Bride price

Bride price, bridewealth,[1] or bride token, is money, property, or other form of wealth paid by a groom or his family to the family of the woman he will be married to or is just about to marry. Bride price can be compared to dowry, which is paid to the groom, or used by the bride to help establish the new household, and dower, which is property settled on the bride herself by the groom at the time of marriage. Some cultures may practice both dowry and bride price simultaneously. Many cultures practiced bride pricing prior to existing records.

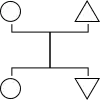

| Part of a series on the |

| Anthropology of kinship |

|---|

|

|

Social anthropology Cultural anthropology |

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

The tradition of giving bride price is practised in many Asian countries, the Middle East, parts of Africa and in some Pacific Island societies, notably those in Melanesia. The amount changing hands may range from a token to continue the traditional ritual, to many thousands of US dollars in some marriages in Thailand, and as much as a $100,000 in exceptionally large bride prices in parts of Papua New Guinea where bride price is customary.

Function

Bridewealth is commonly paid in a currency that is not generally used for other types of exchange. According to French anthropologist Philippe Rospabé, its payment does therefore not entail the purchase of a woman, as was thought in the early twentieth century. Instead, it is a purely symbolic gesture acknowledging (but never paying off) the husband's permanent debt to the wife's parents.[2]

Dowries exist in societies where capital is more valuable than manual labor. For instance, in Middle-Age Europe, the family of a bride-to-be was compelled to offer a dowry —- land, cattle and money —- to the family of the husband-to-be. Bridewealth exists in societies where manual labor is more important than capital. In Sub-Saharan Africa where land was abundant and there were few or no domesticated animals, manual labor was more valuable than capital, and therefore bridewealth dominated.

An evolutionary psychology explanation for dowry and bride price is that bride price is common in polygynous societies which have a relative scarcity of available women. In monogamous societies where women have little personal wealth, dowry is instead common since there is a relative scarcity of wealthy men who can choose from many potential women when marrying.[3]

Historical usage

Mesopotamia

The Code of Hammurabi mentions bride price in various laws as an established custom. It is not the payment of the bride price that is prescribed, but the regulation of various aspects:

- a man who paid the bride price but looked for another bride would not get a refund, but he would if the father of the bride refused the match

- if a wife died without sons, her father was entitled to the return of her dowry, minus the value of the bride price.[4]

Jewish tradition

The Hebrew Bible mention the practice of paying a bride price to the father of a virgin, an unmarried young woman. Exodus 22:16-17 states CEV Exodus 22:16-17 Suppose a young woman has never had sex and isn't engaged. If a man talks her into having sex, he must pay the bride price and marry her. But if her father refuses to let her marry the man, the bride price must still be paid. NASB Exodus 22:16-17 “If a man seduces a virgin who is not engaged, and lies with her, he must pay a dowry for her to be his wife. “If her father absolutely refuses to give her to him, he shall pay money equal to the dowry for virgins.

KJ2000 Deuteronomy 22:28-29 similarly states:

28 If a man find a young woman that is a virgin, who is not betrothed, and lay hold on her, and lie with her, and they be found;

29 Then the man that lay with her shall give unto the young woman's father fifty shekels of silver, and she shall be his wife; because he has violated her, he may not put her away all his days.

In the Jewish tradition, the rabbis in ancient times insisted on the marriage couple's entering into a marriage contract, called a ketubah. The ketubah provided for an amount to be paid by the husband in the event of a divorce (get) or by his estate in the event of his death. This amount was a replacement of the biblical dower or bride price, which was payable at the time of the marriage by the groom.

This innovation came about because the bride price created a major social problem: many young prospective husbands could not raise the amount at the time when they would normally be expected to marry. So, to enable these young men to marry, the rabbis, in effect, delayed the time that the amount would be payable, when they would be more likely to have the sum. It may also be noted that both the dower and the ketubah amounts served the same purpose: the protection for the wife should her support (either by death or divorce) cease. The only difference between the two systems was the timing of the payment.

In fact, the rabbis were so insistent on the bride having the "benefit of the ketubah" that some even described a marriage without one as being merely concubinage, because the bride would lack the benefit of the financial settlement in case of divorce or death of the husband, and without the dower or ketubah amount the woman and her children could become a burden on the community. However, the husband could refuse to pay the ketubah amount if a divorce was on account of adultery of the wife.

