Richard Kuklinski

Richard Leonard Kuklinski (/kʊˈklɪnski/; April 11, 1935 – March 5, 2006) was an American serial criminal and murderer. Kuklinski was engaged in criminal activities for most of his adult life. He ran a burglary ring and distributed pirated pornography. Kuklinski killed several people he lured with offers of a business deal so that he could rob them of their cash.[2] Law enforcement officials described him as someone who killed for profit.[3] Kuklinski lived with his wife and children in the New Jersey suburb of Dumont. They knew him as a loving father and husband who provided for his family, but one who also had a violent temper and was physically abusive to his wife. His family stated that they were unaware of his crimes. He was given the moniker Iceman by authorities after they discovered that he had frozen the body of one of his victims in an attempt to disguise the time of death.[1][4]

Richard Kuklinski | |

|---|---|

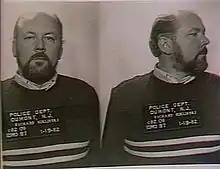

Kuklinski's 1982 mugshot | |

| Born | Richard Leonard Kuklinski April 11, 1935 Jersey City, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | March 5, 2006 (aged 70) Trenton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | The Iceman Big Rich[1] |

| Occupation | Hitman, film distributor |

| Spouse(s) | Linda (divorced); Barbara Kuklinski (m. 1961; divorced) |

| Children | 2 sons from first marriage; 2 daughters & 1 son from second marriage |

| Conviction(s) | 5 murders |

| Criminal charge | Murder (5 counts) |

| Penalty | 2 consecutive life sentences |

Eventually, Kuklinski came to the attention of law enforcement when an investigation into his burglary gang linked him to several murders. An eighteen-month long undercover operation led to his arrest in December 1986.[5] In 1988, he was sentenced to life imprisonment after being convicted of killing two members of his burglary gang and two other associates. In 2003, he received an additional 30-year sentence after confessing to the murder of a mob-connected police officer.[6]

After his murder convictions, Kuklinski gave interviews to writers, prosecutors, criminologists and psychiatrists. He claimed to have murdered anywhere from 100 to 200 men, often in gruesome fashion.[5] Most of these additional murders have not been corroborated.[7] He also alleged that he worked as a hitman for the Mafia,[5] and that he was a participant in several famous Mafia killings, including the murders of mob bosses Paul Castellano and Carmine Galante, mob soldier Roy Demeo, and Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa. These claims are considered dubious by law enforcement and mob experts.[8][7][5] He was the subject of three HBO documentaries aired in 1992, 2001 and 2003;[5] several biographies, and a 2012 feature film starring Michael Shannon and Winona Ryder.[9]

Personal life

Early life

Richard Kuklinski was born in his family's apartment on 4th Street in Jersey City, New Jersey, to Stanisław "Stanley" Kukliński (1906–1977), a Polish immigrant from Karwacz, Masovian Voivodeship[10] who worked as a brakeman on the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, and Anna McNally (1911–1972) from Harsimus,[11] a daughter of Catholic Irish immigrants from Dublin, who worked in a meat-packing plant during Richard's childhood.[12] He was the second of four children.

According to Richard Kuklinski, Stanley Kuklinski was a violent alcoholic who beat his children regularly and sometimes beat his wife.[6] Stanley abandoned the family while Richard was still a child, but returned periodically, usually drunk, and his returns were often followed by more beatings for Richard.[13] Anna was also often abusive. She would beat Richard with broom handles (sometimes breaking the handle on his body during the assaults) and other household objects. He recalled an incident during his pre-teen years when his mother attempted to kill Stanley with a kitchen knife.[6] Anna was a zealous Catholic and believed that stern discipline should be accompanied by a strict religious upbringing, the same way she was raised. She raised her son in the Roman Catholic Church, where he became an altar boy.[12] Kuklinski later rejected Catholicism. Kuklinski regarded his mother as a "cancer" who destroyed everything she touched.[14]

Kuklinski had three siblings. His older brother Florian (1933–1941) died at the age of seven from injuries inflicted by his father during a violent beating.[15] The family lied to the police, saying that Florian had accidentally fallen down a flight of steps.[15] Stanley abandoned the family shortly after he murdered his first son. Kuklinski, who was the second son, had a younger sister, Roberta (1942–2010), and a younger brother, Joseph (1944–2003), who in 1970 was convicted of raping a 12-year-old girl and murdering her by throwing her off the top of a five-story building (along with her pet dog).[16][17] When asked about his brother's crimes, Kuklinski replied: "We come from the same father."[12]

