny, Maria Eva (1988). "Centralizing Reform and Its Opponents in the Late Timurid Period". Iranian Studies. Taylor & Francis, on behalf of the International Society of Iranian Studies. 21 (1/2: Soviet and North American Studies on Central Asia): 123–151. doi:10.1080/00210868808701712. JSTOR 4310597.

- Bregel, Yuri (1982). "Abu'l-Kayr Khan". Encyclopædia Iranica. 1. Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 331–332.

- Barthold, V. V. (1962). "History of the Semirechyé". Four Studies on the History of Central Asia. vol.&thinsp, 1. Translated by V. & T. Minorsky. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 137–65.

- Постановление ЦИК и СНК КазАССР № 133 от 5 February 1936 о русском произношении и письменном обозначении слова «казак»

- "Cossack". Online Etymology Dictionary. Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- "Cossack | Russian and Ukrainian people". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- Russian, Mongolia, China in the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. Vol II. Baddeley (1919, MacMillan, London). Reprint – Burt Franklin, New York. 1963 p. 59

- Atabaki, Touraj. Central Asia and the Caucasus: transnationalism and diaspora, pg. 24

- Ibn Athir, volume 8, pg. 396

- Khodarkovsky, Michael. Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500–1800, pg. 39.

- Ember, Carol R. and Melvin Ember. Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures, pg. 572

- Hunter, Shireen. "Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security", pg. 14

- Farah, Caesar E. Islam: Beliefs and Observances, pg. 304

- Farah, Caesar E. Islam: Beliefs and Observances, pg. 340

- Page, Kogan. Asia and Pacific Review 2003/04, pg. 99

- Atabaki, Touraj. Central Asia and the Caucasus: transnationalism and diaspora.

- inform.kz | 154837 Archived 20 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Robbeets 2017, pp. 216-218.

- Robbeets 2020.

- Nelson et al. 2020.

- Li et al. 2020.

- Uchiyama et al. 2020.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, pp. 4–5. "These results suggest that Turkic cultural customs were imposed by an East Asian minority elite onto central steppe nomad populations... The wide distribution of the Turkic languages from Northwest China, Mongolia and Siberia in the east to Turkey and Bulgaria in the west implies large-scale migrations out of the homeland in Mongolia.

- Lee & Kuang 2017, p. 197. "Both Chinese histories and modern dna studies indicate that the early and medieval Turkic peoples were made up of heterogeneous populations. The Turkicisation of central and western Eurasia was not the product of migrations involving a homogeneous entity, but that of language diffusion."

- "Полиморфизм митохондриальной ДНК в казахской популяции".

- ""aDNA from the Sargat Culture" by Casey C. Bennett and Frederika A. Kaestle". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Omer Gokcumen, Matthew C. Dulik, Athma A. Pai, Sergey I. Zhadanov, Samara Rubinstein, Ludmila P. Osipova, Oleg V. Andreenkov, Ludmila E. Tabikhanova, Marina A. Gubina, Damian Labuda, and Theodore G. Schurr, "Genetic Variation in the Enigmatic Altaian Kazakhs of South-Central Russia: Insights into Turkic Population History." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 136:278–293 (2008). DOI 10.1002/ajpa.20802

- Zerjal T, Wells RS, Yuldasheva N, Ruzibakiev R, Tyler-Smith C (September 2002). "A genetic landscape reshaped by recent events: Y-chromosomal insights into central Asia". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71 (3): 466–82. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- Kazakh Family Tree DNA-project – Y-DNA – https://www.familytreedna.com/public/alash/default.aspx?section=yresults

- E. E. Ashirbekov, D. M. Botbaev, A. M. Belkozhaev, A. O. Abayldaev, A. S. Neupokoeva, J. E. Mukhataev, B. Alzhanuly, D. A. Sharafutdinova, D. D. Mukushkina, M. B. Rakhymgozhin, A. K. Khanseitova, S. A. Limborska, N. A. Aytkhozhina, "Distribution of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups of the Kazakh from the South Kazakhstan, Zhambyl, and Almaty Regions." Reports of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan, ISSN 2224-5227, Volume 6, Number 316 (2017), 85 – 95.