In traditional Jewish weddings, to this day, the groom gives the bride an object of value, such as a wedding ring.[5] The ring must have a certain minimal value, and it is considered to be a way to fulfill the halachic legal requirement of the husband making a payment to or for the bride.

Ancient Greece

Some of the marriage settlements mentioned in the Iliad and Odyssey suggest that bride price was a custom of Homeric society. The language used for various marriage transactions, however, may blur distinctions between bride price and dowry, and a third practice called "indirect dowry," whereby the groom hands over property to the bride which is then used to establish the new household.[6]:177 "Homeric society" is a fictional construct involving legendary figures and deities, though drawing on the historical customs of various times and places in the Greek world.[6]:180 At the time when the Homeric epics were composed, "primitive" practices such as bride price and polygamy were no longer part of Greek society. Mentions of them preserve, if they have a historical basis at all, customs dating from the Age of Migrations (c. 1200–1000 BC) and the two centuries following.[6]:185

In the Iliad, Agamemnon promises Achilles that he can take a bride without paying the bride price (Greek hednon), instead receiving a dowry (pherne).[6]:179[7] In the Odyssey, the least arguable references to bride price are in the marriage settlements for Ctimene, the sister of Odysseus;[8] Pero, the daughter of Neleus, who demanded cattle for her;[9] and the goddess Aphrodite herself, whose husband Hephaestus threatens to make her father Zeus return the bride price given for her, because she was adulterous.[6]:178 It is possible that the Homeric "bride price" is part of a reciprocal exchange of gifts between the prospective husband and the bride's father, but while gift exchange is a fundamental practice of aristocratic friendship and hospitality, it occurs rarely, if at all, in connection with marriage arrangements.[6]:177–178

Islamic law

Islamic law commands a groom to give the bride a gift called a Mahr prior to the consummation of the marriage. A mahr differs from the standard meaning of bride-price in that it is not to the family of the bride, but to the wife to keep for herself; it is thus more accurately described as a dower. In the Qur'an, it is mentioned in chapter 4, An-Nisa, verse 4 as follows:

And give to the women (whom you marry) their Mahr [obligatory bridal money given by the husband to his wife at the time of marriage] with a good heart; but if they, of their own good pleasure, remit any part of it to you, take it and enjoy it without fear of any harm (as Allah has made it lawful). Useful information about bridal dowry in Iran

Morning gifts

Morning gifts, which might be arranged by the bride's father rather than the bride, are given to the bride herself. The name derives from the Germanic tribal custom of giving them the morning after the wedding night. The woman might have control of this morning gift during the lifetime of her husband, but is entitled to it when widowed. If the amount of her inheritance is settled by law rather than agreement, it may be called dower. Depending on legal systems and the exact arrangement, she may not be entitled to dispose of it after her death, and may lose the property if she remarries. Morning gifts were preserved for many centuries in morganatic marriage, a union where the wife's inferior social status was held to prohibit her children from inheriting a noble's titles or estates. In this case, the morning gift would support the wife and children. Another legal provision for widowhood was jointure, in which property, often land, would be held in joint tenancy, so that it would automatically go to the widow on her husband's death.

Contemporary

Africa

In parts of Africa, a traditional marriage ceremony depends on payment of a bride price to be valid. In Sub-Saharan Africa, bride price must be paid first in order for the couple to get permission to marry in church or in other civil ceremonies, or the marriage is not considered valid by the bride's family. The amount can vary from a token to a great sum, real estate and other values. Lobolo (or Lobola, sometimes also known as Roora) is the same tradition in most cultures in Southern Africa Xhosa, Shona, Venda, Zulu, Ndebele etc. The amount includes a few to several herd of cattle, goats and a sum of money depending on the family. The cattle and goats constitute an integral part of the traditional marriage for ceremonial purposes during and after the original marriage ceremony.

The animals and money are not always paid all at once. Depending on the wealth of the groom he and his family can enter into a non written contract with the bride's family similar to the Jewish Ketubah, in which he promises to pay what he owes within a specified period of time. This is done to allow young men who do not have much to marry while they work towards paying off the bride price as well as raising a family or wait for their own sisters and aunts to get married so they in turn can use the amounts received to offset their debts to their in-laws. This amount must be paid by his family in the event he is incapacitated or dies. It is considered a family debt of honor.