Criminal life

Early crimes

In the mid-1960s, Kuklinski began working at a Manhattan film lab. Through the lab he had access to master copies of popular films, and he began making bootleg copies of Disney animated films which he could then sell. Kuklinski discovered there was a lucrative market for tapes of pornographic movies too; copying and distributing pornography became a regular source of income for him.[18] He was once arrested for passing a bad check, the only crime he was charged with prior to his arrest for murder. He was photographed and fingerprinted, but the charges were dropped when he agreed to pay back the money owed.[1] Several of his known murder victims were men he had met through trafficking pornography and drugs.[19] He also headed a group which specialized in carrying out burglaries. This group consisted of Gary Smith, Barbara Deppner, Daniel Deppner, Percy House, and Richard Kuklinski himself.[20][1]

Murder of George Malliband

On January 30, 1980, Kuklinski killed George Mallibrand. He had met Kuklinski who promised to sell him tapes.[3] Malliband was reportedly carrying $27,000 at the time.[19] Malliband's body was shot multiple times and was found in a 55-gallon drum.[3] Kuklinski would later accept a plea deal, where he admitted to shooting him five times and explained that "It was due to business".[21]

The drum was located near the Chemitex chemical plant in Jersey City. Kuklinski had cut the tendons of Malliband's leg in order to force it into the barrel.[22] This was the first murder to be directly linked to Kuklinski, as Malliband's brother told police that he had been on his way to meet Kuklinski the day he disappeared.[1]

Murder of Paul Hoffman

In 1982, Kuklinski met Paul Hoffman, a 51-year-old pharmacist who occasionally frequented "the store" in Paterson, New Jersey, a storefront with a large backroom where a wide variety of stolen items could be bought and sold. Hoffman hoped to make a big profit by purchasing, at a low cost, large quantities of stolen Tagamet, a popular drug used to treat peptic ulcers, which he could then resell through his pharmacy. He believed that Kuklinski could supply the drug and badgered him to make a deal.[23] Hoffman was last seen on his way to meet Kuklinski with $22,000 to buy prescription drugs from Kuklinski.[3][19] Kuklinski would later accept a plea deal where he admitted to killing Hoffman on April 29, 1982.[2]

Murder of Gary Smith

By the early 1980s, Kuklinski's burglary gang was coming under more scrutiny from law enforcement. In December 1982, Percy House, a member of the gang, was arrested. House would later agree to testify against Kuklinski and was placed in protective custody.[24] Warrants were also issued for the arrest of two more gang members, Gary Smith and Daniel Deppner. Kuklinski urged them to lie low and rented them a room at the York Motel in North Bergen, New Jersey. Kuklinski was angered when he learned that Smith had left the motel to visit his daughter and also feared that Smith, who had recently spoken of giving up crime and going straight, might become an informant against him.[25]

According to the testimony of Barbara Deppner, Kuklinski, Daniel Deppner and House (who was still in jail at the time) decided that Smith had to be killed. Kuklinski therefore fed Smith a hamburger laced with poison followed by Daniel Deppner strangling Smith with a lamp cord.[20] According to forensic pathologist Michael Baden, Smith's death would probably have been attributed to something non-homicidal in nature (like drug overdose for instance) had Kuklinski relied solely on the cyanide. However, the ligature mark around Smith's neck proved to investigators that he was murdered.[6]

When Deppner's ex-wife, Barbara, failed to return with a car to remove the body, they placed it in between the mattress and box spring. Over the next four days, a number of patrons rented the room, and although they thought the smell in the room was odd, most of them did not think to look under the bed.[6][26] Finally, on December 27, 1982, after more complaints from guests about the smell, the motel manager investigated and found Smith's decomposing body.

Murder of Daniel Deppner

After Smith's murder, Kuklinski moved Deppner to an apartment in Bergenfield, New Jersey, belonging to Rich Patterson, then-fiancé of Kuklinski's daughter Merrick. Patterson was away at the time, but Kuklinski had access to the apartment.[27] At some point between February and May 1983, Deppner was killed by Kuklinski.[27] Investigators later deduced that he was murdered in Patterson's apartment after finding a bloodstain on the carpet.[28] Kuklinski enlisted Patterson's help to dispose of Deppner's body, telling Patterson that the victim was a friend who had been in trouble with the law, and that someone must have broken in and killed him over the weekend. He added that it was best to dump the body to avoid trouble with the police. Afterwards Kuklinski urged Patterson to just forget about the incident.[28] Kuklinski made another mistake when he told an associate that he had killed Deppner.[29]

