Porthmadog

Porthmadog (/pɔːrθˈmædɒɡ/; Welsh: [pɔrθˈmadɔɡ] (![]() listen)), known before 1974 in its anglicised Portmadoc form and locally as "Port",[1] is a Welsh coastal town and community in the Eifionydd area of Gwynedd. Before 1974 it was in the historic county of Caernarfonshire. It lies 5 miles (8 km) east of Criccieth, 11 miles (18 km) south-west of Blaenau Ffestiniog, 25 miles (40 km) north of Dolgellau and 20 miles (32 km) south of Caernarfon. The community population was 4,185 in the 2011 census and an estimated 4,134 in 2019.[2] It developed in the 19th century as a port for slate sent to England and elsewhere, but as the industry declined, it continued as a shopping centre and tourist destination, being close to Snowdonia National Park and the Ffestiniog Railway.[3] The 1987 National Eisteddfod was held there.[4] It includes the nearby villages of Borth-y-Gest, Morfa Bychan and Tremadog.[5]

listen)), known before 1974 in its anglicised Portmadoc form and locally as "Port",[1] is a Welsh coastal town and community in the Eifionydd area of Gwynedd. Before 1974 it was in the historic county of Caernarfonshire. It lies 5 miles (8 km) east of Criccieth, 11 miles (18 km) south-west of Blaenau Ffestiniog, 25 miles (40 km) north of Dolgellau and 20 miles (32 km) south of Caernarfon. The community population was 4,185 in the 2011 census and an estimated 4,134 in 2019.[2] It developed in the 19th century as a port for slate sent to England and elsewhere, but as the industry declined, it continued as a shopping centre and tourist destination, being close to Snowdonia National Park and the Ffestiniog Railway.[3] The 1987 National Eisteddfod was held there.[4] It includes the nearby villages of Borth-y-Gest, Morfa Bychan and Tremadog.[5]

| Porthmadog | |

|---|---|

Porthmadog Harbour was developed to export slate | |

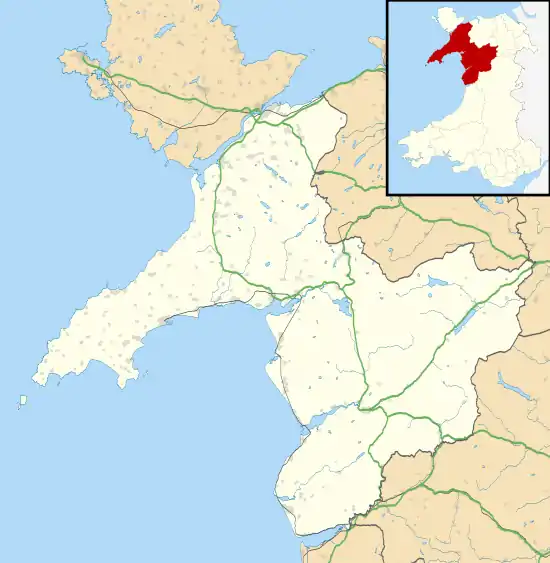

Porthmadog Location within Gwynedd | |

| Area | 16.18 km2 (6.25 sq mi) |

| Population | 4,185 (2011) |

| • Density | 259/km2 (670/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SH565385 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | PORTHMADOG |

| Postcode district | LL49 |

| Dialling code | 01766 |

| Police | North Wales |

| Fire | North Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament | |

History

Porthmadog came about after William Madocks built a sea wall, the Cob, in 1808–1811 to reclaim much of Traeth Mawr from the sea for farming use. Diversion of the Afon Glaslyn caused it to scour out a new natural harbour deep enough for small ocean-going sailing ships,[6] and the first public wharves appeared in 1825. Quarry companies followed, with wharves along the shore almost to Borth-y-Gest, while slate was carted from Ffestiniog down to quays along the Afon Dwyryd, then boated to Porthmadog for transfer to seagoing vessels.[7]

In the later 19th-century, Porthmadog flourished as a port, its population rising from 885 in 1821 to over 3,000 by 1861. The rapidly growing cities of England needed high-quality roofing slate, which was brought to the new port by tramway from quarries in Ffestiniog and Llanfrothen.[6] The Ffestiniog Railway opened in 1836, followed by the Croesor Tramway in 1864 and the Gorseddau Tramway in 1856. By 1873 over 116,000 tons (117,800 t) were exported through Porthmadog in over a thousand ships.[8] Several shipbuilders were active at this time. They were known particularly for their three-masted schooners called Western Ocean Yachts, the last of which was launched in 1913.[6]

By 1841 the trackway across the reclaimed land had been straightened. It would develop into as Stryd Fawr, the main commercial street of the town, with a range of shops and public houses and a post office, but the open green retained. A mineral railway to Tremadog ran along what would become Heol Madog. To the north was an industrial area of foundries, timber saw mills, slate works, a flour mill, a soda-pop plant and gasworks.[7]

