Russian conquest of Central Asia

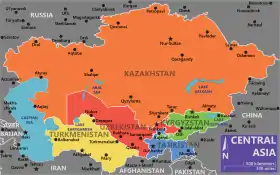

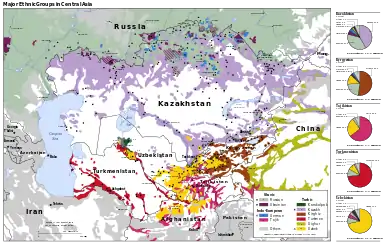

The Russian conquest of Central Asia took place in the second half of the nineteenth century. The land that became Russian Turkestan and later Soviet Central Asia is now divided between Kazakhstan in the north, Uzbekistan across the center, Kyrgyzstan in the east, Tajikistan in the southeast and Turkmenistan in the southwest. The area was called Turkestan because most of its inhabitants spoke Turkic languages with the exception of Tajikistan, which speaks an Iranian language.

| Russian Conquest of Central Asia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Expansion of Russia | |||||||||

Map of Russia, Central-Asian part, 1903 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Kazakh Khanate (until 1848) Khiva Khanate (until 1868) Turkmen Tribes Kyrgyz Tribes | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Ormon Khan |

Kazakh Khanate: Kenesary Khan † Khiva Khanate: Allah Quli Bahadur Abu al-Ghazi Muhammad Amin Bahadur Qutlugh Muhammad Murad Bahadur Sayyid Muhammad Muhammad Rahim Bahadur II Turkmen Tribes: Berdi Murad Khan † Kara Bateer † Kyrgyz Tribes: Kurmanjan Datka | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

5,000 troops 10,000 camels In 1853: 2,000+ troops In 1864: 2,500 troops In 1873: 13,000 troops In 1879: 3,500 troops In 1881: 7,100 troops In 1883–1885: 1,500 troops |

~12,000 troops In 1865: ~36,000 troops | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1,054 killed or died of diseases In 1866: 500 killed and wounded In 1879: 200+ killed ~250 wounded In 1881: 59–268 killed 254–669 wounded 645 died of diseases In 1885: 11 killed or wounded |

230+ killed In 1875: thousands killed 12 000 killed In 1868: 3 500+ killed Turkmen tribes: In 1879: 2,000+ killed 2,000+ wounded In 1881: ~8,000 killed (incl. civilians) ~900 killed or wounded | ||||||||

Outline

In the eighteenth century Russia gained increasing control over the Kazakh Steppe. In 1839 they failed to conquer the Khanate of Khiva south of the Aral Sea. In 1847–53 they built a line of forts from the north side of the Aral Sea eastward up the Syr Darya river. In 1847–64 they crossed the eastern Kazakh steppe and built a line of forts along the northern border of Kyrgyzstan. 1864–68 they moved south from Kyrgyzstan, captured Tashkent and Samarkand and dominated the Khanates of Kokand and Bokhara. They now held a triangle whose southern point was 1,600 km (990 mi) south of Siberia and 1,920 km (1,190 mi) southeast of their supply bases on the Volga River. The next step was to turn this triangle into a rectangle by crossing the Caspian Sea. In 1873 they conquered Khiva. In 1881 they took western Turkmenistan. In 1884 the Merv oasis and eastern Turkmenistan were taken. In 1885 expansion south toward Afghanistan was blocked by the British. In 1893–95 they occupied the high Pamir Mountains in the southeast.

Geography

.svg.png.webp)

White areas are thinly-populated desert.

The three northwest-tending lines are the Kopet Dagh mountains and the Oxus and Jaxartes Rivers flowing from the eastern mountains into the Aral Sea.

The area was bounded on the west by the Caspian Sea, on the north by the Siberian forests and on the east by the mountains along the former Sino-Soviet border. The southern border was political rather than natural. It was about 2,100 km (1,300 mi) from north to south, 2,400 km (1,500 mi) wide in the north and 1,400 km (900 mi) wide in the south. Because the southeast corner (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) is mountainous the flat desert-steppe country is only about 1,100 km (700 mi) wide in the south. Using modern borders, the area was 4,003,400 km2 (1,545,730 sq mi), about half the size of the United States without Alaska. On the east side two mountain ranges project into the desert. Between them is the well-populated Fergana Valley which is approximately the "notch" on the west side of Kyrgyzstan. North of this projection the mountain-steppe boundary extends along the north border of Kyrgyzstan about 640 km (400 mi) before the mountains turn north again.

Rainfall decreases from north to south. Dense population, and therefore cities and organized states, requires irrigation. Streams coming down from the eastern mountains support a fairly dense population, especially in the Ferghana Valley. There is a line of oases along the Persian border. The interior is watered by three great rivers. The Oxus or Amu Darya rises on the Afghan border and flows northwest into the Aral Sea, forming a large delta which was ruled by the Khanate of Khiva and has a long history under the name of Khwarezm. The Jaxartes or Syr Darya rises in the Ferghana Valley and flows northwest and then west to meet the northeast corner of the Aral Sea. Between them is the less-famous Zarafshan River which dries up before reaching the Oxus. It waters the great cities of Bokhara and Tamerlane's old capital of Samarkand.

