Politics of Scotland

The politics of Scotland operate within the constitution of the United Kingdom, of which Scotland is a home nation. Scotland is a democracy, which since the Scotland Act 1998 has been represented in both the Scottish Parliament – the legislature to which most legislative powers are devolved – and the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Most executive power is exercised by the Scottish Government, led by the First Minister of Scotland, the head of government in a multi-party system. The judiciary of Scotland, dealing with Scots law, is independent of the legislature and the executive. Scots law is primarily determined by the Scottish Parliament, excepting in areas deemed reserved and excepted matters. The Scottish Government shares some executive powers with the Government of the United Kingdom's Scotland Office, a British government department led by the Secretary of State for Scotland.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Scotland |

|---|

|

|

|

In the Scottish Parliament, the inhabitants of Scotland are represented by 129 members of the Scottish Parliament, who elected are elected by the additional member system, a form of proportional representation, by the Scottish Parliament constituencies and electoral regions. It enacts primary legislation through Acts of the Scottish Parliament, but cannot legislate on matters reserved to the British parliament by the Scotland Act 1998, and amended by the Scotland Act 2012 and the Scotland Act 2016. In the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, 59 members of parliament represent Scotland's parliamentary constituencies, each elected by first-past-the-post voting. Scotland is also represented by some life peers in the House of Lords, and by Scottish hereditary peers excepted under the House of Lords Act 1999.

The first minister leads the Scottish Government and the Cabinet of Scotland, which consists of Cabinet Secretaries, Junior Ministers, and Law Officers. The Scottish Government governs through Scottish statutory instruments, a type of subordinate legislation, and is responsible for the Directorates of the Scottish Government, the executive agencies of the Scottish Government, and the other public bodies of the Scottish Government. The directorates include the Scottish Exchequer, the Economy Directorates, the Health and Social Care Directorates, and the Education, Communities and Justice Directorates. Statutory instruments made by the British Government – within which the Secretary of State for Scotland is a member of the Cabinet of the United Kingdom – may also apply to the whole of Great Britain. The Secretary of State for Scotland is appointed by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

The Courts of Scotland administer justice in Scots law, the legal system in Scotland. The Lord Advocate is the chief legal officer of the Scottish Government and the Crown in Scotland for both civil and criminal matters for which Scottish Parliament has devolved responsibilities. The Lord Advocate is the chief public prosecutor for Scotland and all prosecutions on indictment are conducted by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, nominally in the Lord Advocate's name. The Lord Advocate's deputy, the Solicitor General for Scotland, advises the Scottish Government on legal matters. The Advocate General for Scotland advises the British Government, and leads the Office of the Advocate General for Scotland, a British government department. The High Court of Justiciary is the superior criminal court of Scotland. The Court of Session is the highest civil court and is both a court of first instance and a court of appeal. For judicial purposes, Scotland has been divided into six sheriffdoms with sheriff courts since the reform of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973. Appeals from the Court of Session are made to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, which is also the final authority for constitutional affairs.

The head of state in Scotland is the British monarch, currently Queen Elizabeth II (since 1952). The Kingdom of Scotland entered a fiscal and political union with the Kingdom of England with the Acts of Union 1707, by which the Parliament of Scotland was abolished along with its English counterpart to form the Parliament of Great Britain, and from that time Scotland has been represented by members of the House of Commons in the Palace of Westminster. The Scottish Parliament was established in 1999, as a result of the Scotland Act 1998 and the preceding 1997 Scottish devolution referendum, held under the Referendums (Scotland and Wales) Act 1997.

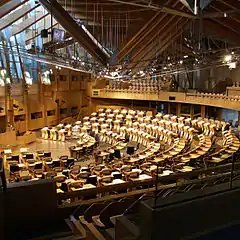

The Scottish Parliament sits in the Scottish Parliament Building at Holyrood in Edinburgh, the Scottish capital. For the purposes of local government in Scotland, the country has been divided into 32 council areas since the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994. Since the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973, which also abolished the shires of Scotland, the country has been subdivided into community councils. Though retained for statistical purposes, the civil parishes in Scotland were abolished for administrative purposes in the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1929.