Porthmadog's role as a commercial port, already reduced by the opening of the Aberystwith and Welsh Coast Railway in 1867, was effectively ended by the First World War, when the lucrative German market for slate collapsed. The 19th-century wharves survive, but the slate warehouses have been replaced by holiday apartments and the harbour is used by leisure yachts.[6]

Etymology

The name "Porthmadog" is derived from its English spelling, 'Portmadog' (this was the official name until 1974).[1] This was derived as a portmanteau of Port and Madocks,[9] although there is a belief that it is named after a folklore character, Madog ab Owain Gwynedd, whose name appears also in "Ynys Fadog" ("Madog Island").[1]

The earliest written references to the name "Port Madoc" are from the 1830s, coinciding with the opening of the Ffestiniog Railway and the town's subsequent growth. The first Ordnance Survey map to use the name appeared in 1838.[10]

Governance

Ynyscynhaiarn was a civil parish in the cantref of Eifionydd. In 1858 a local board of health was established under the Public Health Act 1848,[11] and from 1889 this formed a second tier of local government in Caernarfonshire. Under the Local Government Act 1894 the local board became an urban district, which by 1902 had changed its name to Portmadoc.[12] In 1934 part of the area was transferred to Dolbenmaen and a smaller area was taken in from Treflys, which was abolished.[13] Porthmadog Urban District was abolished in 1974, when it became part of Dwyfor District in the new county of Gwynedd, though it retained limited powers as a community. Dwyfor itself was abolished when Gwynedd became a unitary authority in 1996.[14]

The town now forms three divisions of Cyngor Gwynedd, each with one councillor. In 2012 Jason Humphreys, for Llais Gwynedd, was elected in Porthmadog East.[15] Selwyn Griffiths (Plaid Cymru) retained his seat in Porthmadog West unopposed.[16] Tremadog is included in the Porthmadog-Tremadog division with Beddgelert and part of Dolbenmaen.[17] In 2012 Alwyn Gruffydd for Llais Gwynedd retained the seat.[18]

Porthmadog Town Council has 16 elected members. In 2008, 12 of its councillors were elected unopposed: seven Independents, four Plaid Cymru and one Llais Gwynedd. There were four unfilled seats. The town divides into six wards: Gest, Morfa Bychan, East, West, Tremadog and Ynys Galch.[19][20]

From 1950 to 2010, Porthmadog was part of Caernarfon parliamentary constituency, represented since 2001 by Hywel Williams (Plaid Cymru). In 2010 the town became part of the Dwyfor Meirionnydd constituency. In the Senedd, it has since 2007 formed part of Dwyfor-Meirionnydd constituency, represented by Dafydd Elis-Thomas.[21] It forms part of the electoral region of Mid and West Wales.[22]

Geography

Porthmadog lies in Eifionydd, on the estuary of the Afon Glaslyn, where it runs into Tremadog Bay. The estuary, filled with sediment deposited by rivers emptying from the melting glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age,[23] is a haven for migrating birds. Oystercatchers, redshanks and curlews are common, as are summer flocks of sandwich terns.[24] To the west looms Moel y Gest, rising 863 feet (263 m) above the town as a Marilyn.[3]

The town's temperate maritime climate is influenced by the Gulf Stream.

| Month | Average high | Average low | Average precipitation |

| January | 8.0 °C | 3.0 °C | 8.38 cm |

| February | 8.0 °C | 3.0 °C | 5.59 cm |

| March | 9.0 °C | 4.0 °C | 6.60 cm |

| April | 11.0 °C | 5.0 °C | 5.33 cm |

| May | 14.0 °C | 8.0 °C | 4.83 cm |

| June | 17.0 °C | 10.0 °C | 5.33 cm |

| July | 18.0 °C | 12.0 °C | 5.33 cm |

| August | 19.0 °C | 12.0 °C | 7.37 cm |

| September | 17.0 °C | 11.0 °C | 7.37 cm |

| October | 14.0 °C | 9.0 °C | 9.14 cm |

| November | 11.0 °C | 6.0 °C | 9.91 cm |

| December | 9.0 °C | 4.0 °C | 9.40 cm |

| Climate data for Porthmadog, Wales, United Kingdom | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