The deserts in the south have enough grass to support a thin nomadic population. The Kyzylkum Desert is between the Oxus and Jaxartes. The Karakum Desert is southwest of the Oxus in Turkmenistan. Between the Aral and Caspian Seas is the thinly-populated Ustyurt Plateau.

When the Russians arrived the organized states were the Khanate of Khiva in the Oxus delta south of the Aral Sea, the Khanate of Bukhara along the Oxus and Zarafshan and the Khanate of Kokand based in the Ferghana Valley. Bokhara had borders with the other two and all three were surrounded by nomads which the Khanates tried to control and tax.

Early contacts

Siberia: Russians first came into contact with central Asia when, in 1582–1639, Cossack adventurers made themselves masters of the Siberian forests. They did not expand south because they were seeking furs, because the Siberian Cossacks were skilled in forest travel and knew little of the steppe and because the forest tribes were few and weak while the steppe nomads were numerous and warlike. See Siberian River Routes and linked articles.

Up the Irtysh River: The Irtysh River rises in what is now China and flows northwest to the Russian base at Tobolsk (founded in 1587). It was thought possible to ascend this river and reach the riches of China and India. In 1654 Fyodor Baykov used this route to reach Peking. The main advance was made under Peter the Great. Some time before 1714[1] Colonel Bukhholts and 1500 men went upriver to a ‘Lake Yamysh’ and returned. In 1715 Bukhholts with 3000 men and 1500 soldiers went to Lake Yamysh again and started to build a fort. Since this was on the fringe of the Dzungar Khanate the Dzungars drove them off. They retreated downriver and founded Omsk. In 1720 Ivan Likharev went upriver and founded Ust-Kamenogorsk. The Dzungars, having just been weakened by the Chinese, left them alone. Several other places were built on the Irtysh at about this time.

The Kazakh steppe: Since the Kazakhs were nomads they could not be conquered in the normal sense. Instead Russian power slowly increased. See History of Kazakhstan.

Around the southern Urals: In 1556 Russia conquered the Astrakhan Khanate on the north shore of the Caspian Sea. The surrounding area was held by the Nogai Horde.To the east of the Nogais were the Kazakhs and to the north, between the Volga and Urals, were the Bashkirs. Around this time some free Cossacks had established themselves on the Ural River. In 1602 they captured Konye-Urgench in Khivan territory. Returning laden with loot they were surrounded by the Khivans and slaughtered. A second expedition lost its way in the snow, starved, and the few survivors were enslaved by the Khivans. There seems to have been a third expedition which is ill-documented.

At the time of Peter the Great there was a major push southeast. In addition to the Irtysh expeditions above there was the disastrous 1717 attempt to conquer Khiva. Following the Russo-Persian War (1722–23) Russia briefly occupied the west side of the Caspian Sea.

About 1734 another move was planned, which provoked the Bashkir War (1735–1740). Once Bashkiria was pacified Russia's southeastern frontier was the Orenburg Line roughly between the Urals and the Caspian Sea.

The area remained quiet for about a hundred years. In 1819 Nikolai Muraviev traveled from the Caspian Sea and contacted the Khan of Khiva.

The Siberian line: By the late eighteenth century Russia held a line of forts roughly along the current Kazakhstan border, which is approximately the boundary between forest and steppe. For reference these forts (and foundation dates) were:

Guryev (1645), Uralsk (1613), Orenburg (1743), Orsk (1735). Troitsk (1743), Petropavlovsk (1753), Omsk (1716), Pavlodar (1720), Semipalitinsk (1718) Ust-Kamenogorsk (1720).

Uralsk was an old settlement of free Cossacks. Orenburg, Orsk and Troitsk were founded as a result of the Bashkir War about 1740 and this section was called the Orenburg Line. Orenburg was long the base from which Russia watched and tried to control the Kazakh steppe. The four eastern forts were along the Irtysh River. After China conquered Xinjiang in 1759 both empires had a few border posts near the current border.

1839: Failed attack on Khiva

In 1839, Russia attempted to conquer Khiva. Vasily Perovsky marched around 5,000 men south from Orenburg. As the winter was unusually cold most of his camels died, forcing him to turn back.

1847–1853: Syr Darya line[2]

(1854)

Southward from the Siberian Line the obvious next step was a line of forts along the Syr Darya eastward from the Aral Sea. This brought Russia into conflict with the Khan of Kokand. In the early 19th century Kokand began expanding northwest from the Ferghana Valley. About 1814 they took Hazrat-i-Turkestan on the Syr Darya and around 1817 they built Ak-Mechet ('White Mosque') further downriver, as well as smaller forts on both sides of Ak-Mechet. The area was ruled by the Beg of Ak Mechet who taxed the local Kazakhs who wintered along the river and had recently driven the Karakalpaks southward. In peacetime Ak-Mechet had a garrison of 50 and Julek 40. The Khan of Khiva had a weak fort on the lower part of the river.

