Richard the Lionheart's encounters with lions

The question of whether or not Richard the Lionheart ever came into contact with his namesake animal, the lion, has intrigued modern historians.[1] Known for his largely popular and successful rule over England from 1157 to 1199, as well as his substantial contributions to Christian efforts to reclaim Jerusalem during the Third Crusade, it is assumed that Richard earned his epithet for many reasons including, wrestling with a lion in prison after getting captured by Leopold V of Austria, and his brave and fierce leadership during the third crusade.[2][3] However, no direct confirmation exists that the king laid eyes on an animal itself.

Life of Richard the Lionheart

Early life and childhood

Richard I was born 8 September 1157 in Oxford, England, to King Henry II of England, and his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine.[3] Raised primarily in England, he spoke his mother's native French as well as Limousin, a dialect of Occitan, and it is not known to what degree he spoke English.[4][5] Richard was not the initial heir apparent to Henry II, a title which fell to his older brother, who would be known as Henry the Young King. Through his mother, however, Richard was the heir to the territory of Aquitaine, which he would acquire in 1171.[3][6][7][8][9]

Early political career and revolt against Henry II

Even at an early age Richard proved that he was a sound political and military force, strategically betrothing Alys, Countess of the Vexin, the fourth daughter of Louis VII.[3]He also became known for his military acumen after Henry II enacted his plan to divide the kingdom between his sons until his death, upon which Henry the Young King would assume the throne. The Young King, wishing to reign alone and sovereign immediately, rebelled against his father, and was joined by his brothers Richard and Geoffrey, who met their brother in France under the protection of Louis VII.[3]Some speculate that this rebellion was instigated by Richard's mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine.[3][10][11]

The three brothers swore that they would not conclude any type of peace without the consent of the French King and barons, underscoring the intensity and unforgiving nature of the war.[12]By July 1173 the rebels were besieging Aumale, Neuf-Marché, and Verneuil, and Hugh de Kevelioc had captured Dol in Brittany, significant gains for the rebel brothers.[3]Richard himself was tasked with eliminating his father's supporters from Aquitaine, the possession of which he was now fighting his father for, since his mother had been captured by Richard's father and his allies.[3][12] He suffered a minor defeat at La Rochelle, and withdrew to Saintes to plan his next moves.[3]

While this was happening, Henry II raised a mercenary army of over 20,000 men, with which he began a counterattack on the rebel's newly acquired territory.[3] After finding success retaking both Dol and Brittany, he extended peace offers to his sons, but they unanimously rejected them on the advice of Louis.[3] Subsequently, Henry II attacked Richard at Saintes, and decimated his troops, reclaiming the entirety of the area. Richard escaped with relatively few soldiers, and remained camped in the Chateau de Taillebourg until the end of the war.[3] After briefly returning to England to quell another revolt, led by Henry the Young King and the Earl of Leicester, Henry II returned to France and defeated Louis VII and the Young King in battle, whereupon he secured the surrender of the majority of the rebels in the Treaty of Montlouis.[3][12]

Despite the surrender, the treaty signed between the French and English kings specifically excluded Richard, who was then left at the mercy of his father.[3][12]On September 23, 2003, he returned to England and begged his father for mercy, which was granted, albeit on harsher terms than offered before Henry II's initial invasion of Normandy. [3][12]Richard regained control of Aquitaine to a certain capacity, but his mother Eleanor remained Henry's captive until his death.[3]

Origins of the name

The end of the rebellion seems to be when the sobriquet "Lionheart" came about, as in 1187 Gerald of Wales referred to him as hic leo noster (this our lion) in his account of Richard's fierce punitive mission against his own allies from the revolt, which he did at the behest of his father.[3]It appears that this campaign, where Richard distinguished himself as soldier and commander, earned his comparison to a lion, while the "-heart" may not have been added until 1191, during the Third Crusade.[3][13] It appears this title was given after a particularly fierce castle siege, where he courageously led soldiers crushing the battlements.[3] There are no accounts of Richard traveling beyond England and France prior to this point in his life, and he had yet to embark on his journey to the Middle East, therefore implying that he had not seen a lion at all—and surely not a wild lion—when he earned his title. Richard is also credited with having originated the English crest of a lion statant.[14] The first documented royal coat of arms appear on the Great Seal of Richard I, where he is depicted on horseback with a shield containing one lion on the visible half. Because several of his immediate kin used lion coats, it has been speculated that his father Henry II may likewise have borne a single-lion coat of arms, perhaps with the same colors as later used by the family, a gold lion on red. [15]

Lions in British heraldry

The lion has become a major motif for Britain because of its early uses by King Henry I of England and popularization by Richard the Lionheart in the third crusade.[16][17] The influence of the Lion being used as a symbol or motif can be traced as far back as the Neolithic period.