8 (46) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

14 (57) |

17 (63) |

18 (64) |

19 (66) |

17 (63) |

14 (57) |

11 (52) |

9 (48) |

13 (55) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6 (43) |

6 (43) |

7 (45) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

14 (57) |

15 (59) |

16 (61) |

14 (57) |

12 (54) |

9 (48) |

7 (45) |

10 (51) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3 (37) |

3 (37) |

4 (39) |

5 (41) |

8 (46) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

11 (52) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

7 (45) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 83.8 (3.30) |

55.9 (2.20) |

66.0 (2.60) |

53.3 (2.10) |

48.3 (1.90) |

53.3 (2.10) |

53.3 (2.10) |

73.7 (2.90) |

73.7 (2.90) |

91.4 (3.60) |

99.1 (3.90) |

94.0 (3.70) |

845.8 (33.3) |

Borth-y-Gest

Borth-y-Gest, 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Porthmadog, is built in a shallow bowl sweeping down to a sheltered bay, with hidden sandy coves and cliffs. Ships were built here before Porthmadog was established and houses, still known as "pilot houses", were erected at the mouth of the harbour so that pilots could watch for ships needing them.[26] The village and its rows of Victorian houses have retained much of its atmosphere and charm. Stryd Mersey leads up from the bay, flanked by terraced cottages.[24]

Before Porthmadog was developed, this was the starting point of a major crossing over the wide and dangerous Glaslyn estuary. Locals earned money by guiding travellers across the treacherous sands of Traeth Mawr to Harlech.[27]

Parc y Borth is a local nature reserve in deciduous woodland dominated by ancient Welsh oaks. Green woodpeckers, tawny owls and pied flycatchers can be seen among the branches.[28]

On the shore is another nature reserve, Pen y Banc, a mixture of coastal rocks, secluded sandy coves and mixed woodland. Established in 1996, it is a good spot to see wading birds. Its beaches attract many visitors. The mild climate results in a wide variety of vegetation, from gorse and heather through to blackthorn, crab apple, and birch.[29]

Morfa Bychan

Morfa Bychan, 2.1 miles (3.4 km) south-west of Porthmadog, has a wide beach, Black Rock Sands (Welsh: Traeth Morfa Bychan),[30] with Graig Ddu, a rocky headland, at its western end. At low tide, rock pools and caverns are exposed.[31] The beach is popular with windsurfers,[32] and is unusual in allowing vehicles onto the sands.[33]

Sand dunes behind the beach form part of Morfa Bychan and Greenacres Nature Reserve.[34] Standing in a field is Cist Cerrig, a dolmen,[35] near which are rocks containing cup marks.[36]

In 1996 there were protests backed by Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg against the building of 800 houses at Morfa Bychan.[37] These followed a High Court decision that planning permission granted in 1964 remained valid. The owners of the site later entered a legal agreement with Cyngor Gwynedd, allowing a caravan site and nature reserve to be placed on part of the site, which ensured that the 1964 permit could no longer be implemented. The council also settled a compensation claim by developers for the way the matter had been handled.[38]

Tremadog

Tremadog, an example of a planned settlement, is 0.9 miles (1.4 km) north of Porthmadog. The village was built on land reclaimed from Traeth Mawr by William Madocks. In 1805 the first cottages appeared in what Madocks called Pentre Gwaelod ("Bottom Village"), which was designed to create the impression of a borough, with a Town Hall and Dancing Room at its centre. Industry was also included in the plan, with a Manufactory, Loomery, fulling mill and corn mill, all worked by water power.[39]

To the north of the village is Tan-yr-Allt, a property bought by Madocks in 1798 and used by him for the first Regency house in Gwynedd. The sloping garden consists mainly of lawns planted with trees and shrubs. It includes a memorial to Percy Bysshe Shelley.[40]

Demography

At the 2001 census, Porthmadog had a population of 4,187,[41] of whom 18.2 per cent were below the age of 16 and 23.6 per cent were over 65 years of age; 69.5 per cent of households were in owner-occupied accommodation and 24.6 per cent were renting. Holiday homes accounted for 12.5 per cent of dwellings.[42]

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 |

| Population | 525 | 889 | 885 | 1,075 | 1,888 | 2,347 | 3,138 | 4,367 | 5,506 |

| Year | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 2001 |

| Population | 5,224 | 4,883 | 4,445 | 4,184 | 3,986 | 4,618 | 4,061 | 3,960 | 4,187 |

Economy

At the 2001 census, 44.3 per cent of the working-age population were employed, 11.5 per cent self-employed, 5.3 per cent unemployed and 20.4 per cent retired. Of the employed, 33.0 per cent worked in the distribution, hotel and catering trades and 23.5 per cent in public administration, education and health.[42]

