Mole cricket

Mole crickets are members of the insect family Gryllotalpidae, in the order Orthoptera (grasshoppers, locusts, and crickets). Mole crickets are cylindrical-bodied insects about 3–5 cm (1.2–2.0 in) long as adults, with small eyes and shovel-like fore limbs highly developed for burrowing. They are present in many parts of the world and where they have arrived in new regions, may become agricultural pests.

| Mole cricket | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gryllotalpa brachyptera | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Orthoptera |

| Suborder: | Ensifera |

| Infraorder: | Gryllidea |

| Superfamily: | Gryllotalpoidea |

| Family: | Gryllotalpidae Saussure, 1870 |

| |

| Distribution of Gryllotalpa, Scapteriscus, Neocurtilla | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

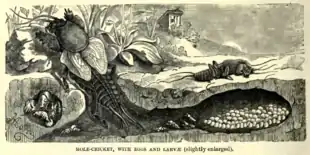

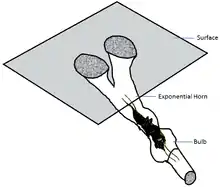

Mole crickets have three life stages: eggs, nymphs, and adults. Most of their lives in these stages are spent underground, but adults have wings and disperse in the breeding season. They vary in their diet: some species are herbivores, mainly feeding on roots; others are omnivores, including worms and grubs in their diet; and a few are largely predatory. Male mole crickets have an exceptionally loud song; they sing from a burrow that opens out into the air in the shape of an exponential horn. The song is an almost pure tone, modulated into chirps. It is used to attract females, either for mating, or for indicating favourable habitats for them to lay their eggs.

In Zambia, mole crickets are thought to bring good fortune, while in Latin America, they are said to predict rain. In Florida, where Neoscapteriscus mole crickets are not native, they are considered pests, and various biological controls have been used. Gryllotalpa species have been used as food in West Java, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

Description

Mole crickets vary in size and appearance, but most of them are of moderate size for an insect, typically between 3.2 and 3.5 cm (1.3 and 1.4 in) long as adults. They are adapted for underground life and are cylindrical in shape and covered with fine, dense hairs. The head, fore limbs, and prothorax are heavily sclerotinised, but the abdomen is rather soft.[1] The head bears two threadlike antennae and a pair of beady eyes.[2] The two pairs of wings are folded flat over the abdomen; in most species, the fore wings are short and rounded and the hind wings are membranous and reach or exceed the tip of the abdomen; however, in some species, the hind wings are reduced in size and the insect is unable to fly. The fore legs are flattened for digging, but the hind legs are shaped somewhat like the legs of a true cricket; however, these limbs are more adapted for pushing soil, rather than leaping, which they do rarely and poorly. The nymphs resemble the adults apart from the absence of wings and genitalia; the wing pads become larger after each successive moult.[3]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The Gryllotalpidae are a monophyletic group in the order Orthoptera (grasshoppers, locusts, and crickets). Cladistic analysis of mole cricket morphology in 2015 identified six tribes, of which four were then new: Indioscaptorini (Scapteriscinae), Triamescaptorini, Gryllotalpellini and Neocurtillini (Gryllotalpinae), and two existing tribes, Scapteriscini and Gryllotalpini, are revised.[4] The group name is derived straightforwardly from Latin gryllus, cricket, and talpa, mole.[5]

| Subfamily | Image | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scapteriscinae |  | Neoscapteriscus vicinus | Extant |

| Gryllotalpinae | _(16643378886).jpg.webp) | Gryllotalpa africana | Extant |

| Marchandiinae† | Cretaceous of France and Brazil |

Within the extant subfamilies, genera include:[6]

Gryllotalpinae

- tribe Gryllotalpellini Cadena-Castañeda, 2015 (South America)

- Gryllotalpella

- tribe Gryllotalpini Leach, 1815 (World-wide)

- tribe Neocurtillini Cadena-Castañeda, 2015 (Americas)

- Leptocurtilla

- Neocurtilla

- tribe Triamescaptorini Cadena-Castañeda, 2015 (New Zealand)

- tribe incertae sedis

- †genus Pterotriamescaptor

- †genus Burmagryllotalpa[7] Burmese amber, Myanmar, Cenomanian

Scapteriscinae

- tribe Indioscaptorini Cadena-Castañeda, 2015 (Indian Subcontinent)