The issues of Scottish nationalism and Scottish independence are prominent political issues in the early 21st century. When the Scottish National Party formed a majority government after the 2011 Scottish Parliament election and passed the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013, the British parliament concluded the Edinburgh Agreement with the Scottish Government, enabling the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. The referendum was held on 18 September 2014, with 55.3% voting to stay in the United Kingdom and 44.7% voting for independence.

Constitution

Elected in the 2016 Scottish Parliament election, the centre-left pro-independence Scottish National Party is the party which forms the devolved government; it currently holds a plurality of seats in the parliament (61 out of 129). The first minister is conventionally the leader of the political party with the most support in the Scottish Parliament, currently Nicola Sturgeon MSP. Opposition parties include the Scottish Conservatives (centre-right, conservative), Scottish Labour Party (centre-left, social democratic), the Scottish Liberal Democrats (centrist, social liberal), and the Scottish Green Party (centre-left to left-wing, green). Elections are held once every five years, with 73 Members being elected to represent constituencies, and the remaining 56 elected via a system of proportional representation. At Westminster, Scotland is represented by 47 MPs from the Scottish National Party, 6 from the Conservative Party, 1 from the Labour Party and 4 from the Liberal Democrats elected in the 2019 United Kingdom general election. The Secretary of State for Scotland, currently Alister Jack MP, a Scottish Conservative, is usually a member of the House of Commons representing a constituency in Scotland.

The party with the largest number of seats in the Scottish Parliament is the Scottish National Party (SNP), which campaigns for Scottish independence. The current first minister of Scotland is SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon, who has led a government since November 2014. The previous first minister, Alex Salmond, led the SNP to an overall majority victory in the May 2011 general election, which was then lost in 2016 and now forms a minority government. Other parties represented in the parliament are the Labour Party, Conservative Party which form the official opposition, Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Green Party. The next Scottish Parliament election is due to be held in May 2021.

Under devolution, Scotland is represented by 59 MPs in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom elected from territory-based Scottish constituencies, out of a total of 650 MPs in the House of Commons. Various members of the House of Lords represent Scottish political parties. A Secretary of State for Scotland, who prior to devolution headed the system of government in Scotland, sits in the Cabinet of the United Kingdom and is responsible for the limited number of powers the office retains since devolution, as well as relations with other Whitehall Ministers who have power over reserved matters. The Scottish Parliament can refer devolved matters back to Westminster to be considered as part of United Kingdom-wide legislation by passing a Legislative Consent Motion — usually referred to as a Sewel Motion. This has been done on a number of occasions where it has been seen as either more efficient, or more politically expedient to have the legislation considered by Westminster. The Scotland Office is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for reserved Scottish affairs. The Scotland Office, created in 1999, liaises with other Whitehall departments about devolution matters. Before devolution and the Scotland Office, much of the role of the devolved Scottish Government was undertaken by the Scottish Office, the previous British ministerial department led by Scottish Secretary.

The main political debate in Scotland tends to revolve around attitudes to the constitutional question. Under the pressure of growing support for Scottish independence, a policy of devolution had been advocated by all three GB-wide parties to some degree during their history (although Labour and the Conservatives have also at times opposed it). This question dominated the Scottish political scene in the latter half of the twentieth century with Labour leader John Smith describing the revival of a Scottish parliament as the "settled will of the Scottish people".[1]

Since devolution, the main argument about Scotland's constitutional status is over whether the Scottish Parliament should accrue additional powers (for example over fiscal policy), or seek to obtain full independence. Ultimately the long term question is: should the Scottish parliament continue to be a subsidiary assembly created and potentially abolished by the constitutionally dominant and sovereign parliament of the United Kingdom (as in devolution) or should it have an independent existence as of right, with full sovereign powers (either through independence, a federal United Kingdom or a confederal arrangement)? To clarify these issues, the SNP-led Scottish Government published Choosing Scotland's Future, a consultation document directed to the electorate under the National Conversation exercise.

