Subotica

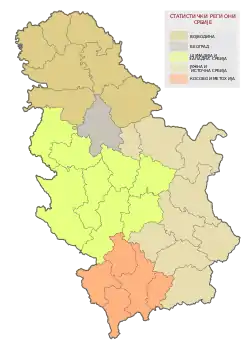

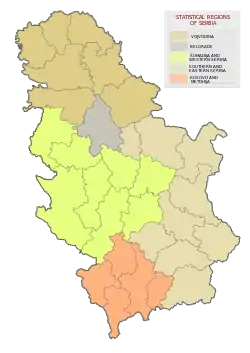

Subotica (Serbian Cyrillic: Суботица, [sǔbotitsa] (![]() listen); Hungarian: Szabadka) is a city and the administrative center of the North Bačka District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. Formerly the largest city of Vojvodina region, contemporary Subotica is now the second largest city in the province, following the city of Novi Sad. According to the 2011 census, the city itself has a population of 97,910, while the urban area of Subotica (with adjacent urban settlement of Palić included) has 105,681 inhabitants, and the population of metro area (the administrative area of the city) stands at 141,554 people.[1]

listen); Hungarian: Szabadka) is a city and the administrative center of the North Bačka District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. Formerly the largest city of Vojvodina region, contemporary Subotica is now the second largest city in the province, following the city of Novi Sad. According to the 2011 census, the city itself has a population of 97,910, while the urban area of Subotica (with adjacent urban settlement of Palić included) has 105,681 inhabitants, and the population of metro area (the administrative area of the city) stands at 141,554 people.[1]

Subotica

| |

|---|---|

| City of Subotica | |

.jpg.webp)   .jpg.webp) .jpg.webp)  From top: Panorama of Subotica, City center, City hall, Subotica Synagogue, Reichel Palace, St. Theresa of Avila Cathedral, Monument to the Victims of Fascism | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Subotica Location of the city of Subotica in Serbia | |

| Coordinates: 46°06′01″N 19°39′56″E | |

| Country | Serbia |

| Province | Vojvodina |

| District | North Bačka |

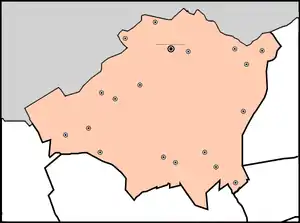

| Settlements | 19 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Stevan Bakić (SNS) |

| Area | |

| Area rank | 13th in Serbia |

| • Urban | 164.33 km2 (63.45 sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 1,007.47 km2 (388.99 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 109 m (358 ft) |

| Population (2011 census)[1] | |

| • City | 97,910 |

| • Rank | 6th in Serbia |

| • Urban | 105,681 |

| • Urban density | 640/km2 (1,700/sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 141,554 |

| • Administrative density | 140/km2 (360/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 24000 |

| Area code(s) | (+381) 24 |

| Vehicle registration | SU |

| Website | Official website |

Name

The earliest known written name of the city was Zabotka[2] or Zabatka,[3] which dates from 1391. It is the origin of the current Hungarian name for the city "Szabadka".[3][4]

According to one opinion, the Name "Szabadka" comes from the adjective szabad,[4] which derived from the Slavic word for "free" – svobod.[5][6][7] According to this view, Subotica's earliest designation would mean, therefore, something like a "free place".[4]

The origin of the earliest form of the name (Zabotka or Zabatka) is obscure.[8] However, according to a local Bunjevci newspaper, Zabatka could have derived from the South Slavic word "zabat" (Gable), which describe parts of Pannonian Slavic houses.[9]

The town was named in the 1740s after Maria Theresa of Austria, Archduchess of Austria. It was officially called Sent-Maria in 1743, but was renamed in 1779 as Maria-Theresiapolis. These two official names were also spelled in several different ways (most commonly the German Maria-Theresiopel or Theresiopel), and were used in different languages.

Geography

It is located in the Pannonian Basin at 46.07° North, 19.68° East, about 10 kilometres (6 miles) from the border with Hungary, and is the northernmost city in Serbia. It is located in the vicinity of lake Palić.