In some societies, marriage is delayed until all payments are made. If the wedding occurs before all payments are made, the status is left ambiguous.[10] The bride price tradition can have destructive effects when young men don't have the means to marry. In strife-torn South Sudan, many young men steal cattle for this reason, often risking their lives.[11] In mid twentieth century Gabon a person's whole life can be governed by the money affairs connected with marriage; to secure a wife for their son, parents begin to pay installments for a girl of only a few years; from the side of the wife's family there begins a process of squeezing which goes on for years.[12]

In the African Great Lakes country of Uganda, the MIFUMI Project[13] held a referendum in Tororo in 2001 on whether a bride price should be a non-refundable gift. In 2004, it held an international conference on the bride price in Kampala, Uganda. It brought together activists from Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, Rwanda and South Africa to discuss the effect that payment of bride price has on women. Delegates also talked about ways of eliminating this practice in Africa and elsewhere. It also issued a preamble position in 2008.[14] In 2007 MIFUMI took the Uganda Government to the Constitutional Court wishing the court to rule that the practice of Bride Price is un-constitutional. Especially it was complained, that the bride price once taken, should not be refundable if the couple should get a divorce.

The Mifumi petition on bride price was decided in 2010 by the Constitutional Court of Uganda when four judges to one (with Justice Tumwesigye dissenting) upheld the constitutionality of bride price (See Constitutional Court of Uganda (2010) Mifumi (U) Ltd & 12 Others v Attorney General, Kenneth Kakuru (Constitutional Petition No.12 Of 2007) [2010] UGCC 2 (26 March 2010. This was despite finding that certain elements of the custom of bride price, such as the demand for refund, was not only unconstitutional but also criminal. However all was not lost because the case significantly advanced African jurisprudence, particularly in the views of the judges expressed obiter dicta in their judgements.

More importantly, MIFUMI appealed and in 2015 the Supreme Court of Uganda ruled that the custom of bride price refund was unconstitutional and therefore outlawed (See (See Supreme Court of Uganda (2015) Mifumi (U) Ltd & Anor Vs Attorney General & Anor (Constitutional Appeal No. 02 of 2014) [2015] UGSC 13).

As the following will show, bride price far from being a concern of a far removed NGO such as MIFUMI, has been an issue for women in the transition from colonialism to nation-building. In his article ‘Bride Wealth (Price) and Women’s Marriage – Related Rights in Uganda: A Historical Constitutional Perspective and Current Developments’, the legal scholar Jamil Ddamulira Mujuzi, in analyses the MIFUMI petition argues that “had the Court considered international law, especially the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women’s concluding observation on Uganda’s May 2009 report to the same Committee, it would probably have concluded that the practice of bride wealth is against Uganda’s international human rights obligations” (Mujuzi, 2010, p. 1). Mujuzi also argues that had the Constitutional Court considered the history of bride price in Uganda, they would have realised that the issue of bride price had appeared in the context of the drafting history of the Constitution of Uganda.

As well as failing to observe the constitution and bring Uganda into line with international rulings on the treatment of women, the court failed to revisit arguments relating to bride price put forward during earlier family law reforms (Kalema, 1965) and constitutional reforms (Odoki, 1995). During the Commission of Enquiry into Women's Status in Marriage and Divorce (Kalema, 1965), only one of the six commissioners was a woman, and the sampling of opinions on the issue was heavily biased in favour of men. This was reflected in one of the main recommendations of the commission, namely the retention of bride wealth, despite strong complaints by women about the practice (Tamale, 1993, as cited in Oloka and Tamale, 1995, p. 725).

The second opportunity where law reform could have had a positive impact was during the constitution-making process in the early 1990s, when the Constitutional Commission recorded the arguments for and against the practice of bride price, but recommended its retention as a cultural practice. Again, some delegates, especially women, called for bride price to be abolished, but their arguments did not attract much attention, and most men supported its retention. Far from this being a new case by a human rights NGO, all the ingredients whereby MIFUMI was to challenge the constitutionality of the practice of bride price had already been laid down during this consultative process, but women's voices were silenced.