- Indioscaptor

- tribe Scapteriscini Zeuner, 1939 (Americas)

†subfamily Marchandiinae

- †Archaeogryllotalpoides Martins-Neto 1991 Crato Formation, Brazil, Aptian

- †Cratotetraspinus Martins-Neto 1997 Crato Formation, Brazil, Aptian

- †Marchandia Perrichot et al. 2002 Charentese amber, France, Cenomanian

- †Palaeoscapteriscops Martins-Neto 1991 Crato Formation, Brazil, Aptian

Incertae sedis

- †Tresdigitus rectanguli Xu, Fang & Wang, 2020[8] Burmese amber, Myanmar, Cenomanian

Mole cricket fossils are rare. A stem group fossil, Cratotetraspinus, is known from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil.[9] Two specimens of Marchandia magnifica in amber have been found in the Lower Cretaceous of Charente-Maritime in France.[10] They are somewhat more abundant in the Tertiary amber of the Baltic and Dominican regions; impressions are found in Europe and the American Green River Formation.[11]

_(13977429463).jpg.webp)

Convergent evolution

Mole crickets are not closely related to the "pygmy mole crickets", the Tridactyloidea, which are in the grasshopper suborder Caelifera rather than the cricket suborder Ensifera. The two groups, and indeed their resemblance in form to the mammalian mole family Talpidae with their powerful front limbs, form an example of convergent evolution, both developing adaptations for burrowing.[12]

Behavior

Adults of most species of mole cricket can fly powerfully, if not with agility, but males do so infrequently. The females typically take wing soon after sunset, and are attracted to areas where males are calling, which they do for about an hour after sunset. This may be to mate, or they may be influenced by the suitability of the habitat for egg-laying, as demonstrated by the number of males present and calling in the vicinity.[1]

Life cycle

Mole crickets undergo incomplete metamorphosis; when nymphs hatch from eggs, they increasingly resemble the adult form as they grow and pass through a series of up to 10 moults. After mating, a period of 1-2 weeks may occur before the female starts laying eggs. She burrows into the soil to a depth of 30 cm (12 in), (72 cm (28 in) has been seen in the laboratory), and lays a clutch of 25 to 60 eggs. Neoscapteriscus females then retire, sealing the entrance passage, but in Gryllotalpa and Neocurtilla species, the female has been observed to remain in an adjoining chamber to tend the clutch. Further clutches may follow over several months, according to species. Eggs must be laid in moist ground, and many nymphs die because of insufficient moisture in the soil. The eggs hatch in a few weeks, and as they grow, the nymphs consume a great deal of plant material either underground or on the surface. The adults of some species of mole crickets may move as far as 8 km (5.0 mi) during the breeding season. Mole crickets are active most of the year, but overwinter as nymphs or adults in cooler climates, resuming activity in the spring.[1]

Burrowing

Mole crickets live almost entirely below ground, digging tunnels of different kinds for the major functions of life, including feeding, escape from predators, attracting a mate (by singing), mating, and raising of young.[13]

Their main tunnels are used for feeding and for escape; they can dig themselves under ground very rapidly, and can move along existing tunnels at high speed both forwards and backwards. Their digging technique is to force the soil to either side with their powerful, shovel-like fore limbs, which are broad, flattened, toothed, and heavily sclerotised (the cuticle is hardened and darkened).[13]

Males attract mates by constructing specially shaped tunnels in which they sing.[13] Mating takes place in the male's burrow; the male may widen a tunnel to make room for the female to mount, though in some species, mating is tail-to-tail.[13] Females lay their eggs either in their normal burrows or in specially dug brood chambers, which are sealed when complete in the case of the genus Neoscapteriscus[13] or not sealed in the case of genera Gryllotalpa and Neocurtilla.

Song

Male mole crickets sing by stridulating, always under ground.[14] In Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa, the song is based on an almost pure tone at 3.5 kHz, loud enough to make the ground vibrate 20 cm all round the burrow; in fact, the song is unique in each species. In G. gryllotalpa, the burrow is somewhat roughly sculpted; in G. vineae, the burrow is smooth and carefully shaped, with no irregularities larger than 1 mm. In both species, the burrow has two openings at the soil surface; at the other end is a constriction, then a resonating bulb, and then an escape tunnel. A burrow is used for at least a week. The male positions himself head down with his head in the bulb, and his tail is near the fork in the tunnel.[14][16]

