Prehistoric Indonesia

Prehistoric Indonesia is a prehistoric period in the Indonesian archipelago that spanned from the Pleistocene period to about the 4th century CE when the Kutai people produced the earliest known stone inscriptions in Indonesia.[1] Unlike the clear distinction between prehistoric and historical periods in Europe and the Middle East, the division is muddled in Indonesia. This is mostly because Indonesia's geographical conditions as a vast archipelago caused some parts — especially the interiors of distant islands — to be virtually isolated from the rest of the world. West Java and coastal Eastern Borneo, for example, began their historical periods in the early 4th century, but megalithic culture still flourished and script was unknown in the rest of Indonesia, including in Nias, Batak, and Toraja. The Papuans on the Indonesian part of New Guinea island lived virtually in the Stone Age until their first contacts with modern world in the early 20th century. Even today living megalithic traditions still can be found on the island of Sumba and Nias.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Indonesia |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Geology

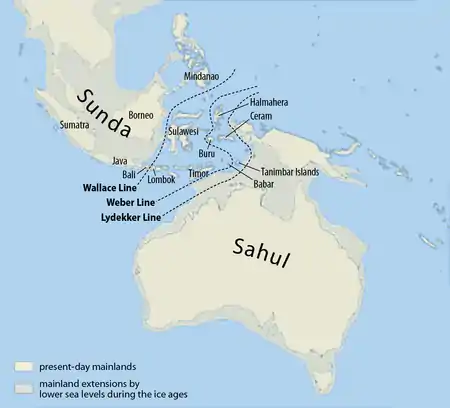

Geologically, the area of modern Indonesia appeared from under the Southeast Asian seas as the result of the Indian and Australian plates colliding and slipping under the Sunda Plate, sometime in the early Cenozoic era around 63 million years ago.[2] This tectonic collision created Sunda volcanic Arc that has produced chains of islands of Sumatra, Java and the Lesser Sunda Islands. The active volcanic arc creating supervolcano that today become Lake Toba in Sumatra. The massive eruption of Toba supervolcano that occurred some time between 69,000 and 77,000 years ago (72,000 BC) instigated the Toba catastrophe theory, a global volcanic winter that caused a bottleneck in human evolution. Other notable volcanoes in Sunda Arc are Mount Tambora (erupted in 1815) and Krakatau (erupted in 1883). The region is known for its instability due to volcano formations and other volcanic and tectonic activities as well as climate changes; resulted in lowlands drowned occasionally under shallow seas, the formation of islands, the connection and disconnection of islands through narrow land-bridges, etc.

The Indonesian archipelago nearly reached its present form in the Pleistocene period. For some periods, the Sundaland was still linked with Asian mainland, creating the landmass extension of Southeast Asia that enabled the migrations of some Asian animals and hominid species. Geologically the New Guinea island and the shallow seas of Arafura is the northern part of Australia tectonic plate and once connected as a land bridge identified as Sahulland. During the end of the last ice age (around 20,000–10,000 years ago), earth experienced global climate change; a global warming with the rising of average temperature caused the melting of polar ice caps and contributed to the rising of sea surface. Sundaland was submerged under shallow sea, creating Malacca Strait, South China Sea, Karimata Strait and Java Sea. During that period, Malay peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Borneo and the islands around them were formed. On the east, New Guinea and Aru Islands were separated from the Australia mainland. The rise of sea surface created isolated areas that separated plants, animals and hominid species, causing further evolution and specification.

Human migration

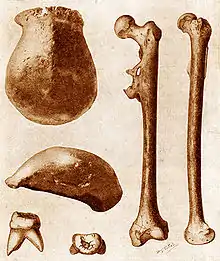

Homo erectus

In 2007 analysis of cut marks on two bovid bones found in Sangiran, showed them to have been made 1.5 to 1.6 million years ago by clamshell tools, and is the oldest evidence for the presence of early man in Indonesia. Fossilised remains of Homo erectus, popularly known as the "Java Man" were first discovered by the Dutch anatomist Eugène Dubois at Trinil in 1891, and are at least 700,000 years old, at that time the oldest human ancestor ever found. Further Homo erectus fossils of a similar age were found at Sangiran in the 1930s by the anthropologist Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald, who in the same time period also uncovered fossils at Ngandong alongside more advanced tools, re-dated in 2011 to between 550,000 and 143,000 years old.[3][4] In 1977 another Homo erectus skull was discovered at Sambungmacan.[5]