Climate

| Climate data for Subotica (Elevation: 109 m (358 ft)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

17.6 (63.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

16.0 (60.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

0.9 (33.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

5.6 (42.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 28 (1.10) |

25 (1.00) |

28 (1.10) |

41 (1.60) |

51 (2.00) |

71 (2.80) |

51 (2.00) |

56 (2.20) |

33 (1.30) |

25 (1.00) |

41 (1.60) |

41 (1.60) |

491 (19.3) |

| Source: Weather Channel[10] | |||||||||||||

History

Prehistory and antiquity

In Neolithic and Eneolithic period, several important archaeological cultures flourished in this area, including the Starčevo culture,[11] the Vinča culture,[12] and the Tiszapolgár culture.[13] The first Indo-European peoples settled in the territory of present-day Subotica in 4200 BC. During the Eneolithic period, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, several Indo-European archaeological cultures included areas around Subotica - the Baden culture, the Vučedol culture,[14] the Urnfield culture[15] and some other. Before the Iazyge conquest in the 1st century, Indo-European peoples of Illyrian, Celtic and Dacian descent inhabited this area. In the 3rd century BC, this area was controlled by Celtic Boii and Eravisci, while in the 1st century BC, it became part of the Dacian kingdom. Since the 1st century, the area came under the control of the Sarmatian Iazyges (which possibly included Serboi tribe), who occasionally were allies and occasionally enemies of the Romans. Iazyge rule lasted until the 4th century, after which the region came into the possession of various other peoples and states.

Early Middle Ages and Slavic settlement

In the Early Middle Ages various Indo-European and Turkic peoples and states ruled in the area of Subotica. These peoples included Huns, Gepids, Avars, Slavs and Bulgarians. Slavs settled today's Subotica in the 6th and 7th centuries, before some of them crossed the rivers Sava and Danube and settled in the Balkans.

The Slavic tribe living in the territory of present-day Subotica were the Obotrites, a subgroup of the Serbs. In the 9th century, after the fall of the Avar state, the first forms of Slavic statehood emerged in this area. The first Slavic states that ruled over this region included the Principality of Lower Pannonia, Great Moravia and the Bulgarian Empire.

Late-Middle Ages

Subotica probably first became a settlement of note when people poured into it from nearby villages destroyed during the Tatar invasions of 1241–42. However the settlement has surely been older. It has been established that people inhabited these territories even 3000 years ago. When Zabadka/Zabatka was first recorded in 1391, it was a tiny town in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Later, the city belonged to the Hunyadis, one of the most influential aristocratic families in the whole of Central Europe.

King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary gave the town to one of his relatives, János Pongrác Dengelegi, who, fearing an invasion by the Ottoman Empire, fortified the castle of Subotica, erecting a fortress in 1470. Some decades later, after the Battle of Mohács in 1526, Subotica became part of the Ottoman Empire. The majority of the Hungarian population fled northward to Royal Hungary. Bálint Török, a local noble who had ruled over Subotica, also escaped from the city. During the military and political havoc following the defeat at Mohács, Subotica came under the control of Serbian mercenaries recruited in Banat. These soldiers were in the service of the Transylvanian general John I Zápolya, a later Hungarian king.

The leader of these mercenaries, Jovan Nenad, established in 1526–27 his rule in Bačka, northern Banat and a small part of Syrmia and created an independent entity, with Subotica as its administrative centre. At the peak of his power, Jovan Nenad proclaimed himself as Serbian tsar in Subotica. He named Radoslav Čelnik as the general commander of his army, while his treasurer and palatine was Subota Vrlić, a Serbian noble from Jagodina. When Bálint Török returned and recaptured Subotica from the Serbs, Jovan Nenad moved the administrative centre to Szeged.[16]

Some months later, in the summer of 1527, Jovan Nenad was assassinated and his entity collapsed. However, after Jovan Nenad's death, Radoslav Čelnik led the remains of the army to Ottoman Syrmia, where he briefly ruled as an Ottoman vassal.