MIFUMI appealed to the Supreme Court against the decision of the Constitutional Court that dismissed their petition (See Supreme Court of Uganda (2015) Mifumi (U) Ltd & Anor Vs Attorney General & Anor (Constitutional Appeal No. 02 of 2014) [2015] UGSC 13. On 6 August 2015, by a majority of six to one (with Justice Kisaakye dissenting), the Supreme Court judges unanimously declared the custom of refunding bride price on the dissolution of a customary marriage was ruled unconstitutional. However, it also ruled that held that bride price does not fetter the free consent of persons intending to marry, and consequently, is not in violation of Article 31(3) of the Constitution. Accordingly, our appeal partly succeeded and partly failed.

On the issue of refund, Justice Tumwesigye further held: “In my view, it is a contradiction to say that bride price is a gift to the parents of the bride for nurturing her, then accept as proper demand for a refund of the gift at the dissolution of marriage” (MIFUMI Case 2015, p. 44). He added that:

“The custom of refund of bride price devalues the worth, respect and dignity of a woman; ... ignores the contribution of the woman to the marriage up to the time of its breakdown; ... is unfair to the parents and relatives of the woman when they are asked to refund the bride price after years of marriage; ... may keep the woman in an abusive marital relationship for fear that her parents may be in trouble owing to their inability to refund bride price; ... and makes marriage contingent on a third party.“ (MIFUMI Case 2015, pp. 44–46)

Justice Kisaakye agreed: “Given the dire consequences that a woman, her family and partner may face from a husband who is demanding refund of his bride price, it is not far-fetched to envisage that the requirement to refund bride price may force women to remain in abusive/failed marriage against their will” (p. 68).

In his analysis of the MIFUMI case, the legal scholar Professor Chuma Himonga (2017, p. 2), compares bride price to lobola in South Africa, and concludes that “Essentially, the judgment confirms that bride price has both positive and negative consequences with respect to women’s rights”. He added that “Mifumi dealt with a very important custom in customary marriage - the payment of lobola towards the institution of a marriage, and its repayment at the conclusion and dissolution of a marriage. This custom is one of the most contested aspects of customary marriages from the perspective of women’s rights”.

The decision of the Supreme Court to outlaw bride price refund was a major step forward in the advancement of women's rights. This was a landmark ruling that set a precedent throughout Africa, where bride price had not been challenged as a human rights issue in a court of law. Though the decision was conservative in upholding that bride price per se is constitutional, and in this regard yielded only incremental progress, its outlawing of bride price refund will act as a catalyst for other human rights demands that are implicit in such issues as polygamy, wife inheritance and FGC. However the outcome lent weight to the argument that society is the first to change, and it's only later that the law catches up with it.

In the Supreme Court, Justice Tumwesigye in his lead judgement acknowledged that the commercialisation of bride price “has also served to undermine respect for the custom” (MIFUMI Case, 2015, p. 26). Justice Tumwesigye also acknowledged that the issue of parents in some Ugandan communities removing their under-age daughters from school and forcing them to marry in order to get their children's bride price had been widely reported by NGOs concerned with children's welfare, and given extensive coverage by the media; he agreed that it reflected poorly on law enforcement agencies.

However, whether bride price can be a positive thing remains questionable. I would support Mujuzi (2010) when he says that to protect such women, it is important that Uganda “domesticates” international law. Although Uganda ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 1985, at the time of writing it has yet to domesticate that treaty. Mujuzi argues that unlike the constitutions of South Africa and Malawi, which expressly require courts to refer to international law when interpreting the respective Bill of Rights, the Ugandan Constitution has no such requirement. He recommends that Uganda should amend its constitution accordingly. Such an amendment would ensure that one need not rely on the discretion of the presiding judge to decide whether or not to refer to international law.

