Rurik dynasty

The Rurik dynasty, or Rurikids (Russian: Рю́риковичи, romanized: Rjúrikoviči, IPA: [ˈrjʉrʲɪkəvʲɪt͡ɕɪ]; Ukrainian: Рю́риковичі, romanized: Rjúrykovyči; Belarusian: Ру́рыкавічы, romanized: Rúrykavičy, literally "sons/descendants of Rurik"), was a dynasty founded by the Varangian[1] prince Rurik, who established himself in Novgorod around the year AD 862.[2] The Rurikids were the ruling dynasty of Kievan Rus' (after conquest of Kiev by Oleg of Novgorod in 882 ), as well as the successor principalities of Vladimir-Suzdal, Ryazan, Smolensk, Galicia-Volhynia (after 1199), Chernigov, and the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Ivan the Great united Rus's principalities under Grand Duchy of Moscow and ruled it as Prince of all Rus.[3] It was later transformed into Tsardom of Rus (Tsardom of Russia). They ruled until 1610 and the Time of Troubles, following which they were succeeded by the Romanovs. They are one of Europe's oldest royal houses, with numerous existing cadet branches.

| Rurik dynasty Рю́риковичи Rurikids | |

|---|---|

| Royal dynasty | |

.png.webp) Personal seal of Yaroslav the Wise | |

| Country | |

| Founded | 862 (in Great Novgorod) |

| Founder | Rurik |

| Final ruler | Vasili IV of Russia |

| Titles |

Princely titles

|

| Style(s) | |

| Estate(s) | |

| Deposition | 1610 (in Moscow, Tsardom of Russia) |

| Cadet branches |

|

As a ruling dynasty, the Rurik dynasty held its own in some part of Russia for a total of twenty-one generations in male-line succession, from Rurik (died 879) to Feodor I of Russia (died 1598), a period of more than 700 years. Russian Empress Catherine the Great referred to her Rurikid ancestry.[4]

Origins

The Rurikid dynasty was founded in 862 by Rurik, a Varangian prince. The scholarly consensus [5] is that the Rus' people originated in what is currently coastal eastern Sweden around the eighth century and that their name has the same origin as Roslagen in Sweden (with the older name being Roden).[6][7][8] According to the prevalent theory, the name Rus', like the Proto-Finnic name for Sweden (*Ruotsi), is derived from an Old Norse term for "the men who row" (rods-) as rowing was the main method of navigating the rivers of Eastern Europe, and that it could be linked to the Swedish coastal area of Roslagen (Rus-law) or Roden, as it was known in earlier times.[9][10] The name Rus' would then have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: Ruotsi and Rootsi.[10][11]

The Primary Chronicle gives the following account of how the Rurik dynasty began, dating it to the Byzantine years of the world 6368-6370 (AD 860-862):[12]

The tributaries of the Varangians drove them back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves. There was no law among them, but tribe rose against tribe. Discord thus ensued among them, and they began to war one against another. They said to themselves, "Let us seek a prince who may rule over us and judge us according to the Law." They accordingly went overseas to the Varangian Russes: these particular Varangians were known as Russes, just as some are called Swedes, and others Normans, English, and Gotlanders, for they were thus named. The Chuds, the Slavs, the Krivichians, and the Ves' then said to the people of Rus', "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us." They thus selected three brothers, with their kinsfolk, who took with them all the Russes and migrated. The oldest, Rurik, located himself in Novgorod; the second, Sineus, at Beloozero; and the third, Truvor, in Izborsk. On account of these Varangians, the district of Novgorod became known as the land of Rus'. The present inhabitants of Novgorod are descended from the Varangian race, but aforetime they were Slavs [преже бо бѣша Словѣни].

