French and British interregnum in the Dutch East Indies

French and British interregnum in the Dutch East Indies were a relatively short period of French and followed by British interregnum on the Dutch East Indies that took place between 1806 and 1815. The French ruled between 1806 and 1811. The British took over for 1811 to 1815, and transferred its control back to the Dutch in 1815.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Indonesia |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The fall of the Netherlands to the French Empire and the dissolution of the Dutch East India Company led to some profound changes in the European colonial administration of the East Indies, as one of the Napoleonic Wars was fought in Java.[1] This period, which lasted for almost a decade, witnessed a tremendous change in Java, as vigorous infrastructure and defence projects took place, followed by battles, reformation and major changes of administration in the colony.

Prelude

In 1800, Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC)) was declared bankrupt and nationalised by the Dutch government. As a result, its assets, which included seaports, storehouses, fortifications, settlements, lands and plantations in the East Indies were nationalised as a Dutch colony, the Dutch East Indies. Based in Batavia (today Jakarta), the Dutch ruled most of Java (with exception of interior lands of Vorstenlanden Mataram and Banten), conquering coastal West Sumatra, wrestled former Portuguese colonies in Malacca, the Moluccas, South and North Celebes also in West Timor. Among these Dutch possessions, Java was the most important one, as the production of cash-crops and Dutch-controlled plantations was located there.

On the other side on the world, Europe was devastated by the Napoleonic Wars. A conquest and revolution were shifting the politics, relations and dynamics among the European empires and nations, which affected their colonies in the Far East. The Netherlands under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806, oversaw the Batavian Republic become the Commonwealth of Batavia and then dissolved and replaced by the Kingdom of Holland, a French puppet kingdom ruled by Napoleon's third brother Louis Bonaparte (Lodewijk Napoleon). As a result, the East Indies during this time were treated as a proxy French colony, administrated through Dutch intermediary.

The power struggle and rivalry between France and Britain had spilled to other parts of the world, involving the colonies of each empires in Americas, Africa, as well as in Asia. Since 1685 the British had consolidated their rule in Bencoolen on western coast of Sumatra, and also had established their rule in Malaccan strait, the island of Singapore and Penang. As the British coveted the Dutch colonies in the region, the Dutch-controlled East Indies was bracing for the predicted incoming British invasion.

French interregnum 1806–1811

In 1806, King Lodewijk Napoleon of the Netherlands sent one of his general, Herman Willem Daendels, serving as governor-general of East Indies based in Java. Daendels was sent to strengthen Javanese defences against a perceived incoming British invasion. He arrived in the city of Batavia (now Jakarta) on 5 January 1808 and relieved the former Governor General, Albertus Wiese. He raised new forces, built new roads within Java, and improved the internal administration of the island.[1]

Daendels' rule was a harsh and martial one, as the colony prepared for the British threat. He built new hospitals and military barracks, a new arms factories in Surabaya and Semarang, and a new military college in Batavia. He demolished the Castle in Batavia and replaced it with a new fort at Meester Cornelis (Jatinegara), and built Fort Lodewijk in Surabaya. However, his best-known achievement was the construction of the Great Post Road (Indonesian: Jalan Raya Pos) across northern Java from Anjer to Panaroecan. The road now serves as the main road in the island of Java, called Jalur Pantura. The thousand-kilometre road was completed in only one year, during which thousands of Javanese forced labourers died.[2]

The reign of Catholic King Lodewijk in the Netherlands ended the centuries-old of religious discriminations against Catholics both in the Netherlands and in the East Indies. Previously the Netherlands only favoured Protestantism. The Catholics were permitted freedom of worship in the Dutch Indies, though this measure was mainly intended for European Catholics, since Daendels ruled under the authority of Napoleonic France. This religious freedom would be consolidated later by Thomas Raffles.

Daendels — known as an avid Francophile — built a new governor general palace in smaller version Château de Versailles-style in Batavia, known as Daendels' Palace or Witte Huis (White House) is often referred to Groote Huis (Big House). It is now Indonesia's Ministry of Finance office on the east side of Lapangan Banteng (Waterlooplein). He also renamed Buffelsveld (buffalo field) to Champs de Mars (today Merdeka Square). Daendels' rule oversaw the complete adoption of Continental Law into the colonial Dutch East Indies law system, retained even until today in Indonesian legal system. Indonesian law is often described as a member of the 'civil law' or 'Continental' group of legal systems found in European countries such as France and the Netherlands.[3]

Daendels displayed a firm attitude towards the local Javanese rulers, with the result that the rulers later were willing to work with the British against the Dutch. He also subjected the population of Java to forced labour (Rodi). There were some rebellious actions against this, such as those in Cadas Pangeran, West Java. He was also responsible for the dissolution of Banten Sultanate. In 1808, Daendels ordered Sultan Aliyuddin II of Banten to move the Sultanate capital to Anyer and to provide labour to build a new port planned to be built at Ujung Kulon. The Sultan refused Daendels' command, and in response Daendels ordered the invasion of Banten and destruction of Surosowan palace. The Sultan, together with his family, was arrested in Puri Intan and held as a prisoner in Fort Speelwijk, and later sent into exile in Ambon. On 22 November 1808, Daendels declared from his headquarters in Serang that the Sultanate of Banten had been absorbed into the territory of the Dutch East Indies.[4]