Changing customary law on bride price in Uganda is difficult as it is guarded by society, which is especially in the rural areas approving its relevance. The whole culture of the People of Ankole is deeply connected to the institution of bride price. Its custom connects families for a lifetime and women are proud on the extremely high value they receive, comparing to the Baganda or the Rwandese. It is not rare, that the groom has to give his bride huge amounts of cattle and also a house, car and other property. Of course depending on the "value" of the bride (schooling, degrees) but also on his own possibilities. This corresponds with the bride price customs in China; the rich one has to give - otherwise it can be even taken by the brides family forcefully. On the other hand, a rich man marrying an educated woman, who has spent millions on her education in the expensive Ugandan education system, are willing and proud to "show up" and pay. To show the whole world - and especially the whole family of the bride - who they are and what richness they achieved. It's a question of honor. But there are also others, who take loans to be paid back within many years, just to marry the woman they love. In other instances, people marry at an advanced age, as they still need more time to acquire enough property to marry their wives officially. Customary law is also considered more than just bride price but other rituals and ceremonies that enrich Ugandan cultures.

Of course, next to constitutional changes, changes in customary law would be necessary to abolish the practice.[15] And customary law is not changeable by decision, but develops itself alone...

In sub-Saharan Africa, the visits between families to negotiate the bride price are traditional customs that are considered by many Africans to be central to African marriage and society. The negotiations themselves have been described as the crucial component of the practice as they provide the families of the bride and groom the opportunity to meet and forge important bonds. The price itself, independent on his value, is symbolic, although the custom has also been described as "the license of owning a family in the African institution of marriage".[16] In some African cultures, the price of a bride is connected with her reputation and esteem in the community (Ankole, Tooro), an aspect that has been by foreighners criticized as demeaning to women. In some African cultures, such as the Fang people in Equatorial Guinea, and some regions in Uganda, the price is considered the "purchase price" of a wife. One point of critics says, that the husband so might exercise economic control over her.

The majority ethnic group of Equatorial Guinea, the Fang people practise the bride price custom in a way that subjugates women who find themselves in an unhappy marriage. Divorce has a social stigma among the Fang, and in the event that a woman intends to leave her husband, she is expected to return the goods initially paid to her family. If she is unable to pay the debt, she can be imprisoned. Although women and men in theory have equal inheritance rights, in practise men are normally the ones to inherit property. This economic disadvantage reinforces women's lack of freedom and lower social status.[17]

The common term for the arrangement in southern Africa is lobolo, from the Nguni language, a term often used in central and western Africa as well. Elders controlled the marriage arrangements. In South Africa, the custom survived colonial influences, but was transformed by capitalism. Once young men began working in mines and other colonial businesses, they gained the means to increase the lobolo, leading elders to increase the value required for lobolo in order to maintain their control.[18]

It is also practised by Muslims in North Africa and is called Mahr.

Western Asia

Assyrians, who are indigenous people of Western Asia, commonly practice the bride price (niqda) custom. The tradition would involve the bridegroom's family paying to the father of the bride. The amount of money of the niqda is reached at by negotiation between groups of people from both families. The social state of the groom's family influences the amount of the bridewealth that ought to be paid. When the matter is settled to the contentment of both menages, the groom's father may kiss the hand of the bride's father to express his chivalrous regard and gratitude. These situations are usually filmed and incorporated within the wedding video. Folk music and dancing is accompanied after the payment is done, which usually happens on the doorstep, before the bride leaves her home with her escort (usually a male family member who would then walk her into the church).[19] It is still practised by Muslims in the region and is called Mahr.

Central Asia

In many parts of Central Asia nowadays, bride price is mostly symbolic. Various names for it in Central Asia include Kazakh: қалыңмал [qaləɴmal], Kyrgyz: калың [qɑlɯ́ŋ], Uzbek: qalin [qalɨn], and Russian: калым [kɐˈɫɨm]. It is also common in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.[20] The price may range from a small sum of money or a single piece of livestock to what amounts to a herd of livestock, depending on local traditions and the expectations and agreements of the families involved.[21] The tradition is upheld in Afghanistan. A "dark distortion" of it involved a 6-year-old daughter of an Afghan refugee from Helmand Province in a Kabul refugee camp, who was to be married to the son of the money lender who provided with the girl's father $2500 so the man could pay medical bills. According to anthropologist Deniz Kandiyoti, the practice increased after the fall of the Taliban.[22] It is still practised by Muslims in the region and is called Mahr.

