Operation Lüttich

Operation Lüttich was a codename given to a German counter-attack during the Battle of Normandy, which took place around the American positions near Mortain in northwestern France from 7 August to 13 August 1944. (Lüttich is the German name for the city of Liège in Belgium, where the Germans had won a victory in the early days of August 1914 during World War I.) The offensive is also referred to in American and British histories of the Battle of Normandy as the Mortain counterattack.

| Battle of Mortain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Normandy | |||||||

German armour destroyed during Operation Lüttich, August 1944 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Omar Bradley | Günther von Kluge | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5 Infantry Divisions 3 Armored combat commands USAAF Ninth Air Force RAF Second Tactical Air Force |

3 Panzer Divisions 2 Infantry Divisions 5 Panzer or Infantry battlegroups 150 tanks and assault guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~10,000 casualties 2,000–3,000 killed |

unknown number of infantry 120 tanks and assault guns destroyed or damaged | ||||||

The assault was ordered by Adolf Hitler, to eliminate the gains made by the First United States Army during Operation Cobra and the subsequent weeks, and by reaching the coast in the region of Avranches at the base of the Cotentin peninsula, cut off the units of the Third United States Army which had advanced into Brittany.

The main German striking force was the XLVII Panzer Corps, with one and a half SS Panzer Divisions and two Heer Panzer Divisions. Although they made initial gains against the defending U.S. VII Corps, they were soon halted and the Allies inflicted severe losses on the attacking troops, eventually destroying most of the German tanks involved in the attack.[1] Although fighting continued around Mortain for six days, the American forces had regained the initiative within a day of the opening of the German attack.

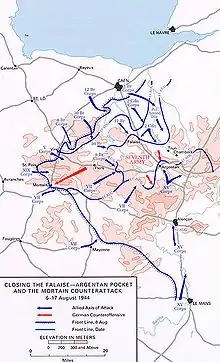

As the German commanders on the spot had warned Hitler in vain, there was little chance of the attack succeeding, and the concentration of their armoured reserves at the western end of the front in Normandy soon led to disaster, as they were outflanked to their south and the front to their east collapsed, resulting in many of the German troops in Normandy being trapped in the Falaise Pocket.

Background

On 25 July 1944, following six weeks of attritional warfare along a stalemated front, American forces under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley mounted an attack code-named Operation Cobra, which broke through the German defenses near Saint-Lô.[2] Almost the entire western half of the German front in Normandy collapsed, and on 1 August, American forces captured Avranches.[2] With the capture of this town at the base of the Cotentin peninsula, and an intact bridge at Pontaubault nearby, the American forces had "turned the corner"; the German front could no longer be anchored against the sea at its western end and American forces could advance west and south into Brittany.[2][3] The U.S. Third Army, commanded by Lieutenant General George S. Patton, was activated the same day.[4] Despite German air attacks against the bridge at Pontaubault, Patton pushed no less than seven divisions across it during the next three days, and units of his army began advancing almost unopposed towards the Brittany ports.[5]

Beginning on 30 July, the British Second Army, under Lieutenant-General Miles C. Dempsey, mounted a supporting attack (code-named Operation Bluecoat) on the eastern flank of the American armies. Much of the German armored reserves being rushed west to halt the American breakthrough were diverted to face this new threat.[2] Meanwhile, the U.S. continued its attacks to widen the corridor around Avranches. Although the Germans held the vital road junction of Vire, U.S. VII Corps, under Major General J. Lawton Collins, captured Mortain, 19 miles (31 km) east of Avranches, on 3 August.

The next day, although U.S. VIII Corps continued to advance west through Brittany toward the ports of Brest and Lorient, Bradley ordered Patton to drive eastward with the main body of the U.S. Third Army, around the open German flank and into the German rear areas.[6] U.S. XV Corps advanced no less than 75 mi (121 km) during the next three days, and by 7 August they were approaching Le Mans, formerly the location of the headquarters of the German 7th Army, and still an important logistic center.

German command and decisions

Generalfeldmarshall Günther von Kluge was the German supreme commander in the West. After Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel was injured by Allied aircraft on 17 July, Kluge also took over direct command of Army Group B, the formation conducting the battle in Normandy. He had warned Hitler on 22 July that the collapse of the front was imminent, but Hitler continued to order him to stand fast.

