Polyandry

Polyandry (/ˈpɒliˌændri, ˌpɒliˈæn-/; from Greek: πολυ- poly-, "many" and ἀνήρ anēr, "man") is a form of polygamy in which a woman takes two or more husbands at the same time. Polyandry is contrasted with polygyny, involving one male and two or more females. If a marriage involves a plural number of "husbands and wives" participants of each gender, then it can be called polygamy,[1] group or conjoint marriage.[2] In its broadest use, polyandry refers to sexual relations with multiple males within or without marriage.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Anthropology of kinship |

|---|

|

|

Social anthropology Cultural anthropology |

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

Of the 1,231 societies listed in the 1980 Ethnographic Atlas, 186 were found to be monogamous; 453 had occasional polygyny; 588 had more frequent polygyny; and 4 had polyandry.[3] Polyandry is less rare than this figure suggests, as it considered only those examples found in the Himalayan mountains (28 societies). More recent studies have found more than 50 other societies practicing polyandry.[4]

Fraternal polyandry is practiced among Tibetans in Nepal and parts of China, in which two or more brothers are married to the same wife, with the wife having equal "sexual access" to them.[5][6] It is associated with partible paternity, the cultural belief that a child can have more than one father.[4]. Several ethnic groups practicing polyandry in India identify their customs with their descent from Draupadi, a central character of the Mahabharta who was married to five brothers, although local practices may not be fraternal themselves.

Polyandry is believed to be more likely in societies with scarce environmental resources. It is believed to limit human population growth and enhance child survival.[6][7] It is a rare form of marriage that exists not only among peasant families but also among the elite families.[8] For example, polyandry in the Himalayan mountains is related to the scarcity of land. The marriage of all brothers in a family to the same wife allows family land to remain intact and undivided. If every brother married separately and had children, family land would be split into unsustainable small plots. In contrast, very poor persons not owning land were less likely to practice polyandry in Buddhist Ladakh and Zanskar.[6] In Europe, the splitting up of land was prevented through the social practice of impartible inheritance. With most siblings disinherited, many of them became celibate monks and priests.[9]

Polyandrous mating systems are also a common phenomenon in the animal kingdom.

Types

Successional Polyandry

Unlike fraternal polyandry where a woman will receive a number of husbands simultaneously, a woman will acquire one husband after another in sequence.

This form is flexible. These men may or may not be related. And it may or may not incorporate a hierarchical system, where one husband is considered primary and may be allotted certain rights or privileges not awarded to secondary husbands, such as biologically fathering a child.

In this particular system, the secondary husbands have the power to succeed the primary if he were to become severely ill or be away from the home for a long period of time or is otherwise rendered incapable of fulfilling his husbandly duties.

Successional polyandry can likewise be egalitarian, where all husbands are equal in status and receive the same rights and privileges. In this system, each husband will have a wedding ceremony and share paternity of whatever children she may bear.

Other Classifications: Secondary

Associated Polyandry

Another form of polyandry is a combination of polyandry and polygyny, as women are married to several men simultaneously and the same men are married to several women. It is found in some tribes of native Africa as well as villages in northern Nigeria and the northern cameroons.

Other Classifications: Equal polygamy, Polygynandry

The system results in less land fragmentation, and a diversification of domestic activities.

Fraternal polyandry

Fraternal polyandry (from the Latin frater—brother), also called adelphic polyandry (from the Greek ἀδελφός—brother), is a form of polyandry in which a woman is married to two or more men who are brothers. Fraternal polyandry was (and sometimes still is) found in certain areas of Tibet, Nepal, and Northern India, central African cultures[10] where polyandry was accepted as a social practice.[6][11] The Toda people of southern India practice fraternal polyandry, but monogamy has become prevalent recently.[12] In contemporary Hindu society, polyandrous marriages in agrarian societies in the Malwa region of Punjab seem to occur to avoid division of farming land.[13]

Fraternal polyandry achieves a similar goal to that of primogeniture in 19th-century England. Primogeniture dictated that the eldest son inherited the family estate, while younger sons had to leave home and seek their own employment. Primogeniture maintained family estates intact over generations by permitting only one heir per generation. Fraternal polyandry also accomplishes this, but does so by keeping all the brothers together with just one wife so that there is only one set of heirs per generation.[14] This strategy appears less successful the larger the fraternal sibling group is.[15]

Some forms of polyandry appear to be associated with a perceived need to retain aristocratic titles or agricultural lands within kin groups, and/or because of the frequent absence, for long periods, of a man from the household. In Tibet the practice was particularly popular among the priestly Sakya class.