Homo floresiensis

In 2003, on the island of Flores, fossils of a new small hominid dated between 74,000 and 13,000 years old and named "Flores Man" (Homo floresiensis) were discovered much to the surprise of the scientific community.[6] This 3 foot tall hominid is thought to be a species descended from Homo Erectus and reduced in size over thousands of years by a well known process called island dwarfism. Homo floresiensis was first dated to relatively recent time periods - as recent as 14,000 years ago,[7] however re-examination of the sediments has revised these dates and these hominins have been shown to have been present in Indonesia since at least 700,000 years ago, until about 60-50,000 years ago.[8] In 2010 stone tools were discovered on Flores dating from 1 million years ago, which is the oldest evidence anywhere in the world that early man had the technology to make sea crossings at this very early time.[9]

Homo sapiens

The archipelago was formed during the thaw after the latest ice age. Early humans travelled by sea and spread from mainland Asia eastward to New Guinea and Australia. Homo sapiens reached the region by around 45,000 years ago.[10] In 2011 evidence was uncovered in neighbouring East Timor, showing that 42,000 years ago these early settlers had high-level maritime skills, and by implication the technology needed to make ocean crossings to reach Australia and other islands, as they were catching and consuming large numbers of big deep-sea fish such as tuna.[11]

Earliest migration

Early Homo sapiens reached the archipelago between 60,000 and 45,000 years ago. Many but not all[12] Southeast Asian Homo sapiens fossils prior to about 8,000 BCE have been identified as being distinct from Austronesians.[13] The remnants of the pre-Austronesian groups of Southeast Asia survive in isolated pockets in Malaysia (Semang) and the Philippines (Aeta). The descendants of the pre-Austronesian inhabitants of the Indonesian Archipelago are still the majority in the eastern portion of the region, in islands such as New Guinea, the Maluku and East Nusa Tenggara. Genetic studies show that in Western Papua there was significant genetic admixture between Negritos, Australo-Melanesians and Austronesians.[14]

Rock art

Approximately 40,000 years ago, early humans produced prehistoric rock art motifs in volcanic caves on the island of Sulawesi. This means that humans at both extremes of the Pleistocene Eurasian world, Europe and Indonesia, were producing rock art during the same time period.[15] The most notable rock art sites in Indonesia are the Maros-Pangkep rock art sites at the caves in South Sulawesi province. There are two distinct styles of art within these caves, both dated to the Pleistocene period. The first consists of human hand stencils, made by spraying wet pigment spit from the mouth, around human hands that were pressed against the cave wall surfaces. The second is a less common style of cave art, characterized by images drawn of larger, naturalistic profile paintings of wild land mammals that were endemic to the island during the Pleistocene period, such as miniature buffalos and warty pigs.[16]

Other than Altamira, the Maros cave art is one of the most extensive sites of cave rock art in the world. These Indonesian prehistoric cave paintings might be the oldest cave art in the world. This find has challenged the established interpretation that Europe was the birthplace of prehistoric rock art.[17]

In 11 December 2019, a team of researchers led by Dr. Maxime Aubert announced the discovery of the oldest hunting scenes in prehistoric art in the world which is more than 44,000 years old from the limestone cave of Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4. Archaeologists determined the age of the depiction of hunting a pig and buffalo thanks to the calcite ‘popcorn’, different isotope levels of radioactive uranium and thorium.[18][19][20][21]

In 16 March 2020, a team of archaeologists led by Griffith University has uncovered the first known examples of ‘portable art’, which are probably 14,000 - 26,000 years old, from a limestone cave named Leang Bulu Bettue in Sulawesi and published in the academic journal Nature Human Behaviour. While one of the stones contained an anoa (water buffalo) and what may be a flower, star or eye, another depicted an astronomic rays of light.[22][23][24]

In January 2021, archaeologists announced the discovery of at least 45,500 years old cave art in Leang Tedongnge cave. According to the journal Science Advances, cave painting of warty pig is the earliest evidence of human settlement of the region. Adult male pig, measuring 136 cm x 54 cm, was depicted with horn-like facial warts and two hand prints above its hindquarters. According to co-author Adam Brumm, there are two other pigs that are partly preserved and it appears, the wart pig was observing a fight between two of them.[25][26][27][28]