First uses of the Lion in British heraldry

.svg.png.webp)

King Henry I of England was the first king of England known to use a heraldic design: a signet ring with a lion engraved on it. The design would be altered in later generations to form the Royal Arms of England.[18] Henry was said to have given a badge decorated with a lion to his son-in-law Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. Heraldry is thought to have becoming popular among the knights on the first and second crusades, along with the idea of chivalry.[19][16] One example of this is the seal of John Mundegumri (1175), which bears a single fleur-de-lys.[20] Prior to the 16th century, there was no regulation on the use of arms in England.[21]

Religious influence on British Heralrdy

Prehistoric religions of the Middle East, North India and the Mediterranean, associated lions to a neolithic goddess referred to as Potnia Theron, translated to the 'Mistress of Animals.'[22] In this role, lions became associated with polarities such as the seasons, the zodiacal belt, and with the power of the elite. Importantly, this motif is more common in later Near Eastern and Mesopotamian art with a male figure, called the Master of Animals. Leading to the lion being culturally pictured as a master of the animal kingdom.[23][24] With the incursions of the Indo-European speakers, this association changed. While initially through myths of confrontation between the goddess lions and the hero or demigod. Eventually, it became a direct association between the lion and the male deity, this lead to an association with status and the divine authority of kingship. Lion imagery became associated with the Zoroastrian and Mithraic religions, as well as Judaeo, Christian, and Islamic monotheism. Furthermore, it became central to Hindu and Buddhist beliefs, and in this way, spread eastward along the Silk Road, where Arabs traveled to India and China, Chinese to Central Asia, India, and Iran. Buddhism itself was carried along these roads from India through Central Asia to Tibet, China, and Japan. Islam was carried by Sufi teachers, and by armies, moving across the continent from Western Asia into Iran, Central Asia, and into China and India.[25] As the Silk Road further developed, the imagery of the lion westward with the Roman Empire reaching both China and Britain by the early 1st century. Lion imagery became incorporated into the defining cultural icons of both China and Britain, becoming steadily more populist and taking on culturally specific forms such as European heraldry and the Chinese lion dance. [26]

Cultural significance of Lions in medieval Europe

The development of the modern heraldic language cannot be attributed to a single individual, time, or place. Although certain designs that are now considered heraldic were evidently in use during the eleventh century, most accounts and depictions of shields up to the beginning of the twelfth century contain little or no evidence of their heraldic character. For example, the Bayeux Tapestry, illustrating the Norman invasion of England in 1066, and probably commissioned about 1077, when the cathedral of Bayeux was rebuilt, this was undertaken by Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, and half-brother of William I, whose conquest of England is commemorated by the tapestry. depicts a number of shields of various shapes and designs, many of which are plain, while others are decorated with dragons, crosses, or other typically heraldic figures. Yet no individual is depicted twice bearing the same arms, nor are any of the descendants of the various persons depicted known to have borne devices resembling those in the tapestry.[27][28]

The animals of the "barbarian" (Eurasian) predecessors of heraldic designs are likely to have been used as clan symbols.[29] Adopted in Germanic tradition around the fifth century,[30] they were re-interpreted in a Christian context in the western kingdoms of Gaul and Italy in the 6th and seventh centuries.

During the eleventh century, crosses appearing on seals of Spanish princes and were used for authentication privileges until King Alfonso VII started using a lion (1126), alluding to the name of his main realm lion (Spanish: león), an example of canting arms.[31]

The lion as a heraldic charge is present from the very earliest development of heraldry in the 12th century. One of the earliest known examples of armory as it subsequently came to be practiced decorates the tomb of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, who died in 1151.[32] An enamel, probably commissioned by Geoffrey's widow between 1155 and 1160, depicts him carrying a blue shield with golden lions rampant and wearing a blue helmet adorned with another lion. A chronicle dated to about 1175 states that Geoffrey was given a badge of a gold lion when he was knighted by his father-in-law, Henry I, in 1128.[33][34]

