Operation Praying Mantis

Operation Praying Mantis was an attack on 18 April 1988, by U.S. forces within Iranian territorial waters in retaliation for the Iranian mining of the Persian Gulf during the Iran–Iraq War and the subsequent damage to an American warship.

| Operation Praying Mantis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Iran–Iraq War | |||||||

The Iranian frigate Sahand (1969) attacked by aircraft of U.S. Navy Carrier Air Wing 11 after the guided missile frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts struck an Iranian mine | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 aircraft carrier 1 amphibious transport dock 4 destroyers 1 guided missile cruiser 3 frigates |

2 frigates 1 gunboat 6 Boghammar speedboats (estimated) 2 F-4 fighters 2 platforms | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 killed 1 helicopter crashed |

1 frigate sunk (45 crew killed)[1] 1 gunboat sunk (11 crew killed)[1] 3 speedboats sunk 1 frigate crippled 2 platforms destroyed[2] 1 fighter damaged Total: 56 killed 6 ships sunk | ||||||

| |||||||

On 14 April, the guided missile frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts struck a mine while deployed in the Persian Gulf as part of Operation Earnest Will, the 1987–88 convoy missions in which U.S. warships escorted reflagged Kuwaiti oil tankers to protect them from Iranian attacks. The explosion blew a 4.5 m (15-foot) hole in the Samuel B. Roberts's hull and nearly sank it. The crew saved their ship with no loss of life, and the Samuel B. Roberts was towed to Dubai, United Arab Emirates on 16 April. After the mining, U.S. Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) divers recovered other mines in the area. When the serial numbers were found to match those of mines seized along with the Iran Ajr the previous September, U.S. military officials planned a retaliatory operation against Iranian targets in the Persian Gulf.

According to Bradley Peniston, the attack by the U.S. helped pressure Iran to agree to a ceasefire with Iraq later that summer, ending the eight-year conflict between the Persian Gulf neighbors.[3]

On 6 November 2003, the International Court of Justice ruled that "the actions of the United States of America against Iranian oil platforms on 19 October 1987 (Operation Nimble Archer) and 18 April 1988 (Operation Praying Mantis) cannot be justified as measures necessary to protect the essential security interests of the United States of America." However, the International Court of Justice dismissed Iran's claim that the attack by United States Navy was a breach of the 1955 Treaty of Amity between the two countries as it only pertained to vessels, not platforms.[4]

This battle was the largest of the five major U.S. surface engagements since the Second World War, which also include the Battle of Chumonchin Chan during the Korean War, the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the Battle of Dong Hoi during the Vietnam War, and the Action in the Gulf of Sidra in 1986. It also marked the U.S. Navy's first exchange of anti-ship missiles with opposing ships and the only occasion since World War II on which the US Navy sank a major surface combatant.

By the end of the operation, U.S. air and surface units had sunk, or severely damaged, half of Iran's operational fleet.

Battle

On 18 April, the U.S. Navy attacked with several groups of surface warships, plus aircraft from the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, and her cruiser escort, USS Truxtun. The action began with coordinated strikes by two surface groups.

One Surface Action Group, or SAG, consisting of the destroyers USS Merrill (including embarked LAMPS MK I Helicopter Detachment HSL-35 Det 1) and USS Lynde McCormick, plus the amphibious transport dock USS Trenton and its embarked Marine Air-Ground Task Force (Contingency MAGTF 2-88 from Camp LeJeune, NC)[5] and the LAMPS (Light Airborne MultiPurpose System) Helicopter Detachment (HSL-44 Det 5) from USS Samuel B. Roberts, was ordered to destroy the guns and other military facilities on the Sassan oil platform. At 8am, the SAG commander, who was also the commander of Destroyer Squadron 9, ordered the Merrill to radio a warning to the occupants of the platform, telling them to abandon it. The SAG waited 20 minutes, then opened fire. The oil platform fired back with twin-barrelled 23 mm ZU-23 guns. The SAG's guns eventually disabled some of the ZU-23s, and platform occupants radioed a request for a cease-fire. The SAG complied. After a tug carrying more personnel had cleared the area, the ships resumed exchanging fire with the remaining ZU-23s, and ultimately disabled them. Cobra helicopters completed the destruction of enemy resistance. The Marines boarded the platform, and recovered a single wounded survivor (who was transported to Bahrain), some small arms, and intelligence. The Marines planted explosives, left the platform, and detonated them. The SAG was then ordered to proceed north to the Rakhsh oil platform to destroy it.