The female equivalent of fraternal polyandry is sororate marriage.

Partible paternity

Anthropologist Stephen Beckerman points out that at least 20 tribal societies accept that a child could, and ideally should, have more than one father, referring to it as "partible paternity".[16] This often results in the shared nurture of a child by multiple fathers in a form of polyandric relation to the mother, although this is not always the case.[17] One of the most well known examples is that of Trobriand "virgin birth". The matrilineal Trobriand Islanders recognize the importance of sex in reproduction but do not believe the male makes a contribution to the constitution of the child, who therefore remains attached to their mother's lineage alone. The mother's non-resident husbands are not recognized as fathers, although the mother's co-resident brothers are, since they are part of the mother's lineage.

Culture

According to inscriptions describing the reforms of the Sumerian king Urukagina of Lagash (ca. 2300 BC), the earlier custom of polyandry in his country was abolished, on pain of the woman taking multiple husbands being stoned upon which her crime is written.[18]

An extreme gender imbalance has been suggested as a justification for polyandry. For example, the selective abortion of female children in India has led to a significant margin in sex ratio and, it has been suggested, results in related men "sharing" a wife.[19]

Known cases

Polyandry in Tibet was a common practice and continues to a lesser extent today. A survey of 753 Tibetan families by Tibet University in 1988 found that 13% practiced polyandry.[20] Polyandry in India still exists among minorities, and also in Bhutan, and the northern parts of Nepal. Polyandry has been practised in several parts of India, such as Rajasthan, Ladakh and Zanskar, in the Jaunsar-Bawar region in Uttarakhand, among the Toda of South India.[6][21]

It also occurs or has occurred in Nigeria, the Nymba,[21] and some pre-contact Polynesian societies,[22] though probably only among higher caste women.[23] It is also encountered in some regions of Yunnan and Sichuan regions of China, among the Mosuo people in China (who also practice polygyny as well), and in some sub-Saharan African such as the Maasai people in Kenya and northern Tanzania[24] and American indigenous communities. The Guanches, the first known inhabitants of the Canary Islands, practiced polyandry until their disappearance.[25] The Zo'e tribe in the state of Pará on the Cuminapanema River, Brazil, also practice polyandry.[26]

Africa

- In the Lake Region of Central Africa, "Polygyny ... was uncommon. Polyandry, on the other hand, was quite common."[27]

- "The Maasai are polyandrous".[28]

- Among the Irigwe of Northern Nigeria, women have traditionally acquired numerous spouses called "co-husbands".

- In August 2013, two Kenyan men entered into an agreement to marry a woman with whom they had both been having an affair. Kenyan law does not explicitly forbid polyandry, although it is not a common custom.[29]

Asia

- In the reign of Urukagina of Lagash, "Dyandry, the marriage of one woman to two men, is abolished."[30]

- M. Notovitck mentioned polyandry in Ladakh or Little 'Tibet' in his record of his journey to Tibet. ("The Unknown life of Jesus Christ" by Virchand Gandhi).

- Polyandry was widely (and to some extent still is) practised in Lahaul-Spiti situated in isolation in the high Himalayas in India.

- In Arabia (southern) "All the kindred have their property in common ...; all have one wife" whom they share.[31]

- The Hoa-tun (Hephthalites, White Huns) "living to the north of the Great Wall ... practiced polyandry."[32] Among the Hephthalites, "the practice of several husbands to one wife, or polyandry, was always the rule, which is agreed on by all commentators. That this was plain was evidenced by the custom among the women of wearing a hat containing a number of horns, one for each of the subsequent husbands, all of whom were also brothers to the husband. Indeed, if a husband had no natural brothers, he would adopt another man to be his brother so that he would be allowed to marry."[33]

- "Polyandry is very widespread among the Sherpas."[34]