The programmes of legislation enacted by the Scottish Parliament have seen the divergence in the provision of public services compared to the rest of the United Kingdom.[2] While the costs of a university education, and care services for the elderly are free at point of use in Scotland, fees are paid in the rest of the UK. Scotland was the first country in the UK to ban smoking in public places, with the ban effective from 26 March 2006.[3] Also, on 19 October 2017, the Scottish government announced that smacking children as punishment was to be banned in Scotland, the first nation of the UK to do so.

In a further divergence from the rest of the United Kingdom from 1 January 2021 all devolved Scottish legislation will be legally required to keep in regulatory alignment with future European Union law following the end of the Brexit transition period which ends on 31 December 2020 after the Scottish Parliament passed the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2020 despite the United Kingdom no longer being a EU member state.[4]

Scottish Parliament

The election of an Labour government in the 1997 United Kingdom general election was followed by the Referendums (Scotland and Wales) Act 1997, which legislated for the 1997 Scottish devolution referendum, a referendum on establishing a devolved Scottish Parliament. 74.3% of voters agreed with the establishment of the Parliament and 63.5% agreed it should have tax-varying powers, which meant that it could adjust income taxes by up to 3%.[5][6]

The Scottish Parliament was then created by the Scotland Act 1998 of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (Westminster Parliament). This act of parliament sets out the subjects to be dealt with at Westminster, referred to as reserved matters, including defence, international relations, fiscal and economic policy, drugs law and broadcasting. Anything not mentioned as a specific reserved matter is automatically devolved to Scotland, including health, education, local government, Scots law and all other issues. This is one of the key differences between the successful Scotland Act 1998 and the failed Scotland Act 1978. The powers of the Scottish Parliament were further increased by the British Parliament's Scotland Act 2012 and Scotland Act 2016.

The Parliament is elected by a mixture of the first past the post and proportional representation electoral systems, namely, the additional members system. Thus the Parliament is unlike the Westminster Parliament, which is elected solely by the first past the post method. The Scottish Parliament is elected every five years and has 129 members, referred to as members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs). Of the 129 MSPs, 73 are elected to represent first past the post constituencies, whilst the remaining 56 are elected by the additional member system.

The proportional representation system has resulted in the election of a number of candidates from parties that would not have been expected to get representation through the first past the post system.

A devolved government called the Scottish Executive (renamed Scottish Government in 2007) was established along with the Scottish Parliament in 1999, with the first minister of Scotland at its head. The secretariat of the Executive is part of the UK Civil Service and the head of the Executive, the permanent secretary (presently Leslie Evans), is the equivalent of the permanent secretary of a Whitehall department. As a result of devolution of powers to the Holyrood government, the Whitehall Scottish Office was reduced and reformed into the Scotland Office.

First ministers

|

Presiding officers

|

Parliament of the United Kingdom

| Year | Con | Lab | SNP | Lib Dem[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 6 seats 25.1% | 1 seat 18.6% | 48 seats 45.0% | 4 seats 9.5% |