Ottoman administration

![]() Ottoman Empire 1542–1686

Ottoman Empire 1542–1686

![]() Habsburg Monarchy 1686–1804

Habsburg Monarchy 1686–1804

![]() Austrian Empire 1804–1867

Austrian Empire 1804–1867

![]() Austro-Hungarian Empire 1867–1918

Austro-Hungarian Empire 1867–1918

![]() Kingdom of Serbia 1918

Kingdom of Serbia 1918

![]() Kingdom of Yugoslavia[17] 1918–1941

Kingdom of Yugoslavia[17] 1918–1941

![]() Hungarian occupation of Yugoslavia 1941–1944

Hungarian occupation of Yugoslavia 1941–1944

![]() SFR Yugoslavia[18] 1944–1992

SFR Yugoslavia[18] 1944–1992

![]() Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 1992−2003

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 1992−2003

![]() Serbia and Montenegro 2003–2006

Serbia and Montenegro 2003–2006

The Ottoman Empire ruled the city from 1542 to 1686. At the end of this almost 150-year-long period, not much remained of the old town of Zabadka/Zabatka. As much of the population had fled, the Ottomans encouraged the settlement of the area by different colonists from the Balkans. The settlers were mostly Orthodox Serbs. They cultivated the extremely fertile land around Subotica. In 1570, the population of Subotica numbered 49 houses, and in 1590, 63 houses. In 1687, the region was settled by Catholic Dalmatas (called Bunjevci today). It was called Sobotka under Ottoman rule and was a kaza centre in Segedin sanjak at first in Budin Eyaleti until 1596, and after that in Eğri Eyaleti between 1596–1686.[19]

Habsburg administration

In 1687, about 5,000 Bunjevci, led by Dujo Marković and Đuro Vidaković settled in Bačka (including Subotica). After the decisive battle against the Ottomans at Senta led by Prince Eugene of Savoy on 11 September 1697, Subotica became part of the military border zone Theiss-Mieresch established by the Habsburg Monarchy. In the meantime the uprising of Francis II Rákóczi broke out, which is also known as the Kuruc War.

In the region of Subotica, Rákóczi joined battle against the Rac National Militia. Rác was a designation for the South Slavic people (mostly Serbs and Bunjevci) and they often were referred to as rácok in the Kingdom of Hungary. In a later period rácok came to mean, above all, Serbs of Orthodox religion. The Serbian military families enjoyed several privileges thanks to their service for the Habsburg Monarchy. Subotica gradually, however, developed from being a mere garrison town to becoming a market town with its own civil charter in 1743. When this happened, many Serbs complained about the loss of their privileges. The majority left the town in protest and some of them founded a new settlement just outside 18th century Subotica in Aleksandrovo, while others emigrated to Russia. In New Serbia, a new Russian province established for them, those Serbs founded a new settlement and also named it Subotica. In 1775, a Jewish community in Subotica was established.

It was perhaps to emphasise the new civic serenity of Subotica that the pious name Saint Mary came to be used for it at this time. Some decades later, in 1779, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria advanced the town's status further by proclaiming it a Free Royal Town. The enthusiastic inhabitants of the city renamed Subotica once more as Maria-Theresiopolis.

This Free Royal Town status gave a great impetus to the development of the city. During the 19th century, its population doubled twice, attracting many people from all over the Habsburg Monarchy. This led eventually to a considerable demographic change. In the first half of the 19th century, the Bunjevci had still been in the majority, but there was an increasing number of Hungarians and Jews settling in Subotica. This process was not stopped even by the outbreak of the Revolutions in the Habsburg Monarchy (1848-49).

1848/1849 Revolutions

During the 1848-49 revolution, the proclaimed borders of autonomous Serbian Vojvodina included Subotica, but Serb troops could not establish control in the region. On 5 March 1849, at the locality named Kaponja (between Tavankut and Bajmok), there was a battle between the Serb and Hungarian armies, which was won by the Hungarians.

The first newspaper in the town was also published during the 1848/49 revolution—it was called Honunk állapota ("State of Our Homeland") and was published in Hungarian by Károly Bitterman's local printing company. Unlike most Serbs and Croats who confronted the Hungarians, part of the local Bunjevci people supported the Hungarian revolution.

In 1849, after the Hungarian revolution of 1848 was defeated by the Russian and Habsburg armies, the town was separated from the Kingdom of Hungary together with most of the Bačka region, and became part of a separate Habsburg province, called Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar. The administrative centre of this new province was Timișoara. The province existed until 1860. During the existence of the voivodeship, in 1853, Subotica acquired its impressive theatre.