There is some ambiguity even in the Primary Chronicle about the specifics of the story, "hence their paradoxical statement 'the people of Novgorod are of Varangian stock, for formerly they were Slovenes.'" However, archaeological evidence such as "Frankish swords, a sword chape and a tortoiseshell brooch" in the area suggest that there was, in fact, a Scandinavian population during the tenth century at the latest.[13]

History

Rurik and his brothers founded a state that later historians called Kievan Rus′. By the middle of the twelfth century, Kievan Rus′ had dissolved into independent principalities, each ruled by a different branch of the Rurik dynasty. The dynasty followed agnatic seniority and the izgoi principle. The Rurik dynasty underwent a major schism after the death of Yaroslav the Wise in 1054, dividing into three branches on the basis of descent from three successive ruling Grand Princes: Izyaslav (1024–1078), Svyatoslav (1027–1076), and Vsevolod (1030–1093). In addition, a line of Polotsk princes assimilated themselves with the princes of Lithuania. In the 10th century the Council of Liubech made some amendments to a succession rule and divided Ruthenia into several autonomous principalities that had equal rights to obtain the Kiev throne.

Vsevolod's line eventually became better known as the Monomakhovichi and was the predominant one. The line of Svyatoslav later became known as Olegovychi and often laid claim to the lands of Chernihiv and Severia. The Izyaslavychi who ruled Turov and Volhynia were eventually replaced by a Monomakhovychi branch.

"The Rurikid dynasty ... attempted to impose on their highly diverse polity the integrative concept of russkaia zemlia ('the Rus′ land') and the unifying notion of a 'Rus′ people'. But 'Kievan Rus′' was never really a unified polity. It was a loosely bound, ill-defined, and heterogeneous conglomeration of lands and cities inhabited by tribes and populous groups whose loyalties were primarily territorial." This caused the Rurik dynasty to effectively dissolve into several sub-dynasties ruling smaller states in the 10th and 11th centuries. These were the Olgoviches of Severia who ruled in Chernigov, Yuryeviches who controlled Vladimir-Suzdal, and Romanoviches in Galicia-Volhynia.[15][16]

Descendants of Sviatoslav II of Kiev

The Olgoviches descended from Oleg I of Chernigov, a son of Sviatoslav II of Kiev and grandson of Yaroslav the Wise. They continued to rule until the early 14th century when they were torn apart by the emerging Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Grand Duchy of Moscow. The line continued through Oleg's son Vsevolod II of Kiev, grandson Sviatoslav III of Kiev, great-grandson Vsevolod IV of Kiev and great-great grandson Michael of Chernigov, from whose sons the extant lines of the Olegoviches are descended, including the Massalsky, Gorchakov, Baryatinsky, Volkonsky and Obolensky, including Repnin.

Descendants of Vsevolod I of Kiev

Vsevolod I of Kiev was the father of Vladimir II Monomakh, giving rise to the name Monomakh for his progeny. Two of Vladimir II's sons were Mstislav I of Kiev and Yuri Dolgorukiy.

The Romanoviches (Izyaslavichi of Volhynia) were the line of Roman the Great, descended from Mstislav I of Kiev through his son Iziaslav II of Kiev and his grandson Mstislav II of Kiev, father of Roman the Great. The older Monomakhovychi line that ruled Principality of Volhynia, they were eventually crowned kings of Galicia and Volhynia and ruled until 1323. Romanovychi displaced the older line of Izyaslavychi from Turov and Volhynia as well as Rostyslavychi from Galicia. The last were two brothers of Romanovychi, Andrew and Lev II, who ruled jointly and were slain trying to repel Mongol incursions. The Polish king, Władysław I the Elbow-high, in his letter to the Pope wrote with regret: "The two last Ruthenian kings, that had been firm shields for Poland from the Tatars, left this world and after their death Poland is directly under Tatar threat." Losing their leadership role, Rurikids, however, continued to play a vital role in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the later Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Most notably, the Ostrogski family held the title of Grand Hetman of Lithuania and strove to preserve the Ruthenian language and Eastern Orthodoxy in this part of Europe. It is thought that the Drutsk and related princely families may also descend from Roman the Great.

The Rostislaviches were the line of Rostislav I of Kiev, another son of Mstislav I of Kiev, who was Prince of Smolensk and a progenitor of the lines descending from the princes of Smolensk and Yaroslavl.