Porthmadog expanded rapidly as a slate-exporting port. Welsh slate was in high demand as a construction material in the English industrial cities and transported to the new port by horse-drawn tramways. The Ffestiniog Railway, opened in 1836 as a gravity railway with horses hauling empty slate waggons back up to the quarries, was converted to steam operation in 1863; trains ran straight onto the wharves. By 1873 116,000 tons (117,800 t) of slate were being shipped out of Porthmadog and other trade developed. The Carnarvonshire and Merionethshire Steamship Company formed in 1864 purchased the Rebecca to carry stores from Liverpool to supply the growing town.[48] The First World War marked the end of Porthmadog's exports. No new ships were built, several were sunk by enemy action, and most of the survivors were sold. The arrival at Blaenau Ffestiniog of the LNWR in 1879 and the GWR in 1883 brought a steady decline in the slate traffic carried by the Festiniog Railway and Portmadoc shipping. Some slate had been carried via the Festiniog Railway, the Croesor & Portmadoc Railway and the Cambrian Railways after the latter's line had been opened between Barmouth and Pwllheli in 1867; this traffic was diverted to the exchange yard established between the Festiniog Railway and the Cambrian Railways at Minffordd in 1872.[49] By 1925 less than five per cent of Ffestiniog's slate output went out by sea. The final load of slate delivered by rail left by sea from Porthmadog in 1946. Two months later the railway ceased commercial operations.[50]

Before construction of the Cob in 1812, ships had been built at locations round Traeth Mawr. As the town developed, several shipbuilders from the Meirionnydd side moved to the new port, building brigs, schooners, barquentines and brigantines. After the arrival of the railway there was a reduction in trade, but a new type of ship, the Western Ocean Yacht, was developed for the salt cod industry in Newfoundland and Labrador. Shipbuilding came to an end in 1913, the last vessel built being the Gestiana, which was lost on its maiden voyage.[50]

In the 19th-century Porthmadog had at least three iron foundries. The Glaslyn Foundry opened in 1848, and the Union Iron Works in 1869. The Britannia Foundry, opposite Porthmadog Harbour Railway Station appeared in 1851 and grew rapidly with the town's prosperity. It supplied slate-working machinery and railway equipment to all but one of the slate quarries operating in England and Wales. A lucrative sideline was the production of drains and manhole covers for Caernarfonshire's roads.[51]

Culture

Porthmadog is a mainly Welsh-speaking community: 74.9 per cent of the population speak it regularly.[42] The highest proportion of Welsh speakers is in the 10–14 age range, at 96.3 per cent. Almost all community activities are held in Welsh. Porthmadog hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1987.[4]

Y Ganolfan on Stryd Fawr, built in 1975, is a venue for concerts, exhibitions and other community events. It has also hosted televised wrestling matches.[52]

Porthmadog Maritime Museum on Oakley Wharf occupies an old slate shed. It has displays about schooners built in the town and the men who sailed in them.[53]

Landmarks

The Cob is a prominent embankment built across the Glaslyn estuary in 1811 by William Madocks to reclaim land at Traeth Mawr for agriculture. It opened with a four-day feast and Eisteddfod celebrating the roadway connecting Caernarfonshire to Meirionnydd, which figured in Madocks's plans for a road from London to his proposed port at Porthdinllaen. Three weeks later, the embankment was breached by high tides and Madocks's supporters had to drum up money and men from all Caernarfonshire to repair the breach and strengthen the whole embankment. By 1814 it was open again, but Madocks's finances were in ruins.[39] By 1836 the Ffestiniog Railway had opened its line across the embankment. It then become the main route for Ffestiniog slate to reach the new port at Porthmadog.[54] In 1927 the Cob was breached again and took several months to repair.[6] In 2012, 260 metres of the embankment were widened on the seaward side of the Porthmadog end to allow a second platform to be added to the Ffestiniog Railway's Harbour Station.

The former tollhouse at the north-western end of the Cob has slate-clad walls. It is one of few buildings to retain the interlocking slate ridge-tiles devised by Moses Kellow, manager of Croesor Quarry.[54] The toll was abolished in 2003 when the Welsh Assembly Government bought the Cob.[55]

Pen Cei, to the west of the harbour was a centre of the harbour's commercial activities. Boats were built and repaired. There were slate wharves for each quarry company with tracks connecting to the railway. Bron Guallt, built in 1895, was the Oakeley Quarry shipping agent's house.[56] Grisiau Mawr ("Big Steps") connected the quay to Garth and houses were built for the ship owners and sea captains.[26] A School of Navigation was also built.[7]

Melin Yr Wyddfa ("Snowdon Mill") on Heol Y Wyddfa is a former flour mill built in 1862. A scheme of renovation and conversion to luxury flats began there, but has yet to reach completion.[26]

The Welsh Highland Heritage Railway, not to be confused with Welsh Highland Railway, is a three-quarter-mile (1.2 km) heritage railway. It includes an award-winning miniature railway, a heritage centre, a shop and a cafe.