- In Bhutan in 1914, polyandry was "the prevailing domestic custom".[35] Nowadays polyandry is rare, but still found for instance among the Brokpas of the Merak-Sakten region.[36]

- In several villages in Nyarixung Township, Xigaze, Tibet, up to 90% of families practiced polyandry in 2008.[37]

- Among the Gilyaks of Sakhalin Island "polyandry is also practiced."[38]

- Fraternal polyandry is permitted in Sri Lanka under Kandyan Marriage law, often described using the euphemism eka-ge-kama (literally "eating in one house").[39] Associated Polyandry, or polyandry that begins as monogamy, with the second husband entering the relationship later, is also practiced[40] and is sometimes initiated by the wife.[41]

- Polyandry was common in Sri Lanka, until it was banned by the British in 1859.

Europe

_-_200505.jpg.webp)

- Reporting on the mating patterns in ancient Greece, specifically Sparta, Plutarch writes: "Thus if an older man with a young wife should take a liking to one of the well-bred young men and approve of him, he might well introduce him to her so as to fill her with noble sperm and then adopt the child as his own. Conversely a respectable man who admired someone else’s wife noted for her lovely children and her good sense, might gain the husband’s permission to sleep with her thereby planting in fruitful soil, so to speak, and producing fine children who would be linked to fine ancestors by blood and family."[42]

- "According to Julius Caesar, it was customary among the ancient Britons for brothers, and sometimes for fathers and sons, to have their wives in common."[43]

- "Polyandry prevailed among the Lacedaemonians according to Polybius."[44] (Polybius vii.7.732, following Timæus)[45]

- "The matrons of Rome flocked in great crowds to the Senate, begging with tears and entreaties that one woman should be married to two men."[46]

- The gravestone of Allia Potestas, a woman from Perusia, describes how she lived peacefully with two lovers, one of whom immortalized her in this famous epigraphic eulogy, dating (probably) from the second century.[47]

North America

- Aleut people in the 19th century.[48]

- During the most abusive times of the slave economy in Saint-Domingue during the Haitian Revolution, mortality was so high that women practised polyandry.

- Inuit[49]

Oceania

- Among the Kanak of New Caledonia, "every woman is the property of several husbands. It is this collection of husbands, having one wife in common, that...live together in a hut, with their common wife."[50]

- Marquesans had "a society in which households were polyandrous".[51]

- Friedrich Ratzel in The History of Mankind[52] reported in 1896 that in the New Hebrides there was a kind of convention in cases of widowhood, that two widowers shall live with one widow.

South America

- "The Bororos ... among them...there are also cases of polyandry."[53]

- "The Tupi-Kawahib also practice fraternal polyandry."[54]

- "...up to 70 percent of Amazonian cultures may have believed in the principle of multiple paternity"[55]

- Mapuche polyandry is rare but not unheard of.[56] The men are often brothers.[56]

Religious attitudes

Hinduism

There is at least one reference to polyandry in the ancient Hindu epic Mahabharata. Draupadi married the five Pandava brothers, as this is what she chose in a previous life. This ancient text remains largely neutral to the concept of polyandry, accepting this as her way of life.[57] However, in the same epic, when questioned by Kunti to give an example of polyandry, Yudhishthira cites Gautam-clan Jatila (married to seven Saptarishis) and Hiranyaksha's sister Pracheti (married to ten brothers), thereby implying a more open attitude toward polyandry in Vedic society.[58]

Judaism

The Hebrew Bible contains no examples of women married to more than one man,[59][60] but its description of adultery clearly implies that polyandry is unacceptable[61][62] and the practice is unknown in Jewish tradition.[63][64] In addition, the children from other than the first husband are considered illegitimate, unless he has already divorced her or died (i.e., a mamzer),[65] being a product of an adulterous relationship.

Christianity

Most Christian denominations in the Western world strongly advocate monogamous marriage, and a passage from the Pauline epistles (1 Corinthians 7) can be interpreted as forbidding polyandry.