Deppner's body was found on May 14, 1983, when a cyclist riding down Clinton Road in a wooded area of West Milford, New Jersey, spotted the corpse being eaten by a turkey vulture. Kuklinski had wrapped the body inside green garbage bags before dumping it.[1] Medical examiners listed Deppner's cause of death as "undetermined", although they noted pinkish spots on his skin, a possible sign of cyanide poisoning. Deppner had also been strangled. Law enforcement theorized that Deppner must have already been incapacitated, such as by poison, as he had no defensive wounds and healthy adult men are rarely killed by strangulation.[28] The medical examiner found that Deppner's stomach was full of undigested food, meaning he had died shortly after (or during) a meal. The beans that Deppner had eaten were burned, so they reasoned that it must have been a home-cooked meal, as a restaurant would probably not get away with serving burned food to a customer.[27] Investigators noted that the body had been discovered just three miles (5 kilometers) from a ranch where Kuklinski's family often went horseback riding. Deppner was the third associate of Kuklinski's to have been found dead.

Louis Masgay discovered

On September 25, 1983, the body of Louis Masgay was found near a town park off Clausland Mountain Road in Orangetown, New York, with a bullet hole in the back of his head. Masgay had disappeared over two years earlier, on July 1, 1981, the day he was due to meet Kuklinski at a New Jersey diner to purchase a large quantity of blank videocassette recorder tapes, for which Masgay had hidden $95,000 in his van.[3] His body was stored in a freezer and was found 15 months later.[3] Kuklinski would later say he shot Masgay in the back of the head after accepting a plea deal with prosecutors.[21]

However, Kuklinski did not allow the body to thaw completely before he dumped it and he also wrapped it in plastic garbage bags, which kept it insulated and partially frozen. The Rockland County medical examiner found ice crystals inside the body on a warm September day. Had the body thawed completely before discovery, the medical examiner stated that he probably would have never noticed Kuklinski's trickery.[30] Detectives also realised that Masgay was wearing the same clothes his wife and son had said he was wearing the day he disappeared.[30] The discovery that Kuklinski had frozen Masgay's body is what led authorities to nickname him "Iceman".[1] Newspapers reporting on the subsequent trial frequently used Kuklinski's moniker of "Iceman" in headlines about the trial.[1]

Investigation and arrest

Kuklinski first came to the attention of Pat Kane, a detective in the New Jersey State Police when, with help from an informant, Kane connected him to a gang who were carrying out burglaries in northern New Jersey and began building a file on him.[1] Eventually, five unsolved homicides, namely the deaths of Hoffman, Smith, Deppner, Masgay and Malliband, were linked to Kuklinski because he had been the last known person to see each of them alive.[6] A joint task force titled "Operation Iceman" was created between the New Jersey Attorney General's office and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms which was dedicated to arresting and convicting Kuklinski.[31][3][32] The ATF were involved due to Kuklinski's selling firearms.[1]

ATF Special Agent Dominick Polifrone went undercover for 18 months to apprehend Kuklinski.[31] Starting in 1985, Kane and Polifrone worked with Phil Solimene, a close long-time friend of Kuklinski, to get Polifrone close to Kuklinski. Posing as a Mafia-connected criminal named Dominic Provenzano, Polifrone initially purchased a silenced handgun from Kuklinski.[33] In recordings, Kuklinski discussed having killed a man by putting poison in his hamburger, and of a man whose dead body was kept in a freezer for two and a half years to confuse the time of death. Kuklinski discussed how he preferred poison saying "Why be messy? You do it nice and calm."[34] He asked Polifrone if he could supply him with pure cyanide. Polifrone told Kuklinski he wanted to hire him to carry out a hit against a wealthy Jewish associate in a cocaine deal robbery, and recorded Kuklinski speaking in detail about how he would do it.[35] Kuklinski was also recorded boasting that he had once killed a man by putting cyanide on his hamburger, and of his plans to kill "a couple of rats" (Barbara Deppner and Percy House).[24]

On December 17, 1986, it was arranged for Kuklinski to meet Polifrone to get cyanide for a planned murder, which was to be an attempt on a police detective working undercover. After being recorded by Polifrone, Kuklinski went for a walk by himself. He tested Polifrone's (purported) cyanide on a stray dog, using a hamburger as bait, and saw it was not poison. Suspicious, Kuklinski decided not to go through with the planned murder and went home instead.[36] He was arrested at a roadblock two hours later. His wife was charged with disorderly conduct in trying to prevent his arrest.[3] A gun was found in the car, and she was charged with possession of an illegal firearm, as she had been in the car where it was found.[24]

