Prizren

Prizren (Albanian: Prizren, definite form: Prizreni, Serbian Cyrillic: Призрен) is a city in Kosovo[lower-alpha 1] and the seat of the eponymous municipality and district. As of the constitution of Kosovo, the city is designated as the historical capital.[2]

Prizren

| |

|---|---|

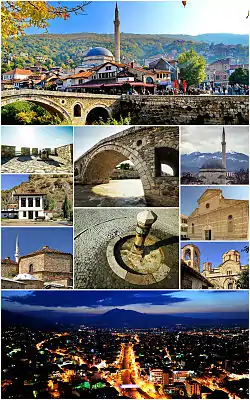

From top and left to right: The old town of Prizren, the fortress, Stone Bridge, Sinan Pasha Mosque, League of Prizren building, Shadervan Square, Cathedral of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour, Gazi Mehmet Pasha Hammam, Our Lady of Ljeviš and the city by night. | |

Flag  Seal | |

Prizren  Prizren | |

| Coordinates: 42°13′N 20°44′E | |

| Country | |

| District | Prizren |

| Municipality | Prizren |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mytaher Haskuka (Vetëvendosje) |

| Area | |

| • City | 22.39 km2 (8.64 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 640 km2 (250 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 450 m (1,480 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Municipality | 186,986 |

| • Urban | 85,119 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 20000-20080[1] |

| Area code(s) | +383 (0)29 |

| Vehicle registration | 04 |

| Website | kk.rks-gov.net/prizren |

According to the 2011 census, the city of Prizren has 85,119 inhabitants, while the municipality has 177,781 inhabitants.[3] Prizren is located on the banks of the Bistrica river and on the slopes of the Šar Mountains (Albanian: Malet e Sharrit) in southern Kosovo. The municipality has a border with Albania and North Macedonia.[4]

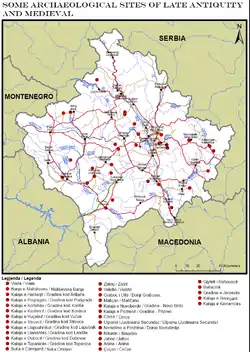

Prizren is one of the oldest settlements in Kosovo and the western Balkans. Archaeological excavations in Prizren Fortress indicate that its fortress area has seen habitation and use since the Bronze Age (ca. 2000 BCE). Prizren has been traditionally identified with the settlement of Theranda in Roman Dardania, although other locations have been suggested in recent research. In late antiquity it was part of the defensive fortification system in western Dardania and the fort was reconstructed in the era of eastern Roman Emperor Justinian. Byzantine rule in the region ended definitively in 1219-20 as the Serbian Nemanjić dynasty controlled the fort and the town until 1371. Since 1371, a series of regional feudal rulers came to control Prizren: the Balšić, the Dukagjini, the Hrebeljanović and finally the Branković, often with Ottoman support. The Ottoman Empire assumed direct control after 1450. Prizren first developed in the area below the fortress which overlooks the Bistrica river on its left bank. Since the 16th century, economic development fueled the expansion of the city's neighbourhoods to the river's right bank.

History

Early period

Prizren has been traditionally identified with Theranda, a town of the Roman era.[5] Another location which may have been that of Theranda is present-day Suhareka as has been suggested in recent research. Archaeological research has shown that the site of the Prizren Fortress has had several eras of habitation since prehistoric times. In its lower part, material from the upper part of the fort has been deposited over the centuries. It dates from the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000 BCE) to the late Iron Age (c. 1st century CE) and is comparable to the material found in the nearby prehistoric site in the village of Vlashnjë (~10km west of Prizren).[6] In 2005, prehistoric rock paintings in a ritual site related to the cycle of life were found near Vlashnjë. They represent the first find of prehistoric rock art in the region.[7]

In late antiquity, the fortification saw a phase of reconstruction. It is part of a series of forts that were built or reconstructed in the same period by Justinian along the White Drin in northern Albania and western Kosovo in the routes that linked the coastal areas with the Kosovo valley.[8] At this time, the Prizren fortress likely appears in historical record as Petrizen in the 6th century CE in the work of Procopius as one of the fortifications which Justinian commissioned to be reconstructed in Dardania.[6]

