Kosovo Albanians

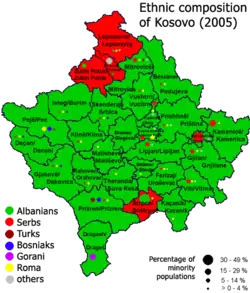

The Albanians of Kosovo (Albanian: Shqiptarët e Kosovës, pronounced [ʃcipˈta:ɾət ɛ kos'ov:əs]), also commonly called Kosovo Albanians, Kosovar Albanians or simply Kosovars, constitute the largest ethnic group in Kosovo.[a]

Albanians in Kosovo (2011 census) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–3 million | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other regions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Albanian (Gheg Albanian) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Islam (majority) Christianity (minority) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Albanians | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

Native Albania · Kosovo Croatia · Greece · Italy · Montenegro · North Macedonia · Serbia Diaspora Australia · Bulgaria · Denmark · Egypt · Finland · Germany · Norway · Romania · South America · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom · United States |

| Culture |

| Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Dance · Dress · Literature · Music · Mythology · Politics · Religion · Symbols · Traditions · Fis |

| Religion |

| Christianity (Catholicism · Orthodoxy · Protestantism) · Islam (Sunnism · Bektashism) · Judaism |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Albanian Gheg (Arbanasi · Upper Reka · Istrian) · Tosk (Arbëresh · Arvanitika · Calabria Arbëresh · Cham · Lab) |

| History of Albania |

According to the 1991 Yugoslav census, boycotted by Albanians, there were 1,596,072 ethnic Albanians in Kosovo or 81.6% of population. By the estimation in year 2000, there were between 1,584,000 and 1,733,600 Albanians in Kosovo or 88% of population; as of 2011,[1] their population share is 92.93%. Albanians of Kosovo are Ghegs.[10] They speak Gheg Albanian, more specifically the Northwestern and Northeastern Gheg variants.

History

Middle Ages

Kosovo Albanians belong to the ethnic Albanian sub-group of Ghegs, who inhabit the north of Albania, north of the Shkumbin river, Kosovo, southern Serbia, and western parts of North Macedonia.

In the 14th century in two chrysobulls or decrees by Serbian rulers, villages of Albanians alongside Vlachs are cited in the first as being between the White Drin and Lim rivers (1330), and in the second (1348) a total of nine Albanian villages are cited within the vicinity of Prizren.[11][12] Toponyms such as Arbanaška and Đjake shows an Albanian presence in the Toplica and Southern Morava regions (located north-east of contemporary Kosovo) since the Late Middle Ages.[13][14] Significant clusters of Albanian populations also lived in Kosovo especially in the west and centre before and after the Habsburg invasion of 1689–1690, while in Eastern Kosovo they were a small minority.[15][16] Due to the Ottoman-Habsburg wars and their aftermath, Albanians from contemporary northern Albania and Western Kosovo settled in wider Kosovo and the Toplica and Morava regions in the second half of the 18th century, at times instigated by Ottoman authorities.[17][14]

According to Noel Malcolm, a large part of the Albanian demographic growth in Kosovo was from an indigenous population within the Kosovo region itself rather than a mass immigration from northern Albania. [18] Most of the new arrivals into Kosovo that were recorded by Ottoman officials in the early period had Slavic names rather than Albanian, many of these coming from Bosnia[19] By the 1600's, large parts of Western Kosovo were majority Albanian speaking and migrations from northern Albania into Kosovo at this period were relatively very small compared to the already existing Albanian population in Kosovo.[20] The population of northern and central Albania in the early Ottoman period was also smaller than that of the population of Kosovo and it's rate of growth higher. [21]

In the Middle Ages, more Albanians in Kosovo were concentrated in the western parts of the region than in its eastern part. In the late 17th century,[22] most intensively between mid-18th century and the 1840s they seem to have moved eastwards. The migrating parts of tribes maintained a tribal outlook and household structure. A 1930s Serbian study by Atanasije Urošević estimated that 90% of Kosovo Albanians in particular areas of eastern Kosovo descended from these migrating tribes; most belonged to the Krasniqi, the rest to the Berisha, Gashi, Shala, Sopi, Kryeziu, Thaçi and Bytyqi tribes.[23][24] Historian Noel Malcolm has criticized the Urošević study for its broad generalization to the whole of Kosovo, as it focused on Eastern Kosovo, while omitting Western Kosovo to reach those conclusions.[24] Malcolm also noted that commonalities of Kosovo Albanian family names with Albanian clan names is not always indicative of having Albanian Malësi clan origins, as some people were agglomerated into clans while many other Kosovo Albanians lack such names.[22] The study also revealed that the same population figures between older and newer settlement patterns were the same for the Serb population in eastern Kosovo as most had settled in the area in the last 200 years.[22]

Kosovo was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1455 to 1912, at first as part of the eyalet of Rumelia, and from 1864 as a separate province (vilayet). During this time, Islam was introduced to the population. Today, Sunni Islam is the predominant religion of Kosovo Albanians.