Trial

Prosecutors charged Kuklinski with five murder counts and six weapons violations, as well as attempted murder, robbery, and attempted robbery. Officials said Kuklinski had large sums of money in Swiss bank accounts and a reservation on a flight to that country.[3][32] Kuklinski was held on a $2 million bail bond and made to surrender his passport.[32][37] After arrest, Kuklinski told reporters ″This is unwarranted, unnecessary. These guys watch too many movies.″ At a press conference, New Jersey state Attorney General W. Cary Edwards characterized the motive for the murders as "profit", and said ″He set individuals up for business deals, they would disappear and the money would end up in his hands.″. [3]

At trial, a number of Kuklinski's former associates including Percy House and Barbara Deppner gave evidence against him as did agent Polifrone. The case was prosecuted by Deputy Attorney General Robert Carrol while Kuklinski was represented at trial by a public defender. Kuklinksi's lawyer argued that Kuklinski had no history of violence who only projected a tough image, including his statements to agent Polifrone. The defense theory was that Deppner was responsible for the murder of Smith and that there had been no cause of death determined for Deppner. Additionally, he argued that the testimony of House and Barbara Deppner was unreliable because they had both lied to the police in the past, and House had been granted immunity from prosecution.[38] In March 1988, a jury found Kuklinski guilty of murdering Smith and Deppner, but found that the deaths were not proven to be by Kuklinski's own conduct, meaning he would not face the death penalty.[39] He was then sentenced to a minimum 60 years in prison.[2][21]

After the trial, Kuklinski then plead guilty to killing Masgay and Mallibrand. Kuklinski was then sentenced to an additional two life sentences to be served consecutively. State prosecutors explained that he would then spend the rest of his life in prison even if he were to have successful appeals to his previous convictions. Kuklinski also confessed to having killed Hoffman, but prosecutors decided to not pursue sentencing citing that more time would not have any impact on Kuklinski's prison sentence.[2][21] As part of the deal, the gun charge against his wife and an unrelated marijuana possession charge against his son were also dropped.[40][21] Kuklinski was to be ineligible for parole until he was 111 years old.[5][21] He was incarcerated at Trenton State Prison.[41]

Statements made during interviews

During his incarceration, Kuklinski granted interviews to prosecutors, psychiatrists, criminologists, and writers. Several television producers also spoke to Kuklinski about his criminal career, upbringing, and personal life. These talks culminated in three televised documentaries known as The Iceman Tapes, which were aired on HBO in 1992, 2001, and 2003. According to his daughter Merrick Kuklinski, it was her mother who convinced Richard to do the interviews and she was paid "handsomely" for them.[42] In the last installment, The Iceman and the Psychiatrist, Kuklinski was interviewed by renowned forensic psychiatrist Dr. Park Dietz in 2002. Dietz stated he believed Kuklinski suffered from antisocial personality disorder and paranoid personality disorder.

Writers Anthony Bruno and Philip Carlo wrote biographies of Kuklinski.[9] Kuklinski's wife received a share of the profits from the Bruno book.[4]

In interviews, Kuklinski claimed to have been a mafia hitman and to have killed 100 or 200 people.[5][43] He alleges he used multiple ways to kill people, including a crossbow, icepicks, a bomb attached to remote controlled toy, firearms, grenades, as well as cyanide solution spray which he considered to be his favorite.[5] He says he committed his first murder at 14, and would later use homeless people to murder for practice.[44] In 2006, Paul Smith, a member of the task force which arrested Kuklinski and later a supervisor of the organized crime division of the New Jersey Attorney General's office, said "I checked every one of the murders that Kuklinski said he committed, and not one was true.". He added “Authorities throughout the country could not corroborate one case based on the tidbits that Kuklinski gave.”[7] In 2020, Dominick Polifrone said "I don’t believe he killed 200 people. I don’t believe he killed 100 people. I’ll go as high as 15, maybe."[31]

Kuklinski's claims that he dumped bodies in caves in Bucks County, Pennsylvania and fed a victim to flesh-eating rats in the caves. However, in 2013 the Philadelphia Inquirer noted that the caves have had a lot of visitors since Kuklinski's time, and no human remains have been found. Local cave enthusiast Richard Kranzel also queried the idea of flesh-eating rats, saying "The only rats I have encountered in caves are 'cave rats,' and they are reclusive and shy creatures, and definitely not fierce as Kuklinski claims."[43] Authorities also doubt that he stored a body for two years in a Mister Softee truck.[5]