Mole crickets stridulate like other crickets by scraping the rear edge of the left fore wing, which forms a plectrum, against the lower surface of the right fore wing, which has a ratchet-like series of asymmetric teeth; the more acute edges face backwards, as do those of the plectrum. The plectrum can move forward with little resistance, but moving it backwards makes it catch each tooth, setting up a vibration in both wings. The sound-producing stroke is the raising (levation) of the wings. The resulting song resembles the result of modulating a pure tone with a 66-Hz wave to form regular chirps. In G. vineae, the wing levator muscle, which weighs 50 mg, can deliver 3.5 milliwatts of mechanical power; G. gryllotalpa can deliver about 1 milliwatt. G. vineae produces an exceptionally loud song from half an hour after sunset, continuing for an hour; it can be heard up to 600 m away. At a distance of 1 m from the burrow, the sound has a mean power over the stridulation cycle up to 88 decibels; the loudest recorded peak power was about 92 decibels; at the mouths of the burrow, the sound reaches around 115 decibels. G. gryllotalpa can deliver a peak sound pressure of 72 decibels and a mean of about 66 decibels. The throat of the horn appears to be tuned (offering low inductive reactance), making the burrow radiate sound efficiently; the efficiency increases when the burrow is wet and absorbs less sound. Mole crickets are the only insects that construct a sound-producing apparatus. Given the known sensitivity of a cricket's hearing (60 decibels), a night-flying G. vineae female should be able to detect the male's song at a range of 30 m; this compares to about 5 m for a typical Gryllus cricket that does not construct a burrow.[14]

The loudness of the song is correlated with the size of the male and the quality of the habitat, both indicators of male attractiveness. The loudest males may attract 20 females in one evening, while a quieter male may attract none. This behaviour enables acoustic trapping; females can be trapped in large numbers by broadcasting a male's song very loudly.[17][18]

Food

Mole crickets vary in their diets; some like the tawny mole cricket are herbivores, others are omnivores, feeding on larvae, worms, roots, and grasses, and others like the southern mole cricket are mainly predacious.[19][20] They leave their burrows at night to forage for leaves and stems, which they drag underground before consumption, as well as consuming roots underground.[3]

Predators, parasites, and pathogens

Besides birds, toads, and insectivorous mammals, the predators of mole crickets include subterranean assassin bugs, wolf spiders, and various beetles.[21] The South American nematode Steinernema scapterisci kills Neocapteriscus mole crickets by introducing bacteria into their bodies, causing an overwhelming infection.[22] Steinernema neocurtillae is native to Florida and attacks native Neocurtilla hexadactyla mole crickets.[23] Parasitoid wasps of the genus Larra (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae) attack mole crickets, the female laying an egg on the external surface of the mole cricket, and the larva developing externally on the mole cricket host. Ormia depleta (Diptera: Tachinidae) is a specialized parasitoid of mole crickets in the genus Neoscapteriscus; the fly's larvae hatch from eggs inside her abdomen; she is attracted by the call of the male mole cricket and deposits a larva or more on any mole cricket individual (just as many females as males) with which she comes in contact.[24] Specialist predators of mole cricket eggs in China and Japan include the bombardier beetle Stenaptinus jessoensis, whereas in South America, they include the bombardier beetle Pheropsophus aequinoctialis (Coleoptera: Carabidae); the adult beetle lays eggs near the burrows of mole crickets, and the beetle larvae find their way to the egg chamber and eat the eggs.[25] Fungal diseases can devastate mole cricket populations during winters with sudden rises of temperature and thaws.[26] The fungus Beauveria bassiana can overwhelm adult mole crickets[27] and several other fungal, microsporidian, and viral pathogens have been identified.[21] Mole crickets evade predators by living below ground, and vigorously burrowing if disturbed at the surface. As a last-ditch defence, they eject a foul-smelling brown liquid from their anal glands when captured;[28] they can also bite.[29]

Distribution

Mole crickets are relatively common, but because they are nocturnal and spend nearly all their lives under ground in extensive tunnel systems, they are rarely seen. They inhabit agricultural fields and grassy areas. They are present in every continent except Antarctica; by 2014, 107 species had been described and more species are likely to be discovered, especially in Asia. Neoscapteriscus didactylus is a pest species, originating in South America; it has spread to the West Indies and New South Wales in Australia.[30] Gryllotalpa africana is a major pest in South Africa; other Gryllotalpa species are widely distributed in Europe, Asia, and Australia.[31] They are native to Britain (as to Western Europe), but the former population of G. gryllotalpa may now be extinct in mainland Britain,[32] surviving in the Channel Islands.[33]