Present-day Prizren is first mentioned in 1019 at the time of Basil II (r. 976–1025) in the form of Prisdriana. In 1072, the leaders of the Bulgarian Uprising of Georgi Voiteh traveled from their center in Skopje in the area of Prizren and held a meeting in which they invited Mihailo Vojislavljević of Duklja to send them assistance. Mihailo sent his son, Constantine Bodin with 300 of his soldiers. Dalassenos Doukas, dux of Bulgaria was sent against the combined forced but was defeated near Prizren, which was extensively plundered by the Serbian army after the battle.[9] The Bulgarian magnates proclaimed Bodin "Emperor of the Bulgarians" after this initial victory.[10] They were defeated by Nikephoros Bryennios in the area of northern Macedonia by the end of 1072. The area was raided by Serbian ruler Vukan in the 1090s.[11] Demetrios Chomatenos is the last Byzantine archbishop of Ohrid to include Prizren in his jurisdiction until 1219.[12] Stefan Nemanja had seized the surrounding area along the White Drin between the 1180s and 1190s, but this may refer to the areas Prizren diocese rather than the fort and the settlement itself and he may have lost control of them later.[13][14] The ecclesiastical split of Prizren from the Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1219 was the final act of establishing Serbian Nemanjić rule in the town. Konstantin Jireček concluded, from the correspondence of archbishop Demetrios of Ohrid (1216–36), that Prizren was the northeasternmost area of Albanian settlement prior to the Slavic expansion.[15] Prizren and its fort were the administrative and economic center of the župa of Podrimlje (in Albanian, Podrima or Anadrini).[16] The old town of Prizren developed below the fortress along the left bank of the Bistrica/Lumbardhi. Ragusan traders were stationed in the old town. Prizren over time became a trading hub and gateway for Ragusan trade towards eastern Kosovo and beyond.[17]

With the death of Stefan Uroš V in 1371, a series of competing regional nobles sieged, counter-sieged and held control of Prizren - increasingly with Ottoman support and intervention. The first who tried to gain control of Prizren and the trade that passed through the town was Prince Marko, but after his defeat in the Battle of Maritsa, the Balšići of Zeta quickly moved to take Prizren soon after the battle in the fall and winter of 1371.[18] In the spring of 1372, Nikola Altomanović besieged Prizren and tried to expand his rule, but was defeated. The death George Balšić in 1377 created another power vacuum - Đurađ Branković took over Prizren for the first time at that time.[19]

The Catholic church retained some influence in the area; 14th-century documents refer to a catholic church in Prizren, which was the seat of a bishopric between the 1330s and 1380s. Catholic parishes served Ragusan merchants and Saxon miners.[20]

Ottoman Period

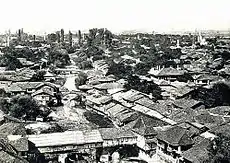

After several years of attack and counterattack, the Ottomans made a major invasion of Kosovo in 1454; Đurađ Branković retreated to the north and asked for help from John Hunyadi. On 21 June 1455, Prizren surrendered to the Ottoman army.[21] Prizren was the capital of the Sanjak of Prizren, and under new administrative organization of Ottoman Empire it became capital of the Vilayet.[22] This included the city of Tetovo.[23] Later it became a part of the Ottoman province of Rumelia. It was a prosperous trade city, benefiting from its position on the north-south and east-west trade routes across the Empire. Prizren became one of the larger cities of the Ottomans' Kosovo Province (vilayet). Prizren was the cultural and intellectual centre of Ottoman Kosovo. It was dominated by its Muslim population, who composed over 70% of its population in 1857. The city became a major Albanian cultural centre and the coordination political and cultural capital of the Kosovar Albanians. In 1871, a long Serbian seminary was opened in Prizren, discussing the possible joining of the old Serbia's territories with the Principality of Serbia.

It was an important part of Kosovo Vilayet between 1877 and 1912.