The Ottoman term Arnavudluk (آرناوودلق) meaning Albania was used in Ottoman state records for areas such as southern Serbia and Kosovo.[15][25][26] Evliya Çelebi (1611–1682) in his travels within the region during 1660 referred to the western and central part of what is today Kosovo as Arnavudluk and described the town of Vučitrn's inhabitants as having knowledge of Albanian or Turkish with few speakers of Slavic languages.[15]

19th century

A large number of Albanians alongside smaller numbers of urban Turks (with some being of Albanian origin) were expelled and/or fled from what is now contemporary southern Serbia (Toplica and Morava regions) during the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78).[27] Many settled in Kosovo, where they and their descendants are known as muhaxhir, also muhaxher ("exiles", from Arabic 'muhajir'),[27] and some bear the surname Muhaxhiri/Muhaxheri or most others the village name of origin.[28] During the late Ottoman period, ethno-national Albanian identity as expressed in contemporary times did not exist amongst the wider Kosovo Albanian-speaking population.[29] Instead collective identities were based upon either socio-professional, socio-economic, regional, or religious identities and sometimes relations between Muslim and Christian Albanians were tense.[29]

As a reaction against the Congress of Berlin, which had given some Albanian-populated territories to Serbia and Montenegro, Albanians, mostly from Kosovo, formed the League of Prizren in Prizren in June 1878. Hundreds of Albanian leaders gathered in Prizren and opposed the Serbian and Montenegrin jurisdiction. Serbia complained to the Western Powers that the promised territories were not being held because the Ottomans were hesitating to do that. Western Powers put pressure to the Ottomans and in 1881, the Ottoman Army started the fighting against Albanians. The Prizren League created a Provisional Government with a President, Prime Minister (Ymer Prizreni) and Ministries of War (Sylejman Vokshi) and Foreign Ministry (Abdyl Frashëri). After three years of war, the Albanians were defeated. Many of the leaders were executed and imprisoned. In 1910, an Albanian uprising spread from Pristina and lasted until the Ottoman Sultan's visit to Kosovo in June 1911. The aim of the League of Prizren was to unite the four Albanian-inhabited Vilayets by merging the majority of Albanian inhabitants within the Ottoman Empire into one Albanian vilayet. However at that time Serbs consisted about 25%[30] of the whole Vilayet of Kosovo's overall population and were opposing the Albanian aims along with Turks and other Slavs in Kosovo, which prevented the Albanian movements from establishing their rule over Kosovo.

20th century

In 1912 during the Balkan Wars, most of eastern Kosovo was taken by the Kingdom of Serbia, while the Kingdom of Montenegro took western Kosovo, which a majority of its inhabitants call "the plateau of Dukagjin" (Rrafshi i Dukagjinit) and the Serbs call Metohija (Метохија), a Greek word meant for the landed dependencies of a monastery. Aside from many war crimes and atrocities committed by the Serbian Army on the Albanian population, colonist Serb families moved into Kosovo, while the Albanian population was decreased. As a result, the proportion of Albanians in Kosovo declined from 75 percent[30][31] at the time of the invasion to slightly more than 65%[31] percent by 1941.

The 1918–1929 period under the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was a time of persecution of the Kosovar Albanians. Kosovo was split into four counties—three being a part of official Serbia: Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija; and one in Montenegro: northern Metohija. However, the new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three Regions in the Kingdom: Kosovo, Rascia and Zeta.

In 1929 the Kingdom was transformed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The territories of Kosovo were split among the Banate of Zeta, the Banate of Morava and the Banate of Vardar. The Kingdom lasted until the World War II Axis invasion of April 1941.