Invasive mole crickets and their biological control

Invasive species are those that cause harm in their newly occupied area, where biological control may be attempted. The first-detected invasive mole cricket species was Neoscapteriscus didactylus, a South American species reported as a pest in St. Vincent, West Indies, as early as 1837; by 1900, it was a major agricultural pest in Puerto Rico. It had probably slowly expanded its range northwards, island by island, from South America.[30] The only biological control program against N. didactylus was in Puerto Rico, and it succeeded in establishing the parasitoid wasp Larra bicolor from Amazonian Brazil.[34] In 2001, N. didactylus in Puerto Rico seemed to be a pest only in irrigated crops and turf. Small-scale experimental applications of the nematode Steinernema scapterisci were made in irrigated turf, but survival of the nematode was poor.[35] Very much later, this same species was reported as a pest in Queensland, Australia, presumably arriving by ship or plane.[36] The next-detected invasive species was in the late 19th century in Hawaii, probably by ship. It was named as Gryllotalpa africana, but much later as perhaps G. orientalis. It was not identified as Gryllotalpa krishnani until 2020.[37] <ref=Frank J.H. 2020. The identity of the adventive Gryllotalpa Latreille species (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) in Hawaii, with illustration of male genitalia of G. orientalis Burmeister. Insecta Mundi 0747: 1-8.</ref> It attacked sugarcane and was targeted with Larra polita from the Philippines in 1925, apparently successfully.[38]

The next detection was in Georgia, USA, and at that time was assumed to be N. didactylus from the West Indies.[2] It was, in fact, three South American Neoscapteriscus species, N. abbreviatus, N . vicinus, and N. borellii, probably having arrived in ship ballast. They caused major problems for decades as they spread in the Southeastern USA.[39]Scapteriscus mole cricket populations had built up since the early decades of the 20th century and damaged pastures, lawns, playing fields, and vegetable crops. From the late 1940s, chordane had been the insecticide of choice to control them, but when chordane was banned by the U.S. EPA in the 1970s, ranchers were left with no economic and effective control method. Especially to aid Florida ranchers, a project that became known as the UF/IFAS Mole Cricket Research Program was initiated in 1978. In 1985, a multiple-authored report was published on accomplishments.[40] In 1988, an account was published on prospects for biological control,[41] and in 1996 an account of promising results with biological control.[42] The program ended in 2004 after 25 years of running monitoring stations, and in 2006 a summary publication announced success: a 95% reduction in mole cricket numbers in northern Florida, with biological control agents spreading potentially to all parts of Florida.[43] Efforts to use Larra bicolor as a biological control agent in Florida began by importing a stock from Puerto Rico. It became established in a small area of southeastern Florida, but had little effect on Neoscapteriscus populations.[44] A stock from Bolivia became established in northern Florida and spread widely (with some help) to most of the rest of the state and neighboring states.[45] Its survival depends upon the availability of suitable nectar sources.[46][47]

Once gravid female Ormia depleta flies were found to be attracted to the song of Neoscapteriscus males in South America,[48] a path to trap these flies with synthetic mole cricket songs was opened. Experimentation then led to a rearing method.[49] Laborious rearing of over 10,000 flies on mole cricket hosts allowed releases of living fly pupae at many sites in Florida from the far northwest to the far south, mainly on golf courses, and mainly in 1989-1991. Populations were established, began to spread, and were monitored by use of synthetic mole cricket song. Eventually, the flies were found to have a continuous population from about 29°N then south to Miami, but the flies failed to survive the winter north of about 29°N. Shipment and release of the flies to states north of Florida was thus a wasted effort. As the flies had been imported from 23°S in Brazil and could not overwinter north of 29°N, whether flies from 30°S in Brazil might survive better in northern Florida was investigated in 1999, but they did not.

The third biological control agent to target Neoscapteriscus in Florida was the South American nematode Steinernema scapterisci.[22] Small-scale releases proved it could persist for years in mole cricket-infested sandy Florida soils. Its use as a biopesticide against Neoscapteriscus was patented, making it attractive to industry. Industrial-scale production on artificial diet allowed large-scale trial applications in pastures[50] and on golf courses,[51] which succeeded in establishing populations in several counties, and these populations spread, but sales were disappointing, and the product was withdrawn from the market in 2014. Although experimental application was made in states north of Florida, only in southern Georgia was establishment of the nematode verified, suggesting little interest in the other states.