During the late 19th century the city became a focal point for Albanian nationalism and saw the creation in 1878 of the League of Prizren, a movement formed to seek the national unification and liberation of Albanians within the Ottoman Empire. The Young Turk Revolution was a step in the dissolving of the Ottoman empire that led to the Balkan Wars. The Third Army (Ottoman Empire) had a division in Prizren, the 30th Reserve Infantry Division (Otuzuncu Pirzerin Redif Fırkası).

Modern

.jpg.webp)

The Prizren attachment was part of the İpek Detachment in the Order of Battle, 19 October 1912 in the First Balkan War. During the First Balkan War the city was seized by the Serbian army and incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbia. Although the troops met little resistance, the takeover was bloody with 400 people dead in the first few days; the local population would call the city 'The Kingdom of Death'.[24] The Daily Chronicle reported on 12 November 1912 that 5,000 Albanians had been slaughtered in Prizren.[24] General Božidar Janković forced the local Albanian leaders to sign a declaration of gratitude to King Peter of Serbia for their 'liberation by the Serbian army.'[24][25] Following the capture of Prizren, most foreigners were barred from entering the city, for the Montenegrin forces temporarily closed the city before full control was restored. A few visitors did make it through—including Leon Trotsky, then working as a journalist for a Ukrainian newspaper and reports eventually emerged of widespread killings of Albanians.[26] In a 1912 news report on the Serbian Army and the Paramilitary Chetniks in Prizren, Trotsky stated "Among them were intellectuals, men of ideas, nationalist zealots, but these were isolated individuals. The rest were just thugs, robbers who had joined the army for the sake of loot... The Serbs in Old Serbia, in their national endeavour to correct data in the ethnographical statistics that are not quite favourable to them, are engaged quite simply in systematic extermination of the Muslim population".[27] British traveller Edith Durham and a British military attaché were supposed to visit Prizren in October 1912, however the trip was prevented by the authorities. Durham stated " I asked wounded Montengrins [Soldiers] why I was not allowed to go and they laughed and said 'We have not left a nose on an Albanian up there!' Not a pretty sight for a British officer." Eventually Durham visited a northern Albanian outpost in Kosovo where she met captured Ottoman soldiers whose upper lips and noses had been cut off.[27]

After the First Balkan War of 1912, the Conference of Ambassadors in London allowed the creation of the state of Albania and handed Kosovo to the Kingdom of Serbia, even though the population of Kosovo remained mostly Albanian.[28]

In 1913, an official Austro-Hungarian report recorded that 30,000 people had fled to Prizren from Bosnia.[29] In January 1914 the Austro-Hungarian consul based in Prizren conducted a detailed report on living conditions in the city. The report stated that Kingdom of Serbia didn't keep its promise for equal treatment of Albanians and Muslims. Thirty of the thirty-two Mosques in Prizren had been tuned into hay barns, ammunition stores and military barracks. The people of the city were heavily taxed with Muslims and Catholic Christians having to pay more tax than Orthodox Christians. The local government was predominately made up of former Serb Chetniks. The report also noted that the Serbs were also dissatisfied with the living conditions in Prizren.[29]

World War I and World War II

With the outbreak of the First World War, the Kingdom of Serbia was invaded by Austro-Hungarian forces and later by Bulgarian forces. By 29 November 1915, Prizren fell to Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian forces.[30] In April 1916, Austria-Hungary allowed the Kingdom of Bulgaria to occupy the city with the understanding that a significant amount of the city's population were ethnic Bulgarians.[31] During this period there was a process of forced Bulgarisation with many Serbs being interned; Serbs suffered worse in Bulgarian occupied regions of Kosovo compared to Austrian occupied regions due to the Bulgarian defeat in the Second Balkan War and due to the long-standing rivalry between the Bulgarian Orthodox Church and the Serbian Orthodox Church.[32] According to Catholic Archbishop of Skopje, Lazër Mjeda who was taking refuge in Prizren at the time, roughly 1,000 people had died of hunger in 1917. In October 1918 following the fall of Macedonia to Allied Forces, the Serbian Army along with the French 11th colonial division and the Italian 35th Division pushed the Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian forces out of the city.[32] By the end of 1918, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was formed. The Kingdom was renamed in 1929 to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Prizren became a part of its Vardar Banovina.