Kerfoots, in a Victorian building on Stryd Fawr, is a small department store founded in 1874. It contains a unique spiral staircase, chandeliers and slender cast-iron columns to support the upper floors. The Millennium Dome, constructed by local craftsmen in 1999 to mark the store's 125th anniversary, is made of stained glass depicting scenes from Porthmadog in 1874.[6]

The Royal Sportsman Hotel (Welsh: Gwesty'r Heliwr) on Stryd Fawr was built in 1862 as a staging post on the turnpike road to Porthdinllaen. The arrival of the railway five years later brought rising numbers of tourists, and the hotel soon became famous for its liveried carriage and horses to take guests to local sightseeing spots. The building is of Ffestiniog slate; the original stone and slate fireplaces remain.[57]

The War Memorial stands on top of Ynys Galch, one of the former islands reclaimed from Traeth Mawr.[58] Taking the form of a Celtic cross and standing 16 feet (4.9 m) high, it was fashioned from Trefor granite and unveiled "in memory of ninety-seven fallen war heroes of Madoc Vale" in 1922.[59]

On Moel y Gest, a hill above the town, is an Iron Age stone-walled hill fort.[60]

Education

Primary education takes place in three local schools. The bilingual Ysgol Eifion Wyn on Stryd Fawr, named after a local poet, Eliseus Williams (Eifion Wyn), has 204 pupils.[61] It moved into a new building in 2003. There are units for children with special educational needs and for those with language difficulties. At the last school inspection by Estyn in 2004 nine per cent of pupils were entitled to free school meals and 72 per cent came from homes where Welsh was the main spoken language.[62]

Ysgol Borth-y-Gest on Stryd Mersey, Borth-y-Gest, is the smallest of the schools with 70 pupils.[61] In 2009 Cyngor Gwynedd adopted a report, Excellent Primary Education For Children In Gwynedd, setting out the future for primary schools in the county.[63] The future of the school, built in 1880, had been in doubt.[64][65] In 2006, at the last inspection by Estyn, three per cent of pupils were entitled to free school meals and 20 per cent came from homes where Welsh was the main spoken language.[66]

Ysgol y Gorlan in Tremadog has 122 pupils.[61] When Estyn last inspected in 2008, ten per cent of pupils were entitled to free school meals and some 50 per cent came from homes where Welsh was the main spoken language.[67]

Ysgol Eifionydd in Stryd Fawr is a bilingual comprehensive school for ages 11 to 16, established about 1900. It has 484 pupils.[61] At the last Estyn inspection, in 2006, eight per cent of pupils were entitled to free school meals and Welsh was the main spoken language in the home for about 50 per cent. One per cent of pupils were from ethnic minority backgrounds.[68]

Transport

Porthmadog lies on the A487 trunk road between the Fishguard and Bangor. The A498 runs north from Porthmadog to Beddgelert, giving access to Snowdonia. The A497 runs west through the southern Llŷn Peninsula to Criccieth and Pwllheli. In 2008 the Welsh Assembly Government published plans for a A487 Porthmadog, Minffordd and Tremadog Bypass to reduce the amount of through traffic.[69] This officially opened on 17 October 2011.[70]

Of the town's three railway stations, Porthmadog on the Cambrian Coast Line between Pwllheli and Machynlleth is served by Transport for Wales for Shrewsbury, Wolverhampton and Birmingham.[71] Porthmadog Harbour at the southern end of Stryd Fawr, has been the Ffestiniog Railway terminus since passenger services started in 1865.[72] Since 2011 it is also the southern terminus of the rebuilt Welsh Highland Railway from Caernarfon.[73][74] The Welsh Highland Heritage Railway has its main station and visitor centre near the north end of Stryd Fawr on the former Cambrian Railways sidings opposite the mainline station. Trains run to Pen-y-Mount.[75]

Buses are run by Arriva Buses Wales, Gwynfor Coaches, Lloyds Coaches and Caelloi Motors, to Aberystwyth, Bangor, Beddgelert, Blaenau Ffestiniog, Caernarfon, Criccieth, Dolgellau, Machynlleth, Morfa Bychan, Penrhyndeudraeth, Pen-y-Pass, Portmeirion, Pwllheli, Rhyd and Tremadog.[76]

Notable people

- The local artist Rob Piercy, was named Welsh Artist of the Year in 2002.[77] Porthmadog-born painter Elfyn Lewis won the National Eisteddfod of Wales Gold Medal for fine art in 2009 and the Welsh Artist of the Year prize in 2010.[78]

- Three members of hip-hop band Genod Droog were from Porthmadog.[79] *Welsh singer Duffy shot her first video Rockferry in the town. Supergrass have filmed a video at Morfa Bychan and Portmeirion for the song "Alright", which featured in the 1995 album I Should Coco. Part of the movie Macbeth (1971) was filmed at Black Rock Sands, as well as the cover art photography for the Manic Street Preachers 1998 album This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours.[80]

- Morfa Bychan, is renowned as the home of David Owen, an 18th-century blind harpist and composer. He died at the age of 29 in 1741,[81] and tradition has it that as he lay on his death bed he called for his harp and composed the air Dafydd y Garreg Wen. Words were added nearly 100 years later by the poet John Ceiriog Hughes.[82]

- The Welsh-language poet William Ambrose (bardic name Emrys, 1813–1873) was minister of the Independent chapel in the town until his death.