As pests

The main damage done by mole crickets is as a result of their burrowing activities. As they tunnel through the top few centimetres of soil, they push the ground up in little ridges, increasing evaporation of surface moisture, disturbing germinating seeds, and damaging the delicate young roots of seedlings.[2] They are also injurious to turf and pasture grasses as they feed on their roots, leaving the plants prone to drying out and damage by use.[3]

In their native lands, mole crickets have natural enemies that keep them under control.[52] This is not the case when they have been accidentally introduced to other parts of the world. In Florida from the 1940s through the 1980s, they were considered pests and were described as "a serious problem". Their population densities have since declined greatly. A University of Florida entomology report suggests that South American Neoscapteriscus mole crickets may have entered the United States at Brunswick, Georgia, in ship's ballast from southern South America around 1899, but were at that time mistakenly believed to be from the West Indies.[39] One possible remedy was biological pest control using the parasitoidal wasps Larra bicolor.[53] Another remedy that has been successfully applied is use of the parasitic nematode Steinernema scapterisci. When this is applied in strips across grassland, it spreads throughout the pasture (and potentially beyond) within a few months and not only controls the mole crickets, but also remains infective in the soil for future years.[38]

In human culture

Folklore

In Zambia, Gryllotalpa africana is held to bring good fortune to anyone who sees it.[54] In Latin America, Scapteriscus and Neocurtilla mole crickets are said to predict rain when they dig into the ground.[55] In Japan in the past, they seem to have been associated with the worms/corpses/bugs that announce a person's sins to heaven in the Koshin/Koushin belief.

As food

Gryllotalpa mole crickets have sometimes been used as food in West Java and Vietnam.[56] In Thailand, mole crickets (Thai: กระชอน) are valued as food in Isan. They are usually eaten fried along with sticky rice.[57]

In the Philippines, they are served as a delicacy called camaro in the province of Pampanga[58][59] and are a tourist attraction.[60][61] They are also served in parts of Northern Luzon.[56]

References

- Capinera, John L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 3983–3984. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- Thomas, William Andrew (1928). The Porto Rican mole cricket. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. p. 1.

- Potter, Daniel A. (1998). Destructive Turfgrass Insects: Biology, Diagnosis, and Control. John Wiley & Sons. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-57504-023-3.

- Cadena-Castañeda, Oscar J. (2015). "The phylogeny of mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpoidea: Gryllotalpidae)". Zootaxa. 3985 (4): 451–90. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3985.4.1. PMID 26250160.

- "Origin of Gryllotalpa". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- Orthoptera Species File

- Wang, H.; Lei, X.; Zhang, G.; Xu, C.; Fang, Y; Zhang, H. (2020). "The earliest Gryllotalpinae (Insecta, Orthoptera, Gryllotalpidae) from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber". Cretaceous Research. 107: Article 104292. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104292.

- Xu, C.; Fang, Y.; Wang, H. (2020). "A new mole cricket (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber". Cretaceous Research. 112: Article 104428. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104428.

- Martins-Neto, R.G. (1995). "Complementos ao estudo sobre os Ensifera (Insecta, Orthopteroida) da Formacao Santana, Cretaceo Inferior do Nordeste do Brasil". Revista Brasileira de Entomologia. 39: 321–345.

- Perrichot, V.; Néraudeau, Didier; Azar, Dany; Menier, Jean-Jacques; Nel, André (2002). "A new genus and species of fossil mole cricket in the Lower Cretaceous amber of Charente-Maritime, SW France (Insecta: Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae)". Cretaceous Research. 23 (3): 307–314. doi:10.1006/cres.2002.1011.

- Ratcliffe, B.C.; Fagerstrom, J.A. (1980). "Invertebrate lebensspuren of Holocene floodplains: their morphology, origin and paleoecological significance". Journal of Paleontology. 54: 614–630.

- "Family Gryllotalpidae". University of Florida. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Walker, Thomas J. "Family Gryllotalpidae". University of Florida Department of Entomology. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- Bennet-Clark, H. C. (1970). "The Mechanism and Efficiency of Sound Production in Mole Crickets". Journal of Experimental Biology. 52: 619–652.