Prehistoric jewelry

Ornaments made from bones and teeth of babirusa deer-pig and bear cuscuses (Ailurops ursinus) marsupial, was unearthed from limestone caves in Sulawesi. These jewellery was ingeniously manufactured from the teeth of the primitive pigs and bones of marsupials, estimated dated to between 22,000 and 30,000 years ago.[29]

Austroasiatic migration and admixture

Negritos and Australo-Melanesians dominated most of the Indonesian archipelago until 6,300 years ago, when two massive human migrations from Indochina swayed the demographics of the archipelago.[12] Scientists suggest that there were two major migratory flows into the archipelago that were ancestral to modern Indonesians. First, Austroasiatic speakers arrived around 6,300-5,000 years ago, and then, Austronesian speakers arrived around 4,000 years ago.[13][12][30]

The Austroasiatic and Austronesian languages may have originally come from a larger common language family, the Austric languages. The language may have been spoken by Yunnan people of Southern China before breaking into the two previously mentioned language families.[13] However, this is a controversial hypothesis that not all linguists agree with.

Austroasiatic people spread via Indochina, from Yunnan in Southern China to Vietnam and Cambodia, then to the Malay Peninsula before finally arriving in Sumatra, Borneo and Java. Genetic studies show that Javanese, Sundanese and Balinese people have significant proportion of Austroasiatic ancestry.[31]

Genome studies show that several ethnic groups in western Indonesian archipelago have significant Austroasiatic genome markers, despite none of these groups speaking Austroasiatic languages. Thus this could mean, that there was either once a substantial Austroasiatic presence in Island Southeast Asia, or Austronesian speakers migrated to and through the mainland. The substantial presence of Austroasiatic ancestry in western Indonesian archipelago suggests that the western branch of Austroasiatic migration from Indochina might have taken place in pre-Neolithic era. The contesting suggestion argues for Austroasiatic-Austronesian admixture — which probably took place in the Malaysian peninsula or southern Vietnam, intermixing there before continuing to western Indonesia.[14]

Austronesian migration and expansion

Austronesian speakers came to Indonesian archipelago circa 4,000 years ago.[13] Both Austroasiatic and Austronesian branched from Southern China. However, unlike Austroasiatic people that spread south through the continent, the Austronesian group developed in Taiwan and spread by island hopping throughout the region.

Austronesian expansion began 4,000–5,000 years ago, and likely had its roots in Taiwan.[14] The sea-faring Austronesian people sailed through the region and performed island-hopping — from Taiwan south through the Philippines Archipelago - and reached the central Indonesian archipelago. From there they expanded to western Indonesia and eastern Indonesia, where they met earlier inhabitant Australoid people. In addition, the western branch arrived in Borneo, Java and Sumatra where it met the Austroasiatic migrants, in addition to the existing Australoid population.[13]

Austronesian soon become the dominant group replacing the Australoid population, that today remains significantly only in the Eastern region. On the other hand, Austronesian successfully influenced the Austroasiatic speakers, so finally all of the population in the Western Indonesian archipelago became Austronesian speakers,[13] despite some ethnic groups (Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese) showing significant Austroasiatic genetic markers. Genome studies discovered that the inhabitants of central and eastern Indonesian archipelago have a significant Austronesian ancestry.[14]

Around 2,000 BCE there was an expansion of seafaring Austronesians from Asia, who spread throughout Maritime Southeast Asia all the way to Oceania and in later period reached Madagascar. Austronesian people form the majority of the modern population of Indonesia.[32]

Chronology

Paleolithic

Homo erectus were known to utilise simple coarse paleolithic stone tools and also shell tools, discovered in Sangiran and Ngandong. Cut mark analysis of Pleistocene mammalian fossils documents 18 cut marks inflicted by tools of thick clamshell flakes on two bovid bones created during butchery at the Pucangan Formation in Sangiran between 1.6 and 1.5 million years ago. These cut marks document the use of the first tools in Sangiran and the oldest evidence of shell tool use in the world.[33]

Neolithic

The polished stone tools of Neolithic culture, such as polished stone axes and stone hoes, were developed by the Austronesian people in the Indonesian archipelago. Also during the Neolithic period, large stone structures of the megalithic culture flourished in archipelago.