In World War II Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy invaded the Kingdom of Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941 and by 9 April the Germans who had invaded Yugoslavia from the East with neighbouring Bulgaria as base were on the outskirts of Prizren and by 14 April Prizren had fallen to the Italians who had invaded Yugoslavia from the West in neighbouring Albania; there was however notable resistance in Prizren before Yugoslavia unconditionally surrendered on 19 April 1941.[33] Prizren along with most of Kosovo was annexed to the Italian puppet state of Albania. Soon after the Italian occupation, the Albanian Fascist Party established a blackshirt battalion in Prizren, but plans to establish two more battalions were dropped due to the lack of public support.[34]

In 1943 Bedri Pejani of the German Wehrmacht helped create the Second League of Prizren.[35]

Federal Yugoslavia

In 1944, German forces were driven out of Kosovo by a combined Russian-Bulgarian force, and then the Communist government of Yugoslavia took control.[37] In 1946, the town was formulated as a part of Kosovo and Metohija which the Constitution defined the Autonomous Region of Kosovo and Metohija within the People's Republic of Serbia, a constituent state of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia.

The Province was renamed to Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo in 1974, remaining part of the Socialist Republic of Serbia, but having attributions similar to a Socialist Republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The former status was restored in 1989, and officially in 1990.

For many years after the restoration of Serbian rule, Prizren and the region of Dečani to the west remained centres of Albanian nationalism. In 1956 the Yugoslav secret police put on trial in Prizren nine Kosovo Albanians accused of having been infiltrated into the country by the (hostile) Communist Albanian regime of Enver Hoxha. The "Prizren trial" became something of a cause célèbre after it emerged that a number of leading Yugoslav Communists had allegedly had contacts with the accused. The nine accused were all convicted and sentenced to long prison sentences, but were released and declared innocent in 1968 with Kosovo's assembly declaring that the trial had been "staged and mendacious."

Kosovo War

The town of Prizren did not suffer much during the Kosovo War but its surrounding municipality was badly affected 1998–1999. Before the war, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe estimated that the municipality's population was about 78% Kosovo Albanian, 5% Serb and 17% from other national communities. During the war most of the Albanian population were either forced or intimidated into leaving the town. Tusus Neighborhood suffered the most. Some twenty-seven to thirty-four people were killed and over one hundred houses were burned.[38]

At the end of the war in June 1999, most of the Albanian population returned to Prizren. Serbian and Roma minorities fled, with the OSCE estimating that 97% of Serbs and 60% of Romani had left Prizren by October. The community is now predominantly ethnically Albanian, but other minorities such as Turkish, Ashkali (a minority declaring itself as Albanian Roma) and Bosniak (including Torbesh community) live there as well, be that in the city itself, or in villages around. Such locations include Sredska, Mamushë, the region of Gora, etc.

The war and its aftermath caused only a moderate amount of damage to the city compared to other cities in Kosovo.[39] Serbian forces destroyed an important Albanian cultural monument in Prizren, the League of Prizren building,[40][41] but the complex was rebuilt later on and now constitutes the Albanian League of Prizren Museum.

On 17 March 2004, during the Unrest in Kosovo some Serb cultural monuments in Prizren were damaged, burned or destroyed, including Orthodox Serb churches, such as Our Lady of Ljeviš from 1307 (UNESCO World Heritage Site),[42] the Church of Holy Salvation,[42] Church of St. George[42] (the city's largest church), Church of St. George[42] (Runjevac), Church of St. Kyriaki, Church of St. Nicolas (Tutić Church),[42] the Monastery of The Holy Archangels,[42] as well as Prizren's Orthodox seminary of Saint Cyrillus and Methodius.[42]

Also, during that riot, entire Serb quarter of Prizren, near the Prizren Fortress, was completely destroyed, and all remaining Serb population was evicted from Prizren.[43][44] Simultaneously Islamic cultural heritage and Mosques were being destroyed and damaged in Prizren.