- Lydekker, Richard (1879). Royal Natural History, Volume 6. Frederick Warne.

- Dawkins, Richard (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-198-57519-1.

- Forrest, T.G. (1983). Gwynne, D.T.; Morris, G.K. (eds.). Calling songs and mate choice in mole crickets (PDF). Orthopteran mating systems: sexual competition in a diverse group of insects. Westview. pp. 185–204.

- Dillman, A. R.; Cronin, C. J.; Tang, J.; Gray, D. A.; Sternberg, P. W. (2014). "A modified mole cricket lure and description of Scapteriscus borellii (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) range expansion and calling song in California". Environmental Entomology. 43 (1): 146–156. doi:10.1603/EN13152. PMC 4289669. PMID 24472207.

- Matheny, E.L. (1981). "Contrasting feeding habits of pest mole cricket species". Journal of Economic Entomology. 74 (4): 444–445. doi:10.1093/jee/74.4.444.

- Kattes, David H. (2009). Insects of Texas: A Practical Guide. Texas A&M University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-60344-082-0.

- Hudson, W. G.; Frank, J. H. Castner (1988). "Biological control of Scapteriscus spp. mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) in Florida". Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America. 34 (4): 192–198. doi:10.1093/besa/34.4.192.

- Nguyen, K. B.; Smart, G. C. (1992a). "Life cycle of Steinernema scapterisci n. sp. (Rhabditida)". Journal of Nematology. 24: 260–269.

- Nguyen, K. B., Smart, G. C. (1992b) Steinernema neocurtillis n. sp. (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae). Journal of Nematology 24: 463-467.http://journals.fcla.edu/jon/article/view/66425/64093

- "Mole cricket tutorial". University of Florida. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- Frank, J. H.; Erwin, T. L.; Hemenway, R. C. (2009). "Economically beneficial ground beetles. The specialized predators Pheropsophus aequinoctialis (L.) and Stenaptinus jessoensis (Morawitz): Their laboratory behavior and descriptions of immature stages (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Brachininae)". ZooKeys (14): 1–36. doi:10.3897/zookeys.14.188.

- Malysh, Yu.M.; Frolov, A.N. "Gryllotalpa africana Palis. - African Mole Cricket". AgroAtlas. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- Pendland, J.C., Boucias, D.G. 2008. Beauveria, pp. 401-404. In Capinera, J. L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer Science and Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1

- Houston, Terry (25 February 2011). "Mole Crickets". Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Callaghan, Jennifer (16 September 2013). "Native/Non-Native Animal of the Month - Mole Cricket". Urban Ecology Center. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Frank, J.H.; McCoy, E.D. (2014). "Zoogeography of mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) in the West Indies". Insecta Mundi. 0331 (328–0333): 1–14.

- "Pest mole crickets and their control". IFAS Entomology and Nematology Department. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- "Grasshoppers and Crickets (Order: Orthoptera)". Amateur Entomologists' Society. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "Mole Crickets". Guernsey Biological Records Centre. 29 April 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- Wolcott, G. N. (1941). "Establishment in Puerto Rico of Larra americana Saussure". Journal of Economic Entomology. 34: 53–56. doi:10.1093/jee/34.1.53.

- Vicente, N.E.; Frank, J.H.; Leppla, N.C. (2007). "Use of a beneficial nematode against pest mole crickets in Puerto Rico" (PDF). Proceedings of the Caribbean Food Crops Society. 42 (2): 180–186.

- Rentz, D.C.F. (1995). "The changa mole cricket, Scapteriscus didactylus (Latreille), a New World pest established in Australia (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae)". Australian Journal of Entomology. 34 (4): 303–306. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1995.tb01344.x.

- Frank, J.H., Leppla, N.C. 2008. Mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) and their biological control, pp. 2442-2449. In Capinera, J. L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer Science and Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1

- Walker, T. J.; Nickle, D. J. (1981). "Introduction and Spread of Pest Mole Crickets: Scapteriscus vicinus and S. acletus Reexamined" (PDF). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 74 (2): 158–163. doi:10.1093/aesa/74.2.158.

- Walker, T. J. (ed.) Mole crickets in Florida.| http://entnemdept.ifas.ufl.edu/walker/agbull846.html

- Hudson, W. G.; Frank, J. H.; Castner, J. L. (1988). "Biological control of Scapteriscus spp. mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) in Florida". Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America. 34 (4): 192–198. doi:10.1093/besa/34.4.192.