Before Richard I

The first account of lions being held in captivity in England predates Richard I by a half-century. The Lionheart's great-grandfather, William the Conqueror, established a royal menagerie at his estate manor in Woodstock, where he kept a wide variety of exotic animals, although no sources give specific species.[35]His son and successor as ruler of England, Henry I, is recorded as having expanded the menagerie to include lions, among other animals, around the turn of the 12th century.[35]However, neither these lions, nor any of the other animals, are attested to past the reign of Henry I, so it is possible that the menagerie was closed and its animals either dead or escaped during the onset of Angevin rule. It seems unlikely that any animals would have survived from Henry I to Richard I, and without the population being replenished, it seems the local population in England would have died out before Richard's birth in 1157.

After Richard I

Adding some credence to the idea that the menagerie of William the Conqueror and Henry I was not maintained, Richard's successor as king, John, established the Tower Menagerie in 1199, immediately subsequent to his coronation, which of course followed the death of the Lionheart.[36] This menagerie was founded only months after the death of Richard the Lionheart.[3]Since the menagerie was founded, rather than being expanded upon, by John, it can be assumed that the menagerie dating back to William I and Henry I was long gone.

Lyon

The arms of Lyon date back to the Middle Ages, when they were called the Counts of Lyon. The Counts of Lyon added a rampant argent lion on a red field, with a tongue to their coat of arms. The coat of arms of the French city has evolved over time but the lion has always remained since the founding of the Count of Lyons.

Versailles

King of France Louis XIV collected exotic birds and animals at the French palace in Versailles in the seventeenth century; the palace menagerie quickly became well known among the nobility for its wide collection, including lions, and for staging animal fights in arenas complete with an audience.[37]

In the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II had three permanent menageries in Italy, at Melfi in Basilicata, at Lucera in Apulia and at Palermo in Sicily.[38]The collections of animals grew quickly, and although he was known for his avian interests and authoritative books on ornithology, he also had elephants, a white bear, a giraffe, a leopard, hyenas, cheetahs, camels, monkeys and lions.[39]

Kingdom of León

Alfonso VII's use of the lion as a heraldic emblem for León predates the earliest surviving Royal Arms of England, a single lion visible on a half-shield depicted on the First Great Seal (1189) of Richard I,[40] as well as the three pale blue lions passant of Denmark (ca. 1194),[41] the heraldry of the Holy Roman Empire (ca. 1200)[42] and the French fleurs-de-lis coat (1211)[43] although the fleur-de-lis was present on royal robes and ornaments since at least 1179.[44]

(Tumbo A manuscript)

That Alfonso VII took the lion on his banners and arms was due to the dominance of León in the kingdom. When other parts of the Chronica refer to the raising the royal standards in the taken enemy fortress, it is referring to some flags which depicted the lion. It is disputed whether this animal represented to the monarch or kingdom, in the first case the strength of the sovereign but it seems a clearer identification between the words "Legio" and "leo" that would imply the adoption of the feline as image of the city and the kingdom. In favour of the second hypothesis is the fact that in the author of the Chronica made a rhyme with the words "legionis" and "leonis".

Roman Empire

During the Roman empire, the Colosseum in Rome was known for its extravagant events, including intense hunting and fighting scenes where animals including rhinoceros, hippopotamuses, elephants, giraffes, aurochs, wisents, Barbary lions, panthers, leopards, bears, Caspian tigers, crocodiles and ostriches. These animals were imported and usually killed, either by people or in fights with other animals.[46][47][48]Lions brought to Rome would have likely been from the Barbary Coast, or from farther south in Africa.

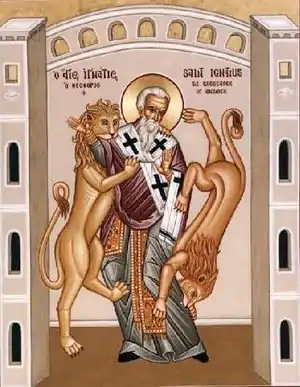

In Early Christianity

Early Christians faced significant persecution in the Roman Empire, and often suffered the death penalty via wild animals. Being chained and eaten be wild lions was a common occurrence under emperors such as Trajan and Hadrian.[46][47][48][49]One such prominent example of a Christian martyr is Ignatius of Antioch, who, according to Greek bishop Irenaeus was fed to lions in Rome in 107 AD.[46][47][48]