Given Perovsky's failure in 1839 Russia decided on a slow but sure approach. In 1847 Captain Schultz built Raimsk in the Syr delta. It was soon moved upriver to Kazalinsk. Both places were also called Fort Aralsk. Raiders from Khiva and Kokand attacked the local Kazakhs near the fort and were driven off by the Russians. Three sailing ships were built at Orenburg, disassembled, carried across to steppe and rebuilt. They were used to map the lake. In 1852/3 two steamers were carried in pieces from Sweden and launched on the Aral Sea. The local Saxaul proving impractical, they had to be fueled with anthracite brought from the Don. At other times a steamer would tow a barge-load of saxaul and periodically stop to reload fuel. The Syr proved to be shallow, full of sand bars and difficult to navigate during the spring flood.

In 1852 a surveying party went upriver and was turned back before reaching Ak-Mechet. That summer Colonel Blaramberg and about 400 men were sent to raze Ak-Mechet on the pretext that Russia owned the north side of the river. The Kokandis responded by breaking the dykes and flooding the surrounding area. Having brought no scaling ladders or heavy artillery, Blaramberg saw that he could not take the citadel with its 25-foot-high walls. He therefore captured the outworks, burnt everything in the area and retired to Fort Aralsk. The later-famous Yakub Beg had commanded the fort at one time, but it is not clear if he was in command during this first battle. Next summer the Russians assembled a force of over 2000 men, over 2000 each of horses, camels and oxen, 777 wagons, bridging timber, pontoons and the steamer “Perovsky”. To guarantee that there would be enough fodder to move this much from Orenburg to Fort Aralsk, the Kazakhs were forbidden to graze the lands north of the fort. Command was given to the same Perovsky who earlier had failed to reach Khiva. He left Aralsk in June and reached Ak-Mechet on July 2. The Kokandis had strengthened the fort and increased the garrison. A regular siege was begun. When the trenches neared the citadel, a mine was dug under the walls. At 3AM on 9 August 1853 the mine was exploded, creating a large breach. The breach was taken on the third try and by 4:30AM it was all over. 230 Kokandi bodies were counted out of the original 300-man garrison. The place was renamed Fort Perovsky.

During the siege Padurov went 160 km (100 mi) upriver to Julek and found that its defenders had fled. He wrecked the fort as well as he could and returned with its abandoned guns. In September a large force from Kokand reoccupied Julek and advanced toward Fort Perovsky. The column sent to meet them had a hard day's fight, called for reinforcements but next morning found that the Kokandis had retreated. In December a Kokandi force (said to be 12000 men) surrounded Fort Perovsky. A 500-man sortie was soon surrounded and in trouble. Major Shkupa, seeing the enemy camp weakly defended, broke out and burned the camp. Two more sorties drove the Kokandis off in disorder.

Russia now held a 320 km (200 mi) line of forts along the west-flowing part of the Syr Darya. The area between the Aral and Caspian Seas was too thinly-populated to matter. The next question was whether Russia would extend the line east to the mountains (Fort Vernoye was founded in 1854) or continue southeast up the river to Kokand and the Ferghana Valley.

1847–1864: Down the eastern side

In 1847–1864 the Russians crossed the eastern Kazakh steppe and built a line of forts in the irrigated area along the northern Kyrgyz border. In 1864–68 they moved south, conquered Tashkent and Samarkand, confined the Khanate of Kokand to the Ferghana valley and made Bokhara a protectorate. This was the main event of the conquest. Our sources do not say why an eastern approach was chosen, but an obvious guess is that irrigation made it possible to move armies without crossing steppe or desert. This was important when transport required grass-fed horses and camels. We are not told how Russia supplied an army this far east, or if this was a problem. It is not clear why a forward policy was now adopted. It seems that different officials had different opinions and much was decided by local commanders and the luck of the battlefield. All sources report Russian victories over greatly superior forces with kill ratios approaching ten to one. Even if enemy numbers are exaggerated it seems clear that Russian weapons and tactics were now superior to the traditional Asian armies that they faced. All sources mention breachloading rifles without further explanation. Berdan rifles are mentioned without giving numbers. MacGahan, in his account of the Khivan campaign, contrasts explosive artillery to traditional cannonballs. Artillery and rifles could often keep Russian soldiers out of reach of hand weapons.

.jpg.webp)

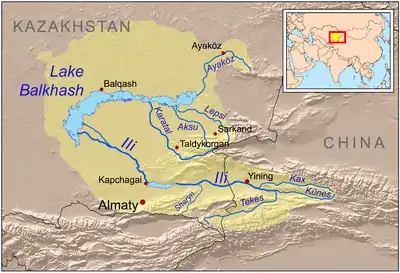

Advance from the northeast (1847–1864): The eastern end of the Kazakh steppe was called Semirechye by the Russians. South of this, along the modern Kyrgyz border, the Tien Shan mountains extend about 640 km (400 mi) to the west. Water coming down from the mountains provides irrigation for a line of towns and supports a natural caravan route. South of this mountain projection is the densely-populated Ferghana Valley ruled by the Khanate of Kokand. South of Ferghana is the Turkestan Range and then the land the ancients called Bactria. West of the northern range is the great city of Tashkent and west of the southern range is Tamerlane's old capital Samarkand.