After the Axis invasion, the greater part of Kosovo became a part of Italian-controlled Fascist Albania, and a smaller, Eastern part by the Axis allied Tsardom of Bulgaria and Nazi German-occupied Serbia. Since the Albanian Fascist political leadership had decided in the Conference of Bujan that Kosovo would remain a part of Albania they started expelling the Serbian and Montenegrin settlers "who had arrived in the 1920s and 1930s".[33] Prior to the surrender of Fascist Italy in 1943, the German forces took over direct control of the region. After numerous Serbian and Yugoslav Partisans uprisings, Kosovo was liberated after 1944 with the help of the Albanian partisans of the Comintern, and became a province of Serbia within the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

The Autonomous Region of Kosovo and Metohija was formed in 1946 to placate its regional Albanian population within the People's Republic of Serbia as a member of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia under the leadership of the former Partisan leader, Josip Broz Tito, but with no factual autonomy. This was the first time Kosovo came to exist with its present boundaries. After Yugoslavia's name changed to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia's to the Socialist Republic of Serbia in 1963, the Autonomous Region of Kosovo was raised to the level of Autonomus Province (which Vojvodina had had since 1946) and gained inner autonomy in the 1960s.

In the 1974 constitution, the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo's government received higher powers, including the highest governmental titles—President and Premier and a seat in the Federal Presidency, which made it a de facto Socialist Republic within the Federation, but remaining as a Socialist Autonomous Region within the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Serbo-Croat and Albanian were defined official on the provincial level marking the two largest linguistic Kosovan groups: Serbs and Albanians. The word Metohija was also removed from the title in 1974 leaving the simple short form, Kosovo.

In the 1970s, an Albanian nationalist movement pursued full recognition of the Province of Kosovo as another Republic within the Federation, while the most extreme elements aimed for full-scale independence. Tito's government dealt with the situation swiftly, but only giving it a temporary solution.

In 1981 the Kosovar Albanian students organised protests seeking that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia. Those protests were harshly contained by the centralist Yugoslav government. In 1986, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) was working on a document, which later would be known as the SANU Memorandum. An unfinished edition was filtered to the press. In the essay, SANU portrayed the Serbian people as a victim and called for the revival of Serb nationalism, using both true and exaggerated facts for propaganda. During this time, Slobodan Milošević rose to power in the League of the Socialists of Serbia.

Soon afterwards, as approved by the Assembly in 1990, the autonomy of Kosovo was revoked, and the pre-1974 status reinstated. Milošević, however, did not remove Kosovo's seat from the Federal Presidency, but he installed his own supporters in that seat, so he could gain power in the Federal government. After Slovenia's secession from Yugoslavia in 1991, Milošević used the seat to obtain dominance over the Federal government, outvoting his opponents.

Many Albanians organized a peaceful active resistance movement, following the job losses suffered by some of them, while other, more radical and nationalistic oriented Albanians, started violent purges of the non-Albanian residents of Kosovo.

On 2 July 1990, an unconstitutional ethnic Albanian parliament declared Kosovo an independent country, although this was not recognized by the Government since the ethnic Albanians refused to register themselves as legal citizens of Yugoslavia. In September of that year, the ethnic Albanian parliament, meeting in secrecy in the town of Kačanik, adopted the Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo. A year later, the Parliament organized the 1991 Kosovan independence referendum, which was observed by international organisations, but was not recognized internationally because of a lot of irregularities. With an 87% turnout, 99.88% voted for Kosovo to be independent.[34] The non-Albanian population, at the time comprising 10% of Kosovo's population, refused to vote since they considered the referendum to be illegal.[35] In the early nineties, ethnic Albanians organised a parallel state system and a parallel system of education and healthcare, among other things, Albanians organized and trained, with the help of some European countries, the army of the self-declared Kosovo republic called the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). With the events in Bosnia and Croatia coming to an end, the Yugoslav government started relocating Serbian refugees from Croatia and Bosnia to Kosovo. The OVK managed to re-relocate Serbian refugees back to Serbia..

After the Dayton Agreement in 1995, a guerilla force calling itself the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) started to operate in Kosovo, although there are speculations that they may have started as early as 1992. Serbian paramilitary forces committed war crimes in Kosovo, although the Serbian government claims that the Army was only going after suspected Albanian terrorists. This triggered a 78-day NATO bombing campaign in 1999. The Albanian Kosovar KLA played a major role not only in reconnaissance missions for the NATO, but in sabotaging the Serbian Army as well.