21st century

The municipality of Prizren is still the most culturally and ethnically heterogeneous of Kosovo, retaining communities of Bosniaks, Turks, and Romani in addition to the majority Kosovo Albanian population live in Prizren. Only a small number of Kosovo Serbs remains in Prizren and area, residing in small villages, enclaves, or protected housing complexes. Furthermore, Prizren's Turkish community is socially prominent and influential, and the Turkish language is widely spoken even by non-ethnic Turks.

Geography

Prizren is located on the slopes of the Šar Mountains (Albanian: Malet e Sharrit) in southern Kosovo.[lower-alpha 1] on both banks of the Bistrica river. The municipality has a border crossings with Albania and North Macedonia. The municipality of Prizren covers an area of 640 km2 (5.94% of Kosovo’s surface). It has 76 settlements in total. The municipality borders the municipalities of Suhareka/Suva Reka and Rahovec/ Orahovac to the north, the municipality of Dragash to the south, Štrpce and the border with North Macedonia to the east and to the west borders with Albania.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Prizren features a humid subtropical climate. The city generally features very cool winters, with an average high of 3.3 °C (37.9 °F) in January, and sultry summers, with an average high of 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) in July. Precipitation is generally evenly spread throughout the course of the year, with the city seeing on average 850 mm of precipitation annually.

| Climate data for Prizren (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.2 (68.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

33.8 (92.8) |

40.6 (105.1) |

40.8 (105.4) |

37.3 (99.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.4 (88.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

40.8 (105.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

1.8 (35.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.6 (−10.5) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−23.6 (−10.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 76.2 (3.00) |

54.1 (2.13) |

63.5 (2.50) |

61.1 (2.41) |

66.7 (2.63) |

69.7 (2.74) |

58.6 (2.31) |

127.4 (5.02) |

58.2 (2.29) |

55.1 (2.17) |

88.3 (3.48) |

81.1 (3.19) |

860.0 (33.86) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12.8 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 12.6 | 13.5 | 133.6 |

| Average snowy days | 7.6 | 5.6 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.1 | 5.8 | 25.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 75 | 68 | 64 | 64 | 61 | 58 | 59 | 67 | 74 | 79 | 82 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 100.2 | 92.0 | 139.4 | 176.2 | 224.5 | 290.7 | 300.8 | 285.7 | 220.7 | 163.4 | 89.7 | 54.1 | 2,137.4 |

| Source: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[45] | |||||||||||||

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 63,587 | — |

| 1953 | 68,583 | +1.52% |

| 1961 | 79,594 | +1.88% |

| 1971 | 111,067 | +3.39% |

| 1981 | 152,562 | +3.23% |

| 1991 | 200,584 | +2.77% |

| 2011 | 177,781 | −0.60% |

| 2016 est. | 186,986 | +1.01% |

| Source: Division of Kosovo | ||

The presence of Vlach villages in the vicinity of Prizren is attested in 1198-1199 by a charter of Stephan Nemanja.[46] The nearby placename Vlashnja refers to the historical Vlach population. According to Serbian scholars, although Albanians lived between Lake Skadar and the Devoll river in the 1100s, Albanian migration into the plains of Metohija (Albanian: Dukagjin) commenced at the end of the century.[47]

Madgearu argues that the series of Ottoman defters from 1455 onward showing the "ethnic mosaic" of Serb and Albanian villages in Kosovo shows that Prizren already had significant Albanian Muslim populations.[48] Since an early period in its rapid development as an Ottoman city, Prizren had much more Muslims than Catholic or Orthodox inhabitants as in the pre-Ottoman period. This is highlighted in primary accounts of the 16th and early 17th century. Catholic bishop Pjetër Mazreku noted in 1624 that the Catholics of Prizren were 200, the Serbs (Orthodox) 600, and Muslims, almost all of whom were Albanians, numbered 12,000.[49]

