Ornithomancy

Ornithomancy (modern term from Greek ornis "bird" and manteia "divination"; in Ancient Greek: οἰωνίζομαι "take omens from the flight and cries of birds") is the practice of reading omens from the actions of birds followed in many ancient cultures including the Greeks, and is equivalent to the augury employed by the ancient Romans.

| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of religion |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Ornithomancy in some form has been found globally among a wide variety of pre-industrial peoples.[1]

Mediterranean developments

Prophesying by birds appeared among the Hittites in Anatolia, with texts on bird oracles written in Hittite known from the 13th or 14th century,[2] and from whom the Greek practice may derive.[3] It was also familiar to the Etruscans, who may have brought it to Rome.[4]

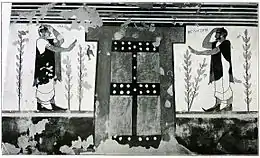

Greek evidence

Ornithomancy dates back to early Greek times, appearing on Archaic vases, as well as in Hesiod and Homer:[5] one notable example from the latter occurs in the Odyssey, when an eagle appears three times, flying to the right, with a dead dove in its talons, an augury interpreted as the coming of Odysseus, and the death of his wife's suitors. Aeschylus has Prometheus claim to have introduced ornithomancy to mankind, by indicating among the birds “those by nature favourable, and those/Sinister”.[6]

Ornithomancy could be spontaneous, or it could be the result of a formal consultation:[7] the seer would face north, and birds on their right — the east, the direction of sunrise — were taken as favourable (the reverse being true of the Roman augur, who by contrast faced south).[8] Although it was mainly the flights and songs of birds that were studied, any action could have been interpreted to either foretell the future or relate a message from the gods.

Roman practice

Omens from observation of the flight of birds were considered with the utmost seriousness by Romans. The practice of ornithomancy by priests called augurs was a branch of Roman national religion from before the founding of the city, which had its own priestly college to supervise its practice.[9]

The word "inauguration" is derived from the Latin noun inauguratio derived from the verb inaugurare which was to "take omens from birds in flight." Since Roman augurs predominantly looked at birds for omens, they were also called auspex ("bird watcher", plural auspices), however they also interpreted thunder, lightning, the behavior of certain animals, and strange events. The phrase "under the auspices" is derived from this need for a favourable reading of the omens by the augurs.[10][11]

Biblical references

Ornithomancy is mentioned several times in the Septuagint version of the Bible. After Joseph discovers the silver bowl he had hidden in his brothers' luggage, he declaims, "Why have ye stolen my silver cup? is it not this out of which my lord drinks? and he divines augury with it."[12] Later in the Septuagint, however, the practice is expressly forbidden.[13]

Cultural echoes

- Lewis Namier introduced his prosopographical study of eighteenth century politics in England with a quotation from Aeschylus on ornithomancy: “I took pains to determine the flight of crook-taloned birds, marking which were of the right by nature, and which were of the left, and what were their ways of living, each after his kind”.[14]

- The magpie counting song is a folklore remnant of ornithomancy.[15]

See also

Notes

- A. Mouton, Luwian Identities (2013) p. 329-30

- Sakuma, Yasuhiko (2013). "Terms of Ornithomancy in Hittite" (PDF). Tokyo University Linguistic Papers. 33: 219–238. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-23. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- A. Mouton, Luwian Identities (2013) p. 335-40

- L. Cottrell, The Penguin Book of Lost Worlds 2 (1966) p. 158

- D. Ogden, A Companion to Greek Religion (2010) p. 151

- Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound (1982) p. 35

- A. Mouton, Luwian Identities (2013) p. 336

- H. Nettleship ed., A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1891) p. 86

- Ingersoll, Ernest (1923). Birds in legend fable and folklore. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 212–225.

- Mitchell, James (1908). Significant etymology. William Blackwood and Sons. pp. 16–17.

- Weekley, Ernest (1921). Etymological dictionary of modern English. London: John Murray. p. 90.

- Gen 44:5 LXX; cf. Gen 44:15 LXX

- cf. Deut 18:10, Lev 19:26 LXX

- L. R. Namier, The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III (London 1929) p. ii

- T. D'Elgin, The Everything Bird Book (1998) p. 225

Sources

- Baumbach, Manuel & Trampedach, Kai (2004). "'Winged Words': Poetry and Divination in Posidippus' Oiônoskopika.". In Acosta-Hughes, Benjamin; Kosmetatou, Elizabeth & Baumbach, Manuel (eds.). Labored in Papyrus Leaves: Perspectives on an Epigram Collection Attributed to Posidippus (P. Mil. Vogl. VIII 309). Hellenic Studies Series 2. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. ISBN 978-0-674-01105-2.

- Spence, Lewis, An Encyclopedia of Occultism, New York, Carl Publishing Group Edition, 1996. ISBN 0-8065-1401-9

- Mandelbaum, Allen, The Odyssey of Homer, New York, Bantam Classic Edition, 1991. ISBN 0-553-21399-7