As the SAG departed the Sassan oil field, two Iranian F-4s made an attack run, but broke off when Lynde McCormick locked its fire control radar on the aircraft. Halfway to the Rahksh oil platform, the attack was called off in an attempt to ease pressure on the Iranians and signal a desire for de-escalation.

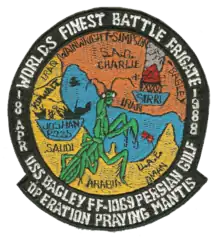

The other group, which included the guided missile cruiser USS Wainwright and frigates USS Simpson and USS Bagley, attacked the Sirri oil platform. Navy SEALs were assigned to capture, occupy and destroy the Sirri platform but due to heavy pre-assault damage from naval gunfire, it was determined that an assault was not required.

Iran responded by dispatching Boghammar speedboats to attack various targets in the Persian Gulf, including the American-flagged supply ship Willie Tide, the Panamanian-flagged oil rig Scan Bay and the British tanker York Marine. All of these vessels were damaged in different degrees. After the attacks, A-6E Intruder aircraft launched from USS Enterprise, were directed to the speedboats by an American frigate. The two VA-95, aircraft, piloted by "Lizards" Lieutenant Commander James Engler and Lieutenant Paul Webb, dropped Rockeye cluster bombs on the speedboats, sinking one and damaging several others, which then fled to the Iranian-controlled island of Abu Musa.[6]

Action continued to escalate. Iranian fast attack craft Joshan, an Iranian Combattante II Kaman-class fast attack craft, challenged USS Wainwright and Surface Action Group Charlie. The commanding officer of Wainwright directed a final warning (of a series of warnings) stating that Joshan was to "stop your engines, abandon ship, I intend to sink you". Joshan responded by firing a Harpoon missile at them.[7] The missile was successfully lured away by chaff.[8] USS Simpson responded to the challenge by firing four Standard missiles, while Wainwright followed with one Standard missile.[9] All missiles hit and destroyed the Iranian ship's superstructure but did not immediately sink it, so Bagley fired a Harpoon of its own. The missile did not find the target. SAG Charlie closed on Joshan, with Simpson, then Bagley and Wainwright firing guns to sink the crippled Iranian ship.[7]

Two Iranian F-4 Phantom fighters were orbiting about 48 km (26 nmi) away when Wainwright decided to drive them away. Wainwright fired two Extended Range Standard missiles, one of which detonated near an F-4, blowing off part of its wing and peppering the fuselage with shrapnel. The F-4s withdrew, and the Iranian pilot landed his damaged airplane at Bandar Abbas.[9]

Fighting continued when the Iranian frigate IRIS Sahand departed Bandar Abbas and challenged elements of an American surface group. The frigate was spotted by two A-6Es from VA-95 while they were flying surface combat air patrol for USS Joseph Strauss.

Sahand fired missiles at the A-6Es, which replied with two Harpoon missiles and four laser-guided Skipper missiles. Joseph Strauss fired a Harpoon. Most, if not all of the shots scored hits, causing heavy damage and fires. Fires blazing on Sahand's decks eventually reached her munitions magazines, causing an explosion that sank her.

