Pagaruyung Kingdom

Pagaruyung (also Pagarruyung, Pagar Ruyung and, Malayapura or Malayupura)[2] was the seat of the Minangkabau kings of Western Sumatra,[3] though little is known about it. Modern Pagaruyung is a village in Tanjung Emas subdistrict, Tanah Datar regency, located near the town of Batusangkar, Indonesia.

Malayapura Pagaruyung | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1347–1833 | |||||||||

Marawa Minangkabau

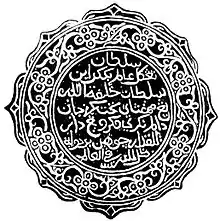

Royal seal[1]

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Pagaruyung, Sumatra | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit, Minang, and Melayu | ||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism (First Era), Animism, Sunni Islam (Last Era) | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Maharaja Diraja | |||||||||

• 1347–1375 (First King) | Adityawarman | ||||||||

• 1789–1833 Last King) | Sultan Tangkal Alam | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1347 | ||||||||

| 1833 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Indonesia |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

History

Beginnings

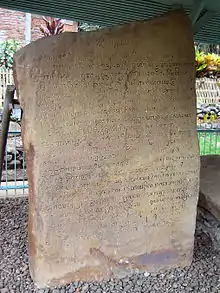

Adityawarman is believed to have founded the kingdom and presided over the central Sumatra region between 1347 and 1375,[4] most likely to control the local gold trade. The few artefacts recovered from Adityawarman's reign include a number of stones containing inscriptions, and statues. Some of these items were found at Bukit Gombak, a hill near modern Pagarruyung, and it is believed a royal palace was located there.

There is a major gap in the historical picture in the Minangkabau highlands between the last date of Adityawarman's inscription in 1375 and Tomé Pires Suma Oriental,[5] written some time between 1513 and 1515.

By the 16th century, the time of the next report after the reign of Adityawarman, royal power had been split into three recognised reigning kings. They were the King of the World (Raja Alam), the King of Adat (Raja Adat), and the King of Religion (Raja Ibadat). Collectively they were called the Kings of the Three Seats (Rajo Tigo Selo).

The first European to enter the region was Thomas Dias, a Portuguese employed by the Dutch governor of Malacca.[6] He travelled from the east coast to reach the region in 1684 and reported, probably from hearsay, that there was a palace at Pagaruyung and that visitors had to go through three gates to enter it.[7] The primary local occupations at the time were gold panning and agriculture, he reported.

Padri War

A civil war started in 1803 with the Padri fundamentalist Islamic group in conflict with the traditional syncretic groups, elite families and Pagarruyung royals. The original Pagaruyung Palace on Batu Patah Hill was burned down during a riot in Padri War back in 1804. During the conflict most of the Minangkabau royal family were killed in 1815, on the orders of Tuanku Lintau.

The British controlled the west coast of Sumatra between 1795 and 1819. Stamford Raffles visited Pagarruyung in 1818, reaching it from the west coast, and by then it had been burned to the ground three times. It was rebuilt after the first two fires, but abandoned after the third, and Raffles found little more than waringin trees.

The Dutch returned to Padang in May 1819. As a result of a treaty with a number of penghulu and representatives of the murdered Minangkabau royal family, Dutch forces made their first attack on a Padri village in April 1821.

The prestige of Pagaruyung remained high among the Minangkabau communities in the rantau, and when the members of the court were scattered following a failed rebellion against the Dutch in 1833, one of the princes was invited to become ruler in Kuantan.[8]

Influence

The influence of the kingdom of Pagaruyung covered almost the entire island of Sumatra as written by William Marsden in his book The history of Sumatra (1784). Several other kingdoms outside Sumatra also recognized Pagaruyung's sovereignty, although not in a tribute-giving relationship. There are as many as 62 to 75 small kingdoms in the archipelago which are the main ones in Pagaruyung, which are spread in the Philippines, Brunei, Thailand and Malaysia, as well as in Sumatra, East Nusa Tenggara and West Nusa Tenggara in Indonesia. The relationship is distinguished based on gradasi (gradations) of the relationship, namely sapiah balahan (female bloodline), kaduang karatan (male bloodline), Kapak radai, and timbang pacahan who are royal descendants.[9]

Notes

- Gallop 2002.

- Casparis 1975.

- Bosch 1931.

- Coedès 1968.

- Cortesão 1990.

- Ambler 1988.

- Colombijn 2005.

- Anon, (1893), Mededelingen...Kwantan. TBG 36: 325–42.

- "Pagaruyung, Simbol Perekat Nusantara". Kompas (in Indonesian). Retrieved 7 June 2020.

Sources

- Ambler, John S. (1988). "Historical Perspectives on Sawah Cultivation and the Political and Economic Context for Irrigation in West Sumatra" (PDF). Indonesia. 46 (46): 39–77. doi:10.2307/3351044. hdl:1813/53896. JSTOR 3351044.

- Bosch, Frederik David Kan (1930). De rijkssieraden van Pagar Roejoeng (in Dutch). Batavia: Oudheidkundig Verslag (Archaeological Report). pp. 49–108.

- de Casparis, J. G. (1975). Indonesian palaeography: a history of writing in Indonesia from the beginnings to c. AD 1500. Brill. ISBN 978-9004041721.

- Coedès, George (1968). Vella, Walter F. (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans. Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0824803681.

- Colombijn, Free (2005). "A Moving History of Middle Sumatra, 1600–1870" (PDF). Modern Asian Studies. 39 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1017/S0026749X04001374.

- Pires, Tomé (1990) [1513]. Cortesão, Armando (ed.). The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires. Laurie. ISBN 978-8120605350.

- Dobbin, Christine (1977). "Economic change in Minangkabau as a factor in the rise of the Padri movement, 1784–1830". Indonesia. 23 (1): 1–38. doi:10.2307/3350883. hdl:1813/53633. JSTOR 3350883.

- Drakard, Jane (1999). A Kingdom of Words: Language and Power in Sumatra. OUP. ISBN 978-983-56-0035-7.

- Gallop, Annabel Teh (2002). Malay seal inscriptions: a study in Islamic epigraphy from Southeast Asia. II. School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. p. 137. British Library, ILS catalogue number: 12454119.

- Jakarta Post (1 March 2007). "West Sumatra palace destroyed by fire". Syofiardi Bachyul. Padang: The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- Jakarta Post (23 November 2013). "Istano Basa Pagaruyung: Restored to glory". Syofiardi Bachyul. The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013.

- Kompas (28 February 2007). "Perbaikan Istana Pagaruyung Lebih dari Rp 20 Miliar" (in Indonesian). Mahdi Muhammad. Tanah Datar: Kompas. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007.

- Miksic, John (2004). "From megaliths to tombstones: the transition from pre-history to early Islamic period in highland West Sumatra". Indonesia and the Malay World. 32 (93): 191–210. doi:10.1080/1363981042000320134.

- Tempo (28 February 2007). "Kebakaran Istano Basa Isyarat Kepada Pemerintah" (in Indonesian). Padang: Tempo Interaktif. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.