Megalithic

The Indonesian archipelago is the host of Austronesian megalith cultures both past and present. Several megalith sites and structures are also found across Indonesia. Menhirs, dolmens, stone tables, ancestral stone statues, and step pyramid structure called Punden Berundak were discovered in various sites in Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and the Lesser Sunda Islands.

Punden step pyramid and menhir can be found in Pagguyangan Cisolok and Gunung Padang, West Java. Cipari megalith site also in West Java displayed monolith, stone terraces, and sarcophagus.[34] The Punden step pyramid is believed to be the predecessor and basic design of later Hindu-Buddhist temples structure in Java after the adoption of Hinduism and Buddhism by the native population. The 8th century Borobudur and 15th-century Candi Sukuh featured the step-pyramid structure.

Lore Lindu National Park in Central Sulawesi houses ancient megalith relics such as ancestral stone statues. Mostly located in the Bada, Besoa and Napu valleys.[35]

Living megalith cultures can be found on Nias, an isolated island off the western coast of North Sumatra, the Batak people in the interior of North Sumatra, on Sumba island in East Nusa Tenggara and also Toraja people from the interior of South Sulawesi. These megalith cultures remained preserved, isolated and undisturbed well into the late 19th century.

Bronze Age

Dong Son culture spread to Indonesia bringing with it techniques of bronze casting, wet-field rice cultivation, ritual buffalo sacrifice, megalithic practises, and ikat weaving methods. Some of these practices remain in areas including the Batak areas of Sumatra, Toraja in Sulawesi, and several islands in Nusa Tenggara. The artefacts from this period are Nekara bronze drums discovered throughout Indonesian archipelago, and also ceremonial bronze axe.

Belief system

Early Indonesians were animists who honoured the spirits of nature as well as the ancestral spirits of the dead, as they believed their souls or life force could still help the living. The reverence for ancestral spirits is still widespread among Indonesian native ethnicities; such as among Nias people, Batak, Dayak, Toraja, and Papuans. These reverence among others are evident through the harvest festivals that often invoked the nature spirits and agriculture deities, to the elaborate burial rituals and processions of the deceased elders to preparing and sending them to the realm of ancestors. The prehistoric spirit of ancestors or nature that possess supernatural abilities is identified as hyang in Java and Bali, and still revered in Balinese Hinduism.

Way of life

The human livelihood of prehistoric Indonesia ranges from simple forest hunter-gatherer equipped with stone tools to elaborated agriculture society with grain cultivation, domesticated animals, with weaving and pottery industry.

Ideal agricultural conditions, and the mastering of wet-field rice cultivation as early as the 8th century BCE,[36] allowed villages, towns, and small kingdoms to flourish by the 1st century CE. These kingdoms (little more than collections of villages subservient to petty chieftains) evolved with their own ethnic and tribal religions. Java's hot and even temperature, abundant rain and volcanic soil, was perfect for wet rice cultivation. Such agriculture required a well-organised society in contrast to dry-field rice, which is a much simpler form of cultivation that doesn't require an elaborate social structure to support it.

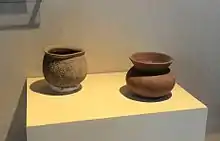

Buni culture clay pottery was flourished in coastal northern West Java and Banten around 400 BCE to 100 CE [37] Buni culture was probably the predecessor of Tarumanagara kingdom, one of the earliest Hindu kingdom in Indonesia that produces numerous inscriptions, marked the beginning of historical period in Java.

List of sites

Prehistoric relics, such as bones of prehistoric animals and hominids, megalithic monolith such as menhirs, dolmens, statues, burial sites, and paintings in caves cliff niches, include the following:

- Putri cave, Baturaja, South Sumatra

- Pasemah prehistoric site, Lampung

- Caves of Sangkulirang Hill, East Kutai Regency, East Kalimantan

- Cibedug prehistoric site, Banten

- Pangguyangan megalithic sites, Cisolok, Sukabumi Regency, West Java

- Cipari megalithic site, Kuningan, West Java

- Pawon caves, Bandung Regency, West Java

- Gunung Padang Megalithic Site, Cianjur Regency, West Java

- Gunung Padang site, Cilacap Regency, Central Java

- Sangiran valley, Central Java

- Wajak prehistoric sites, Tulungagung Regency, East Java

- Mbolu village prehistoric site, Ngepo village, Tanggunggunung subdistric, Tulungagung Regency, East Java