The Shakhovskoys were founded by Konstantin "Shakh" Glebovich, Prince of Yaroslavl, and traces its lineage to Rostislav I of Kiev through his son Davyd Rostislavich. This branch also descends cognatically of Ivan I of Moscow, through the latter's daughter Evdokia Ivanovna Moskovskaya (1314–1342),[17] who married Vasili Mikhailovich, Prince of Yaroslavl (died 1345).[18] They were the great-grandparents of Andrej and Jurij, the first Shakhovskoy princes. This is possibly the most senior extant branch of the Rurikids, with many Shakhovskoys living outside of Russia after having fled during the Russian Revolution.

The Yuryeviches were founded by Yuriy Dolgorukiy, the founder of Moscow and spread vastly in the north-east. Yuri's son Vsevolod the Big Nest was Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal, a precursor state to the Grand Principality of Moscow and thus of the Russian Empire. Vsevolod's son Konstantin of Rostov was Prince of Rostov and the progenitor of various "Rostov" princely lines. Another son, Ivan Vsevolodich, was Prince of Starodub and progenitor of a number of extant lines, most notably the Gagarin line.

Vsevolod's son Yaroslav II of Vladimir was the father of Alexander Nevsky, whose son Daniel of Moscow sired the ruling house of Moscow until the end of the 16th century.

Beginning with the reign of Ivan the Terrible, the Muscovite branch used the title "Tsar of All Russia" and ruled over the Tsardom of Russia. The death in 1598 of Tsar Feodor I ended the rule of the Rurik dynasty. The dynasty was briefly revived in the person of Vasili IV of Russia, a descendant of Shuyskiy line of the Rurik dynasty, but he died without issue. The unstable period known as the Time of Troubles succeeded Feodor's death and lasted until 1613.

In that year, Mikhail I ascended the throne, founding the Romanov dynasty that would rule until 1762 and as Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov until the revolutions of 1917. Tsar Mikhail's father Patriarch Filaret of Moscow was descended from the Rurik dynasty through the female line. His mother, Evdokiya Gorbataya-Shuyskaya, was a Rurikid princess from the Shuysky branch, daughter of Alexander Gorbatyi-Shuisky. Tsar Mikhail's first wife Maria Dolgorukova was of Rurikid stock but their marriage produced no children. Emperor Peter III in 1762 brought fresh Rurikid blood to the Romanovs: he and his wife Catherine the Great both descended from the Rurik dynasty. (Catherine the Great descended from a daughter of Yaroslav I (978–1054) through her maternal grandfather, Christian August of Holstein-Gottorp.[19])

Historian Vasily Tatishchev and filmmaker Jacques Tati also descended from Rurik.

Trade

In the early days of the Rurikid dynasty, the Kievan Rus' mainly traded with other tribes in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia. "There was little need for complex social structures to carry out these exchanges in the forests north of the steppes. So long as the entrepreneurs operated in small numbers and kept to the north, they did not catch the attention of observers or writers." The Rus' also had strong trading ties to Byzantium, particularly in the early 900s, as treaties in 911 and 944 indicate. These treaties deal with the treatment of runaway Byzantine slaves and limitations on the amounts of certain commodities such as silk that could be bought from Byzantium. The Rus' used log rafts floated down the Dnieper River by Slavic tribes for the transport of goods, particularly slaves to Byzantium.[20]

Skirmish with Byzantium

One of the largest military accomplishments of the Rurikid dynasty was the attack on Byzantium in 960. Pilgrims of the Rus' had been making the journey from Kiev to Constantinople for many years, and Constantine Porphyrogenitus, the Emperor of the Byzantine Empire, believed that this gave them significant information about the arduous parts of the journey and where travelers were most at risk, as would be pertinent for an invasion. This route took travelers through domain of the Pechenegs, journeying mostly by river. In June 941, the Rus' staged a naval ambush on Byzantine forces, making up for their smaller numbers with small, maneuverable boats. These boats were ill-equipped for the transportation of large quantities of treasure, suggesting that looting was not the goal. The raid was led, according to the Primary Chronicle, by a king called Igor. Three years later, the treaty of 944 stated that all ships approaching Byzantium must be preceded by a letter from the Rurikid prince stating the number of ships and assuring their peaceful intent. This not only indicates fear of another surprise attack, but an increased Kievan presence in the Black Sea.[21]