Latter-Day Saints

Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, and other early Latter-day Saints, practiced polygamous marriages with several women who were already married to other men. The practice was officially ended with the 1890 Manifesto. Polyandrous marriages did exist, albeit in significantly less numbers, in early LDS history.[66][67]

Islam

Although Islamic marital law allows men to have up to four wives, polyandry is not allowed in Islam.[68][69]

Polyandrous marriages were practiced in pre-Islamic Arabian cultures, but were outlawed during the rise of Islam. Nikah Ijtimah was a pagan tradition of polyandry in older Arab regions which was condemned and abolished during the rise of Islam.[68][70]

In biology

Polyandrous behavior is quite widespread in the animal kingdom, occurring for example in insects, fish, birds, and mammals.

See also

- Legal status of polygamy

- Matrilineality

- Polyandry in India

- Polyandry in Tibet

- Sacred prostitution

- Sexual conflict

- Sexy son hypothesis

- Sperm competition

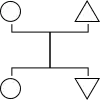

Types of mating, marriage and lifestyle:

References

- McCullough, Derek; Hall, David S. (27 February 2003). "Polyamory - What it is and what it isn't". Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality. 6.

- Zeitzen, Miriam Koktvedgaard (2008). Polygamy: a cross-cultural analysis. Berg. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84520-220-0.

- Ethnographic Atlas Codebook Archived 2012-11-18 at the Wayback Machine derived from George P. Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas recording the marital composition of 1,231 societies from 1960 to 1980.

- Starkweather, Katherine; Hames, Raymond (2012). "A survey of non-classical polyandry". Human Nature (Hawthorne, N.Y.). 23 (2): 149–150. doi:10.1007/s12110-012-9144-x. PMID 22688804. S2CID 2008559.

- Dreger, A. (2013). "When Taking Multiple Husbands Makes Sense". The Atlantic. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Gielen, U. P. (1993). Gender Roles in traditional Tibetan cultures. In L. L. Adler (Ed.), International handbook on gender roles (pp. 413-437). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- (Linda Stone, Kinship and Gender, 2006, Westview, 3rd ed., ch. 6) The Center for Research on Tibet Papers on Tibetan Marriage and Polyandry (accessed October 1, 2006).

- Goldstein, "Pahari and Tibetan Polyandry Revisited" in Ethnology 17(3): 325–327 (1978) (The Center for Research on Tibet; accessed October 1, 2007).

- Levine, Nancy (1998). The Dynamics of polyandry: kinship, domesticity, and population on the Tibetan border. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Banerjee, Partha S. (21 April 2002). "Wild, Windy and Harsh, yet Stunningly Beautiful". The Sunday Tribune.

- Levine, Nancy, The Dynamics of Polyandry: Kinship, domesticity and population on the Tibetan border, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

- Sidner, Sara. "Brothers Share Wife to Secure Family Land". CNN.

- Draupadis bloom in rural Punjab Times of India, Jul 16, 2005.

- Goldstein, Melvyn (1987). Natural History. Natural History Magazine. pp. 39–48.

- Levine, Nancy; Silk, Joan B. (1997). "Why Polyandry Fails: Sources of Instability in Polyandrous marriages". Current Anthropology. 38 (3): 375–98. doi:10.1086/204624. S2CID 17048791.

- Beckerman, S., Valentine, P., (eds) (2002) The Theory and Practice of Partible Paternity in South America, University Press of Florida

- Starkweather, Katie (2009). "A Preliminary Survey of Lesser-Known Polyandrous Societies". Nebraska Anthropologist.

- Engaging the powers: discernment and resistance in a world of domination p. 40 by Walter Wink, 1992 ISBN 0-8006-2646-X

- Arsenault, Chris (24 October 2011). "Millions of aborted girls imbalance India". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

While prospects for conflict are unclear, other problems including human trafficking, prostitution and polyandry—men (usually relatives) sharing a wife—are certain to get worse.

- Ma, Rong (2000). "试论藏族的"一妻多夫"婚姻" (PDF). 《民族学报》 (in Chinese) (6). Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Whittington, Dee (December 12, 1976). "Polyandry Practice Fascinates Prince". The Palm Beach Post. p. 50. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- Goldman I., 1970, Ancient Polynesian Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press'

- Thomas, N. (1987). "Complementarity and History Misrecognizing Gender in the Pacific". Oceania. 57 (4): 261–270. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1987.tb02221.x. JSTOR 40332354.