21st century

International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244, which ended the Kosovo conflict of 1999. While Serbia's continued sovereignty over Kosovo is recognised by much of the international community, a clear majority of Kosovo's population prefers independence. The UN-backed talks, led by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. While progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[36] In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution that proposes 'supervised independence' for the province. As of early July 2007 the draft resolution, which is backed by the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the United Nations Security Council, had been rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty.[37] Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, has stated that it will not support any resolution that is not acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina.[38]

On 26 November 2019, an earthquake struck Albania. The Kosovo Albanian population reacted with sentiments of solidarity through fundraising initiatives and money, food, clothing and shelter donations.[39] Volunteers and humanitarian aid in trucks, buses and hundreds of cars from Kosovo traveled to Albania to assist in the situation and people were involved in tasks such as the operation of mobile kitchens and gathering fincncial aid.[39][40][41] Many Albanians in Kosovo have opened their homes to people displaced by the earthquake.[42][40][41]

Demographics

| Year | Albanians | Serbs | Others | Source and notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 61% | 33% | 6% | |

| 1931 | 58% | 29% | 13% | |

| 1948 | 65% | 26% | 9% | ICTY[43] |

| 1953 | 65% | 24% | 10% | |

| 1961 | 67% | 23% | 9% | |

| 1971 | 73% | 19% | 7% | |

| 1981 | 76% | 16% | 8% | |

| 1991 | 80% | 13% | 7% | 1991 Census[44] |

| 2000 | 87% | 9% | 4% | World Bank, OSCE[45] |

| 2007 | 92% | 5% | 3% | OSCE[45] |

| 2011 | 92.9% | 1.5% | 5.4% | 2011 Census[46] |

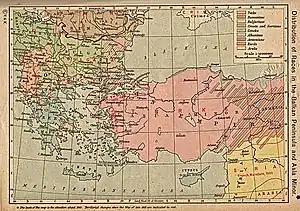

.jpg.webp) 1877 ethnic composition map of the Balkans by the pro-Greek French A. Synvet[47]

1877 ethnic composition map of the Balkans by the pro-Greek French A. Synvet[47] 1880 ethnographic map of the Balkans

1880 ethnographic map of the Balkans 1898 ethnic composition of the Balkans according to a French source

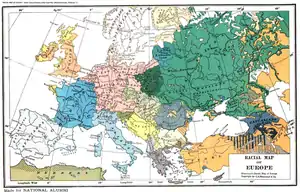

1898 ethnic composition of the Balkans according to a French source 1922 ethnographic map of Europe

1922 ethnographic map of Europe 1923 ethnographic map of the Balkans and Turkey.

1923 ethnographic map of the Balkans and Turkey.

Diaspora

There is a large Kosovo Albanian diaspora in central Europe.

Culture

Culturally, Albanians in Kosovo are very closely related to Albanians in Albania. Traditions and customs differ even from town to town in Kosovo itself. The spoken dialect is Gheg, typical of northern Albanians. The language of state institutions, education, books, media and newspapers is the standard dialect of Albanian, which is closer to the Tosk dialect.

Religion

The vast majority of Kosovo Albanians are Sunni Muslims. There are also Catholic Albanian communities concentrated in Gjakova, Prizren, Klina and a few villages near Peć and Vitina.

Art

Kosovafilmi is the film industry, which releases movies in Albanian, created by Kosovar Albanian movie-makers. The National Theatre of Kosovo is the main theatre where plays are shown regularly by Albanian and international artists.

Music

Music has always been part of Albanian culture. Although in Kosovo music is diverse (as it was mixed with the cultures of different regimes dominating Kosovo), authentic Albanian music does still exist. It is characterized by use of çiftelia (an authentic Albanian instrument), mandolina, mandola and percussion.

Folk music is very popular in Kosovo. There are many folk singers and ensembles.

Modern music in Kosovo has its origin from western countries. The main modern genres include pop, hip hop/rap, rock, and jazz.

Kosovo Radiotelevisions like RTK, RTV21 and KTV have their musical charts.

Education

Education is provided for all levels, primary, secondary, and university degrees. University of Pristina is the public university of Kosovo, with several faculties and majors. The National Library (BK) is the main and the largest library in Kosovo, located in the centre of Pristina. There are many other private universities, among them American University in Kosovo (AUK), and many secondary schools and colleges such as Mehmet Akif College.

Notable people

See also

- Albanians

- Albanian nationalism in Kosovo

- Albania-Kosovo relations

Notes

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008. Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 98 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 113 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition. |

References

- "Minority Communities in the 2011 Kosovo Census Results: Analysis and Recommendations" (PDF). European Centre for Minority Issues Kosovo. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Elsie,R.Historical Dictionary of Kosovo (2010) .pg.276

- "Emigration in Kosovo (International Emigation) – Page 32-38". Kosovo Agency of Statistics, KAS. Archived from the original on 15 June 2014.