Hungarian administration

After the establishment of the Dual-Monarchy in 1867, there followed what is often called the "golden age" of city development of Subotica. Many schools were opened after 1867 and in 1869 the railway connected the city to the world. In 1896 an electrical power plant was built, further enhancing the development of the city and the whole region. Subotica now adorned itself with its remarkable Central European, fin de siècle architecture. In 1902 a Jewish synagogue was built in the Art Nouveau style.

Between 1849 and 1860 it was part of the Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar.[20]

Yugoslavia and Serbia

Subotica had been part of Austria-Hungary until the end of of World War I. In 1918, the city became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. As a result, Subotica became a border-town in Yugoslavia and did not, for a time, experience again the same dynamic prosperity it had enjoyed prior to World War I. However, during that time, Subotica was the third-largest city in Yugoslavia by population, following Belgrade and Zagreb.

In 1941, Yugoslavia was invaded and partitioned by the Axis Powers, and its northern parts, including Subotica, were annexed by Hungary. The annexation was not considered legitimate by the international community and the city was de jure still part of Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav government in exile received formal recognition of legitimacy as the representative of the country. On 11 April, 1941, the Hungarian troops arrived in Subotica on the grounds that the majority of the people living in the city were ethnic Hungarians, which had been part of the Kingdom of Hungary for over 600 years. During World War II, the city lost approximately 7,000 of its citizens, mostly Serbs, Hungarians and Jews. Before the war about 6,000 Jews had lived in Subotica; many of these were deported from the city during the Holocaust, mostly to Auschwitz. In April 1944, a ghetto was set up. In addition, many communists were put to death during Axis rule. In 1944, the Axis forces left the city, and Subotica became part of the new Yugoslavia. During the 1944–45 period, about 8,000 citizens (mainly Hungarians) were killed by Partisans while re-taking the city as a retribution for supporting Axis Hungary.[21][22]

In the post-war period, Subotica has gradually been modernised. During the Yugoslav and Kosovo wars of the 1990s, a considerable number of Serb refugees came to the city from Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo, while many ethnic Hungarians and Croats, as well as some local Serbs, left the region.

Cityscape

_w_Suboticy.jpg.webp)

Unique in Serbia, Subotica has the most buildings built in the art nouveau style. The City Hall (built in 1908-1910) and the Synagogue (1902) are of especially outstanding beauty. These were built by the same architects, Marcell Komor and Dezső Jakab, from Budapest, Hungary. Another exceptional example of art nouveau architecture is the actual Artistic Encounter building, which was built in 1904 by Ferenc J. Raichle.

Church buildings include the Cathedral of St. Theresa of Avila dating from 1797, the Franciscan friary dating from 1723, the Orthodox churches also from the 18th century, and the Hungarian Art Nouveau Subotica Synagogue from the early 20th century and its renovation was completed in the summer of 2019.

The historic National Theatre in Subotica, which was built in 1854 as the first monumental public building in Subotica, was demolished in 2007, although it was declared a historic monument under state protection in 1983, and in 1991 it was added to the National Register as a monument of an extraordinary cultural value. It is currently in the midst of renovation and is scheduled to open in 2017.[23]

Neighborhoods

The following are the neighborhoods of Subotica:

- Aleksandrovo

- Bajnat

- Centar

- Dudova Šuma (Radijalac)

- Gat

- Graničar

- Ker

- Kertvaroš

- Makova Sedmica

- Mali Bajmok

- Mali Radanovac

- Novi Grad

- Novo Naselje

- Prozivka

- Srpski Šor

- Teslino Naselje

- Veliki Radanovac

- Zorka

- Železničko Naselje

Suburbs and villages

The administrative area of Subotica comprises Subotica proper, the town of Palić and 17 villages. The villages are:

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 123,668 | — |

| 1953 | 126,559 | +0.46% |

| 1961 | 136,782 | +0.98% |

| 1971 | 146,770 | +0.71% |

| 1981 | 154,611 | +0.52% |

| 1991 | 150,534 | −0.27% |

| 2002 | 148,401 | −0.13% |

| 2011 | 141,554 | −0.52% |

| Source: [24] | ||

According to the 2011 census results, the city administrative area of Subotica had 141,554 inhabitants.