- The Last of the Maasai. Mohamed Amin, Duncan Willetts, John Eames. 1987. Pp. 86-87. Camerapix Publishers International. ISBN 1-874041-32-6

- "On Polyandry". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. 39 (52): 804. October 1891.

- Starkweather, Kathrine E. (2010). Exploration into Human Polyandry: An Evolutionary Examination of the Non-Classical Cases (Master's thesis). University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- Warren R. Dawson (ed.): The Frazer Lectures, 1922-1932. Macmillan & Co, 1932. p. 33.

- A. C. Hollis: The Masai. p. 312, fn. 2.

- "Kenyan trio in 'wife-sharing' deal". BBC. 26 August 2013.

- J. Bottero, E. Cassin & J. Vercoutter (eds.) (translated by R. F. Tannenbaum): The Near East: the Early Civilizations. New York, 1967. p. 82.

- Strabōn : Geographia 16:4:25, C 783. Translated in Robertson Smith: Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia, p. 158; quoted in Edward Westermarck: The History of Human Marriage. New York: Allerton Books Co., 1922. vol. 3, p. 154.

- Xinjiang Archived May 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Hephthalites of Central Asia". Rick-heli.info. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- René von Nebesky-Wojkowitz (translated by Michael Bullock) :one research done by one organization about Fraternal Polyandry in Nepal and its detail data find here Archived 2011-08-03 at the Wayback Machine Where the Gods are Mountains. New York: Reynal & Co. p. 152.

- L. W. Shakespear : History of Upper Assam, Upper Burmah and North-eastern Frontier. London: Macmillan & Co., 1914. p. 92.

- "Feature: All in the Family", Kuensel 27 August 2007; "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-05-11. Retrieved 2014-12-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Suozhen (2009). 西藏一妻多夫婚姻研究 (in Chinese). China University of Political Science and Law. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Russian Nihilism and Exile Life in Siberia. San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft & Co., 1883. p. 365.

- Hussein, Asiff. "Traditional Sinhalese Marriage Laws and Customs". Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Lavenda, Robert H.; Schultz, Emily A. "Additional Varieties Polyandry". Anthropology: What Does It Mean To Be Human?. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Levine, NE. "Conclusion". Asian and African Systems of Polyandry. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- "Sparta63". Vico.wikispaces.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Henry Theophilus Finck :Primitive Love and Love-Stories. 1899. Archived 2010-06-25 at the Wayback Machine

- John Ferguson McLennon : Studies in Ancient History. Macmillan & Co., 1886. p. xxv

- Henry Sumner Maine : Dissertations on Early Law and Custom. London: John Murray, 1883. Chapter IV, Note B.

- Macrobius (translated by Percival V. Davies): The Saturnalia. New York: Columbia University Press, 1969, p. 53 (1:6:22)

- Horsfall, N:CIL VI 37965 = CLE 1988 (Epitaph of Allia Potestas): A Commentary, ZPE 61: 1985

- Katherine E. Starkweather & Raymond Hames. "A Survey of Non-Classical Polyandry". Human Nature An Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective ISSN 1045-6767 Volume 23 Number 2 Hum Nat (2012) 23:149-172 DOI 10.1007/s12110-012-9144-x 12 Jun 2012.

- Starkweather, Katherine E. and Raymond Hames. "A Survey of Non-Classical Polyandry." 12 June 2012. Retrieved 28 Dec 2013.

- Dr. Jacobs: Untrodden Fields of Anthropology. New York: Falstaff Press, 1937. vol. 2, p. 219.

- Roslyn Poignant: Oceanic Mythology. Paul Hamlyn, London, 1967, p. 69.

- Ratzel, Friedrich. The History of Mankind. (London: MacMillan, 1896)."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-27. Retrieved 2010-04-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Races of Man : an Outline of Anthropology. London: Walter Scott Press, 1901. p. 566.

- C. Lévi-Strauss (translated by John Russell): Tristes Tropiques. New York: Criterion Books, 1961, p. 352.

- "Multiple fathers prevalent in Amazonian cultures, study finds". Sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Millaleo Hernández, Ana Gabriel (2018). Poligamia mapuche / Pu domo ñi Duam (un asunto de mujeres): Politización y despolitización de una práctica en relación a la posición de las mujeres al interior de la sociedad mapuche (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: University of Chile.