| 2017 | 13 seats 28.6% | 7 seats 27.1% | 35 seats 36.9% | 4 seats 6.8% |

| 2015 | 1 seat 14.9% | 1 seat 24.3% | 56 seats 50.0% | 1 seat 7.5% |

| 2010 | 1 seat 16.7% | 41 seats 42.0% | 6 seats 19.9% | 11 seats 18.9% |

| 2005 | 1 seat 15.8% | 41 seats 39.5% | 6 seats 17.7% | 11 seats 22.6% |

| 2001 | 1 seat 15.6% | 56 seats 43.9% | 5 seats 20.1% | 10 seats 16.4% |

| 1997 | 0 seats 17.5% | 56 seats 41.0% | 6 seats 22.0% | 10 seats 13.0% |

| 1992 | 11 seats 25.7% | 49 seats 34.4% | 3 seats 21.5% | 9 seats 13.1% |

| 1987 | 10 seats 24.0% | 50 seats 38.7% | 3 seats 14.0% | 9 seats 19.3% |

| 1983 | 21 seats 28.4% | 40 seats 33.2% | 2 seats 11.8% | 8 seats 24.5% |

| 1979 | 22 seats 31.4% | 44 seats 38.6% | 2 seats 17.3% | 3 seats 9.0% |

| Oct 1974 | 16 seats 24.7% | 41 seats 33.1% | 11 seats 30.4% | 3 seats 8.3% |

| Feb 1974 | 21 seats 32.9% | 40 seats 34.6% | 7 seats 21.9% | 3 seats 7.9% |

| 1970 | 23 seats 38.0% | 44 seats 44.5% | 1 seat 11.4% | 3 seats 5.5% |

| 1966 | 20 seats 37.6% | 46 seats 47.7% | 0 seats 5.0% | 5 seats 6.7% |

| 1964 | 24 seats 37.3% | 43 seats 46.9% | 0 seats 2.4% | 4 seats 7.6% |

| 1959 | 31 seats 47.3% | 38 seats 46.7% | 0 seats 0.8% | 1 seat 4.8% |

| 1955 | 36 seats 50.1% | 34 seats 46.7% | 0 seats 0.5% | 1 seat 1.9% |

| 1951 | 35 seats 48.6% | 35 seats 48.0% | 0 seats 0.3% | 1 seat 2.8% |

House of Commons

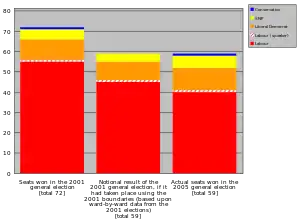

Until the 2005 general election, Scotland elected 72 MPs from 72 single-member constituencies to serve in the House of Commons. As this over-represented Scotland in comparison to the other parts of the UK, Clause 81 of the Scotland Act 1998 equalised the English and Scottish electoral quota. As a result, the Boundary Commission for Scotland's recommendations were adopted, reducing Scottish representation in the House of Commons to 59 MPs with effect from the 2005 general election. The necessary amendment to the Scotland Act 1998, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom as the Scottish Parliament (Constituencies) Act 2004. The previous over-representation was widely accepted before to allow for a greater Scottish voice in the Commons, but since the establishment of a Scottish Parliament it has been felt that this is not necessary.

Since the 1880s the British Government in Scotland has been represented in parliament by the Secretary of State for Scotland, a parliamentary secretary of state and a cabinet minister in the Cabinet of the United Kingdom and usually a member of the House of Commons.

Current Scottish representation in the Commons is :

House of Lords

In 2015, twelve of the 92 hereditary peers with seats in the House of Lords to which they are elected (from among themselves) under the House of Lords Act 1999 were registered as living in Scotland, as were 49 life peers appointed under the Life Peerages Act 1958, including five former Lords Advocate.[7] James Thorne Erskine, 14th Earl of Mar and 16th Earl of Kellie, retired in 2017 having lost his seat as a hereditary peer in 1999 but regained it in 2000 as a life peer; Charles Lyell, 3rd Baron Lyell (former Under-Secretary of State for Northern Ireland) died the same year. One of the former Lords Advocate, Kenneth Cameron, Baron Cameron of Lochbroom, retired from the Lords in 2016, while another, Donald Mackay, Baron Mackay of Drumadoon died in 2018. Besides these 61 peers listed in 2015 are hereditary members of the Lords living outwith Scotland, but who have titles in the Peerage of Scotland, such as Margaret of Mar, 31st Countess of Mar, or Scottish titles in the peerages of Great Britain or of the United Kingdom.[7] Apart from these, there are also Scottish life peers with titles associated with places outside Scotland, such as Michelle Mone, Baroness Mone of Mayfair.[7]

Political appointees include:

Former Lords Advocate include:[7]

|

|

Scottish hereditary peers include:

|

|

Between the Acts of Union 1707 and the Peerage Act 1963, peers with titles in the Peerage of Scotland were entitled to elect sixteen representative peers to the House of Lords. Between the 1963 Act and the House of Lords Act 1999 the entire hereditary Peerage of Scotland was entitled to sit in the House of Lords, alongside those with titles in the peerages of England, of Ireland, of Great Britain, and of the UK.