On 2 August, Hitler sent a directive to Kluge ordering "an immediate counter-attack between Mortain and Avranches".[7] General Walter Warlimont—the Deputy Chief of Staff at OKW, the German armed forces headquarters—was also sent to Kluge's headquarters to ensure these orders were complied with.[6] Kluge suggested that there was no chance of success, and the German forces in Normandy should retire to the Seine River, pivoting on the intact defences south of Caen, but on 4 August, Hitler categorically ordered the attack to be launched. He demanded that eight of the nine Panzer Divisions in Normandy be used in the attack, and that the Luftwaffe commit its entire reserve, including 1,000 fighters.[8] According to Hitler, three qualifications had to be met for the attack to proceed. "Von Kluge must believe in it. He must be able to detach enough armour from the main front in Normandy to create an effective striking force, and he must achieve surprise".[9]

Although ordered to wait "until every tank, gun and plane was assembled", Kluge and SS General Paul Hausser (commanding the German 7th Army, which held the western part of the front) decided to attack as soon as possible, before the overall situation deteriorated further. The main striking force assigned was the XLVII Panzer Corps, commanded by General Hans Freiherr von Funck. Instead of eight Panzer Divisions, only four—one of them incomplete—could be relieved from their defensive tasks and assembled in time; the 2nd Panzer Division, 116th Panzer Division, the 2nd SS Panzer Division and part of the 1st SS Panzer Division, with a total of about 300 tanks.[10] The Panzer Corps was supported by two Infantry Divisions and five Kampfgruppen, formed from the remnants of the Panzer Lehr Division[1] and four equally battered infantry divisions.

Kluge ordered the attack to be mounted on the night of 6/7 August. To avoid alerting American forces to the attack, there would be no preparatory artillery bombardments.[11] The intention was to hit the U.S. 30th Infantry Division, commanded by Major-General Leland Hobbs, east of Mortain,[11] then cut through American defenses to reach the coast. Had surprise been achieved, the attack might well have succeeded,[11] but Allied decoders at Ultra had intercepted and decrypted the orders for Operation Lüttich by August 4.[12] As a result, Bradley was able to obtain air support from both the US 9th Air Force and the RAF.[13]

German attacks

At 22:00 on 6 August, von Funck reported that his troops were still not concentrated, and the commander of the 116th Panzer Division "had made a mess of things".[14] In fact, this officer (Gerhard von Schwerin) had been so pessimistic about the operation that he had not even ordered his tank units to take part.[1] This delay disjointed the German attack, but on the German left flank, the SS Panzer troops attacked the positions of the American 30th Infantry Division east of Mortain shortly after midnight.[11] The Germans achieved temporary surprise, as the Ultra documents had arrived at U.S. First Army Headquarters too late to alert the troops to the immediate assault.[15] They briefly captured Mortain but were unable to breach the lines of the 30th Division, as the 2nd Battalion of the 120th Infantry Regiment commanded Hill 314, the dominant feature around Mortain.[16] Although cut off, they were supplied by parachute drops. Of the 700 men who defended the position until 12 August, over 300 were killed or wounded.[15]

To the north, the 2nd Panzer Division attacked several hours later, aiming south-west toward Avranches. It managed to penetrate several miles into the American lines, before being stopped by the 35th Infantry Division and a combat command of the 3rd Armored Division only 2 mi (3.2 km) short of Avranches.[1][15] The German High Command ordered the attacks to be renewed before the afternoon, so that Avranches could be taken.[17]

Allied air strikes—the offensive stalls

By noon of 7 August, the early morning fog had dispersed, and large numbers of Allied aircraft appeared over the battlefield. With the advance knowledge of the attack provided by Ultra, the U.S. 9th Air Force had been reinforced by the RAF Second Tactical Air Force.[11] Despite assurances by the Luftwaffe that German forces would have adequate air support,[13] the Allied aircraft quickly achieved complete control of the airspace over Mortain.[15] The Luftwaffe reported that its fighters were engaged by Allied aircraft from the moment they took off, and were unable even to reach the battlefield.[18] In the open ground east of Mortain, the German Panzers became exposed targets, especially for rocket-firing Hawker Typhoon fighter bombers of the RAF.[15]

Traditional accounts of the Allied fighter bomber attacks in the Battle of Mortain accepted the claims of the pilots of over two hundred destroyed German tanks. However, subsequent detailed studies of the battlefield showed that most of the destroyed German armor were knocked out by gunfire from ground forces and that the main effect of the Allied air attacks had been to destroy the unarmored vehicles and troops in the German offensive, as well as forcing the German armor to disperse to cover. The accuracy of the rockets and bombs of the Allied fighter-bombers was simply too poor to destroy more than a few of the German tanks, although fear of being incinerated inside a tank should a rocket or bomb actually strike a tank did cause some of the inexperienced German tank crews to abandon their tanks intact while under air attack.[19] In one British study, it was found that the average Typhoon pilot firing a barrage of all eight rockets had only a four percent chance of striking a target the size of a tank.[20]

American counter-moves

Through 7 August, American troops had continued to press south near Vire, on the right flank of the German attack.[15] The 116th Panzer Division—which was supposed to advance in this sector—was actually driven back. In the afternoon, the 1st SS and 116th Panzer Divisions made renewed attacks, but the flanks of the Mortain positions had been sealed off, allowing the American VII Corps to contain the German advance.[15]

Meanwhile, Bradley had sent two armoured combat commands against the German southern (left) flank. On 8 August, one of these (from the U.S. 2nd Armored Division) was attacking the rear of the two SS Panzer Divisions. Although fighting would continue around Mortain for several more days, there was no further prospect of any German success.[11][21] The Germans issued orders to go on to the defensive along the entire front, but poorly communicated orders resulted in this being impossible to achieve, with some German forces retreating, and others preparing to hold their ground.[22]