Due to urban development in the Ottoman period, with the building of mosques and other Islamic buildings, Prizren received an Islamic urban character in the 16th century. 227 of 246 workshops of Prizren were run by Muslims in 1571.[50] Catholic archbishop Marino Bizzi reported in 1610 that Prizren had 8,600 houses, out of which many were Orthodox (who had two churches), and only 30 were Catholic (who had one church).[51] The Orthodox far outnumbered the Catholics.[52] Catholic archbishop Pjetër Mazreku reported in 1624 that the town was inhabited by 12,000 "Turks" (Muslims) of which most spoke Albanian, and that there were 600 Serbs (Orthodox Christians) and maybe 200 Catholic Albanians.[53] In 1857, Russian Slavist Alexander Hilferding's publications place the Muslim families at 3,000, the Orthodox ones at 900 and the Catholics at around 100 families.[54] In the Ottoman census of 1876, it had 43,922 inhabitants.[54]

According to the 2011 census results, the municipal area of Prizren had a population of 177,781 inhabitants. Albanian, Serbian, Bosnian, and Turkish are official languages.[55][56]

The ethnic composition of the municipal area of the city of Prizren:

| Ethnic group | Population 1991 |

Population 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Albanians | 132,591 | 145,718 |

| Bosniaks | 19,423 | 16,896 |

| Turks | 7,227 | 9,091 |

| Romani | 3,963 | 2,889 |

| Serbs | 10,950 | 237 |

| Others | 1,259 | 2,940 |

| Total | 175,413 | 177,781 |

Education

There are 48 primary schools with 28,205 pupils and 1,599 teachers; 6 secondary schools with 9,608 students and 503 teachers; kindergartens are privately run. There is also a public university in Prizren, offering lectures in Albanian, Bosnian, and Turkish. (source: municipal directorate of education and science).

Health

The primary health care system includes 14 municipal family health centres and 26 health houses. The primary health sector has 475 employees, including doctors, nurses and support staff, 264 female and 211 male. Regional hospital in Prizren offers services to approximately 250,000 residents. The hospital employs 778 workers, including 155 doctors, and is equipped with emergency and intensive care units.

Economy

For a long time the economy of Kosovo was based on the retail industry fueled by remittance income coming from a large number of immigrant communities in Western Europe. Private enterprise, mostly small business, is slowly emerging. Private businesses, like elsewhere in Kosovo, predominantly face difficulties because of a lack of structural capacity to grow. Education is poor, financial institutions basic, and regulatory institutions lack experience. Securing capital investment from foreign entities cannot emerge in such an environment. Due to financial hardships, several companies and factories have closed and others are reducing personnel. This general economic downturn contributes directly to the growing rate of unemployment and poverty, making the economic viability in the region more tenuous.[57]

Many restaurants, private retail stores, and service-related businesses operate out of small shops. Larger grocery and department stores have recently opened. In town, there are eight sizeable markets, including three produce markets, one car market, one cattle market, and three personal hygiene and houseware markets. There is an abundance of kiosks selling small goods. However, reducing international presence and repatriation of refugees and internally displaced persons is expected to further strain the local economy. Market saturation, high unemployment, and a reduction of financial remittances from abroad are negative economic indicators.[57]

There are three agricultural co-operatives in three villages. Most livestock breeding and agricultural production are private, informal, and small-scale. There are nine operational banks with branches in Prizren, ProCredit Bank, the Raiffeisen Bank, the NLB Bank, TEB Bank, Banka për Biznes (Bank for Business), İşbank, Banka Kombëtare Tregtare (National Trade Bank), Iutecredit, and the Payment and Banking Authority of Kosovo (BPK).[57]

Infrastructure

All the main roads connecting the major villages with the urban centre are asphalted. The water supply is functional in Prizren town and in approximately 30 villages. There is no sewage system in the villages. Power supply is still a problem, especially during the winter and in the villages.

Culture

Prizren is home to the annually held documentary film festival Dokufest.