- Gilimanuk prehistoric site, Jembrana Regency, Bali

- Keramas village prehistoric site, Blahbatuh subdistric, Gianyar regency, Bali

- Leang-leang caves, Maros Regency, South Sulawesi

- Megalithic statues of Lore Lindu National Park, Central Sulawesi

- Liang Bua, Flores, East Nusa Tenggara

- Biak caves prehistoric sites, Biak, Papua (40.000-30.000 SM)[38]

- Beach side prehistoric painting site, Raja Ampat, West Papua

- Tutari megalithic sites, Jayapura, Papua[38]

- Babi caves, Mount Batu Buli, Randu village, Muara Uya, Tabalong, South Kalimantan

See also

Notes

- S. Supomo (1995). "Indic Transformation: The Sanskritization of Jawa and the Javanization of the Bharata". In Peter Bellwood; James J. Fox; Darrell Tryon (eds.). The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Canberra: Australian National University. pp. 309–332.

- MacKinnon, Kathy (1986). Alam Asli Indonesia. Jakarta: Penerbit PT Gramedia. p. 8.

- "Finding showing human ancestor older than previously thought offers new insights into evolution".

- Pope, G G (1988). "Recent advances in far eastern paleoanthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 17 (1): 43–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.17.100188.000355. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. pp. 309–312.; Pope, G (15 August 1983). "Evidence on the Age of the Asian Hominidae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (16): 4988–4992. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.16.4988. PMC 384173. PMID 6410399. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 309.; de Vos, J.P.; P.Y. Sondaar (9 December 1994). "Dating hominid sites in Indonesia" (PDF). Science Magazine. 266 (16): 4988–4992. doi:10.1126/science.7992059. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 309.

- Delson, Eric; Harvati, Katerina; Reddy, David; Marcus, Leslie F.; Mowbray, Kenneth; Sawyer, G. J.; Jacob, Teuku; Márquez, Samuel (1 April 2001). "The Sambungmacan 3 Homo erectus calvaria: A comparative morphometric and morphological analysis: Sambungmacan 3 Homo Erectus Analysis" (PDF). The Anatomical Record. 262 (4): 380–397. doi:10.1002/ar.1048. PMID 11275970. S2CID 25438682.

- Brown, P.; Sutikna, T.; Morwood, M. J.; Soejono, R. P.; Jatmiko; Wayhu Saptomo, E.; Rokus Awe Due (27 October 2004). "A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia". Nature. 431 (7012): 1055–1061. doi:10.1038/nature02999. PMID 15514638. S2CID 26441.; Morwood, M. J.; Soejono, R. P.; Roberts, R. G.; Sutikna, T.; Turney, C. S. M.; Westaway, K. E.; Rink, W. J.; Zhao, J.- X.; van den Bergh, G. D.; Rokus Awe Due; Hobbs, D. R.; Moore, M. W.; Bird, M. I.; Fifield, L. K. (27 October 2004). "Archaeology and age of a new hominin from Flores in eastern Indonesia". Nature. 431 (7012): 1087–1091. doi:10.1038/nature02956. PMID 15510146. S2CID 4358548.

- Morwood, M.; Soejono, R. P.; Roberts, R. G.; Sutikna, T.; Turney, C. S. M.; Westaway, K. E.; Rink, W. J.; Zhao, J.- X.; van den Bergh, G. D.; Rokus Awe Due; Hobbs, D. R.; Moore, M. W.; Bird, M. I.; Fifield, L. K. (27 October 2004). "Archaeology and age of a new hominin from Flores in eastern Indonesia". Nature. 431 (7012): 1087–1091. doi:10.1038/nature02956. PMID 15510146. S2CID 4358548.

- Sutikna, T.; Tocheri, M.W.; Morwood, M.J.; E. W. Saptomo; Jatmiko; R. Due Awe; S. Wasisto; K. E. Westaway; M. Aubert; B. Li; J-x. Zhao; M. Storey; B. V. Alloway; M. W. Morley; H. J. M. Meijer; G. D. van den Bergh; R. Grün; A. Dosseto; A. Brumm; W. L. Jungers; R. G. Roberts (21 April 2016). "Revised Stratigraphy and Chronology for Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua in Indonesia". Nature. 532 (7599): 366–369. doi:10.1038/nature17179. PMID 27027286. S2CID 4469009.