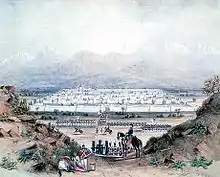

In 1847[3] Kopal was founded southeast of Lake Balkash. In 1852[4] Russia crossed the Ili River and met Kazakh resistance and next year destroyed the Kazakh fort of Tuchubek. In 1854 they founded Fort Vernoye (Almaty) within sight of the mountains. Vernoye is about 800 km (500 mi) south of the Siberian Line. Eight years later, in 1862, Russia took Tokmak (Tokmok) and Pishpek (Bishkek). Russia placed a force at the Kastek pass to block a counterattack from Kokand. The Kokandis used a different pass, attacked an intermediate post, Kolpakovsky rushed from Kastek and completely defeated a much larger army. In 1864 Chernayev[5] took command of the east, led 2500 men from Siberia, and captured Aulie-Ata (Taraz). Russia was now near the west end of the mountain range and about halfway between Vernoye and Ak-Mechet.

In 1851 Russia and China signed the Treaty of Kulja to regulate trade along what was becoming a new border. In 1864 they signed the Treaty of Tarbagatai which approximately established the current Chinese-Kazakh border. The Chinese thereby renounced any claims to the Kazakh steppe, to the extent that they had any.

Up the Syr Darya (1859–1864): Meanwhile, Russia was advancing southeast up the Syr Darya from Ak-Mechet. In 1859, Julek[lower-alpha 1] was taken from Kokand. In 1861 a Russian fort was built at Julek and Yani Kurgan (Zhanakorgan) 80 km (50 mi) upriver was taken. In 1862 Chernyaev reconnoitered the river as far as Hazrat-i-Turkestan and captured the small oasis of Suzak about 105 km (65 mi) east of the river. In June 1864 Veryovkin took Hazrat-i-Turkestan from Kokand. He hastened surrender by bombarding the famous mausoleum. Two Russian columns met in the 240 km (150 mi) gap between Hazrat and Aulie-Ata, thereby completing the Syr-Darya Line.

1864–1868: Kokand and Bukhara subdued

Tashkent (1865): About 80 km (50 mi) south of the new line was Chimkent (Shymkent) which belonged to Kokand. Chernayev easily took it on 3 October 1864. On 15 October he suddenly appeared before Tashkent, failed to take it by sudden assault and retreated to Chimkent. Kokand then tried and failed to re-take Hazrat-i-Turkestan. In April 1865 Chernayev made a second attack on Tashkent. Unable to take such a large place (it was said to have a garrison of 30,000) he occupied the town's water supply at Niazbek. The Kokand Regent Alim Kuli arrived with 6,000 more troops and almost defeated the Russians, but was killed in the fight. The inhabitants now offered to submit to the Emir of Bokhara in return for assistance. About 21 June a party of Bokharans entered the town and more Bokharan troops were on the move. In this critical position Chernayev determined to risk a storm. At 3 a.m. on 27 June, Captain Abramov scaled the wall and opened the Kamelan Gate, advanced along the wall and opened a second gate while another party took the Kokand gate. That day and the next there was constant street fighting, but on the morning of the 29th a deputation of elders offered surrender.

Campaign of 1866: The Bokhara was now involved in the war. In February 1866 Chernayev crossed the Hungry Steppe to the Bokharan fort of Jizzakh. Finding the task impossible, he withdrew to Tashkent followed by Bokharans who were soon joined by Kokandis. At this point Chernayev was recalled for insubordination and replaced by Romanovsky. Romanovsky prepared to attack Bohkara, the Amir moved first, the two forces met on the plain of Irjar.[6] Note: Near Kattakurgan, Uzbekistan about halfway between Jizzakh and Bokhara. The Bukharians scattered, losing most of their artillery, supplies and treasures and more than 1,000 killed, while the Russians lost 12 wounded. Instead of following him, Romanovsky turned east and took Khujand, thus closing the mouth of the Fergana Valley. The losses of the Kokand residents were more than 2.5 thousand killed, 130 Russians killed and wounded. Then he moved west and took Ura-Tepe [lower-alpha 2] and Jizzakh from Bukhara. During the capture of Jizzak, the Bukharians lost 6,000 killed and 3,000 prisoners, as well as all the artillery. In total, during the campaign of 1866, the Russian troops lost 500 people killed and wounded, while the natives lost more than 12,000 killed.[7] Defeats forced Bukhara to start peace talks.