Late in the day, the Iranian frigate IRIS Sabalan departed from its berth and fired a surface-to-air missile at several A-6Es from VA-95. The A-6Es then dropped a Mark 82 laser-guided bomb into Sabalan's stack, crippling the ship and leaving it burning. The Iranian frigate, stern partially submerged, was taken in tow by an Iranian tug, and was repaired and eventually returned to service. VA-95's aircraft, as ordered, did not continue the attack. The A-6 pilot who crippled Sabalan, LCDR James Engler, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by Admiral William J. Crowe, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, for the actions against the Sabalan and the Iranian gunboats.[10]

In retaliation for the attacks, Iran fired Silkworm missiles (suspected to be the HY-4 version) from land bases against SAG Delta in the Strait of Hormuz and against USS Gary in the northern central Persian Gulf, but all missed due to the evasive maneuvers and use of decoys by the ships. A missile was probably shot down by Gary's 76 mm (3.0 in) gun. The Pentagon and the Reagan Administration later denied that any Silkworm missile attacks took place, possibly in order to keep the situation from escalating further - as they had promised publicly that any such attacks would merit retaliation against targets on Iranian soil.[11]

Disengagement

Following the attack on Sabalan, U.S. naval forces were ordered to assume a de-escalatory posture, giving Iran a way out and avoiding further combat. Iran took the offer and combat ceased, though both sides remained on alert, and near-clashes occurred throughout the night and into the next day as the forces steamed within the Gulf. Two days after the battle, Lynde McCormick was directed to escort a U.S. oiler out through the Strait of Hormuz, while a Scandinavian-flagged merchant remained near, probably for protection. While the ships remained alert, no hostile indications were received, and the clash was over.

Aftermath

By the end of the operation, American Marines, ships and aircraft had destroyed Iranian naval and intelligence facilities on two inoperable oil platforms in the Persian Gulf, and sank at least three armed Iranian speedboats, one Iranian frigate and one fast attack gunboat. One other Iranian frigate was damaged in the battle.[12] Sabalan was repaired in 1989 and has since been upgraded, and is still in service with the Iranian navy. The fires eventually burned themselves out but the damage to the infrastructure forced the demolition of the Sirri platforms after the war. The site was built up again for oil production by French and Russian oil companies, after buying the drilling rights from the Iranian government.

The U.S. side suffered two casualties, the crew of a Marine Corps AH-1T Sea Cobra helicopter gunship. The Cobra, attached to USS Trenton, was flying reconnaissance from Wainwright and crashed sometime after dark about 15 miles southwest of Abu Musa island. The bodies of the lost personnel were recovered by Navy divers in May, and the wreckage of the helicopter was raised later that month. Navy officials said it showed no sign of battle damage.[13] In his recent book "Tanker War", author Lee Allen Zatarain indicates there was some indication they may have crashed while evading hostile fire from the island.

A month later, the guided missile cruiser USS Vincennes arrived, summoned in haste to protect the frigate Samuel B. Roberts as it was hauled back to the United States. On 3 July, Vincennes shot down Iran Air Flight 655, killing all 290 crew and passengers. The U.S. government claimed that the crew of Vincennes mistook the Iranian Airbus for an attacking F-14 fighter, despite it being a commercial airliner flying a scheduled route. The Iranian government alleged that Vincennes knowingly shot down a civilian aircraft.

International Court of Justice

On 6 November 2003 the International Court of Justice dismissed a claim by Iran and a counter claim by the United States'[4] for reparations for breach of a 1955 'Treaty of Amity' between the two countries. In short the court rejected both claim and counter claim because the 1955 treaty protected only "freedom of trade and navigation between the territories of the parties"[4] and because of the US trade embargo on Iran at the time, no direct trade or navigation between the two was affected by the conflict.

The court did state that "the actions of the United States of America against Iranian oil platforms on 19 October 1987 (Operation Nimble Archer) and 18 April 1988 (Operation Praying Mantis) cannot be justified as measures necessary to protect the essential security interests of the United States of America." The Court ruled that it "...cannot however uphold the submission of the Islamic Republic of Iran that those actions constitute a breach of the obligations of the United States of America under Article X, paragraph 1, of that Treaty, regarding freedom of commerce between the territories of the parties, and that, accordingly, the claim of the Islamic Republic of Iran for reparation also cannot be upheld;".[4]

U.S. naval order of battle

- Officer in Tactical Command: Commander Joint Task Force Middle East (aboard USS Coronado)[14]

- Battle Group Commander: Commander, Cruiser/Destroyer Group Three (aboard USS Enterprise)

Surface Action Group Bravo

- On Scene Commander: Commander, Destroyer Squadron Nine (Embarked on Merrill)