Robert Prongay

In interviews and documentaries, Kuklinski says he killed Robert Prongay, whom he says had been a mentor to him.[45] Prongay was murdered in 1984 and he had been shot multiple times in the head and found in his Mister Softee ice cream truck. Robbery had not been considered a motive at the time. He was set to go on trial for blowing up the front door of his ex-wife's house.[46] Kuklinski says that Prongay taught him how to use cyanide and other methods to kill, and that Prongay told him to freeze the body of Masgay. However, Kuklinski says he had killed Prongay after he had threatened his family. Investigators considered Kuklinski a prime suspect since 1986, but the director of the New Jersey Division of Criminal Justice said that no charges were sought because Kuklinski was convicted of other crimes.[4] In 1993, in response to his claims, Hudson County Prosecutor said that new charges against Kuklinski were possible since the Prongay murder was still an open investigation and that they would assess whether there was enough to prosecute.[45] Ultimately no charges were pressed against him for the Prongay murder.

Roy DeMeo

Kuklinski claimed to have killed Gabino Crime family member Roy DeMeo in an interview for the 1993 book "The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer" by Anthony Bruno.[45] He described DeMeo as a mentor of his, whom he had met after he fell behind on a loan he had taken out to distribute pornography. He received a beating and later became business partners. Kuklinski says DeMeo taught him how murder for hire could be a way to make money.[4] However, author Jerry Capeci who has written extensively about DeMeo and the mafia, doubts that Kuklinski killed DeMeo.[5] Most sources indicate that DeMeo was killed by members of his own crew, with no suggestion that Kuklinski was involved.[47][48][49] Kuklinski is not mentioned in Capeci and Gene Mustain's book about the DeMeo crew, Murder Machine or Albert DeMeo's account of his father's life in the mob, For the Sins of My Father.[50][49]

Murder of Peter Calabro

In his 2001 HBO interview, Kuklinski confessed to killing Peter Calabro, an NYPD detective who had been ambushed and shot dead by an unknown gunman on March 14, 1980. Calabro was rumored to have mob connections and had been investigated for selling confidential information to the Gambino family.[41] His wife Carmella had drowned in mysterious circumstances three years earlier and members of her family believed that Calabro himself was responsible for her death. At the time, his murder was thought by law enforcement to have been a revenge killing either carried out or arranged by his deceased wife's relatives.[51] Her brothers were regarded as "key suspects" but the crime remained unsolved.[52]

The Bergen County prosecutor believed Kuklinski's confession to be a fabrication, but his successor decided to proceed with the case.[53] In February 2003 Kuklinski was formally charged with Calabro's murder and received another sentence of 30 years. This was considered moot, as he was already serving multiple life sentences and ineligible for parole until he was over the age of 100.[5] Describing the murder, Kuklinski said that he parked his van on the side of a narrow road, forcing other drivers to slow down to pass. He lay in a snowbank behind his van until Calabro came by at 2 a.m., then stepped out and shot him in the head with a sawed-off shotgun, decapitating Calabro. He stated that he was unaware that Calabro was a police officer at the time, but said he probably would have murdered him anyway had he known.[41]

Kuklinski claimed he had been paid to kill Calabro by Gambino crime family soldier (later underboss) Sammy "The Bull" Gravano and that Gravano had provided him with the murder weapon. Gravano, who was then serving a 20-year sentence in Arizona for drug trafficking, was also indicted for the murder and Kuklinski was set to testify against him.[54][53] Gravano denied any involvement in Calabro's death and rejected a plea deal, under which he would have received no additional jail time if he confessed to the crime and implicated all his accomplices.[55][56] The charges against Gravano were dropped after Kuklinski's death in 2006.[57]

Other killings

Kuklinski also alleged that he was a Mafia contract killer who worked for all of the Five Families of New York City, as well as the DeCavalcante family of New Jersey.[58] He claimed to have carried out dozens of murders on behalf of Gambino soldier Roy DeMeo. He said that he was one of the hitmen who assassinated Bonanno family boss Carmine Galante in July 1979,[44] and Gambino family boss Paul Castellano in December 1985.[59] For the latter hit, Kuklinski said he was personally recruited by John Gotti ally Sammy Gravano, who instructed him to kill Castellano's driver and bodyguard, Thomas Bilotti.[60] He told Philip Carlo he was hired by John Gotti to kidnap, torture and murder John Favara, the man who accidentally killed Gotti's 12-year-old son Frank after hitting him with his car.[44]