Samarkand (1868): In July 1867 a new Province of Turkestan was created and placed under General von Kaufmann with its headquarters at Tashkent. The Bokharan Amir did not fully control his subjects, there were random raids and rebellions, so Kaufmann decided to hasten matters by attacking Samarkand. After he dispersed a Bokharan force Samarkand closed its gates to the Bokharan army and surrendered (May 1868).[8] He left a garrison in Samarkand and left to deal with some outlying areas.[lower-alpha 3] The garrison was besieged and in great difficulty until Kaufmann returned. On June 2, 1868, in a decisive battle on the Zerabulak heights, the Russians defeated the main forces of the Bukhara Emir, losing less than 100 people, while the Bukhara army lost from 3.5 to 10,000. On 5 July 1868 a peace treaty was signed. The Khanate of Bokhara lost Samarkand and remained a semi-independent vassal until the revolution. The Khanate of Kokand had lost its western territory, was confined to the Ferghana valley and surrounding mountains and remained independent for about 10 years. According to the Bregel's Atlas, if nowhere else, in 1870 the now-vassal Khanate of Bokhara expanded east and annexed that part of Bactria enclosed by the Turkestan Range, the Pamir plateau and the Afghan border.

1875–1876: Liquidation of the Kokand Khanate

In 1875 in the Kokand Khanate he rebelled against Russian rule. Kokand commanders Abdurakhman and Pulat bey seized power in the khanate and began military operations against the Russians. By July 1875 most of the Khan's army and much of his family had deserted to the rebels, so he fled to the Russians at Kojent along with a million British pounds of treasure. Kaufmann invaded the Khanate on September 1, fought several battles and entered the capital on September 10, 1875. In October he transferred command to Mikhail Skobelev. Russian troops under the command of Skobelev and Kaufman defeated the rebels at the Battle of Makhram. In 1876, the Russians freely enter Kokand, the leaders of the rebels were executed, and the khanate was abolished. Fergana Oblast was created in its place.

The Caspian side

Russia now held an approximately triangular area bounded by the eastern mountains and the vassal Khanate of Bokhara along most of the Oxus. The southern point was about 1,600 km (1,000 mi) south of Siberia, 1,600 km (1,000 mi) southeast of Orenburg and 1,900 km (1,200 mi) southeast of the supply bases on the Volga. The next step was to turn this triangle into a rectangle by moving east across the Caspian Sea from the Caucasus. The Caucasus held many troops left over from the Russian conquest of the Caucasus but the Viceroy of the Caucasus had so far not been active in Turkestan. The Caucasus has a fairly dense population but the east side of the Caspian is desert with significant population only in the oases of Khiva and along the Kopet Dag and at Merv in the south. The main events were the defeat of Khiva in 1873, the conquest of the Turkomans in 1881, the annexation of Merv in 1884 and the Panjdeh area in 1885.

For reference, these were the Russian bases on the north and east side of the Caspian:

- Astrakhan (1556–): at the mouth of the Volga River with connections to the rest of Russia

- Guryev (1645–): a small place at the mouth of the Ural River

- Novo-Alexandrovsk (1834–1846): a shallow port that was soon abandoned

- Alexandrovsk (1846–): important at this time but not later

- Kenderli (?1873): a temporary base

- Krasnovodsk (1869–) the best port and later headquarters of the Transcaspian Oblast and start of the Trans-Caspian railway

- Chikishlyar (1871–?): a beach rather than a port

- Ashuradeh (1837–?) a fort and naval station on land claimed by Persia.

1873: The conquest of Khiva

.jpg.webp)

The decision to attack Khiva was made in December 1872. Khiva was an oasis surrounded by several hundred kilometres of desert. The Russians could easily defeat the Khivan army if they could move enough troops across the desert. The place was attacked from five directions. Kaufmann marched west from Tashkent and was joined by another army coming south from Aralsk. They met in the desert, ran short of water, abandoned part of their supplies and reached the Oxus in late May. Veryovkin left from Orenburg, had little difficulty moving along the west side of the Aral Sea and reached the northwest corner of the delta in mid-May. He was joined by Lomakin who had a hard time crossing the desert from the Caspian. Markozov started from Chikishlyar, ran short of water and was forced to turn back. Kaufmann crossed the Oxus, fought a few easy battles and on June 4 the Khan sued for peace. Meanwhile, Veryovkin, who was out of contact with Kaufmann, crossed the delta and attacked the city walls of Khiva until he was called off by Kaufmann. The Khanate of Khiva became a Russian protectorate and remained so until the Russian Revolution.

1879–1885: Turkmenistan: Geok Tepe, Merv and Panjdeh

vodsk

Tepe

River

The Kopet Dagh Mountains run from beyond Geok Tepe northwest toward Krasnovodsk

The Turkoman country remained unconquered. The area corresponded to the Karakum Desert and was inhabited by the Turkoman desert nomads. Irrigation supported a settled population along the Amu-Darya in the northeast and along the north slope of the Kopet Dag mountains in the southwest. East of the Kopet Dag two rivers flowing north from Afghanistan supported the oases of Tejend and Merv. The semi-settled population would drive their flocks out into the desert in spring and fall. The Turkomans had no organized state. Some served as mercenaries for Khiva. They had a habit of raiding Persia and selling the resulting slaves to Khiva. They also had a breed of desert-adapted horse that could usually outrun anything the Cossacks had. Unlike the rather antiquated armies of the Khanates, the Turkomans were good raiders and horsemen, but they could do little against the Russians' modern weapons and explosive artillery. As usual, the main problem was moving men and supplies across the desert.

