Rhaphidophoridae

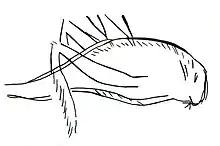

The orthopteran family Rhaphidophoridae of the suborder Ensifera has a worldwide distribution.[1] Common names for these insects include the cave wētā, cave crickets, camelback crickets, camel crickets, spider crickets (sometimes shortened to "criders", or "land shrimp" or "sprickets",[2]) and sand treaders. Those occurring in New Zealand, Australia, and Tasmania are typically referred to as jumping or cave wētā.[3] Most are found in forest environments or within caves, animal burrows, cellars, under stones, or in wood or similar environments.[4] All species are flightless and nocturnal, usually with long antennae and legs.[3] More than 1100 species of Rhaphidophoridae are described.[1]

| Rhaphidophoridae | |

|---|---|

| |

| A cricket of uncertain species | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Orthoptera |

| Suborder: | Ensifera |

| Superfamily: | Rhaphidophoroidea Walker, 1869 |

| Family: | Rhaphidophoridae Walker, 1869 |

| Subfamilies and genera | |

The well-known field crickets are from a different superfamily (Grylloidea) and only look vaguely similar, while members of the family Tettigoniidae may look superficially similar in body form.

Description

Most cave crickets have very large hind legs with "drumstick-shaped" femora and equally long, thin tibiae, and long, slender antennae. The antennae arise closely and next to each other on the head. They are brownish in color and rather humpbacked in appearance, always wingless, and up to 5 cm (2.0 in) long in body and 10 cm (3.9 in) for the legs. The bodies of early instars may appear translucent.

As their name suggests, cave crickets are commonly found in caves or old mines. However, species are also known to inhabit other cool, damp environments such as rotten logs, stumps and hollow trees, and under damp leaves, stones, boards, and logs.[4][5] Occasionally, they prove to be a nuisance in the basements of homes in suburban areas, drains, sewers, wells, and firewood stacks. One has become a tramp species from Asia and is now found in hothouses in Europe and North America. Some reach into alpine areas and live close to permanent ice, the Mount Cook "flea" (Pharmacus montanus) and its relatives in New Zealand.[6]

Subfamilies and genera

Aemodogryllinae

Genera include:

- tribe Aemodogryllini Jacobson, 1905 - Asia (Korea, Indochina, Russia, China), Europe

- Diestrammena Brunner von Wattenwyl, 1888

- Tachycines Adelung, 1902

- tribe Diestramimini Gorochov, 1998 - India, southern China, Indo-China

- Diestramima Storozhenko, 1990

- Gigantettix Gorochov, 1998

Ceuthophilinae

cave crickets, camel crickets and sand treaders: North America

- tribe Argyrtini Saussure & Pictet, 1897

- Anargyrtes Hubbell, 1972

- Argyrtes Saussure & Pictet, 1897

- Leptargyrtes Hubbell, 1972

- tribe Ceuthophilini Tepper, 1892

- Ceuthophilus Scudder, 1863

- Macrobaenetes Tinkham, 1962

- Rhachocnemis Caudell, 1916

- Styracosceles Hubbell, 1936

- Typhloceuthophilus Hubbell, 1940

- Udeopsylla Scudder, 1863

- Utabaenetes Tinkham, 1970

- tribe Daihiniini Karny, 1930

- Ammobaenetes Hubbell, 1936

- Daihinia Haldeman, 1850

- Daihinibaenetes Tinkham, 1962

- Daihiniella Hubbell, 1936

- Daihiniodes Hebard, 1929

- Phrixocnemis Scudder, 1894

- tribe Hadenoecini Ander, 1939 - North America

- Euhadenoecus Hubbell, 1978

- Hadenoecus Scudder, 1863

- tribe Pristoceuthophilini Rehn, 1903

- Exochodrilus Hubbell, 1972

- Farallonophilus Rentz, 1972

- Pristoceuthophilus Rehn, 1903

- Salishella Hebard, 1939

Dolichopodainae

cave crickets: southern Europe, western Asia

- Dolichopoda Bolivar, 1880

Gammarotettiginae

Auth. Karny, 1937 - N. America

- tribe Gammarotettigini Karny, 1937

- Gammarotettix Brunner von Wattenwyll, 1888

Macropathinae

- tribe Macropathini Karny, 1930 - Australia, Chile, New Zealand, Falkland Islands

Pachyrhamma edwardsii from New Zealand

Pachyrhamma edwardsii from New Zealand- Australotettix Richards, 1964

- Cavernotettix Richards, 1966

- Dendroplectron Richards, 1964 – New Zealand

- Heteromallus Brunner von Wattenwyll, 1888

- Insulanoplectron Richards, 1970 – New Zealand

- Ischyroplectron Hutton, 1896 – New Zealand

- Isoplectron Hutton, 1896 – New Zealand

- Macropathus Walker, 1869 – New Zealand

- Maotoweta Johns & Cook, 2014 – New Zealand

- Micropathus Richards, 1964 – Australia

- Miotopus Hutton, 1898 - New Zealand

- Neonetus Brunner von Wattenwyll, 1888 – New Zealand

- Notoplectron Richards, 1964

- Novoplectron Richards, 1966 – New Zealand

- Novotettix Richards, 1966

- Pachyrhamma Brunner von Wattenwyll, 1888 – New Zealand

- Pallidoplectron Richards, 1958 – New Zealand

- Pallidotettix Richards, 1968

- Paraneonetus Salmon, 1958 – New Zealand

- Parudenus Enderlein, 1910

- Parvotettix Richards, 1968

- Petrotettix Richards, 1972 – New Zealand

- Pharmacus Pictet & Saussure, 1893 – New Zealand

- Pleioplectron Hutton, 1896 – New Zealand

- Setascutum Richards, 1972 – New Zealand

- Spelaeiacris Peringuey, 1916

- Speleotettix Chopard, 1944

- Tasmanoplectron Richards, 1971

- Udenus Brunner von Wattenwyll, 1900

- Weta Chopard, 1923 – New Zealand

- tribe Talitropsini Gorochov, 1988

- Talitropsis Bolivar, 1882 – New Zealand

Rhaphidophorinae

- tribe Rhaphidophorini Walker, 1869 - India, southern China, Japan, Indo-China, Malesia, Australasia