- "Die kosovarische Bevölkerung in der Schweiz" (PDF).

- "Donner une autre image de la diaspora kosovare". Le Temps. 21 January 2009.

- "Kosovari in Italia".

- "Population by Ethnicity – Detailed Classification, 2011 Census". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

-

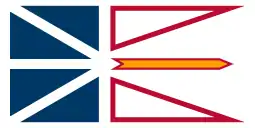

Newfoundland and Labrador 8,5 duizend Kosovaren in Nederland

Newfoundland and Labrador 8,5 duizend Kosovaren in Nederland - "Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. 25 October 2017.

- Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World music: the rough guide. Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

Most of the ethnic Albanians that live outside the country are Ghegs, although there is a small Tosk population clustered around the shores of lakes Presp and Ohrid in the south of Macedonia.

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. Macmillan. p. 54. ISBN 9780810874831. "From the details of the monastic estates given in the chrysobulls, further information can be gleaned about these Vlachs and Albanians. The earliest reference is in one of Nemanja's charters giving property to Hilandar, the Serbian monastery on Mount Athos: 170 Vlachs are mentioned, probably located in villages round Prizren. When Dečanski founded his monastery of Decani in 1330, he referred to ‘villages and katuns of Vlachs and Albanians’ in the area of the white Drin: a katun (alb.:katund) was a shepherding settlement. And Dusan’s chrysobull of 1348 for the Monastery of the Holy Archangels in Prizren mentions a total of nine Albanian katuns."

- Wilkinson, Henry Robert (1955). "Jugoslav Kosmet: The evolution of a frontier province and its landscape". Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers). 21 (21): 183. JSTOR 621279. "The monastery at Dečani stands on a terrace commanding passes into High Albania. When Stefan Uros III founded it in 1330, he gave it many villages in the plain and catuns of Vlachs and Albanians between the Lim and the Beli Drim. Vlachs and Albanians had to carry salt for the monastery and provide it with serf labour."

- Uka, Sabit (2004). Jeta dhe veprimtaria e sqiptarëve të Sanxhakut të Nishit deri më 1912 [Life and activity of Albanians in the Sanjak of Nish up to 1912]. Verana. pp. 244–245. "Eshtë, po ashtu, me peshë historike një shënim i M. Gj Miliçeviqit, i cili bën fjalë përkitazi me Ivan Begun. Ivan Begu, sipas tij ishte pjesëmarrës në Luftën e Kosovës 1389. Në mbështetje të vendbanimit të tij, Ivan Kullës, fshati emërtohet Ivan Kulla (Kulla e Ivanit), që gjendet në mes të Kurshumlisë dhe Prokuplës. M. Gj. Miliçeviqi thotë: "Shqiptarët e ruajten fshatin Ivan Kullë (1877–1878) dhe nuk lejuan që të shkatërrohet ajo". Ata, shqiptaret e Ivan Kullës (1877–1878) i thanë M. Gj. Miliçeviqit se janë aty që nga para Luftës se Kosovës (1389). [12] Dhe treguan që trupat e arrave, që ndodhen aty, ata i pat mbjellë Ivan beu. Atypari, në malin Gjakë, nodhet kështjella që i shërbeu Ivanit (Gjonit) dhe shqiptarëve për t’u mbrojtur. Aty ka pasur gjurma jo vetëm nga shekulli XIII dhe XIV, por edhe të shekullit XV ku vërehen gjurmat mjaft të shumta toponimike si fshati Arbanashka, lumi Arbanashka, mali Arbanashka, fshati Gjakë, mali Gjakë e tjerë. [13] Në shekullin XVI përmendet lagja shqiptare Pllanë jo larg Prokuplës. [14] Ne këtë shekull përmenden edhe shqiptarët katolike në qytetin Prokuplë, në Nish, në Prishtinë dhe në Bulgari.[15].... [12] M. Đj. Miličević. Kralevina Srbije, Novi Krajevi. Beograd, 1884: 354. "Kur flet mbi fshatin Ivankullë cekë se banorët shqiptarë ndodheshin aty prej Betejës së Kosovës 1389. Banorët e Ivankullës në krye me Ivan Begun jetojnë aty prej shek. XIV dhe janë me origjinë shqiptare. Shqiptarët u takojnë të tri konfesioneve, por shumica e tyre i takojnë atij musliman, mandej ortodoks dhe një pakicë i përket konfesionit katolik." [13] Oblast Brankovića, Opširni katastarski popis iz 1455 godine, përgatitur nga M. Handžic, H. Hadžibegić i E. Kovačević, Sarajevo, 1972: 216. [14] Skënder Rizaj, T,K "Perparimi" i vitit XIX, Prishtinë 1973: 57.[15] Jovan M. Tomić, O Arnautima u Srbiji, Beograd, 1913: 13.