Legacy

Russian and Ukrainian historians have debated for many years about the legacy of the Rurikid dynasty. The Russian view sees the Principality of Moscow ruled by the Rurikid dynasty as the sole heir to the Kievan Rus' civilization, this view is "resting largely on religious-ecclesiastical and historical claims" because Russia was ruled by the Rurikid dynasty until 16th century, while Ukraine was not defined as a state until 20th century. This view started in Moscow as ruled by the original Rurikid dynasty between the 1330s and the late 1850s. The Ukrainian view was formulated much later, between the 1840s and the end of the 1930s in Eastern Austria, and views the Ukrainian descendants of the Rurikid dynasty as its only true successors. The Soviet theory "allotted equal rights to the Kievan inheritance to the Three Slavic peoples, that is the Russians, the Ukrainians, and the Belorussians".[22]

There are currently various extant branches of the Rurikids, for instance: the Houses of Shakhovskoy, Gagarin, and Lobanov-Rostovsky. Whose some of the representatives are: Prince Dmitriy Mikhailovich Shakhovskoy (born 1934), Prince Dmitri Andreevich Gagarin (born 1973) and Prince Nikita Lobanov-Rostovsky (born 1935), a descendant of Prince Konstantin Vasilyevich of Rostov. The three of them are of the Monomakhovichi branch.[23] While the Shakhovskoys claim descent from Mstislav I of Kiev, the Gagarins, and the Lobanov-Rostovskys are descendants of Vsevolod III of Vladimir, which makes the Shakhovskoys the most senior.

Branches

- Izyaslavichi of Polotsk, princes of Polotsk

- Izyaslavichi of Turov, princes of Turiv and Volhynia

- Monomakhovichi, princes of Pereyaslav

- Izyaslavichi of Monomakh, princes of Volhynia, kings of Rus (senior branch)

- Rostislavichi, princes of Smolensk (middle branch)

- Yurievichi, princes of Vladimir-Suzdal, Grand Princes of Moscow (junior branch)

- Shakhovskoy, princes of Yaroslavl (senior extant branch)

- Lobanov-Rostovsky, princes of Rostov (middle extant branch)

- Gagarin, princes of Starodub-on-the-Klyazma (junior extant branch)

- Kilkhov, princes of Starodub-on-the-Klyazma (junior extant branch)

- Olgovichi, princes of Chernihiv

- Rostislavichi of Halych, princes of Halych

- Kropotkin, princes Kropotkin (extant)

- Rzhesvsky, non-titled (exatant)

- Putyatin, princes Putyatin (extant)

- Obolensky, princes Obolensky (extant)

- Gorchakov, princes Gorchakov (extant)

- Vadbosky, a branch of the princes Belozersky (extant)

- Volkonsky, a branch of the princes of Tarusa (extant)

- Possibly the Wiśniowiecki family, a branch of the House of Zbaraski (extant)[24]

Family tree (from Rurik to Vladimir I)

| Rurik | Efanda of Novgorod | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Igor of Kiev | Olga of Kiev | Malk Lubchanin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predslava | Sviatoslav I | Malusha | Rogvolod | Dobrynya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oleg | Yaropolk I | Greek nun | Anna Porphyrogenita | Vladimir I the Great | Rogneda of Polotsk | Konstantin Dobrynich | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| daughter of Bolesław I Chrobry | Sviatopolk I | Theofana | 8 issues (see below) | Dobrynich line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wives and children of Vladimir I (1)

| Olof Skötkonung | Estrid of the Obotrites | Rogneda of Polotsk | Vladimir I the Great | Adela | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saint Anna | Yaroslav the Wise | Izyaslav of Polotsk | Mstislav | Vsevolod | Premislava | Mstislava | Predslava | Mstislav of Chernigov | Boris | Gleb | Stanislav | Sudislav | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 children | Polotsk line | Eustaphius | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wives and children of Vladimir I (2)

| Olava | Vladimir I the Great | Malfrida | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vysheslav | Sviatoslav | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wives and children of Vladimir I (3)

| granddaughter of Otto I the Great | Vladimir I the Great | unknown mistress | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Casimir I duke of Poland | Maria Dobroniega | Bernard margrave of Nordmark | out-of-wedlock daughter | Pozvizd | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From Vladimir I the great to Yuri I Long-arm