1879: Lomakin's defeat at Geok Tepe: Lazarev landed a large force at Chikishlyar and began moving men and supplies up the Atrek River. He died suddenly and Lomakin took command. Lomakin crossed the Kopet Dagh with too few men, made an incompetent attack on Geok Tepe and was forced to retreat.

1881: Skobelev's bloody victory at Geok Tepe: Skobelev was put in charge in March 1880. He spent most of the summer and fall moving men and supplies from Chikishlyar to the north side of the Kopet Dagh. In December he marched southwest, besieged Geok Tepe for a month and took it by blowing up a mine under its walls. At least 14000 Tekkes were killed. A week later he occupied Ashkabat 40 km (25 mi) southeast, but could go no further. In May 1881 the occupied area was annexed as the Transcaspian Oblast. The eastern boundary of the Oblast was undefined.

1884: The annexation of Merv: The Trans-Caspian Railway reached Kazyl Arbat at the northwest end of the Kopet Dagh in mid-September 1881. In October through December Lessar surveyed the north side of the Kopet Dagh and reported that there would be no problem building a railway along it. From April 1882 he examined the country almost to Herat and reported that were no military obstacles between the Kopet Dagh and Afghanistan. Nazirov or Nazir Beg went to Merv in disguise and then crossed the desert to Bokhara and Tashkent.

The irrigated area along the Kopet Dagh ends east of Ashkebat. Further east there is desert, then the small oasis of Tejent, more desert and the much larger oasis of Merv. Merv had the great fortress of Kaushut Khan and was inhabited by the same Tekkes that fought at Geok Tepe. As soon as the Russians were established in Ashkabad traders, and also spies, began moving between the Kopet Dagh and Merv. Some elders from Merv went north to Petroalexandrovsk and offered a degree of submission to the Russians there. The Russians at Ashkebat had to explain that both groups were part of the same empire. In February 1882 Alikhanov visited Merv and began talking to Makhdum Kuli Khan who had been in command at Geok Tepe. In September he persuaded him to take an oath of allegiance to the White Czar.

Skobelev had been replaced by Rohrberg in the spring of 1881, who was followed General Komarov in the spring of 1883. Near the end of 1883, General Komarov led 1500 men to occupy the Tejend oasis. After Komarov's occupation of Tejend Alikhanov and Makhdum Kuli Khan went to Merv and called a meeting of elders, one threatening and the other persuading. Having no wish to repeat the slaughter at Geok Tepe, 28 elders went to Ashkabad and on February 12 took an oath of allegiance in the presence of General Komarov. A faction in Merv tried to resist but was too weak to accomplish anything. On March 16, 1884 Komarov occupied Merv. The subject Khanates of Khiva and Bokhara were now surrounded by Russian territory.

1885: Expansion stopped at Panjdeh: Between Merv and the current Afghan border is about 230 km (140 mi) of semi-desert. South of that is the important border fort of Herat. In the summer of 1884 Britain and Russia agreed to formalize the northwest Afghan border. The Russians did what they could to push the border south before it became frozen. When they captured the Afghan fort of Panjdeh Britain came close to threatening war. Both sides backed down and the border was delineated between 1885 and 1886.

1872–1895: The Eastern Mountains

The natural eastern boundary of Russian Turkestan was the eastern mountains, but the exact line had to be settled. There were four main problems.

1867–1877: Yakub Beg: East of the Feghana Valley and southeast of Fort Vernoye on the other side of the mountains is the oval Tarim Basin which had belonged to China since 1759. During the Dungan Revolt (1862–77) China lost partial control of its western territories. A man named Yakub Beg made himself master of Kashgar and most of the Tarim Basin. Kaufmann twice thought of attacking him. In 1872 forces were massed on the border but this was called off because of the impending war against Khiva. In 1875 more serious plans were made. A mission was sent to the Khan of Kokand to ask permission to move forces through his domains. A revolt broke out and the Russian troops were used instead to annex Kokand (see below). In 1877 China re-conquered the Tarim Basin and Yakub Beg was killed.

1871–1883: temporary occupation of Kulja: The Tien Shan mountains run along the northern border of Kyrgyzstan. They continue east and separate Dzungaria in the north from the Tarim Basin in the south. On the Chinese side the Borohoro Mountains branch off creating the upper Ili River valley with its capital of Kulja (modern Yining City). Although normally part of Dzungaria the valley opens out onto the Russian-controlled steppe. In 1866 the Dungans captured Kulja and massacred its inhabitants. They soon began fighting with the Taranchis (Uigurs) who soon became dominant. In 1870 it appeared that Yakub Beg might move on Kulja so Kaufmann occupied the Muzart Pass. In June 1871 General Kolpakovsky crossed the border and occupied Kulja (4 July 1871). Some talked of permanent occupation but the Russian Foreign Office told the Chinese that the province would be returned as soon as the Emperor could send enough troops to maintain order. In 1877 China regained control of Chinese Turkestan and requested the return of Kulja. In September 1879 the Chinese ambassador concluded a treaty at Livadia but his government rejected it. This was replaced by the more favorable Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881). Russia finally evacuated Kulja in the spring of 1883. There were the usual border disputes and an additional protocol was signed at Chuguchak (Tacheng?) on October 19, 1883. The re-occupation of Kulja was one of the few Chinese successes against a Western power during the nineteenth century.