The city is also home to numerous mosques, Orthodox and Catholic churches and other monuments. Among them:

- Sinan Pasha Mosque

- The Mosque of Muderis Ali Efendi

- Mosque Katip Sinan Qelebi

- Our Lady of Ljeviš church

- The St. George Cathedral

- Church of Holy Salvation

- Saint Archangels Monastery

- League of Prizren Monument

- Kaljaja fortress

- Church of St. Nicholas

- Church of St. Kyriaki

- Cathedral of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour

- The Lorenc Antoni Music school

- Theater

- Shuaip Pasha's House

- Orthodox Seminary of Prizren

Sports

The city has one sports club known as KF Liria based in Prizren near Kosovo. They currently play in the Football Superleague of Kosovo. The city is also home to one of the best basketball teams in Kosovo, K.B Bashkimi. They are currently playing in the top professional men's basketball league in Kosovo, Kosovo Basketball Superleague

Events and festivals

NGOM Fest is a music festival established in Prizren. The word "Ngom" means "Listen to me" in the Gheg Albanian dialect. The first edition of the festival was held on June 2011 and due to its success, further events were organised. The main objectives of the festival are to promote new bands and artists, build a new perspective for music festivals in Kosovo, and to connect different ethnic groups in Kosovo and in the region.[58][59] 40BunarFest is an annual non traditional festival of alternative sport held in Prizren.

See also

Notes

- Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008. Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 98 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 113 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition.

References

- "The Postal Code of Kosovo has been approved by the Universal Postal Union (UPU) and by UNMIK Legal Office" (PDF). PTK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Ligji Nr. 06/L-012 për Kryeqytetin e Republikës së Kosovës, Prishtinën" (in Albanian). Gazeta Zyrtare e Republikës së Kosovës. 6 June 2018. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "Preliminary Results of the Kosovo 2011 population and housing census". The statistical Office of Kosovo. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: A Modern History. I.B.Tauris. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9.

- Galaty 2013, p. 68.

- Hoxha 2007, p. 270

- Shukriu 2006, p. 59

- Hoxha 2007, p. 271.

- Stojkovski 2020, p. 147.

- McGeer 2019, p. 149.

- Fine 1994, p. 226.

- Prinzing 2008, p. 30.

- Novaković 1966, pp. 191-215.

- Fine 1994, p. 7.

- Ducellier, Alain (1999-10-21). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, c.1198-c.1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 780. ISBN 978-0-521-36289-4. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

The question of Illyrian continuity was already addressed by Jireček, 1916 p 69–70, and in the same collection, p 127–8, admitting that the territory occupied by the Albanians extended, prior to Slav expansion, from Scutari to Valona and from Prizren to Ohrid, utilizing in particular the correspondence of Demetrios Chomatenos; Circovic (1988) p347; cf Mirdita (1981)

- Rrezja 2011, p. 254.

- Rrezja 2011, p. 267.

- Fine 1994, p. 383.

- Fine 1994, p. 389.

- Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-8147-5561-7.

- Malcolm, N (1999). Kosovo: A Short History. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-06-097775-7.

- http://www.komuna-prizreni.org/repository/docs/PRIZREN-CITY_MUSEUM.pdf

- "muja-live". Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- Freundlich, Leo (1913). "Albania's Golgotha". Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Lazër Mjeda (24 January 1913). "Report on the Serb Invasion of Kosova and Macedonia". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "Prizren history". Archived from the original on 2012-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- Noel Malcolm (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: papermac. p. 253. ISBN 9780330412247.

- "Prizren history". Archived from the original on 2011-11-18.

- Noel Malcolm (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: papermac. p. 258. ISBN 9780330412247.

- Noel Malcolm (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: papermac. p. 260. ISBN 9780330412247.

- Noel Malcolm (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: papermac. p. 261. ISBN 9780330412247.

- Noel Malcolm (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: papermac. p. 262. ISBN 9780330412247.

- Noel Malcolm (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: papermac. p. 290. ISBN 9780330412247.

- Noel Malcolm (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: papermac. p. 295. ISBN 9780330412247.

- "Die aktuelle deutsche Unterstützung für die UCK". Trend.infopartisan.net. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- Elsie, Robert. "The Photo Collection of Josef Székely". www.albanianphotography.net.

- Malcolm, Noel (2002). Kosovo: A short history. p. 311. ISBN 0-330-41224-8.