Thailand

In Thailand, bride price—sin sod[23] (Thai: สินสอด, pronounced [sĭn sòt] and often erroneously referred to by the English term "dowry") is common in both Thai-Thai and Thai-foreign marriages. The bride price may range from nothing—if the woman is divorced, has a child fathered by another man, or is widely known to have had premarital relations with men—to tens of millions of Thai baht (US$300,000 or ~9,567,757 THB) for a woman of high social standing, a beauty queen, or a highly educated woman. The bride price in Thailand is paid at the engagement ceremony, and consists of three elements: cash, Thai (96.5 percent pure) gold, and the more recent Western tradition of a diamond ring. The most commonly stated rationale for the bride price in Thailand is that it allows the groom to demonstrate that he has enough financial resources to support the bride (and possibly her family) after the wedding. In many cases, especially when the amount is large, the parents of a Thai bride will return all or part of the bride price to the couple in the form of a wedding gift following the engagement ceremony.

It is also practised by Muslims in Thailand and is called Mahr.

Kachin

In Kachin society they have the system of Mayu and Dama. "Mayu" means a group of people who give woman and "Dama" means a group of people who take woman. The “bride wealth” system is extremely important for kinship system in Kachin society and has been used for centuries. The purpose of giving "bride wealth" is to honor the wife giver "Mayu" and to create a strong relationship. The exact details of the “bride wealth” system vary by time and place. In Kachin society, bride wealth is required to be given by wife taker “Dama” to wife giver “Mayu.” Kachin ancestors thought that if wife takers “Dama” gave a large bride price to wife giver “Mayu”; it meant that they honored the bride and her family, and no one would look down on the groom and bride.[24]

China

In traditional Chinese culture, an auspicious date is selected to ti qin (simplified Chinese: 提亲; traditional Chinese: 提親; lit. 'propose marriage'), where both families will meet to discuss the amount of the bride price (Chinese: 聘金; pinyin: pìn jīn) demanded, among other things. Several weeks before the actual wedding, the ritual of guo da li (simplified Chinese: 过大礼; traditional Chinese: 過大禮; lit. 'going through the great ceremony') takes place (on an auspicious date). The groom and a matchmaker will visit the bride's family bearing gifts like wedding cakes, sweetmeats and jewelry, as well as the bride price. On the actual wedding day, the bride's family will return a portion of the bride price (sometimes in the form of dowry) and a set of gifts as a goodwill gesture.

Bride prices vary from CN¥ 1,000,000 in famously money-centric[25][26] Shanghai[27][28] to as little as CN¥ 10,000.[29][30] A house is often required along with the bride price[31] (an apartment is acceptable, but rentals are not[32]) and a car under both or only the bride's name,[28][30] neither of which are counted toward the bride price itself. In some regions, the bride's family may demand other kinds of gifts,[33] none counted toward the bride price itself. May 18 is a particularly auspicious day on which to pay the bride price and marry as its Chinese wording is phoenetically similar to "I will get rich".[27] Bride prices are rising quickly[32][34] in China [27] largely without documentation but a definite verbal and cultural understanding of where bride prices are today. Gender inequality in China has increased competition for ever higher bride prices.[35] Financial distress is an unacceptable and ignored justification for not paying the bride price. If the grooms' side cannot agree or pay, they or simply the groom himself must still pay a bride price [36] thus borrowing from relatives is a popular if not required option to "save face". Inability to pay is cause for preventing a marriage which either side can equally recommend. Privately, families need bride prices due to China's lack of a social security net[37] and a one child policy which leaves parents with neither retirement funding nor caretaking if their only child is taken away[38] as brides typically move into the groom's residence upon marrying[39] as well as testing the groom's ability to marry by paying cash [39] and emotionally giving up his resources to the bride.[40] Publicly, families cite bride price as insurance in case the man abandons or divorces the wife[40] and that the bride price creates goodwill between families. The groom's side should pay more than what the bride's side has demanded[41] to "save face".[35][42] Amounts preferably follow the usual red envelope conventions though the sum is far more important.

Changing patterns in the betrothal and marriage process in some rural villages of modern China can be represented as the following stages:[43]

- Ti qin 提亲, "propose a marriage";

- He tian ming 和天命, "Accord with Heaven's mandate" (i.e. find a ritually auspicious day);

- Jian mian 见面, "looking in the face", i.e. meeting;

- Ding hun 订婚, "being betrothed";

- Yao ri zi 要日子, "asking the wifegivers the date of the wedding"; and

- Jie xin ren 接新人, "transferring the bride".