- Geniş, Şerife; Maynard, Kelly Lynne (2009). "Formation of a Diasporic Community: The History of Migration and Resettlement of Muslim Albanians in the Black Sea Region of Turkey". Middle Eastern Studies. 45 (4): 553–569. doi:10.1080/00263200903009619. S2CID 143742189.

pp. 556–557: Using secondary sources, we establish that there have been Albanians living in the area of Nish for at least 500 years, that the Ottoman Empire controlled the area from the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries which led to many Albanians converting to Islam, that the Muslim Albanians of Nish were forced to leave in 1878, and that at that time most of these Nishan Albanians migrated south into Kosovo, although some went to Skopje in Macedonia. ; pp. 557–558: In 1690 much of the population of the city and surrounding area was killed or fled, and there was an emigration of Albanians from the Malësia e Madhe (North Central Albania/Eastern Montenegro) and Dukagjin Plateau (Western Kosovo) into Nish.

- Anscombe, Frederic F, (2006). "The Ottoman Empire in Recent International Politics – II: The Case of Kosovo". The International History Review. 28.(4): 767–774, 785–788. "While the ethnic roots of some settlements can be determined from the Ottoman records, Serbian and Albanian historians have at times read too much into them in their running dispute over the ethnic history of early Ottoman Kosovo. Their attempts to use early Ottoman provincial surveys (tahrir defterleri) to gauge the ethnic make—up of the population in the fifteenth century have proved little. Leaving aside questions arising from the dialects and pronunciation of the census scribes, interpreters, and even priests who baptized those recorded, no natural law binds ethnicity to name. Imitation, in which the customs, tastes, and even names of those in the public eye are copied by the less exalted, is a time—tested tradition and one followed in the Ottoman Empire. Some Christian sipahis in early Ottoman Albania took such Turkic names as Timurtaş, for example, in a kind of cultural conformity completed later by conversion to Islam. Such cultural mimicry makes onomastics an inappropriate tool for anyone wishing to use Ottoman records to prove claims so modern as to have been irrelevant to the pre-modern state. The seventeenth-century Ottoman notable arid author Evliya Çelebi, who wrote a massive account of his travels around the empire and abroad, included in it details of local society that normally would not appear in official correspondence; for this reason, his account of a visit to several towns in Kosovo in 1660 is extremely valuable. Evliya confirms that western and at least parts of central Kosovo were ‘Arnavud’. He notes that the town of Vučitrn had few speakers of ‘Boşnakca’; its inhabitants spoke Albanian or Turkish. He terms the highlands around Tetovo (in Macedonia), Peć, and Prizren the ‘mountains of Arnavudluk’. Elsewhere, he states that ‘the mountains of Peć’ lay in Arnavudluk, from which issued one of the rivers converging at Mitrovica, just north-west of which he sites Kosovo’s border with Bosna. This river, the Ibar, flows from a source in the mountains of Montenegro north-north-west of Peć, in the region of Rozaje to which the Këlmendi would later be moved. He names the other river running by Mitrovica as the Kılab and says that it, too, had its source in Aravudluk; by this, he apparently meant the Lab, which today is the name of the river descending from mountains north—east of Mitrovica to join the Sitnica north of Priština. As Evliya travelled south, he appears to have named the entire stretch of river he was following the Kılab, not noting the change of name when he took the right fork at the confluence of the Lab and Sitnica. Thus, Evliya states that the tomb of Murad I, killed in the battle of Kosovo Polje, stood beside the Kılab, although it stands near the Sitnica outside Priština. Despite the confusion of names, Evliya included in Arnavudluk not only the western fringe of Kosovo, but also the central mountains from which the Sitnica (‘Kılab’) and its first tributaries descend. Given that a large Albanian population lived in Kosovo, especially in the west and centre, both before and after the Habsburg invasion of 1689–90, it remains possible, in theory, that at that time in the Ottoman Empire, one people emigrated en masse and another immigrated to take its place.