- Diarhaphidophora Gorochov, 2012

- Eurhaphidophora Gorochov, 1999

- Minirhaphidophora Gorochov, 2002

- Neorhaphidophora Gorochov, 1999

- Pararhaphidophora Gorochov, 1999

- Rhaphidophora (insect) Serville, 1838

- Sinorhaphidophora Qin, Jiang, Liu & Li, 2018

- Stonychophora Karny, 1934

Troglophilinae

cave crickets: Mediterranean

- Troglophilus Krauss, 1879

Tropidischiinae

camel crickets: Canada

- Tropidischia Scudder, 1869

An as-yet-unnamed genus was discovered within a cave in Grand Canyon–Parashant National Monument, on the Utah/Arizona border, in 2005. Its most distinctive characteristic is that it has functional grasping cerci on its posterior.[7]

Ecology

Their distinctive limbs and antennae serve a double purpose. Typically living in a lightless environment, or active at night, they rely heavily on their sense of touch, which is limited by reach. While they have been known to take up residence in the basements of buildings,[8] many cave crickets live out their entire lives deep inside caves. In those habitats, they sometimes face long spans of time with insufficient access to nutrients. Given their limited vision, cave crickets often jump to avoid predation. Those species of Rhaphidophoridae that have been studied are primarily scavengers, eating plant, animal and fungi material.[8] Although they look intimidating, they are completely harmless.[9]

The group known as "sand treaders" is restricted to sand dunes, and are adapted to live in this environment. They are active only at night, and spend the day burrowed into the sand, to minimize water loss. In the large sand dunes of California and Utah, they serve as food for scorpions and at least one specialized bird, LeConte's thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei). The thrasher roams the dunes looking for the tell-tale debris of the diurnal hiding place and excavates the sand treaders (range of bird is in the Mojave and Colorado Deserts in U.S.).

Interactions with humans

Cave and camel crickets are of little economic importance except as a nuisance in buildings and homes, especially basements. They are usually "accidental invaders" that wander in from adjacent areas. They may reproduce indoors, seen in dark, moist conditions, such as a basement, shower, or laundry area, as well as organic debris (e.g. compost heaps) to serve as food. They are fairly common invaders of homes in Hokkaido and other chilly regions in Japan. They are called kamado-uma or colloquially benjo korogi (literally "toilet cricket").

A representation of a female from the Troglophilus genus has been found engraved on a bison bone in the Cave of the Trois-Frères,[10] showing that they were likely already present around humans, maybe as pests, in caves inhabited by prehistoric populations in the Magdalenian.

References

- Eades, David C. (2016). "Orthoptera Species File".

- Ambrose, Kevin (2016-11-08). "Spider crickets: The bugs you don't want in your house this fall". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Allegrucci, Giuliana; Trewick, Steve A.; Fortunato, Angela; Carchini, Gianmaria; Sbordoni, Valerio (2010-07-01). "Cave Crickets and Cave Weta (Orthoptera, Rhaphidophoridae) from the Southern End of the World: A Molecular Phylogeny Test of Biogeographical Hypotheses". Journal of Orthoptera Research. 19 (1): 121–130. doi:10.1665/034.019.0118. ISSN 1082-6467. S2CID 86260199.

- Richards, Aola (1987). "Distribution and relationships of the Australian Rhaphidophoridae (Orthoptera)". In Baccetti, Baccio (ed.). Evolutionary Biology of Orthopteroid Insects. Chichester, West Sussex: Halstead Press. pp. 438–449. ISBN 0745802087.

- Hegg, Danilo; Morgan-Richards, Mary; Trewick, Steven A. (2019). "Diversity and distribution of Pleioplectron Hutton cave wētā (Orthoptera: Rhaphidophoridae: Macropathinae), with the synonymy of Weta Chopard and the description of seven new species". European Journal of Taxonomy. 0 (577). doi:10.5852/ejt.2019.577. ISSN 2118-9773.

- Trewick (2015). "weta geta".

- "New genus of cricket found in Arizona cave". Live Science. 5 May 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- Richards, Aola (1961). "Some observations on New Zealand Cave-Wetas". Tuatara. 9 (2): 80–83.

- Rick Steinau. "Camelback Crickets". Ask the Exterminator.

- Bégouën, Henri (1929). "Sur quelques objets nouvellement découverts dans les grottes des Trois Frères (Montesquieu-Avantès, Ariège)". Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique de France (in French). 26 (3): 188–196. doi:10.3406/bspf.1929.6692. ISSN 1760-7361..

External links

Data related to Rhaphidophoridae at Wikispecies

Data related to Rhaphidophoridae at Wikispecies Media related to Rhaphidophoridae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rhaphidophoridae at Wikimedia Commons