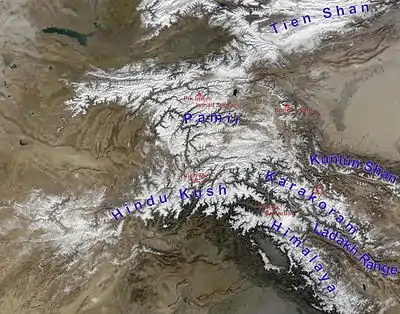

Right: Tarim Basin

Left: part of Afghanistan, Hindu Kush, Bactria, Turkestan Range, Ferghana Valley, main range of the Tien Shan

1893: Pamirs occupied: [9] The southeast corner of Russian Turkestan was the high Pamirs which is now the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region of Tajikistan. The high plateaus on the east are used for summer pasture. On the west side difficult gorges run down to the Panj river and Bactria. In 1871 Alexei Pavlovich Fedchenko got the Khan's permission to explore southward. He reached the Alay Valley but his escort would not permit him to go south onto the Pamir plateau. In 1876 Skobelev chased a rebel south to the Alay Valley and Kostenko went over the Kyzylart Pass and mapped the area around Karakul Lake on the northeast part of the plateau. In the next 20 years most of the area was mapped. In 1891 the Russians informed Francis Younghusband that he was on their territory and later escorted a Lieutenant Davidson out of the area ('Pamir Incident'). In 1892 a battalion of Russians under Mikhail Ionov entered the area and camped near the present Murghab, Tajikistan in the northeast. Next year they built a proper fort there (Pamirskiy Post). In 1895 their base was moved west to Khorog facing the Afghans. In 1893 the Durand Line established the Wakhan Corridor between the Russian Pamirs and British India.

The Great Game

The Great Game[10] refers to British attempts to block Russian expansion southeast toward India. Although there was much talk of a possible Russian invasion of India and a number of British agents and adventurers penetrated central Asia, the British did nothing serious to prevent the Russian conquest of Turkestan, with one exception. Whenever Russian agents approached Afghanistan they reacted very strongly, seeing Afghanistan as a necessary buffer state for the defense of India.

A Russian invasion of India seems improbable, but a number of British writers considered how it might be done. When little was known about the geography it was thought that they could reach Khiva and sail up the Oxus to Afghanistan. More realistically they might gain Persian support and cross northern Persia. Once in Afghanistan they would swell their armies with offers of loot and invade India. Alternatively, they might invade India and provoke a native rebellion. The goal would probably not be the conquest of India but to put pressure on the British while Russia did something more important such as taking Constantinople.

In 1801 there was some loose talk of a joint Franco-Russian invasion of India. During the Russo-Persian War (1804–13) both British and French agents were active in Persia, their goals varying depending on which power was allied with Russia at the time. In 1810 Charles Christie and Henry Pottinger crossed western Afghanistan and eastern Persia. Christie was killed in 1812 supporting the Persians at the Battle of Aslanduz. In 1819 Muraviev reached Khiva. A Russian mission reached Bokhara in 1820. In 1825 Moorcroft reached Bukhara. In 1830 Arthur Conolly tried to reach Khiva from Persia but was turned back by bandits and continued on to Herat and British India. In 1832 Alexander Burnes reached Bokhara.

The period from 1837 to 1842 was especially active. In 1839, at the time of Perovsky's failed attack on Khiva, Abbot went to Khiva to negotiate the release of Russian slaves held there in order to remove a pretext for the invasion. He failed. Next year Richmond Shakespear went after him, was successful, and led 416 Russian slaves to the Caspian. In 1837 Jan Prosper Witkiewicz reached Kabul. In 1838 Persia besieged Herat, with British and Russian agents supporting the two sides. Britain ended the siege by occupying a Persian island. In 1838 Charles Stoddart went to Bokhara and was arrested. In 1841 Arthur Conolly went to secure his release and both were executed in 1842. During the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–42) Britain invaded Afghanistan, was driven out, re-invaded and withdrew.

The British took Sindh in 1843 and Punjab in 1849, thereby gaining the Indus River and a border with Afghanistan. The Crimean War occurred in 1853–56. A second Persian attack on Herat led to the Anglo-Persian War of 1856–57. The Indian Mutiny occurred in 1857–58. This was about the time Russian was building forts east from the Aral Sea (1847–53). The Russian capture of Tashkent (1865) and Samarkand(1868) produced no British response.

In 1875, following the conquest of Khiva, Frederick Gustavus Burnaby rode from Orenburg to Khiva, an event that was only important because of his widely-read book. Kaufman's intrigues in Kabul provoked the Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878–80. During the second battle of Geok Tepe Colonel Charles Stewart was on the south side of the mountain doing something that has never been clarified.