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. Macmillan. p. 114. "What a straightforward reading of all this evidence would suggest is that there were significant reservoirs of a mainly Catholic Albanian-speaking population in parts of Western Kosovo, and evidence from the following century suggests that many of these eventually became Muslims. Whether Albanian-speakers were a majority in Western Kosovo at this time seems very doubtful, and it is clear that they were only a small minority in the east. On the other hand, it is also clear that the Albanian minority in Eastern Kosovo predated the Ottoman conquest."

- Jagodić, Miloš (1998). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878 Archived October 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Balkanologie. 2 (2): para. 10, 12.

- Kosovo: A Short History

- Kosovo: A Short History

- Kosovo: A Short History

- Kosovo: A Short History

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. Macmillan. p.155. "Thus increasingly, Albanians from the Malësi would bear the name of their clan as a kind of surname: Berisha, Këlmendi, Shala and so on. There are many people with these names in modern Kosovo, and it is clear that, from the early seventeenth century onwards, at least some of their ancestors must have come into Kosovo as immigrants from the Malësi. (‘At least some’ is a necessary qualification, because we cannot assume that the prices of agglomeration – of people joining a clan and taking its name – never took place on Kosovo soil.) However, there are also many Kosovo Albanians who do not bear clan names. Serbian writers sometimes argue that all these Albanians must therefore be Albanianized Serbs, as if all genuine Albanians would originally have belonged to clans. But since we know that there were non-clan Albanians in Kosovo as early as the fifteenth century, that there were only formed in areas which (unlike Kosovo) lacked governmental security, and indeed that many of the clans in the Malësi were still only in the process of formation at that time, this particular version of the argument about ‘Albanianized Serbs’ can simply be dismissed."

- Karl Kaser (2012). Household and Family in the Balkans: Two Decades of Historical Family Research at University of Graz. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 124–. ISBN 978-3-643-50406-7.

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. Macmillan. p. 179. "In the 1930s a Serb researcher took down details of the oral family traditions of all the households in several areas of Eastern Kosovo. He recorded that only a small proportion of Serb families had been living in the same place for 200 years or more. In one large section of Eastern Kosovo, running north and south of Prishtina, he was able to categorize the Serb households as follows: leaving aside the 1,437 colonist families who had come after 1912, there were 706 households of ‘old inhabitants’ and 1,819 households of ‘immigrants’. The family traditions of the latter recorded that 780 of them had come from Macedonia, northern Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia-Hercegovina and central or northern Serbia, while the rest had moved from other parts of Kosovo. In the Gornja Morava district (the south-east corner of Kosovo) the Serb population consisted of 1,143 households of old inhabitants and 1,205 of ‘immigrants’, fewer than 200 of whom had migrated from other parts of Kosovo. Of the Albanian families he investigated in these areas, only a small number were ‘old inhabitants’. The proportions would have been difficult if he had done his research in Western Kosovo; but in any case the whole debate which pits fixed Serbs against mobile Albanians, as his researches demonstrate, rather bogus. Most of the families in any part of Kosovo are known to have come from somewhere else."; p. 397. footnote: "Urošević, Etnički procesi na Kosovu tokom turske vladavine, pp. 18–20, 22–3."

- Anscombe, Frederick F. (2006). "The Ottoman Empire in Recent International Politics-II: The Case of Kosovo". The International History Review. 28 (4): 758–793. doi:10.1080/07075332.2006.9641103. JSTOR 40109813. S2CID 154724667.

In this case, however, Ottoman records contain useful information about the ethnicities of the leading actors in the story. In comparison with ‘Serbs’, who were not a meaningful category to the Ottoman state, its records refer to ‘Albanians’ more frequently than to many other cultural or linguistic groups. The term ‘Arnavud’ was used to denote persons who spoke one of the dialects of Albanian, came from the mountainous country in the western Balkans (referred to as ‘Arnavudluk’, and including not only the area now forming the state of Albania but also neighbouring parts of Greece, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Montenegro), organized society on the strength of blood ties (family, clan, tribe), engaged predominantly in a mix of settled agriculture and livestock herding, and were notable fighters – a group, in short, difficult to control. Other peoples, such as Georgians, Ahkhaz, Circassians, Tatars, Kurds, and Bedouin Arabs who were frequently identified by their ethnicity, shared similar cultural traits.