- Vladimir the Great

- Yaroslav the Wise, son of Vladimir I the Great

- Vsevolod I of Kiev, son of Yaroslav the Wise

- Vladimir II Monomakh, son of Vsevolod I of Kiev

- Yuri I "Dolgorukiy", i.e. Yuri I Long-arm

- The lineage from Yuri I Long-arm onwards is given in the table below

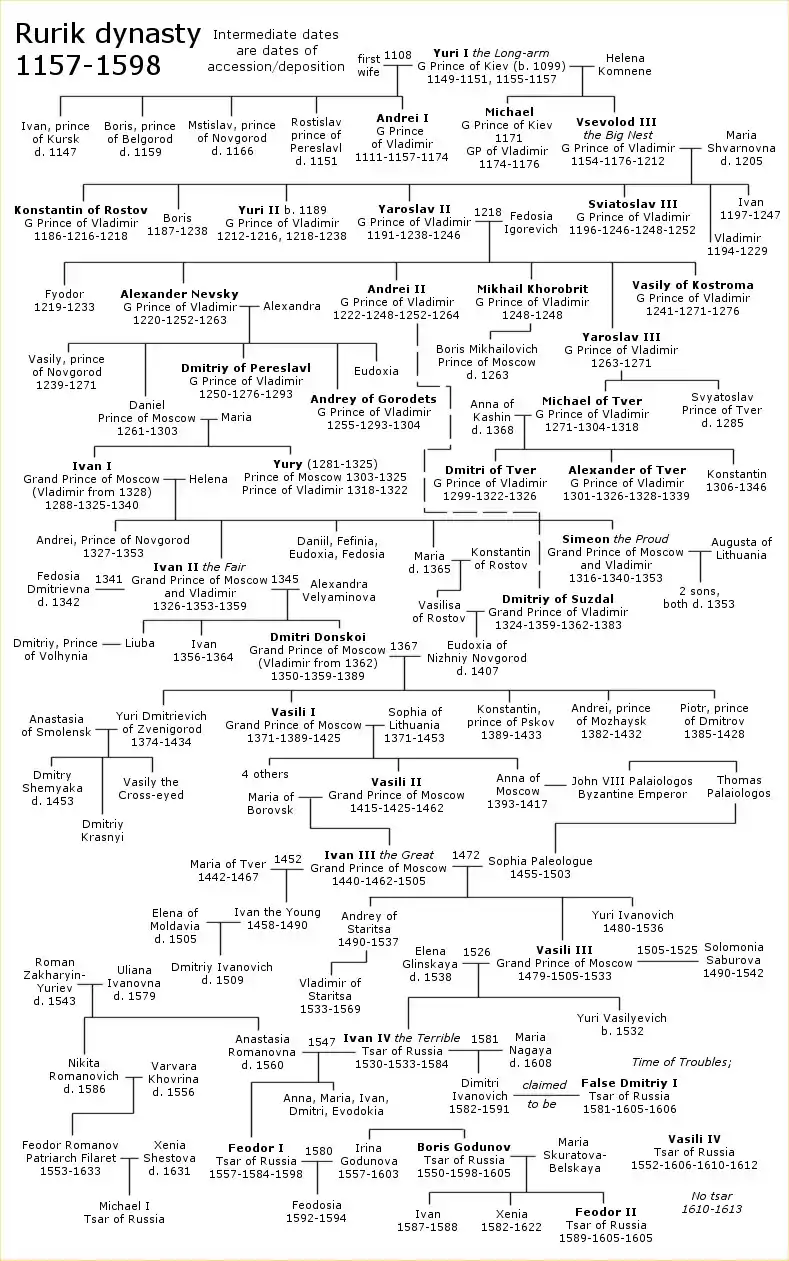

Yuri the Long-arm onwards

The following image shows the descent of the leading (historically most powerful branch) of the Rurikids, being the descendants of Vladimir II Monomakh through his sixth son Yuri Dolgorukiy (known as "Yuri I" and "Yuri Long-arm"):