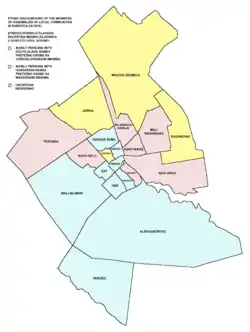

Ethnic composition

Places with either an absolute or relative Hungarian ethnic majority are: Subotica (Hungarian: Szabadka), Palić (Hungarian: Palicsfürdő), Hajdukovo (Hungarian: Hajdújárás), Bački Vinogradi (Hungarian: Bácsszőlős), Šupljak (Hungarian: Alsóludas), Čantavir (Hungarian: Csantavér), Bačko Dušanovo (Hungarian: Zentaörs), and Kelebija (Hungarian: Alsókelebia). Places with an absolute or relative Serb ethnic majority are: Bajmok, Višnjevac, Novi Žednik, and Mišićevo. Places with a relative ethnic majority Croat are: Mala Bosna, Đurđin, Donji Tavankut, Gornji Tavankut, Bikovo, Stari Žednik. Ljutovo has a relative Bunjevac ethnic majority.

The ethnic composition of the municipality:[25]

| Ethnic group | Population | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Hungarians | 50,469 | 35.65% |

| Serbs | 38,254 | 27.02% |

| Croats | 14,151 | 10.00% |

| Bunjevci | 13,553 | 9.57% |

| Yugoslavs | 3,202 | 2.26% |

| Roma | 2,959 | 2.09% |

| Montenegrins | 1,349 | 0.95% |

| Macedonians | 482 | 0.34% |

| Albanians | 383 | 0.27% |

| Muslims | 334 | 0.24% |

| Germans | 260 | 0.18% |

| Bosniaks | 216 | 0.15% |

| Rusyns | 172 | 0.12% |

| Slovenians | 169 | 0.12% |

| Slovaks | 158 | 0.11% |

| Gorani | 151 | 0.11% |

| Others | 15,292 | 10.80% |

| Total | 141,554 |

Languages

Languages spoken in Subotica administrative area:[26]

- Serbian = 63,412 (44.80%)

- Hungarian = 50,621 (35.76%)

- Bunjevac = 6,313 (4.46%)

- Croatian = 5,758 (4.07%)

- Others

Serbian is the most employed language in daily life, but Hungarian is also used by over one third of the population in their daily conversations. Both languages are also widely employed in commercial and official signage [27]

Religion

Religion in the Subotica administrative area as of the 2011 census:[26]

- Roman Catholic = 81,532 (57.60%)

- Orthodox = 39,333 (27.79%)

- Muslim = 2,756 (1.95%)

- Protestant = 2,372 (1.68%)

- Judaism = 89 (0.001%)

Subotica is the centre of the Roman Catholic diocese of the Bačka region. The Subotica area has the highest concentration of Catholics in Serbia. 57% of the city's population are Catholic. There are eight Catholic parish churches, a Franciscan spiritual centre (the city has communities of both Franciscan friars and Franciscan nuns), a female Dominican community, and two congregations of Augustinian religious sisters. The diocese of Subotica has the only Catholic secondary school in Serbia (Paulinum).

When the nuns' orphanage and children's home in Blato, Korčula (present-day Croatia) had exhausted the food and funds needed for helping poor and hungry children, Marija Petković (later known as Blessed Mary of Jesus Crucified Petković), went to Bačka, whose apostolic seat is Subotica, to solicit help for orphans and widows. Bishop Ljudevit Lajčo Budanović asked Petković to found monasteries of her Order in Subotica and neighbourhood, so the locals could benefit spiritually from the instruction of the nuns of her Order.[28] She learned that Bačka had many poor and abandoned children. In 1923, she opened Kolijevka, a children's home in Subotica. The home still exists but is no longer run by nuns.