- Savage, Sam (18 March 2010). "Flores Man Could Be 1 Million Years Old". RedOrbit. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Smithsonian (July 2008). "The Great Human Migration": 2. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Evidence of 42,000 year old deep sea fishing revealed". Past Horizons. 26 November 2011. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576077702.

- "Dua Arus Besar Migrasi Leluhur ke Nusantara". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). 7 August 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Mark Lipson; Po-Ru Loh; Nick Patterson; Priya Moorjani; Ying-Chin Ko; Mark Stoneking; Bonnie (2014). "Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia". Nature. 5: 4689. doi:10.1038/ncomms5689. PMC 4143916. PMID 25137359.

- Matthew MacEgan (7 November 2014). "Prehistoric rock art in Indonesia dated to 40,000 years ago". World Socialist Website.

- Jeanna Bryner (8 October 2014). "In Photos: The World's Oldest Cave Art". Live Science.

- Megan Gannon (8 October 2014). "Prehistoric Paintings in Indonesia May Be Oldest Cave Art Ever". Live Science.

- "Animal painting found in cave is 44,000 years old". BBC News. 12 December 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Narrative Cave Art in Indonesia Dated to 44,000 Years Ago | ARCHAEOLOGY WORLD". Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- correspondent, Hannah Devlin Science (11 December 2019). "Earliest known cave art by modern humans found in Indonesia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Guarino, Ben (12 December 2019). "The oldest story ever told is painted on this cave wall, archaeologists report". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- "Two 20,000-Year-Old Artworks From Indonesia Prove That Europe Wasn't the Only Place Art Was Being Made During the Last Ice Age". artnet News. 26 March 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Rosengreen, Carley. "Portable rock art 'social glue' for early humans in Ice Age". news.griffith.edu.au. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Wu, Katherine J. "Portable, Pocket-Sized Rock Art Discovered in Ice Age Indonesian Cave". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Brumm, Adam; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Burhan, Basran; Hakim, Budianto; Lebe, Rustan; Zhao, Jian-xin; Sulistyarto, Priyatno Hadi; Ririmasse, Marlon; Adhityatama, Shinatria; Sumantri, Iwan; Aubert, Maxime (1 January 2021). "Oldest cave art found in Sulawesi". Science Advances. 7 (3): eabd4648. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd4648. ISSN 2375-2548.

- France-Presse, Agence (13 January 2021). "World's oldest known cave painting found in Indonesia". the Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "Indonesia: Archaeologists find world's oldest animal cave painting". BBC News. 14 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Post, The Jakarta. "World's oldest known cave painting found in South Sulawesi". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Jewel Topsfield; Karuni Rompies (5 April 2017). "Prehistoric jewellery found in Indonesian cave challenges view early humans less advanced". Sydney Morning Herald.

- "Karl Anderbeck, "Suku Batin - A Proto-Malay People? Evidence from Historical Linguistics", The Sixth International Symposium on Malay/Indonesian Linguistics, 3 - 5 August 2002, [[Bintan Island]], [[Riau]], Indonesia". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Pemetaan Genetika Manusia Indonesia". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Taylor (2003), pages 5–7

- Choi, Kildo; Driwantoro, Dubel (January 2007). "Shell tool use by early members of Homo erectus in Sangiran, central Java, Indonesia: cut mark evidence". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (1): 48–58. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.03.013.

- |Cipari archaeological park discloses prehistoric life in West Java.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)|Lore Lindu National Park, Central Sulawesi.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- Zahorka, Herwig (2007). The Sunda Kingdoms of West Java, From Tarumanagara to Pakuan Pajajaran with Royal Center of Bogor, Over 1000 Years of Propsperity and Glory. Yayasan cipta Loka Caraka.

- "Papua Kaya Situs Arkeologi Kuno". Kompas. 17 April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009.

- Moore, MW; Brumm (2007). "Stone artifacts and hominins in island Southeast Asia: New insights from Flores, eastern Indonesia". Journal of Human Evolution. 52 (1): 85–102. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.002. PMID 17069874.