- The ashes of the poet R. S. Thomas (1913–2000) are buried in the churchyard of St John's Church on Ffordd Penamser. An earlier poet who was brought up in the town was Mary Davies (1846–1882), who wrote in Welsh.[83]

- Thomas Edward Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia, was born at what is now Lawrence House in Tremadog in 1888. He became an object of fascination, renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt of 1916 and for his vivid writings about his experiences.[84]

- In order to finance the construction and repairs to the Cob, William Madocks let out his own house in Tremadog. His first tenant was the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who antagonised locals by criticising their production of sheep for consumption, and by running up debts with local merchants. Shelley made a hasty departure after an alleged attempt on his life by a nocturnal intruder, without paying his rent or contributing to the fund established to support Madocks.[39] During his tenancy, Shelley had written Queen Mab.[40]

- The Spooner family contributed a major amount towards the development of railways in the area over a period of more than 70 years in the 19th century.

- WWE Wrestler Mason Ryan real name Barri Griffiths is from the area.

Sport

Porthmadog Football Club, founded in 1884, is one of the oldest in Wales. Matches are played at Y Traeth. The club won the North Wales League in 1902/1903 and reached the final of the Welsh Amateur Cup in 1905/1906. It again won the league championship in 1937/1938, and was Welsh Amateur Cup winner in 1955/1956 and 1956/1957. It was league champion for three successive seasons between 1966 and 1969, and twice so in the 1970s. In 1989/1990 it topped the Welsh Alliance League and gained a place in the new Cymru Alliance. The club became an inaugural member of the League of Wales in 1992, in the first season finishing ninth. The following year Porthmadog striker Dave Taylor was the highest scoring player in Europe. The club nearly folded in 1995/1996 for financial reasons and lost its place in the League of Wales in 1998. It played the following year in the Cymru Alliance, winning the League Cup, but not until 2002/2003 did it gain a 19-point lead over its nearest rivals to win promotion again to the Welsh Premier League.[85] The club was heavily fined and had points deducted by the Football Association of Wales in 2007 after a referee was racially abused by a supporter, but an appeal to an independent tribunal reduced the fine and the points were reinstated.[86] In the 2008/2009 season Porthmadog narrowly avoided relegation, finishing 16th.[87]

Clwb Rygbi Porthmadog, based at Clwb Chwaraeon Madog, plays rugby union, competing in WRU Division 3 North organised by the Welsh Rugby Union. Having gained promotion from the Gwynedd league in the 2011/2012 season.[88]

Porthmadog Golf Club at Morfa Bychan opened in 1906 on land rented from a farmer. The original tenancy agreement stipulated that golfers must not take any game, hares, rabbits or wildfowl and must pay compensation for any sheep or cattle killed or injured by them. The landlord agreed not to turn on to the land any bull or savage cattle.[89] Created by James Braid, five times winner of the British Open, the course is a mixture of heath and links. The first nine holes head inland over heathland. The final nine, heading back towards the sea, are pure links. The 14th hole, known as The Himalayas, is a 378 yards (346 m) par 4 with a huge natural bunker hiding the green from the tee.[90]

Porthmadog Sailing Club, formed in 1958, initially operating from a marquee in a field. In 1964 the club amalgamated with Trawsfynydd Sailing Club and a clubhouse was built. Weekend dinghy racing is organised and facilities are provided for cruisers.[91]

Madoc Yacht Club, founded in 1970, is based in the former harbourmaster's office and has an extensive cruising and racing programme, including two races to Ireland. In 2001 a Celtic longboat was purchased and a sea-rowing section formed, which now has four boats. The club competes as part of the Welsh Sea Rowing Association [92]

Glaslyn Leisure Centre on Stryd y Llan has a 25-metre swimming pool and sports hall, badminton, squash and tennis courts, a sauna, a five-a-side football pitch and a dance studio.[93]

Sea angling is popular in the coast villages. Borth-y-Gest offers flounder, bass, mullet, whiting and mackerel.[94] Morfa Bychan provides bass, flounder, eel, whiting and occasional turbot.[95] Bass, flounder and huge schools of whiting are found at Black Rock Sands, along with thornback ray, mackerel and garfish.[96] Bass, flatfish, eel and some very large mullet can be caught in Porthmadog Harbour, in the heart of the town, though care must be taken to avoid taking the poisonous lesser weever.[97]

Glaslyn Angling Association controls fishing rights on most of the Afon Glaslyn up to Beddgelert. It mainly produces sea trout, but salmon and brown trout appear.[98] Although the river had suffered from acid rain and forestation, water quality has improved.[99][100] Glan Morfa Mawr Trout Fishery at Morfa Bychan is well stocked with rainbow trout[101]