When he became a Government witness in 1990, Sammy Gravano admitted to planning the murder of Castellano and Bilotti, but said the shooters were all members of John Gotti's crew and were chosen by Gotti; he did not mention Kuklinski.[61][62] Anthony Bruno felt that Kuklinski's participation in the killing of Castellano was “highly unlikely”.[63] Bruno noted that in 1986 Anthony Indelicato was convicted of Galante's murder and Kuklinski was not mentioned during the trial.[64] Philip Carlo later wrote that Kuklinski's claim to have participated in Galante's murder was untrue.[65]

Jimmy Hoffa

In his 2001 HBO interview, Secrets of a Mafia Hitman, Kuklinski said he knew who killed former Teamsters union president Jimmy Hoffa. He did not name the culprit, but said it was not himself.[12] However, he later claimed that he actually killed Hoffa. In his account, Kuklinski was part of a four-man hit team who picked up Hoffa in Detroit. While they were in the car, Kuklinski killed Hoffa by stabbing him with a large hunting knife. He said he then drove Hoffa's body from Detroit to a New Jersey junkyard, where it was placed in a drum and set on fire, then buried in the junkyard. Later, fearing an accomplice might become an informant, the drum was dug up, placed in the trunk of a car, and compacted to a cube. It was sold, along with hundreds of other compacted cars, as scrap metal. It was shipped off to Japan to be used in making new cars.[8][44]

Deputy Chief Bob Buccino, who worked on the Kuklinski case, said "They took a body from Detroit, where they have one of the biggest lakes in the world, and drove it all the way back to New Jersey? Come on." Buccino added: "We didn't believe a lot of things he said."[66] Former FBI agent Robert Garrity called Kuklinski's admission to killing Hoffa “a hoax” and said Kuklinski was never a suspect in Hoffa's disappearance, adding "I've never heard of him."[8] Bruno said he investigated Kuklinski's alleged involvement in Hoffa's disappearance, but concluded that “[his] story didn't check out”. He opined that Kuklinski made the confession in order to “add extra value to his brand”[63] and so he omitted the story from his biography of Kuklinski.[67]

Personal life

Kuklinski's first marriage was to a woman nine years his senior named Linda, with whom he had two sons (Richard Jr. and David). While Richard was working for a trucking company he met Barbara Pedrici, who was a secretary at the same firm. Kuklinski and Barbara married in 1961 and had two daughters, Merrick[42] and Christin, and a son, Dwayne.[68] Barbara described his behavior as alternating between "good Richie" and "bad Richie."[69] "Good Richie" was a hard-working provider and an affectionate father and loving husband, who enjoyed time with his family. Barbara remembered that when Merrick became seriously ill soon after she was born, Richard stayed up night after night to care for her.[70]

In contrast, "Bad Richie" – who would appear at irregular intervals: sometimes one day after another, other times not appearing for months – was prone to unpredictable fits of rage, smashing furniture and domestic violence. During these periods, he was physically abusive to his wife (one time breaking her nose and giving her a black eye) and emotionally abusive towards his children. Merrick later recalled that he once killed her dog right in front of her to punish her for coming home late.[42] Barbara claimed in an interview that once, during an argument in a car, she told Richard she wanted to see other people. He responded by silently jabbing her from behind with a hunting knife so sharp she did not even feel the blade go in. He told her that she belonged to him, and that if she tried to leave he would kill her entire family; when Barbara began screaming at him in anger, he throttled her into unconsciousness.[68] Merrick also remembered a number of road rage incidents involving her father.[42]

Kuklinski's family and Dumont, New Jersey neighbors were never aware of his activities, and instead believed he was a successful businessman. Barbara suspected that at least some of his income was from illegal activities, due to their lifestyle and the large amounts of cash he often possessed, but she never expressed these worries to him,[69] instead maintaining a "don't ask questions" philosophy when it came to his business life, choosing not to ask about his business partners or how he made his money. If Richard suddenly left the house in the middle of the night, Barbara would never ask where he was going.[70] The Kuklinskis divorced in 1993, when Richard was in prison. Barbara said the divorce was for "money reasons". She continued to visit him in prison, but only about once a year.[71]