Family tree of members

Gallery

Coat of arms of the Dolgoruky family

Coat of arms of the Dolgoruky family Coat of arms of the Belosselsky-Belozersky family

Coat of arms of the Belosselsky-Belozersky family Coat of arms of the Kropotkin family

Coat of arms of the Kropotkin family

Gagarin family / Khilkoff Coat of arms

Gagarin family / Khilkoff Coat of arms Coat of arms of the Gorchakov family

Coat of arms of the Gorchakov family Coat of arms of the Mosalsky family

Coat of arms of the Mosalsky family Coat of arms of the Ostrogski family

Coat of arms of the Ostrogski family

Coat of arms of the Shuyski family

Coat of arms of the Shuyski family

References

- Rurik (Norse leader) Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Rurik Dynasty (medieval Russian rulers) Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Grey, Ian (1964-01-01). IVAN III AND THE UNIFICATION OF RUSSIA (First ed.). English Universities Press.

- Editors, History com. "Romanov Family". HISTORY. Retrieved 2020-12-22.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "The Vikings at home". HistoryExtra. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "Kievan Rus". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "The Vikings (780–1100)". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- "Viking Tours Stockholm, 20 Historical Cultural Transported Tours". Sweden History Tours. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Blöndal, Sigfús (1978). The Varangians of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521035521. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Stefan Brink, 'Who were the Vikings?', in The Viking World, ed. by Stefan Brink and Neil Price (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), pp. 4-10 (pp. 6-7).

- "Russ, adj. and n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/169069. Accessed 12 January 2021.

- The Russian Primary Chronicle, translated by Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd Sherbowitz-Wetzor, pp. 59-60. For original, see here.

- Franklin, Simon, and Jonathan Shepherd. The Emergence of Rus 750–1200. Harlow, Essex: Longman Group, Ltd., 1996. pp. 38–39

- Zhukovskyi, Arkadii (2009-12-01). "Encyclopedia of Ukraine". Entsykpopedychnyi Visnyk Ukrainy [The Encyclopedia Herald of Ukraine]. 1: 14–22. doi:10.37068/evu.1.2. ISSN 2707-000X.

- Pelenski, Jaroslaw Pelenski. The Contest for the Legacy of Kievan Rus′. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. p. 4

- Raffensperger, Christian, and Norman W. Ingham, "Rurik and the First Rurikids", The American Genealogist, 82 (2007), 1–13, 111–119.

- Averyanov K. Principality of Moscow under Ivan Kalita (Accession of Koloman. Acquisition of Mozhaisk). - M., p. 36, 1994.

- Voronov A.A. Spaso-Preobrazhensky monastery in the forest // Monasteries of the Moscow Kremlin . - M .: Publishing house Pravosl. St. Tikhon's humanist. un-ta, 2009 .-- 160 p. - ISBN 978-5-7429-0350-5.

- "Byloe Rossii" [Ancestry of Catherine II the Great, Russian Empress 1729–1796: Descent from Rurik (c. 835–879), Prince of Novgorod] (in Russian). The Past of Russia. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- Franklin, Simon, and Jonathan Shepherd (1996). The Emergence of Rus 750–1200. Harlow, Essex: Longman Group, Ltd., pp. 27–28, 127

- Franklin, Simon, and Jonathan Shepherd (1996). The Emergence of Rus 750–1200. Harlow, Essex: Longman Group, Ltd. pp. 112–119

- Pelenski, Jaroslaw Pelenski (1998). The Contest for the Legacy of Kievan Rus'. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 2

- Manaev, G. (2019-07-08). "Who founded Russia and ruled it before the Romanovs?". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- Jerzy Jan Lerski; Piotr Wróbel; Richard J. Kozicki (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing. p. 654. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rurik Dynasty. |