A cycle route crosses the Cob as part of Lôn Las Cymru, the Welsh national cycle route from Holyhead in the north to either Cardiff or Chepstow in the south. It is 250 miles (400 km) long and crosses three mountain ranges.[102]

Tremadog's quality rock climbing attracts climbers from all over the United Kingdom, the dolerite cliffs often being dry when it is too wet to climb in the mountains of Snowdonia.[103] Craig Bwlch y Moch is seen as one of the best crags in Wales.[104]

A fell race, on the slopes of Moel y Gest known as "Râs Moel y Gest" is held each year, starting in the town.[105][106]

Bathing is popular at the extensive beach of Black Rock Sands. The water-quality prediction is "excellent".[107][108] Borth-y-Gest has a sand-and-pebble beach where bathing is safe inshore, but there are fast currents further out.[109]

References

- "British Broadcasting Corporation: What's in a Name: Porthmadog". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- City Population. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Whispernet (14 February 2008). "Gateway to Snowdonia". Porthmadog. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru: Eisteddfod Locations". Eisteddfod.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Ordnance Survey: Election Maps: Gwynedd". Election-maps.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- John Dobson and Roy Woods, Ffestiniog Railway Traveller's Guide, Festiniog Railway Company, Porthmadog, 2004.

- "Gwynedd Archaeological Trust: Porthmadog: Historic Background". Heneb.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Whispernet (14 February 2008). "Gateway to Snowdonia: Heritage". Porthmadog. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Porter, Darwin; Prince, Danforth (18 December 2006). Frommer's England 2007 – Google Books. ISBN 9780470084083. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- "Archif Melville Richards".

- "No. 22092". The London Gazette. 4 February 1858. pp. 550–551.

- "No. 27394". The London Gazette. 6 January 1902. pp. 127–128.

- A Vision of Britain Through Time: Porthmadog Urban District

- "Office of Public Sector Information: Local Government Act 1972: Revised: Schedule 4". Uk-legislation.hmso.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Council Elections: Porthmadog East". Gwynedd.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Council Elections: Porthmadog West". Gwynedd.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "National Assembly for Wales: 'The County of Gwynedd (Electoral Changes) Order 2002" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Council Elections: Porthmadog-Tremadog". Gwynedd.gov.uk. 15 August 2008. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Community Council Election: 1 May 2008". Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Statement of Persons Nominated: 1 May 2008". Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Member Profile". Welsh Parliament. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Boundary Commission for Wales: Final Recommendations for the National Assembly for Wales Electoral Regions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- The Roadside Geology of Wales: The Llŷn Peninsula

- "Snowdonia: Borth-y-Gest". Snowdoniaguide.com. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- The Weather Channel: Porthmadog Weather Archived 19 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Whispernet (14 February 2008). "Gateway to Snowdonia: Places to Visit". Porthmadog. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Borth-y-Gest". North Wales. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Parc y Borth Local Nature Reserve". Gwynedd.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Pen y Banc Local Nature Reserve". Gwynedd.gov.uk. 25 October 2007. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Beach Guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Morfa Bychan". Wales Directory. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "UK Windsurfers Online Community: Black Rock Sands". Iwindsurf.co.uk. 19 November 2003. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Mynediad Traeth Morfa Bychan Beach Entry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "North Wales Wildlife Trust: Morfa Bychan and Greenacres". Wildlifetrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 September 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- The Megalithic Portal and Megalith Map. "The Megalithic Portal: Cist Cerrig". Megalithic.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Peter Fenn, George Nash and Laurie Waite: Cist Cerrig: A Reassessment of a Ritual Landscape: Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club: Volume 8: pp. 135–137: 2007". Scribd.com. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "British Broadcasting Corporation: Remember 1996 (in Welsh)". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "—News Wales: 25 Year Legal Case Ends as Welsh Council Pay £1.9 million". Newswales.co.uk. 15 June 2001. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Cyfeillion Cadw Tremadog: A Brief History of Tremadog". Tremadog.org.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Gwynedd Archaeological Trust: Tan-yr-Allt". Heneb.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Neighbourhood Statistics. "Census 2001: Parish Profile: People: Porthmadog". Neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Snowdonia National Park Authority: Community Area Data: Porthmadog

- "A Vision of Britain Through Time: Total Population: Ynyscynhaiarn Civil Parish". Visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "A Vision of Britain Through Time: Total Population: Ynyscynhaiarn Urban District". Visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "A Vision of Britain Through Time: Total Population: Porthmadog Urban District". Visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- A Vision of Britain Through Time: Gazetteer Entries: Ynyscynhaiarn Civil Parish Archived 4 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "University of Essex: Online Historical Population Reports". Histpop.org. 1 July 2004. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Archives Wales: Caernarfon Record Office: Porthmadog Harbour Records". Archivesnetworkwales.info. 15 September 2004. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Peter Johnson, An Illustrated History of the Festiniog Railway, Oxford Publishing Co, 2006.