In the Book of Revelations, John references a lion that has come from the House of David, presumably referring to Jesus's second coming.[50] This was later adapted into the Lion of Judah, the symbol of the Israelite tribe of Judah.[51]

Renaissance Era

15th century Italian aristocracy began collecting their own animals in private menageries, which often included lions as popular animals. A prominent example of these villa menageries was Villa Borghese, in Rome.[52]

Lions in Arabia

Lions in contemporary Islamic texts

In the Qur'an, Hadith, and Arab poetry the Lion is a common motif used to depict the prophet Muhammad.[55] Verses 50 and 51 of Surat al-Muddaththir in the Quran talk about ḥumur ('asses' or 'donkeys') fleeing from a qaswarah ('lion', 'beast of prey' or 'hunter'). This verse is a criticism of people who were averse to Muhammad's teachings.[56]

What is the matter with them? Why do they turn away from the warning, like stampeding asses fleeing from a lion?

Surat al-Muddaththir criticizes people who were averse to the Islamic Prophet Muhammad's teachings, such as that the rich have an obligation to donate wealth to the poor, comparing their attitude to itself, with the response of prey to a qaswarah (Arabic: قَسْوَرَة, meaning "lion", "beast of prey", or "hunter").[56]

Cultural meaning of lions

.JPG.webp)

Pre-Islamic depictions of lions

Lions are depicted on vases dating to about 2600 before present that were excavated near Lake Urmia in Iran.[57] The lion was an important symbol in Ancient Iraq and is depicted in a stone relief at Nineveh in the Mesopotamian Plain.[58][59] Having occurred in the Arab world, particularly the Arabian Peninsula, the Asiatic lion has significance in Arab and Islamic culture.

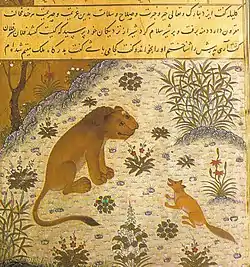

The lion of Babylon is a statue at the Ishtar Gate in Babylon The lion has an important association with the figure Gilgamesh, as demonstrated in his epic.[60] The symbol of the lion is also closely tied to the Persian people. Achaemenid kings were known to carry the symbol of the lion on their thrones and garments. The Shir-va-Khorshid (Persian: شیر و خورشید, "Lion and Sun") is one of the most prominent symbols of Iran, dating back to the Safavid dynasty, and having been used on the flag of Iran, until 1979.[61] In Persian and in Indian literature, the lion is rivaled by the tiger. This is demonstrated in the book Anvar-i-Suhayli (Persian: اَنوارِ سُهيلى, "Lights of the Canopus").[62]

Islamic depictions of lions

In Muhammad's first revelation, the divine voice from Allah on the mountain Jabal an-Nour, near Mecca, has been compared to that of a roaring lion by Muslim historians. [63][64] In Islamic tradition the phrase "the lion will lie down with the lamb" is used to describe the Judgment day event where peace will be constituted by a just ruler. Big cats like the asad (lion), namir (نَمِر, leopard), and namur (نَمُر, Tiger), can symbolize ferocity, similar to the wolf. Apart from ferocity, the lion has an important position in Islam and Arab culture. Men noted for their bravery, like Ali,[65] Hamzah ibn Abdul-Muttalib[66] and Omar Mukhtar,[67] were given titles like "Asad Allāh" ("Lion of God") and "Asad aṣ-Ṣaḥrāʾ" ("Lion of the Desert"). Other Arabic words for 'lion' include sabaʿ (Arabic: سَبَع),[68]. An Arabic toponym for the Levantine City of Beersheba (Arabic: بِئر ٱلسَّبَع) can mean "Spring of the Lion".[69][70][53][54][71][72][73][74][75][76]

References

- Ambrisco, Allan. "Cannibalism and cultural encounters in Richard Coeur de Lion". Pro Quest. Duke University Press Fall 1999. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Richard the Lionheart Biography". www.medieval-life-and-times.info. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- Flori, Jean (1999). Richard Coeur de Lion : le roi-chevalier. Paris: Payot et Rivages. ISBN 2-228-89272-6. OCLC 300452562.

- Gillingham 2002, p. 52.

- Leese, Thelma Anna (1996). Blood royal : issue of the kings and queens of medieval England, 1066-1399 : the Normans and Plantagenets. Bowie, Md.: Heritage Books. ISBN 0-7884-0525-X. OCLC 35870708.