Among other Christian communities, the members of the Serbian Orthodox Church are the most numerous. There are two Orthodox church buildings in the city. Orthodox Christians in Subotica belong to the Eparchy of Bačka of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Subotica has two Protestant churches as well, Lutheran and Calvinist. The Jewish community of Subotica is the third largest in Serbia, after those in Belgrade and Novi Sad. About 1000 (of the 6,000 pre-WWII Jews of Subotica) survived the Holocaust. According to the 2011 census, fewer than 90 Jews remained in Subotica as of 2011.[26]

Politics

Results of 2016 local elections in Subotica municipality:[29]

- SNS coalition: 35.6%

- Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians: 15%

- Movement for Civic Subotica: 12.9%

- Democratic Party: 8.5%

- League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina: 5.7%

After the elections, a coalition led by Serbian Progressive Party and Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians formed the local municipal government. Bogdan Laban, from Serbian Progressive Party, was elected mayor.

- Coat of arms

The original coat of arms and current medium coat of arms have an outlining latin inscription of Civitatis Maria Theresiopolis, Sigillum Liberæque Et Regiæ, translated as Seal of the Free and Royal City of Maria Theresiopolis.

Economy

The area around Subotica is mainly farmland but the city itself is an important industrial and transportation centre in Serbia. Due to the surrounding farmlands Subotica has famous food producer industries in the country, including such brands as the confectionery factory "Pionir", "Fidelinka" the cereal manufacturer, "Mlekara Subotica" a milk producer and "Simex" producer of strong alcohol drinks.

There are a number of old socialistic industries that survived the transition period in Serbia. The biggest one is the chemical fertilizer factory "Azotara" and the rail wagon factory "Bratstvo". Currently the biggest export industry in town is the "Siemens Subotica" wind generators factory and it is the biggest brownfield investment so far. The other big companies in Subotica are: Fornetti, ATB Sever and Masterplast. More recent companies to come to Subotica include Dunkermotoren and NORMA Group. Tourism is important. In the past few years, Palić has been famous for the Palić Film Festival. Subotica is a festival city, hosting more than 17 festivals over the year.

As of September 2017, Subotica has one of 14 free economic zones established in Serbia.[30]

In 2020 construction of a new aqua park with ten pools and wellness and spa sections was underway in Palić.[31]

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[32]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 632 |

| Mining and quarrying | 5 |

| Manufacturing | 14,481 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 360 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 570 |

| Construction | 1,829 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 7,337 |

| Transportation and storage | 3,136 |

| Accommodation and food services | 1,802 |

| Information and communication | 1,056 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 621 |

| Real estate activities | 127 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 1,503 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 1,088 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 1,997 |

| Education | 2,596 |

| Human health and social work activities | 3,416 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 653 |

| Other service activities | 984 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 1,438 |

| Total | 45,631 |

Education

Secondary schools

- Polytechnic school, Surveying and Construction, Typography, Forestry and Wood Processing

- Teachers' College, founded in 1689, the oldest college in the country and region

- "Svetozar Marković" grammar school

- "Dezső Kosztolányi" Philological grammar school

- "MEŠC" Electro-mechanical school, recently renamed to "Tehnička Škola - Subotica" (en. "Technical School")

- "Bosa Milićević" School of Economics

- "Lazar Nešić" School of Chemistry

- "Medicinska Škola" Medical School

4 953 students studied in the city in the year 2020/21 in the secondary education. 1 626 students chose Hungarian speaking classes (32.8%), 209 students chose Croatian classes while 3 118 students studied in Serbian language.<http://opendata.mpn.gov.rs/index.php?page=ustanove_registar>

Historical schools (1920 to 1941)

Sport

Subotica has one major football stadium, the Subotica City Stadium, indoor arena and indoor swimming pool. The local football team is Spartak and plays in the Serbian SuperLiga, the country's primary football competition.

Media

Newspapers and magazines published in Subotica:

- Magyar Szó, daily newspaper in Hungarian, founded 1944, published in Subotica since 2006.

- Subotičke novine, main weekly newspaper in Serbian.

- Bunjevačke novine, in Bunjevac.

- Hrvatska riječ, in Croatian.

- Zvonik, in Croatian

Infrastructure

A1 motorway connects the city with Novi Sad and Belgrade to the south and, across the border with Hungary, with Szeged to the north. It runs alongside the Budapest–Belgrade railway, which connects it to major European cities.