- "Gwynedd Ships: Porthmadog: The Port and the Ships". Freespace.virgin.net. 31 December 1945. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "The Industrial Railway Record: The Britannia Foundry". Irsociety.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "About Us". Y Ganolfan. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Gwefan Tremadog: Porthmadog Maritime Museum". Tremadog.org.uk. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Gwynedd Archaeological Trust: The Vale of Ffestiniog". Heneb.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Welsh Government |Assembly abolishes toll on Porthmadog Cob

- "Gwynedd Archaeological Trust: Porthmadog Harbour". Heneb.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Royal Sportsman Hotel". Royalsportsman.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "War Memorial". Geograph. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Welsh Stone Forum: Newsletter: Number 5: February 2008

- "Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales: Moel-y-Gest Hillfort". Coflein.gov.uk. 20 October 2003. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Cyngor Gwynedd: List of Schools

- Estyn: Inspection under Section 10 of the Schools Inspections Act 1996: Ysgol Eifion Wyn Archived 7 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Excellent Primary Education For Children In Gwynedd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "They've Just Spent £30k – Now They Want It Shut: 24 November 2007". Daily Post. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Tim Rheoli Corfforaethol" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- Estyn: Inspection under Section 10 of the Schools Inspections Act 1996: Ysgol Borth-y-Gest Archived 7 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Estyn: Inspection under Section 28 of the Education Act 2005: Ysgol y Gorlan

- Estyn: Inspection under Section 28 of the Schools Inspection Act 1996: Ysgol Eifionydd Archived 7 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Welsh Assembly Government: A487 Porthmadog, Minffordd and Tremadog Bypass". Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "BBC News – Bypass opens". Bbc.co.uk. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Arriva Trains Wales: Cambrian Lines Archived 28 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Ffestiniog Railway Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Project Rheilffordd Eryri: Dates for the Diary Archived 16 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Welsh Highland Railway

- "Welsh Highland Heritage Railway". Whr.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Cyngor Gwynedd: Bus Services Archived 25 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Rob Piercy Gallery Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Laura Chamberlain (21 June 2010) "Elfyn Lewis wins Welsh Artist of the Year prize", BBC Wales blog. Retrieved 2013-08-24.

- British Broadcasting Corporation: Genod Droog Archived 1 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Internet Movie Database: Movie Locations

- "Welsh Biography Online: David Owen". Wbo.llgc.org.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Project Gutenberg :John Ceiriog Hughes". Gutenberg.org. 31 December 2001. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Dictionary of Welsh Biography, National Library of Wales

- "T. E. Lawrence". Snowdon Lodge. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Emyr Gareth/Iwan Gareth/Gareth Williams. "Porthmadog Football Club: History". Porthmadogfc.com. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Emyr Gareth/Iwan Gareth/Gareth Williams. "Porthmadog Football Club: News". Porthmadogfc.com. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Emyr Gareth/Iwan Gareth/Gareth Williams. "Porthmadog Football Club: The Table". Porthmadogfc.com. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Clwb Rygbi Porthmadog: Croeso

- "History". Porthmadog Golf Club. 29 March 2013. Archived from the original on 14 August 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Porthmadog Golf Club". Porthmadog Golf Club. 29 March 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Porthmadog Sailing Club: Club History". Sailing-club.org. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Madoc Yacht Club: About Us Archived 25 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Cyngor Gwynedd: Glaslyn Leisure Centre". Gwynedd.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- World Sea Fishing: Borth-y-Gest Archived 10 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- World Sea Fishing: Morfa Bychan Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- World Sea Fishing: Black Rock Sands Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Angling Wales: Porthmadog Estuary". Sgeorges.clara.net. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Cyngor Gwynedd: Glaslyn Angling Association Archived 22 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Fishing Wales: River Glaslyn". Fishing.visitwales.com. 2 January 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Glaslyn Angling Association". Dwyforangling.info. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "Angling Wales". Angling Wales. Archived from the original on 21 October 2001. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Visit Wales: Lôn Las Cymru". Cycling.visitwales.com. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Craig Pant Ifan". UK Climbing. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Craig Bwlch y Moch". UK Climbing. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Bro Dysynni Athletics Club: News Report: 28 May 2007". Brodysynniac.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Welsh Fell Runners Association: Tuesday Night Series". Wfra.org.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Environment Agency: Water Quality Classification Predictions for Bathing Waters in England and Wales under the Revised Bathing Water Directive Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Environment Agency: Bathing Water Quality: Craig Du: 2008". Maps.environment-agency.gov.uk. 8 November 2012. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Criccieth: What to See: Borth-y-Gest". Ccbsweb.force9.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Porthmadog. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Porthmadog. |