Death and legacy

In October 2005, after nearly 18 years in prison, Kuklinski was diagnosed with Kawasaki disease (an inflammation of the blood vessels). He was transferred to a secure wing at St. Francis Medical Center in Trenton, New Jersey. Although he had asked doctors to make sure they revived him if he developed cardiopulmonary arrest (or risk of heart attack), his then-former wife Barbara had signed a "do not resuscitate" order. A week before his death, the hospital called Barbara to ask if she wished to rescind the instruction, but she declined.[68] Kuklinski died at age 70 on March 5, 2006.[5] At the request of Kuklinski's family, noted forensic pathologist Michael Baden reviewed his autopsy report. Baden confirmed that Kuklinski died of cardiac arrest and had been suffering with heart disease and phlebitis.[56]

Michael Shannon plays Kuklinski in the 2012 film The Iceman loosely based on Anthony Bruno's book The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer.[72] The film was directed by Ariel Vromen and also stars Winona Ryder, Ray Liotta, Stephen Dorff, and Chris Evans.[9]

References

- Camisa, Harry; Franklin, Jim (January 1, 2003). "RICH JOHN AND THE ICEMAN". Inside Out : Fifty Years Behind the Walls of New Jersey's Trenton State Prison. Windsor, N.J.: Windsor Press. pp. 247–249. ISBN 0-9726473-0-9. OCLC 52937928.

- "'Iceman' pleads guilty to 2 more killings, admits another". The Central New Jersey Home News. New Brunswick, New Jersey. May 26, 1988. p. 17.

- Dolan, Julia (December 18, 1986). "Man Charged With Killing Associates, Accomplices". Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021.

- "Ice Man: Tells of Killings". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. September 2, 1993. pp. D2.

- Douglas, Martin (March 9, 2006). "Richard Kuklinski, 70, a Killer of Many People and Many Ways, Dies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- "The Iceman Tapes: Conversations with a Killer". America Undercover. 1992. HBO.

- Markos, Kibret (June 27, 2006). "Ice Man Book Ridiculed as More Fiction than Fact". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. p. A1.

“I checked every one of the murders that Kuklinski said he committed,” said Smith, who was a member of the task force that ultimately arrested Kuklinski, “and not one was true." “Authorities throughout the country could not corroborate one case based on the tidbits that Kuklinski gave,” Smith said.

- "Former FBI agent says Hoffa claim is hoax". UPI. April 18, 2006. Archived from the original on October 25, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- "7 Film Action yang Berdasarkan Kisah Nyata". CNN Indonesia. November 7, 2020. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021.

- "Richard Kuklinski – zabijanie miał we krwi?" Archived February 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. More Maiorum 1/2016, pp. 28-37 (Polish only); retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Carlo 2006, pp. 14-15.

- The Iceman - Confessions of a Mafia Hitman (DVD). HBO. June 1, 2004.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 1". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 6". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Carlo 2006, p. 16.

- Carlo 2006, pp. 132-134.

- "Jersey City Man Arrested In Death of 12-Year-Old Girl". The New York Times. September 16, 1970. Archived from the original on August 30, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

... of a 12-year-old girl who apparently was thrown from the roof of a building. Joseph Kuklinski was taken into custody from his home at 434 Central Avenue

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 20". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- "JERSEY MAN CHARGED IN 5 MURDERS LINKED WITH FAKE BUSINESS DEALS". New York Times. December 18, 1986. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- August, Betsy (February 19, 1988). "'Iceman' witness details murder". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey.

- Sanderson, Bill (May 26, 1988). "'Iceman' Pleads Guilty - Gets two more life sentences for murders". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. pp. A-1, A-18.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 28". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 12". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 34". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 8". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Mikkelson, David (June 13, 1999). "The Body Under the Bed" Archived December 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Snopes.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 18". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 33". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 29". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 10". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Crystal, Ponti (May 26, 2020). "'The Iceman': An Undercover Agent Reflects on Taking Down Notorious Hitman Richard Kuklinski". A&E. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "Iceman: suspect in 5 deaths arrested". Montreal Gazette. Associated Press. December 18, 1986. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 14". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- "Killing suspect bragged about his technique". The Record. January 14, 1987. p. A-10.

- Carlo 2006, pp. 363-364.

- Carlo 2006, pp. 363-365.

- "Man charged with killing partners in crime". Washington Observer-Reporter. Associated Press. December 18, 1986. p. B-5. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- McMahon, Bob (February 18, 1988). "Kuklinski was set up, lawyer say". The Morning Call. Allentown, Pennsylvania.

- United Press International (March 16, 1988). "Jury convicts 'Iceman' killer". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. p. A-2.