It is also practised by Muslims known as Uyghurs in Xinjiang and is called Mahr.

Indian subcontinent

It is still practised by Muslims in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and is called Mahr. In North East India, notably in Assam (the indigenous Assamese ethnic groups) an amount or token of bride price was and is still given in various forms.

Myanmar

It is still practised by Muslims, known as Rohingyas in Myanmar, especially in Rakhine State and is called Mahr.

Papua New Guinea

Traditional marriage customs vary widely in Papua New Guinea. At one extreme are moiety (or 'sister exchange') societies, where a man must have a real or classificatory sister to give in exchange for a wife, but is not required to pay a bride price as is understood elsewhere in the country. At the other extreme are resource rich areas of the Papua New Guinea Highlands, where locally traded valuables in the form of shells and stone axes, were displaced by money and modern manufactures (including vehicles and white goods) during the 20th century. Extremely high bride prices are now paid in the Highlands, where even ordinary village men are expected to draw on their relations to pay their wive's relatives pigs and cash to the value of between $5,000 and $10,000. Where either or both of the couple is university-educated or well-placed in business or politics, the amount paid may escalate to $50,000-$100,000 when items like a new bus or Toyota 4WD are taken into account. Bride prices may be locally inflated by mining royalties, and are higher near the economically more prosperous national capital, Port Moresby.

For most couples in most provinces, however, if a bride price is paid, it will amount to up to a dozen pigs, domestic goods, and more amounts of cash.

Solomon Islands

There is a tradition of payment of bride price on the island of Malaita in the Solomon Islands, although the payment of brideprice is not a tradition on other islands. Malaitan shell-money, manufactured in the Langa Langa Lagoon, is the traditional currency used in Malaita and throughout the Solomon Islands. The money consists of small polished shell disks which are drilled and placed on strings. It can be used as payment for brideprice, funeral feasts and compensation, with the shell-money having a cash equivalent value. It is also worn as an adornment and status symbol. The standard unit, known as the tafuliae, is several strands 1.5 m in length. The shell money is still produced by the people of Langa Langa Lagoon, but much is inherited, from father to son, and the old traditional strings are now rare.

In fiction

- A famous Telugu play Kanyasulkam (Bride Price) satirised the practice and the brahminical notions that kept it alive. Though the practice no longer exists in India, the play, and the movie based on it, are still extremely popular in Andhra Pradesh.

- A popular Mormon film, Johnny Lingo, set in Polynesia, uses the device of a bride price of a shocking amount in one of its most pivotal scenes.

- The plot of "A Home for the Highland Cattle", a short story by Doris Lessing hinges on whether a painting of cattle can be accepted in place of actual cattle for "lobola", bride price in a southern African setting.

- Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta wrote a novel titled The Bride Price (1976).

- The Silmaril given by Beren to Thingol in Tolkien's legendarium is described by Aragorn in The Fellowship of the Ring as "the bride price of Lúthien".

See also

References

- Dalton, George (1966). "Brief Communications: "Bridewealth" vs. "Brideprice"". American Anthropologist. 68 (3): 732–737. doi:10.1525/aa.1966.68.3.02a00070.

- Graeber, David (2011). Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Melville House. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-1-933633-86-2.

- The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Edited by Robin Dunbar and Louise Barret, Oxford University Press, 2007, Chapter 26, "The evolutionary ecology of family size".

- Hammurabi & 163-164

- The Jewish Way in Love & Marriage, Rabbi Maurice Lamm, Harper & Row, 1980, Chapter 15

- Snodgrass, A.M. (2006). Archaeology and the Emergence of Greece'. Cornell University Press.

- Iliad 9.146

- Odyssey 15.367.

- Odyssey 11.287–297 and 15.231–238. The two versions vary, but the bride price demanded takes the form of a mythological test, labor, or ordeal; William G. Thalman, The Swineherd and the Bow: Representations of Class in the Odyssey (Cornell University Press, 1998), p. 157f.