On the Chinese side of the mountains a line of passes corresponding the Karakoram Highway provided a trade and pilgrim route from the Tarim Basin to India. It was not clear whether this could be used by an army. At the time of Yakub Beg both Russian and British agents were active at his court. A number of Indians in the British service mapped the area around the Pamirs. Russian expansion in the Pamirs provoked the British to move northward and gain control of places like Hunza and Chitral.

The Great Game came to an end with the demarcation of the northern Afghan border in 1886 and 1893 and the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907.

Notes

- The location is uncertain, possibly the modern Zhilek.

- Apparently Istaravshan about 32 km (20 mi) south of the middle 160 km (100 mi) the line between Jizzakh and Kozhent.

- Shahrisabz, Katti-Kurgan, Hussein Bek of Urgut, Omar Bek of Chilek, Jura Bek, Baba Bek and others.

Citations

- Mancall. Note: The dates for the first Bukhholts expedition on pages 211–212 are unfortunately self-contradictory.

- Valikhanov, Chapters viii-x.

- Bregel.

- "An Indian Officer". Note: The author puts this as two years before the foundation of Vernoye which he misdates to 1855, so 1852 is probably correct.

- MacKenzie.

- Bregel, p. 64.

- Kersnovsky, A. A. History of the Russian army Т. 2. — М.: Голос, 1993.—336 с., ил. — ISBN 5-7117-0058-8, 5-7117-0059-6. — 100 000 экз.

- Malikov, pp. 180-198.

- Middleton.

- Hopkirk.

References and further reading

- Bregel, Yuri. An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, 2003.

- Brower, Daniel. Turkestan and the Fate of the Russian Empire (London) 2003

- Curzon, G.N. Russia in Central Asia (London) 1889 online free

- Ewans, Martin. Securing the Indian frontier in Central Asia: Confrontation and negotiation, 1865-1895 (Routledge, 2010).

- Hopkirk, Peter. The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia, John Murray, 1990.

- An Indian Officer (1894). "Russia's March Towards India: Volume 1". Google Books. Sampson Low, Marston & Company. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Johnson, Robert. Spying for empire: the great game in Central and South Asia, 1757-1947 (Greenhill Books/Lionel Leventhal, 2006).

- Malikov, A.M. The Russian conquest of the Bukharan emirate: military and diplomatic aspects in Central Asian Survey, volume 33, issue 2, 2014.

- Mancall, Mark. Russia and China: Their Diplomatic Relations to 1728, Harvard University press, 1971.

- McKenzie, David. The Lion of Tashkent: The Career of General M. G. Cherniaev, University of Georgia Press, 1974.

- Middleton, Robert and Huw Thomas. Tajikistan and the High Pamirs, Odyssey Books, 2008.

- Morris, Peter. "The Russians in Central Asia, 1870-1887." Slavonic and East European Review 53.133 (1975): 521-538 online.

- Morrison, Alexander. "Introduction: Killing the Cotton Canard and getting rid of the Great Game: rewriting the Russian conquest of Central Asia, 1814–1895." (2014): 131-142. online

- Morrison, Alexander. Russian rule in Samarkand 1868-1910: A comparison with British India (Oxford UP, 2008).

- Peyrouse, Sébastien. "Nationhood and the minority question in Central Asia. The Russians in Kazakhstan." Europe-Asia Studies 59.3 (2007): 481-501.

- Pierce, Richard A. Russian Central Asia, 1867-1917: a study in colonial rule (1960) online free to borrow

- Quested, Rosemary. The expansion of Russia in East Asia, 1857-1860 (University of Malaya Press, 1968).

- Saray, Mehmet. "The Russian conquest of central Asia." Central Asian Survey 1.2-3 (1982): 1-30.

- Schuyler, Eugene. Turkistan (London) 1876 2 Vols. online free

- Skrine, Francis Henry, The Heart of Asia, circa 1900.

- Spring, Derek W. "Russian imperialism in Asia in 1914." Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique (1979): 305-322 online

- Sunderland, Willard. "The Ministry of Asiatic Russia: the colonial office that never was but might have been." Slavic Review (2010): 120-150 online.

- Valikhanov, Chokan Chingisovich, Mikhail Ivanovich Venyukov, and Other Travelers. The Russians in Central Asia: Their Occupation of the Kirghiz Steppe and the line of the Syr-Daria: Their Political Relations with Khiva, Bokhara, and Kokan: Also Descriptions of Chinese Turkestan and Dzungaria, Edward Stanford, 1865.

- Wheeler, Geoffrey. The Russians in Central Asia History Today. March 1956, 6#3 pp 172–180.

- Wheeler, Geoffrey. The modern history of Soviet Central Asia (1964). online free to borrow

- Williams, Beryl. "Approach to the Second Afghan War: Central Asia during the Great Eastern Crisis, 1875–1878." 'International History Review 2.2 (1980): 216-238.

- Yapp, M. E. Strategies of British India. Britain, Iran and Afghanistan, 1798-1850 (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1980)