- "Killer Admits More Murders". New York Times. May 26, 1988. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Jacobs, Andrew (February 21, 2003). "Reality TV Confession Leads to Real-Life Conviction". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

During the hearing, he said he did not know that his intended target was a police officer.

- Rayman, Graham (June 15, 2016). "Interviews with Queer Women: The Iceman's Daughter". Go Magazine. New York City: Modern Spin Media, LLC. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- "Human remains in a Bucks County cave?". Philadelphia Inquirer. June 17, 2013. Archived from the original on October 25, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- Harris, Paul (April 23, 2006). ""Did Iceman accept mob contract on union boss?"". The Guardian.

- Consoli, Jim (September 2, 1993). "Dumont's 'Iceman' claims 100 killings". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. p. A3, D3. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021.

- Lynn, Kathleen; Lundstorm, Meg (August 12, 1984). "Fire-bomb suspect found shot to death". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. p. A51. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021.

- Mustain, Gene; Capeci, Jerry (2012). Murder Machine. Ebury Press. pp. 348–351. ISBN 978-0091941123.

- Carlo, Philip (2008). Gaspipe: Confessions of a Mafia boss. Harper Collins. pp. 125-129. ISBN 978-0061429842.

- DeMeo, Albert (2003). For the Sins of My Father: A Mafia Killer, His Son and the Legacy of a Mob Life. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-1854109187.

- Mustain, Gene; Capeci, Jerry (2012). Murder Machine. Ebury Press. pp. 463–478. ISBN 978-0091941123.

- Mustain, Gene; Capeci, Jerry (2012). Murder Machine. Ebury Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0091941123.

- Bruno, Anthony (2018). "Chapter 15". Immortal Monster. DarkHorse Multimedia. ASIN B07GTD1KX5.

- "Gravano: Heading to Trial for Allegedly Ordering Cop Killed". The Record. January 9, 2006. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

Molinelli's predecessor, William Schmidt, was still in office when Kuklinski first appeared on television and confessed to Calabro's murder. Schmidt did not return repeated phone calls, but had said in an interview he believed Kuklinski was fabricating the story. Molinelli came into office in 2002, vowing to crack cold cases. Gravano was charged soon after.

- Jacobs, Andrew (February 25, 2003). "Hit Man Implicates Hit Man In '80 Slaying, Authorities Say". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021.

- "'Bull' Rejected Plea in Cop Killing". The Record. March 8, 2006.

- "Gravano: "Bull" Rejected 2003 Plea Deal in Case of Slain Cop". The Record. March 8, 2006.

- Hague, Jim (March 20, 2006). ""The 'Iceman' cometh - and goeth Gruesome hit man and former NB resident Kuklinski, featured in HBO special, dies in prison at 70"". Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021.

- Carlo 2006, p. 1.

- Carlo 2006, pp. 232-238.

- Carlo 2006, pp. 307-312.

- "Was Hoffa iced by 'Iceman'? Book published a month after former NB resident Kuklinski's death gives account". Hudson Reporter. April 22, 2006. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- Maas, Peter (1997). Underboss. HarperCollins. pp. 367–385. ISBN 0-7862-1253-5.

- The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-blooded Killer Archived December 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine By Anthony Bruno, pg xvii

- Bruno, Anthony (2018). "Chapter 9". Immortal Monster. DarkHorse Multimedia.

- Carlo, Philip (2012). The Butcher: Anatomy of a Mafia Psychopath. Mainstream Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1845965884.

- Troncone, Tom (April 23, 2006). "Self-styled 'Ice Man' was Jimmy Hoffa's killer -- or colossal liar". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Introduction". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Higgenbotham, Adam (June 7, 2013). "Married to the Iceman". The Telegraph. London, England. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- Bruno, Anthony (1993). The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. New York, New York: Delacorte. p. 50. ISBN 978-0345540119.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. "Chapter 3". The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- "Date me or I'll kill your mother Ex-wife of notorious 'Ice Man' talks about years with mob killer". Hudson Reporter. July 23, 2006. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- Zakarin, Jordan (March 26, 2012). "'Iceman' Poster Stars Michael Shannon as a Menacing Killer". The Hollywood Reporter. Los Angeles, California: Eldridge Industries. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

Further reading

- Carlo, Philip (2006). The Ice Man: Confessions of a Mafia Contract Killer. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-34928-8.

- Bruno, Anthony (2013) [1993]. The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer. ROBERT HALE LTD. ISBN 9780709052722.

- Bruno, Anthony (2018). Immortal Monster. DarkHorse Multimedia. ASIN B07GTD1KX5.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Richard Kuklinski |