British interregnum 1811–1815

In the middle of 1809 the Colonial Governor of India, the 1st Earl of Minto wanted to conquer the lucrative Spice islands. For the East India Company the occupation of these islands meant not only a curtailment of Dutch and French trade and power in the East Indies but also an equivalent gain to the company of the rich trade in spice. In addition the conquest of these islands meant that they would be a good base from which to conquer Java. In 1810 the most heavily defended islands Banda Neira, Ambon and Ternate fell, and by August the region had been conquered with little loss.

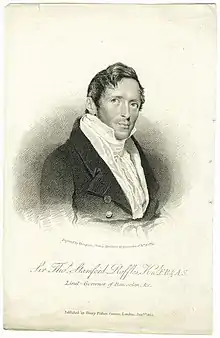

In 1811, Java fell to a British force force under Minto. He appointed Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles as lieutenant governor of Java. Raffles carried further the administrative centralisation previously initiated by Daendels. He planned to group the regencies of Java into 16 residencies. He ended Dutch administrative methods, liberalised the system of land tenure, and extended trade. Raffles tried to implement the liberal economic principles and the cessation of compulsory cultivation in Java.

Raffles took his residence at Buitenzorg and despite having a small subset of Britons as his senior staff, he kept many of the Dutch civil servants in the governmental structure. He also negotiated peace and mounted several military expeditions against local Javanese princes. The most significant of these was 21 June 1812 assault on Yogyakarta, one of the two most powerful indigenous polities in Java. During the attack the Yogyakarta kraton was badly damaged and sacked, with Raffles seizing much of the contents of the court archive. The event was unprecedented in Javanese history, as it was the first time an indigenous court had been captured by a European army, resulting in the humiliation of the local aristocracy.[5][6] Raffles also ordered an expedition to Palembang in Sumatra to depose the local sultan, Mahmud Badaruddin II, and to seize the nearby Bangka Island to set up a permanent British presence in the area.[7] Other than Javanese court archives, Raffles also sent a number of Javanese archaeological artefacts, such as a Buddha head from Borobudur and two large ancient Javanese stone inscriptions, known today as the Minto Stone and the Calcutta Stone to Lord Minto as a token of appreciation.[8][9]

Raffles particularly holds special interest on the history, culture and the people of Java. During his short reign, British Java saw the surge of archaeological surveys and government attention on local culture, art and history. His administration rediscovered the ruins of the great Buddhist mandala of Borobudur in Central Java. Other archaeological sites in Java such as Prambanan Hindu temple and ancient Majapahit city of Trowulan, also came to light during his administration. Under Raffles patronage, a large number of ancient monuments in Java were rediscovered, excavated and systematically catalogued for the first time. Raffles was the enthusiast of the island's history, as he wrote the book History of Java published later in 1817.[10]

In 1815, the island of Java was returned to control of the Netherlands following the end of Napoleonic Wars, under the terms of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814. In 1816, the Dutch regained the full control of their colony in Java and other parts of the archipelago, and they would embark on their conquest over other independent polities in the archipelago. By 1920 they had consolidated their realm, a colonial state in the Indonesian archipelago, established Dutch East Indies as one of the most profitable European colony in the world's colonial history.

References

- Asvi Warman Adam. "The French and the British in Java, 1806–15". Britannica.

- Pramoedya sheds light on dark side of Daendels' highway. The Jakarta Post 8 January 2006.

- Timothy Lindsey, ed. (2008). Indonesia, Law and Society. Federation Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781862876606. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Ekspedisi Anjer-Panaroekan, Laporan Jurnalistik Kompas. Penerbit Buku Kompas, PT Kompas Media Nusantara, Jakarta Indonesia. November 2008. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-979-709-391-4.

- Ricklefs, M. C. A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1200, 4th Edition, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008

- Carey, Peter, The Power of Prophecy: Prince Dipanagara and the End of an Old Order in Java, 1785-1855, 2008

- Abdullah, Husnial Husin (1983). Sejarah Perjuangan Kemerdekaan R.I. Di Bangka Belitung. Karya Unipress. p. 393.

- Noltie, Henry (2009). Raffles' Ark Redrawn: Natural History Drawings from the Collection of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. London & Edinburgh: British Library & Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. pp. 19–20.

- Kern, H., (1917), Steen van den berg Pananggungan (Soerabaja), thans in’t India Museum te Calcutta, Verspreide Gescriften VII, 85-114, Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Carey, Peter, The Power of Prophecy: Prince Dipanagara and the End of an Old Order in Java, 1785-1855, 2008