- "Ethnic composition of Russia (national censuses)". Demoscope.ru. 27 May 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volumes 276–278. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

A group of Kazakhs, originally numbering over 20000 people when expelled from Sinkiang by Sheng Shih-ts'ai in 1936, was reduced, after repeated massacres by their Chinese coreligionists under Ma Pu-fang, to a scattered 135 people.

- Hsaio-ting Lin (1 January 2011). Tibet and Nationalist China's Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928–49. UBC Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-7748-5988-2.

- Hsaio-ting Lin (1 January 2011). Tibet and Nationalist China's Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928–49. UBC Press. pp. 231–. ISBN 978-0-7748-5988-2.

- Blackwood's Magazine. William Blackwood. 1948. p. 407.

- Devlet, Nadir. STUDIES IN THE POLITICS, HISTORY AND CULTURE OF TURKIC PEOPLES. p. 192.

- Linda Benson (1988). The Kazaks of China: Essays on an Ethnic Minority. Ubsaliensis S. Academiae. p. 195. ISBN 978-91-554-2255-4.

- "Central Asians Organize to Draw Attention to Xinjiang Camps". The Diplomat. 4 December 2018.

- "Majlis Podcast: The Repercussions Of Beijing's Policies In Xinjiang". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL). 9 December 2018.

- "Families Of The Disappeared: A Search For Loved Ones Held In China's Xinjiang Region". NPR. 12 November 2018.

- Education of Kazakh children: A situation analysis. Save the Children UK, 2006

- Sharyngol city review

- "Монгол улсын ястангуудын тоо, байршилд гарч буй өөрчлөлтуудийн асуудалд" М.Баянтөр, Г.Нямдаваа, З.Баярмаа pp.57–70 Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- electricpulp.com. "BARDA and BARDA-DĀRI iv. From the Mongols – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

- Keith Edward Abbott; Abbas Amanat (1983). Cities & trade: Consul Abbott on the economy and society of Iran, 1847–1866. Published by Ithaca Press for the Board of the Faculty of Oriental Studies, Oxford University. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-86372-006-2.

- "گلستان". Anobanini.ir. Archived from the original on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- "Ethnologue report for Iran". Ethnologue.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- http://www.golestanstate.ir/layers.aspx?quiz=page&PageID=23 Archived 7 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "قزاق". Jolay.blogfa.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- News Review on South Asia and Indian Ocean. Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses. July 1982. p. 861.

- Problèmes politiques et sociaux. Documentation française. 1982. p. 15.

- Espace populations sociétés. Université des sciences et techniques de Lille, U.E.R. de géographie. 2006. p. 174.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. CUP Archive. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. CUP Archive. pp. 236–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.

- "Kazakh Turks Foundation Official Website". Kazak Türkleri Vakfı Resmi Web Sayfası. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kazakh people. |

- World Association of the Kazakhs

- Kazakh tribes

- ‘Contemporary Falconry in Altai-Kazakh in Western Mongolia’The International Journal of Intangible Heritage (vol.7), pp. 103–111. 2012.

- ‘Ethnoarhchaeology of Horse-Riding Falconry’, The Asian Conference on the Social Sciences 2012 – Official Conference Proceedings, pp. 167–182. 2012.

- ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Arts and Knowledge for Coexisting with Golden Eagles: Ethnographic Studies in “Horseback Eagle-Hunting” of Altai-Kazakh Falconers’, The International Congress of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, pp. 307–316. 2012.

- ‘Ethnographic Study of Altaic Kazakh Falconers’, Falco: The Newsletter of the Middle East Falcon Research Group 41, pp. 10–14. 2013.

- ‘Ethnoarchaeology of Ancient Falconry in East Asia’, The Asian Conference on Cultural Studies 2013 – Official Conference Proceedings, pp. 81–95. 2013.

- Soma, Takuya. 2014. 'Current Situation and Issues of Transhumant Animal Herding in Sagsai County, Bayan Ulgii Province, Western Mongolia', E-journal GEO 9(1): pp. 102–119.

- Soma, Takuya. 2015. Human and Raptor Interactions in the Context of a Nomadic Society: Anthropological and Ethno-Ornithological Studies of Altaic Kazakh Falconry and its Cultural Sustainability in Western Mongolia. University of Kassel Press, Kassel (Germany) ISBN 978-3-86219-565-7.