- Giraldi Cambrensis topographia Hibernica, dist. III, cap. L; ed. James F. Dimock in: Rolles Series (RS), Band 21, 5, London 1867, S. 196.

- Slatyer, Will (2012). Ebbs and Flows of Medieval Empires, Ad 900–1400: A Short History of Medieval Religion, War, Prosperity, and Debt. Partridge Publishing Singapore. ISBN 9781482894554.

- Hilton, Lisa (2010). Queens Consort: England's Medieval Queens. Hachette UK. ISBN 9780297857495.

- Hilliam, David (2004). Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Richest Queen in Medieval Europe. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 83. ISBN 9781404201620.

- L'Estoire de la Guerre Sainte, v. 2310, ed. G. Paris in: Collection de documents inédits sur l'histoire de France, vol. 11, Paris 1897, col. 62.

- Roger of Hoveden & Riley 1853, p. 64

- Gillingham, John (2002). Richard I (Paperback ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09404-3. OCLC 48930315.

- "Medieval Life and Times". medieval-life-and-times.info. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 37

- Pastoureau (1997), p. 59

- Boutell (1914), p. 9.

- "English etymology of Heraldry". myEtymology. Jim Sinclair. Archived from the original on 2009-07-26. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- Vincent (2007b), p. 324.

- James Ross Sweeney (1983). "Chivalry", in The Dictionary of the Middle Ages, Volume III.

- Illustrated in Boutell (1914), pp. 10–11.

- François R. Velde. "Regulation of Heraldry in England". Heraldica. Archived from the original on 2008-09-15. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- "Homer, Iliad, Book 21, line 468". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

Tὸν δὲ κασιγνήτη μάλα νείκεσε πότνια θηρῶν Ἄρτεμις ἀγροτέρη, καὶ ὀνείδειον φάτο μῦθον...

- Fischer-Hansen, Tobias; Birte Poulsen (2009). From Artemis to Diana: the goddess of man and beast. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-8763507882.

- Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean world. Cambridge University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-521-29037-1.

- Kurin, Richard. "THE SILK ROAD: CONNECTING PEOPLE AND CULTURES". Smithsonian Folklife Festival. Smithsonian. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Feltham, Heleanor. "Here be lions: an investigation into the origin, distribution, meaning and transformation of lion imagery". Open Publications of UTS Scholars. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- John Woodward and George Burnett, A Treatise on Heraldry: British and Foreign, W. & A. K. Johnson, Edinburgh and London (1892), vol. 1, pp. 29–31.

- Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, pp. 14–16.

- "They [animal style designs] have also been explained as totems venerated by the various clans of nomads as ancestors. Their transformation into clan symbols would have followed naturally and easily. The heraldic beasts of medieval chivalry, which include many deer and felines like those on the British royal coat of arms, may certainly be traces back to emblematic devices of later barbarian tribes from central Asia" Hugh Honour, John Fleming, A World History of Art (2005), p. 166.

- Danuta Shanzer, Ralph W Mathisen (2013) Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity, p. 322.

- The actual etymology of León is Roman legion.

- Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, p. 62.

- C. A. Stothard, Monumental Effigies of Great Britain (1817) pl. 2, illus. in Anthony Wagner, Richmond Herald, Heraldry in England, Penguin (1946), pl. I.

- Michel Pastoureau, Heraldry: An Introduction to a Noble Tradition, Thames and Hudson Ltd. (1997), p. 18.

- Blunt, Wilfrid (1976). The ark in the park : the Zoo in the nineteenth century. London: Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-89331-3. OCLC 2426306.

- "Big cats prowled London's tower". 2005-10-24. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- Robbins, Louise E. (2002). Elephant slaves and pampered parrots : exotic animals in eighteenth-century Paris. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7677-X. OCLC 51481138.

- Friese, Carrie (2013-09-02). Cloning Wild Life. NYU Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9780814729083.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-8147-2908-3.

- New worlds, new animals : from menagerie to zoological park in the nineteenth century. Hoage, R. J., Deiss, William A., National Zoological Park (U.S.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 1996. ISBN 0-8018-5110-6. OCLC 32821216.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Ailes, Adrian (1982). The Origins of The Royal Arms of England. Reading: Graduate Center for Medieval Studies, University of Reading. pp. 52–3, 64–74.