Local government

Local government in Scotland is organised into 32 unitary authorities. Each local authority is governed by a council consisting of elected councillors, who are elected every five years by registered voters in each of the council areas.

Scottish councils co-operate through, and are represented collectively by, the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA).

There are currently 1,227 councillors in total, each paid a part-time salary for the undertaking of their duties. Each authority elects a Convener or Provost to chair meetings of the authority's council and act as a figurehead for the area. The four main cities of Scotland, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Dundee have a Lord Provost who is also, ex officio, Lord Lieutenant for that city.

There are in total 32 councils, the largest being the Glasgow City Council with more than 600,000 inhabitants, the smallest, Orkney Islands Council, with fewer than 20,000 people. See Subdivisions of Scotland for a list of the council areas.

Community councils

Community councils represent the interests of local people. Local authorities have a statutory duty to consult community councils on planning, development and other issues directly affecting that local community. However, the community council has no direct say in the delivery of services. In many areas they do not function at all, but some work very effectively at improving their local area.[8]

History

Until 1832 Scottish politics remained very much in the control of landowners in the country, and of small cliques of merchants in the burghs. Agitation against this position through the Friends of the People Society in the 1790s met with Lord Braxfield's explicit repression on behalf of the landed interests.[9] The Scottish Reform Act 1832 rearranged the constituencies and increased the electorate from under 5,000 to 65,000.[10] The Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868 extended the electorate to 232,000 but with "residential qualifications peculiar to Scotland".[11] However, by 1885 around 50% of the male population had the vote, the secret ballot had become established, and the modern political era had started.

From 1885 to 1918 the Liberal Party almost totally dominated Scottish politics. Only in the general election of 1955 and the general election of 1931 did the Unionist Party, together with their National Liberal and Liberal Unionist allies, win a majority of votes.

After the coupon election of 1918, 1922 saw the emergence of the Labour Party as a major force. Red Clydeside elected a number of Labour MPs. A communist was elected for Motherwell in 1924, but in essence the 1920s saw a 3-way fight between Labour, the Liberals and the Unionists. The National Party of Scotland first contested a seat in 1929. It merged with the centre-right Scottish Party in 1934 to form the Scottish National Party, but the SNP remained a peripheral force until the watershed Hamilton by-election of 1967.

The Communists won West Fife in 1935 and again in 1945 (Willie Gallacher) and several Glasgow Labour MPs joined the Independent Labour Party in the 1930s, often heavily defeating the official Labour candidates.

The National Government won the vast majority of Scottish seats in 1931 and 1935: the Liberal Party, banished to the Highlands and Islands, no longer functioned as a significant force in central Scotland.

In 1945, the SNP saw its first MP (Robert McIntyre) elected at the Motherwell by-election, but had little success during the following decade. The ILP members rejoined the Labour Party, and Scotland now had in effect a two-party system.

- 1950: The Liberals won two seats - Jo Grimond winning Orkney and Shetland.

- 1951: Labour and the Unionists won 35 seats each, the Liberals losing one seat.

- 1955: The Unionists won a majority of both seats and votes. The SNP came second in Perth and Kinross.

- 1959: In contrast to England, Scotland swung to Labour, which scored four gains at the expense of the Unionists. This marked the start of a trend which in less than 40 years saw the Unionists' Scottish representation at Westminster reduced to zero. This was the last occasion when the Unionists won in Scotland: their merger with the Conservative Party of England and Wales in 1965, to become the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party, began a long, steady decline in their support.

- 1964: There was a substantial swing to Labour, giving them 44 of Scotland's 71 seats. The Liberals won four seats, all in the Highlands.

- 1965: David Steel won the Roxburgh, Selkirk and Peebles by-election for the Liberals.

- 1966: Labour gained 2 more seats and the Liberals made a net gain of 1. The SNP garnered over 100,000 votes and finished second in 3 seats.