- Human Rights Watch, 2001 Under orders: war crimes in Kosovo, page 339. ISBN 1-56432-264-5

- Human Rights Watch, 2001 Under orders: war crimes in Kosovo, page 338. ISBN 1-56432-264-5

- Andras Riedlmayer, Harvard University Kosovo Cultural Heritage Survey Archived 2012-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- The Human Rights Centre, Law Faculty, University of Pristina, 2009 Ending Mass Atrocities: Echoes in Southern Cultures Archived 2011-08-13 at the Wayback Machine, page 3

- "Reconstruction Implementation Commission". Site on protection list. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- Failure to Protect: Anti-Monority Violence in Kosovo , March 2004. Wuman Right Watch. 2004. p. 9.

- Warrander, Gail (2008). Kosovo. Bradt. p. 191. ISBN 9781841621999.

- "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1961–1990" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Madgearu. The Wars of the Balkan Peninsula. Page 33.

- Madgearu, Alexander and Gordon, Martin. The Wars of the Balkan Peninsula: Their Medieval Origins. Page 25

- Madgearu, Alexander and Gordon, Martin. The Wars of the Balkan Peninsula: Their Medieval Origins. Page 27

- Malcolm 2020, p. 136.

- Egro, Dritan (2010). Oliver Jens Schmitt (ed.). Islam in the Albanian lands (XVth-XVIIth century). Religion und Kultur Im Albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa. Peter Lang. pp. 34, 36, 39–40, 48. ISBN 978-3-631-60295-9. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb (1995). "Prizren". The Encyclopaedia of Islam: NED-SAM. Brill. p. 339.

- Arshi Pipa; Sami Repishti (1984). Studies on Kosova. East European Monographs. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-88033-047-3.

- Kristaq Prifti (1993). The Truth on Kosova. Encyclopaedia Publishing House. p. 39.

- Elsie 2004, p. 144.

- Diplomatic Observer Archived 2008-05-26 at the Wayback Machine Official Language

- OSCE Implementation of the Law on the Use of Languages by Kosovo Municipalities

- "Bosnia and Herzegovina Republika Srpska National Assembly Elections". Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 22–23 November 1997. p. 32. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- "Southeast Europe: People and Culture: NGOM Festival". www.southeast-europe.eu. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-07-10. Retrieved 2014-03-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography

- Fine, John V. A. (John Van Antwerp) (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- Galaty, Michael; Lafe, Ols; Lee, Wayne; Tafilica, Zamir (2013). Light and Shadow: Isolation and Interaction in the Shala Valley of Northern Albania. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. ISBN 978-1931745710.

- Machiel, Kiel (1990). Ottoman Architecture in Albania, 1385-1912. Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. ISBN 9290633301.

- Malcolm, Noel (2020). Rebels, Believers, Survivors: Studies in the History of the Albanians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192599223.

- McGeer, Eric (2019). Byzantium in the Time of Troubles: The Continuation of the Chronicle of John Skylitzes (1057-1079). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004419407.

- Hoxha, Gëzim (2007). "Të dhëna të reja arkeologjike nga Kalaja e Prizrenit / Nouvelles données archéologiques sur la forteresse de Prizren". Iliria. 33: 33. doi:10.3406/iliri.2007.1073.

- Novaković, R (1966). "O nekim pitanjima područja današnje Metohije krajem XII i početkom XIII veka". Zbornik Radova Vizantološkog Instituta. 9: 195–215.

- Prinzing, Günter (2008). "Demetrios Chomatenos, Zu seinem Leben und Wirken". Demetrii Chomateni Ponemata diaphora: [Das Aktencorpus des Ohrider Erzbischofs Demetrios. Einleitung, kritischer Text und Indices]. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110204506.

- Rrezja, Agon (2011). "Zhupa e Podrimës sipas burimeve cirilike të shek. XII-XV / District of Podrima according to Cyrillic sources of the 12th-15th centuries". Gjurmime Albanologjike. Albanological Institute of Pristina. 41–42.

- Stojkovski, Boris (2020). "Byzantine military campaigns against Serbian lands and Hungary in the second half of the eleventh century.". In Theotokis, Georgios; Meško, Marek (eds.). War in Eleventh-Century Byzantium. Routledge. ISBN 978-0429574771.

- Shukriu, Edi (2006). "Spirals of the prehistoric open rock painting from Kosova". Proceedings of the XV World Congress of the International Union for Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences. 35.

External links

- Municipality of Prizren – Official Website