- Kolovos, Elias (2007). The Ottoman Empire, the Balkans, the Greek lands: toward a social and economic history: studies in honor of John C. Alexander Archived 20 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Isis Press. p. 41. "Anscombe (ibid., 107 n. 3) notes that Ottoman "Albania" or Arnavudluk... included parts of present-day northern Greece, western Macedonia, southern Montenegro, Kosovo, and southern Serbia"; see also El2. s.v. "Arnawutluk. 6. History" (H. İnalcık) and Arsh, He Alvania. 31.33, 39–40. For the Byzantine period. see Psimouli, Souli. 28."

- Jagodić, Miloš (1998). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. Revue d'Études Pluridisciplinaires. Balkanologie (Vol. II, n° 2).

- Uka, Sabit (2004). E drejta mbi vatrat dhe pasuritë reale dhe autoktone nuk vjetërohet: të dhëna në formë rezimeje [The rights of homes and assets, real and autochthonous that does not disappear with time: Data given in the form of estate portions regarding inheritance]. Shoqata e Muhaxhirëvë të Kosovës. pp. 52–54.

- Frantz, Eva Anne (2011). "Catholic Albanian warriors for the Sultan in late Ottoman Kosovo: The Fandi as a socio-professional group and their identity patterns Archived January 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine". In Grandits, Hannes, Nathalie Clayer, & Robert Pichler (eds). Conflicting Loyalties in the Balkans: The Great Powers, the Ottoman Empire and Nation-building. IB Tauris. p. 183. "It also demonstrates that while an ethno-national Albanian identity covering the whole Albanian-speaking population hardly existed in late-Ottoman Kosovo, collective identities were primarily formed from layers of religious, socio-professional/socio-economic and regional elements, as well as extended kinship and patriarchal structures.”; p. 195. “The case of the Fandi illustrates the heterogeneous and multilayered nature of the Albanian-speaking population groups in late-Ottoman Kosovo. These divisions also become evident when looking at the previously-mentioned high level of violence within the Albanian-speaking groups. Whereas we tend to think of violence in Kosovo today largely in terms of ethnic conflict or even “ancient ethnic hatreds”, the various forms of violence the consuls described in their reports in late-Ottoman Kosovo appear to have occurred primarily along religious and socio-economic fault lines, reflecting pre-national identity patterns. In addition to the usual violence prompted by shortages of pastureland or robbery for private gain, the sources often report on religiously motivated violence between Muslims and Christians, with a high level of violence not only between Albanian Muslims and Serbian Christians, but also between Albanian Muslims and Albanian Catholics.”

- Malcolm, Noel (26 February 2008). "Is Kosovo Serbia? We ask a historian". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Prishtine – mon amour". bturn.com. 7 September 2012.

- The Emerging Strategic Environment: Challenges of the Twenty-First Century – Google Boeken

- ch, Beat Müller, beat (at-sign) sudd (dot). "Kosovo (Jugoslawien), 30 September 1991 : Unabhängigkeit – [in German]". sudd.ch. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- Kosovo (Yugoslavia), 30 September 1991: Independence Direct Democracy (in German)

- "UN frustrated by Kosovo deadlock Archived March 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine", BBC News, 9 October 2006.

- Russia reportedly rejects fourth draft resolution on Kosovo status (SETimes.com) Archived 2 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- UN Security Council remains divided on Kosovo (SETimes.com) Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Krasniqi, Jeta (28 November 2019). "Kosovo's Heart Bleeds for Albania's Suffering". Balkaninsight. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Kostreci, Keida (30 November 2019). "Albania Search, Rescue Operation For Earthquake Survivors Ends". Voice of America (VOA). Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Kostreci, Keida (2 December 2019). "Albania Seeks International Support for Earthquake Recovery". Voice of America (VOA). Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Shqiptarët solidarizohen me tërmetin, ja sa është shuma e grumbulluar deri më tani" (in Albanian). Insajderi. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- "Report on the size and ethnic composition of the population of Kosovo" (PDF). ICTY. 14 August 2002.

- Bugajski, Janusz (2002). Political Parties of Eastern Europe: A Guide to Politics in the Post-Communist Era. New York: The Center for Strategic and International Studies. p. 479. ISBN 978-1563246760.

- Statistics Office of Kosovo, World Bank (2000), OSCE (2007)

- "ECMI: Minority figures in Kosovo census to be used with reservations". ECMI. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- Robert Shannan Peckham, Map mania: nationalism and the politics of place in Greece, 1870–1922, Political Geography, 2000, p. 4: "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Other maps by among others the Frenchman F. Bianconi [1877], who was the chief architect and engineer of the Ottoman railways, A. Synvet [1877] and Karl Sax [1878], a former Austrian consul in Adrianople, were similarly favourable to the Greek cause."