- 1967: The SNP did well in the Glasgow Pollok by-election, but this allowed the Conservative and Unionist candidate to win. However, in the subsequent Hamilton by-election Winnie Ewing won a sensational victory.

- 1968: The SNP made substantial gains in local elections.

- 1970: The SNP performed poorly in local elections and in the Ayrshire South by-election. The general election saw a small swing to the Conservatives & Unionists, but Labour won a majority of seats in Scotland. The SNP made little progress in central Scotland, but took votes from the Liberals in the Highlands and in north east Scotland, and won the Western Isles.

- 1971-1973: The SNP did well in by-elections, Margo MacDonald winning Glasgow Govan.

- 1974: In the two general elections of 1974 (in February and October) the SNP won 7 and then 11 seats, their share of the vote rising from 11% in 1970 to 22% and then 30%. With the Labour Party winning the October election by a narrow margin, the SNP appeared in a strong position.

Inverness Town House, a local government building in Inverness, the major town of the Highland council area, governed by The Highland Council

Inverness Town House, a local government building in Inverness, the major town of the Highland council area, governed by The Highland Council - 1974-1979: Devolution dominated this period: the Labour government attempted to steer through devolution legislation, based on the recommendations of the Kilbrandon Commission, against strong opposition, not least from its own backbenchers. Finally a referendum, whilst producing a small majority in favour of an elected Scottish Assembly, failed to achieve a turnout of 40% of the total electorate, a condition set in the legislation. In the 1979 general election the SNP fared poorly, falling to 17% of the vote and 2 seats. Labour did well in Scotland, but in the United Kingdom as a whole Margaret Thatcher led the Conservatives to a decisive victory.

- 1979-1983: The SNP suffered severe splits as the result of the 1979 drop in support. Labour also was riven by internal strife as the Social Democratic Party split away. Despite this, the 1983 election still saw Labour remain the majority party in Scotland, with a smaller swing to the Conservatives than in England. The SNP's vote declined further, to 12%, although it won two seats.

- 1987: The Labour Party did well in the 1987 election, mainly at the expense of the Conservatives & Unionists, who were reduced to their smallest number of Scottish seats since before World War I. The SNP made a small but significant advance.

- 1988: Jim Sillars won the Glasgow Govan by-election for the SNP.

- 1992: This election proved a disappointment for Labour and the SNP in Scotland. The SNP went from 14% to 21% of the vote but won only 3 seats. The Conservative and Unionist vote did not collapse, as had been widely predicted, leading to claims that their resolutely anti-devolution stance had paid dividends.

- 1997: In common with England, there was a Labour landslide in Scotland. The SNP doubled their number of MPs to 6, but the Conservatives & Unionists failed to win a single seat. Unlike 1979, Scottish voters delivered a decisive "Yes" vote in the referendum on establishing a Scottish Parliament.

- 1999: The Scottish Parliament was established. A coalition of Labour and Liberal Democrats led by Donald Dewar took power.

Headquarters of the Scotland Office in Edinburgh's New Town

Headquarters of the Scotland Office in Edinburgh's New Town - 2007: The SNP became Scotland's largest party in the 2007 Scottish Parliament election and formed a minority government.

- 2008: John Mason won the Glasgow East by-election for the SNP.

- 2008: Lindsay Roy won the Glenrothes by-election for Labour with an increased share of the vote and a 6,737 majority over the SNP.

- 2009: Willie Bain won the Glasgow North East by-election for Labour with 59.4% of the vote and an 8,111 majority over the SNP.

- 2010: 2010 United Kingdom general election: Labour won 41 out of 59 Scottish seats including Glasgow East from the SNP and received over 1 million votes across Scotland, despite losing 91 seats across Britain as a whole.

- 2011: The SNP become the first party to win an overall majority in the Scottish Parliament.

- 2015: The SNP won 56 out of 59 Scottish seats, winning 50% of the popular vote. Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats won 1 seat each.