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1959). The position of women in Hindu civilization, from prehistoric times to the present day. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 112. ISBN 978-81-208-0324-4. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- "The Mahabharata, Book 1: Adi Parva: Vaivahika Parva: Section CLXLVIII". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Coogan, Michael D., A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context, Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 264,

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W., The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 1, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1980, p. 262,

- Fuchs, Esther, Sexual Politics in the Biblical Narrative: Reading the Hebrew Bible as a Woman, Continuum International, 2000, p. 122,

- Satlow, Michael L., Jewish Marriage in Antiquity, Princeton University Press, 2001, p. 189,

- Witte, John & Ellison, Eliza; Covenant Marriage In Comparative Perspective, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2005, p. 56,

- Marriage, Sex And Family in Judaism, Rowman & Littlefield, 2005, p. 90,

- Murray, John (1991). Principles of Conduct: Aspects of Biblical Ethics. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 250–256. ISBN 978-0-8028-1144-8. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- Richard S. Van Wagoner (1989). Mormon Polygamy: A History (Second ed.). Signature Books. pp. 41–49, 242. ISBN 0941214796.

- Richard S. Van Wagoner (Fall 1985). "Mormon Polyandry in Nauvoo" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought.

- Rehman, J. (2007). "The Sharia, Islamic Family Laws and International Human Rights Law: Examining the Theory and Practice of Polygamy and Talaq". International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family. 21 (1): 114. doi:10.1093/lawfam/ebl023. ISSN 1360-9939.

Polyandry is not permitted, so that Muslim women cannot have more than one husband at the same time

- Wing, AK (2008). "Twenty-First Century Loving: Nationality, Gender, and Religion in the Muslim World". Fordham Law Review. 76 (6): 2900.

Muslim women can only marry one man; no polyandry is allowed.

- Ahmed, Mufti M. Mukarram (2005). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. p. 383. ISBN 978-81-261-2339-1. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

Further reading

- Levine, Nancy, The Dynamics of Polyandry: Kinship, domesticity and population on the Tibetan border, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988. ISBN 0-226-47569-7, ISBN 978-0-226-47569-1

- Peter, Prince of Greece, A Study of Polyandry, The Hague, Mouton, 1963.

- Beall, Cynthia M.; Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1981). "Tibetan Fraternal Polyandry: A Test of Sociobiological Theory". American Anthropologist. 83 (1): 898–901. doi:10.1525/aa.1982.84.4.02a00170.

- Gielen, U. P. (1993). Gender Roles in traditional Tibetan cultures. In L. L. Adler (Ed.), International handbook on gender roles (pp. 413–437). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Goldstein, M. C. (1971). "Stratification, Polyandry, and Family Structure in Central Tibet". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 27 (1): 64–74. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.27.1.3629185. JSTOR 3629185. S2CID 146900571.

- Crook, J., & Crook, S. 1994. "Explaining Tibetan polyandry: Socio-cultural, demographic, and biological perspectives". In J. Crook, & H. Osmaston (Eds.), Himayalan Buddhist Villages (pp. 735–786). Bristol, UK: University of Bristol.

- Goldstein, M. C. (1971). "Stratification, Polyandry, and Family Structure in Central Tibet". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 27 (1): 64–74. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.27.1.3629185. JSTOR 3629185. S2CID 146900571.

- Goldstein, M. C. (1976). "Fraternal Polyandry and Fertility in a High Himalayan Valley in Northwest Nepal". Human Ecology. 4 (3): 223–233. doi:10.1007/bf01534287. JSTOR 4602366. S2CID 153817518.

- Lodé, Thierry (2006) La Guerre des sexes chez les animaux. Paris: Eds O. Jacob. ISBN 2-7381-1901-8

- Smith, Eric Alden (1998). "Is Tibetan polyandry adaptive?" (PDF). Human Nature. 9 (3): 225–261. doi:10.1007/s12110-998-1004-3. PMID 26197483. S2CID 3022928.

- Trevithick, Alan (1997). "On a Panhuman Preference for Monandry: Is Polyandry an Exception?". Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 28 (3): 154–81.

External links

| Look up polyandry in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Another example for polyandry in India