- Parkman, J.P.; Frank, J.H.; Walker, T.J.; Schuster, D.J. (1996). "Classical biological control of Scapteriscus spp. (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) in Florida". Environmental Entomology. 25 (6): 1415–1420. doi:10.1093/ee/25.6.1415.

- Frank, J.H.; Walker, T.J. (2006). "Permanent control of pest mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae: Scapteriscus) in Florida" (PDF). American Entomologist. 52: 138-144.

- Castner, J. L. (1988) Biology of the mole cricket parasitoid Larra bicolor (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) pp. 423-432, In Gupta, V. K. (ed.) Advances in Parasitic Hymenoptera Research. Brill; Leiden, 546 pp.

- Frank, JH; Leppla, NC; Sprenkel, RK; Blount, AC; Mizell, RF III (2009). "0063. Larra bicolor Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae): Its distribution throughout Florida". Insecta Mundi. 0063 (62–0067): 1–5.

- Portman, S. L.; Frank, J. H; McSorley, R.; Leppla, N. C. (2009). "Fecundity of Larra bicolor (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae) and its implications in parasitoid: host interaction with mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae: Scapteriscus)". Florida Entomologist. 92: 58–63. doi:10.1653/024.092.0110.

- Portman, S. L.; Frank, J. H.; McSorley, R.; Leppla, N. C. (2010). "Nectar-seeking and host-seeking by Larra bicolor (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae), a parasitoid of Scapteriscus mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae)" (PDF). Environmental Entomology. 39 (3): 939–943. doi:10.1603/en09268. PMID 20550809. S2CID 19940455.

- Fowler, H. G.; Kochalka, J. N. (1985). "New record of Euphasiopteryx depleta(Diptera: Tachinidae) from Paraguay: attraction to broadcast calls of Scapteriscus acletus (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae". Florida Entomologist. 68 (1): 225–226. doi:10.2307/3494349. JSTOR 3494349.

- Wineriter, S. A.; Walker, T. J. (1990). "Rearing phonotactic parasitoid flies (Diptera: Tachinidae, Ormiini, Ormia spp.)". Entomophaga. 35 (4): 621–632. doi:10.1007/bf02375096. S2CID 27347119.

- Parkman, J. P.; Frank, J. H.; Nguyen, K. B.; Smart, G. C. (1993). "Dispersal of Steinernema scapterisci (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) after inoculative applications for mole cricket control in pastures". Biological Control. 3 (3): 226–232. doi:10.1006/bcon.1993.1032.

- Parkman, J. P.; Frank, J. H.; Nguyen, K. B.; Smart, G. C. (1994). "Inoculative release of Steinernema scapterisci (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) to suppress pest mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae) on golf courses". Environmental Entomology. 23 (5): 1331–1337. doi:10.1093/ee/23.5.1331.

- Frank, J.H.; Walker, T.J. (2006). "Permanent control of pest mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae: Scapteriscus) in Florida" (PDF). American Entomologist. 52: 138-144.

- "Mole Crickets Get Rid of These Invasive Pests". University of Florida. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Mbata 1999

- Fowler 1994

- De Foliart, Gene R. (1975–2002). "The Human Use of Insects as a Food Resource: A Bibliographic Account in Progress". Archived from the original on 2003-03-11. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Thai Insect Recipe: Dry Fried Crickets คั่วแมลงกระชอน

- "'Biyahe ni Drew' Food Trip: 11 Must-Try Restaurants in Pampanga". GMA News Online. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Manabat, Manabat (14 Aug 2014). "Cabalen: 28 years of serving Kapampangan cuisine". Punto Central Luzon. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "Pampanga Culinary Special". Department of Tourism (Philippines). Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Dy-Zulueta, Dolly (5 October 2014). "Weekend Chef - Sisig galore at Big Bite! food fest in Pampanga, Oct. 17 to 19". InterAksyon.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gryllotalpidae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Gryllotalpidae. |

- Mole Cricket at Australian Museum

- Houston, Terry (2011) Information sheet: Mole Crickets at Western Australian Museum

- Prendergast, Amy (2012) "Solving the Mystery of the Hidden Callers of the Night" at Australian Wildlife Secrets

- Mole Cricket Knowledge Base at University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

- On the University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Featured Creatures website

- Bug-a-Boo’s or Grubs Up