- 2017: In the June snap Westminster general election, the SNP won 35 out of the 59 Scottish seats, the Conservatives won 13, Labour won 7 and the Liberal Democrats won 4 seats.

- 2019: In the Westminster general election of 2019, the SNP won 48 out of the 59 Scottish seats, the Conservatives won 6, the Liberal Democrats won 4 and Labour won 1.

Political parties

.jpeg.webp)

The current party forming the Scottish Government is the Scottish National Party (SNP), which won 63 of 129 seats available in the 2016 Scottish Parliament election. The SNP was formed in 1934 with the aim of achieving Scottish independence. They are broadly centre-left and are in the European social-democratic mould. They are the largest party in the Scottish Parliament and have formed the Scottish Government since the 2007 Scottish Parliament election.

In the course of the twentieth century, Scottish Labour rose to prominence as Scotland's main political force. The party was established to represent the interests of workers and trade unionists. From 1999 to 2007, they operated as the senior partners in a coalition Scottish Executive. They lost power in 2007 when the SNP won a plurality of seats and entered a period of dramatic decline,[12] losing all but one of their seats in the 2015 UK election and falling to third place in the 2016 Scottish election. The 2017 UK election produced a mixed result for the party as it gained six seat and increased its vote by 2.8% but the party came in third behind the SNP and Scottish Conservatives.

The Scottish Liberal Democrats were the junior partners in the 1999 to 2007 coalition Scottish Executive. The party has lost much of its electoral presence in Scotland since the UK Liberal Democrats entered into a coalition government with the UK Conservative Party in 2010. In the 2015 UK election they were reduced from 12 seats to one seat, and since the 2016 Scottish Parliament election they have had the fifth highest number of MSPs (five), unchanged on 2011.

The Unionist Party was the only party ever to have achieved an outright majority of Scottish votes at any general election, in 1951 (they only won a majority if the votes if their National Liberal and Liberal Unionist allies are included). The Unionist Party was allied with the UK Conservative Party until 1965, when the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party was formed. The Conservatives then entered a long-term decline in Scotland, culminating in their failure to win any Scottish seats in the 1997 UK election. At the four subsequent UK elections (2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015) the Conservatives won only one Scottish seat. The party enjoyed a revival of fortunes in the 2016 Scottish Parliament election, winning 31 seats and finishing in second place. The Conservatives are a centre-right party.

The Scottish Green Party have won regional additional member seats in every Scottish Parliament election, as a result of the proportional representation electoral system. They won one MSP in 1999, increased their total to seven at the 2003 election but saw this drop back to 2 at the 2007 election. They retained two seats at the 2011 election, then increased this total to six in the 2016 election. The Greens support Scottish independence.

See also

Notes

- From the 1951 election to the 1979 election the Party was just the Liberal Party, within the 1983 and 1987 election the party was the SDP-Liberal Alliance.

References

- Cavanagh, Michael (2001) The Campaigns for a Scottish Parliament. University of Strathclyde. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- "Devolved services in Scotland Archived 18 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine" direct.gov.uk Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- Scotland begins pub smoking ban, BBC News Online, 26 March 2006

- "MSPs pass Brexit bill to 'keep pace' with EU laws". BBC News. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- "London Offers Scotland Its Own Parliament, With Wide Powers". The New York Times. 25 July 1997. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "Past Referendums - Scotland 1997". The Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- Campsie, Alison (11 November 2015). "The Scottish peers, who they are, why they are there - and what they do". The Scotsman. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Stirling Council. "Community Council Info". Stirling Council Homepage. Stirling Council. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- Buchan, James (2003). Crowded with Genius. Harper Collins. p. 338. ISBN 0-06-055888-1.

- Lynch, Michael (1992). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico. p. 391. ISBN 0-7126-9893-0.

- Lynch (1992), p416

- Harvey, Malcolm (2018). "Scotland: devolved government and national politics". The UK's Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit. LSE Press. doi:10.31389/book1.t. ISBN 978-1-909890-44-2.

External links

- Text of the Scotland Act 1998 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.