- Africa. Grosz-Ngaté, Maria Luise,, Hanson, John H., 1956-, O'Meara, Patrick (Fourth ed.). Bloomington. 2014-04-18. ISBN 9780253013026. OCLC 873805936.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Aleu, Philip Thon & Mach, Parach (26 June 2016). "Risking one's life to be able to marry". D+C, development and cooperation. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- Schweitzer, Albert. 1958. African Notebook. Indiana University Press

- "The MIFUMI Project". Archived from the original on 2009-05-18. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ""MIFUMI Preamble on Bride Price for Tororo Ordinance 2008"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- "Development and Cooperation, Vol.36, 2009, No.11". Archived from the original on 2010-01-03. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- Waweru, Humphrey (2012). The Bible and African Culture. Mapping Transactional Inroads. African Books Collective. p. 170. ISBN 9789966150639.

- Stange, Mary Zeiss; Carol K. Oyster; Jane E. Sloan (2011). Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World, Volume 1. SAGE. p. 496. ISBN 9781412976855.

- Bennett, T.W. (2004). Customary Law in South Africa. Kluwer. p. 223. ISBN 9780702163616.

- "Assyrian Rituals of Life-Cycle Events by Yoab Benjamin". Archived from the original on 2019-11-28. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (1993). Religious policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. pp. 220.

- Rakhimdinova, Aijan. "Kyrgyz Bride Price Controversy". IWPR Issue 17, 22 Dec 05. IWPR. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- Rubin, Alissa J. (1 April 2013). "Afghan Debt's Painful Payment: A Daughter, 6". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "Cultural aspects within marriage" (Video). Bangkok Post. 2015-04-28. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- Num Wawn Num La Shaman Ga hte Htinggaw Mying Gindai,2010, Mougaung Baptist Church

- French, Howard W. (2006-01-24). "In a Richer China, Billionaires Put Money on Marriage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-05-05. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- French, Howard W. (2006-01-23). "Rich guy seeks girl, must be virgin: Read this ad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- Faison, Seth (1996-05-22). "Shanghai Journal;It's a Lucky Day in May, and Here Come the Brides". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-04-18. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- Larmer, Brook (2013-03-09). "In a Changing China, New Matchmaking Markets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-03-24. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- "全国聘礼地图:山东3斤百元人民币 重庆0元(图)". 2013-06-05. Archived from the original on 2014-04-17. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- "The Price of Marriage in China: Infographic Shows Astounding Data". 2013-06-11. Archived from the original on 2014-04-17. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- Gwynn Guilford, Ritchie King & Herman Wong (June 9, 2013). "Forget dowries: Chinese men have to pay up to US$24,000 to get a bride". Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Lim, Louisa (April 23, 2013). "For Chinese Women, Marriage Depends On Right 'Bride Price'". Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Trivedi, Anjani (June 10, 2013). "The Steep Price for a Chinese Bride". Time. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- "全国聘礼地图". 2013-06-06. Archived from the original on 2014-04-19. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- Moore, Malcolm (January 4, 2013). "China's brides go for gold as their dowries get bigger and bigger". Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- "I have a solution". 2012-03-25. Archived from the original on 2016-11-30. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- "PIN JIN OR BRIDE PRICE IN SINGAPORE .. HOW MUCH TO PAY?". April 27, 2013. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Lisa Mahapatra & Sophie Song (June 6, 2013). "A Map Of China's Bride Price Distribution: Shanghai Tops The List At One Million Yuan And Chongqing The Only City Where Love Is Free". Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Roberts, Marcus (June 12, 2013). "Chinese "Bride Price"". Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- "Bride Price (聘金): How Much To Give?". Archived from the original on 2014-04-19. Retrieved 2014-04-17.

- "Chinese Wedding Traditions: The Bride Price". August 26, 2012. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- "How Much Are You Worth, Chinese Bride-to-Be?". April 24, 2013. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Han, Min, "Social Change and Continuity in a Village in Northern Anhui, China: A Response to Revolution and Reform" Archived 2009-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, Senri Ethnological Studies 58, Osaka, Japan: National Museum of Ethnology, December 20, 2001.

Further reading

- Hirsch, Jennifer S., Wardlow, Holly, Modern loves: the anthropology of romantic courtship & companionate marriage, Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 0-472-09959-0. Cf. Chapter 1 "Love and Jewelry", on the bride price.