As the U.S. First Army counter-attacked German units near Mortain, units of Patton's 3rd Army were advancing unchecked through the open country to the south of the German armies, and had taken Le Mans on 8 August.[18] The same day, the First Canadian Army attacked the weakened German positions south of Caen in Operation Totalize and threatened to break through to Falaise, although this attack stalled after two days. In desperation, Hitler ordered the attacks against Mortain to be renewed with greater intensity, demanding that the 9th Panzer Division, almost the only formation opposing Patton's advance east from Le Mans, be transferred to Mortain to take part in the attack.[11] General Heinrich Eberbach—commander of Panzergruppe West—was ordered to form a new headquarters, named "Panzer Group Eberbach", to command the renewed offensive.[23] Kluge—who feared he was about to be implicated by the Gestapo in the 20 July Plot—acquiesced in this apparently suicidal order.[24] Eberbach's proposed counter-attack was soon overtaken by events, and was never mounted.[24]

Aftermath

By 13 August, the offensive had fully halted, with German forces being driven out of Mortain. The Germans had lost 120 tanks and assault guns to Allied counter-attacks and air strikes, more than two-thirds of their committed total.[25][26][1] As Hitler ordered German forces in Normandy to hold their positions,[24] the U.S. VII and XV Corps were swinging east and north toward Argentan.[24] The German attack west left the 7th Army and Panzergruppe West in danger of being encircled by Allied forces. As American forces advanced on Argentan, British and Canadian forces advanced on Falaise, threatening to cut off both armies in the newly formed Falaise Pocket.[24]

Although American casualties in Operation Lüttich were significantly lighter than in previous operations, certain sectors of the front, notably the positions held by the 30th Division around Mortain, took severe casualties. By the end of 7 August alone, nearly 1,000 men of the 30th Division had been killed.[21] Estimates for American casualties from 6–13 August vary from 2,000-3,000 fatalities, with an unknown number of wounded.[27]

On 14 August, Canadian forces launched Operation Tractable, in conjunction with American movements northwards to Chambois. On 19 August, a brigade of the Polish 1st Armoured Division linked up with forces of the 90th U.S. Infantry Division, sealing off some 50,000 German troops in the pocket. By 21 August, German attempts to reopen the gap had been thwarted, and all German troops trapped in the pocket surrendered to Allied forces, effectively putting an end to the German 7th Army.[28]

Footnotes

- "Operation Lüttich". Memorial Mont-Ormel. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- Van der Vat, p.163

- D'Este, p.409

- D'Este, p.408

- Wilmot, p.399

- Wilmot, p.400

- D'Este, p. 414

- Wilmot, p.401

- Lewin, p. 338

- Fey, p.145

- Van Der Vat, p.164

- D'Este, p.415

- D'Este, p.416

- Wilmot, p.402

- D'Este, p.419

- D'Este, p.418

- Fey, p.146

- Wilmot, p.404

- Gooderson, 1997 pp. 111–117

- Gooderson, 1997 p. 76

- D'Este, p. 420

- Fey, p.147

- Wilmot, p. 414

- Cawthorne, p.125

- Napier 2015, p. 324.

- Fey, p.150

- Cawthorne, p. 126

- Cawthorne, p. 129

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Mortain. |

- Buisson, Jules and Gilles (1946) Mortain et sa bataille, 2–13 août 1944. French, Imprimerie Simon, Rennes; Le Livre d'Histoire, Paris, 2004 ISBN 2-84373-533-5

- Buisson, Gilles, and Blouet, Léon (1954) La Montjoie héroïque; l'ermitage Saint-Michel au cours des siècles; la défense de la cote 314 pendants les combats d'août 1944. French, Imprimerie du Mortainais

- Buisson, Gilles (1954) L'Epopée du bataillon perdu. French, Imprimerie du Mortainais; (1975), Historame, hors série n° 2

- Cawthorne, Nigel (2005) Victory in World War II. Arcturus Publishing. ISBN 1-84193-351-1

- D'Este, Carlo (1983). Decision in Normandy. Konecky & Konecky, New York. ISBN 1-56852-260-6

- Fey, William [1990] (2003). Armor Battles of the Waffen-SS. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-2905-5

- Gooderson, Ian 1997 Air Power at the Battlefront: Allied Close Air Support in Europe 1943–45 Frank Cass, London. ISBN 0-71464-680-6

- Lewin, Ronald (1978). Ultra Goes to War. McGraw-Hill, New York. ISBN 0-07-037453-8

- Napier, Stephen (2015). The Armoured Campaign in Normandy June–August 1944. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 9780750964739.

- Van Der Vat, Dan (2003). D-Day; The Greatest Invasion, A People's History. Madison Press. ISBN 1-55192-586-9.

- Weiss, Robert (1998). Enemy North, South, East, West. Strawberry hill Press. ISBN 0894071238.

- Wilmot, Chester; Christopher Daniel McDevitt [1952] (1997). The Struggle For Europe. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-85326-677-9.