The city used to have a tram system, the Subotica tram system, but it was discontinued in 1974. The Subotica tram, put into operation in 1897, ran on electricity from the start. While neighbouring cities' trams at this date were often still horse-drawn, this gave the Subotica system an advantage over other municipalities including Belgrade, Novi Sad, Zagreb, and Szeged. Its existence was important for the citizens of Subotica, as well as tourists who came to visit. Subotica has since developed a bus system. The Subotica buses transport people via nine city, six suburban, and ten interurban, as well as two international lines of bus operations. Per year the buses travel some 4.7 million kilometres, and carry about ten million people.

The city is served by Subotica Airport; its runway is too short for airliners, limiting usage to mostly recreational aviation. Southwest of the city there is a 218.5 metres tall guyed mast for FM-/TV-broadcasting. It is the tallest of its kind in Serbia and one of the tallest in the region.

Famous citizens

- Branimir Aleksić, football player and member of the Serbia national football team

- Sava Babić (1934–2012), writer, translator and university professor

- Géza Csáth (1887–1919), a tragic physician-writer

- Gyula Cseszneky (born 1914), Hungarian, poet, voivode

- Sreten Damjanović (born 1946), wrestler

- Oliver Dulić (born 1975), politician

- Vlatko Dulić (born 1943), actor

- Yehuda Elkana, born 1934. Israeli philosopher of science

- Zoran Kalinić (born 1958), table tennis champion

- Danilo Kiš (1935–1989), writer

- Juci Komlós (born 1919), Hungarian actress

- Dezső Kosztolányi (1885–1936), Hungarian poet and prose-writer

- Zoran Kuntić, a former Serbian professional footballer

- Félix Lajkó (born 1974), a "world music" violinist and composer

- Péter Lékó (born 1979), Hungary's number one chess player

- Szilveszter Lévai (born 1945), Hungarian composer

- Aleksandar Lifka (1880–1952), a central-European cinematographer

- Manojle Đorđević (born 1979), Professional actor and rope access master

- Bela Lugosi (1882–19569), actor

- Refik Memišević (born 1956), wrestle champion

- Đula Mešter, born in 1972, volleyball player and Olympic champion

- Jovan Mikić Spartak (1914–1944), the leader of the Partisans in Subotica, and a national hero who was killed in 1944

- Tihomir Ognjanov, a former Serbian footballer who was part of Yugoslavia national football team

- Momir Petković (born 1953), wrestling champion

- Bojana Radulović (born 1973), handball player

- Eva Ras (born 1941), actress, painter, and writer

- Magdolna Rúzsa (born 1985), Hungarian pop singer

- Ivan Sarić (1876–1966), aviation pioneer and cyclist

- Tibor Sekelj (Tibor Székely) (1912–1988), explorer, esperantist, writer

- John Simon (1925–2019), American theatre critic

- György Sztantics (1878–1918), a racewalking champion at the Intercalated Games

- Đorđe Tutorić, Serbian professional football player

- Davor Štefanek (born 1985), Serbian wrestler and Olympic champion

- Boris Malagurski (born 1988), Serbian Canadian Film Director, Producer, and TV Host

- Nikola Kalinić (born 1991), Serbian basketball player, silver medalist at the Olympics and the FIBA World Cup

- Mirna Radulović (born 1992), Serbian singer who represented Serbia in the Eurovision Song Contest 2013 as part of Moje 3

- Itzchak Tarkay (1935 – June 3, 2012) was an Israeli artist

International cooperation

- Subotica is a pilot city of the Council of Europe and the EU Intercultural cities programme.[33]