- USS Merrill – destroyer

- USS Lynde McCormick – guided missile destroyer

- USS Trenton – amphibious transport dock

- Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) 2–88 (4 AH-1T, 2 UH-1, 2 CH-46)

- Helicopter AntiSubmarine Squadron 44 Detachment 5 – LAMPS Helicopter (SH-60B)

Surface Action Group Charlie

- OSC: CO, USS Wainwright

- USS Wainwright – guided missile cruiser

- USS Bagley – frigate

- USS Simpson – guided missile frigate

- SEAL platoon

Surface Action Group Delta

- OSC: Commander Destroyer Squadron Twenty Two (Embarked on Jack Williams)

- USS Jack Williams – guided missile frigate

- USS O'Brien – destroyer

- USS Joseph Strauss – guided missile destroyer

Air support

- Elements of Carrier Air Wing Eleven operating from aircraft carrier USS Enterprise

- A-6E & KA-6D Intruders of VA-95 operating from aircraft carrier USS Enterprise

Ship maintenance and support

- USS Samuel Gompers – destroyer tender – performed ship maintenance and repairs operating off the coast of Oman

- USS Wabash – fast attack oiler – provided underway replenishment of fuel, ammunition, and supplies to the USS Enterprise Battle Group

See also

References

- (archived from the original on 26 July 2011)

- "Operation Praying Mantis: Sirri Oil Platform Attack". wikimapia.org. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Peniston, Bradley (2006). No Higher Honor: Saving the USS Samuel B. Roberts in the Persian Gulf. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-661-5. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006., p. 217.

- "Case Concerning Oil Platforms (Islamic Republic of Iran v. United States of America)" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 6 November 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Crist, Dr. David B. (2003). "Before Desert Storm: Marines in the Persian Gulf and the Beginning of U.S. Central Command" (PDF). Fortitudine. 29 (4): 9–12.

- Palmer, Michael (2005). Command at sea: naval command and control since the 16th century.Harvard University Press, p. 310. ISBN 0-674-01681-5

- "The Cutting Edge News". thecuttingedgenews.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- The New York Times. U.S. Strikes 2 Iranian Oil Rigs and Hits 6 Warships in Battles over Minin Sea Lanes in Gulf. 19 April 1988.

- "America's First Clash with Iran: The Tanker War" by Lee Allen Zatarain, Chapter 15: "Stop, Abandon Ship, I Intend to Sink You"

- "ATKRON 95 Operation Praying Mantis". 95thallweatherattack.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- "America's First Clash with Iran: The Tanker War" by Lee Allen Zatarain, Chapter 17: "Multiple Silkworms Inbound"

- Peniston, Bradley (2006). "No Higher Honor: Photos: Operation Praying Mantis". Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- "Will Block Oil Traffic if Its Tankers Are Stopped: Iran". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. 18 May 1988. p. 7.

- "Proceedings, U.S. Naval Institute 66 (May 1989) © 1989 United States Naval Institute The Surface View: Operation Praying Mantis By Captain J. B. Perkins III, U.S. Navy". Strategypage.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

Further reading

- Huchthausen, Peter (2004). America's Splendid Little Wars: A Short History of U.S. Engagements from the Fall of Saigon to Baghdad. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-200465-0.

- Palmer, Michael (2003). On Course to Desert Storm. University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 1-4102-0495-2.

- Peniston, Bradley (2006). No Higher Honor: Saving the USS Samuel B. Roberts in the Persian Gulf. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-661-5. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006.

- Sweetman, Jack (1998). Great American Naval Battles. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-794-5.

- Symonds, Craig L. (2005). Decision at Sea: Five Naval Battles that Shaped American History. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517145-4.

- Taheri, Amir (18 April 2007). "A History Lesson Still Unlearned". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- Wise, Harold Lee (2007). Inside the Danger Zone: The U.S. Military in the Persian Gulf 1987–88. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-970-3.

- Zatarain, Lee Allen (2008). Tanker War, America's First Conflict With Iran, 1987–1988. Drexel Hill: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-932033-84-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Praying Mantis. |