- Bartholdy, Nils G. (1995). Denmark's Arms and Crown (in Danish). Copenhagen: Ministry of Culture. p. 16. ISBN 87-87361-20-5. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Diem, P. "Die Entwicklung des österreichischen Doppeladlers" (in German). Fr.wikisource.org. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Pastoureau, Michel (1997). Heraldry: An Introduction to a Noble Tradition. "Abrams Discoveries" series. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 100. ISBN 0-500-30074-7.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles: A Complete Guide to Heraldry, Nueva York, Elibron Classics, 2006. P. 274 ISBN 0-543-95814-0. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Tumbo A Manuscript (Santiago de Compostela Cathedral)

- Flinn, Frank K. (2007). Encyclopedia of Catholicism. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-7565-2. OCLC 191044725.

- Litfin, Bryan M., 1970- (2007). Getting to know the church fathers : an evangelical introduction. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1-4412-4740-7. OCLC 608524795.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Brockman, Norbert C., 1934-2013. (2011). Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-655-3. OCLC 763159270.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Litfin, Bryan M., 1970- (2007). Getting to know the church fathers : an evangelical introduction. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1-4412-4740-7. OCLC 608524795.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Revelation 5:5 Then one of the elders said to me, "Do not weep! Behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has triumphed to open the scroll and its seven seals."". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- "Genesis 49:9 Judah is a young lion--my son, you return from the prey. Like a lion he crouches and lies down; like a lioness, who dares to rouse him?". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- Baratay, Éric. (2002). Zoo : a history of zoological gardens in the West. Hardouin-Fugier, Elisabeth. London: Reaktion. ISBN 1-86189-111-3. OCLC 48837034.

- The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 14. Charles Knight and Co. 1846-01-09. Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- Charles Knight, ed. (1867). The English Cyclopaedia. Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- "Image of Lion & Prominent Jihadists". Combatting Terrorism Center. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Quran 74:41–51

- Gesché‐Koning, N. & Van Deuren, G. (1993). Iran. Bruxelles, Belgium: Musées Royaux D'Art et D'Histoire.

- Scarre, C. (1999). The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Ashrafian, H. (2011). "An extinct Mesopotamian lion subspecies". Veterinary Heritage. 34 (2): 47–49.

- Dalley, S., ed. (2000). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953836-2.

- Shahbazi, S. A. (2001). "Flags (of Persia)". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 10. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- Eastwick, Edward B (transl.) (1854). The Anvari Suhaili; or the Lights of Canopus Being the Persian version of the Fables of Pilpay; or the Book Kalílah and Damnah rendered into Persian by Husain Vá'iz U'L-Káshifí. Hertford: Stephen Austin, Bookseller to the East-India College.

- Weir, T.H.; Watt, W. Montgomery (2012-04-24). "Ḥirāʾ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill Online. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Kinderman, H. "al-Asad". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. "Ali". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- Muhammad ibn Saad. Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabair vol. 3. Translated by Bewley, A. (2013). The Companions of Badr. London: Ta-Ha Publishers.

- As-Salab, Ali Muhammad (2011). Omar Al Mokhtar Lion of the Desert (The Biography of Shaikh Omar Al Mukhtar). Al-Firdous. p. 1. ISBN 978-1874263647.

- Pease, A. E. (1913). The Book of the Lion. London: John Murray.

- Qumsiyeh, Mazin B. (1996). Mammals of the Holy Land. Texas Tech University Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 0-8967-2364-X.

- Muhammad ibn Saad (2013). The Companions of Badr. Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabair. 3. Translated by Bewley, A. London: Ta-Ha Publishers.

- Kinnear, N. B. (1920). "The past and present distribution of the lion in south eastern Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 27: 34–39. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- Smith, C.H. (1842). "The lion Felis Leo − Auctorum". In Jardine, W. (ed.). The Naturalist's Library. Vol. 15 Mammalia. London: Chatto and Windus. p. Plate X, 85.

- John Hampden Porter (1894). "The Lion". Wild beasts; a study of the characters and habits of the elephant, lion, leopard, panther, jaguar, tiger, puma, wolf, and grizzly bear. pp. 76–135. Retrieved 2014-01-19. A reference to the lion in the region of Pilgrimage is in a hadith.

- Muwatta’ Imam Malik, Book 20 (Hajj), Hadith 794

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. "Ali". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- Muhammad ibn Saad (2013). "The Companions of Badr". Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabair. 3. Translated by Bewley, A. London: Ta-Ha Publishers.