Twin towns - Sister cities

Subotica is twinned with the following cities:

|

See also

References

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia: Comparative Overview of the Number of Population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011, Data by settlements" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- "Borovszky - Magyarország vármegyéi és városai". mek.oszk.hu.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2011-03-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ["Kommunalpolitische ] Vereinigung (Municipal Political Association, the sub-organization of the Christian Democratic Union and the Christlich-Soziale Union of Germany), Serbien Reader - Kleiner Wegweiser für den Political Visit (Serbia Reader - small guide for political visit), Serbien/Montenegro, unsere neuen europäischen Nachbarn (Serbia/Montenegro, our new European neighbors), from March 2009, edited by Christian Passin and Sabine Schiftar, page 76" Check

|url=value (help) (PDF) (in German). By Kommunalpolitische Vereingung (www.kpv.at), Vienna. Retrieved 21 January 2013. - "Slavistische Studien Bücher - Folge 10 (Slavic Study Books - Episode 10), Handbuch der Südosteuropa-Linguistik (Manual of the Southeast Europe Linguistics), edited by Üwe Hinrichs and Uwe Büttner, page 687" (in German). Harrassowitz Verlag. 1999. ISBN 9783447039390. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "Ungarisch - ein goldener Käfig?(Hungarian - a golden cage?)" (in German). By Die Zeit. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "Ein goldener Käfig von Ádám Nádasdy (A golden cage by Ádám Nádasdy), page 2" (PDF) (in German). By the Hungarian Book Foundation by Ádám Nádasdy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "Szabadka – Magyar Katolikus Lexikon". lexikon.katolikus.hu.

- Article in "Bunjevačke novine", number 8, February 2006. Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- "Subotica, North Bačka, Serbia Monthly Weather Forecast - weather.com". Weather Channel. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- "Map". catyline.com.

- "[Projekat Rastko] Nikola Tasic: Eneolitske kulture centralnog i zapadnog Balkana". www.rastko.rs.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2011-02-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link),

- eliznik. "South East Europe history - 1,800 BC map". www.eliznik.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-03-25. Retrieved 2013-01-14.

- Borovszky Samu: Magyarország vármegyéi és városai, Bács-Bodrog vármegye I-II. kötet, Apolló Irodalmi és Nyomdai Részvénytársaság, 1909.

- Officially known as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes until 1929

- Known as Democratic Federal Yugoslavia until 1945

- Sanjak of Segedin

- "Subotica | Hrvatska enciklopedija". www.enciklopedija.hr. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- Mészáros Sándor: Holttá nyilvánítva - Délvidéki magyar fátum 1944–45, I-II, Hatodik Síp Alapítvány, Budapest 1995.

- Cseres Tibor: Vérbosszú Bácskában, Magvető kiadó, Budapest 1991.

- "Radovi na rekonstrukciji Narodnog pozorišta u Subotici". Gradjevinarstvo.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- "Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The Use of Hungarian and Serbian in the City of Szabadka/Subotica: An Empirical Study". Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- M. Stantić. Blessed Marija Petković Archived 19 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine M. Stantić: Zauzimanje za siromahe - karizma danas, marijapropetog.hr; accessed 5 February 2016. (in Croatian)

- "SNS osvojio najviše glasova u Subotici - Srbija izbori 2018". www.srbijaizbori.com.

- Mikavica, A. (3 September 2017). "Slobodne zone mamac za investitore". politika.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- symbolic. "Do kraja godine biće završen akva-park na Paliću" (in Serbian). Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- "MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA, 2019" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Intercultural Cities - Home". Intercultural cities programme.

Sources

- Recent (2002) statistical information comes from the Serbian statistical office.

- Ethnic statistics: "КОНАЧНИ РЕЗУЛТАТИ ПОПИСА 2002" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25. (477 KB), САОПШTЕЊЕ СН31, брoј 295 • год. LII, 24.12.2002, YU ISSN 0353-9555. Accessed 17 January 2006. On page 6–7, Становништво према националној или етничкој припадности по попису 2002. Statistics can be found on the lines for "Суботица" (Subotica).

- Language and religion statistics: Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u 2002, ISBN 86-84433-02-5. Accessed 17 January 2006. On page 11–12: СТАНОВНИШТВО ПРЕМА ВЕРОИСПОВЕСТИ, СТАНОВНИШТВО ПРЕМА МАТЕРЊЕМ ЈЕЗИКУ. Statistics can be found on the lines for "Суботица" (Subotica).

- Ferdinand, S. and F. Komlosi. 2017. The Use of Hungarian and Serbian in the City of Szabadka/Subotica: An Empirical Study, Hungarian Cultural Studies, Volume 10. Accessed 8 September 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Subotica. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Subotica. |